Голландский ( эндоним : Nederlands [ˈneːdərlɑnts] ) —западногерманский язык, на котором говорят около 25 миллионов человек как на родном языке[4]и 5 миллионов как на втором языке, и который являетсятретьим по распространенностигерманским языком. В Европе голландский является родным языком большей части населения НидерландовиФландрии(включая 60% населенияБельгии).[2][3]Голландский был одним из официальных языковЮжной Африкидо 1925 года, когда его заменилафрикаанс, отдельный, но частичновзаимопонятный дочерний язык[5]голландского.[a]Африкаанс, в зависимости от используемого определения, может считатьсяродственным языком,[6]на котором говорят, в некоторой степени, по крайней мере 16 миллионов человек, в основном вЮжной АфрикеиНамибии,[b]и который развился изкапских голландцев.

В Южной Америке это родной язык большинства населения Суринама , и на нем говорят как на втором или третьем языке в полиглотных островных странах Карибского бассейна Аруба , Кюрасао и Синт-Мартен . Все эти страны признали голландский одним из своих официальных языков и так или иначе участвуют в Союзе голландского языка . [7] В голландских муниципалитетах Карибского бассейна ( Синт-Эстатиус , Саба и Бонайре ) голландский является одним из официальных языков. [8] В Азии голландский использовался в Голландской Ост-Индии (теперь в основном Индонезия ) ограниченной образованной элитой, составляющей около 2% от общей численности населения, включая более 1 миллиона коренных индонезийцев, [9] пока он не был запрещен в 1957 году, но впоследствии запрет был снят. [10] Примерно пятая часть индонезийского языка может быть прослежена до голландского, включая многие заимствованные слова . [10] Гражданский кодекс Индонезии официально не переведён, и оригинальная версия на голландском языке, датируемая колониальными временами, остаётся официальной версией. [11] До полумиллиона носителей языка проживают в США, Канаде и Австралии вместе взятых, [c] а исторические языковые меньшинства, находящиеся на грани исчезновения, остаются в некоторых частях Франции [12] и Германии. [d]

Голландский язык является одним из ближайших родственников немецкого и английского языков [e] и, как говорят в разговорной речи, находится «примерно посередине» между ними. [f] Голландский язык, как и английский, не претерпел верхненемецкого сдвига согласных , не использует германский умлаут в качестве грамматического маркера, в значительной степени отказался от использования сослагательного наклонения и выровнял большую часть своей морфологии , включая большую часть своей системы падежей . [g] Однако черты, общие с немецким языком, включают сохранение двух-трех грамматических родов — хотя и с небольшими грамматическими последствиями [h] — а также использование модальных частиц , [13] оглушительное окончание и (схожий) порядок слов . [i] Голландский словарь в основном германский; он включает немного больше романских заимствований , чем немецкий, но гораздо меньше, чем английский. [j]

В Бельгии, Нидерландах и Суринаме официальное название голландского языка — Nederlands [14] [15] (исторически Nederlandsch до голландских орфографических реформ ). [16] Иногда Vlaams (« фламандский ») также используется для описания стандартного голландского языка во Фландрии , тогда как Hollands (« голландский ») иногда используется как разговорный термин для стандартного языка в центральной и северо-западной части Нидерландов. [17]

В английском языке прилагательное Dutch используется как существительное для обозначения языка Нидерландов и Фландрии. Слово происходит от протогерманского *þiudiskaz . Основа этого слова, *þeudō , на протогерманском языке означала «люди», а *-iskaz был суффиксом, образующим прилагательное, из которых -ish является современной английской формой. [18] Theodiscus был его латинизированной формой [19] и использовался как прилагательное, относящееся к германским наречиям раннего Средневековья . В этом смысле он означал «язык простых людей». Термин использовался в противопоставлении латыни , неродному языку письма и католической церкви . [20] Впервые он был зафиксирован в 786 году, когда епископ Остии написал папе Адриану I о синоде, состоявшемся в Корбридже , Англия , где решения были записаны « tam Latine quam theodisce », что означает «на латыни, а также на общепринятом языке». [21] [22] [23]

Согласно гипотезе Де Грауве, в северной части Западной Франкии (т. е. на территории современной Бельгии) термин приобрел новое значение в период раннего Средневековья , когда в контексте крайне дихроматического лингвистического ландшафта он стал антонимом * walhisk (носители романского языка, в частности, древнефранцузского ) . [ 24] Слово, которое теперь переводится как dietsc (юго-западный вариант) или duutsc (центральный и северный вариант), может относиться как к самому голландскому языку, так и к более широкой германской категории в зависимости от контекста. В эпоху Высокого Средневековья термин « Dietsc / Duutsc » все чаще использовался как обобщающий термин для определенных германских диалектов, на которых говорили в Нидерландах , его значение в значительной степени неявно определялось региональной ориентацией средневекового голландского общества: за исключением высших эшелонов духовенства и знати, мобильность была в значительной степени статичной, и, следовательно, хотя «голландский» можно было бы также использовать в его более раннем значении, ссылаясь на то, что сегодня называют германскими диалектами в отличие от романских диалектов , во многих случаях он понимался или подразумевался как относящийся к языку, который сейчас известен как голландский. [25]

В Нидерландах Dietsch или его ранняя современная голландская форма Duytsch как эндоним для голландского языка постепенно вышла из употребления и была постепенно заменена голландским эндонимом Nederlands . Это обозначение (впервые засвидетельствованное в 1482 году) началось при бургундском дворе в 15 веке, хотя использование neder , laag , bas и lower («нижний» или «низкий») для обозначения области, известной как Нидерландские страны, восходит к более раннему времени, когда римляне называли этот регион Germania Inferior («Нижняя» Германия). [26] [27] [28] Это ссылка на нижнее расположение Нидерландов в дельте Рейна-Мааса-Шельды около Северного моря .

С 1551 года обозначение Nederlands получило сильную конкуренцию со стороны названия Nederduytsch (буквально «нижнеголландский», голландский использовался в своем архаичном смысле, охватывающем все континентальные западногерманские языки). Это калька вышеупомянутой римской провинции Germania Inferior и попытка ранних голландских грамматистов придать своему языку больше престижа, связав его с римскими временами. Аналогичным образом, Hoogduits («верхненемецкий») и Overlands («верхнеландский») вошли в употребление как голландский экзоним для различных немецких диалектов, используемых в соседних немецких государствах. [29] Использование Nederduytsch было популярно в 16 веке, но в конечном итоге проиграло Nederlands в конце 18 века, а (Hoog)Duytsch утвердился как голландский экзоним для немецкого в тот же период.

В 19 веке в Германии произошел подъем категоризации диалектов, и немецкие диалектологи назвали немецкие диалекты, на которых говорили в горном юге Германии, Hochdeutsch («верхненемецкие»). Впоследствии немецкие диалекты, на которых говорили на севере, были обозначены как Niederdeutsch («нижненемецкие»). Названия для этих диалектов были калькированы голландскими лингвистами как Nederduits и Hoogduits . В результате Nederduits больше не служит синонимом голландского языка. В 19 веке термин « Diets » был возрожден голландскими лингвистами и историками, а также как поэтическое название для средненидерландского языка и его литературы . [30]

Древненидерландский можно различить примерно в то же время, что и древнеанглийский (англосаксонский), древневерхненемецкий , древнефризский и древнесаксонский . Эти названия происходят от современных стандартных языков . В эту эпоху еще не было разработано стандартных языков, в то время как идеальный западногерманский диалектный континуум сохранялся; разделение отражает условный будущий вклад диалектных групп в более поздние языки. Ранняя форма нидерландского языка представляла собой набор франконских диалектов, на которых говорили салические франки в V веке. Они развились через средненидерландский в современный нидерландский в течение пятнадцати столетий. [31] В этот период они вытеснили древнефризский язык с западного побережья на север Нидерландов и повлияли или даже заменили древнесаксонский, на котором говорили на востоке (смежном с нижненемецкой областью). С другой стороны, голландский язык был заменен на соседних землях в современной Франции и Германии. Разделение на древне-, средне- и новонидерландский в основном условно, поскольку переход между ними был очень постепенным. Один из немногих моментов, когда лингвисты могут обнаружить нечто вроде революции, — это когда появился и быстро утвердился голландский стандартный язык. Развитие голландского языка иллюстрируется следующим предложением на древнего, средне- и современного голландского:

Среди индоевропейских языков голландский язык сгруппирован в германские языки , что означает, что он имеет общего предка с такими языками, как английский, немецкий и скандинавские языки . Все германские языки подчиняются закону Гримма и закону Вернера о звуковых сдвигах, которые возникли в протогерманском языке и определяют основные черты, отличающие их от других индоевропейских языков. Предполагается, что это произошло примерно в середине первого тысячелетия до нашей эры в доримский североевропейский железный век . [34]

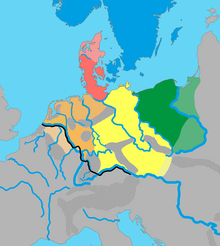

Германские языки традиционно делятся на три группы: восточные (ныне вымершие), западные и северогерманские . [35] Они оставались взаимопонятными на протяжении всего периода переселения народов . Голландский язык является частью западногерманской группы, которая также включает английский, шотландский , фризский , нижненемецкий (древнесаксонский) и верхненемецкий . Он характеризуется рядом фонологических и морфологических новшеств, не встречающихся в северо- или восточногерманских языках. [36] Западногерманские разновидности того времени, как правило, делятся на три диалектные группы: ингвеонские (североморские германские), иствеонские (везер-рейнские германские) и ирминонские (эльбские германские). Похоже, что франкские племена в основном вписываются в иствеонскую диалектную группу с определенными ингвеонскими влияниями на северо-западе, которые все еще видны в современном голландском.

Франкский язык сам по себе не засвидетельствован напрямую, единственным возможным исключением является надпись Bergakker , найденная около голландского города Тиль , которая может представлять собой первичную запись франкского языка V века. Хотя некоторые топонимы, зафиксированные в римских текстах, такие как vadam (современный голландский: wad , английский: "mudflat"), можно было бы считать старейшими отдельными "голландскими" словами, надпись Bergakker дает старейшее свидетельство голландской морфологии. Однако интерпретации остальной части текста не имеют единого мнения. [37]

Франки появились в южных Нидерландах ( салийские франки ) и центральной Германии ( рипуарские франки ), а затем спустились в Галлию . Название их королевства сохранилось в названии Франции. Хотя они правили галло-римлянами почти 300 лет, их язык, франкский , вымер на большей части Франции и был заменен более поздними формами языка по всему Люксембургу и Германии примерно в 7 веке. Во Франции он был заменен старофранцузским ( романским языком со значительным древнефранкским влиянием).

Однако древнефранкский язык не вымер в целом, поскольку на нем продолжали говорить в Нидерландах, и впоследствии он превратился в то, что сейчас называется древненижнефранкским или древнеголландским в Нидерландах. Фактически, древнефранкский язык можно реконструировать из древнеголландских и франкских заимствований в древнефранцузском. [38]

Термин «древнеголландский» или «древненижнефранкский» [39] [40] относится к набору франконских диалектов (т. е. западногерманских разновидностей, которые, как предполагается, произошли от франкского ), на которых говорили в Нидерландах в период раннего Средневековья , примерно с V по XII век. [41] Древнеголландский язык в основном зафиксирован на фрагментарных реликвиях, а слова были реконструированы из среднеголландских и древнеголландских заимствований во французском языке. [42] Древнеголландский язык считается первичной стадией в развитии отдельного голландского языка. На нем говорили потомки салических франков , которые занимали то, что сейчас является южными Нидерландами , северной Бельгией , частью северной Франции и частями Нижнерейнских регионов Германии.

Сдвиг согласных в верхненемецком языке, перемещаясь по Западной Европе с юга на запад, вызвал дифференциацию с центрально- и верхнефранкским в Германии. Последний в результате эволюционировал (вместе с алеманнским , баварским и ломбардским ) в древневерхненемецкий. Примерно в то же время закон носового спиранта в ингвеонском языке, перемещаясь по Западной Европе с запада на восток, привел к развитию древнеанглийского ( или англосаксонского), древнефризского и древнесаксонского языков . Почти не подвергшийся влиянию ни одного из этих направлений, древненидерландский язык, вероятно, оставался относительно близким к исходному языку франков. Однако язык претерпел собственные изменения, такие как очень раннее оглушительное окончание . Фактически, находка в Бергакере указывает на то, что язык, возможно, уже испытал этот сдвиг во время древнефранкского периода.

.jpg/440px-Gallee_(cropped).jpg)

Подтверждения древнеголландских предложений крайне редки. Язык в основном записан на фрагментарных реликвиях, а слова были реконструированы из средненидерландского и заимствованных слов из древнеголландского в других языках. [42] Самое древнее из зафиксированных найдено в Салическом законе . В этом франкском документе, написанном около 510 года, было идентифицировано самое древнее голландское предложение: Maltho thi afrio lito («Я говорю тебе, я освобождаю тебя, крепостной»), используемое для освобождения крепостного. Еще один старый фрагмент голландского языка — Visc flot aftar themo uuatare («Рыба плавала в воде»). Самый старый сохранившийся более крупный голландский текст — это Утрехтский крестильный обет (776–800), начинающийся с Forsachistu diobolae ... ec forsacho diabolae (досл.: «Оставлю тебя, дьявол? ... Я оставлю дьявола»). Если говорить только о поэтическом содержании, то самым известным предложением на древнеголландском языке, вероятно, является Hebban olla vogala nestas hagunnan, hinase hic enda tu, wat unbidan we nu («Все птицы начали вить гнезда, кроме меня и тебя, чего же мы ждем»), датируемое примерно 1100 годом, написанное фламандским монахом в монастыре в Рочестере , Англия . Поскольку предложение воздействует на воображение, его часто ошибочно называют самым старым предложением на голландском языке.

Древнеголландский естественным образом эволюционировал в среднеголландский . Год 1150 часто упоминается как время разрыва, но на самом деле он знаменует собой время обильного голландского письма; в этот период развивалась богатая средневековая голландская литература . В то время не было всеобъемлющего стандартного языка ; среднеголландский — это скорее собирательное название для ряда тесно связанных, взаимно понятных диалектов, на которых говорили в бывшей древнеголландской области. В то время как древнеголландские фрагменты очень трудно читать неподготовленным носителям современного голландского языка, различные литературные произведения среднеголландского языка несколько более доступны. [43] Наиболее заметное различие между древне- и среднеголландским заключается в особенности речи, известной как редукция гласных , при которой гласные в безударных слогах выравниваются до шва .

Диалектные области Среднеголландского языка были затронуты политическими границами. Сфера политического влияния определенного правителя часто также создавала сферу языкового влияния, при этом язык в пределах области становился более однородным. После современных политических делений они располагаются в порядке важности:

Процесс стандартизации начался в Средние века , особенно под влиянием бургундского герцогского двора в Дижоне ( Брюссель после 1477 года). Диалекты Фландрии и Брабанта были наиболее влиятельными в это время. Процесс стандартизации стал намного сильнее в начале 16-го века, в основном на основе городского диалекта Антверпена . Падение Антверпена в 1585 году испанской армией привело к бегству в северные Нидерланды, где Голландская республика объявила о своей независимости от Испании. Это повлияло на городские диалекты провинции Голландия . В 1637 году был сделан еще один важный шаг к единому языку, [47] когда был создан Statenvertaling , первый крупный перевод Библии на голландский язык, который могли понимать люди со всей новой республики. Он использовал элементы из различных, даже нижнесаксонских , диалектов, но был преимущественно основан на городских диалектах Голландии после 16-го века. [48]

В Южных Нидерландах (ныне Бельгия и Люксембург) развитие событий было иным. При последующем испанском , австрийском и французском правлении стандартизация голландского языка зашла в тупик. Государство, законодательство и все большее образование использовали французский язык, однако более половины населения Бельгии говорили на разновидности голландского языка. В течение 19-го века Фламандское движение отстаивало права носителей голландского языка, в основном называемых «фламандцами». Однако диалектные различия были серьезным недостатком перед лицом стандартизированной франкофонии . [49] Поскольку стандартизация является длительным процессом, голландскоязычная Бельгия ассоциировала себя со стандартным языком, который уже развивался в Нидерландах на протяжении столетий. Таким образом, ситуация в Бельгии по сути ничем не отличается от ситуации в Нидерландах, хотя есть заметные различия в произношении, сопоставимые с различиями в произношении между стандартным британским и стандартным американским английским. [50] В 1980 году Нидерланды и Бельгия заключили Договор о языковом союзе . В этом договоре закреплен принцип, согласно которому обе страны должны согласовывать свою языковую политику, в том числе в отношении общей системы правописания.

Голландский язык принадлежит к своей собственной западногерманской подгруппе, нижнефранкским языкам, в паре со своим родственным языком лимбургским или восточно-нижнефранкским. Его ближайшим родственником является взаимно понятный дочерний язык африкаанс. Другие западногерманские языки, родственные голландскому, — это немецкий , английский и нестандартизированные языки нижненемецкий и идиш .

Голландский язык выделяется сочетанием некоторых ингвеонских характеристик (последовательно встречающихся в английском и фризском языках и уменьшающихся по интенсивности с запада на восток по континентальной западногерманской плоскости) с доминирующими истваонскими характеристиками, некоторые из которых также включены в немецкий язык. В отличие от немецкого языка, голландский язык (за исключением лимбургского) вообще не подвергся влиянию перемещения верхненемецкого согласного с юга на север и претерпел некоторые собственные изменения. [k] Накопление этих изменений со временем привело к появлению отдельных, но связанных между собой стандартных языков с различной степенью сходства и различий между ними. Для сравнения западногерманских языков см. разделы Фонология, Грамматика и Лексика.

Голландские диалекты — это в первую очередь диалекты, которые связаны с голландским языком и на которых говорят в той же языковой области, что и голландский литературный язык . Хотя они находятся под сильным влиянием литературного языка, некоторые из них остаются удивительно [ требуется ссылка ] разнообразными и встречаются в Нидерландах , а также в Брюссельском и Фламандском регионах Бельгии . Области, в которых на них говорят, часто соответствуют бывшим средневековым графствам и герцогствам. Нидерланды (но не Бельгия) различают диалект и streektaal (« региональный язык »). Эти слова на самом деле больше политические , чем лингвистические, поскольку региональный язык объединяет большую группу очень разных разновидностей. Так обстоит дело с диалектом Гронингена , который считается разновидностью голландского нижнесаксонского регионального языка, но он относительно отличается от других нижнесаксонских разновидностей. Кроме того, некоторые голландские диалекты более далеки от голландского литературного языка, чем некоторые разновидности регионального языка. В Нидерландах проводится еще одно различие между региональным языком и отдельным языком, как в случае со ( стандартизированным ) западно-фризским языком . На нем говорят наряду с голландским в провинции Фрисландия .

На голландских диалектах и региональных языках говорят не так часто, как раньше, особенно в Нидерландах. Недавние исследования Герта Дриссена показывают, что использование диалектов и региональных языков как среди взрослых голландцев, так и среди молодежи находится в сильном упадке. В 1995 году 27 процентов взрослого населения Нидерландов регулярно говорили на диалекте или региональном языке, но в 2011 году их было не более 11 процентов. В 1995 году 12 процентов детей младшего школьного возраста говорили на диалекте или региональном языке, но в 2011 году этот показатель снизился до четырех процентов. Из официально признанных региональных языков больше всего говорят на лимбургском (в 2011 году среди взрослых 54%, среди детей 31%), а меньше всего — на нижнесаксонском (взрослые 15%, дети 1%). Спад западно -фризского языка во Фрисландии занимает среднее положение (взрослые 44%, дети 22%). Диалекты чаще всего используются в сельской местности, но во многих городах есть свой городской диалект. Например, в городе Гент очень отчетливо слышны звуки "g", "e" и "r", которые сильно отличаются от окружающих деревень. Брюссельский диалект сочетает в себе брабантский язык со словами, заимствованными из валлонского и французского языков .

Некоторые диалекты до недавнего времени имели расширения за пределы границ других стандартных языковых областей. В большинстве случаев сильное влияние стандартного языка нарушило диалектный континуум . Примерами являются диалект Гронингена , а также близкородственные ему разновидности в соседней Восточной Фризии (Германия). Клеверландский — это диалект, на котором говорят в южной части Гелдерланда , северной оконечности Лимбурга и северо-востоке Северного Брабанта (Нидерланды), а также в соседних частях Северного Рейна-Вестфалии (Германия). Лимбургский ( Limburgs ) говорят в Лимбурге (Бельгия) , а также в остальной части Лимбурга (Нидерланды) и он простирается через границу с Германией. Западно-фламандский ( Westvlaams ) говорят в Западной Фландрии , западной части Зеландской Фландрии , а также во Французской Фландрии , где он фактически вымер, уступив место французскому.

Группа западнофламандских диалектов, на которых говорят в Западной Фландрии и Зеландии , настолько отлична, что ее можно было бы рассматривать как отдельный языковой вариант, хотя сильное значение языка в бельгийской политике не позволило бы правительству классифицировать их как таковые. Странность диалекта заключается в том, что звонкий велярный фрикативный согласный (пишется как «g» на голландском языке) сменяется звонким гортанным фрикационным согласным (пишется как «h» на голландском языке), в то время как буква «h» становится немой (как во французском языке). В результате, когда западнофламандцы пытаются говорить на стандартном голландском языке, они часто не могут произнести звук «g» и произносят его похоже на звук «h». Это не оставляет, например, никакой разницы между « hold » (герой) и « geld » (деньги). Или в некоторых случаях они знают о проблеме и гиперисправляют «h» на звонкий велярный фрикативный согласный или звук «g», снова не оставляя никакой разницы. Западно-фламандский вариант, на котором исторически говорят в соседних частях Франции, иногда называют французским фламандским и относят к языкам французского меньшинства . Однако только очень небольшое и стареющее меньшинство франко-фламандского населения все еще говорит и понимает западно-фламандский.

На голландском говорят в Голландии и Утрехте , хотя первоначальные формы этого диалекта (которые находились под сильным влиянием западно-фризского субстрата и, с XVI века, брабантских диалектов ) сейчас относительно редки. Городские диалекты Рандстада , которые являются голландскими диалектами, не сильно отличаются от стандартного голландского, но есть четкая разница между городскими диалектами Роттердама , Гааги , Амстердама и Утрехта . В некоторых сельских голландских районах все еще используются более аутентичные голландские диалекты, особенно к северу от Амстердама. Другая группа диалектов, основанных на голландском, — это те, на которых говорят в городах и крупных поселках Фрисландии , где они частично вытеснили западно-фризский в XVI веке и известны как Stadsfries («городской фризский»). Голландский язык, а также, в частности, клеверландский и северобрабантский, но без городского фризского, являются центральнонидерландскими диалектами .

Брабантский язык назван в честь исторического герцогства Брабант , которое в основном соответствовало провинциям Северный Брабант и южный Гелдерланд , бельгийским провинциям Антверпен и Фламандский Брабант , а также Брюсселю (где его носители языка стали меньшинством) и провинции Валлонский Брабант . Брабантский язык распространяется на небольшие части на западе Лимбурга , в то время как его сильное влияние на восточнофламандский язык Восточной Фландрии и восточнозеландской Фландрии [51] ослабевает к западу. В небольшой области на северо-западе Северного Брабанта ( Виллемстад )говорят на голландском языке. Традиционно диалекты клеверландского языка отличают от брабантского, но для этого нет никаких объективных критериев, кроме географии. Более 5 миллионов человек живут в районе, где какая-либо форма брабантского языка является преобладающим разговорным языком из 22 миллионов говорящих на голландском языке в этом районе. [52] [53]

Лимбургский , на котором говорят как в бельгийском Лимбурге , так и в нидерландском Лимбурге и в прилегающих частях Германии, считается диалектом в Бельгии, в то время как в Нидерландах он получил официальный статус регионального языка. Лимбургский язык подвергся влиянию прибрежных диалектов, таких как кёльнский диалект , и получил несколько иное развитие с позднего Средневековья.

Две группы диалектов получили официальный статус регионального языка (или streektaal ) в Нидерландах. Как и несколько других групп диалектов, обе являются частью диалектного континуума, который продолжается через национальные границы.

Область нижнесаксонского диалекта Нидерландов охватывает провинции Гронинген , Дренте и Оверэйссел , а также части провинций Гелдерланд , Флеволанд , Фрисландия и Утрехт . Эта группа, которая не является нижнефранконской, а нижнесаксонской и близка к соседнему нижненемецкому, была повышена Нидерландами (и Германией) до юридического статуса streektaal ( регионального языка ) в соответствии с Европейской хартией региональных языков или языков меньшинств . Он считается нидерландским по ряду причин. С 14-го по 15-й век его городские центры ( Девентер , Зволле , Кампен , Зютфен и Дусбург ) все больше подвергались влиянию западного письменного голландского языка и стали лингвистически смешанной областью. С 17-го века он постепенно интегрировался в область нидерландского языка. [54] Нидерландский нижнесаксонский раньше находился на одном конце нижненемецкого диалектного континуума . Однако национальная граница уступила место границам диалектов, совпадающим с политической границей, поскольку традиционные диалекты находятся под сильным влиянием национальных стандартных вариантов. [55]

Будучи несколько неоднородной группой нижнефранконских диалектов, лимбургский язык получил официальный статус регионального языка в Нидерландах и Германии, но не в Бельгии. Благодаря этому официальному признанию он получает защиту в соответствии с главой 2 Европейской хартии региональных языков или языков меньшинств .

Африкаанс , хотя в значительной степени и взаимопонятен с голландским, обычно не считается диалектом, а отдельным стандартизированным языком . На нем говорят в Южной Африке и Намибии. Будучи дочерним языком голландского, африкаанс в основном развивался из голландских диалектов 17-го века, но подвергся влиянию различных других языков Южной Африки.

Западно-фризский ( Westerlauwers Fries ), наряду с затерландским фризским и северо-фризским , произошли от той же ветви западно-германских языков, что и древнеанглийский (т. е. англо-фризский ), и поэтому генетически более тесно связаны с английским и шотландским, чем с голландским. Однако различные влияния на соответствующие языки, особенно влияние нормандского французского на английский и голландского на западно-фризский, сделали английский язык совершенно отличным от западно-фризского, а западно-фризский язык менее отличным от голландского, чем от английского. Несмотря на сильное влияние голландского литературного языка, он не является взаимопонятным с голландским и считается родственным языком голландскому, как английский и немецкий. [56]

Примерное распределение носителей голландского языка по всему миру:

Голландский язык является официальным языком Нидерландов (не закреплен в конституции , но в административном праве [61] [l] ), Бельгии, Суринама, голландских карибских муниципалитетов (Синт-Эстатиус, Саба и Бонайре), Арубы , Кюрасао и Синт-Мартена . Голландский язык также является официальным языком нескольких международных организаций, таких как Европейский союз [65] , Союз южноамериканских наций [66] и Карибское сообщество . На академическом уровне голландский язык преподается примерно в 175 университетах в 40 странах. Около 15 000 студентов по всему миру изучают голландский язык в университетах. [67]

In Europe, Dutch is the majority language in the Netherlands (96%) and Belgium (59%) as well as a minority language in Germany and northern France's French Flanders. Though Belgium as a whole is multilingual, three of the four language areas into which the country is divided (Flanders, francophone Wallonia, and the German-speaking Community) are largely monolingual, with Brussels being bilingual. The Netherlands and Belgium produce the vast majority of music, films, books and other media written or spoken in Dutch.[68] Dutch is a monocentric language, at least what concerns its written form, with all speakers using the same standard form (authorised by the Dutch Language Union) based on a Dutch orthography defined in the so-called "Green Booklet" authoritative dictionary and employing the Latin alphabet when writing; however, pronunciation varies between dialects. Indeed, in stark contrast to its written uniformity, Dutch lacks a unique prestige dialect and has a large dialectal continuum consisting of 28 main dialects, which can themselves be further divided into at least 600 distinguishable varieties.[69][70] In the Netherlands, the Hollandic dialect dominates in national broadcast media while in Flanders Brabantian dialect dominates in that capacity, making them in turn unofficial prestige dialects in their respective countries.

Outside the Netherlands and Belgium, the dialect spoken in and around the German town of Kleve (Kleverlandish) is historically and genetically a Low Franconian variety. In North-Western France, the area around Calais was historically Dutch-speaking (West Flemish), of which an estimated 20,000 are daily speakers. The cities of Dunkirk, Gravelines and Bourbourg only became predominantly French-speaking by the end of the 19th century. In the countryside, until World War I, many elementary schools continued to teach in Dutch, and the Catholic Church continued to preach and teach the catechism in Dutch in many parishes.[71]

During the second half of the 19th century, Dutch was banned from all levels of education by both Prussia and France and lost most of its functions as a cultural language. In both Germany and France, the Dutch standard language is largely absent, and speakers of these Dutch dialects will use German or French in everyday speech. Dutch is not afforded legal status in France or Germany, either by the central or regional public authorities, and knowledge of the language is declining among younger generations.[72]

As a foreign language, Dutch is mainly taught in primary and secondary schools in areas adjacent to the Netherlands and Flanders. In French-speaking Belgium, over 300,000 pupils are enrolled in Dutch courses, followed by over 23,000 in the German states of Lower Saxony and North Rhine-Westphalia, and about 7,000 in the French region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais (of which 4,550 are in primary school).[73] At an academic level, the largest number of faculties of neerlandistiek can be found in Germany (30 universities), followed by France (20 universities) and the United Kingdom (5 universities).[73][74]

.jpg/440px-Kantor_Pos_Indonesia_cabang_Telanaipura_-_Telanaipura,_Kota_Jambi,_JA_(23_April_2021).jpg)

Despite the Dutch presence in Indonesia for almost 350 years, as the Asian bulk of the Dutch East Indies, the Dutch language has no official status there[76] and the small minority that can speak the language fluently are either educated members of the oldest generation, or employed in the legal profession such as historians, diplomats, lawyers, jurists and linguists/polyglots,[77] as certain law codes are still only available in Dutch.[78] Dutch is taught in various educational centres in Indonesia, the most important of which is the Erasmus Language Centre (ETC) in Jakarta. Each year, some 1,500 to 2,000 students take Dutch courses there.[79] In total, several thousand Indonesians study Dutch as a foreign language.[80] Owing to centuries of Dutch rule in Indonesia, many old documents are written in Dutch. Many universities therefore include Dutch as a source language, mainly for law and history students.[81] In Indonesia this involves about 35,000 students.[67]

Unlike other European nations, the Dutch chose not to follow a policy of language expansion amongst the indigenous peoples of their colonies.[82] In the last quarter of the 19th century, however, a local elite gained proficiency in Dutch so as to meet the needs of expanding bureaucracy and business.[83] Nevertheless, the Dutch government remained reluctant to teach Dutch on a large scale for fear of destabilising the colony. Dutch, the language of power, was supposed to remain in the hands of the leading elite.[83]

After independence, Dutch was dropped as an official language and replaced by Indonesian, but this does not mean that Dutch has completely disappeared in Indonesia, Indonesian Dutch, a regional variety of the Dutch, was still spoken by about 500,000 half-blood in Indonesia in 1985.[84] Yet the Indonesian language inherited many words from Dutch: words for everyday life as well as scientific and technological terms.[85] One scholar argues that 20% of Indonesian words can be traced back to Dutch words,[10] many of which are transliterated to reflect phonetic pronunciation e.g. kantoor "office" in Indonesian is kantor, handdoek "towel" in Indonesian is handuk, or bushalte "bus stop" in Indonesian is halte bus. In addition, many Indonesian words are calques of Dutch; for example, rumah sakit "hospital" is calqued on the Dutch ziekenhuis (literally "sickhouse"), kebun binatang "zoo" on dierentuin (literally "animal garden"), undang-undang dasar "constitution" from grondwet (literally "ground law"). These account for some of the differences in vocabulary between Indonesian and Malay. Some regional languages in Indonesia have some Dutch loanwords as well; for example, Sundanese word Katel or "frying pan" origin in Dutch is "ketel". The Javanese word for "bike/bicycle" "pit" can be traced back to its origin in Dutch "fiets". The Malacca state of Malaysia was also colonized by the Dutch in its longest period that Malacca was under foreign control. In the 19th century, the East Indies trade started to dwindle, and with it the importance of Malacca as a trading post. The Dutch state officially ceded Malacca to the British in 1825. It took until 1957 for Malaya to gain its independence.[86] Despite this, the Dutch language is rarely spoken in Malacca or Malaysia and only limited to foreign nationals able to speak the language.

After the declaration of independence of Indonesia, Western New Guinea, the "wild east" of the Dutch East Indies, remained a Dutch colony until 1962, known as Netherlands New Guinea.[87] Despite prolonged Dutch presence, the Dutch language is not spoken by many Papuans, the colony having been ceded to Indonesia in 1963.

Dutch-speaking immigrant communities can also be found in Australia and New Zealand. The 2011 Australian census showed 37,248 people speaking Dutch at home.[88] At the 2006 New Zealand census, 26,982 people, or 0.70 percent of the total population, reported to speak Dutch to sufficient fluency that they could hold an everyday conversation.[89]

In contrast to the colonies in the East Indies, from the second half of the 19th century onwards, the Netherlands envisaged the expansion of Dutch in its colonies in the West Indies. Until 1863, when slavery was abolished in the West Indies, slaves were forbidden to speak Dutch, with the effect that local creoles such as Papiamento and Sranan Tongo which were based not on Dutch but rather other European languages, became common in the Dutch West Indies. However, as most of the people in the Colony of Surinam (now Suriname) worked on Dutch plantations, this reinforced the use of Dutch as a means for direct communication.[83][90]

In Suriname today, Dutch is the sole official language,[91] and over 60 percent of the population speaks it as a mother tongue.[92] Dutch is the obligatory medium of instruction in schools in Suriname, even for non-native speakers.[93] A further twenty-four percent of the population speaks Dutch as a second language.[94] Suriname gained its independence from the Netherlands in 1975 and has been an associate member of the Dutch Language Union since 2004.[95] The lingua franca of Suriname, however, is Sranan Tongo,[96] spoken natively by about a fifth of the population.[68][m]

In Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao and Sint Maarten, all parts of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Dutch is the official language but spoken as a first language by only 7% to 8% of the population,[97] although most native-born people on the islands can speak the language since the education system is in Dutch at some or all levels.

In the United States, a now extinct dialect of Dutch, Jersey Dutch, spoken by descendants of 17th-century Dutch settlers in Bergen and Passaic counties, was still spoken as late as 1921.[98] Other Dutch-based creole languages once spoken in the Americas include Mohawk Dutch (in Albany, New York), Berbice (in Guyana), Skepi (in Essequibo, Guyana) and Negerhollands (in the United States Virgin Islands). Pennsylvania Dutch is not a member of the set of Dutch dialects and is less misleadingly called Pennsylvania German.[99]

Martin Van Buren, the eighth President of the United States, spoke Dutch natively and is the only U.S. president whose first language was not English. Dutch prevailed for many generations as the dominant language in parts of New York along the Hudson River. Another famous American born in this region who spoke Dutch as a first language was Sojourner Truth.

According to the 2000 United States census, 150,396 people spoke Dutch at home,[100] while according to the 2006 Canadian census, this number reaches 160,000 Dutch speakers.[101] At an academic level, 20 universities offer Dutch studies in the United States.[73][74] In Canada, Dutch is the fourth most spoken language by farmers, after English, French and German,[102] and the fifth most spoken non-official language overall (by 0.6% of Canadians).[103]

The largest legacy of the Dutch language lies in South Africa, which attracted large numbers of Dutch, Flemish and other northwest European farmer (in Dutch, boer) settlers, all of whom were quickly assimilated.[104] The long isolation from the rest of the Dutch-speaking world made the Dutch as spoken in Southern Africa evolve into what is now Afrikaans.[105] In 1876, the first Afrikaans newspaper called Die Afrikaanse Patriot was published in the Cape Colony.[106]

European Dutch remained the literary language[105] until the start of the 1920s, when under pressure of Afrikaner nationalism the local "African" Dutch was preferred over the written, European-based standard.[104] In 1925, section 137 of the 1909 constitution of the Union of South Africa was amended by Act 8 of 1925, stating "the word Dutch in article 137 ... is hereby declared to include Afrikaans".[107][108] The constitution of 1983 only listed English and Afrikaans as official languages. It is estimated that between 90% and 95% of Afrikaans vocabulary is ultimately of Dutch origin.[109][110]

Both languages are still largely mutually intelligible, although this relation can in some fields (such as lexicon, spelling and grammar) be asymmetric, as it is easier for Dutch speakers to understand written Afrikaans than it is for Afrikaans speakers to understand written Dutch.[111] Afrikaans is grammatically far less complex than Dutch, and vocabulary items are generally altered in a clearly patterned manner, e.g. vogel becomes voël ("bird") and regen becomes reën ("rain").[112] In South Africa, the number of students following Dutch at university is difficult to estimate, since the academic study of Afrikaans inevitably includes the study of Dutch.[67] Elsewhere in the world, the number of people learning Dutch is relatively small.

Afrikaans is the third largest language of South Africa in terms of native speakers (~13.5%),[113] of whom 53% are Coloureds and 42.4% Whites.[114] In 1996, 40 percent of South Africans reported to know Afrikaans at least at a very basic level of communication.[115] It is the lingua franca in Namibia,[104][116][117] where it is spoken natively in 11 percent of households.[118] In total, Afrikaans is the first language in South Africa alone of about 7.1 million people[113] and is estimated to be a second language for at least 10 million people worldwide,[119] compared to over 23 million[92] and 5 million respectively, for Dutch.[2]

The Dutch colonial presence elsewhere in Africa, notably Dutch Gold Coast, was too ephemeral not to be wiped out by prevailing colonising European successors. Belgian colonial presence in Congo and Rwanda-Urundi (Burundi and Rwanda, held under League of Nations mandate and later a UN trust territory) left little Dutch (Flemish) legacy, as French was the main colonial language.[120]

For further details on different realisations of phonemes, dialectal differences and example words, see the full article at Dutch phonology.

Unlike other Germanic languages, Dutch has no phonological aspiration of consonants.[121] Like most other Germanic languages, the Dutch consonant system did not undergo the High German consonant shift and has a syllable structure that allows fairly-complex consonant clusters. Dutch also retains full use of the velar fricatives of Proto-Germanic that were lost or modified in many other Germanic languages. Dutch has final-obstruent devoicing. At the end of a word, voicing distinction is neutralised and all obstruents are pronounced voiceless. For example, Dutch goede (̇'good') is [ˈɣudə] but the related form goed is [ɣut]. Dutch shares this final-obstruent devoicing with German (the Dutch noun goud is pronounced [ɣɑut], the adjective gouden is pronounced [ɣɑudə(n)], like the German noun Gold, pronounced [ɡɔlt], adjective golden, pronounced [ɡɔldn] vs English gold and golden, both pronounced with [d].)

Voicing of pre-vocalic initial voiceless alveolar fricatives occurs although less in Dutch than in German (Dutch zeven, German sieben with [z] versus English seven and Low German seven with [s]), and also the shift /θ/ → /d/. Dutch shares only with Low German the development of /xs/ → /ss/ (Dutch vossen, ossen and Low German Vösse, Ossen versus German Füchse, Ochsen and English foxes, oxen), and also the development of /ft/ → /xt/ though it is far more common in Dutch (Dutch zacht and Low German sacht versus German sanft and English soft, but Dutch kracht versus German Kraft and English craft).

Notes:

Like English, Dutch did not develop i-mutation as a morphological marker and shares with most other Germanic languages the lengthening of short vowels in stressed open syllables, which has led to contrastive vowel length being used as a morphological marker. Dutch has an extensive vowel inventory. Vowels can be grouped as back rounded, front unrounded and front rounded. They are also traditionally distinguished by length or tenseness.

Vowel length is not always considered a distinctive feature in Dutch phonology because it normally occurs with changes in vowel quality. One feature or the other may be considered redundant, and some phonemic analyses prefer to treat it as an opposition of tenseness. However, even if it is not considered part of the phonemic opposition, the long/tense vowels are still realised as phonetically longer than their short counterparts. The changes in vowel quality are also not always the same in all dialects, some of which may be little difference at all, with length remaining the primary distinguishing feature. Although all older words pair vowel length with a change in vowel quality, new loanwords have reintroduced phonemic oppositions of length. Compare zonne(n) [ˈzɔnə] ("suns") versus zone [ˈzɔːnə] ("zone") versus zonen [ˈzoːnə(n)] ("sons"), or kroes [krus] ("mug") versus cruise [kruːs] ("cruise").

Notes:

Unique to the development of Dutch is the collapse of older ol/ul/al + dental into ol + dental, followed by vocalisation of pre-consonantal /l/ and after a short vowel. That created the diphthong /ɑu/: Dutch goud, zout and bout corresponds with Low German Gold, Solt, Bolt; German Gold, Salz, Balt and English gold, salt, bolt. It is the most common diphthong, along with /ɛi œy/. All three are the only ones commonly considered unique phonemes in Dutch. The tendency for native English speakers is to pronounce Dutch names with /ɛi/ (written as ij or ei) as /aɪ/, (like the English "long i"), which does not normally lead to confusion for native listeners since in a number of dialects (such as in Amsterdam[123]), the same pronunciation is heard.

In contrast, /ɑi/ and /ɔi/ are rare in Dutch. The "long/tense" diphthongs are indeed realised as proper diphthongs but are generally analysed phonemically as a long/tense vowel, followed by a glide /j/ or /ʋ/. All diphthongs end in a close vowel (/i y u/) and are grouped here by their first element.

The syllable structure of Dutch is (C)(C)(C)V(C)(C)(C)(C). Many words, as in English, begin with three consonants: straat /straːt/ (street). There are words that end in four consonants: herfst /ɦɛrfst/ (autumn), ergst /ɛrxst/ (worst), interessantst /ɪn.tə.rɛ.sɑntst/ (most interesting), sterkst /stɛrkst/ (strongest), the last three of which are superlative adjectives.

The highest number of consonants in a single cluster is found in the word slechtstschrijvend /ˈslɛxtstˌsxrɛi̯vənt/ (writing worst), with seven consonant phonemes. angstschreeuw (scream in fear) has six in a row.

A notable change in pronunciation has been occurring in younger generations in the Dutch provinces of Utrecht, North and South Holland, which has been dubbed "Polder Dutch" by Jan Stroop.[124] Such speakers pronounce ⟨ij/ei⟩, ⟨ou/au⟩ and ⟨ui⟩, which used to be pronounced respectively as /ɛi/, /ɔu/, and /œy/, as increasingly lowered to [ai], [au], and [ay] respectively. In addition, the same speakers pronounce /eː/, /oː/, and /øː/ as the diphthongs [ei], [ou], and [øy][125] respectively, making the change an example of a chain shift.

The change is interesting from a sociolinguistic point of view because it has apparently happened relatively recently, in the 1970s and was pioneered by older well-educated women from the upper middle classes.[126] The lowering of the diphthongs has long been current in many Dutch dialects and is comparable to the English Great Vowel Shift and the diphthongisation of long high vowels in Modern High German, which had centuries earlier reached the state now found in Polder Dutch. Stroop theorises that the lowering of open-mid to open diphthongs is a phonetically "natural" and inevitable development and that Dutch, after it had diphthongised the long high vowels like German and English, "should" have lowered the diphthongs like German and English as well.

Instead, he argues that the development has been artificially frozen in an "intermediate" state by the standardisation of Dutch pronunciation in the 16th century in which lowered diphthongs found in rural dialects were perceived as ugly by the educated classes and were accordingly declared substandard. Now, however, he thinks that the newly-affluent and independent women can afford to let that natural development take place in their speech. Stroop compares the role of Polder Dutch with the urban variety of British English pronunciation called Estuary English.

Among Belgian and Surinamese Dutch-speakers and speakers from other regions in the Netherlands, this vowel shift is not taking place.

Dutch is grammatically similar to German, such as in syntax and verb morphology (for verb morphology in English verbs, Dutch and German, see Germanic weak verb and Germanic strong verb). Grammatical cases have largely become limited to pronouns and many set phrases. Inflected forms of the articles are often grace surnames and toponyms.

Standard Dutch uses three genders across natural and grammatical genders but for most non-Belgian speakers, masculine and feminine have merged to form the common gender (with de for "the"). The neuter (which uses het) remains distinct. This is similar to those of most Continental Scandinavian tongues. Less so than English, inflectional grammar (such as in adjectival and noun endings) has simplified.

When grouped according to their conjugational class, Dutch has four main verb types: weak verbs, strong verbs, irregular verbs and mixed verbs.

Weak verbs are most numerous, constituting about 60% of all verbs. In these, the past tense and past participle are formed with a dental suffix:

Strong verbs are the second most numerous verb group. This group is characterised by a vowel alternation of the stem in the past tense and perfect participle. Dutch distinguishes between 7 classes, comprising almost all strong verbs, with some internal variants. Dutch has many 'half strong verbs': these have a weak past tense and a strong participle or a strong past tense and a weak participle. The following table shows the vowel alternations in more detail. It also shows the number of roots (bare verbs) that belong to each class, variants with a prefix are excluded.

There is an ongoing process of "weakening" of strong verbs. The verb "ervaren" (to experience) used to be strictly a class 6 strong verb, having the past tense "ervoer" and participle "ervaren", but the weak form "ervaarde" for both past tense and participle is currently also in use. Some other verbs that were originally strong such as "raden" (to guess) and "stoten" (to bump), have past tense forms "ried" and "stiet" that are at present far less common than their weakened forms; "raadde" and "stootte".[127] In most examples of such weakened verbs that were originally strong, both their strong and weak formations are deemed correct.

As in English, the case system of Dutch and the subjunctive have largely fallen out of use, and the system has generalised the dative over the accusative case for certain pronouns (NL: me, je; EN: me, you; LI: mi, di vs. DE: mich/mir, dich/dir). While standard Dutch has three grammatical genders, this has few consequences and the masculine and feminine gender are usually merged into a common gender in the Netherlands but not in Belgium (EN: none; NL/LI: common and neuter; in Belgium masculine, feminine and neuter is in use).

Modern Dutch has mostly lost its case system.[128] However, certain idioms and expressions continue to include now archaic case declensions. The definite article has just two forms, de and het, more complex than English, which has only the. The use of the older inflected form den in the dative and accusative, as well as use of der in the dative, is restricted to numerous set phrases, surnames and toponyms. But some dialects still use both, particularly "der" is often used instead of "haar" (her).

In modern Dutch, the genitive articles des and der in the bottom line are commonly used in idioms. Other usage is typically considered archaic, poetic or stylistic. One must know whether a noun is masculine or feminine to use them correctly. In most circumstances, the preposition van, the middle line, is instead used, followed by the normal article de or het, and in that case it makes no difference whether a word is masculine or feminine. For the idiomatic use of the articles in the genitive, see for example:

In contemporary usage, the genitive case still occurs a little more often with plurals than with singulars, as the plural article is der for all genders and no special noun inflection must be taken account of. Der is commonly used in order to avoid reduplication of van, e.g. het merendeel der gedichten van de auteur instead of het merendeel van de gedichten van de auteur ("the bulk of the author's poems").

There is also a genitive form for the pronoun die/dat ("that [one], those [ones]"), namely diens for masculine and neuter singulars (occurrences of dier for feminine singular and all plurals are extremely rare). Although usually avoided in common speech, this form can be used instead of possessive pronouns to avoid confusion. Compare:

Analogically, the relative and interrogative pronoun wie ("who") has the genitive forms wiens and wier (corresponding to English whose, but less frequent in use).

Dutch also has a range of fixed expressions that make use of the genitive articles, which can be abbreviated using apostrophes. Common examples include "'s ochtends" (with 's as abbreviation of des; "in the morning") and desnoods (lit: "of the need", translated: "if necessary").

The Dutch written grammar has simplified over the past 100 years: cases are now mainly used for the pronouns, such as ik (I), mij, me (me), mijn (my), wie (who), wiens (whose: masculine or neuter singular), wier (whose: feminine singular; masculine, feminine or neuter plural). Nouns and adjectives are not case inflected (except for the genitive of proper nouns (names): -s, -'s or -'). In the spoken language cases and case inflections had already gradually disappeared from a much earlier date on (probably the 15th century) as in many continental West Germanic dialects.

Inflection of adjectives is more complicated. The adjective receives no ending with indefinite neuter nouns in singular (as with een /ən/ 'a/an'), and -e in all other cases. (This was also the case in Middle English, as in "a goode man".) Fiets belongs to the masculine/feminine category, while water and huis are neuter.

An adjective has no e if it is in the predicative: De soep is koud.

More complex inflection is still found in certain lexicalised expressions like de heer des huizes (literally, "the man of the house"), etc. These are usually remnants of cases (in this instance, the genitive case which is still used in German, cf. Der Herr des Hauses) and other inflections no longer in general use today. In such lexicalised expressions remnants of strong and weak nouns can be found too, e.g. in het jaar des Heren (Anno Domini), where -en is actually the genitive ending of the weak noun. Similarly in some place names: 's-Gravenbrakel, 's-Hertogenbosch, etc. (with weak genitives of graaf "count", hertog "duke"). Also in this case, German retains this feature.

Dutch shares much of its word order with German. Dutch exhibits subject–object–verb word order, but in main clauses the conjugated verb is moved into the second position in what is known as verb second or V2 word order. This makes Dutch word order almost identical to that of German, but often different from English, which has subject–verb–object word order and has since lost the V2 word order that existed in Old English.[129]

An example sentence used in some Dutch language courses and textbooks is "Ik kan mijn pen niet vinden omdat het veel te donker is", which translates into English word for word as "I can my pen not find because it far too dark is", but in standard English word order would be written "I cannot find my pen because it is far too dark". If the sentence is split into a main and subclause and the verbs highlighted, the logic behind the word order can be seen.

Main clause: "Ik kan mijn pen niet vinden"

Verb infinitives are placed in final position, but the finite, conjugated verb, in this case "kan" (can), is made the second element of the clause.

In subordinate clauses: "omdat het veel te donker is", the verb or verbs always go in the final position.

In an interrogative main clause the usual word order is: conjugated verb followed by subject; other verbs in final position:

In the Dutch equivalent of a wh-question the word order is: interrogative pronoun (or expression) + conjugated verb + subject; other verbs in final position:

In a tag question the word order is the same as in a declarative clause:

A subordinate clause does not change its word order:

In Dutch, the diminutive is used extensively. The nuances of meaning expressed by the diminutive are a distinctive aspect of Dutch, and can be difficult for non-native speakers to master. It is very productive[130]: 61 and formed by adding one of the suffixes to the noun in question, depending on the latter's phonological ending:

The diminutive suffixes -ke (from which -tje has derived by palatalisation), -eke, -ske, -ie (only for words ending -ch, -k, -p, or -s), -kie (instead of -kje), and -pie (instead of -pje) are used in southern dialects, and the forms ending on -ie as well in northern urban dialects. Some of these form part of expressions that became standard language, like een makkie, from gemak = ease). The noun joch (young boy) has, exceptionally, only the diminutive form jochie, also in standard Dutch. The form -ke is also found in many women's given names: Janneke, Marieke, Marijke, Mieke, Meike etc.

In Dutch, the diminutive is not restricted to nouns, but can be applied to numerals (met z'n tweetjes, "the two of us"), pronouns (onderonsje, "tête-à-tête"), verbal particles (moetje, "shotgun marriage"), and even prepositions (toetje, "dessert").[130]: 64–65 Adjectives and adverbs commonly take diminutive forms; the former take a diminutive ending and thus function as nouns, while the latter remain adverbs and always have the diminutive with the -s appended, e.g. adjective: groen ("green") → noun: groentje ("rookie"); adverb: even ("a while") → adverb: eventjes ("a little while").

Some nouns have two different diminutives, each with a different meaning: bloem (flower) → bloempje (lit. "small flower"), but bloemetje (lit. also "small flower", meaning bouquet). A few nouns exist solely in a diminutive form, e.g. zeepaardje (seahorse), while many, e.g. meisje (girl), originally a diminutive of meid (maid), have acquired a meaning independent of their non-diminutive forms. A diminutive can sometimes be added to an uncountable noun to refer to a single portion: ijs (ice, ice cream) → ijsje (ice cream treat, cone of ice cream), bier (beer) → biertje. Some diminutive forms only exist in the plural, e.g. kleertjes (clothing).

When used to refer to time, the Dutch diminutive form can indicate whether the person in question found it pleasant or not: een uurtjekletsen (chatting for a "little" hour.) The diminutive can, however, also be used pejoratively: Hij was weer eens het "mannetje". (He acted as if he was the "little" man.)

All diminutives (even lexicalised ones like "meisje" (girl)) have neuter gender and take neuter concords: "dit kleine meisje", not "deze kleine meisje".

There are two series of personal pronouns, subject and objects pronouns. The forms on the right-hand sides within each column are the unemphatic forms; those not normally written are given in brackets. Only ons and u do not have an unemphatic form. The distinction between emphatic and unemphatic pronouns is very important in Dutch.[130]: 67 Emphatic pronouns in English use the reflexive pronoun form, but are used to emphasise the subject, not to indicate a direct or indirect object. For example, "I gave (to) myself the money" is reflexive but "I myself gave the money (to someone else) " is emphatic.

Like English, Dutch has generalised the dative over the accusative case for all pronouns, e.g. NL 'me', 'je', EN 'me', 'you', vs. DE 'mich'/'mir' 'dich'/'dir'. There is one exception: the standard language prescribes that in the third person plural, hen is to be used for the direct object, and hun for the indirect object. This distinction was artificially introduced in the 17th century by grammarians, and is largely ignored in spoken language and not well understood by Dutch speakers. Consequently, the third person plural forms hun and hen are interchangeable in normal usage, with hun being more common. The shared unstressed form ze is also often used as both direct and indirect objects and is a useful avoidance strategy when people are unsure which form to use.[131]

Dutch also shares with English the presence of h- pronouns, e.g. NL hij, hem, haar, hen, hun and EN he, him, her vs. DE er, ihn, ihr, ihnen.

Like most Germanic languages, Dutch forms noun compounds, where the first noun modifies the category given by the second (hondenhok = doghouse). Unlike English, where newer compounds or combinations of longer nouns are often written in open form with separating spaces, Dutch (like the other Germanic languages) either uses the closed form without spaces (boomhut = tree house) or inserts a hyphen (VVD-coryfee = outstanding member of the VVD, a political party). Like German, Dutch allows arbitrarily long compounds, but the longer they get, the less frequent they tend to be.

The longest serious entry in the Van Dale dictionary is (ceasefire negotiation). Leafing through the articles of association (Statuten) one may come across a 30-letter (authorisation of representation). An even longer word cropping up in official documents is (health insurance company) though the shorter zorgverzekeraar (health insurer) is more common.

Notwithstanding official spelling rules, some Dutch-speaking people, like some Scandinavians and German speakers, nowadays tend to write the parts of a compound separately, a practice sometimes dubbed de Engelse ziekte (the English disease).[132]

Dutch vocabulary is predominantly Germanic in origin, with loanwords accounting for 20%.[133] The main foreign influence on Dutch vocabulary since the 12th century and culminating in the French period has been French and (northern) Oïl languages, accounting for an estimated 6.8% of all words, or more than a third of all loanwords. Latin, which was spoken in the southern Low Countries for centuries and then played a major role as the language of science and religion, follows with 6.1%. High German and Low German were influential until the mid-20th century and account for 2.7%, but they are mostly unrecognisable since many have been "Dutchified": German Fremdling → Dutch vreemdeling. Dutch has borrowed words from English since the mid-19th century, as a consequence of the increasing power and influence of Britain and the United States. English loanwords are about 1.5%, but continue to increase.[134] Many English loanwords become less visible over time as they are either gradually replaced by calques (skyscraper became Dutch wolkenkrabber) or neologisms (bucket list became loodjeslijst). Conversely, Dutch contributed many loanwords to English, accounting for 1.3% of its lexicon.[135]

The main Dutch dictionary is the Van Dale groot woordenboek der Nederlandse taal, which contains some 268,826 headwords.[136] In the field of linguistics, the 45,000-page Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal is also widely used. That scholarly endeavour took 147 years to complete and contains all recorded Dutch words from the Early Middle Ages onward.

Dutch is written using the Latin script. Dutch uses one additional character beyond the standard alphabet, the digraph ⟨ij⟩. It has a relatively high proportion of doubled letters, both vowels and consonants, due to the formation of compound words and also to the spelling devices for distinguishing the many vowel sounds in the Dutch language. An example of five consecutive doubled letters is the word voorraaddoos (food storage container). The diaeresis (Dutch: trema) is used to mark vowels that are pronounced separately when involving a pre- or suffix, and a hyphen is used when the problem occurs in compound words, e.g beïnvloed (influenced), de zeeën (the seas) but zee-eend (scoter; lit. sea duck). Generally, other diacritical marks occur only in loanwords. However, the acute accent can also be used for emphasis or to differentiate between two forms, and its most common use is to differentiate between the indefinite article een /ən/ "a, an" and the numeral één /eːn/ "one".

Since the 1980s, the Dutch Language Union has been given the mandate to review and make recommendations on the official spelling of Dutch. Spelling reforms undertaken by the union occurred in 1995 and 2005. In the Netherlands, the official spelling is currently given legal basis by the Spelling Act of September 15, 2005.[n][o] The Spelling Act gives the Committee of Ministers of the Dutch Language Union the authority to determine the spelling of Dutch by ministerial decision. In addition, the law requires that this spelling be followed "at the governmental bodies, at educational institutions funded from the public purse, as well as at the exams for which legal requirements have been established". In other cases, it is recommended, but it is not mandatory to follow the official spelling. The Decree on the Spelling Regulations 2005 of 2006 contains the annexed spelling rules decided by the Committee of Ministers on April 25, 2005.[p][q] In Flanders, the same spelling rules are currently applied by the Decree of the Flemish Government Establishing the Rules of the Official Spelling and Grammar of the Dutch language of June 30, 2006.[r]

The Woordenlijst Nederlandse taal, more commonly known as het groene boekje (i.e. "the green booklet", because of its colour), is the authoritative orthographic word list (without definitions) of the Dutch Language Union; a version with definitions can be had as Het Groene Woordenboek; both are published by Sdu.

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Dutch:

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in English:

The official languages of the Union of South American Nations will be English, Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch.