Дамаск ( араб . دِمَشق , романизировано : Dimašq ) — столица и крупнейший город Сирии , старейшая нынешняя столица в мире и , по некоторым данным , четвёртый по святости город в исламе . [10] [11] [12] Известный в Сирии как аш-Шам ( الشَّام ) и поэтически называемый «Городом жасмина » ( مَدِيْنَةُ الْيَاسْمِينِ Madīnat al-Yāsmīn ), [1] Дамаск является крупным культурным центром Леванта и арабского мира . Расположенный на юго-западе Сирии, Дамаск является центром большого мегаполиса. Расположенный среди восточных предгорий горного хребта Антиливан , в 80 километрах (50 миль) от восточного побережья Средиземного моря на плато высотой 680 метров (2230 футов) над уровнем моря , Дамаск испытывает засушливый климат из-за эффекта дождевой тени . Река Барада протекает через Дамаск.

Дамаск — один из старейших постоянно населенных городов в мире . [13] Впервые основанный в 3-м тысячелетии до н. э., он был выбран столицей Омейядского халифата с 661 по 750 год. После победы династии Аббасидов резиденция исламской власти была перенесена в Багдад . Значение Дамаска снижалось на протяжении всей эпохи Аббасидов, но затем вновь обрело значительное значение в периоды Айюбидов и мамлюков . Сегодня это резиденция центрального правительства Сирии. Дамаск серьезно пострадал от гражданской войны в Сирии , которая началась в 2011 году. Город подвергся многочисленным бомбардировкам во время войны и был полем битвы между оппозиционными группами и правительственными войсками. В 2018 году сирийское правительство вернуло себе весь город.

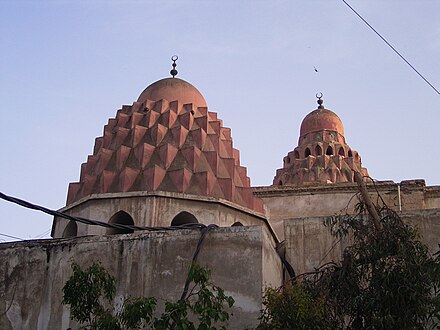

По состоянию на сентябрь 2019 года [update], спустя восемь лет после начала войны, Дамаск был назван наименее пригодным для жизни городом из 140 городов мира в Глобальном рейтинге удобства для жизни . [14] По состоянию на июнь 2023 года [update]он был наименее пригодным для жизни из 173 городов мира в том же Глобальном рейтинге удобства для жизни. В 2017 году в Дамаске были запущены новые проекты по строительству новых жилых районов, символизирующих послевоенное восстановление. [15] Старый город Дамаска широко известен многочисленными достопримечательностями, включая мечеть Омейядов , мавзолей Саладина , еврейский квартал , собор Святого Георгия и мечеть Сайида Рукайя .

Название Дамаск впервые появилось в географическом списке Тутмоса III как ṯmśq ( 𓍘𓄟𓊃𓈎𓅱 ) в 15 веке до н. э. [17] Этимология древнего названия ṯmśq неизвестна. Оно засвидетельствовано как Имеришу ( 𒀲𒋙 ) на аккадском языке , ṯmśq ( 𓍘𓄟𓊃𓈎𓅱 ) на египетском языке , Дамашк ( 𐡃𐡌𐡔𐡒 ) на древнеарамейском языке и Даммесек ( דַּמֶּשֶׂק ) на библейском иврите . Ряд аккадских вариантов написания встречается в амарнских письмах XIV века до н. э.: Dimašqa ( 𒁲𒈦𒋡 ), Dimašqì ( 𒁲𒈦𒀸𒄀 ) и Dimašqa ( 𒁲𒈦𒀸𒋡 ).

Более поздние арамейские написания названия часто включают в себя навязчивую реш (букву r ), возможно, под влиянием корня dr , означающего «жилище». Таким образом, английское и латинское название города — Damascus , которое было заимствовано из греческого Δαμασκός и произошло от кумранского Darmeśeq ( דרמשק ), и Darmsûq ( ܕܪܡܣܘܩ ) на сирийском языке , [18] [19] что означает «хорошо орошаемая земля». [20]

На арабском языке город называется Димашк ( دمشق Dimašq ). [21] Город также известен как аш-Шам гражданами Дамаска, Сирии и других арабских соседей и Турции ( eş-Şam ). Аш-Шам — это арабский термин для « Леванта » и для «Сирии»; последний, и в частности историческая область Сирии , называется Билад аш-Шам ( بلاد الشام , букв. « земля Леванта » ). [примечание 2] Последний термин этимологически означает «земля левой стороны» или «север», так как кто-то в Хиджазе , глядя на восток, ориентируясь на восход солнца, обнаружит север слева. Это контрастирует с названием Йемен ( اَلْيَمَن al-Yaman ), что соответственно означает «правая сторона» или «юг». Вариант ش ء م ( š-ʾ-m '), более типичного ش م ل ( š-ml ), также засвидетельствован в древнеюжноаравийском , 𐩦𐩱𐩣 ( šʾm ), с тем же семантическим развитием. [26] [27]

Дамаск был построен в стратегическом месте на плато на высоте 680 м (2230 футов) над уровнем моря и примерно в 80 км (50 миль) от Средиземного моря, защищенный горами Антиливан , снабжаемый водой из реки Барада , и на перекрестке торговых путей: маршрута с севера на юг, соединяющего Египет с Малой Азией , и маршрута через пустыню с востока на запад, соединяющего Ливан с долиной реки Евфрат . Горы Антиливан обозначают границу между Сирией и Ливаном. Хребет имеет вершины высотой более 10 000 футов (3000 м) и блокирует осадки из Средиземного моря, поэтому район Дамаска иногда подвержен засухам. Однако в древние времена река Барада смягчала это, которая берет начало из горных ручьев, питаемых тающим снегом. Дамаск окружен Гутой , орошаемой сельскохозяйственной землей, где с древних времен выращивалось много овощей, злаков и фруктов. Карты римской Сирии показывают, что река Барада впадала в озеро определенного размера к востоку от Дамаска. Сегодня оно называется Бахира Атайба, колеблющееся озеро, потому что в годы сильной засухи оно даже не существует. [28]

Современный город имеет площадь 105 км 2 (41 кв. милю), из которых 77 км 2 (30 кв. миль) занимают городские районы, а остальную часть занимает Джабаль-Касиун . [29]

.jpg/440px-Barada_river_in_Damascus_(April_2009).jpg)

Старый город Дамаска, окруженный городскими стенами, расположен на южном берегу реки Барада , которая почти высохла (3 см (1 дюйм) слева). На юго-востоке, севере и северо-востоке он окружен пригородными районами, история которых восходит к Средним векам: Мидан на юго-западе, Саруджа и Имара на севере и северо-западе. Эти кварталы изначально возникли на дорогах, ведущих из города, недалеко от могил религиозных деятелей. В 19 веке отдаленные деревни развивались на склонах Джабаль Касиун , возвышаясь над городом, уже на месте района ас-Салихия, сосредоточенного вокруг важной святыни средневекового андалузского шейха и философа Ибн Араби . Эти новые кварталы изначально были заселены курдскими солдатами и мусульманскими беженцами из европейских регионов Османской империи , которые попали под христианское правление. Поэтому они были известны как аль-Акрад (курды) и аль-Мухаджирин (мигранты) . Они располагались в 2–3 км к северу от старого города.

С конца 19 века к западу от старого города, вокруг Барады, начал возникать современный административный и торговый центр, сосредоточенный в районе, известном как аль-Марджех или «луг». Аль-Марджех вскоре стал названием того, что изначально было центральной площадью современного Дамаска, с городской ратушей на ней. Суды, почта и железнодорожная станция стояли на возвышенности немного южнее. Вскоре на дороге, ведущей между аль-Марджехом и аль-Салихией , начал строиться европеизированный жилой квартал . Коммерческий и административный центр нового города постепенно сместился немного на север в сторону этой области.

В 20 веке новые пригороды развивались к северу от Барады и в некоторой степени к югу, вторгаясь в оазис Гута . [ требуется цитата ] В 1956–1957 годах новый район Ярмук стал вторым домом для многих палестинских беженцев. [30] Городские планировщики предпочитали сохранять Гуту насколько это было возможно, и в конце 20 века некоторые из основных районов развития находились на севере, в западном районе Меззе и совсем недавно вдоль долины Барада в Думмаре на северо-западе и на склонах гор в Барзе на северо-востоке. Более бедные районы, часто построенные без официального одобрения, в основном развивались к югу от главного города.

Дамаск раньше был окружен оазисом , регионом Гута ( араб . الغوطة , романизировано : al-ġūṭä ), орошаемым рекой Барада. Источник Фиджех , на западе долины Барада, использовался для обеспечения города питьевой водой, а различные источники на западе используются подрядчиками по водоснабжению. Поток Барады снизился из-за быстрого расширения жилищного строительства и промышленности в городе, и он почти высох. Нижние водоносные горизонты загрязнены городскими стоками с интенсивно используемых дорог, промышленности и канализации.

В Дамаске прохладный засушливый климат ( BWk ) в системе Кеппен-Гейгера [ 31] из-за эффекта дождевой тени Антиливанских гор [32] и преобладающих океанических течений. Лето продолжительное, сухое и жаркое с меньшей влажностью. Зима прохладная и несколько дождливая; снегопады редки. Осень короткая и мягкая, но имеет самые резкие перепады температур, в отличие от весны, где переход к лету более постепенный и устойчивый. Годовое количество осадков составляет около 130 мм (5 дюймов), с октября по май.

Радиоуглеродное датирование в Телль-Рамаде , на окраине Дамаска, позволяет предположить, что это место могло быть заселено со второй половины седьмого тысячелетия до нашей эры, возможно, около 6300 года до нашей эры. [35] Однако существуют свидетельства поселения в более широком бассейне Барада, датируемые 9000 годом до нашей эры, хотя никаких крупных поселений в пределах стен Дамаска не было до второго тысячелетия до нашей эры. [36]

Некоторые из самых ранних египетских записей относятся к 1350 г. до н. э. письмам Амарны , когда Дамаском (называемым Димаск ) правил царь Бирьяваза . Регион Дамаска, как и остальная часть Сирии, стал полем битвы около 1260 г. до н. э. между хеттами с севера и египтянами с юга, [37] закончившимся подписанием договора между Хаттусили III и Рамсесом II , по которому первый передал контроль над районом Дамаска Рамсесу II в 1259 г. до н. э. [37] Прибытие народов моря около 1200 г. до н. э. ознаменовало конец бронзового века в регионе и привело к новому развитию войны. [38] Дамаск был лишь периферийной частью этой картины, которая в основном затронула более крупные населенные пункты древней Сирии. Однако эти события способствовали развитию Дамаска как нового влиятельного центра, возникшего с переходом от бронзового века к железному веку . [38]

Дамаск упоминается в Бытии 14:15 как существующий во времена Войны царей . [39] Согласно еврейскому историку I века Иосифу Флавию в его двадцати одном томе «Иудейские древности» , Дамаск (вместе с Трахонитидой ) был основан Уцем , сыном Арама . [40] В «Древностях» i. 7, [41] Иосиф Флавий сообщает:

Николай Дамаскин в четвертой книге своей «Истории» говорит так: « Авраам царствовал в Дамаске, будучи иноземцем, пришедшим с войском из земли, лежащей выше Вавилона , называемой землей Халдейской; но после долгого времени он встал и двинулся из этой страны вместе со своим народом и пошел в землю, тогда называемую землей Ханаанской , а теперь землей Иудейской, и это когда его потомство стало многочисленным; об этом его потомстве мы рассказываем их историю в другом труде. Имя Авраама до сих пор известно в стране Дамаска; и есть деревня, названная в его честь — Обитель Авраама».

Дамаск впервые упоминается как важный город во время прибытия арамеев , семитского народа , в 11 веке до нашей эры. К началу первого тысячелетия до нашей эры образовалось несколько арамейских царств, поскольку арамеи отказались от своего кочевого образа жизни и образовали федеративные племенные государства. Одним из этих царств был Арам-Дамаск , со столицей Дамаск. [43] Арамеи, вошедшие в город без боя, приняли название «Димашку» для своего нового дома. Заметив сельскохозяйственный потенциал все еще неразвитой и малонаселенной области, [44] они создали систему распределения воды Дамаска, построив каналы и туннели, которые максимально увеличили эффективность реки Барада. Римляне и Омейяды позже улучшили ту же сеть, и она до сих пор составляет основу системы водоснабжения старой части города сегодня. [45] Арамеи изначально превратили Дамаск в форпост свободной федерации арамейских племен, известной как Арам-Зоба , базировавшейся в долине Бекаа . [44]

Город приобрел превосходство в южной Сирии, когда Эзрон , претендент на трон Арам-Цобаха, которому было отказано в праве на царствование в федерации, бежал из Бекаа и силой захватил Дамаск в 965 г. до н. э. Эзрон сверг племенного губернатора города и основал независимое образование Арам-Дамаск. Поскольку это новое государство расширялось на юг, оно помешало Царству Израиля распространяться на север, и два царства вскоре столкнулись, поскольку они оба стремились доминировать в торговой гегемонии на востоке. [44] При внуке Эзрона, Бен-Хададе I (880–841 гг. до н. э.), и его преемнике Азаиле , Дамаск присоединил Васан (современный регион Хауран ) и перешел в наступление с Израилем. Этот конфликт продолжался до начала VIII в. до н. э., когда Бен-Хадад II был захвачен Израилем после безуспешной осады Самарии . В результате он предоставил Израилю торговые права в Дамаске. [46]

Другой возможной причиной договора между Арамом-Дамаском и Израилем была общая угроза со стороны Неоассирийской империи , которая пыталась расшириться на побережье Средиземного моря. В 853 г. до н. э. царь Дамаска Хададезер возглавил левантийскую коалицию, в которую вошли силы из северного Арам-Хамафа и войска, предоставленные царем Израиля Ахавом , в битве при Каркаре против неоассирийской армии. Арам-Дамаск вышел победителем, временно предотвратив вторжение ассирийцев в Сирию. Однако после того, как Хададезер был убит своим преемником Азаилом, левантийский союз распался. Арам-Дамаск попытался вторгнуться в Израиль, но был прерван возобновившимся ассирийским вторжением. Азаил приказал отступить в обнесенную стеной часть Дамаска, в то время как ассирийцы разграбили оставшуюся часть царства. Не имея возможности войти в город, они объявили о своем господстве в долинах Хауран и Бекаа. [46]

К VIII веку до н. э. Дамаск был практически захвачен ассирийцами и вступил в Темные века. Тем не менее, он оставался экономическим и культурным центром Ближнего Востока, а также арамейского сопротивления. В 727 году в городе произошло восстание, которое было подавлено ассирийскими войсками. После того, как Ассирия во главе с Тиглатпаласаром III начала широкомасштабную кампанию по подавлению восстаний по всей Сирии, Дамаск оказался под их правлением. Положительным эффектом этого стала стабильность для города и выгоды от торговли пряностями и благовониями с Аравией . В 694 году до н. э. город назывался Ша'имеришу (аккад. 𒐼𒄿𒈨𒊑𒋙𒌋), а его губернатором был назван Илу-иссия . [47] Однако ассирийская власть ослабла к 609–605 гг. до н. э., и Сирия-Палестина попала в орбиту Египта фараона Нехо II . В 572 г. до н. э. вся Сирия была завоевана Навуходоносором II из нововавилонян , но статус Дамаска под Вавилоном относительно неизвестен. [48]

Дамаск был завоеван Александром Македонским . После смерти Александра в 323 г. до н. э. Дамаск стал местом борьбы между империями Селевкидов и Птолемеев . Контроль над городом часто переходил от одной империи к другой. Селевк I Никатор , один из генералов Александра, сделал Антиохию столицей своей огромной империи, что привело к снижению значимости Дамаска по сравнению с новыми городами Селевкидов, такими как сирийская Лаодикия на севере. Позже Деметрий III Филопатор перестроил город в соответствии с греческой системой ипподамиан и переименовал его в «Деметриада». [49]

В 64 г. до н. э. римский полководец Помпей аннексировал западную часть Сирии. Римляне заняли Дамаск и впоследствии включили его в союз десяти городов, известный как Декаполис [50] , которые сами были включены в провинцию Сирия и получили автономию. [51]

Город Дамаск был полностью перестроен римлянами после того, как Помпей завоевал регион. До сих пор Старый город Дамаска сохраняет прямоугольную форму римского города с двумя основными осями: Decumanus Maximus (восток-запад; сегодня известный как Via Recta ) и Cardo (север-юг), причем Decumanus был примерно в два раза длиннее. Римляне построили монументальные ворота, которые все еще сохранились в восточном конце Decumanus Maximus. Первоначально ворота имели три арки: центральная арка была для колесниц, а боковые арки были для пешеходов. [28]

В 23 г. до н. э. Ироду Великому цезарь Август передал земли, контролируемые Зенодором [52], и некоторые ученые полагают, что Ироду также был предоставлен контроль над Дамаском. [53] Контроль над Дамаском вернулся к Сирии либо после смерти Ирода Великого, либо был частью земель, данных Ироду Филиппу, которые были переданы Сирии после его смерти в 33/34 г. н. э.

Предполагается, что контроль над Дамаском был получен Аретой IV Филопатрисом Набатейским между смертью Ирода Филиппа в 33/34 г. н. э . и смертью Ареты в 40 г. н. э., но есть существенные доказательства против того, что Арета контролировал город до 37 г. н. э., и много причин, по которым это не могло быть подарком от Калигулы между 37 и 40 г. н. э. [54] [55] На самом деле, все эти теории исходят не из каких-либо фактических доказательств за пределами Нового Завета, а скорее из «определенного понимания 2 Коринфянам 11:32», и в действительности «ни археологические свидетельства, ни светско-исторические источники, ни тексты Нового Завета не могут доказать набатейский суверенитет над Дамаском в первом веке н. э.». [56] Римский император Траян, который аннексировал Набатейское царство, создав провинцию Аравия Петрея , ранее бывал в Дамаске, так как его отец Марк Ульпий Траян служил губернатором Сирии с 73 по 74 год н. э., где он встретил набатейского архитектора и инженера Аполлодора Дамасского , который присоединился к нему в Риме , когда он был консулом в 91 году н. э., и позже построил несколько памятников во II веке н. э. [57]

Дамаск стал метрополией к началу II века, а в 222 году император Септимий Север повысил его до колонии . Во время Pax Romana Дамаск и римская провинция Сирия в целом начали процветать. Важность Дамаска как караванного города была очевидна, поскольку торговые пути из южной Аравии , Пальмиры , Петры и шелковые пути из Китая сходились в нем. Город удовлетворял римские потребности в восточной роскоши. Около 125 года н. э. римский император Адриан повысил город Дамаск до «метрополия Келесирии ». [58] [59]

От архитектуры римлян мало что осталось, но городское планирование старого города имело долгосрочный эффект. Римские архитекторы объединили греческие и арамейские основы города и объединили их в новую планировку размером примерно 1500 на 750 м (4920 на 2460 футов), окруженную городской стеной. Городская стена имела семь ворот, но только восточные ворота, Баб Шарки , сохранились от римского периода. Римский Дамаск в основном находится на глубине до пяти метров (16 футов) под современным городом.

Старый район Баб-Тума был основан в конце римско-византийской эпохи местной православной общиной. Согласно Деяниям апостолов , в этом районе жили Святой Павел и Святой Фома . Римско-католические историки также считают Баб-Туму местом рождения нескольких Пап, таких как Иоанн V и Григорий III . Соответственно, существовала община иудеев-христиан , которые обратились в христианство с приходом прозелитизма Святого Павла.

Во время византийско-сасанидской войны 602–628 годов город был осажден и захвачен Шахрбаразом в 613 году вместе с большим количеством византийских войск в качестве пленников [60] и находился в руках Сасанидов почти до конца войны. [61]

Первое косвенное взаимодействие Мухаммеда с жителями Дамаска произошло, когда он отправил письмо через своего товарища Шию ибн Вахаба Хариту ибн Аби Шамиру , королю Дамаска. В своем письме Мухаммед заявил: «Мир тому, кто следует истинному руководству. Знайте, что моя религия будет преобладать повсюду. Вам следует принять ислам, и все, что находится под вашим командованием, останется вашим». [62] [63]

После того, как большая часть сирийской сельской местности была завоевана халифатом Рашидун во время правления халифа Умара ( р. 634–644 ), сам Дамаск был завоеван арабским мусульманским генералом Халидом ибн аль-Валидом в августе-сентябре 634 г. н. э. Его армия ранее пыталась захватить город в апреле 634 г., но безуспешно. [64] Теперь, когда Дамаск оказался в руках мусульман-арабов, византийцы, встревоженные потерей своего самого престижного города на Ближнем Востоке, решили вернуть себе контроль над ним. При императоре Ираклии византийцы выставили армию, превосходящую армию Рашидун по численности. Они продвинулись в южную Сирию весной 636 г., и впоследствии войска Халида ибн аль-Валида отступили из Дамаска, чтобы подготовиться к новому противостоянию. [65] В августе обе стороны встретились у реки Ярмук , где они сразились в крупном сражении , которое закончилось решительной победой мусульман, укрепив мусульманское правление в Сирии и Палестине. [66] В то время как мусульмане управляли городом, население Дамаска оставалось в основном христианским — православным и монофизитским — с растущей общиной мусульман из Мекки , Медины и Сирийской пустыни . [67] Губернатором, назначенным в город, который был выбран в качестве столицы исламской Сирии, был Муавия I.

После смерти четвертого халифа-рашидуна Али в 661 году Муавия был избран халифом расширяющейся исламской империи. Из-за огромного количества активов, которыми владел его клан, Омейяды , в городе и из-за его традиционных экономических и социальных связей с Хиджазом, а также христианскими арабскими племенами региона, Муавия сделал Дамаск столицей всего халифата . [68] С восхождением халифа Абд аль-Малика в 685 году была введена исламская система чеканки монет, и все излишки доходов провинций халифата были направлены в казну Дамаска. Арабский язык также был установлен в качестве официального языка, что дало мусульманскому меньшинству города преимущество перед христианами, говорящими на арамейском языке, в административных делах. [69]

Преемник Абд аль-Малика , аль-Валид, инициировал строительство Большой мечети Дамаска (известной как мечеть Омейядов) в 706 году. Первоначально на этом месте находился христианский собор Святого Иоанна, и мусульмане сохранили посвящение здания Иоанну Крестителю . [70] К 715 году мечеть была завершена. Аль-Валид умер в том же году, и его преемником стал сначала Сулейман ибн Абд аль-Малик , а затем Умар II , каждый из которых правил в течение коротких периодов до правления Хишама в 724 году. С этими преемниками статус Дамаска постепенно ослабевал, поскольку Сулейман выбрал Рамлу своей резиденцией, а позже Хишам выбрал Ресафу . После убийства последнего в 743 году халифат Омейядов, который к тому времени простирался от Испании до Индии, начал рушиться в результате широкомасштабных восстаний. Во время правления Марвана II в 744 году столица империи была перенесена в Харран в северном регионе Джазира . [71]

25 августа 750 года Аббасиды , уже разгромившие Омейядов в битве при Забе в Ираке, захватили Дамаск, не встретив особого сопротивления. С провозглашением Аббасидского халифата Дамаск оказался в тени и подчинен Багдаду , новой исламской столице. В течение первых шести месяцев правления Аббасидов в городе начали вспыхивать восстания, хотя они были слишком изолированы и нецеленаправлены, чтобы представлять реальную угрозу. Тем не менее, последний из видных Омейядов был казнен, традиционные должностные лица Дамаска подверглись остракизму, а генералы армии города были уволены. После этого семейное кладбище Омейядов было осквернено, а городские стены снесены, что превратило Дамаск в провинциальный городок малой важности. Он практически исчез из письменных источников на следующее столетие, и единственным значительным улучшением города стал построенный Аббасидами купол сокровищницы в мечети Омейядов в 789 году. В 811 году отдаленные остатки династии Омейядов устроили сильное восстание в Дамаске, которое в конечном итоге было подавлено. [72]

24 ноября 847 года сильное землетрясение разрушило Дамаск , в результате чего погибло около 70 000 человек.

Ахмад ибн Тулун , несогласный турецкий вали, назначенный Аббасидами, завоевал Сирию, включая Дамаск, у своих повелителей в 878–79 годах. В знак уважения к предыдущим правителям Омейядов он воздвиг святыню на месте могилы Муавии в городе. Правление Тулунидов в Дамаске было недолгим и длилось только до 906 года, прежде чем их сменили карматы , приверженцы шиитского ислама . Из-за своей неспособности контролировать огромное количество земель, которые они занимали, карматы покинули Дамаск, и новая династия, Ихшидиды , взяла под свой контроль город. Они сохранили независимость Дамаска от арабской династии Хамданидов в Алеппо в 967 году. Затем последовал период нестабильности в городе: набег карматов в 968 году, набег византийцев в 970 году и усиливающееся давление со стороны Фатимидов на юге и Хамданидов на севере. [73]

Шииты Фатимиды получили контроль в 970 году, разжигая враждебность между ними и суннитскими арабами города, которые часто восставали. Турок Альптакин изгнал Фатимидов пять лет спустя и с помощью дипломатии предотвратил попытку византийцев во время сирийских кампаний Иоанна Цимисхия аннексировать город. Однако к 977 году Фатимиды под руководством халифа аль-Азиза вернули себе контроль над городом и усмирили суннитских диссидентов. Арабский географ аль-Мукаддаси посетил Дамаск в 985 году, отметив, что архитектура и инфраструктура города были «великолепными», но условия жизни были ужасными. При аль-Азизе город пережил краткий период стабильности, который закончился с правлением аль-Хакима (996–1021). В 998 году сотни граждан Дамаска были окружены и казнены им за подстрекательство. Через три года после таинственного исчезновения аль-Хакима в южной Сирии началось восстание против Фатимидов, но было подавлено фатимидским турецким наместником Сирии и Палестины Ануштакином ад-Дузбари в 1029 году. Эта победа дала последнему господство над Сирией, что вызвало недовольство его фатимидских сюзеренов, но завоевало восхищение граждан Дамаска. Он был сослан фатимидскими властями в Алеппо , где и умер в 1041 году . [74] С этой даты по 1063 год нет никаких известных записей об истории города. К тому времени в Дамаске не было городской администрации, экономика была ослаблена, а население значительно сократилось. [75]

С приходом турок-сельджуков в конце XI века Дамаск снова стал столицей независимых государств. С 1079 года им правил Абу Саид Тадж ад-Даула Тутуш I , а в 1095 году его сменил его сын Абу Наср Дукак . Сельджуки основали в Дамаске двор и систематически пресекали вторжения шиитов в город. В городе также наблюдалось расширение религиозной жизни за счет частных пожертвований, финансирующих религиозные учреждения ( медресе ) и больницы ( маристаны ). Вскоре Дамаск стал одним из важнейших центров распространения исламской мысли в мусульманском мире. После смерти Дукака в 1104 году его наставник ( атабег ) Тогтекин взял под контроль Дамаск и линию Буридов династии Сельджуков. При Дукаке и Тогтекине Дамаск испытал стабильность, возросший статус и возрожденную роль в торговле. Кроме того, суннитское большинство города наслаждалось тем, что было частью более крупной суннитской структуры, эффективно управляемой различными тюркскими династиями, которые, в свою очередь, находились под моральным авторитетом Аббасидов, базировавшихся в Багдаде. [76]

Пока правители Дамаска были заняты конфликтом со своими собратьями-сельджуками в Алеппо и Диярбакыре , крестоносцы, прибывшие в Левант в 1097 году, завоевали Иерусалим , Ливанскую гору и Палестину. Дукак, казалось, был доволен правлением крестоносцев в качестве буфера между его владениями и Фатимидским халифатом Египта. Однако Тогтекин видел в западных захватчиках реальную угрозу Дамаску, который в то время номинально включал Хомс , долину Бекаа, Хауран и Голанские высоты как часть своих территорий. При военной поддержке Шарафа ад-Дина Маудуда из Мосула Тогтекин сумел остановить набеги крестоносцев на Голаны и Хауран. Маудуд был убит в мечети Омейядов в 1109 году, что лишило Дамаск поддержки северных мусульман и вынудило Тугтекина согласиться на перемирие с крестоносцами в 1110 году. [77] В 1126 году армия крестоносцев под предводительством Балдуина II сражалась с войсками Буридов во главе с Тугтекином в Мардж аль-Саффар недалеко от Дамаска; однако, несмотря на тактическую победу, крестоносцы не смогли достичь своей цели по захвату Дамаска.

После смерти Тогтекина в 1128 году его сын Тадж аль-Мулук Бури стал номинальным правителем Дамаска. По совпадению, сельджукский принц Мосула Имад ад-Дин Зенги захватил власть в Алеппо и получил мандат от Аббасидов на распространение своей власти на Дамаск. В 1129 году в городе было убито около 6000 мусульман-исмаилитов вместе со своими лидерами. Суннитов спровоцировали слухи о заговоре исмаилитов, контролировавших стратегический форт в Баниасе , с целью помочь крестоносцам захватить Дамаск в обмен на контроль над Тиром . Вскоре после резни крестоносцы решили воспользоваться нестабильной ситуацией и начать наступление на Дамаск с почти 2000 рыцарей и 10 000 пехотинцев. Однако Бури объединился с Зенги и сумел помешать их армии достичь города. [80] Бури был убит агентами исмаилитов в 1132 году; ему наследовал его сын, Шамс аль-Мульк Исмаил , который правил тиранией, пока не был убит в 1135 году по тайному приказу своей матери, Сафват аль-Мульк Зумурруд ; брат Исмаила, Шихаб ад-Дин Махмуд, заменил его. Тем временем Зенги, намереваясь взять Дамаск под свой контроль, женился на Сафват аль-Мульк в 1138 году. Правление Махмуда затем закончилось в 1139 году после того, как он был убит по относительно неизвестным причинам членами своей семьи. Муин ад-Дин Унур , его мамлюк («раб-солдат»), взял под контроль город, побудив Зенги — при поддержке Сафвата аль-Мулька — осадить Дамаск в том же году. В ответ Дамаск объединился с Иерусалимским королевством крестоносцев , чтобы противостоять силам Зенги. В результате Зенги отозвал свою армию и сосредоточился на походах против северной Сирии. [81]

В 1144 году Зенги завоевал Эдессу , оплот крестоносцев, что привело к новому крестовому походу из Европы в 1148 году. Тем временем Зенги был убит, а его территория была разделена между его сыновьями, один из которых, Нур ад-Дин , эмир Алеппо, заключил союз с Дамаском. Когда прибыли европейские крестоносцы, они и дворяне Иерусалима согласились атаковать Дамаск. Однако их осада потерпела полный провал. Когда город, казалось, был на грани краха, армия крестоносцев внезапно двинулась против другого участка стен и была отброшена. К 1154 году Дамаск был прочно под контролем Нур ад-Дина. [82]

В 1164 году король Амори из Иерусалима вторгся в Египет Фатимидов , запросил помощи у Нур ад-Дина. Нур ад-Дин послал своего генерала Ширкуха , и в 1166 году Амори был побежден в битве при аль-Бабайне . Когда Ширкух умер в 1169 году, его преемником стал его племянник Юсуф, более известный как Саладин , который победил совместную осаду Дамиетты крестоносцами и византийцами . [83] Саладин в конечном итоге сверг халифов Фатимидов и утвердился в качестве султана Египта. Он также начал утверждать свою независимость от Нур ад-Дина, и со смертью как Аморика, так и Нур ад-Дина в 1174 году он оказался в выгодном положении, чтобы начать осуществлять контроль над Дамаском и другими сирийскими владениями Нур ад-Дина. [84] В 1177 году Саладин был побеждён крестоносцами в битве при Монжизаре , несмотря на своё численное превосходство. [85] Саладин также осадил Керак в 1183 году, но был вынужден отступить. Наконец, он начал полное вторжение в Иерусалим в 1187 году и уничтожил армию крестоносцев в битве при Хаттине в июле. Вскоре после этого Саладин захватил Акр , а сам Иерусалим был захвачен в октябре. Эти события потрясли Европу, что привело к Третьему крестовому походу в 1189 году под предводительством Ричарда I Английского , Филиппа II Французского и Фридриха I, императора Священной Римской империи , хотя последний утонул по пути. [86]

Выжившие крестоносцы, к которым присоединились вновь прибывшие из Европы, подвергли Акру длительной осаде , которая продолжалась до 1191 года. После повторного захвата Акры Ричард победил Саладина в битве при Арсуфе в 1191 году и битве при Яффе в 1192 году, вернув большую часть побережья для христиан, но не смог вернуть Иерусалим или какую-либо внутреннюю территорию королевства. Крестовый поход закончился мирно, с Яффским договором в 1192 году. Саладин разрешил совершать паломничества в Иерусалим, позволив крестоносцам выполнить свои обеты, после чего они все вернулись домой. Местные бароны-крестоносцы начали восстанавливать свое королевство из Акры и других прибрежных городов. [87]

Саладин умер в 1193 году, и между различными султанами Айюбидов, правившими в Дамаске и Каире, часто происходили конфликты . Дамаск был столицей независимых правителей Айюбидов между 1193 и 1201, с 1218 по 1238, с 1239 по 1245 и с 1250 по 1260. В другие времена им правили правители Айюбиды Египта. [88] Во время междоусобных войн, которые вели правители Айюбиды, Дамаск неоднократно подвергался осаде, как, например, в 1229 году . [89]

The patterned Byzantine and Chinese silks available through Damascus, one of the Western termini of the Silk Road, gave the English language "damask".[90]

Ayyubid rule (and independence) came to an end with the Mongol invasion of Syria in 1260, in which the Mongols led by Kitbuqa entered the city on 1 March 1260, along with the King of Armenia, Hethum I, and the Prince of Antioch, Bohemond VI; hence, the citizens of Damascus saw for the first time for six centuries three Christian potentates ride in triumph through their streets.[91] However, following the Mongol defeat at Ain Jalut on 3 September 1260, Damascus was captured five days later and became the provincial capital of the Mamluk Sultanate, ruled from Egypt, following the Mongol withdrawal. Following their victory at the Battle of Wadi al-Khaznadar, the Mongols led by Ghazan besieged the city for ten days, which surrendered between December 30, 1299, and January 6, 1300, though its Citadel resisted.[92] Ghazan then retreated with most of his forces in February, probably because the Mongol horses needed fodder, and left behind about 10,000 horsemen under the Mongol general Mulay.[93] Around March 1300, Mulay returned with his horsemen to Damascus,[94] then followed Ghazan back across the Euphrates. In May 1300, the Egyptian Mamluks returned from Egypt and reclaimed the entire area[95] without a battle.[96] In April 1303, the Mamluks managed to defeat the Mongol army led by Kutlushah and Mulay along with their Armenian allies at the Battle of Marj al-Saffar, to put an end to Mongol invasions of the Levant.[97] Later on, the Black Death of 1348–1349 killed as much as half of the city's population.[98]

In 1400, Timur, the Turco-Mongol conqueror, besieged Damascus. The Mamluk sultan dispatched a deputation from Cairo, including Ibn Khaldun, who negotiated with him, but after their withdrawal, Timur sacked the city on 17 March 1401.[99] The Umayyad Mosque was burnt and men and women were taken into slavery. A huge number of the city's artisans were taken to Timur's capital at Samarkand. These were the luckier citizens: many were slaughtered and their heads piled up in a field outside the north-east corner of the walls, where a city square still bears the name Burj al-Ru'us (between modern-day Al-Qassaa and Bab Tuma), originally "the tower of heads".

Rebuilt, Damascus continued to serve as a Mamluk provincial capital until 1516.

_(14578799080).jpg/440px-The_universal_geography_-_the_earth_and_its_inhabitants_(1876)_(14578799080).jpg)

In early 1516, the Ottoman Empire, wary of the danger of an alliance between the Mamluks and the Persian Safavids, started a campaign of conquest against the Mamluk sultanate. On 21 September, the Mamluk governor of Damascus fled the city, and on 2 October the khutba in the Umayyad mosque was pronounced in the name of Selim I. The day after, the victorious sultan entered the city, staying for three months. On 15 December, he left Damascus by Bab al-Jabiya, intent on the conquest of Egypt. Little appeared to have changed in the city: one army had simply replaced another. However, on his return in October 1517, the sultan ordered the construction of a mosque, tekkiye and mausoleum at the shrine of Shaikh Muhi al-Din ibn Arabi in al-Salihiyah. This was to be the first of Damascus' great Ottoman monuments. During this time, according to an Ottoman census, Damascus had 10,423 households.[101]

The Ottomans remained for the next 400 years, except for a brief occupation by Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt from 1832 to 1840. Because of its importance as the point of departure for one of the two great Hajj caravans to Mecca, Damascus was treated with more attention by the Porte than its size might have warranted—for most of this period, Aleppo was more populous and commercially more important. In 1559 the western building of Sulaymaniyya Takiyya, comprising a mosque and khan for pilgrims on the road to Mecca, was completed to a design by the famous Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan, and soon afterward the Salimiyya Madrasa was built adjoining it.[102]

Early in the nineteenth century, Damascus was noted for its shady cafes along the banks of the Barada. A depiction of these by William Henry Bartlett was published in 1836, along with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon, see ![]() Cafes in Damascus. Under Ottoman rule, Christians and Jews were considered dhimmis and were allowed to practice their religious precepts. During the Damascus affair of 1840 the false accusation of ritual murder was brought against members of the Jewish community of Damascus. The massacre of Christians in 1860 was also one of the most notorious incidents of these centuries when fighting between Druze and Maronites in Mount Lebanon spilled over into the city. Several thousand Christians were killed in June 1860, with many more being saved through the intervention of the Algerian exile Abd al-Qadir and his soldiers (three days after the massacre started), who brought them to safety in Abd al-Qadir's residence and the Citadel of Damascus. The Christian quarter of the old city (mostly inhabited by Catholics), including several churches, was burnt down. The Christian inhabitants of the notoriously poor and refractory Midan district outside the walls (mostly Orthodox) were, however, protected by their Muslim neighbors.

Cafes in Damascus. Under Ottoman rule, Christians and Jews were considered dhimmis and were allowed to practice their religious precepts. During the Damascus affair of 1840 the false accusation of ritual murder was brought against members of the Jewish community of Damascus. The massacre of Christians in 1860 was also one of the most notorious incidents of these centuries when fighting between Druze and Maronites in Mount Lebanon spilled over into the city. Several thousand Christians were killed in June 1860, with many more being saved through the intervention of the Algerian exile Abd al-Qadir and his soldiers (three days after the massacre started), who brought them to safety in Abd al-Qadir's residence and the Citadel of Damascus. The Christian quarter of the old city (mostly inhabited by Catholics), including several churches, was burnt down. The Christian inhabitants of the notoriously poor and refractory Midan district outside the walls (mostly Orthodox) were, however, protected by their Muslim neighbors.

American Missionary E.C. Miller records that in 1867 the population of the city was 'about' 140,000, of whom 30,000 were Christians, 10,000 Jews, and 100,000 'Mohammedans' with fewer than 100 Protestant Christians.[103] In the meantime, American writer Mark Twain visited Damascus, then wrote about his travel in The Innocents Abroad, in which he mentioned: "Though old as history itself, thou art fresh as the breath of spring, blooming as thine own rose-bud, and fragrant as thine own orange flower, O Damascus, pearl of the East!".[104] In November 1898, German emperor Wilhelm II toured Damascus, during his trip to the Ottoman Empire.[105]

In the early years of the 20th century, nationalist sentiment in Damascus, initially cultural in its interest, began to take a political coloring, largely in reaction to the turkicisation program of the Committee of Union and Progress government established in Istanbul in 1908. The hanging of a number of patriotic intellectuals by Jamal Pasha, governor of Damascus, in Beirut and Damascus in 1915 and 1916 further stoked nationalist feeling, and in 1918, as the forces of the Arab Revolt and the British Imperial forces approached, residents fired on the retreating Turkish troops.

On 1 October 1918, T.E. Lawrence entered Damascus, the third arrival of the day, the first being the Australian 3rd Light Horse Brigade, led by Major A.C.N. 'Harry' Olden.[106] Two days later, 3 October 1918, the forces of the Arab revolt led by Prince Faisal also entered Damascus.[107] A military government under Shukri Pasha was named and Faisal ibn Hussein was proclaimed king of Syria. Political tension arose in November 1917, when the new Bolshevik government in Russia revealed the Sykes-Picot Agreement whereby Britain and France had arranged to partition the Arab East between them. A new Franco-British proclamation on 17 November promised the "complete and definitive freeing of the peoples so long oppressed by the Turks." The Syrian National Congress in March adopted a democratic constitution. However, the Versailles Conference had granted France a mandate over Syria, and in 1920 a French army commanded by the General Mariano Goybet crossed the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, defeated a small Syrian defensive expedition at the Battle of Maysalun and entered Damascus. The French made Damascus the capital of their League of Nations Mandate for Syria.

When in 1925 the Great Syrian Revolt in the Hauran spread to Damascus, the French suppressed it with heavy weaponry, bombing and shelling the city on 9 May 1926. As a result, the area of the old city between Al-Hamidiyah Souq and Medhat Pasha Souq was burned to the ground, with many deaths, and has since then been known as al-Hariqa ("the fire"). The old city was surrounded with barbed wire to prevent rebels from infiltrating the Ghouta, and a new road was built outside the northern ramparts to facilitate the movement of armored cars.

On 21 June 1941, 3 weeks into the Allied Syria-Lebanon campaign, Damascus was captured from the Vichy French forces by a mixed British Indian and Free French force. The French agreed to withdraw in 1946, following the British intervention during the Levant Crisis, thus leading to the full independence of Syria. Damascus remained the capital.

In 1979, the Old City of Damascus, with its collection of archaeological and historical religious sites, was listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

By January 2012, clashes between the regular army and rebels reached the outskirts of Damascus, reportedly preventing people from leaving or reaching their houses, especially when security operations there intensified from the end of January into February.[108]

By June 2012, bullets and shrapnel shells smashed into homes in Damascus overnight as troops battled the Free Syrian Army in the streets. At least three tank shells slammed into residential areas in the central Damascus neighborhood of Qaboun, according to activists. Intense exchanges of assault rifle fire marked the clash, according to residents and amateur video posted online.[109]

The Damascus suburb of Ghouta suffered heavy bombing in December 2017 and a further wave of bombing started in February 2018, also known as Rif Dimashq Offensive.

On 20 May 2018, Damascus and the entire Rif Dimashq Governorate came fully under government control for the first time in 7 years after the evacuation of IS from Yarmouk Camp.[110] In September 2019, Damascus entered the Guinness World Records as the least liveable city, scoring 30.7 points on the Economist's Global Liveability Index in 2019, based on factors such as: stability, healthcare, culture and environment, education, and infrastructure.[111] However, the trend of being the least liveable city on Earth started in 2017,[112] and continued as of 2023.[113]

The historical role that Damascus played as an important trade center has changed in recent years due to political development in the region as well as the development of modern trade.[2] Most goods produced in Damascus, as well as in Syria, are distributed to countries of the Arabian peninsula.[2] Damascus has also held an annual international trade exposition every fall, since 1954.[114]

The tourism industry in Damascus has a lot of potential, however, the civil war has hampered these prospects. The abundance of cultural wealth in Damascus has been modestly employed since the late 1980s with the development of many accommodation and transportation establishments and other related investments.[2] Since the early 2000s, numerous boutique hotels and bustling cafes opened in the old city which attracts plenty of European tourists and Damascenes alike.[115]

In 2009 new office space was built and became available on the real estate market.[116] Marota City and Basilia City are two new development projects in Damascus.[117] These two projects are viewed as post-war reconstruction efforts. The Damascus stock exchange formally opened for trade in March 2009, and the exchange is the only stock exchange in Syria.[118] It is located in the Barzeh district, within Syria's financial markets and securities commission. Its final home is to be located in the upmarket business district of Yaafur.[119]

Damascus is home to a wide range of industrial activities, such as textile, food processing, cement, and various chemical industries.[2] The majority of factories are run by the state, however limited privatization in addition to economic activities led by the private sector, were permitted starting in the early 2000s with the liberalization of trade that took place.[2]Traditional handcrafts and artisan copper engravings are still produced in the old city.[2]

_2.006_SZENE_IN_THE_BAZAR.jpg/440px-ADDISON(1838)_2.006_SZENE_IN_THE_BAZAR.jpg)

Damascus's population in 2004 was estimated to be 2.7 million people.[120] The estimated population of Damascus in 2011 was 1,711,000. However, in 2022, the city had an estimated population of 2,503,000, which in early 2023 rose to 2,584,771.[121]

Damascus is the center of a crowded metropolitan area with an estimated population of 5 million. The metropolitan area of Damascus includes the cities of Douma, Harasta, Darayya, Al-Tall and Jaramana.

The city's growth rate is higher than in Syria as a whole, primarily due to rural-urban migration and the influx of young Syrian migrants drawn by employment and educational opportunities.[122] The migration of Syrian youths to Damascus has resulted in an average age within the city that is below the national average.[122] Nonetheless, the population of Damascus is thought to have decreased in recent years as a result of the ongoing Syrian civil war.

The vast majority of Damascenes are Syrian Arabs. The Kurds are the second largest ethnic minority, with a population of approximately 300,000.[123][better source needed] They reside primarily in the neighborhoods of Wadi al-Mashari ("Zorava" or "Zore Afa" in Kurdish) and Rukn al-Din.[124][125] Other minorities include Palestinians, Assyrians, Syrian Turkmen, Armenians, Circassians and a small Greek community.

There was once a significant Jewish community in Damascus, but as of 2023, no Jews remain.[126]

Religion in Damascus (2024)

Islam is the largest religion. The majority of Muslims are Sunni while Alawites and Twelver Shi'a comprise sizeable minorities. Alawites live primarily in the Mezzeh districts of Mezzeh 86 and Sumariyah. Twelvers primarily live near the Shia holy sites of Sayyidah Ruqayya and Sayyidah Zaynab. It is believed that there are more than 200 mosques in Damascus, the most well-known being the Umayyad Mosque.[127]

Christians represent about 10%–15% of the population.[citation needed] Several Eastern Christian rites have their headquarters in Damascus, including the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, and the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch. The Christian districts in the city are Bab Tuma, Qassaa and Ghassani. Each have many churches, most notably the ancient Chapel of Saint Paul and St Georges Cathedral in Bab Tuma. At the suburb of Soufanieh a series of apparitions of the Virgin Mary have reportedly been observed between 1982 and 2004.[128] The Patriarchal See of the Syriac Orthodox is based in Damascus, Bab Touma.

A smaller Druze minority inhabits the city, notably in the mixed Christian-Druze suburbs of Tadamon,[129] Jaramana,[130] and Sahnaya.

There was a small Jewish community namely in what is called Harat al-Yahud the Jewish quarter. They are the remnants of an ancient and much larger Jewish presence in Syria, dating back at least to Roman times, if not before to the time of King David.[131]

Sufism throughout the second half of the 20th century has been an influential current in the Sunni religious practises, particularly in Damascus. The largest women-only and girls-only Muslim movement in the world happens to be Sufi-oriented and is based in Damascus, led by Munira al-Qubaysi. Syrian Sufism has its stronghold in urban regions such as Damascus, where it also established political movements such as Zayd, with the help of a series of mosques, and clergy such as Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi, Sa'id Hawwa, Abd al-Rahman al-Shaghouri and Muhammad al-Yaqoubi.[132]

Damascus has a wealth of historical sites dating back to many different periods of the city's history. Since the city has been built up with every passing occupation, it has become almost impossible to excavate all the ruins of Damascus that lie up to 2.4 m (8 ft) below the modern level. [citation needed] The Citadel of Damascus is in the northwest corner of the Old City. The Damascus Straight Street (referred to in the account of the conversion of St. Paul in Acts 9:11), also known as the Via Recta, was the decumanus (east-west main street) of Roman Damascus, and extended for over 1,500 m (4,900 ft). Today, it consists of the street of Bab Sharqi and the Souk Medhat Pasha, a covered market. The Bab Sharqi street is filled with small shops and leads to the old Christian quarter of Bab Tuma (St. Thomas's Gate), where St George's Cathedral, the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Church, is notably located. Medhat Pasha Souq is also a main market in Damascus and was named after Midhat Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Syria who renovated the Souk. At the end of Bab Sharqi Street, one reaches the House of Ananias, an underground chapel that was the cellar of Ananias's house. The Umayyad Mosque, also known as the Grand Mosque of Damascus, is one of the largest mosques in the world and also one of the oldest sites of continuous prayer since the rise of Islam. A shrine in the mosque is said to contain the body of St. John the Baptist. The mausoleum where Saladin was buried is located in the gardens just outside the mosque. Sayyidah Ruqayya Mosque, the shrine of the youngest daughter of Husayn ibn Ali, can also be found near the Umayyad Mosque. The ancient district of Amara is also within walking distance from these sites. Another heavily visited site is Sayyidah Zaynab Mosque, where the tomb of Zaynab bint Ali is located.

Shias, Fatemids, and Dawoodi Bohras believe that after the battle of Karbala (680 AD), in Iraq, the Umayyad Caliph Yezid brought Imam Husain's head to Damascus, where it was first kept in the courtyard of Yezid Mahal, now part of Umayyad Mosque complex. All other remaining members of Imam Husain's family (left alive after Karbala) along with the heads of all other companions, who were killed at Karbala, were also brought to Damascus. These members were kept as prisoners on the outskirts of the city (near Bab al-Saghir), where the other heads were kept at the same location, now called Ru'ûs ash-Shuhadâ-e-Karbala or ganj-e-sarha-e-shuhada-e-Karbala.[133] There is a qibla (place of worship) marked at the place, where devotees say Imam Ali-Zain-ul-Abedin used to pray while in captivity.[citation needed]

The Harat Al Yehud[134] or Jewish Quarter is a recently restored historical tourist destination popular among Europeans before the outbreak of civil war.[citation needed]

The Old City of Damascus with an approximate area of 86.12 hectares[135] is surrounded by ramparts on the northern and eastern sides and part of the southern side. There are seven extant city gates, the oldest of which dates back to the Roman period. These are, clockwise from the north of the citadel:

Other areas outside the walled city also bear the name "gate": Bab al-Faraj, Bab Mousalla and Bab Sreija, both to the south-west of the walled city.

Due to the rapid decline of the population of Old Damascus (between 1995 and 2009 about 30,000 people moved out of the old city for more modern accommodation),[137] a growing number of buildings are being abandoned or are falling into disrepair. In March 2007, the local government announced that it would be demolishing Old City buildings along a 1,400 m (4,600 ft) stretch of rampart walls as part of a redevelopment scheme. These factors resulted in the Old City being placed by the World Monuments Fund on its 2008 Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites in the world.[138][139] It is hoped that its inclusion on the list will draw more public awareness to these significant threats to the future of the historic Old City of Damascus.

In spite of the recommendations of the UNESCO World Heritage Center:[140]

In October 2010, Global Heritage Fund named Damascus one of 12 cultural heritage sites most "on the verge" of irreparable loss and destruction.[142]

Damascus is the main center of education in Syria. It is home to Damascus University, which is the oldest and largest university in Syria. After the enactment of legislation allowing private higher institutions, several new universities were established in the city and the surrounding area, including:

The institutes play an important rule in the education, including:

In Damascus, Higher education in Syrian Arab Republic started with sustainable development steps through Damascus University. [145]

Damascus is linked with other major cities in Syria via a motorway network. The M5 connects Damascus with Homs, Hama, Aleppo and Turkey in the north and Jordan in the south. The M1 is going from Homs onto Latakia and Tartus. The M4 links the city with Al-Hasakah and Iraq. The M1 highway connects the city to western Syria and Beirut.

The main airport is Damascus International Airport, approximately 20 km (12 mi) away from the city, with connections to a few Middle Eastern cities. Before the beginning of the Syrian civil war, the airport had connectivity to many Asian, European, African, and, South American cities.

Streets in Damascus are often narrow, especially in the older parts of the city, and speed bumps are widely used to limit the speed of vehicles. Many taxi companies operate in Damascus. Fares are regulated by law and taxi drivers are obliged to use a taximeter.

Public transport in Damascus depends extensively on buses and minibuses. There are about one hundred lines that operate inside the city and some of them extend from the city center to nearby suburbs. There is no schedule for the lines, and due to the limited number of official bus stops, buses will usually stop wherever a passenger needs to get on or off. The number of buses serving the same line is relatively high, which minimizes the waiting time. Lines are not numbered, rather they are given captions mostly indicating the two endpoints and possibly an important station along the line. Between 2019 and 2022, more than 100 modern buses were delivered from China as part of the international agreement. These deliveries strengthened and modernized the public transport of Damascus.[146][147]

Served by Chemins de Fer Syriens, the former main railway station of Damascus was al-Hejaz railway station, about 1 km (5⁄8 mi) west of the old city. The station is now defunct and the tracks have been removed, but there still is a ticket counter and a shuttle to Damascus Qadam station in the south of the city, which now functions as the main railway station.

In 2008, the government announced a plan to construct a Damascus Metro.[148] The green line will be an essential west–east axis for the future public transportation network, serving Moadamiyeh, Sumariyeh, Mezzeh, Damascus University, Hijaz, the Old City, Abbassiyeen and Qaboun Pullman bus station. A four-line metro network is expected to be in operation by 2050.

Damascus was chosen as the 2008 Arab Capital of Culture.[149] The preparation for the festivity began in February 2007 with the establishing of the Administrative Committee for "Damascus Arab Capital of Culture" by a presidential decree.[150] Museums in Damascus includes National Museum of Damascus, Azem Palace, Military Museum, October War Panorama Museum, Museum of Arabic Calligraphy and Nur al-Din Bimaristan

Popular sports include football, basketball, swimming, tennis, table tennis, equestrian and chess. Damascus is home to many football clubs that participate in the Syrian Premier League including al-Jaish, al-Shorta, Al-Wahda and Al-Majd. Many Other sports clubs are located in several districts of the city: Barada SC, Al-Nidal SC, Al-Muhafaza, Qasioun SC, al-Thawra SC, Maysalun SC, al-Fayhaa SC, Dummar SC, al-Majd SC and al-Arin SC.

The fifth and the seventh Pan Arab Games were held in Damascus in 1976 and 1992 respectively.

The now modernized Al-Fayhaa Sports City features a basketball court and a hall that can accommodate up to 8,000 people. In late November 2021, Syria's national basketball team played there against Kazakhstan, making Damascus host of Syria's first international basketball tournament in almost two decades.[151]

The city also has a modern golf course located near the Ebla Cham Palace Hotel on the southeastern outskirts of Damascus.

Damascus has a busy nightlife. Coffeehouses offer Arabic coffee, tea and nargileh (water pipes). Card games, tables (backgammon variants), and chess are activities frequented in cafés.[152] These coffeehouses had an international reputation in the past, as indicated by Letitia Elizabeth Landon's poetical illustration, Cafes in Damascus, to a picture by William Henry Bartlett in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1837.[153] Current movies can be seen at Cinema City which was previously known as Cinema Dimashq.

Tishreen Park is one of the largest parks in Damascus. It is home to the annual Damascus Flower Show. Other parks include al-Jahiz, al-Sibbki, al-Tijara, al-Wahda, etc... The city's famous Ghouta oasis is also a weekend destination for recreation. Many recreation centers operate in the city including sports clubs, swimming pools, and golf courses. The Syrian Arab Horse Association in Damascus offers a wide range of activities and services for horse breeders and riders.[154]

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2024 (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)