Лейпциг ( / ˈl aɪp sɪɡ , -sɪx / LYPE -sig , -sikh , [4] [ 5] [6] [ 7] Немецкий : [ ˈlaɪptsɪç ] ;верхнесаксонский:Leibz'sch;верхнесаксонский:Lipsk) — самый густонаселенный город в немецкойземлеСаксония.По состоянию на 2023 год в городе проживает 628 718 жителей.[8]Этовосьмой по величине городв Германии, входит вСреднегерманский столичный регион. Название города обычно интерпретируется как славянский термин, означающийместолип, в соответствии со многими другими славянскими топонимами в регионе.[9]

Лейпциг расположен примерно в 150 км (90 миль) к юго-западу от Берлина, в самой южной части Северо -Германской равнины ( Лейпцигский залив ), в месте слияния Белого Эльстера и его притоков Пляйссе и Парте , которые образуют обширную внутреннюю дельту в городе, известную как Лейпцигские Гевессеркнотен , вдоль которой развился Лейпцигский прибрежный лес , крупнейший в Европе внутригородской прибрежный лес . Лейпциг находится в центре Нойзеенланда ( нового озерного края ), состоящего из нескольких искусственных озер, созданных из бывших карьеров по добыче лигнита .

Лейпциг был торговым городом по крайней мере со времен Священной Римской империи . [10] Город находится на пересечении Via Regia и Via Imperii , двух важных средневековых торговых путей. Лейпцигская ярмарка датируется 1190 годом. Между 1764 и 1945 годами город был центром издательского дела. [11] После Второй мировой войны и в период Германской Демократической Республики (Восточной Германии) Лейпциг оставался крупным городским центром в Восточной Германии, но его культурное и экономическое значение снизилось. [11]

События в Лейпциге в 1989 году сыграли значительную роль в ускорении падения коммунизма в Центральной и Восточной Европе, в основном через демонстрации, начавшиеся у церкви Святого Николая . Непосредственные последствия воссоединения Германии включали крах местной экономики (которая стала зависеть от сильно загрязняющей окружающую среду тяжелой промышленности ), серьезную безработицу и упадок городов. К началу 2000-х годов тенденция изменилась, и с тех пор Лейпциг претерпел некоторые значительные изменения, включая городское и экономическое возрождение и модернизацию транспортной инфраструктуры. [12] [13]

В Лейпциге находится один из старейших университетов Европы ( Лейпцигский университет ). Это главное местонахождение Немецкой национальной библиотеки (второе место занимает Франкфурт ), Немецкого музыкального архива , а также Немецкого федерального административного суда . Лейпцигский зоопарк является одним из самых современных зоопарков в Европе и по состоянию на 2018 год занимает первое место в Германии и второе место в Европе. [14]

Архитектура Лейпцига конца XIX века в стиле грюндерства состоит из около 12 500 зданий. [15] [16] Центральный железнодорожный вокзал города Leipzig Hauptbahnhof , площадью 83 460 квадратных метров (898 400 квадратных футов), является крупнейшей железнодорожной станцией в Европе по площади пола. С тех пор как в 2013 году был введен в эксплуатацию Лейпцигский городской туннель , он стал центральным элементом системы общественного транспорта S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland ( S-Bahn Central Germany ), крупнейшей сети S-Bahn в Германии, с длиной системы 802 км (498 миль). [17]

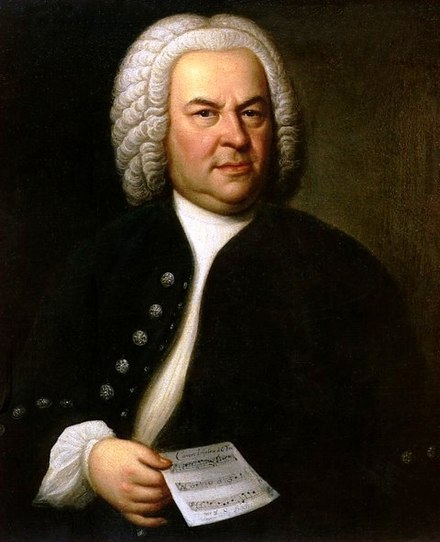

Лейпциг долгое время был крупным центром музыки, включая классическую и современную dark wave . Thomanerchor (английский: хор Св. Фомы Лейпцига), хор мальчиков, был основан в 1212 году. Лейпцигский оркестр Гевандхаус , основанный в 1743 году, является одним из старейших симфонических оркестров в мире. Несколько известных композиторов жили и работали в Лейпциге, в том числе Иоганн Себастьян Бах (1723-1750) и Феликс Мендельсон (1835-1847). Университет музыки и театра «Феликс Мендельсон-Бартольди» был основан в 1843 году. Oper Leipzig , один из самых известных оперных театров в Германии, был основан в 1693 году. Во время пребывания в Голисе , который сейчас является частью города, Фридрих Шиллер написал свою поэму « Ода к радости ».

Более раннее написание Лейпцига на английском языке — Leipsic . Также использовалось латинское название Lipsia . [18]

Название Лейпциг обычно считается производным от слова lipa , общеславянского обозначения лип , что делает название города этимологически связанным с Липецком, Россия и Лиепаей, Латвия . На основе средневековых свидетельств, таких как Lipzk (ок. 1190 г.), первоначальное славянское название города было реконструировано как *Lipьsko , которое также отражено в похожих формах в соседних современных славянских языках (лужицкое/польское Lipsk , чешское Lipsko ). Это, однако, было подвергнуто сомнению более поздними ономастическим исследованием, основанным на самых древних формах, таких как Libzi (ок. 1015 г.). [19]

В связи с этимологией, упомянутой выше, Lindenstadt или Stadt der Linden (Город лип) являются распространенными поэтическими эпитетами для города. [20]

Другой, несколько старомодный эпитет — Pleiß-Athen ( Афины на реке Плейссе ), намекающий на давнюю академическую и литературную традицию Лейпцига как места расположения одного из старейших немецких университетов и центра книжной торговли. [21]

Его также называют « Маленьким Парижем » ( Klein-Paris ) в честь « Фауста I» Иоганна Вольфганга Гёте , действие которого частично происходит в знаменитом лейпцигском ресторане Auerbachs Keller .

В 1937 году нацистское правительство официально переименовало город в Reichsmessestadt Leipzig (город имперской ярмарки Лейпциг). [22]

В 1989 году Лейпциг был назван Городом-героем ( Хельденштадт ), намекая на почетное звание, присуждаемое в бывшем Советском Союзе некоторым городам, сыгравшим ключевую роль в победе союзников во Второй мировой войне, в знак признания роли, которую понедельничные демонстрации сыграли в падении восточногерманского режима. [23]

В последнее время город иногда называют Hypezig , «Городом процветания Восточной Германии» или «Лучшим Берлином» ( Das bessere Berlin ), а СМИ отмечают его как модный городской центр за его яркий образ жизни и творческую среду со множеством стартапов . [24] [25] [26] [27]

Лейпциг расположен в Лейпцигском заливе , самой южной части Северо-Германской равнины , которая является частью Северо-Европейской равнины в Германии. Город расположен на Белом Эльстере , реке, которая берет начало в Чешской Республике и впадает в Заале к югу от Галле. Пляйссе и Парте соединяются с Белым Эльстером в Лейпциге, и большой внутренний дельтообразный ландшафт, который образуют три реки, называется Лейпцигскими Гевессеркнотенами . Для этого места характерны болотистые районы, такие как Лейпцигский прибрежный лес ( Leipziger Auenwald ), хотя к северу от города есть также некоторые известняковые районы. Ландшафт в основном плоский, хотя есть также некоторые свидетельства наличия морены и друмлинов .

Хотя в черте города есть несколько лесных парков, окрестности Лейпцига относительно безлесны. В 20 веке в регионе было несколько карьеров, многие из которых были преобразованы в озера. [28] См. также: Нойзеенланд

Лейпциг также расположен на пересечении древних дорог, известных как Via Regia (Королевская дорога), которая пересекала Германию с востока на запад, и Via Imperii (Императорская дорога), дорога, пролегающая с севера на юг.

В Средние века Лейпциг был городом-крепостью, а нынешняя «кольцевая» дорога вокруг исторического центра города проходит по линии старых городских стен.

С 1992 года Лейпциг был административно разделен на десять Stadtbezirke (городских округов), которые в свою очередь включают в себя в общей сложности 63 Ortsteile (местности). Некоторые из них соответствуют отдаленным деревням, которые были присоединены к Лейпцигу.

Как и во многих городах Восточной Германии, в Лейпциге преобладает океанический климат ( Кеппен : Cfb ), со значительным континентальным влиянием из-за его внутреннего расположения. Зимы холодные, со средней температурой около 1 °C (34 °F). Лето, как правило, теплое, со средней температурой 19 °C (66 °F) с дневной температурой 24 °C (75 °F). Осадков зимой примерно вдвое меньше, чем летом. Количество солнечного сияния значительно различается между зимой и летом, в среднем около 51 часа солнечного сияния в декабре (1,7 часа в день) по сравнению с 229 часами солнечного сияния в июле (7,4 часа в день). [32]

Лейпциг впервые упоминается в 1015 году в хрониках епископа Титмара Мерзебургского как urbs Libzi ( Chronicon , VII, 25) и наделен городскими и рыночными привилегиями в 1165 году Оттоном Богатым . Лейпцигская ярмарка , начавшаяся в Средние века , стала событием международного значения и является старейшей сохранившейся торговой ярмаркой в мире. Это способствовало росту лейпцигской торговой буржуазии .

Имеются записи о коммерческой рыболовной деятельности на реке Пляйссе , которые, скорее всего, относятся к Лейпцигу и датируются 1305 годом, когда маркграф Дитрих Младший предоставил права на рыболовство церкви и монастырю Святого Фомы. [35]

В городе и его окрестностях находилось несколько монастырей , в том числе францисканский монастырь, в честь которого названа Барфуссгесхен (Босая аллея), и монастырь ирландских монахов ( Якобскирхе , разрушенный в 1544 году) недалеко от нынешней улицы Ранштедтер Штайнвег (старая Виа Регия ).

Лейпцигский университет был основан в 1409 году, а Лейпциг превратился в важный центр немецкого права и издательского дела в Германии, в результате чего в XIX и XX веках здесь располагались Имперский суд и Немецкая национальная библиотека .

Во время Тридцатилетней войны в Брайтенфельде , примерно в 8 км (5 милях) от городских стен Лейпцига, произошло два сражения . Первое сражение при Брайтенфельде состоялось в 1631 году, а второе — в 1642 году. Оба сражения закончились победами шведской стороны.

24 декабря 1701 года, когда мэром был Франц Конрад Романус , была введена система уличного освещения на масляном топливе . Город нанял охранников, которые должны были следовать определенному графику, чтобы обеспечить пунктуальное зажигание 700 фонарей.

Район Лейпцига был ареной битвы при Лейпциге 1813 года между наполеоновской Францией и союзной коалицией Пруссии , России , Австрии и Швеции. Это было крупнейшее сражение в Европе до Первой мировой войны , и победа коалиции положила конец присутствию Наполеона в Германии и в конечном итоге привела к его первой ссылке на Эльбу . Памятник Битве Наций , отмечающий столетие этого события, был завершен в 1913 году. Помимо стимулирования немецкого национализма, война оказала большое влияние на мобилизацию гражданского духа в многочисленных добровольческих мероприятиях. Было сформировано множество добровольческих ополчений и гражданских ассоциаций, которые сотрудничали с церквями и прессой для поддержки местных и государственных ополчений, патриотической военной мобилизации, гуманитарной помощи и послевоенных памятных практик и ритуалов. [36]

Когда в 1839 году он стал конечной станцией первой немецкой железной дороги дальнего следования в Дрезден (столицу Саксонии), Лейпциг стал узлом центральноевропейского железнодорожного движения, а Leipzig Hauptbahnhof стал крупнейшей по площади конечной станцией в Европе. На железнодорожной станции есть два больших вестибюля: восточный для Королевских Саксонских государственных железных дорог и западный для Прусских государственных железных дорог .

В 19 веке Лейпциг был центром немецких и саксонских либеральных движений. [37] Первая немецкая рабочая партия , Всеобщее немецкое рабочее объединение ( Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein , ADAV) была основана в Лейпциге 23 мая 1863 года Фердинандом Лассалем ; около 600 рабочих со всей Германии отправились на строительство новой железной дороги. Лейпциг быстро разросся до более чем 700 000 жителей. Были построены огромные районы Gründerzeit , которые в основном пережили и войну, и послевоенный снос.

С открытием пятого производственного цеха в 1907 году Leipziger Baumwollspinnerei стала крупнейшей хлопкопрядильной компанией на континенте, имея более 240 000 веретен. Годовой объем производства превысил 5 миллионов килограммов пряжи. [38]

Во время Первой мировой войны , в 1917 году, американское консульство было закрыто, а его здание стало временным местом пребывания для американцев и беженцев- союзников из Сербии , Румынии и Японии . [39]

В 1930-х и 1940-х годах музыка была популярна во всем Лейпциге. Многие студенты посещали Музыкально-театральный колледж имени Феликса Мендельсона Бартольди (тогда он назывался Landeskonservatorium). Однако в 1944 году он был закрыт из-за Второй мировой войны . Он вновь открылся вскоре после окончания войны в 1945 году.

22 мая 1930 года Карл Фридрих Герделер был избран мэром Лейпцига. Позже он стал противником нацистского режима . [40] Он ушел в отставку в 1937 году, когда в его отсутствие его нацистский заместитель приказал разрушить городскую статую Феликса Мендельсона . В Хрустальную ночь в 1938 году была преднамеренно разрушена Лейпцигская синагога мавританского возрождения 1855 года , одно из самых архитектурно значимых зданий города. Герделер был позже казнен нацистами 2 февраля 1945 года.

Во время Второй мировой войны в Лейпциге на принудительных работах находилось несколько тысяч человек.

Начиная с 1933 года многие еврейские граждане Лейпцига были членами Gemeinde , большой еврейской религиозной общины, распространенной по всей Германии, Австрии и Швейцарии. В октябре 1935 года Gemeinde помогла основать Lehrhaus (на английском языке: дом обучения) в Лейпциге, чтобы предоставить различные формы обучения еврейским студентам, которым было запрещено посещать какие-либо учреждения в Германии. Особое внимание уделялось еврейским исследованиям, и большая часть еврейской общины Лейпцига была вовлечена в это. [41]

Как и все другие города, на которые претендовали нацисты, Лейпциг подвергся арианизации . Начиная с 1933 года и усиливаясь в 1939 году, еврейские владельцы бизнеса были вынуждены отказаться от своего имущества и магазинов. В конечном итоге это усилилось до такой степени, что нацистские чиновники стали достаточно сильны, чтобы выселить евреев из их собственных домов. Они также имели власть заставить многих евреев, живущих в городе, продать свои дома. Многие люди, продавшие свои дома, эмигрировали в другие места, за пределы Лейпцига. Другие переехали в Judenhäuser, которые были небольшими домами, которые действовали как гетто, в которых размещались большие группы людей. [41]

Евреи Лейпцига сильно пострадали от Нюрнбергских законов . Однако из-за Лейпцигской ярмарки и международного внимания, которое она привлекла, Лейпциг был особенно осторожен в отношении своего общественного имиджа. Несмотря на это, власти Лейпцига не боялись строго применять и обеспечивать соблюдение антисемитских мер. [41]

20 декабря 1937 года, после того как нацисты взяли город под свой контроль, они переименовали его в Reichsmessestadt Leipzig, что означает «Императорский ярмарочный город Лейпциг». [22] В начале 1938 года в Лейпциге наблюдался рост сионизма через еврейских граждан. Многие из этих сионистов пытались бежать до начала депортаций. [41] 28 октября 1938 года Генрих Гиммлер приказал депортировать польских евреев из Лейпцига в Польшу. [41] [42] Польское консульство укрыло 1300 польских евреев, предотвратив их депортацию. [43]

9 ноября 1938 года, в рамках Хрустальной ночи , на Готтшедштрассе были подожжены синагоги и предприятия. [41] Всего пару дней спустя, 11 ноября 1938 года, многие евреи из района Лейпцига были депортированы в концентрационный лагерь Бухенвальд. [44] Когда Вторая мировая война подошла к концу, большая часть Лейпцига была разрушена. После войны Коммунистическая партия Германии оказала помощь в восстановлении города. [45]

В 1933 году перепись зафиксировала, что в Лейпциге проживало более 11 000 евреев. В переписи 1939 года их число сократилось примерно до 4 500, а к январю 1942 года осталось всего 2 000. В том же месяце эти 2 000 евреев начали депортировать. [41] 13 июля 1942 года 170 евреев были депортированы из Лейпцига в концентрационный лагерь Освенцим . 19 сентября 1942 года 440 евреев были депортированы из Лейпцига в концентрационный лагерь Терезиенштадт . 18 июня 1943 года оставшиеся 18 евреев, все еще находившиеся в Лейпциге, были депортированы из Лейпцига в Освенцим. Согласно записям двух волн депортаций в Освенцим, выживших не было. Согласно записям о депортации из Терезиенштадта, выжило только 53 еврея. [41] [46]

Во время немецкого вторжения в Польшу в начале Второй мировой войны , в сентябре 1939 года, гестапо провело аресты видных местных поляков , [47] а также захватило польское консульство и его библиотеку. [43] В 1941 году американское консульство также было закрыто по приказу немецких властей. [39] Во время войны в Лейпциге располагалось пять вспомогательных лагерей концлагеря Бухенвальд , в которых содержалось более 8000 мужчин, женщин и детей, в основном поляков, евреев, советских и французских, но также итальянцев, чехов и бельгийцев. [48] В апреле 1945 года большинство выживших заключенных были отправлены на марши смерти в различные пункты назначения в Саксонии и оккупированной немцами Чехословакии , в то время как заключенные подлагеря Лейпциг-Текла, которые не могли маршировать, были сожжены заживо, расстреляны или забиты до смерти гестапо, СС , фольксштурмом и немецкими гражданскими лицами во время резни в Абтнаундорфе. [49] [50] Некоторые были спасены польскими подневольными рабочими другого лагеря; по крайней мере 67 человек выжили. [49] [50] 84 жертвы были похоронены 27 апреля 1945 года, однако общее число жертв остается неизвестным. [49] [50]

Во время Второй мировой войны Лейпциг неоднократно подвергался бомбардировкам союзников , начиная с 1943 года и продолжаясь до 1945 года. Первый налет произошел утром 4 декабря 1943 года, когда 442 бомбардировщика Королевских ВВС (RAF) сбросили на город в общей сложности почти 1400 тонн взрывчатых веществ и зажигательных веществ, уничтожив большую часть центра города. [51] Эта бомбардировка была крупнейшей на тот момент. Из-за непосредственной близости многих пострадавших зданий возник огненный шторм. Это побудило пожарных броситься в город; однако они не смогли контролировать пожары. В отличие от бомбардировки соседнего города Дрездена , это была в основном обычная бомбардировка с использованием взрывчатых веществ, а не зажигательных веществ. В результате потери были лоскутными, а не полной потерей его центра, но тем не менее были обширными.

Наземное наступление союзников в Германии достигло Лейпцига в конце апреля 1945 года. 2-я пехотная дивизия США и 69-я пехотная дивизия США пробились в город 18 апреля и завершили его взятие после ожесточенных городских боев, в которых бои часто велись за каждый дом и квартал, 19 апреля 1945 года. [52] В апреле 1945 года мэр Лейпцига, группенфюрер СС Альфред Фрейберг , его жена и дочь, а также заместитель мэра и городской казначей Эрнест Курт Лиссо, его жена, дочь и майор фольксштурма и бывший мэр Вальтер Дёнике покончили жизнь самоубийством в ратуше Лейпцига.

Соединенные Штаты передали город Красной Армии , когда она отступила от линии соприкосновения с советскими войсками в июле 1945 года к обозначенным границам зоны оккупации. Лейпциг стал одним из крупнейших городов Германской Демократической Республики ( Восточной Германии ).

После окончания Второй мировой войны в 1945 году в Лейпциге началось медленное возвращение евреев в город. [41] [53] К ним присоединилось большое количество немецких беженцев, которые были изгнаны из Центральной и Восточной Европы в соответствии с Потсдамским соглашением . [54]

В середине 20-го века городская ярмарка вновь обрела значение точки контакта с экономическим блоком СЭВ -Восточная Европа, членом которого была Восточная Германия . В это время ярмарки проводились на площадке на юге города, недалеко от Памятника битве народов .

Однако плановая экономика Германской Демократической Республики не была благосклонна к Лейпцигу. До Второй мировой войны в Лейпциге развивалась смесь промышленности, творческого бизнеса (особенно издательского дела) и услуг (включая юридические услуги). В период Германской Демократической Республики услуги стали заботой государства, сосредоточенной в Восточном Берлине ; творческий бизнес переместился в Западную Германию ; и в Лейпциге осталась только тяжелая промышленность. Что еще хуже, эта промышленность была чрезвычайно загрязняющей, что делало Лейпциг еще менее привлекательным городом для жизни. [55] Между 1950 годом и концом Германской Демократической Республики население Лейпцига сократилось с 600 000 до 500 000. [13]

В октябре 1989 года после молитв о мире в церкви Св. Николая , основанной в 1983 году как часть движения за мир, начались понедельничные демонстрации как самый заметный массовый протест против правительства Восточной Германии . [56] [57] Однако воссоединение Германии поначалу не пошло Лейпцигу на пользу. Централизованно планируемая тяжелая промышленность, которая стала специализацией города, оказалась, с точки зрения развитой экономики воссоединенной Германии, почти полностью нежизнеспособной и закрылась. Всего за шесть лет 90% рабочих мест в промышленности исчезли. [13] Поскольку безработица резко возросла, население резко сократилось; около 100 000 человек покинули Лейпциг за десять лет после воссоединения, а пустующее и заброшенное жилье стало острой проблемой. [13]

Начиная с 2000 года, амбициозный план городского обновления сначала остановил убыль населения Лейпцига, а затем обратил ее вспять. План был сосредоточен на сохранении и улучшении привлекательного исторического центра города и, в частности, его фонда зданий начала 20 века, а также на привлечении новых отраслей промышленности, частично за счет улучшения инфраструктуры. Однако обновление привело к джентрификации частей города и не остановило упадок Лейпцига-Востока. [55] [13]

Лейпциг является важным экономическим центром Германии. С 2010-х годов город был отмечен средствами массовой информации как модный городской центр с очень высоким качеством жизни. [58] [59] [60] Его часто называют «новым Берлином». [61] Лейпциг также является самым быстрорастущим городом Германии. [62] Лейпциг был немецким кандидатом на проведение летних Олимпийских игр 2012 года , но не прошел. После десяти лет строительства 14 декабря 2013 года открылся Лейпцигский городской тоннель . [63] Лейпциг является центральным элементом системы общественного транспорта S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland , которая действует в четырех немецких землях: Саксонии , Саксонии-Анхальт, Тюрингии и Бранденбурге .

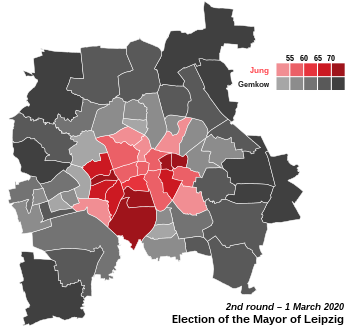

Первым свободно избранным мэром после объединения Германии стал Хинрих Леманн-Грубе из Социал-демократической партии (СДПГ), который занимал этот пост с 1990 по 1998 год. Первоначально мэр избирался городским советом, но с 1994 года избирается напрямую. Вольфганг Тифензее , также из СДПГ, занимал этот пост с 1998 года до своей отставки в 2005 году, чтобы стать федеральным министром транспорта. Его сменил коллега-политик СДПГ Буркхард Юнг , избранный в январе 2006 года и переизбранный в 2013 и 2020 годах. Последние выборы мэра состоялись 2 февраля 2020 года, а второй тур — 1 марта, и результаты были следующими:

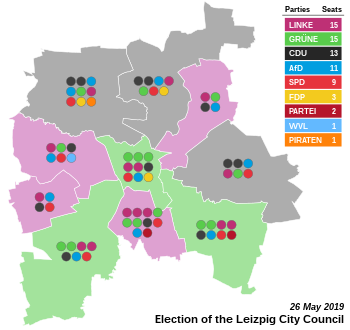

Последние выборы в городской совет состоялись 26 мая 2019 года, и результаты были следующими:

Лейпциг представлен в Бундестаге тремя избирательными округами : Лейпциг I , Лейпциг II и Лейпциг-Ланд .

_11_ies.jpg/440px-Leipzig_(Rathausturm,_Neues_Rathaus)_11_ies.jpg)

Население Лейпцига составляет около 620 000 человек. [65] В 1930 году население достигло своего исторического пика в более чем 700 000 человек. Оно неуклонно снижалось с 1950 года до примерно 530 000 человек в 1989 году. В 1990-х годах население довольно быстро сократилось до 437 000 человек в 1998 году. Это сокращение было в основном из-за внешней миграции и субурбанизации. После почти удвоения площади города за счет включения близлежащих городов в 1999 году число стабилизировалось и снова начало расти, увеличившись на 1000 человек в 2000 году. [66] По состоянию на 2015 год [update]Лейпциг является самым быстрорастущим городом в Германии с более чем 500 000 жителей. [67] Рост за последние 10–15 лет в основном был обусловлен внутренней миграцией. В последние годы внутренняя миграция ускорилась, достигнув в 2014 году 12 917 человек. [68]

В годы после объединения Германии многие люди трудоспособного возраста воспользовались возможностью переехать в земли бывшей Западной Германии в поисках работы. Это стало фактором, способствовавшим падению рождаемости. Рождаемость снизилась с 7000 в 1988 году до менее 3000 в 1994 году. [69] Однако число детей, родившихся в Лейпциге, возросло с конца 1990-х годов. В 2011 году оно достигло 5490 рождений, что привело к RNI в −17,7 (−393,7 в 1995 году). [70]

Уровень безработицы снизился с 18,2% в 2003 году до 9,8% в 2014 году и 7,6% в июне 2017 года. [71] [72] [73]

Процент населения с иммигрантским прошлым низок по сравнению с другими немецкими городами. По состоянию на 2012 год [update], только 5,6% населения были иностранцами, по сравнению со средним показателем по Германии в 7,7%. [74]

Число людей с иммигрантским прошлым (иммигранты и их дети) выросло с 49 323 в 2012 году до 77 559 в 2016 году, что составляет 13,3% населения города (население Лейпцига в 2016 году составляло 579 530 человек). [75]

Крупнейшие меньшинства (первое и второе поколение) в Лейпциге по стране происхождения по состоянию на 31 декабря 2021 года: [76]

В 2010-х годах Лейпциг часто называли Hypezig , поскольку проводились раздутые сравнения с Берлином 1990-х и начала 2000-х годов. Доступность, разнообразие и открытость города привлекли множество молодых людей со всей Европы, что привело к созданию альтернативной атмосферы, задающей тренды, что привело к инновационной музыкальной, танцевальной и художественной сцене. [77]

Исторический центр Лейпцига представляет собой ансамбль зданий в стиле Ренессанса шестнадцатого века, включая старую ратушу на рыночной площади. Также есть несколько торговых домов в стиле барокко и бывших резиденций богатых купцов. Поскольку Лейпциг значительно вырос во время экономического бума конца девятнадцатого века, в городе много зданий в историческом стиле, представляющих эпоху грюндерства . Примерно 35% квартир Лейпцига находятся в зданиях этого типа. Новая ратуша , завершенная в 1905 году, построена в том же стиле.

Около 90 000 квартир в Лейпциге были построены в зданиях Plattenbau во время коммунистического правления в Восточной Германии. [78] И хотя некоторые из них были снесены, а число людей, живущих в этом типе жилья, сократилось в последние годы, значительное меньшинство людей все еще живет в жилье Plattenbau; например, в Грюнау в 2016 году в таком жилье проживало около 43 600 человек. [79]

Церковь Святого Павла была разрушена коммунистическим правительством в 1968 году, чтобы освободить место для нового главного здания университета. После некоторых дебатов город решил построить новое, в основном светское здание на том же месте, названное Paulinum , которое было завершено в 2012 году. Его архитектура намекает на облик бывшей церкви и включает в себя пространство для религиозного использования факультетом теологии, включая оригинальный алтарь из старой церкви и два новых органа.

Многие коммерческие здания были построены в 1990-х годах в результате налоговых льгот после объединения Германии.

Самое высокое сооружение в Лейпциге — это дымоход Stahl- und Hartgusswerk Bösdorf GmbH высотой 205 м (673 фута). Самым высоким зданием в Лейпциге является City -Hochhaus Leipzig высотой 142 м (466 футов) . С 1972 по 1973 год это было самое высокое здание в Германии .

Одним из самых ярких событий современного искусства города стала ретроспектива Нео Рауха , которая открылась в апреле 2010 года в Лейпцигском музее изящных искусств . Это выставка, посвященная отцу Новой Лейпцигской школы [80] художников. Согласно The New York Times , [81] эта сцена «была тостом мира современного искусства» в течение последнего десятилетия. Кроме того, в так называемом Spinnerei есть одиннадцать галерей . [82]

В комплексе музея Грасси находятся еще три крупных коллекции Лейпцига: [83] Этнографический музей , Музей прикладного искусства и Музей музыкальных инструментов (последний из которых находится в ведении Лейпцигского университета). Университет также управляет Музеем древностей . [84]

Основанный в марте 2015 года, G2 Kunsthalle размещает коллекцию Хильдебранда. [85] Эта частная коллекция посвящена так называемой Новой Лейпцигской школе . Первый частный музей Лейпцига, посвященный современному искусству в Лейпциге после рубежа тысячелетий, расположен в центре города недалеко от знаменитой церкви Святого Фомы на третьем этаже бывшего центра обработки ГДР. [86] Также современному искусству посвящена Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig . [87]

Другие музеи Лейпцига включают в себя следующие:

Лейпциг хорошо известен своими большими парками. Leipziger Auwald ( прибрежный лес ) находится в основном в черте города. Neuseenland — это район к югу от Лейпцига, где старые карьеры превращаются в огромный озерный край. Планируется, что работы будут завершены в 2060 году.

Иоганн Себастьян Бах провел самый долгий период своей карьеры в Лейпциге, с 1723 года до своей смерти в 1750 году, дирижируя Thomanerchor (хор церкви Св. Фомы) в церкви Св. Фомы , церкви Св. Николая и Paulinerkirche , университетской церкви Лейпцига (разрушена в 1968 году). Композитор Рихард Вагнер родился в Лейпциге в 1813 году, в Брюле . Роберт Шуман также принимал активное участие в музыкальной жизни Лейпцига, будучи приглашенным Феликсом Мендельсоном , когда последний основал в городе первую в Германии музыкальную консерваторию в 1843 году. Густав Малер был вторым дирижером (работавшим под руководством Артура Никиша ) в Лейпцигской опере с июня 1886 по май 1888 года и добился своего первого значительного признания, завершив и опубликовав оперу Карла Марии фон Вебера «Три пинта» . Малер также завершил свою Первую симфонию , живя в Лейпциге.

Сегодня консерватория — это Университет музыки и театра в Лейпциге . [89] Здесь преподается широкий спектр предметов, включая артистическую и педагогическую подготовку по всем оркестровым инструментам, вокалу, интерпретации, репетиторству, камерной фортепианной музыке , оркестровому дирижированию, хоровому дирижированию и музыкальной композиции в различных музыкальных стилях. На драматических факультетах преподают актерское мастерство и написание сценариев .

Bach -Archiv Leipzig , учреждение для документирования и исследования жизни и творчества Баха (а также семьи Бахов ), было основано в Лейпциге в 1950 году Вернером Нойманном . Bach-Archiv организует престижный Международный конкурс имени Иоганна Себастьяна Баха , инициированный в 1950 году как часть музыкального фестиваля, посвященного двухсотлетию со дня смерти Баха. В настоящее время конкурс проводится каждые два года в трех меняющихся категориях. Bach-Archiv также организует выступления, в частности международный фестиваль Bachfest Leipzig , и управляет Музеем Баха.

Музыкальные традиции города также нашли свое отражение во всемирной славе Лейпцигского оркестра Гевандхаус под управлением главного дирижера Андриса Нельсонса и хора Фомы.

Симфонический оркестр Лейпцигского радио MDR — второй по величине симфонический оркестр Лейпцига. Его нынешний главный дирижер — Кристьян Ярви . И Gewandhausorchester, и MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra выступают в концертном зале Gewandhaus .

На протяжении более шестидесяти лет Лейпциг предлагает программу «школьных концертов» [90] для детей в Германии: ежегодно проводится более 140 концертов на таких площадках, как Гевандхаус, которые посещают более 40 000 детей.

Лейпциг известен своей независимой музыкальной сценой и субкультурными мероприятиями. Лейпциг уже тридцать лет является домом для Wave-Gotik-Treffen (WGT), который в настоящее время является крупнейшим в мире готическим фестивалем, где в начале лета собираются тысячи поклонников готической музыки . Первый Wave Gotik Treffen состоялся в клубе Eiskeller, сегодня известном как Conne Island , в районе Конневиц . Знаменитый альбом Mayhem Live in Leipzig также был записан в клубе Eiskeller.

Leipzig Pop Up была ежегодной музыкальной ярмаркой для независимой музыкальной сцены, а также музыкальным фестивалем, проходившим в выходные Пятидесятницы . [91] Его самые известные инди-лейблы — Moon Harbour Recordings (хаус) и Kann Records (хаус/техно/психоделик). Несколько площадок часто предлагают живую музыку, включая Moritzbastei , [92] Tonelli's и Noch Besser Leben.

Die Prinzen («Принцы») — немецкая группа, основанная в Лейпциге. С почти шестью миллионами проданных записей они являются одной из самых успешных немецких групп.

Согласно аннотации к обложке альбома Gulag Orkestar группы из Бейрута 2005 года, она была украдена из библиотеки Лейпцига Заком Кондоном.

Город Лейпциг также является родиной Тилля Линдеманна , наиболее известного как вокалист группы Rammstein , образованной в 1994 году.

В городе более 300 спортивных клубов, представляющих 78 различных дисциплин. Более 400 спортивных сооружений доступны для граждан и членов клубов. [99]

The German Football Association (DFB) was founded in Leipzig in 1900. The city was the venue for the 2006 FIFA World Cup draw, and hosted four first-round matches and one match in the round of 16 in the central stadium.

VfB Leipzig won the first national Association football championship in 1903. The club was dissolved in 1946 and the remains reformed as SG Probstheida. The club was eventually reorganized as football club 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig in 1966. 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig has had a glorious past in international competition as well, having been champions of the 1965–66 Intertoto Cup, semi-finalists in the 1973–74 UEFA Cup, and runners-up in the 1986–87 European Cup Winners' Cup.

Red Bull took over a local 5th division football club SSV Markranstädt in May 2009, having previously been denied the right to buy into FC Sachsen Leipzig in 2006. The club was renamed RB Leipzig and came up through the ranks of German football, winning promotion to the Bundesliga, the highest division of German football in 2016.[100] The club finished runners-up in its first-ever Bundesliga season and made its debut in the UEFA Champions League in 2017 and the Semi-Final in 2020.

RB Leipzig won the DFB-Pokal football cup twice, in 2022 and 2023.

List of Leipzig men and women's football clubs playing at state level and above:

Note 1: The RB Leipzig women's football team was formed in 2016 and began play in the 2016–17 season.

Note 2: The club began play in the 2008–09 season.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, ice hockey has gained popularity, and several local clubs established departments dedicated to that sport.[101]

SC DHfK Leipzig is the men's handball club in Leipzig and were six times (1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1965 and 1966) the champion of East Germany handball league and was winner of EHF Champions League in 1966. They finally promoted to Handball-Bundesliga as champions of 2. Bundesliga in 2014–15 season. They play in the Arena Leipzig which has a capacity of 6,327 spectators in HBL games but can take up to 7,532 spectators for handball in maximum capacity.

Handball-Club Leipzig is one of the most successful women's handball clubs in Germany, winning 21 domestic championships since 1953 and 2 Champions League titles. The team was however relegated to the third tier league in 2017 due to failing to achieve the economic standard demanded by the league licence.

Leipzig Kings is an American football team playing in the European League of Football (ELF), which is a planned professional league, that is set to become the first fully professional league in Europe since the demise of NFL Europe.[102] The Kings will start playing games against teams from Germany, Spain and Poland in June 2021.[103] They play their home games at Alfred-Kunze-Sportpark.

The Motodrom am Cottaweg is a motorcycle speedway stadium on the west side of the Neue Luppe, located on the Cottaweg road.[104][105] The venue is used by the speedway club called Motorsport Club Post Leipzig e.V.[106] and held the East German Speedway Championship in 1978 and a qualifying round of the Speedway World Team Cup in 1991.[107]

From 1950 to 1990 Leipzig was host of the Deutsche Hochschule für Körperkultur (DHfK, German College of Physical Culture), the national sports college of the GDR.

Leipzig also hosted the Fencing World Cup in 2005 and hosts a number of international competitions in a variety of sports each year.

Leipzig made a bid to host the 2012 Summer Olympics. The bid did not make the shortlist after the International Olympic Committee pared the bids down to 5.

Markkleeberger See is a new lake next to Markkleeberg, a suburb on the south side of Leipzig. A former open-pit coal mine, it was flooded in 1999 with groundwater and developed in 2006 as a tourist area. On its southeastern shore is Germany's only pump-powered artificial whitewater slalom course, Markkleeberg Canoe Park (Kanupark Markkleeberg), a venue which rivals the Eiskanal in Augsburg for training and international canoe/kayak competition.

Leipzig Rugby Club competes in the German Rugby Bundesliga but finished at the bottom of their group in 2013.[108]

Leipzig hosted the Indoor Hockey World Cup in 2015. All matches were played in Leipzig Arena, with the Netherlands coming out victorious in both the men's and women's tournaments.

Leipzig University, founded 1409, is one of Europe's oldest universities. Karl Bücher, a German economist, founded the Institut für Zeitungswissenschaften (Institute for Newspaper Science) at the University of Leipzig in 1916. It was the first institute of its kind to be established in Europe, and it marks the commencement of academic study of media communication in Germany.[109]

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a philosopher and mathematician, was born in Leipzig in 1646, and attended the university from 1661 to 1666. Nobel Prize laureate Werner Heisenberg worked at the university as a physics professor (from 1927 to 1942), as did Nobel Prize laureates Gustav Ludwig Hertz (physics), Wilhelm Ostwald (chemistry) and Theodor Mommsen (Nobel Prize in literature). The 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine went to Svante Pääbo, an honorary professor at the university. Other former university staff include mineralogist Georg Agricola, writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, philosopher Ernst Bloch, founder of psychophysics Gustav Theodor Fechner, and founder of modern psychology, Wilhelm Wundt. The university's notable former students include writers Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Erich Kästner, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, political activist Karl Liebknecht, and composer Richard Wagner. Angela Merkel, former German chancellor, studied physics at Leipzig University.[110] The university has about 30,000 students.

A part of Leipzig University is the German Institute for Literature which was founded in 1955 under the name "Johannes R. Becher-Institut". Many noted writers have graduated from this school, including Heinz Czechowski, Kurt Drawert, Adolf Endler, Ralph Giordano, Kerstin Hensel, Sarah and Rainer Kirsch, Angela Krauß, Erich Loest, and Fred Wander. After its closure in 1990 the institute was refounded in 1995 with new teachers.

The Academy of Visual Arts (Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst) was established in 1764. Its 600 students (as of 2018[update]) are enrolled in courses in painting and graphics, book design/graphic design, photography and media art. The school also houses an Institute for Theory.

The University of Music and Theatre offers a broad range of subjects ranging from training in orchestral instruments, voice, interpretation, coaching, piano chamber music, orchestral conducting, choir conducting and musical composition to acting and scriptwriting.

The Leipzig University of Applied Sciences (HTWK)[111] has approximately 6,200 students (as of 2007[update]) and is (as of 2007[update]) the second biggest institution of higher education in Leipzig. It was founded in 1992, merging several older schools. As a university of applied sciences (German: Fachhochschule) its status is slightly below that of a university, with more emphasis on the practical parts of education. The HTWK offers many engineering courses, as well as courses in computer science, mathematics, business administration, librarianship, museum studies, and social work. It is mainly located in the south of the city.

The private Leipzig Graduate School of Management, (in German Handelshochschule Leipzig (HHL)), is the oldest business school in Germany. According to The Economist, HHL is one of the best schools in the world, ranked at number six overall.[112][113]

Branch campus of Lancaster University, it is the first public UK university with a campus in Germany. Lancaster University Leipzig was founded in 2020 and currently has a diverse international student body with more than 45 nationalities.

Leipzig is currently the home of twelve research institutes and the Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

Leipzig is home to one of the world's oldest schools, Thomasschule zu Leipzig (St. Thomas' School, Leipzig), which gained fame for its long association with the Bach family of musicians and composers.

The Lutheran Theological Seminary is a seminary of the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church in Leipzig.[114][115] The seminary trains students to become pastors for the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church or for member church bodies of the Confessional Evangelical Lutheran Conference.[116]

The city is a location for automobile manufacturing by BMW and Porsche in large plants north of the city. In 2011 and 2012 DHL transferred the bulk of its European air operations from Brussels Airport to Leipzig/Halle Airport. Kirow Ardelt AG, the world market leader in breakdown cranes, is based in Leipzig. The city also houses the European Energy Exchange, the leading energy exchange in Central Europe. VNG – Verbundnetz Gas AG, one of Germany's large natural gas suppliers, is headquartered at Leipzig. In addition, inside its larger metropolitan area, Leipzig has developed an important petrochemical centre.

Some of the largest employers in the area (outside of manufacturing) include software companies such as Spreadshirt and the various schools and universities in and around the Leipzig/Halle region. The University of Leipzig attracts millions of euros of investment yearly and celebrated its 600th birthday in 2009.

Leipzig also benefits from world-leading medical research (Leipzig Heart Centre) and a growing biotechnology industry.[117]

Many bars, restaurants and stores in the downtown area are patronized by German and foreign tourists. Leipzig Main Train Station is the location of a shopping mall.[118] Leipzig is one of Germany's most visited cities with over 3 million overnight stays in 2017.[119]

In 2010, Leipzig was included in the top 10 cities to visit by The New York Times,[81] and ranked 39th globally out of 289 cities for innovation in the 4th Innovation Cities Index published by Australian agency 2thinknow.[120] In 2015, Leipzig have among the 30 largest German cities the third best prospects for the future.[121] In recent years Leipzig has often been nicknamed the "Boomtown of eastern Germany" or "Hypezig".[25] As of 2013[update] it had the highest rate of population growth of any German city.[26]

Companies with operations in or around Leipzig include:

Leipzig has a dense network of socio-ecological infrastructures. Worth mentioning in the food sector are the Fairteiler of foodsharing[122] and the numerous Community-supported agricultures,[123] in the textile sector the Umsonstladen in Plagwitz,[124] in the bicycle self-help workshops the Radsfatz,[125] in the computer sector the Hackerspace Die Dezentrale,[126] and in the repair sector the Café kaputt.[127]

In December 2013, according to a study by GfK, Leipzig was ranked as the most livable city in Germany.[132][133]

In 2015/2016, Leipzig was named by the consumer portal verbraucherzentrale.de as the second-best city for students in Germany (after Munich).[134]

In a 2017 study from the Institut für Handelsforschung Köln, the Leipzig inner city ranked first among all large cities in Germany due to its urban aesthetics, gastronomy, and shopping opportunities.[135][136]

According to HWWI/Berenberg-Städteranking, since 2018 it also has the second-best future prospects of all cities in Germany, second to Munich in 2018 and Berlin in 2019.[137][138]

According to a 2017 Global Least & Most Stressful Cities Ranking by Zipjet, a London-based online laundry service, Leipzig was one of the least stressful cities in the World. It was ranked 25th out of 150 cities worldwide and above Dortmund, Cologne, Frankfurt, and Berlin.[139]

Leipzig was named European City of the Year at the 2019 Urbanism Awards.[140]

According to the 2019 study by Forschungsinstitut Prognos, Leipzig is the most dynamic region in Germany. Within 15 years, the city climbed 230 places and occupied in 2019 rank 104 of all 401 German regions.[141][142]

Leipzig was listed as one of 52 places to go in 2020 by The New York Times and the highest-ranking German destination.[143]

Leipzig Hauptbahnhof has been ranked the best railway station in Germany and the third-best in Europe in a consumer organisation poll, surpassed only by St Pancras railway station and Zürich Hauptbahnhof.[144]

Founded at the crossing of Via Regia and Via Imperii, Leipzig has been a major interchange of inter-European traffic and commerce since medieval times. After the Reunification of Germany, immense efforts to restore and expand the traffic network have been undertaken and left the city area with an excellent infrastructure.

Opened in 1915, Leipzig Hauptbahnhof (lit. main station) is the largest overhead railway station in Europe in terms of its built-up area. At the same time, it is an important supra-regional junction in the Intercity-Express (ICE) and Intercity network of the Deutsche Bahn as well as a connection point for S-Bahn and regional traffic in the Halle/Leipzig area.

In Leipzig the Intercity Express routes (Hamburg–)Berlin–Leipzig–Nuremberg–Munich and Dresden–Leipzig–Erfurt–Frankfurt am Main–(Wiesbaden/Saarbrücken) intersect. Leipzig is also the starting point for the intercity lines Leipzig-Halle (Saale)–Magdeburg–Hannover–Dortmund–Köln and –Bremen–Oldenburg(–Norddeich Mole). Both lines complement each other at hourly intervals and also stop at Leipzig/Halle Airport. The only international connection is the daily EuroCity Leipzig-Prague.

Most major and medium-sized towns in Saxony and southern Saxony-Anhalt can be reached without changing trains. There are also direct connections via regional express lines to Falkenberg/Elster-Cottbus, Hoyerswerda and Dessau-Magdeburg as well as Chemnitz. Neighbouring Halle (Saale) can be reached via three S-Bahn lines, two of which run via Leipzig/Halle Airport. The surrounding area of Leipzig is served by numerous regional and S-Bahn lines.

The city's railway connections are currently being greatly improved by major construction projects, particularly within the framework of the German Unity transport projects. The line to Berlin has been extended and has been passable at 200 km/h (120 mph) since 2006. On 13 December 2015, the high-speed line from Leipzig to Erfurt, designed for 300 km/h (190 mph), was put into operation. Its continuation to Nuremberg followed in December 2017. This integration into the high-speed network considerably reduced the journey times of the ICE from Leipzig to Nuremberg, Munich and Frankfurt am Main. The Leipzig-Dresden railway line, which was the first German long-distance railway to go into operation in 1839, is also undergoing expansion for 200 km/h. The most important construction project in regional transport was the four-kilometer-long city tunnel, which went into operation in December 2013 as the main line of the S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland.

There are freight stations in the districts of Wahren and Engelsdorf. In addition, a freight traffic centre has been set up near the Schkeuditzer Kreuz junction for goods handling between road and rail, as well as a freight station on the site of the DHL hub at Leipzig/Halle Airport.

Leipzig is the core of the S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland line network. Together with the tram, six of the ten lines form the backbone of local public transport and an important link to the region and the neighbouring Halle. The main line of the S-Bahn consists of the underground S-Bahn stations Hauptbahnhof, Markt, Wilhelm-Leuschner-Platz and Bayerischer Bahnhof leading through the City Tunnel as well as the above-ground station Leipzig MDR. There are a total of 30 S-Bahn stations in the Leipzig city area. Endpoints of the S-Bahn lines include Wurzen, Zwickau, Dessau, and Lutherstadt Wittenberg. Two lines run to Halle, one of them via Leipzig/Halle Airport.

With the timetable change in December 2004, the networks of Leipzig and Halle were combined to form the Leipzig-Halle S-Bahn. However, this network only served as a transitional solution and was replaced by the S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland on 15 December 2013. At the same time, the main line tunnel, marketed as the Leipzig City Tunnel, went into operation. The tunnel, which is almost four kilometres long, crosses the entire city centre from the main railway station to the Bavarian railway station. The S-Bahn stations are up to 22 metres underground. This construction was the first to create a continuous north–south axis, which had not existed until now due to the north-facing terminus station. The connection to the south of the city and the federal state will thus be greatly improved.

The Leipziger Verkehrsbetriebe, existing since 1 January 1917, operate a total of 15 tram lines and 47 bus lines in the city.

The total length of the tram network is 146 km (91 mi), making it the largest in Saxony ahead of Dresden (134.4 km (83.5 mi)) and the second largest in Germany after Berlin (196 km (122 mi)).

The longest line in the Leipzig network is line 11, which connects Schkeuditz with Markkleeberg over 22 kilometres and is the only tram line in Leipzig to run in three tariff zones of the Central German Transport Association.

Night bus lines N1 to N9 and the night tram N17 operate in the night traffic. On Saturdays, Sundays and holidays the tram line N10 and the bus line N60 also operate. The central transfer point between the bus and tram lines as well as to the S-Bahn is Leipzig Central Station.

Like most German cities, Leipzig has a traffic layout designed to be bicycle-friendly. There is an extensive cycle network. In most of the one-way central streets, cyclists are explicitly allowed to cycle both ways. A few cycle paths have been built or declared since 1990. According to the data from the 2021/22 traffic count, the Saxons' Bridge has the highest traffic occupancy with over 15,000 cyclists per day in cycling in Leipzig.[145]

Since 2004 there is a bicycle-sharing system. Bikes can be borrowed and returned via smartphone app or by telephone. Since 2018, the system has enabled flexible borrowing and returning of bicycles in the inner city; in this zone, bicycles can be handed in and borrowed from almost any street corner. Outside these zones, there are stations where the bikes are waiting. The current locations of the bikes can be seen via the app. There are cooperation offers with the Leipzig public transport companies and car sharing in order to offer as complete a mobility chain as possible.

Several federal motorways pass by Leipzig: the A 14 in the north, the A 9 in the west, and the A 38 in the south. The three motorways form a triangular partial ring of the double ring Mitteldeutsche Schleife around Halle and Leipzig. To the south towards Chemnitz, the A 72 is also partly under construction.

The federal roads B 2, B 6, B 87, B 181, and B 184 lead through the city area.

The ring road (Innenstadtring), which corresponds to the course of the old city fortification, surrounds the city centre of Leipzig, which today is largely traffic-calmed.

Leipzig has a dense network of carsharing stations. Additionally, since 2018 there is also a stationless car sharing system in Leipzig. Here the cars can be parked and booked anywhere in the inner city without having to define a specific car or period in advance. Finding and booking is done via a smartphone app.

Leipzig is one of the few cities in Germany with vehicle for hire services that can be booked via a mobile app. In contrast to taxicab services, the start and destination must be defined beforehand and other passengers can be taken along at the same time if they share a route.

Since March 2018 there has been a central bus station directly east of Leipzig Central Station.

In addition to a large number of national lines, several international lines also serve Leipzig. The cities of Bregenz, Budapest, Milan, Prague, Sofia and Zurich, among others, can be reached without having to change trains. Around 30,000 journeys and 1.5 million passengers a year are expected at the new bus station.

Some lines also use Leipzig/Halle Airport, located at the A 9/A 14 motorway junction, and Leipziger Messe for a stop. Passengers can take the S-Bahn from there to the city centre.

Leipzig/Halle Airport is the international commercial airport of the region. It is located at the Schkeuditzer Kreuz junction northwest of Leipzig, halfway between the two major cities. The easternmost section of the new Erfurt-Leipzig/Halle line under construction gave the airport a long-distance railway station, which was also integrated into the ICE network when the railway line was completed in 2015.

Passenger flights are operated to and from the major German hub airports, European metropolises and holiday destinations, especially to the Mediterranean region and North Africa. The airport is of international importance in the cargo sector. In Germany, it ranks second behind Frankfurt am Main, fifth in Europe and 26th worldwide (as of 2011). DHL uses the airport as its central European hub. It is also the home base of the freight airlines Aerologic and European Air Transport Leipzig.

The former military airport near Altenburg, Thuringia, called Leipzig-Altenburg Airport, about a half-hour drive from Leipzig, was served by Ryanair until 2010.

In the first half of the 20th century, the construction of the Elster-Saale canal, White Elster, and Saale was started in Leipzig in order to connect to the network of waterways. The outbreak of the Second World War stopped most of the work, though some may have continued through the use of forced labor. The Lindenauer port was almost completed but not yet connected to the Elster-Saale and Karl Heine Canal respectively. The Leipzig rivers (White Elster, New Luppe, Pleiße, and Parthe) in the city have largely artificial river beds and are supplemented by some channels. These waterways are suitable only for small leisure boat traffic.

Through the renovation and reconstruction of existing mill races and watercourses in the south of the city and flooded disused open cast mines, the city's navigable water network is being expanded. A link between Karl Heine Canal and the disused Lindenauer port was opened in 2015. Still more work was scheduled to complete the Elster-Saale canal. Such a move would allow small boats to reach the Elbe from Leipzig. The intended completion date has been postponed because of an unacceptable cost-benefit ratio.

Mein Leipzig lob' ich mir! Es ist ein klein Paris und bildet seine Leute. ("I praise my Leipzig! It is a small Paris and educates its people.") – Frosch, a university student in Goethe's Faust, Part One

Ich komme nach Leipzig, an den Ort, wo man die ganze Welt im Kleinen sehen kann. ("I'm coming to Leipzig, to the place where one can see the whole world in miniature.") – Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

Extra Lipsiam vivere est miserrime vivere. ("To live outside Leipzig is to live miserably.") – Benedikt Carpzov the Younger

Das angenehme Pleis-Athen, Behält den Ruhm vor allen, Auch allen zu gefallen, Denn es ist wunderschön. ("The pleasurable Pleiss-Athens, earns its fame above all, appealing to every one, too, for it is mightily beauteous.") – Johann Sigismund Scholze

Leipzig is twinned with:[146]

.jpg/440px-Christoph_Bernhard_Francke_-_Bildnis_des_Philosophen_Leibniz_(ca._1695).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Riccardo_Chailly_(1986).jpg)

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link){{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)...Clara Schumann (1819–1896).....had a brilliant career as a pianist...