Повешение — это убийство человека путем подвешивания его за шею с помощью петли или лигатуры . Повешение было распространенным методом смертной казни со времен Средневековья и является основным методом казни во многих странах и регионах. Первое известное упоминание о казни через повешение содержится в « Одиссее » Гомера . [1] Повешение также является методом самоубийства .

Прошедшее время и причастие прошедшего времени глагола hang в этом смысле — hanged , а не hung .

Существует множество методов повешения при исполнении смертного приговора, которые приводят к смерти либо от перелома шейных позвонков , либо от удушения .

.jpg/440px-Biskupia_Gorka_executions_-_14_-_Barkmann,_Paradies,_Becker,_Klaff,_Steinhoff_(left_to_right).jpg)

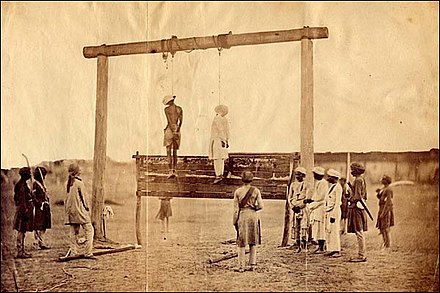

Короткое падение — это метод повешения, при котором осужденный стоит на возвышении, например, на табурете, лестнице, тележке или другом транспортном средстве, с петлей на шее. Затем опору убирают, оставляя человека висеть на веревке. [2] [3]

Подвешенный за шею, вес тела затягивает петлю вокруг шеи, вызывая удушение и смерть. Потеря сознания обычно происходит быстро, и смерть наступает через несколько минут. [4]

До 1850 года стандартным методом повешения был метод короткого падения, который до сих пор широко применяется при самоубийствах и внесудебных казнях (таких как линчевание и суммарные казни ), для которых не используются специализированное оборудование и таблицы расчета длины падения, используемые в новых методах.

Вариантом короткого падения является австро-венгерский метод «столба», называемый Würgegalgen (дословно: удушающая виселица), при котором выполняются следующие шаги:

Этот метод позднее был принят и государствами-правопреемниками, в частности Чехословакией , где метод «столба» использовался как единственный тип казни с 1918 года до отмены смертной казни в 1990 году. Нацистский военный преступник Карл Герман Франк , казненный в 1946 году в Праге , был среди примерно 1000 приговоренных, казненных таким образом в Чехословакии. [5]

Стандартное падение подразумевает падение с высоты от 4 до 6 футов (1,2–1,8 м) и вошло в употребление с 1866 года, когда научные подробности были опубликованы ирландским врачом Сэмюэлем Хоутоном . Его использование быстро распространилось в англоязычных странах и странах с судебными системами английского происхождения.

Это считалось гуманным улучшением по сравнению с коротким падением, поскольку предполагалось, что этого будет достаточно, чтобы сломать шею человека , вызывая немедленную потерю сознания и быструю смерть мозга. [6] [7]

Этот метод использовался для казни осужденных нацистов под юрисдикцией Соединенных Штатов после Нюрнбергского процесса , включая Иоахима фон Риббентропа и Эрнста Кальтенбруннера . [8] [ недостаточно конкретно для проверки ] Во время казни Риббентропа историк Джайлс Макдонох отмечает, что: «Палач не справился с казнью, и веревка душила бывшего министра иностранных дел в течение 20 минут, прежде чем он скончался». [9] В отчете журнала Life о казни просто говорится: «Ловушка открылась, и со звуком, средним между грохотом и треском, Риббентроп исчез. Веревка некоторое время дрожала, затем выпрямилась и натянулась». [10]

Процесс длинного падения, также известный как измеренное падение, был представлен в Британии в 1872 году Уильямом Марвудом как научный прогресс по сравнению со стандартным падением и далее усовершенствован его преемником Джеймсом Берри . Вместо того, чтобы все падали с одинаковой стандартной высоты, рост и вес человека [11] использовались для определения того, насколько слабину будет предоставлена веревке, чтобы расстояние падения было достаточным для того, чтобы гарантировать, что шея будет сломана, но не настолько, чтобы человек был обезглавлен. Осторожное размещение проушины или узла петли (так, чтобы голова была отдернута назад, когда веревка затягивалась) способствовало перелому шеи.

До 1892 года падение составляло от 4 до 10 футов (от 1,2 до 3,0 м) в зависимости от веса тела и было рассчитано на передачу энергии в 1260 футо-фунтов силы (1710 Дж ), что приводило к перелому шеи либо на уровне 2-го и 3-го, либо на уровне 4-го и 5-го шейных позвонков . Эта сила привела к некоторым обезглавливаниям, таким как печально известный случай с Блэк Джеком Кетчумом на территории Нью-Мексико в 1901 году из-за того, что значительное увеличение веса во время содержания под стражей не было учтено в расчетах падения. Между 1892 и 1913 годами длина падения была сокращена, чтобы избежать обезглавливания. После 1913 года были приняты во внимание и другие факторы, и передаваемая энергия была уменьшена примерно до 1000 футо-фунтов силы (1400 Дж).

Обезглавливание Евы Дуган во время неудачного повешения в 1930 году привело к тому, что штат Аризона перешел на газовую камеру в качестве основного метода казни, поскольку считалось, что это более гуманно. [13] Одно из последних обезглавливаний в результате длительного падения произошло, когда Барзан Ибрагим аль-Тикрити был повешен в Ираке в 2007 году. [14] Случайное обезглавливание также произошло во время повешения Артура Лукаса в 1962 году , одного из последних двух людей, казненных в Канаде. [15]

Нацисты, казненные под британской юрисдикцией, включая Йозефа Крамера , Фрица Кляйна , Ирму Грезе и Элизабет Фолькенрат , были повешены Альбертом Пирпойнтом с использованием метода переменного падения, разработанного Марвудом. Рекордная скорость для британского повешения с длинным падением составила семь секунд с момента входа палача в камеру до падения. Скорость считалась важной в британской системе, поскольку она уменьшала душевные страдания осужденного. [16]

Длинное повешение до сих пор практикуется как метод казни в некоторых странах, включая Японию и Сингапур. [17] [18]

Повешение является распространенным методом самоубийства . Материалы, необходимые для самоубийства через повешение, легко доступны для обычного человека, по сравнению с огнестрельным оружием или ядами. Полное подвешивание не требуется, и по этой причине повешение особенно распространено среди заключенных, склонных к самоубийству . Тип повешения, сравнимый с полным подвешиванием, может быть получен путем самоудушения с использованием лигатуры вокруг шеи и частичного веса тела (частичное подвешивание) для затягивания лигатуры. Когда самоубийственное повешение включает частичное подвешивание, обнаруживается, что обе ноги умершего касаются земли, например, он стоит на коленях, приседает или стоит. Иногда используется частичное подвешивание или частичная нагрузка на лигатуру, особенно в тюрьмах, психиатрических больницах или других учреждениях, где трудно разработать полную поддержку подвешивания, потому что высокие точки лигатуры (например, крючки или трубы) были удалены. [19]

В Канаде повешение является наиболее распространенным методом самоубийства, [20] а в США повешение является вторым по распространенности методом после нанесения себе огнестрельных ранений . [21] В Соединенном Королевстве, где огнестрельное оружие менее доступно, в 2001 году повешение было наиболее распространенным методом среди мужчин и вторым по распространенности среди женщин (после отравления). [22]

Те, кто выжил после попытки самоубийства через повешение, будь то из-за разрыва веревки или точки лигатуры , или из-за того, что их обнаружили и зарезали, сталкиваются с рядом серьезных травм, включая церебральную аноксию (которая может привести к необратимому повреждению мозга), перелом гортани, перелом шейного отдела позвоночника (который может вызвать паралич ), перелом трахеи, разрыв глотки и повреждение сонной артерии. [23]

Есть некоторые предположения , что викинги практиковали повешение в качестве человеческих жертвоприношений Одину , чтобы почтить жертву Одина, повесившегося на Иггдрасиле . [24] В Северной Европе широко распространено мнение, что болотные тела железного века , многие из которых имеют следы повешения, были примерами человеческих жертвоприношений богам. [25]

Повешение может вызвать одно или несколько из следующих заболеваний, некоторые из которых приводят к смерти:

Причина смерти при повешении зависит от условий, связанных с событием. Когда тело освобождается из относительно высокого положения, основной причиной смерти является тяжелая травма верхнего шейного отдела позвоночника. Полученные травмы сильно различаются. Одно исследование показало, что только небольшое меньшинство из серии судебных повешений приводило к переломам шейного отдела позвоночника (6 из 34 изученных случаев), причем половина этих переломов (3 из 34) представляла собой классический « перелом палача » (двусторонние переломы межсуставной части позвонка С2). [26] Расположение узла на веревке для повешения является основным фактором, определяющим механику травмы шейного отдела позвоночника, при этом подбородочный узел (узел палача под подбородком) является единственным местом, способным вызвать внезапную, прямую травму от гиперэкстензии, которая вызывает классический «перелом палача».

Согласно Историческим и биомеханическим аспектам перелома палача , фраза в обычном приказе о казни «повешен за шею до наступления смерти» была необходима. [1] К концу 19 века это методическое исследование позволило властям регулярно применять повешение способами, которые предсказуемо быстро убивали жертву.

Было показано, что боковой или подушной узел может вызывать другие, более сложные травмы, при этом в одном тщательно изученном случае были получены только повреждения связок шейного отдела позвоночника и двусторонние разрывы позвоночных артерий, но не было серьезных переломов позвонков или раздавливающих повреждений спинного мозга. [27] Смерть от «перелома палача» наступает в основном тогда, когда приложенная сила достаточно сильна, чтобы также вызвать серьезный подвывих позвонков C2 и C3, который раздавливает спинной мозг и/или разрывает позвоночные артерии. Переломы палача от других травм гиперэкстензии (наиболее распространенными являются аварии с участием неудерживаемых транспортных средств и падения или травмы при нырянии, когда лицо или подбородок внезапно ударяются о неподвижный объект) часто выживают, если приложенная сила не вызывает серьезного подвывиха C2 на C3.

При отсутствии перелома и вывиха основной причиной смерти становится окклюзия кровеносных сосудов, а не асфиксия . Затруднение венозного оттока мозга через окклюзию внутренних яремных вен приводит к отеку мозга , а затем к церебральной ишемии . Лицо обычно становится набухшим и цианотичным (синеет из-за недостатка кислорода). Нарушение мозгового кровотока может произойти из-за закупорки сонных артерий, хотя их закупорка требует гораздо большей силы, чем закупорка яремных вен, поскольку они расположены глубже и содержат кровь под гораздо более высоким давлением по сравнению с яремными венами. [28]

Когда мозговое кровообращение серьезно нарушено любым механизмом, артериальным или венозным, смерть наступает в течение четырех или более минут от церебральной гипоксии, хотя сердце может продолжать биться в течение некоторого периода после того, как мозг больше не может быть реанимирован. Время смерти в таких случаях является вопросом соглашения. В судебных повешениях смерть объявляется при остановке сердца, которая может наступить порой от нескольких минут до 15 минут или дольше после повешения. [ необходима цитата ]

Сфинктеры расслабятся спонтанно, и моча и фекалии будут эвакуированы. Судебные эксперты часто могут сказать, является ли повешение самоубийством или убийством, поскольку каждое оставляет характерный след от лигатуры. Одним из намеков, которые они используют, является подъязычная кость . Если она сломана, это часто означает, что человек был убит путем удушения вручную . [ требуется цитата ]

Повешение было методом смертной казни во многих странах и до сих пор используется многими странами. Длинное повешение в основном используется бывшими британскими колониями, в то время как короткое повешение и подвешивание распространены в других странах, включая Иран и Афганистан.

Повешение является наиболее используемой формой смертной казни в Афганистане . [ необходима ссылка ]

Смертная казнь была частью правовой системы Австралии с момента создания Нового Южного Уэльса как британской исправительной колонии до 1985 года, когда все австралийские штаты и территории отменили смертную казнь; [29] на практике последней казнью в Австралии было повешение Рональда Райана 3 февраля 1967 года в Виктории . [30]

В 19 веке преступления, которые могли караться смертной казнью, включали в себя кражу со взломом , кражу овец, подделку документов , сексуальные нападения , преднамеренные убийства и непредумышленные убийства . В 19 веке в австралийских колониях за эти преступления ежегодно вешали около восьмидесяти человек. [ необходима цитата ]

На Багамах для казни осужденных применяется повешение, однако с 2000 года в стране не проводилось ни одной казни. В последние годы некоторые заключенные находились в камерах смертников, но их приговоры были смягчены. [31]

Повешение является единственным методом казни в Бангладеш с момента обретения страной независимости.

Смертная казнь через повешение была обычным методом смертной казни в Бразилии на протяжении всей ее истории. Некоторые важные национальные герои, такие как Тирадентис (1792), были казнены через повешение. Последним человеком, казненным в Бразилии, был раб Франсиско в 1876 году. [32] Смертная казнь была отменена за все преступления, за исключением тех, которые были совершены при чрезвычайных обстоятельствах, таких как война или военное положение, в 1890 году. [33]

Национальный герой Болгарии Васил Левски был казнен через повешение Османским судом в Софии в 1873 году. Каждый год после освобождения Болгарии тысячи людей приходят с цветами в день его смерти, 19 февраля, к его памятнику, где стояла виселица. Последняя казнь была в 1989 году, а смертная казнь была отменена за все преступления в 1998 году. [33]

Исторически повешение было единственным методом казни, используемым в Канаде, и использовалось в качестве возможного наказания за все убийства до 1961 года, когда убийства были переклассифицированы в преступления, караемые смертной казнью, и преступления, не караемые смертной казнью. Смертная казнь была ограничена для применения только за определенные преступления в соответствии с Законом о национальной обороне в 1976 году и была полностью отменена в 1998 году. [34] Последние повешения в Канаде состоялись 11 декабря 1962 года. [33]

В 1955 году в Египте повесили трех израильтян по обвинению в шпионаже. [35] В 1982 году в Египте повесили трех гражданских лиц, осужденных за убийство Анвара Садата . [36] В 2004 году в Египте повесили пять боевиков по обвинению в попытке убийства премьер-министра. [37] По сей день повешение остается стандартным методом смертной казни в Египте, где ежегодно казнят больше людей, чем в любой другой африканской стране.

На территориях, оккупированных нацистской Германией с 1939 по 1945 год, удушение через повешение было предпочтительным способом публичной казни, хотя больше уголовных казней проводилось с помощью гильотины , чем через повешение. Чаще всего приговаривали партизан и спекулянтов , чьи тела обычно оставляли висеть в течение длительного времени. Также имеются многочисленные сообщения о повешении заключенных концлагерей. Повешение продолжалось в послевоенной Германии в британских и американских оккупационных зонах, находящихся под их юрисдикцией, а также для нацистских военных преступников, до тех пор, пока сама (западная) Германия не отменила смертную казнь немецкой конституцией , принятой в 1949 году. Западный Берлин не подпадал под действие Grundgesetz ( Основного закона ) и отменил смертную казнь в 1951 году. Германская Демократическая Республика отменила смертную казнь в 1987 году. Последняя казнь, назначенная западногерманским судом, была проведена с помощью гильотины в тюрьме Моабит в 1949 году. Последнее повешение в Германии было назначено нескольким военным преступникам в Ландсберге-на-Лехе 7 июня 1951 года. Последняя известная казнь в Восточной Германии была в 1981 году выстрелом из пистолета в шею. [29]

Несмотря на то, что Гонконг сейчас является частью Китая, в нем нет смертной казни; это особый административный район Китая. Когда Гонконг еще был частью Британской империи, там применялось повешение как метод казни. Последним казненным человеком был китаец-вьетнамец, который напал на охранника и еще одного человека. Это было в 1966 году. [38]

Премьер-министр Венгрии во время Революции 1956 года Имре Надь был тайно судим, казнен через повешение и бесцеремонно похоронен новым венгерским правительством, поддерживаемым Советским Союзом , в 1958 году. Позднее Надь был публично оправдан Венгрией. [39] Смертная казнь была отменена за все преступления в 1990 году. [29]

Повешение было введено британцами. Все казни в Индии с момента обретения независимости проводились через повешение, хотя закон предусматривает, что военные казни должны проводиться через расстрел. В 1949 году Натхурам Годзе , приговоренный к смертной казни за убийство Махатмы Ганди , стал первым человеком, казненным через повешение в независимой Индии. [40]

Верховный суд Индии предположил, что смертная казнь должна применяться только в «редчайших из редких случаев». [41]

С 2001 года в Индии были казнены восемь человек. Дхананджой Чаттерджи , насильник и убийца 1991 года, был казнен 14 августа 2004 года в тюрьме Алипор , Калькутта. Аджмал Касаб , единственный выживший террорист терактов в Мумбаи 2008 года, был казнен 21 ноября 2012 года в тюрьме Йервада-Сентрал , Пуна. Верховный суд Индии ранее отклонил его прошение о помиловании, которое затем было отклонено президентом Индии. Он был повешен неделю спустя. Афзал Гуру , террорист, признанный виновным в заговоре в декабре 2001 года в нападении на индийский парламент , был казнен через повешение в тюрьме Тихар , Дели 9 февраля 2013 года. Якуб Мемон был осужден за участие в взрывах в Бомбее в 1993 году Специальным судом по делам о терроризме и подрывной деятельности 27 июля 2007 года. Все его апелляции и прошения о помиловании были отклонены, и он был наконец казнен через повешение 30 июля 2015 года в тюрьме Нагпура. В марте 2020 года четверо заключенных, осужденных за изнасилование и убийство, были казнены через повешение в тюрьме Тихар. [42]

.jpg/440px-Public_execution_for_a_convicted_of_rape_in_Qarchak,_Varamin_-_26_October_2011_(13900804092511).jpg)

Смерть через повешение является основным средством смертной казни в Иране, где ежегодно проводится одно из самых высоких в мире число казней. Используемый метод — короткое падение, при котором шея осужденного не ломается, а скорее наступает более медленная смерть из-за удушения. Это законно для убийств, изнасилований и торговли наркотиками, если только преступник не заплатит дийю семье жертвы, таким образом получив ее прощение (см. Шариат ). Если председательствующий судья сочтет дело «вызывающим общественное возмущение», он может приказать, чтобы повешение произошло публично на месте совершения преступления, как правило, с помощью мобильного телескопического крана, который поднимает осужденного высоко в воздух. [43] 19 июля 2005 года двое мальчиков, Махмуд Асгари и Аяз Мархони , в возрасте 15 и 17 лет соответственно, которые были осуждены за изнасилование 13-летнего мальчика, были повешены на площади Эдалат (Справедливость) в Мешхеде по обвинению в гомосексуализме и изнасиловании . [44] [45] 15 августа 2004 года 16-летняя девушка, Атефех Сахаалех (также известная как Атефех Раджаби), была казнена за совершение «действий, несовместимых с целомудрием ». [46]

На рассвете 27 июля 2008 года иранское правительство казнило 29 человек в тюрьме Эвин в Тегеране. [47] 2 декабря 2008 года неназванный мужчина был повешен за убийство в тюрьме Казероун, всего через несколько минут после того, как его помиловала семья убитого. Его быстро срезали и доставили в больницу, где его успешно реанимировали. [48]

Осуждение и повешение Рейхане Джаббари вызвали международный резонанс, поскольку она была приговорена к смертной казни в 2009 году и повешена 25 октября 2014 года за убийство бывшего сотрудника разведки; согласно показаниям Джаббари, она нанесла ему ножевое ранение во время попытки изнасилования, а затем другой человек убил его. [49]

Повешение использовалось при режиме Саддама Хусейна , [50] но было приостановлено вместе со смертной казнью 10 июня 2003 года, когда коалиция во главе с Соединенными Штатами вторглась и свергла предыдущий режим. Смертная казнь была восстановлена 8 августа 2004 года. [51]

В сентябре 2005 года трое убийц стали первыми людьми, казненными после реставрации. Затем, 9 марта 2006 года, чиновник Верховного судебного совета Ирака подтвердил, что иракские власти казнили первых повстанцев через повешение. [52]

Саддам Хусейн был приговорен к смертной казни через повешение за преступления против человечности [53] 5 ноября 2006 года и был казнен 30 декабря 2006 года примерно в 6:00 утра по местному времени. Во время падения раздался слышимый треск, указывающий на то, что его шея была сломана, что является успешным примером повешения с длинным падением. [54]

Барзан Ибрагим , глава Мухабарата, агентства безопасности Саддама, и Авад Хамед аль-Бандар , бывший главный судья, были казнены 15 января 2007 года также методом длинного падения, но Барзан был обезглавлен веревкой в конце своего падения. [55]

Бывший вице-президент Таха Яссин Рамадан был приговорен к пожизненному заключению 5 ноября 2006 года, но приговор был изменен на смертную казнь через повешение 12 февраля 2007 года. [56] Он был четвертым и последним человеком, казненным за преступления против человечности 1982 года 20 марта 2007 года. Казнь прошла гладко. [57]

На суде по делу о геноциде в Анфале двоюродный брат Саддама Али Хасан аль-Маджид ( псевдоним Химик Али), бывший министр обороны Султан Хашим Ахмед аль-Тай и бывший заместитель Хусейн Рашид Мохаммед были приговорены к повешению за их роль в кампании Аль-Анфал против курдов 24 июня 2007 года. [58] Аль-Маджид был приговорен к смертной казни еще три раза: один раз за подавление шиитского восстания в 1991 году вместе с Абдул-Гани Абдул Гафуром 2 декабря 2008 года; [59] один раз за подавление убийства великого аятоллы Мухаммеда ас-Садра в 1999 году 2 марта 2009 года; [60] и один раз 17 января 2010 года за отравление курдов газом в 1988 году; [61] он был повешен 25 января. [62]

26 октября 2010 года главный министр Саддама Тарик Азиз был приговорен к повешению за преследование членов конкурирующих шиитских политических партий. [63] Его приговор был заменен бессрочным тюремным заключением после того, как президент Ирака Джаляль Талабани не подписал приказ о его казни, и он умер в тюрьме в 2015 году.

14 июля 2011 года американские войска передали осужденных заключенных Султана Хашима Ахмеда аль-Тая и двух единокровных братьев Саддама, Сабави Ибрагима аль-Тикрити и Ватбана Ибрагима аль-Тикрити , иракским властям для казни. [64] Верховный трибунал Ирака приговорил единокровных братьев Саддама к смертной казни 11 марта 2009 года за их роль в казнях 42 торговцев, обвинявшихся в манипулировании ценами на продукты питания . [65] Ни один из троих мужчин не был казнен.

Утверждается, что правительство Ирака держит в секрете количество казней, и сотни из них могут быть казнены каждый год. В 2007 году Amnesty International заявила, что 900 человек находятся под «неминуемым риском» казни в Ираке.

Хотя в уголовном праве Израиля есть положения, позволяющие применять смертную казнь за чрезвычайные преступления, она применялась только дважды, и только одна из этих казней была через повешение. 31 мая 1962 года нацистский лидер Адольф Эйхман был схвачен, доставлен в Израиль, а затем казнен через повешение. [33]

Все казни в Японии осуществляются через повешение.

On 23 December 1948, Hideki Tojo, Kenji Doihara, Akira Mutō, Iwane Matsui, Seishirō Itagaki, Kōki Hirota, and Heitaro Kimura were hanged at Sugamo Prison by the U.S. occupation authorities in Ikebukuro in Allied-occupied Japan for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against peace during the Asian-Pacific theatre of World War II.[66][67]

On 27 February 2004, the mastermind of the Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, Shoko Asahara, was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. On 25 December 2006, serial killer Hiroaki Hidaka and three others were hanged in Japan. Long-drop hanging is the method of carrying out judicial capital punishment on civilians in Japan, as in the cases of Norio Nagayama,[68] Mamoru Takuma,[69] and Tsutomu Miyazaki.[70] In 2018 Shoko Asahara and several of his cult members were hanged for committing the 1995 sarin gas attack.

Death by hanging is the traditional method of capital punishment in Jordan. On 14 August 1993, Jordan hanged two Jordanians convicted of spying for Israel.[71] Sajida al-Rishawi, "The 4th bomber" of the 2005 Amman bombings, was executed by hanging alongside Ziad al-Karbouly on 4 February 2015 in retribution for the immolation of Jordanian pilot Muath Al-Kasasbeh.

Kuwait has always used hanging for execution. During the Gulf War, Iraqi government officials executed different people for different reasons. After the war, Kuwait hanged Iraqi collaborators.[72] Sometimes the executions are in public. The most recent executions were in 2022.[73]

Lebanon hanged two men in 1998 for murdering a man and his sister.[74] However, capital punishment ended up being altogether suspended in Lebanon, as a result of staunch opposition by activists and some political factions.[75]

On 16 February 1979, seven men convicted of the ritual killing of the popular Kru traditional singer Moses Tweh, were publicly hanged at dawn in Harper.[76][77]

Hanging is the traditional method of capital punishment in Malaysia and has been used to execute people convicted of murder, drug trafficking and waging war against the government. The Barlow and Chambers execution was carried out as a result of new tighter drug regulations.

In Pakistan, hanging is the most common form of execution.

The last person executed by hanging in Portugal was Francisco Matos Lobos on 16 April 1842. Before that, it had been a common death penalty.

Hanging was commonly practised in the Russian Empire during the rule of the Romanov Dynasty as an alternative to impalement, which was used in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Hanging was abolished in 1868 by Alexander II after serfdom,[clarification needed] but was restored by the time of his death and his assassins were hanged. While those sentenced to death for murder were usually pardoned and sentences commuted to life imprisonment, those guilty of high treason were usually executed. This also included the Grand Duchy of Finland and Kingdom of Poland under the Russian crown. Taavetti Lukkarinen became the last Finn to be executed this way. He was hanged for espionage and high treason in 1916.

The hanging was usually performed by short drop in public. The gallows were usually either a stout nearby tree branch, as in the case of Lukkarinen, or a makeshift gallows constructed for the purpose.

After the October Revolution in 1917, capital punishment was, on paper, abolished, but continued to be used unabated against people perceived to be enemies of the regime. Under the Bolsheviks, most executions were performed by shooting, either by firing squad or by a single firearm. In 1943, hanging was restored primarily for German servicemen and native collaborators for atrocities committed against Soviet POWs and civilians. The last to be hanged were Andrey Vlasov and his companions in 1946.

In Singapore, long-drop hanging[17] is currently used as a mandatory punishment for crimes such as drug trafficking, murder and some types of kidnapping. It was introduced by the British, when they occupied Singapore and neighbouring Malaysia. It has also been used for punishing those convicted of unauthorised discharging of firearms.[78]

Hanging was abolished in Sri Lanka in 1956, but in 1959 it was brought back and later halted in 1978. In 1975, the day before the execution of Maru Sira, he had been overdosed by the prison guards to prevent him from escaping. On the day of his execution he was unconscious, so when he was brought to the gallows, he was slumped over on the trapdoor with a noose around his neck, and when the executioner pulled the lever, his execution was botched and he strangled.

Syria has publicly hanged people, such as two Jews in 1952, Israeli spy Eli Cohen in 1965, and a number of Jews accused of spying in 1969.[79][80][81]

According to a 19th-century report, members of the Alawite sect centred on Lattakia in Syria had a particular aversion towards being hanged, and the family of the condemned was willing to pay "considerable sums" to ensure its relations were impaled, instead of being hanged. As far as Burckhardt could make out, this attitude was based upon the Alawites' idea that the soul ought to leave the body through the mouth, rather than leave it in any other fashion.[82]

The Islamic State also used hanging post-mortem, after they executed alleged spies for the western-backed coalition in Deir ez-Zor by cutting their throats in a slaughterhouse, during the Islamic holiday of Eid al-Adha in 2016. They also used shooting, beheading, fire and other methods to execute people during their rule.[83]

As a form of judicial execution in England, hanging is thought to date from the Anglo-Saxon period.[84] Records of the names of British hangmen begin with Thomas de Warblynton in the 1360s;[citation needed] complete records extend from the 16th century to the last hangmen, Robert Leslie Stewart and Harry Allen, who conducted the last British executions in 1964.

Until 1868 hangings were performed in public. In London, the traditional site was at Tyburn, a settlement west of the City on the main road to Oxford, which was used on eight hanging days a year, though before 1865, executions had been transferred to the street outside Newgate Prison, Old Bailey, now the site of the Central Criminal Court.

Three British subjects were hanged after World War II after having been convicted of having helped Nazi Germany in its war against Britain. John Amery, the son of prominent British politician Leo Amery, became an expatriate in the 1930s, moving to France. He became involved in pre-war fascist politics, remained in what became Vichy France following France's defeat by Germany in 1940 and eventually went to Germany and later the German puppet state in Italy headed by Benito Mussolini. Captured by Italian partisans at the end of the war and handed over to British authorities, Amery was accused of having made propaganda broadcasts for the Nazis and of having attempted to recruit British prisoners of war for a Waffen SS regiment later known as the British Free Corps. Amery pleaded guilty to treason charges on 28 November 1945[85] and was hanged at Wandsworth Prison on 19 December 1945. William Joyce, an American-born Irishman who had lived in Britain and possessed a British passport, had been involved in pre-war fascist politics in the UK, fled to Nazi Germany just before the war began to avoid arrest by British authorities and became a naturalised German citizen. He made propaganda broadcasts for the Nazis, becoming infamous under the nickname Lord Haw Haw. Captured by British forces in May 1945, he was tried for treason later that year. Although Joyce's defence argued that he was by birth American and thus not subject to being tried for treason, the prosecution successfully argued that Joyce's pre-war British passport meant that he was a subject of the British Crown and he was convicted. After his appeals failed, he was hanged at Wandsworth Prison on 3 January 1946.[86] Theodore Schurch, a British soldier captured by the Nazis who then began working for the Italian and German intelligence services by acting as a spy and informer who would be placed among other British prisoners, was arrested in Rome in March 1945 and tried under the Treachery Act 1940. After his conviction, he was hanged at HM Prison Pentonville on 4 January 1946.

The Homicide Act 1957 created the new offence of capital murder, punishable by death, with all other murders being punishable by life imprisonment.

In 1965, Parliament passed the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act, temporarily abolishing capital punishment for murder for five years. The Act was renewed in 1969, making the abolition permanent. With the passage of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 and the Human Rights Act 1998, the death penalty was officially abolished for all crimes in both civilian and military cases. Following its complete abolition, the gallows were removed from Wandsworth Prison, where they remained in full working order until that year.

The last woman to be hanged was Ruth Ellis on 13 July 1955, by Albert Pierrepoint who was a prominent hangman in the 20th century in England. The last hangings in Britain took place in 1964, when Peter Anthony Allen was executed at Walton Prison in Liverpool. Gwynne Owen Evans was executed by Harry Allen at Strangeways Prison in Manchester. Both were executed for the murder of John Alan West.[87]

Hanging was also the method used in many colonies and overseas territories.[88]

In the UK, some felons are traditionally said to have been executed by hanging with a silken rope:

Hanging was one means by which Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony enforced religious and intellectual conformity on the whole community.[93] The best known hanging carried out by the Puritans, Mary Dyer was one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs.[94]

Capital punishment in the U.S. varies from state to state; it is outlawed in some states but used in most others. However, the death penalty under federal law is applicable in every state. Hanging is no longer used as a method of execution.

When Black pastor Denmark Vesey of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church was suspected of plotting to launch a slave rebellion in Charleston, South Carolina in 1822, 35 people, including Vesey, were judged guilty by a city-appointed court and were subsequently hanged, and the church was burned down.[95]

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Dakota uprising, led to the largest mass execution in the United States when 38 Sioux Indians, who were facing starvation and displacement, attacked white settlers, for which they were sentenced to death via hanging in Mankato, Minnesota in December 1862.[96] Originally, 303 had been sentenced to hang, but the convictions were reviewed by President Abraham Lincoln and the sentences of all but 38 were commuted.[97] In 2019, an historic apology was issued to the Dakota people for the mass hanging and the "trauma inflicted on Native people at the hands of state government."[96]

A total of 40 suspected Unionists were hanged in Gainesville, Texas in October 1862.[98] On 7 July 1865, four people involved in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln—Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt—were hanged at Fort McNair in Washington, D.C.

While relatively uncommon, hanging in chains has also been practiced (mainly during the colonial era), the first being a slave after the New York Slave Revolt of 1712. The last hanging in chains was in 1913, of John Marshall in West Virginia for murder.[99] The last public hanging in the United States (not including lynching, one of the last of which was Michael Donald in 1981) took place on 14 August 1936, in Owensboro, Kentucky. Rainey Bethea was executed for the rape and murder of 70-year-old Lischa Edwards. The execution was presided over by the first female sheriff in Kentucky, Florence Shoemaker Thompson.[100][101]

In California, Clinton Duffy, who served as warden of San Quentin State Prison between 1940 and 1952, presided over ninety executions.[102] He began to oppose the death penalty, and after his retirement, wrote a memoir entitled Eighty-Eight Men and Two Women in support of the movement to abolish the death penalty. The book documents several hangings gone wrong and describes how they led his predecessor, Warden James B. Holohan, to persuade the California Legislature to replace hanging with the gas chamber in 1937.[103][104]

Various methods of capital punishment have been replaced by lethal injection in most states and the federal government. Many states that offered hanging as an option have since eliminated the method. Condemned murderer Victor Feguer became the last inmate to be executed by hanging in the state of Iowa on 15 March 1963. Hanging was the preferred method of execution for capital murder cases in Iowa until 1965, when the death penalty was abolished and replaced with life imprisonment without parole. Barton Kay Kirkham was the last person to be hanged in Utah, preferring it over execution by firing squad. Laws in Delaware were changed in 1986 to specify lethal injection, except for those convicted before 1986 (who were still allowed to choose hanging). If a choice was not made, or the convict refused to choose injection, then hanging would become the default method. This was the case in the 1996 execution of Billy Bailey, the most recent hanging in American history; since then, no Delaware prisoner fit the category, and the state's gallows were later dismantled.

The upright jerker is a method of hanging that originated in the United States in the late 19th century. The person to be hanged is jerked into the air by weights and pulleys. It proved to be ineffective at breaking the neck of the condemned, and death by asphyxiation often occurred. In the United States, use of the method ceased in the late 1930s. However, Iran continues to intermittently employ a variant of this method, using a crane rather than a specially-designed mechanism of pulleys. The method has received heavy criticism from human rights organizations and the European Union.[105]

A completely different principle of hanging is to hang the convicted person from their legs, rather than from their neck, either as a form of torture, or as an execution method. In late medieval Germany, this came to be primarily associated with Jews accused of being thieves, called the Judenstrafe. The jurist Ulrich Tengler, in his Layenspiegel from 1509, describes the procedure as follows, in the section "Von Juden straff":[106]

To drag the Jew to the ordinary execution place between two angry or biting dogs. After dragging, to hang him from his feet by rope or chain at a designated gallows between the dogs, so that he is directed from life to death[107]

Guido Kisch showed that originally, this type of inverted hanging between two dogs was not a punishment specifically for Jews. Esther Cohen writes:[108]

The inverted hanging with the accompaniment of two dogs, originally reserved for traitors, was identified from the fourteenth century as the "Jewish execution", being practised in the later Middle Ages in both northern and Mediterranean Europe. The Jewish execution in Germany has been thoroughly studied by G. Kisch, who has argued convincingly that neither the inverted hanging nor the stringing up of dogs or wolves beside the victim were particularly Jewish punishments during the High Middle Ages. They first appeared as Jewish punishments in Germany only towards the end of the thirteenth century, never being recognized as exclusively Jewish penalties.

In France the inverted, animal-associated hanging came to be connected with Jews by the later Middle Ages. The inverted hanging of Jews is specifically mentioned in the old customs of Burgundy in the context of animal hanging. The custom, dogs and all, was still in force in Paris shortly before the final expulsion of the Jews in 1394.

In Spain 1449, during a mob attack against the Marranos (Jews nominally converted to Christianity), the Jews resisted, but lost and several of them were hanged up by the feet.[109] The first attested German case for a Jew being hanged by the feet is from 1296, in present-day Soultzmatt.[110] Some other historical examples of this type of hanging within the German context are one Jew in Hennegau 1326, two Jews hanged in Frankfurt 1444,[111] one in Halle in 1462,[112] one in Dortmund 1486,[113] one in Hanau 1499,[111] one in Breslau 1505,[114] one in Württemberg 1553,[115] one in Bergen 1588,[111] one in Öttingen 1611,[116] one in Frankfurt 1615 and again in 1661,[111] and one condemned to this punishment in Prussia in 1637.[117]

The details of the cases vary widely: In the 1444 Frankfurt cases and the 1499 Hanau case, the dogs were dead prior to being hanged, and in the late 1615 and 1661 cases in Frankfurt, the Jews (and dogs) were merely kept in this torture for half an hour, before being garroted from below. In the 1588 Bergen case, all three victims were left hanging till they were dead, ranging from 6 to 8 days after being hanged. In the Dortmund 1486 case, the dogs bit the Jew to death while hanging. In the 1611 Öttingen case, the Jew "Jacob the Tall" thought to blow up the Deutsche Ordenhaus with gunpowder after having burgled it. He was strung up between two dogs, and a large fire was made close to him, and he expired after half an hour under this torture. In the 1553 Württemberg case, the Jew chose to convert to Christianity after hanging like this for 24 hours; he was then given the mercy to be hanged in the ordinary manner, from the neck, and without the dogs beside him. In the 1462 Halle case, the Jew Abraham also converted after 24 hours hanging upside down, and a priest went up on a ladder and baptised him. For two more days, Abraham was left hanging, while the priest argued with the city council that a true Christian should not be punished in this way. On the third day, Abraham was granted a reprieve, and was taken down, but died 20 days later in the local hospital having meanwhile suffered in extreme pain. In the 1637 case, where the Jew had murdered a Christian jeweller, the appeal to the empress was successful, and out of mercy, the Jew was condemned to be merely pinched with glowing pincers, have hot lead dripped into his wounds, and then be broken alive on the wheel.

Some of the reported cases may be myths, or wandering stories. The 1326 Hennegau case, for example, deviates from the others in that the Jew was not a thief, but was suspected (even though he was a convert to Christianity) of having struck an al fresco painting of Virgin Mary, so that blood had begun to seep down the wall from the painting. Even under all degrees of judicial torture, the Jew denied performing this sacrilegious act, and was therefore exonerated. Then a brawny smith demanded from him a trial by combat, because, supposedly, in a dream the Virgin herself had besought the smith to do so. The court accepted the smith's challenge, he easily won the combat against the Jew, who was duly hanged up by the feet between two dogs. To add to the injury, one let him be slowly roasted as well as hanged.[118] This is a very similar story to one told in France, in which a young Jew threw a lance at the head of a statue of the Virgin, so that blood spurted out of it. There was inadequate evidence for a normal trial, but a frail old man asked for trial by combat, and bested the young Jew. The Jew confessed his crime, and was hanged by his feet between two mastiffs.[119]

The features of the earliest attested case, that of a Jewish thief hanged by the feet in Soultzmatt in 1296 are also rather divergent from the rest. The Jew managed somehow, after he had been left to die, to twitch his body in such a manner that he could hoist himself up on the gallows and free himself. At that time, his feet were so damaged that he was unable to escape, and when he was discovered 8 days after he had been hanged, he was strangled to death by the townspeople.[120]

As late as in 1699 Celle, the courts were sufficiently horrified at how the Jewish leader of a robber gang (condemned to be hanged in the normal manner) declared blasphemies against Christianity, that they made a ruling on the post mortem treatment of Jonas Meyer. After 3 days, his corpse was cut down, his tongue cut out, and his body was hanged up again, but this time from its feet.[121]

Guido Kisch writes that the first instance he knows where a person in Germany was hanged up by his feet between two dogs until he died occurred about 1048, some 250 years earlier than the first attested Jewish case. This was a knight called Arnold, who had murdered his lord; the story is contained in Adam of Bremen's History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen.[122] Another example of a non-Jew who suffered this punishment as a torture, in 1196 Richard, Count of Acerra, was one of those executed by Henry VI in the suppression of the rebelling Sicilians:[123]

He [Henry VI] held a general court in Capua, at which he ordered that the count first be drawn behind a horse through the squares of Capua, and then hanged alive head downwards. The latter was still alive after two days when a certain German jester called Leather-Bag [Follis], hoping to please the emperor, tied a large stone to his neck and shamefully put him to death

A couple of centuries earlier, in France 991, a viscount Walter nominally owing his allegiance to the French King Hugh Capet chose, on instigation of his wife, to join the rebellion under Odo I, Count of Blois. When Odo found out he had to abandon Melun after all, Walter was duly hanged before the gates, whereas his wife, the fomentor of treason, was hanged by her feet, causing much merriment and jeers from Hugh's soldiers as her clothes fell downwards revealing her naked body, although it is not wholly clear if she died in that manner.[124]

During Queen Elizabeth I's reign, the following was written concerning those who stole a ship from the Royal Navy:[125]

If anye one practysed to steale awaye anye of her Majesty's shippes, the captaine was to cause him to be hanged by the heels untill his braines were beaten out against the shippe's sides, and then to be cutt down and lett fall intoe the sea.

In 1713, Juraj Jánošík, a semi-legendary Slovak outlaw and folk hero, was sentenced to be hanged from his left rib. He was left to slowly die.[126]

The German physician Gottlob Schober (1670–1739),[127] who worked in Russia from 1712, notes that a person could hang from the ribs for about three days prior to expiring, his primary pain being that of extreme thirst. He thought this degree of insensitivity was something peculiar to the Russian mentality.[128]

The Dutch in Suriname were also in the habit of hanging a slave from the ribs, a custom amongst the African tribes from whom they were originally purchased. John Gabriel Stedman stayed in South America from 1772 to 1777 and described the method as told by a witness:[129]

Not long ago, (continued he) I saw a black "man suspended alive from a gallows by the ribs, between which, with a knife, was first made an incision, and then clinched an iron hook with a chain: in this manner he kept alive three days, hanging with his head "and feet downwards, and catching with his tongue the "drops of water" (it being in the rainy season) that were "flowing down his bloated breast. Notwithstanding all this, he never complained, and even upbraided a negro "for crying while he was flogged below the gallows, by calling out to him: "You man?—Da boy fasy? Are you a man? you behave like a boy". Shortly after which he was knocked on the head by the commiserating sentry, who stood over him, with the butt end of his musket.

William Blake was specially commissioned to make illustrations to Stedman's narrative.[130]

The standard past tense and past participle form of the verb "hang", in the sense of this article, is "hanged",[131][132][133] although some dictionaries give "hung" as an alternative.[134][135]

It was not until the introduction of the standard drop by Dr. Samuel Haughton in 1866, and the so-called long drop by William Marwood in 1872 that hanging became a standard, humane means to achieve instantaneous death.

Before the invention of the hinged trapdoor through which the victim was dropped, he or she was 'turned off' or 'twisted' by the hangman who pulled the ladder away.

... condemned persons still mounted a ladder which was turned round, leaving them dangling. This led to the phrase 'turned off'—they were literally turned off the ladder.