Устойчивое развитие — это социальная цель, позволяющая людям сосуществовать на Земле в течение длительного времени. Определения этого термина являются спорными и различаются в зависимости от литературы, контекста и времени. [2] [1] Устойчивое развитие обычно имеет три измерения (или столпа): экологическое, экономическое и социальное. [1] Многие определения подчеркивают экологический аспект. [3] [4] Это может включать решение ключевых экологических проблем , включая изменение климата и утрату биоразнообразия . Идея устойчивости может определять решения на глобальном, национальном и индивидуальном уровнях. [5] Родственной концепцией является концепция устойчивого развития , и эти термины часто используются для обозначения одного и того же. [6] ЮНЕСКО различает эти две вещи следующим образом: « Устойчивое развитие часто рассматривается как долгосрочная цель (т.е. более устойчивый мир), в то время как устойчивое развитие подразумевает множество процессов и путей ее достижения». [7]

Детали, касающиеся экономического аспекта устойчивости, противоречивы. [1] Ученые обсуждали это в рамках концепции слабой и сильной устойчивости . Например, всегда будет противоречие между идеями «благосостояния и процветания для всех» и охраной окружающей среды , [8] [1] , поэтому необходимы компромиссы . Было бы желательно найти способы отделить экономический рост от нанесения вреда окружающей среде . [9] Это означает использование меньшего количества ресурсов на единицу продукции даже при росте экономики. [10] Это снижает воздействие экономического роста на окружающую среду, например загрязнение окружающей среды . Сделать это сложно. [11] [12] Некоторые эксперты говорят, что нет никаких доказательств того, что это происходит в необходимом масштабе. [13]

Измерить устойчивость в метрической шкале сложно . [14] Показатели учитывают окружающую среду, общество и экономику. Однако четкого определения показателей устойчивости не существует . [15] Показатели развиваются и включают индикаторы , контрольные показатели и аудиты. Они включают стандарты устойчивого развития и системы сертификации, такие как Fairtrade и Organic . Они также включают в себя индексы и системы бухгалтерского учета, такие как корпоративная отчетность об устойчивом развитии и учет тройной прибыли .

Для достижения перехода к устойчивому развитию необходимо устранить множество препятствий на пути к устойчивому развитию . [5] : 34 [16] Некоторые препятствия возникают из-за природы и ее сложности. Другие барьеры не связаны с концепцией устойчивости. Например, они могут быть результатом доминирующих институциональных рамок в странах.

Глобальные проблемы устойчивого развития трудно решить, поскольку они требуют глобальных решений. Существующие глобальные организации, такие как ООН и ВТО, неэффективны в обеспечении соблюдения действующих глобальных правил. Одной из причин этого является отсутствие подходящих механизмов санкций . [5] : 135–145 Правительства – не единственные источники действий по обеспечению устойчивости. Например, бизнес-группы пытались интегрировать экологические проблемы в экономическую деятельность. [17] [18] Религиозные лидеры подчеркнули необходимость заботы о природе и экологической стабильности. Отдельные люди также могут жить более устойчивым образом . [5]

Люди критиковали идею устойчивости. Одним из моментов критики является то, что эта концепция расплывчата и является всего лишь модным словечком . [1] Другая причина заключается в том, что устойчивое развитие может оказаться недостижимой целью. [19] Некоторые эксперты отмечают, что «ни одна страна не обеспечивает то, что нужно ее гражданам, не нарушая биофизических планетарных границ». [20] : 11

Устойчивое развитие рассматривается как « нормативная концепция ». [5] [21] [22] [2] Это означает, что оно основано на том, что люди ценят или считают желательным: «Поиск устойчивости предполагает соединение того, что известно в результате научных исследований, с приложениями в поисках того, чего люди хотят в будущем. " [22]

Комиссия ООН по окружающей среде и развитию 1983 года ( Комиссия Брундтланд ) оказала большое влияние на использование термина « устойчивое развитие» сегодня. В докладе Брундтланд комиссии за 1987 год было дано определение устойчивого развития . В докладе « Наше общее будущее » оно определяется как развитие, которое «удовлетворяет потребности настоящего, не ставя под угрозу способность будущих поколений удовлетворять свои собственные потребности». [23] [24] Отчет помог сделать устойчивое развитие основным направлением политических дискуссий. Он также популяризировал концепцию устойчивого развития . [1]

Некоторые другие ключевые концепции, иллюстрирующие значение устойчивости, включают: [22]

В повседневном использовании устойчивое развитие часто фокусируется на экологическом аспекте. [ нужна цитата ]

Ученые говорят, что единое конкретное определение устойчивости никогда не будет возможным. Но эта концепция по-прежнему полезна. [2] [22] Были попытки дать этому определение, например:

Некоторые определения сосредоточены на экологическом измерении. Оксфордский словарь английского языка определяет устойчивость как: «свойство быть экологически устойчивым; степень, в которой процесс или предприятие можно поддерживать или продолжать, избегая при этом долгосрочного истощения природных ресурсов». [26]

Термин «устойчивость» происходит от латинского слова «sustinere» . «Поддерживать» может означать поддерживать, поддерживать, поддерживать или терпеть. [27] [28] Таким образом, устойчивость — это способность продолжаться в течение длительного периода времени.

В прошлом устойчивость относилась к экологической устойчивости. Это означало использование природных ресурсов , чтобы люди в будущем могли продолжать полагаться на них в долгосрочной перспективе. [29] [30] Концепция устойчивости, или Nachhaltigkeit по-немецки, восходит к Гансу Карлу фон Карловицу (1645–1714) и применяется к лесному хозяйству . Теперь это будет называться устойчивым лесопользованием . [31] Он использовал этот термин для обозначения долгосрочного ответственного использования природных ресурсов. В своей работе 1713 года «Silvicultura o Economica» [32] он писал, что «высшее искусство/наука/трудолюбие [...] будет состоять в таком сохранении и пересадке древесины, чтобы обеспечить непрерывное, постоянное и устойчивое использование». [33] Сдвиг в использовании термина «устойчивость» от сохранения лесов (для будущего производства древесины) к более широкому сохранению ресурсов окружающей среды (для поддержания мира для будущих поколений) восходит к книге Эрнста Баслера 1972 года, основанной на серии лекции в Массачусетском технологическом институте [34]

Сама идея возникла очень давно: сообщества всегда беспокоились о способности окружающей среды поддерживать их в долгосрочной перспективе. Многие древние культуры, традиционные общества и коренные народы ограничивали использование природных ресурсов. [35]

Термины устойчивость и устойчивое развитие тесно связаны. На самом деле, они часто используются для обозначения одного и того же. [6] Оба термина связаны с концепцией «трех измерений устойчивости». [1] Одно из различий заключается в том, что устойчивость – это общая концепция, тогда как устойчивое развитие может быть политикой или организационным принципом. Ученые говорят, что устойчивость — это более широкое понятие, поскольку устойчивое развитие фокусируется главным образом на благополучии людей. [22]

Устойчивое развитие преследует две взаимосвязанные цели. Оно направлено на достижение целей человеческого развития . Он также направлен на то, чтобы природные системы могли предоставлять природные ресурсы и экосистемные услуги, необходимые для экономики и общества. Концепция устойчивого развития сосредоточилась на экономическом развитии , социальном развитии и защите окружающей среды для будущих поколений. [ нужна цитата ]

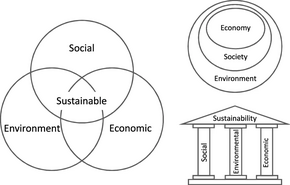

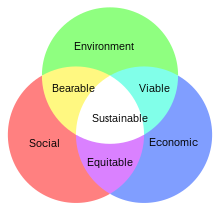

Ученые обычно выделяют три различные области устойчивости. Это экологические, социальные и экономические. Для этого понятия используется несколько терминов. Авторы могут говорить о трех столпах, измерениях, компонентах, аспектах, [36] перспективах, факторах или целях. В данном контексте все это означает одно и то же. [1] Трехмерная парадигма имеет мало теоретических оснований. Оно возникло без единой точки происхождения. [1] [37] Ученые редко подвергают сомнению само различие. Идея трехмерной устойчивости является доминирующей интерпретацией в литературе. [1]

В докладе Брундтланд окружающая среда и развитие неразделимы и идут рука об руку в поисках устойчивости. В нем устойчивое развитие описывается как глобальная концепция, связывающая экологические и социальные проблемы. Он добавил, что устойчивое развитие важно как для развивающихся , так и для промышленно развитых стран :

«Окружающая среда» — это то, где мы все живем; а «развитие» — это то, что мы все делаем, пытаясь улучшить свою судьбу в этом жилище. Эти двое неразделимы. [...] Мы пришли к пониманию того, что необходим новый путь развития, который поддерживал бы прогресс человечества не только по частям в течение нескольких лет, но и для всей планеты в отдаленном будущем. Таким образом, «устойчивое развитие» становится целью не только «развивающихся» стран, но и индустриальных.

- Наше общее будущее (также известное как Доклад Брундтланд), [23] : Предисловие и раздел I.1.10.

Декларация Рио-де -Жанейро 1992 года рассматривается как «основополагающий инструмент на пути к устойчивому развитию». [38] : 29 Он включает конкретные ссылки на целостность экосистемы. [38] : 31 План, связанный с выполнением Рио-де-Жанейрской декларации, также рассматривает устойчивость таким же образом. В плане « Повестка дня на 21 век » говорится об экономических, социальных и экологических аспектах: [39] : 8,6.

Страны могли бы разработать системы мониторинга и оценки прогресса на пути к достижению устойчивого развития, приняв показатели, которые измеряют изменения в экономических, социальных и экологических измерениях.

Повестка дня на период до 2030 года от 2015 года также рассматривала устойчивость таким же образом. Он рассматривает 17 целей устойчивого развития (ЦУР) со 169 задачами как балансирующие «три измерения устойчивого развития: экономическое, социальное и экологическое». [40]

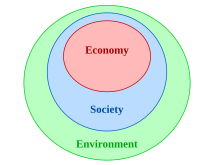

Ученые обсудили, как ранжировать три измерения устойчивости. Во многих публикациях утверждается, что экологический аспект является наиболее важным. [3] [4] ( Планетарная целостность или экологическая целостность — это другие термины, обозначающие экологический аспект.)

По мнению многих экспертов, защита экологической целостности является основой устойчивого развития. [4] Если это так, то экологический аспект ограничивает экономическое и социальное развитие. [4]

Диаграмма с тремя вложенными эллипсами – это один из способов показать три измерения устойчивости вместе с иерархией: это придает экологическому измерению особый статус. На этой диаграмме окружающая среда включает общество, а общество включает экономические условия. Таким образом, он подчеркивает иерархию.

Другая модель показывает три измерения аналогичным образом: в этой модели свадебного торта ЦУР экономика представляет собой меньшую часть социальной системы. А общественная система, в свою очередь, представляет собой меньшую часть биосферной системы. [42]

В 2022 году в ходе оценки были изучены политические последствия Целей устойчивого развития. Оценка показала, что «целостность систем жизнеобеспечения Земли» имеет важное значение для устойчивости. [3] : 140 Авторы заявили, что «ЦУР не признают, что планетарные проблемы, проблемы людей и процветания являются частью одной земной системы, и что защита планетарной целостности должна быть не средством достижения цели, а целью сам". [3] : 147 Аспект защиты окружающей среды не является явным приоритетом для ЦУР. Это вызывает проблемы, поскольку может побудить страны уделять меньше внимания окружающей среде в своих планах развития. [3] : 144 Авторы заявляют, что «устойчивость в планетарном масштабе достижима только в рамках всеобъемлющей Цели Планетарной Целостности, которая признает биофизические пределы планеты». [3] : 161

Другие концепции полностью игнорируют разделение устойчивости на отдельные измерения. [1]

Экологический аспект занимает центральное место в общей концепции устойчивого развития. В 1960-х и 1970-х годах люди все больше и больше осознавали проблему загрязнения окружающей среды. Это привело к дискуссиям по вопросам устойчивости и устойчивого развития. Этот процесс начался в 1970-х годах с заботы об окружающей среде. К ним относятся природные экосистемы или природные ресурсы и человеческая среда. Позже оно распространилось на все системы, поддерживающие жизнь на Земле, включая человеческое общество. [43] : 31 Уменьшение этого негативного воздействия на окружающую среду повысит экологическую устойчивость. [43] [44]

Загрязнение окружающей среды – явление не новое. Но на протяжении большей части человеческой истории это было лишь местной или региональной проблемой. Осведомленность о глобальных экологических проблемах возросла в 20 веке. [43] : 5 [45] Вредное воздействие и глобальное распространение пестицидов, таких как ДДТ, стали объектом пристального внимания в 1960-х годах. [46] В 1970-х годах выяснилось, что хлорфторуглероды (ХФУ) разрушают озоновый слой . Это привело к фактическому запрету ХФУ Монреальским протоколом в 1987 году. [5] : 146

В начале 20 века Аррениус обсуждал влияние парниковых газов на климат (см. также: История науки об изменении климата ). [47] Изменение климата в результате деятельности человека стало академической и политической темой несколько десятилетий спустя. Это привело к созданию МГЭИК в 1988 году и РКИК ООН в 1992 году.

В 1972 году состоялась Конференция ООН по окружающей среде человека . Это была первая конференция ООН по экологическим проблемам. Он заявил, что важно защищать и улучшать среду обитания человека. [48] : 3 Он подчеркнул необходимость защиты дикой природы и естественной среды обитания: [48] : 4

Природные ресурсы Земли, включая воздух, воду, землю, флору и фауну, а также природные экосистемы, должны охраняться на благо нынешнего и будущих поколений посредством тщательного планирования или управления, в зависимости от обстоятельств.

— Конференция ООН по окружающей среде человека , [48] : стр. 4., Принцип 2.

В 2000 году ООН провозгласила восемь целей развития тысячелетия . Цель заключалась в том, чтобы мировое сообщество достигло их к 2015 году. Цель 7 заключалась в «обеспечении экологической устойчивости». Но в этой цели не упоминались концепции социальной или экономической устойчивости. [1]

Конкретные проблемы часто доминируют в общественных дискуссиях об экологическом аспекте устойчивого развития: в 21 веке к этим проблемам относятся изменение климата , биоразнообразие и загрязнение окружающей среды. Другими глобальными проблемами являются потеря экосистемных услуг , деградация земель , воздействие животноводства на окружающую среду , а также загрязнение воздуха и воды , включая загрязнение морской среды пластиком и закисление океана . [49] [50] Многие люди беспокоятся о воздействии человека на окружающую среду . К ним относятся воздействия на атмосферу, землю и водные ресурсы . [43] : 21

Деятельность человека в настоящее время оказывает влияние на геологию и экосистемы Земли . Это побудило Пола Крутцена назвать нынешнюю геологическую эпоху антропоценом . [51]

Экономический аспект устойчивости является спорным. [1] Это связано с тем, что термин « развитие» в рамках устойчивого развития можно интерпретировать по-разному. Некоторые могут подумать, что это означает только экономическое развитие и рост . Это может способствовать созданию экономической системы, которая вредна для окружающей среды. [52] [53] [54] Другие больше внимания уделяют компромиссу между сохранением окружающей среды и достижением целей благосостояния для удовлетворения основных потребностей (еда, вода, здоровье и жилье). [8]

Экономическое развитие действительно может уменьшить голод или энергетическую бедность . Особенно это касается наименее развитых стран . Вот почему Цель устойчивого развития 8 призывает к экономическому росту как движущей силе социального прогресса и благосостояния. Его первая цель заключается в следующем: «рост ВВП в наименее развитых странах должен составлять не менее 7 процентов в год». [55] Однако задача состоит в том, чтобы расширить экономическую деятельность, одновременно снижая ее воздействие на окружающую среду. [10] : 8 Другими словами, человечеству придется найти способы достижения социального прогресса (потенциально за счет экономического развития) без чрезмерной нагрузки на окружающую среду.

В докладе Брундтланд говорится, что бедность вызывает экологические проблемы. Бедность также является результатом них. Таким образом, решение экологических проблем требует понимания факторов, лежащих в основе мировой бедности и неравенства. [23] : Раздел I.1.8 Отчет требует нового пути развития для устойчивого прогресса человечества. В нем подчеркивается, что это цель как развивающихся, так и промышленно развитых стран. [23] : Раздел I.1.10.

ЮНЕП и ПРООН запустили Инициативу по борьбе с бедностью и окружающей средой в 2005 году, которая преследует три цели. Они сокращают крайнюю бедность, выбросы парниковых газов и чистую потерю природных активов. Это руководство по структурным реформам позволит странам достичь ЦУР. [56] [57] : 11 Он также должен показать, как найти компромисс между экологическим следом и экономическим развитием. [5] : 82

Социальный аспект устойчивости четко не определен. [58] [59] [60] Одно определение гласит, что общество является устойчивым в социальном плане, если люди не сталкиваются со структурными препятствиями в ключевых областях. Этими ключевыми областями являются здоровье, влияние, компетентность, беспристрастность и осмысленность . [61]

Некоторые ученые ставят социальные вопросы в самый центр дискуссий. [62] Они предполагают, что все сферы устойчивого развития являются социальными. К ним относятся экологическая, экономическая, политическая и культурная устойчивость. Все эти области зависят от отношений между социальным и природным. Экологическая область определяется как включенность человека в окружающую среду. С этой точки зрения социальная устойчивость охватывает всю человеческую деятельность. [63] Это выходит за рамки пересечения экономики, окружающей среды и социального обеспечения. [64]

Существует множество широких стратегий создания более устойчивых социальных систем. Они включают улучшение образования и расширение политических прав и возможностей женщин . Особенно это касается развивающихся стран. Они включают в себя большее уважение к социальной справедливости . Это предполагает равенство между богатыми и бедными как внутри стран, так и между ними. И это включает в себя равенство между поколениями . [65] Предоставление большего количества сетей социальной защиты уязвимым группам населения будет способствовать социальной устойчивости. [66] : 11

Общество с высокой степенью социальной устойчивости приведет к созданию пригодных для жизни сообществ с хорошим качеством жизни (справедливым, разнообразным, взаимосвязанным и демократическим). [67]

Сообщества коренных народов могут уделять особое внимание конкретным аспектам устойчивости, например, духовным аспектам, управлению на уровне общины и акценту на месте и местности. [68]

Некоторые эксперты предложили дополнительные измерения. Они могут охватывать институциональные, культурные, политические и технические аспекты. [1]

Некоторые ученые выступают за четвертое измерение. Они говорят, что традиционные три измерения не отражают сложность современного общества. [69] Например, Повестка дня на XXI век в области культуры и организация «Объединенные города и местные органы власти» утверждают, что устойчивое развитие должно включать в себя прочную культурную политику . Они также выступают за культурный аспект во всей государственной политике. Другим примером был подход «Круги устойчивого развития» , который включал культурную устойчивость . [70]

Люди часто спорят о взаимосвязи между экологическими и экономическими аспектами устойчивости. [71] В научных кругах это обсуждается под терминами «слабая» и «сильная устойчивость» . В этой модели концепция слабой устойчивости утверждает, что капитал, созданный людьми, может заменить большую часть природного капитала . [72] [71] Природный капитал – это способ описания ресурсов окружающей среды. Люди могут называть это природой. Примером этого является использование экологических технологий для снижения загрязнения. [73]

Противоположной концепцией в этой модели является сильная устойчивость . Это предполагает, что природа предоставляет функции, которые технология не может заменить. [74] Таким образом, высокая устойчивость признает необходимость сохранения экологической целостности. [5] : 19 Утрата этих функций делает невозможным восстановление или восстановление многих ресурсов и экосистемных услуг. Примерами могут служить биоразнообразие, а также опыление и плодородные почвы . Другие – это чистый воздух, чистая вода и регулирование климатических систем .

Слабая устойчивость подверглась критике. Он может быть популярен среди правительств и бизнеса, но не обеспечивает сохранение экологической целостности Земли. [75] Вот почему экологический аспект так важен. [4]

Всемирный экономический форум проиллюстрировал это в 2020 году. Он обнаружил, что создание экономической стоимости на сумму 44 триллиона долларов зависит от природы. Таким образом, эта стоимость, составляющая более половины мирового ВВП, уязвима к утрате природы. [76] : 8 Три крупных сектора экономики сильно зависят от природы: строительство , сельское хозяйство , а также продукты питания и напитки . Утрата природы является результатом многих факторов. К ним относятся изменение землепользования , изменение использования моря и изменение климата. Другими примерами являются использование природных ресурсов, загрязнение окружающей среды и инвазивные чужеродные виды . [76] : 11

Компромиссы между различными аспектами устойчивости являются общей темой для дискуссий. Сбалансировать экологические, социальные и экономические аспекты устойчивости сложно. Это связано с тем, что часто возникают разногласия относительно относительной важности каждого из них. Чтобы решить эту проблему, необходимо интегрировать, сбалансировать и согласовать измерения. [1] Например, люди могут сделать выбор: сделать экологическую целостность приоритетом или поставить ее под угрозу. [4]

Some even argue the Sustainable Development Goals are unrealistic. Their aim of universal human well-being conflicts with the physical limits of Earth and its ecosystems.[20]: 41

There are several methods to measure or describe human impacts on Earth. They include the ecological footprint, ecological debt, carrying capacity, and sustainable yield. The idea of planetary boundaries is that there are limits to the carrying capacity of the Earth. It is important not to cross these thresholds to prevent irreversible harm to the Earth.[14][84] These planetary boundaries involve several environmental issues. These include climate change and biodiversity loss. They also include types of pollution. These are biogeochemical (nitrogen and phosphorus), ocean acidification, land use, freshwater, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosols, and chemical pollution.[14][85] (Since 2015 some experts refer to biodiversity loss as change in biosphere integrity. They refer to chemical pollution as introduction of novel entities.)

The IPAT formula measures the environmental impact of humans. It emerged in the 1970s. It states this impact is proportional to human population, affluence and technology.[86] This implies various ways to increase environmental sustainability. One would be human population control. Another would be to reduce consumption and affluence[87] such as energy consumption. Another would be to develop innovative or green technologies such as renewable energy. In other words, there are two broad aims. The first would be to have fewer consumers. The second would be to have less environmental footprint per consumer.

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment from 2005 measured 24 ecosystem services. It concluded that only four have improved over the last 50 years. It found 15 are in serious decline and five are in a precarious condition.[88]: 6–19

Experts in environmental economics have calculated the cost of using public natural resources. One project calculated the damage to ecosystems and biodiversity loss. This was the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity project from 2007 to 2011.[89]

An entity that creates environmental and social costs often does not pay for them. The market price also does not reflect those costs. In the end, government policy is usually required to resolve this problem.[90]

Decision-making can take future costs and benefits into account. The tool for this is the social discount rate. The bigger the concern for future generations, the lower the social discount rate should be.[91] Another approach is to put an economic value on ecosystem services. This allows us to assess environmental damage against perceived short-term welfare benefits. One calculation is that, "for every dollar spent on ecosystem restoration, between three and 75 dollars of economic benefits from ecosystem goods and services can be expected".[92]

In recent years, economist Kate Raworth has developed the concept of doughnut economics. This aims to integrate social and environmental sustainability into economic thinking. The social dimension acts as a minimum standard to which a society should aspire. The carrying capacity of the planet acts an outer limit.[93]

There are many reasons why sustainability is so difficult to achieve. These reasons have the name sustainability barriers.[5][16] Before addressing these barriers it is important to analyze and understand them.[5]: 34 Some barriers arise from nature and its complexity ("everything is related").[22] Others arise from the human condition. One example is the value-action gap. This reflects the fact that people often do not act according to their convictions. Experts describe these barriers as intrinsic to the concept of sustainability.[94]: 81

Other barriers are extrinsic to the concept of sustainability. This means it is possible to overcome them. One way would be to put a price tag on the consumption of public goods.[94]: 84 Some extrinsic barriers relate to the nature of dominant institutional frameworks. Examples would be where market mechanisms fail for public goods. Existing societies, economies, and cultures encourage increased consumption. There is a structural imperative for growth in competitive market economies. This inhibits necessary societal change.[87]

Furthermore, there are several barriers related to the difficulties of implementing sustainability policies. There are trade-offs between the goals of environmental policies and economic development. Environmental goals include nature conservation. Development may focus on poverty reduction.[16][5]: 65 There are also trade-offs between short-term profit and long-term viability.[94]: 65 Political pressures generally favor the short term over the long term. So they form a barrier to actions oriented toward improving sustainability.[94]: 86

Barriers to sustainability may also reflect current trends. These could include consumerism and short-termism.[94]: 86

The European Environment Agency defines a sustainability transition as "a fundamental and wide-ranging transformation of a socio-technical system towards a more sustainable configuration that helps alleviate persistent problems such as climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss or resource scarcities."[95]: 152 The concept of sustainability transitions is like the concept of energy transitions.[96]

One expert argues a sustainability transition must be "supported by a new kind of culture, a new kind of collaboration, [and] a new kind of leadership".[97] It requires a large investment in "new and greener capital goods, while simultaneously shifting capital away from unsustainable systems".[20]: 107 It prefers these to unsustainable options.[20]: 101

In 2024 an interdisciplinary group of experts including Chip Fletcher, William J. Ripple, Phoebe Barnard, Kamanamaikalani Beamer, Christopher Field, David Karl, David King, Michael E. Mann and Naomi Oreskes published the academic paper "Earth at Risk". They made an extensive review of existing scientific literature, placing the blame for the ecological crisis on "imperialism, extractive capitalism, and a surging population" and proposed a paradigm shift that replaces it with a socio-economic model prioritizing sustainability, resilience, justice, kinship with nature, and communal well-being. They described many ways in which the transition to a sustainabile future can be achieved.[98]

A sustainability transition requires major change in societies. They must change their fundamental values and organizing principles.[43]: 15 These new values would emphasize "the quality of life and material sufficiency, human solidarity and global equity, and affinity with nature and environmental sustainability".[43]: 15 A transition may only work if far-reaching lifestyle changes accompany technological advances.[87]

Scientists have pointed out that: "Sustainability transitions come about in diverse ways, and all require civil-society pressure and evidence-based advocacy, political leadership, and a solid understanding of policy instruments, markets, and other drivers."[50]

There are four possible overlapping processes of transformation. They each have different political dynamics. Technology, markets, government, or citizens can lead these processes.[21]

It is possible to divide action principles to make societies more sustainable into four types. These are nature-related, personal, society-related and systems-related principles.[5]: 206

There are many approaches that people can take to transition to environmental sustainability. These include maintaining ecosystem services, protecting and co-creating common resources, reducing food waste, and promoting dietary shifts towards plant-based foods.[99] Another is reducing population growth by cutting fertility rates. Others are promoting new green technologies, and adopting renewable energy sources while phasing out subsidies to fossil fuels.[50]

In 2017 scientists published an update to the 1992 World Scientists' Warning to Humanity. It showed how to move towards environmental sustainability. It proposed steps in three areas:[50]

In 2015, the United Nations agreed the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Their official name is Agenda 2030 for the Sustainable Development Goals. The UN described this programme as a very ambitious and transformational vision. It said the SDGs were of unprecedented scope and significance.[40]: 3/35

The UN said: "We are determined to take the bold and transformative steps which are urgently needed to shift the world on to a sustainable and resilient path."[40]

The 17 goals and targets lay out transformative steps. For example, the SDGs aim to protect the future of planet Earth. The UN pledged to "protect the planet from degradation, including through sustainable consumption and production, sustainably managing its natural resources and taking urgent action on climate change, so that it can support the needs of the present and future generations".[40]

Eco-economic decoupling is an idea to resolve tradeoffs between economic growth and environmental conservation. The idea is to "decouple environmental bads from economic goods as a path towards sustainability".[11] This would mean "using less resources per unit of economic output and reducing the environmental impact of any resources that are used or economic activities that are undertaken".[10]: 8 The intensity of pollutants emitted makes it possible to measure pressure on the environment. This in turn makes it possible to measure decoupling. This involves following changes in the emission intensity associated with economic output.[10] Examples of absolute long-term decoupling are rare. But some industrialized countries have decoupled GDP growth from production- and consumption-based CO2 emissions.[100] Yet, even in this example, decoupling alone is not enough. It is necessary to accompany it with "sufficiency-oriented strategies and strict enforcement of absolute reduction targets".[100]: 1

One study in 2020 found no evidence of necessary decoupling. This was a meta-analysis of 180 scientific studies. It found that there is "no evidence of the kind of decoupling needed for ecological sustainability" and that "in the absence of robust evidence, the goal of decoupling rests partly on faith".[11] Some experts have questioned the possibilities for decoupling and thus the feasibility of green growth.[12] Some have argued that decoupling on its own will not be enough to reduce environmental pressures. They say it would need to include the issue of economic growth.[12] There are several reasons why adequate decoupling is currently not taking place. These are rising energy expenditure, rebound effects, problem shifting, the underestimated impact of services, the limited potential of recycling, insufficient and inappropriate technological change, and cost-shifting.[12]

The decoupling of economic growth from environmental deterioration is difficult. This is because the entity that causes environmental and social costs does not generally pay for them. So the market price does not express such costs.[90] For example, the cost of packaging into the price of a product. may factor in the cost of packaging. But it may omit the cost of disposing of that packaging. Economics describes such factors as externalities, in this case a negative externality.[101] Usually, it is up to government action or local governance to deal with externalities.[102]

There are various ways to incorporate environmental and social costs and benefits into economic activities. Examples include: taxing the activity (the polluter pays); subsidizing activities with positive effects (rewarding stewardship); and outlawing particular levels of damaging practices (legal limits on pollution).[90]

A textbook on natural resources and environmental economics stated in 2011: "Nobody who has seriously studied the issues believes that the economy's relationship to the natural environment can be left entirely to market forces."[103]: 15 This means natural resources will be over-exploited and destroyed in the long run without government action.

Elinor Ostrom (winner of the 2009Nobel economics prize) expanded on this. She stated that local governance (or self-governance) can be a third option besides the market or the national government.[104] She studied how people in small, local communities manage shared natural resources.[105] She showed that communities using natural resources can establish rules their for use and maintenance. These are resources such as pastures, fishing waters, and forests. This leads to both economic and ecological sustainability.[104] Successful self-governance needs groups with frequent communication among participants. In this case, groups can manage the usage of common goods without overexploitation.[5]: 117 Based on Ostrom's work, some have argued that: "Common-pool resources today are overcultivated because the different agents do not know each other and cannot directly communicate with one another."[5]: 117

_Chapter_Indonesia_by_The_President_of_The_Republic_Indonesia_(10111448114).jpg/440px-Launching_of_The_UN_Sustainability_Development_Solution_Network_(SDSN)_Chapter_Indonesia_by_The_President_of_The_Republic_Indonesia_(10111448114).jpg)

Questions of global concern are difficult to tackle. That is because global issues need global solutions. But existing global organizations (UN, WTO, and others) do not have sufficient means.[5]: 135 For example, they lack sanctioning mechanisms to enforce existing global regulations.[5]: 136 Some institutions do not enjoy universal acceptance. An example is the International Criminal Court. Their agendas are not aligned (for example UNEP, UNDP, and WTO) And some accuse them of nepotism and mismanagement.[5]: 135–145

Multilateral international agreements, treaties, and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) face further challenges. These result in barriers to sustainability. Often these arrangements rely on voluntary commitments. An example is Nationally Determined Contributions for climate action. There can be a lack of enforcement of existing national or international regulation. And there can be gaps in regulation for international actors such as multi-national enterprises.Critics of some global organizations say they lack legitimacy and democracy. Institutions facing such criticism include the WTO, IMF, World Bank, UNFCCC, G7, G8 and OECD.[5]: 135

Sustainable business practices integrate ecological concerns with social and economic ones.[17][18] One accounting framework for this approach uses the phrase "people, planet, and profit". The name of this approach is the triple bottom line. The circular economy is a related concept. Its goal is to decouple environmental pressure from economic growth.[106][107]

Growing attention towards sustainability has led to the formation of many organizations. These include the Sustainability Consortium of the Society for Organizational Learning,[108] the Sustainable Business Institute,[109] and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development.[110] Supply chain sustainability looks at the environmental and human impacts of products in the supply chain. It considers how they move from raw materials sourcing to production, storage, and delivery, and every transportation link on the way.[111]

Religious leaders have stressed the importance of caring for nature and environmental sustainability. In 2015 over 150 leaders from various faiths issued a joint statement to the UN Climate Summit in Paris 2015.[112] They reiterated a statement made in the Interfaith Summit in New York in 2014:

As representatives from different faith and religious traditions, we stand together to express deep concern for the consequences of climate change on the earth and its people, all entrusted, as our faiths reveal, to our common care. Climate change is indeed a threat to life, a precious gift we have received and that we need to care for.[113]

Individuals can also live in a more sustainable way. They can change their lifestyles, practise ethical consumerism, and embrace frugality.[5]: 236 These sustainable living approaches can also make cities more sustainable. They do this by altering the built environment.[114] Such approaches include sustainable transport, sustainable architecture, and zero emission housing. Research can identify the main issues to focus on. These include flying, meat and dairy products, car driving, and household sufficiency. Research can show how to create cultures of sufficiency, care, solidarity, and simplicity.[87]

Some young people are using activism, litigation, and on-the-ground efforts to advance sustainability. This is particularly the case in the area of climate action.[66]: 60

Scholars have criticized the concepts of sustainability and sustainable development from different angles. One was Dennis Meadows, one of the authors of the first report to the Club of Rome, called "The Limits to Growth". He argued many people deceive themselves by using the Brundtland definition of sustainability.[52] This is because the needs of the present generation are actually not met today. Instead, economic activities to meet present needs will shrink the options of future generations.[115][5]: 27 Another criticism is that the paradigm of sustainability is no longer suitable as a guide for transformation. This is because societies are "socially and ecologically self-destructive consumer societies".[116]

Some scholars have even proclaimed the end of the concept of sustainability. This is because humans now have a significant impact on Earth's climate system and ecosystems.[19] It might become impossible to pursue sustainability because of these complex, radical, and dynamic issues.[19] Others have called sustainability a utopian ideal: "We need to keep sustainability as an ideal; an ideal which we might never reach, which might be utopian, but still a necessary one."[5]: 5

The term is often hijacked and thus can lose its meaning. People use it for all sorts of things, such as saving the planet to recycling your rubbish.[26] A specific definition may never be possible. This is because sustainability is a concept that provides a normative structure. That describes what human society regards as good or desirable.[2]

But some argue that while sustainability is vague and contested it is not meaningless.[2] Although lacking in a singular definition, this concept is still useful. Scholars have argued that its fuzziness can actually be liberating. This is because it means that "the basic goal of sustainability (maintaining or improving desirable conditions [...]) can be pursued with more flexibility".[22]

Sustainability has a reputation as a buzzword.[1] People may use the terms sustainability and sustainable development in ways that are different to how they are usually understood. This can result in confusion and mistrust. So a clear explanation of how the terms are being used in a particular situation is important.[22]

Greenwashing is a practice of deceptive marketing. It is when a company or organization provides misleading information about the sustainability of a product, policy, or other activity.[66]: 26 [117] Investors are wary of this issue as it exposes them to risk.[118] The reliability of eco-labels is also doubtful in some cases.[119] Ecolabelling is a voluntary method of environmental performance certification and labelling for food and consumer products. The most credible eco-labels are those developed with close participation from all relevant stakeholders.[120]

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link){{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)