Халифат или хилафа ( араб . خِلَافَةْ [xi'laːfah] ) — монархическая форма правления (первоначально выборная , позднее абсолютная ), возникшая в Аравии VII века , политическая идентичность которой основана на притязаниях на преемственность Исламского государства Мухаммеда и идентификации монарха, называемого халифом [1] [2] [3] ( / ˈ k æ l ɪ f , ˈ k eɪ -/ ; араб . خَلِيفَةْ [xæ'liːfæh] , ), как его наследника и преемника. Титул халифа, который был эквивалентом таких титулов, как король , царь и хан в других частях мира, привел ко многим гражданским войнам , сектантским конфликтам и параллельным региональным халифатам. Исторически халифаты были политиями, основанными на исламе, которые развились в многоэтнические транснациональные империи. [4] [5]

В средневековый период сменяли друг друга три крупных халифата: Рашидунский халифат (632–661), Омейядский халифат (661–750) и Аббасидский халифат (750–1517). В четвертом крупном халифате, Османском халифате , правители Османской империи претендовали на халифскую власть с 1517 года до тех пор, пока Османский халифат не был официально упразднен в рамках секуляризации Турции в 1924 году . Была предпринята попытка сохранить титул с Шарифским халифатом , но этот халифат быстро пал после его завоевания султанатом Неджд (нынешняя Саудовская Аравия ), оставив претензии в состоянии покоя. На протяжении всей истории ислама несколько других мусульманских государств, почти все из которых были наследственными монархиями, такими как Мамлюкский султанат и Айюбидский султанат , претендовали на звание халифатов.

Не во всех мусульманских государствах были халифаты. Суннитская ветвь ислама предусматривает, что в качестве главы государства халиф должен избираться мусульманами или их представителями. [6] Шииты , однако, верят, что халифом должен быть имам, избранный Богом из Ахль аль-Байт («Семейство Пророка»). Некоторые халифаты в истории возглавлялись шиитами, как, например, халифат Фатимидов (909–1171). С конца 20-го века до начала 21-го века, в результате вторжения СССР в Афганистан , войны с террором и Арабской весны , различные исламистские группы претендовали на халифат, хотя эти претензии обычно широко отвергались среди мусульман.

До появления ислама аравийские монархи традиционно использовали титул малик (король) или другой титул от того же корня . [7] Термин халиф ( / ˈ k eɪ l ɪ f , ˈ k æ l ɪ f / ), [8] происходит от арабского слова khalīfah ( خَليفة , ), что означает «преемник», «управляющий» или «заместитель» и традиционно считалось сокращением от Khalīfah Rasūl Allah («преемник посланника Бога»). Однако исследования доисламских текстов показывают, что первоначальное значение фразы было «преемник, избранный Богом». [7]

Сразу после смерти Мухаммеда в Сакифе (дворе) клана Бану Саида состоялась встреча ансаров (уроженцев Медины ) . [9] В то время считалось, что целью встречи было решение ансаров о новом лидере мусульманской общины среди себя, с намеренным исключением мухаджиров ( мигрантов из Мекки ), хотя позже это стало предметом споров. [10]

Тем не менее, Абу Бакр и Умар , оба видных соратника Мухаммеда, узнав о встрече, забеспокоились о возможном перевороте и поспешили на собрание. Прибыв, Абу Бакр обратился к собравшимся мужчинам с предупреждением, что попытка избрать лидера за пределами собственного племени Мухаммеда, курайшитов , скорее всего, приведет к разногласиям, поскольку только они могут заслужить необходимое уважение в общине. Затем он взял Умара и другого соратника, Абу Убайду ибн аль-Джарраха , за руки и предложил их ансарам в качестве потенциальных выборов. Ему ответили предложением, чтобы курайшиты и ансары выбрали лидера каждый из себя, который затем будет править совместно. Группа разгорячилась, услышав это предложение, и начала спорить между собой. Умар поспешно взял руку Абу Бакра и поклялся в верности последнему, примеру, которому последовали собравшиеся мужчины. [11]

Абу Бакр был почти повсеместно принят в качестве главы мусульманской общины (под титулом халифа) в результате Сакифы, хотя он столкнулся с разногласиями из-за поспешного характера события. Несколько сподвижников, наиболее выдающимся из которых был Али ибн Аби Талиб , изначально отказались признать его власть. [12] Али, возможно, разумно ожидалось, что он возьмет на себя руководство, будучи и двоюродным братом, и зятем Мухаммеда. [13] Теолог Ибрагим ан-Нахаи утверждал, что Али также имел поддержку среди ансаров в отношении его преемственности, что объясняется его генеалогическими связями, которые он разделял с ними. Неизвестно, была ли его кандидатура на преемственность поднята во время Сакифы, хотя это не маловероятно. [14] Позже Абу Бакр послал Умара противостоять Али, чтобы заручиться его преданностью, что привело к ссоре , которая могла включать насилие. [15] Однако через шесть месяцев группа заключила мир с Абу Бакром, и Али предложил ему свою верность. [16]

Абу Бакр назначил Умара своим преемником на смертном одре. Умар, второй халиф, был убит персидским рабом по имени Абу Лулуа Фируз . Его преемник, Усман, был избран советом выборщиков ( маджлисом ). Усман был убит членами недовольной группы. Затем Али взял под контроль, но не был повсеместно принят в качестве халифа правителями Египта, а позже и некоторыми из его собственной гвардии. Он столкнулся с двумя крупными восстаниями и был убит Абд-аль-Рахманом ибн Мулджамом , хариджитом . Бурное правление Али длилось всего пять лет. Этот период известен как Фитна , или первая исламская гражданская война. Последователи Али позже стали шиитами («шиит Али», сторонники Али. [17] ) — меньшинством секты ислама и отвергают легитимность первых трех халифов. Последователи всех четырех праведных халифов (Абу Бакра, Умара, Усмана и Али) стали преобладающей суннитской сектой.

При Рашидуне каждая область ( султанат , вилайет или эмират ) халифата имела своего собственного губернатора (султана, вали или эмира ). Муавия , родственник Усмана и губернатор ( вали ) Сирии , стал преемником Али в качестве халифа. Муавия превратил халифат в наследственную должность, тем самым основав династию Омейядов .

В районах, которые ранее находились под властью Сасанидской империи или Византии , халифы снизили налоги, предоставили большую местную автономию (своим делегированным губернаторам), большую религиозную свободу для евреев и некоторых местных христиан и принесли мир народам, деморализованным и недовольным потерями и тяжелыми налогами, которые стали результатом десятилетий византийско-персидской войны . [18]

Правление Али было омрачено беспорядками и внутренними распрями. Персы, воспользовавшись этим, проникли в две армии и атаковали другую армию, вызвав хаос и внутреннюю ненависть между соратниками в битве при Сиффине . Битва длилась несколько месяцев, зайдя в тупик. Чтобы избежать дальнейшего кровопролития, Али согласился на переговоры с Муавией. Это заставило фракцию из примерно 4000 человек, которые стали известны как хариджиты , отказаться от борьбы. После победы над хариджитами в битве при Нахраване Али был позже убит хариджитом Ибн Мулджамом. Сын Али Хасан был избран следующим халифом, но отрекся от престола в пользу Муавии несколько месяцев спустя, чтобы избежать любого конфликта внутри мусульман. Муавия стал шестым халифом, основав династию Омейядов, [19] названную в честь прадеда Усмана и Муавии, Умайи ибн Абд Шамса . [20]

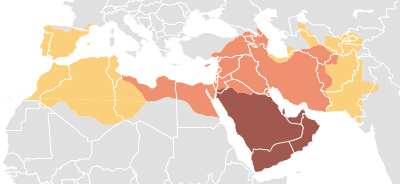

Начиная с Омейядов, титул халифа стал наследственным. [21] При Омейядах территория халифата быстро росла, включив в мусульманский мир Кавказ , Трансоксанию , Синд , Магриб и большую часть Пиренейского полуострова ( Аль-Андалус ). [22] В наибольшей степени Омейядский халифат охватывал 5,17 миллионов квадратных миль (13 400 000 км 2 ), что делало его крупнейшей империей, которую когда-либо видел мир, и седьмой по величине, когда-либо существовавшей в истории. [23]

Географически империя была разделена на несколько провинций, границы которых менялись много раз во время правления Омейядов. [ требуется ссылка ] В каждой провинции был губернатор, назначаемый халифом. Однако по ряду причин, включая то, что они не были избраны Шурой , и предположения о нечестивом поведении, династия Омейядов не пользовалась всеобщей поддержкой в мусульманской общине. [24] Некоторые поддерживали видных ранних мусульман, таких как Зубайр ибн аль-Аввам ; другие считали, что править должны только члены клана Мухаммеда, Бану Хашим , или его собственная родословная, потомки Али. [25]

Против Омейядов вспыхнули многочисленные восстания, а также произошел раскол в рядах Омейядов (в частности, соперничество между Йеманом и Кайсом ). [26] Под командованием Язида, сына Муавии, армия во главе с Умаром ибн Саадом, командиром по имени Шимр ибн Тиль-Джавшан, убила сына Али Хусейна и его семью в битве при Кербеле в 680 году, укрепив раскол между шиитами и суннитами . [17] В конце концов, сторонники Бану Хашим и сторонники рода Али объединились, чтобы свергнуть Омейядов в 750 году. Однако Шиат Али , «Партия Али», снова была разочарована, когда династия Аббасидов пришла к власти, поскольку Аббасиды были потомками дяди Мухаммеда, Аббаса ибн Абд аль-Мутталиба , а не Али. [27]

В 750 году династия Омейядов была свергнута другой семьей мекканского происхождения, Аббасидами. Их время представляло собой научный, культурный и религиозный расцвет. [28] Исламское искусство и музыка также значительно расцвели во время их правления. [29] Их главный город и столица Багдад начал процветать как центр знаний, культуры и торговли. Этот период культурного расцвета закончился в 1258 году разграблением Багдада монголами под предводительством Хулагу-хана . Однако Аббасидский халифат утратил свою эффективную власть за пределами Ирака уже около 920 года. [30] К 945 году потеря власти стала официальной, когда Буиды завоевали Багдад и весь Ирак. Империя распалась, и ее части в течение следующего столетия управлялись местными династиями. [31]

В девятом веке Аббасиды создали армию, лояльную только своему халифату, состоящую преимущественно из тюркских половцев, черкесов и грузинских рабов, известных как мамлюки. [32] [33] К 1250 году мамлюки пришли к власти в Египте. Армия мамлюков, хотя ее часто рассматривали негативно, как помогала, так и вредила халифату. Поначалу она обеспечивала правительство стабильной силой для решения внутренних и внешних проблем. Однако создание этой иностранной армии и перенос столицы аль-Мутасимом из Багдада в Самарру создали разделение между халифатом и народами, которыми они, как утверждали, правили. Кроме того, власть мамлюков неуклонно росла, пока Ар-Ради (934–941) не был вынужден передать большую часть королевских функций Мухаммаду ибн Раику .

В 1261 году, после монгольского завоевания Багдада , мамлюкские правители Египта попытались обрести легитимность своего правления, объявив о восстановлении халифата Аббасидов в Каире . [ требуется цитата ] У халифов Аббасидов в Египте не было политической власти; они продолжали поддерживать символы власти, но их влияние ограничивалось религиозными вопросами. [ требуется цитата ] Первым халифом Аббасидов Каира был Аль-Мустансир (правил в июне-ноябре 1261 года). Халифат Аббасидов Каира просуществовал до времен Аль-Мутаваккиля III , который правил как халиф с 1508 по 1516 год, затем он был ненадолго свергнут в 1516 году своим предшественником Аль-Мустамсиком , но был снова восстановлен в халифате в 1517 году. [ требуется цитата ]

Османский султан Селим I разгромил султанат мамлюков и сделал Египет частью Османской империи в 1517 году. Аль-Мутаваккиль III был схвачен вместе со своей семьей и доставлен в Константинополь в качестве пленника, где у него была церемониальная роль. Он умер в 1543 году, после возвращения в Каир. [34]

К первой половине X века династия Аббасидов утратила фактическую власть над большей частью мусульманского государства.

Династия Омейядов, которая выжила и стала править Аль-Андалусом , вернула себе титул халифа в 929 году и правила им до своего свержения в 1031 году.

Во времена династии Омейядов Пиренейский полуостров был неотъемлемой провинцией Омейядского халифата, правившего из Дамаска . Омейяды потеряли должность халифа в Дамаске в 750 году, и Абд ар-Рахман I стал эмиром Кордовы в 756 году после шести лет изгнания. Намереваясь вернуть себе власть, он победил существующих исламских правителей региона, которые бросили вызов правлению Омейядов, и объединил различные местные феоды в эмират.

Правители эмирата использовали титул «эмир» или «султан» до десятого века, когда Абд ар-Рахман III столкнулся с угрозой вторжения со стороны халифата Фатимидов. Чтобы помочь своей борьбе против вторгшихся Фатимидов, которые претендовали на халифат в противовес общепризнанному халифу Багдада Аббасидам Аль-Мутадиду , Абд ар-Рахман III сам присвоил себе титул халифа. Это помогло Абд ар-Рахману III завоевать авторитет среди своих подданных, и титул был сохранен после того, как Фатимиды были отброшены. Правление халифата считается расцветом мусульманского присутствия на Пиренейском полуострове, до того, как он распался на различные тайфы в одиннадцатом веке. Этот период характеризовался расцветом технологий, торговли и культуры; многие здания Аль-Андалуса были построены в этот период.

Халифат Альмохадов ( берберские языки : Imweḥḥden , от арабского الموحدون al-Muwaḥḥidun , « Единобожие » или «Объединители») был марокканским [35] [36] берберским мусульманским движением, основанным в XII веке. [37]

Движение Альмохадов было начато Ибн Тумартом среди племен Масмуда на юге Марокко. Альмохады впервые основали берберское государство в Тинмеле в Атласских горах примерно в 1120 году. [37] Альмохадам удалось свергнуть династию Альморавидов , управлявших Марокко, к 1147 году, когда Абд аль-Мумин (годы правления 1130–1163) завоевал Марракеш и объявил себя халифом. Затем к 1159 году они распространили свою власть на весь Магриб . Аль-Андалус последовал за Африкой, и вся исламская Иберия оказалась под властью Альмохадов к 1172 году. [38]

Господство Альмохадов в Иберии продолжалось до 1212 года, когда Мухаммед ан-Насир (1199–1214) потерпел поражение в битве при Лас-Навас-де-Толоса в Сьерра-Морене от союза христианских принцев Кастилии , Арагона , Наварры и Португалии . [ необходима ссылка ] Вскоре после этого почти все мавританские владения в Иберии были потеряны, а крупные мавританские города Кордова и Севилья пали под натиском христиан в 1236 и 1248 годах соответственно.

Альмохады продолжали править в Северной Африке до тех пор, пока частичная потеря территории из-за восстаний племен и округов не привела к возвышению их самых могущественных врагов — династии Маринидов в 1215 году. [ необходима ссылка ] Последний представитель этой линии, Идрис аль-Ватик , был низведен до владения Марракешем , где он был убит рабом в 1269 году; Мариниды захватили Марракеш, положив конец господству Альмохадов в Западном Магрибе .

Халифат Фатимидов был исмаилитским шиитским халифатом, изначально базировавшимся в Тунисе , который распространил свою власть на средиземноморское побережье Африки и в конечном итоге сделал Египет центром своего халифата. На пике своего развития, помимо Египта, халифат включал различные области Магриба , Сицилии, Леванта и Хиджаза .

Фатимиды основали тунисский город Махдию и сделали его своей столицей, прежде чем завоевать Египет и построить там город Каир в 969 году. После этого Каир стал столицей халифата, а Египет стал политическим, культурным и религиозным центром государства. Исламский ученый Луи Массиньон назвал четвертый век хиджры / десятый век н. э. « веком исмаилитов в истории ислама». [39]

Термин «Фатимиды» иногда используется для обозначения граждан этого халифата. Правящая элита государства принадлежала к исмаилитской ветви шиизма. Лидеры династии были исмаилитскими имамами и имели религиозное значение для мусульман-исмаилитов. Они также являются частью цепочки держателей должности халифата, как признают некоторые мусульмане. Таким образом, это редкий период в истории, в который потомки Али (отсюда и название «Фатимиды», относящееся к жене Али Фатиме ) и халифат были объединены в какой-либо степени, за исключением последнего периода халифата Рашидун под руководством самого Али .

Халифат, как известно, проявлял определенную степень религиозной терпимости по отношению к неисмаилитским сектам ислама, а также к евреям, мальтийским христианам и коптам . [40]

Шиит Убайд Аллах аль-Махди Биллах из династии Фатимидов , который утверждал, что является потомком Мухаммеда через свою дочь, в 909 году присвоил себе титул халифа, создав отдельную линию халифов в Северной Африке. Первоначально контролируя Алжир , Тунис и Ливию , халифы Фатимидов продлили свое правление на следующие 150 лет, захватив Египет и Палестину , прежде чем династия Аббасидов смогла переломить ситуацию, ограничив правление Фатимидов Египтом. Династия Фатимидов окончательно закончилась в 1171 году и была настигнута Саладином из династии Айюбидов . [41]

На халифат претендовали султаны Османской империи, начиная с Мурада I (правил с 1362 по 1389 гг.), [42] не признавая никакой власти со стороны халифов Аббасидов в управляемом мамлюками Каире. Поэтому резиденция халифата переместилась в османскую столицу Эдирне . В 1453 году, после завоевания Константинополя Мехмедом Завоевателем , резиденция османов переместилась в Константинополь , современный Стамбул . В 1517 году османский султан Селим I разгромил и присоединил к своей империи мамлюкский султан Каира. [43] [44] Завоевав и объединив мусульманские земли, Селим I стал защитником священных городов Мекки и Медины , что еще больше укрепило османские притязания на халифат в мусульманском мире. Османы постепенно стали рассматриваться как фактические лидеры и представители исламского мира. Однако ранние османские халифы официально не носили титул халифа в своих государственных документах, надписях или монетах. [44] Только в конце восемнадцатого века султаны обнаружили, что притязания на халифат имеют практическое применение, поскольку они позволяли им противостоять российским притязаниям на защиту османских христиан собственными притязаниями на защиту мусульман под властью России. [45] [46]

Итог русско-турецкой войны 1768–1774 годов был катастрофическим для османов. Большие территории, в том числе с большим мусульманским населением, такие как Крым , были потеряны для Российской империи. [46] Однако османы под руководством Абдул-Хамида I заявили о дипломатической победе, получив разрешение остаться религиозными лидерами мусульман в теперь независимом Крыму в рамках мирного договора; взамен Россия стала официальным защитником христиан на территории Османской империи. [46] По словам Бартольда, впервые титул «халиф» был использован османами как политический, а не символический религиозный титул в Кючук-Кайнарджийском договоре с Российской империей в 1774 году, когда империя сохранила моральный авторитет на территории , суверенитет которой был передан Российской империи. [46] Британцы тактично подтвердили бы притязания Османской империи на халифат и продолжили бы заставлять Османского халифа отдавать приказы мусульманам, проживающим в Британской Индии, подчиняться британскому правительству. [47]

Британцы поддерживали и пропагандировали мнение о том, что османы были халифами ислама среди мусульман Британской Индии, а османские султаны помогали британцам, выпуская заявления для мусульман Индии, призывая их поддерживать британское правление султана Селима III и султана Абдул-Меджида I. [47]

Около 1880 года султан Абдул Хамид II восстановил титул как способ противодействия российской экспансии на мусульманские земли. Его притязания были наиболее горячо приняты мусульманами-суннитами Британской Индии . [48] К началу Первой мировой войны Османское государство, несмотря на свою слабость по сравнению с Европой, представляло собой крупнейшее и наиболее могущественное независимое исламское политическое образование. Султан также пользовался некоторой властью за пределами своей уменьшающейся империи как халиф мусульман в Египте, Индии и Центральной Азии. [ необходима цитата ]

В 1899 году Джон Хэй , государственный секретарь США, попросил американского посла в Османской Турции Оскара Штрауса обратиться к султану Абдулу Хамиду II, чтобы тот, используя свое положение халифа, приказал народу таусуг султаната Сулу на Филиппинах подчиниться американскому сюзеренитету и американскому военному правлению; султан обязал их и написал письмо, которое было отправлено в Сулу через Мекку. В результате «магометане Сулу... отказались присоединиться к мятежникам и отдали себя под контроль нашей армии, тем самым признав американский суверенитет». [49] [50]

После Мудросского перемирия в октябре 1918 года с военной оккупацией Константинополя и Версальского договора (1919) положение османов было неопределенным. Движение за защиту или восстановление османов набрало силу после Севрского договора (август 1920 года), который навязал раздел Османской империи и дал Греции сильное положение в Анатолии, к несчастью для турок. Они призвали на помощь, и движение стало результатом. Движение рухнуло к концу 1922 года.

3 марта 1924 года первый президент Турецкой Республики Мустафа Кемаль Ататюрк в рамках своих реформ конституционно отменил институт халифата. [43] Ататюрк предложил халифат Ахмеду Шарифу ас-Сенусси при условии, что он будет проживать за пределами Турции; Сенусси отклонил предложение и подтвердил свою поддержку Абдул-Меджиду . [51] Затем на этот титул претендовал Хусейн бин Али, Шериф Мекки и Хиджаза , лидер Арабского восстания , но его королевство было побеждено и аннексировано ибн Саудом в 1925 году.

Египетский ученый Али Абдель Разик опубликовал свою книгу 1925 года «Ислам и основы управления ». Аргумент этой книги был обобщен как «Ислам не пропагандирует определенную форму правления». [52] Он сосредоточил свою критику как на тех, кто использует религиозный закон как современный политический запрет, так и на истории правителей, претендующих на легитимность халифата. [53] Разик писал, что прошлые правители распространяли идею религиозного оправдания халифата, «чтобы они могли использовать религию как щит, защищающий их троны от нападений мятежников». [54]

В 1926 году в Каире был созван саммит для обсуждения возрождения халифата, но большинство мусульманских стран не участвовали, и не было предпринято никаких действий для реализации резолюций саммита. Хотя титул Амир аль-Муминин был принят королем Марокко и Мухаммедом Омаром , бывшим главой Талибана Афганистана , ни один из них не претендовал на какой-либо правовой статус или власть над мусульманами за пределами границ своих стран. [ необходима цитата ]

После распада Османской империи время от времени проводились демонстрации, призывающие к восстановлению халифата. К организациям, призывающим к восстановлению халифата, относятся Хизб ут-Тахрир и Братья-мусульмане . [55] Правительство ПСР в Турции, бывшего союзника Братьев-мусульман, которое приняло неоосманистскую политику на протяжении всего своего правления, обвинялось в намерении восстановить халифат. [56] [57]

После походов Омейядов в Индию и завоевания небольших территорий в западной части полуострова Индостан, ранние индийские мусульманские династии были основаны династией Гуридов и Газневидов , в первую очередь Делийский султанат . Индийские султанаты не стремились широко к халифату, поскольку Османская империя уже соблюдала халифат. [58]

Императоры империи Великих Моголов , которые были единственными суннитскими правителями, чьи территории и богатства могли конкурировать с территориями и богатствами Османов, начали принимать титул халифа и называть свою столицу Дар-уль-хилафат («обитель халифата») со времен третьего императора Акбара, как и их предки Тимуриды. Золотая монета, отчеканенная при Акбаре, называла его «великим султаном , возвышенным халифом ». Хотя Моголы не признавали верховенства Османов, они тем не менее использовали титул халифа, чтобы почтить их в дипломатических обменах. Письмо Акбара к Сулейману Великолепному обращалось к последнему как к достигшему ранга халифата, в то время как империя Акбара называлась «Халифатом царств Хинда и Синда». [59] Пятый император Шах Джахан также претендовал на халифат. [60] Хотя Империя Великих Моголов не признана халифатом, ее шестой император Аурангзеб часто рассматривается как один из немногих исламских халифов, правивших Индийским полуостровом. [61] Он получил поддержку от османских султанов, таких как Сулейман II и Мехмед IV . Как знаток Корана, Аурангзеб полностью установил шариат в Южной Азии с помощью своей фетвы «Аламгири» . [62] Он вновь ввел джизью и запретил противозаконные с точки зрения ислама виды деятельности. Однако личные расходы Аурангзеба покрывались его собственными доходами, которые включали шитье шапок и торговлю его письменными копиями Корана. Таким образом, его сравнивали со вторым халифом, Умаром ибн Хаттабом , и курдским завоевателем Саладином . [63] [64] Императоры Великих Моголов продолжали называться халифами вплоть до правления Шаха Алама II . [65]

Другие известные правители, такие как Мухаммад бин Бахтияр Халджи , Алауддин Хилджи , Фируз Шах Туглак , Шамсуддин Ильяс Шах , Бабур , Шер Шах Сури , Насир I из Калата , Типу Султан , навабы Бенгалии и Ходжа Салимулла , широко получали термин халифа . [66]

Халифат Борну, который возглавляли императоры Борну, возник в 1472 году. Это было государство-осколок более крупной империи Канем-Борну , его правители носили титул халифа до 1893 года, когда оно было поглощено британской колонией Нигерия и протекторатом Северный Камерун . Британцы признали их «султанами Борну», на одну ступень ниже в мусульманских королевских титулах. После того, как Нигерия стала независимой, ее правители стали «эмирами Борну», еще на одну ступень ниже.

Индонезийский султан Джокьякарты исторически использовал Халифатулла (Халиф Божий) как один из своих многочисленных титулов. В 2015 году султан Хаменгкубувоно X отказался от любых претензий на халифат, чтобы облегчить наследование престола своей дочерью , поскольку теологическое мнение того времени состояло в том, что женщина может занимать светскую должность султана, но не духовную должность халифа. [67]

Сокотский халифат был исламским государством на территории современной Нигерии во главе с Усманом даном Фодио . Основанный во время войны с фулани в начале девятнадцатого века, он контролировал одну из самых могущественных империй в Африке к югу от Сахары до европейского завоевания и колонизации, достигшей кульминации в войнах Адамава и битве при Кано . Халифат сохранялся в течение колониального периода и после него, хотя и с уменьшенной властью. [ требуется цитата ] Нынешний глава Сокотского халифата — Сааду Абубакар .

Империя Тукулёр , также известная как Империя Тукулар, была одним из государств джихада Фулани в Африке к югу от Сахары. В конечном итоге она была усмирена и аннексирована Французской Республикой , будучи включенной в состав Французской Западной Африки .

Движение Халифат было основано мусульманами в Британской Индии в 1920 году для защиты Османского халифата в конце Первой мировой войны и распространилось по всем британским колониальным территориям. Оно было сильным в Британской Индии, где оно стало объединяющим фактором для некоторых индийских мусульман как одно из многих антибританских индийских политических движений. Его лидерами были Мохаммад Али Джухар , его брат Шаукат Али и Маулана Абул Калам Азад , доктор Мухтар Ахмед Ансари , Хаким Аджмал Хан и адвокат Мухаммад Джан Аббаси. Некоторое время его поддерживал Мохандас Карамчанд Ганди , который был членом Центрального комитета Халифата. [68] [69] Однако движение утратило свой импульс после упразднения халифата в 1924 году. После дальнейших арестов и бегства его лидеров, а также ряда ответвлений, отколовшихся от основной организации, движение в конечном итоге заглохло и распалось.

Шарифский халифат ( арабский : خلافة شريفية ) был арабским халифатом, провозглашенным шарифскими правителями Хиджаза в 1924 году, ранее известным как Вилайет Хиджаз , объявившим независимость от Османского халифата . Идея шарифского халифата витала по крайней мере с пятнадцатого века. [70] В арабском мире он представлял собой кульминацию долгой борьбы за возвращение халифата из рук Османской империи. Первые арабские восстания, оспаривавшие законность Османского халифата и требовавшие избрания арабского сейида халифом, можно проследить до 1883 года, когда шейх Хамат-ад-Дин захватил Сану и призвал к халифату в качестве сейида. [71]

Однако только после окончания Османского халифата , упраздненного кемалистами , Хусейн бин Али был провозглашен халифом в марте 1924 года. Его позиция по отношению к Османскому халифату была неоднозначной, и хотя он был враждебен к нему, [72] он предпочел дождаться его официального упразднения, прежде чем принять титул, чтобы не разбить Умму , создав второго халифа наряду с Османским халифом . Он также поддерживал финансово позднюю Османскую династию в изгнании, чтобы избежать их разорения. [73]

Его халифату противостояли Британская империя , сионисты и ваххабиты , [74] но он получил поддержку от значительной части мусульманского населения того времени, [75] [76] [77] [78] а также от Мехмеда VI . [79] Хотя он потерял Хиджаз и был сослан, а затем заключен в тюрьму англичанами на Кипре , [ 80] Хусейн продолжал использовать этот титул до своей смерти в 1931 году. [81] [82]

Хотя они и не являются политическими, некоторые суфийские ордена и движение Ахмадия [83] определяют себя как халифаты. Поэтому их лидеров обычно называют халифами (халифами).

В суфизме тарикатами (орденами) руководят духовные лидеры ( хилафа рухания ) , главные халифы, которые назначают местных халифов для организации зауйа . [84]

Суфийские халифаты не обязательно наследственные. Халифы призваны служить силсиле в отношении духовных обязанностей и распространять учения тариката.

Ахмадийская мусульманская община — самопровозглашённое исламское возрождающее движение, основанное в 1889 году Мирзой Гуламом Ахмадом из Кадиана , Индия, который утверждал, что он обещанный Мессия и Махди , которого ждут мусульмане. Он также утверждал, что является последователем- пророком, подчиненным Мухаммеду, пророку ислама. [ необходима цитата ] Группа традиционно избегается большинством мусульман. [85]

После смерти Ахмада в 1908 году его первый преемник, Хаким Нур-уд-Дин , стал халифом общины и принял титул Халифатуль Масих (Преемник или Халиф Мессии). [ требуется цитата ] После Хакима Нур-уд-Дина, первого халифа, титул ахмадийского халифа продолжился при Мирзе Махмуде Ахмаде , который руководил общиной более 50 лет. После него были Мирза Насир Ахмад и затем Мирза Тахир Ахмад , которые были третьим и четвертым халифами соответственно. [ требуется цитата ] Нынешним халифом является Мирза Масрур Ахмад , который живет в Лондоне. [86] [87]

Когда-то став предметом интенсивного конфликта и соперничества между мусульманскими правителями, халифат бездействовал и был в значительной степени невостребованным с 1920-х годов. Для большинства мусульман халиф, как лидер уммы , «лелеется и как память, и как идеал» [88] как время, когда мусульмане «пользовались научным и военным превосходством во всем мире». [89] Сообщается, что исламский пророк Мухаммед пророчествовал:

Пророчество останется с вами до тех пор, пока Аллах пожелает, чтобы оно оставалось, а затем Аллах возвысит его, когда пожелает возвысить его. После этого будет халифат, который следует руководству Пророчества, оставаясь с вами до тех пор, пока Аллах пожелает, чтобы оно оставалось. Затем Он возвысит его, когда пожелает возвысить его. После этого будет царствование жестокого угнетательного правления, и оно останется с вами до тех пор, пока Аллах пожелает, чтобы оно оставалось. Затем будет царствование тиранического правления, и оно останется до тех пор, пока Аллах пожелает, чтобы оно оставалось. Затем Аллах возвысит его, когда пожелает возвысить его. Затем будет халифат, следующий руководству Пророчества.

- Ас-Силсила Ас-Сахиха, т. 1, нет. 5

A contemporary effort to re-establish the caliphate by supporters of armed jihad that predates Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and the Islamic State and was much less successful, was "the forgotten caliphate" of Muhammad bin ʿIssa bin Musa al Rifaʿi ("known to his followers as Abu ʿIssa").[90] This "microcaliphate" was founded on 3 April 1993 on the Pakistan–Afghanistan border, when Abu Issa's small number of "Afghan Arabs" followers swore loyalty (bay'ah) to him.[91] Abu Issa, was born in the city of Zarqa, Jordan and like his followers had come to Afghanistan to wage jihad against the Soviets. Unlike them he had ancestors in the tribe of Quraysh, a traditional requirement for a caliph. The caliphate was ostensibly an attempt to unite the many other jihadis who were not his followers and who were quarrelling among each other. It was not successful.[92] Abu Issa's efforts to compel them to unite under his command were met "with mockery and then force". Local Afghans also despised him and his followers. Like the later Islamic State he tried to abolish infidel currency and rejected nationalism.[91] According to scholar Kevin Jackson,

Abu ʿIssa issued 'sad and funny' fatwas, as Abu al-Walid puts it, notably sanctioning the use of drugs. A nexus had been forged between [Abu Issa's group] and local drug smugglers. (The fatwa led one jihadist author to dismiss Abu Issa as the 'caliph of the Muslims among drug traffickers and takfir') Abu ʿIssa also prohibited the use of paper currency and ordered his men to burn their passports.[93]

The territory under his control "did not extend beyond a few small towns" in Afghanistan's Kunar province. Eventually he did not even control this area after the Taliban took it over in the late 1990s. The caliphate then moved to London, where they "preach[ed] to a mostly skeptical jihadi intelligentsia about the obligation of establishing a caliphate".[94] They succeeded in attracting some jihadis (Yahya al-Bahrumi, Abu Umar al Kuwaiti) who later joined the Islamic State. Abu Issa died in 2014, "after spending most of his final years in prison in London".[94] Abu Umar al Kuwaiti became a judge for the Islamic state but was later executed for extremism after he "took takfir to new levels ... pronouncing death sentences for apostasy on those who were ignorant of scripture – and then pronouncing takfir on those too reluctant to pronounce takfir."[95]

Ansar al-Sharia

Ansar al-Sharia  Islamic State

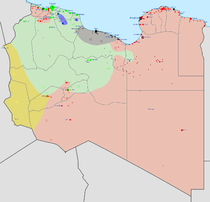

Islamic StateThe group Tanzim Qaidat al-Jihad fi Bilad al-Rafidayn (Al-Qaeda in Iraq) formed as an affiliate of Al-Qaeda network of Islamist militants during the Iraq War. The group eventually expanded into Syria and rose to prominence as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) during the Syrian Civil War. In the summer of 2014, the group launched the Northern Iraq offensive, seizing the city of Mosul.[96][97] The group declared itself a caliphate under Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi on 29 June 2014 and renamed itself as the "Islamic State".[98][99] ISIL's claim to be the highest authority of Muslims has been widely rejected.[100] No prominent Muslim scholar has supported its declaration of caliphate; even Salafi-jihadist preachers accused the group of engaging in political showmanship and bringing disrepute to the notion of Islamic state.[101]

ISIL has been at war with armed forces including the Iraqi Army, the Syrian Army, the Free Syrian Army, Al-Nusra Front, Syrian Democratic Forces, and Iraqi Kurdistan's Peshmerga and People's Protection Units (YPG) along with a 60 nation coalition in its efforts to establish a de facto state on Iraqi and Syrian territory.[102] At its height in 2014, the Islamic State held "about a third of Syria and 40 percent of Iraq". By December 2017 it had lost 95% of that territory, including Mosul, Iraq's second largest city, and the northern Syrian city of Raqqa, its "capital".[103] Its caliph, Al-Baghdadi, was killed in a raid by U.S. forces on 26 October 2019, its "last holdout", the town of Al-Baghuz Fawqani, fell to Syrian Democratic Forces on 23 March 2019.[103]

The members of the Ahmadiyya community believe that the Ahmadiyya Caliphate (Arabic: Khilāfah) is the continuation of the Islamic caliphate, first being the Rāshidūn (rightly guided) Caliphate (of Righteous Caliphs). This is believed to have been suspended with Ali, the son-in-law of Muhammad and re-established with the appearance of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908, the founder of the movement) whom Ahmadis identify as the Promised Messiah and Mahdi.

Ahmadis maintain that in accordance with Quranic verses (such as 24:55) and numerous ahadith on the issue, Khilāfah can only be established by God Himself and is a divine blessing given to those who believe and work righteousness and uphold the unity of God, therefore any movement to establish the Khilāfah centered on human endeavours alone is bound to fail, particularly when the condition of the people diverges from the ‘precepts of prophethood’ and they are as a result disunited, their inability to establish a Khilāfah caused fundamentally by the lack of righteousness in them. Although the khalifa is elected it is believed that God himself directs the hearts of believers towards an individual. Thus the khalifa is designated neither necessarily by right (i.e. the rightful or competent one in the eyes of the people at that time) nor merely by election but primarily by God.[104]

According to Ahmadiyya thought, a khalifa need not be the head of a state; rather the Ahmadiyya community emphasises the spiritual and organisational significance of the Khilāfah. It is primarily a religious/spiritual office, with the purpose of upholding, strengthening and spreading Islam and of maintaining the high spiritual and moral standards within the global community established by Muhammad – who was not merely a political leader but primarily a religious leader. If a khalifa does happen to bear governmental authority as a head of state, it is incidental and subsidiary in relation to his overall function as khalifa which is applicable to believers transnationally and not limited to one particular state.[105][106]

Ahmadi Muslims believe that God has assured them that this caliphate will endure to the end of time, depending on their righteousness and faith in God. The Khalifa provides unity, security, moral direction and progress for the community. It is required that the Khalifa carry out his duties through consultation and taking into consideration the views of the members of the Shura (consultative body). However, it is not incumbent upon him to always accept the views and recommendations of the members. The Khalifatul Masih has overall authority for all religious and organisational matters and is bound to decide and act in accordance with the Qur'an and sunnah.

A number of Islamist political parties and mujahideen called for the restoration of the caliphate by uniting Muslim nations, either through political action (e.g. Hizb ut-Tahrir), or through force (e.g. al-Qaeda).[107] Various Islamist movements gained momentum in recent years with the ultimate aim of establishing a caliphate. In 2014, ISIL/ISIS made a claim to re-establishing the caliphate. Those advocating the re-establishment of a caliphate differed in their methodology and approach. Some[who?] were locally oriented, mainstream political parties that had no apparent transnational objectives.[citation needed]

Abul A'la Maududi believed the caliph was not just an individual ruler who had to be restored, but was man's representation of God's authority on Earth:

Khilafa means representative. Man, according to Islam is the representative of "people", His (God's) viceregent; that is to say, by virtue of the powers delegated to him, and within the limits prescribed by the Qu'ran and the teaching of the prophet, the caliph is required to exercise Divine authority.[108]

The Muslim Brotherhood advocates pan-Islamic unity and the implementation of Islamic law. Founder Hassan al-Banna wrote about the restoration of the caliphate.[109]

One transnational group whose ideology was based specifically on restoring the caliphate as a pan-Islamic state is Hizb ut-Tahrir (literally, "Party of Liberation"). It is particularly strong in Central Asia and Europe and is growing in strength in the Arab world. It is based on the claim that Muslims can prove that God exists[110] and that the Qur'an is the word of God.[111][112] Hizb ut-Tahrir's stated strategy is a non-violent political and intellectual struggle.

In Southeast Asia, groups such as Jemaah Islamiyah aimed to establish a Caliphate across Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei and parts of Thailand, the Philippines and Cambodia.

Al-Qaeda has as one of its clearly stated goals the re-establishment of a caliphate.[113] Its former leader, Osama bin Laden, called for Muslims to "establish the righteous caliphate of our umma".[114] Al-Qaeda chiefs released a statement in 2005, under which, in what they call "phase five" there will be "an Islamic state, or caliphate".[115] Al-Qaeda has named its Internet newscast from Iraq "The Voice of the Caliphate".[116] According to author and Egyptian native Lawrence Wright, Ayman al-Zawahiri, bin Laden's mentor and al-Qaeda's second-in-command until 2011, once "sought to restore the caliphate... which had formally ended in 1924 following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire but which had not exercised real power since the thirteenth century." Zawahiri believes that once the caliphate is re-established, Egypt would become a rallying point for the rest of the Islamic world, leading the jihad against the West. "Then history would make a new turn, God willing", Zawahiri later wrote, "in the opposite direction against the empire of the United States and the world's Jewish government".[117]

Scholar Olivier Roy writes that "early on, Islamists replace the concept of the caliphate ... with that of the emir." There were a number of reasons including "that according to the classical authors, a caliph must be a member of the tribe of the Prophet (the Quraysh) ... moreover, caliphs ruled societies that the Islamists do not consider to have been Islamic (the Ottoman Empire)."[118] This is not the view of the majority of Islamist groups, as both the Muslim Brotherhood and Hizb ut-Tahrir view the Ottoman state as a caliphate.[119][120]

The Quran uses the term khalifa twice. First, in Surah Al-Baqara 2:30, it refers to God creating humanity as his khalifa on Earth. Second, in Surah Sad 38:26, it addresses King David as God's khalifa and reminds him of his obligation to rule with justice.[121]

In addition, the following excerpt from the Quran, known as the 'Istikhlaf Verse', is used by some to argue for a Quranic basis for a caliphate:

Allah has promised those of you who believe and do good that He will certainly make them successors in the land, as He did with those before them; and will surely establish for them their faith which He has chosen for them; and will indeed change their fear into security—˹provided that˺ they worship Me, associating nothing with Me. But whoever disbelieves after this ˹promise˺, it is they who will be the rebellious.

— Surah An-Nur 24:55

Several schools of jurisprudence and thought within Sunni Islam argue that to govern a state by Sharia is, by definition, to rule via the caliphate and use the following verses to sustain their claim.

And judge between them ˹O Prophet˺ by what Allah has revealed, and do not follow their desires. And beware, so they do not lure you away from some of what Allah has revealed to you. If they turn away ˹from Allah's judgment˺, then know that it is Allah's Will to repay them for some of their sins, and that many people are indeed rebellious.

— Surah Al-Ma'idah 5:49

O believers! Obey Allah and obey the Messenger and those in authority among you. Should you disagree on anything, then refer it to Allah and His Messenger, if you ˹truly˺ believe in Allah and the Last Day. This is the best and fairest resolution.

— Surah An-Nisa 4:59

The following hadith from Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal can be understood to prophesy two eras of the caliphate (both on the lines/precepts of prophethood).

Hadhrat Huzaifa narrated that the Messenger of Allah said: Prophethood will remain among you as long as Allah wills. Then Caliphate (Khilafah) on the lines of Prophethood shall commence, and remain as long as Allah wills. Then corrupt/erosive monarchy would take place, and it will remain as long as Allah wills. After that, despotic kingship would emerge, and it will remain as long as Allah wills. Then, the Caliphate (Khilafah) shall come once again based on the precept of Prophethood.[122][page needed]

In the above, the first era of the caliphate is commonly accepted by Muslims to be that of the Rashidun Caliphate.

Nafi'a reported saying:

It has been reported on the authority of Nafi, that 'Abdullah b. Umar paid a visit to Abdullah b. Muti' in the days (when atrocities were perpetrated on the People Of Medina) at Harra in the time of Yazid b. Mu'awiya. Ibn Muti' said: Place a pillow for Abu 'Abd al-Rahman (family name of 'Abdullah b. 'Umar). But the latter said: I have not come to sit with you. I have come to you to tell you a tradition I heard from the Messenger of Allah. I heard him say: One who withdraws his band from obedience (to the Amir) will find no argument (in his defence) when he stands before Allah on the Day of Judgment, and one who dies without having bound himself by an oath of allegiance (to an Amir) will die the death of one belonging to the days of Jahiliyyah.

— Sahih Muslim 1851a

Hisham ibn Urwah reported on the authority of Abu Saleh on the authority of Abu Hurairah that Muhammad said:

Leaders will take charge of you after me, where the pious (one) will lead you with his piety and the impious (one) with his impiety, so only listen to them and obey them in everything which conforms with the truth (Islam). If they act rightly it is for your credit, and if they acted wrongly it is counted for you and against them.

It has been narrated on the authority of Abu Huraira that the Prophet of Allah said:

A Imam is a shield for them. They fight behind him and they are protected by (him from tyrants and aggressors). If he enjoins fear of God, the Exalted and Glorious, and dispenses justice, there will be a (great) reward for him; and if he enjoins otherwise, it redounds on him.

— Sahih Muslim 1841

Narrated Abu Huraira:

The Prophet said, "The Israelis used to be ruled and guided by prophets: Whenever a prophet died, another would take over his place. There will be no prophet after me, but there will be Caliphs who will increase in number." The people asked, "O Allah's Messenger! What do you order us (to do)?" He said, "Obey the one who will be given the pledge of allegiance first. Fulfil their (i.e. the Caliphs) rights, for Allah will ask them about (any shortcoming) in ruling those Allah has put under their guardianship."

— Sahih al-Bukhari 3455

Many Islamic texts, including several ahadith, state that the Mahdi will be elected caliph and rule over a caliphate.[123] A number of Islamic figures titled themselves both "caliph" and "al-Mahdi", including the first Abbasid caliph As-Saffah.[124]

Al-Habbab Ibn ul-Munthir said, when the Sahaba met in the wake of the death of Muhammad, (at the thaqifa hall) of Bani Sa’ida:

Let there be one Amir from us and one Amir from you (meaning one from the Ansar and one from the Mohajireen).

Upon this Abu Bakr replied:

It is forbidden for Muslims to have two Amirs (rulers)...

Then he got up and addressed the Muslims.[125][126][127][128][129][130][page needed]

It has additionally been reported[131] that Abu Bakr went on to say on the day of Al-Saqifa:

It is forbidden for Muslims to have two Amirs for this would cause differences in their affairs and concepts, their unity would be divided and disputes would break out among them. The Sunnah would then be abandoned, the bida'a (innovations) would spread and Fitna would grow, and that is in no one's interests.

The Sahaba agreed to this and selected Abu Bakr as their first Khaleef. Habbab ibn Mundhir who suggested the idea of two Ameers corrected himself and was the first to give Abu Bakr the Bay'ah. This indicates an Ijma as-Sahaba of all of the Sahaba. Ali ibni abi Talib, who was attending the body of Muhammad at the time, also consented to this.

Imam Ali whom the Shia revere said:[132]

People must have an Amir...where the believer works under his Imara (rule) and under which the unbeliever would also benefit, until his rule ended by the end of his life (ajal), the booty (fay’i) would be gathered, the enemy would be fought, the routes would be made safe, the strong one will return what he took from the weak till the tyrant would be contained, and not bother anyone.

Scholars like Al-Mawardi,[133] Ibn Hazm,[134] Ahmad al-Qalqashandi,[135] and Al-Sha`rani[136] stated that the global Muslim community can have only one leader at any given time. Al-Nawawi[137] and Abd al-Jabbar ibn Ahmad[138] declared it impermissible to give oaths of loyalty to more than one leader.

Al-Joziri said:[139]

The Imams (scholars of the four schools of thought)- may Allah have mercy on them- agree that the Caliphate is an obligation, and that the Muslims must appoint a leader who would implement the injunctions of the religion, and give the oppressed justice against the oppressors. It is forbidden for Muslims to have two leaders in the world whether in agreement or discord.

Shia scholars have expressed similar opinions.[140][141][142][143] However, the Shia school of thought states that the leader must not be appointed by the Islamic ummah, but must be appointed by God.

Al-Qurtubi said that the caliph is the "pillar upon which other pillars rest", and said of the Quranic verse, "Indeed, man is made upon this earth a Caliph":[144][145]

This Ayah is a source in the selection of an Imaam, and a Khaleef, he is listened to and he is obeyed, for the word is united through him, and the Ahkam (laws) of the Caliph are implemented through him, and there is no difference regarding the obligation of that between the Ummah ...

An-Nawawi said:[146]

(The scholars) consented that it is an obligation upon the Muslims to select a Khalif

Al-Ghazali when writing of the potential consequences of losing the caliphate said:[147]

The judges will be suspended, the Wilayaat (provinces) will be nullified, ... the decrees of those in authority will not be executed and all the people will be on the verge of Haraam

Ibn Taymiyyah said[148][page needed]:

It is obligatory to know that the office in charge of commanding over the people (ie: the post of the Khaleefah) is one of the greatest obligations of the Deen. In fact, there is no establishment of the Deen except by it....this is the opinion of the salaf, such as Al-Fuḍayl ibn ‘Iyāḍ, Ahmad ibn Hanbal and others

In his book The Early Islamic Conquests (1981), Fred Donner argues that the standard Arabian practice during the early caliphates was for the prominent men of a kinship group, or tribe, to gather after a leader's death and elect a leader from among themselves, although there was no specified procedure for this shura, or consultative assembly. Candidates were usually from the same lineage as the deceased leader, but they were not necessarily his sons. Capable men who would lead well were preferred over an ineffectual direct heir, as there was no basis in the majority Sunni view that the head of state or governor should be chosen based on lineage alone. Since the Umayyads, all caliphates have been dynastic.

Traditionally, Sunni Muslim madhhabs all agreed that a caliph must be a descendant of the Quraysh.[149] Al-Baqillani has said that the leader of the Muslims simply should be from the majority.

Following the death of Muhammad, a meeting took place at Saqifah. At that meeting, Abu Bakr was elected caliph by the Muslim community. Sunni Muslims developed the belief that the caliph is a temporal political ruler, appointed to rule within the bounds of Islamic law (Sharia). The job of adjudicating orthodoxy and Islamic law was left to mujtahids, legal specialists collectively called the Ulama. Many Muslims call the first four caliphs the Rashidun, meaning the "Rightly Guided", because they are believed to have followed the Qur'an and the sunnah (example) of Muhammad.[citation needed]

With the exception of Zaidis,[150] Shi'ites believe in the Imamate, a principle by which rulers are imams who are divinely chosen, infallible and sinless and must come from the Ahl al-Bayt regardless of majority opinion, shura or election. They claim that before his death, Muhammad had given many indications, in the hadith of the pond of Khumm in particular, that he considered Ali, his cousin and son-in-law, as his successor. For the Twelvers, Ali and his eleven descendants, the Twelve Imams, are believed to have been considered, even before their birth, as the only valid Islamic rulers appointed and decreed by God. Shia Muslims believe that all the Muslim caliphs following Muhammad's death to be illegitimate due to their unjust rule and that Muslims have no obligation to follow them, as the only guidance that was left behind, as ordained in the hadith of the two weighty things, was the Islamic holy book, the Quran and Muhammad's family and offspring, who are believed to be infallible, therefore able to lead society and the Muslim community with complete justice and equity.[151][152][153][154] The Prophet's own grandson, and third Shia imam, Hussain ibn Ali led an uprising against injustice and the oppressive rule of the Muslim caliph at the time at the Battle of Karbala. Shia Muslims emphasise that values of social justice, and speaking out against oppression and tyranny are not merely moral values, but values essential to a person's religiosity.[155][156][157][152][158]

After these Twelve Imams, the potential caliphs, had passed, and in the absence of the possibility of a government headed by their imams, some Twelvers believe it was necessary that a system of Shi'i Islamic government based on the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist be developed, due to the need for some form of government, where an Islamic jurist or faqih rules Muslims, suffices. However, this idea, developed by the marja' Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and established in Iran, is not universally accepted among the Shia.

Ismailis believe in the Imamate principle mentioned above, but they need not be secular rulers as well.

The Majlis al-Shura (literally "consultative assembly") was a representation of the idea of consultative governance. The importance of this is premised by the following verses of the Qur'an:

The majlis is also the means to elect a new caliph.[159] Al-Mawardi has written that members of the majlis should satisfy three conditions: they must be just, have enough knowledge to distinguish a good caliph from a bad one and have sufficient wisdom and judgement to select the best caliph. Al-Mawardi also said that in emergencies when there is no caliphate and no majlis, the people themselves should create a majlis and select a list of candidates for caliph; then the majlis should select a caliph from the list of candidates.[159]

Some Islamist interpretations of the role of the Majlis al-Shura are the following: In an analysis of the shura chapter of the Qur'an, Islamist author Sayyid Qutb argues that Islam only requires the ruler to consult with some of the representatives of the ruled and govern within the context of the Sharia. Taqiuddin al-Nabhani, the founder of a transnational political movement devoted to the revival of the caliphate, writes that although the Shura is an important part of "the ruling structure" of the Islamic caliphate, "(it is) not one of its pillars", meaning that its neglect would not make a caliph's rule un-Islamic such as to justify a rebellion. However, the Muslim Brotherhood, the largest Islamic movement in Egypt, has toned down these Islamist views by accepting in principle that in the modern age the Majlis al-Shura is democracy.

Al-Mawardi said that if the rulers meet their Islamic responsibilities to the public the people must obey their laws, but a caliph or ruler who becomes either unjust or severely ineffective must be impeached via the Majlis al-Shura. Al-Juwayni argued that Islam is the goal of the ummah, so any ruler who deviates from this goal must be impeached. Al-Ghazali believed that oppression by a caliph is sufficient grounds for impeachment. Rather than just relying on impeachment, Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani stated that the people have an obligation to rebel if the caliph begins to act with no regard for Islamic law. Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani said that to ignore such a situation is haraam and those who cannot revolt from inside the caliphate should launch a struggle from outside. Al-Asqalani used two ayahs from the Qur'an to justify this:

And they (the sinners on qiyama) will say, "Our Lord! We obeyed our leaders and elite, but they led us astray from the ˹Right˺ Way. Our Lord! Give them double ˹our˺ punishment, and condemn them tremendously."

— Surah Al-Ahzab 33:67–68

Islamic lawyers commented that when the rulers refuse to step down after being impeached through the Majlis, becoming dictators through the support of a corrupt army, if the majority is in agreement they have the option to launch a revolution. Many noted that this option is to be exercised only after factoring in the potential cost of life.[159]

The following hadith establishes the principle of rule of law in relation to nepotism and accountability[160][non-primary source needed]

Narrated ‘Aisha: The people of Quraish worried about the lady from Bani Makhzum who had committed theft. They asked, "Who will intercede for her with Allah's Apostle?" Some said, "No one dare to do so except Usama bin Zaid the beloved one to Allah's Apostle." When Usama spoke about that to Allah's Apostle; Allah's Apostle said: "Do you try to intercede for somebody in a case connected with Allah’s Prescribed Punishments?" Then he got up and delivered a sermon saying, "What destroyed the nations preceding you, was that if a noble amongst them stole, they would forgive him, and if a poor person amongst them stole, they would inflict Allah's Legal punishment on him. By Allah, if Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad (my daughter) stole, I would cut off her hand."

Various Islamic lawyers, however, place multiple conditions and stipulations on the execution of such a law, making it difficult to implement. For example, the poor cannot be penalised for stealing out of poverty, and during a time of drought in the Rashidun caliphate, capital punishment was suspended until the effects of the drought passed.[161]

Islamic jurists later formulated the concept that all classes were subject to the law of the land, and no person is above the law; officials and private citizens alike have a duty to obey the same law. Furthermore, a Qadi (Islamic judge) was not allowed to discriminate on the grounds of religion, race, colour, kinship or prejudice. In a number of cases, caliphs had to appear before judges as they prepared to render their verdict.[162]

According to Noah Feldman, a law professor at Harvard University, the system of legal scholars and jurists responsible for the rule of law was replaced by the codification of Sharia by the Ottoman Empire in the early nineteenth century:[163]

During the Muslim Agricultural Revolution, the caliphate understood that real incentives were needed to increase productivity and wealth and thus enhance tax revenues. A social transformation took place as a result of changing land ownership[164] giving individuals of any gender,[165] ethnic or religious background the right to buy, sell, mortgage and inherit land for farming or any other purpose. Signatures were required on contracts for every major financial transaction concerning agriculture, industry, commerce and employment. Copies of the contract were usually kept by both parties involved.[164]

Early forms of proto-capitalism and free markets were present in the caliphate,[166] since an early market economy and early form of merchant capitalism developed between the 8th and 12th centuries, which some refer to as "Islamic capitalism".[167] A vigorous monetary economy developed based on the circulation of a stable high-value currency (the dinar) and the integration of previously independent monetary areas. Business techniques and forms of business organisation employed during this time included early contracts, bills of exchange, long-distance international trade, early forms of partnership (mufawada) such as limited partnerships (mudaraba) and early forms of credit, debt, profit, loss, capital (al-mal), capital accumulation (nama al-mal),[168] circulating capital, capital expenditure, revenue, cheques, promissory notes,[169] trusts (waqf), startup companies,[170] savings accounts, transactional accounts, pawning, loaning, exchange rates, bankers, money changers, ledgers, deposits, assignments, the double-entry bookkeeping system,[171] and lawsuits.[172] Organisational enterprises similar to corporations independent from the state also existed in the medieval Islamic world.[173][174] Many of these concepts were adopted and further advanced in medieval Europe from the thirteenth century onwards.[168]

Early Islamic law included collection of Zakat (charity), one of the Five Pillars of Islam, since the time of the first Islamic State, established by Muhammad at Medina. The taxes (including Zakat and Jizya) collected in the treasury (Bayt al-mal) of an Islamic government were used to provide income for the needy, including the poor, elderly, orphans, widows and the disabled. During the caliphate of Abu Bakr, a number of the Arab tribes, who had accepted Islam at the hand of The Prophet Muhammad, rebelled and refused to continue to pay the Zakat, leading to the Ridda Wars. Caliph Umar added to the duties of the state an allowance, paid on behalf of every man woman and child, starting at birth, creating the world's first state run social welfare program.

Maya Shatzmiller states that the demographic behaviour of medieval Islamic society varied in some significant respects from other agricultural societies. Nomadic groups within places like the deserts of Egypt and Morocco maintained high birth rates compared to rural and urban populations, though periods of extremely high nomadic birth rates seem to have occurred in occasional "surges" rather than on a continuous basis. Individuals living in large cities had much lower birth rates, possibly due to the use of birth control methods and political or economic instability. This led to population declines in some regions.[175] While several studies have shown that Islamic scholars enjoyed a life expectancy of 59–75 years between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries,[176][177][178] the overall life expectancy of men in the same societies was lower.[179] Factoring in infant mortality, Lawrence Conrad estimates the average lifespan in the early Islamic caliphate to be above 35 years for the general population, compared to around 40 years for the population of Classical Greece[180] and 31 years for the population of thirteenth-century England.[181]

The early Islamic Empire also had the highest literacy rates among pre-modern societies, alongside the city of classical Athens in the fourth century BC,[182] and later, China after the introduction of printing from the tenth century.[183] One factor for the relatively high literacy rates in the early Islamic Empire was its parent-driven educational marketplace, as the state did not systematically subsidise educational services until the introduction of state funding under Nizam al-Mulk in the eleventh century.[184] Another factor was the diffusion of paper from China,[185] which led to an efflorescence of books and written culture in Islamic society; thus papermaking technology transformed Islamic society (and later, the rest of Afro-Eurasia) from an oral to scribal culture, comparable to the later shifts from scribal to typographic culture, and from typographic culture to the Internet.[186] Other factors include the widespread use of paper books in Islamic society (more so than any other previously existing society), the study and memorisation of the Qur'an, flourishing commercial activity and the emergence of the Maktab and Madrasah educational institutions.[187]

Today the term 'caliphate' has come to denote in journalistic use a form of political and religious tyranny, a fanatical version of the application of Islamic law, and a general intolerence toward other faiths – another interpretation, albeit a distorted one, at the beginning of the twenty-first century. It may be useful to recall that such radical perceptions of the term float mostly in the realm of media coverage and are far removed from the actual historical reality of the achievements when a caliphate existed in the medieval period. If we take a longer view of the influence of the office of the caliphate on changes in Islamic society, it may be worth noting that most of the dramatic social and legal reforms instituted by, for instance, the Ottomans in the 19th century were only feasible because of the ability of the sultan to posture as caliph. The Gulhane Reform of 1839 which established the equality of all subjects of the empire before the law, the reforms of 1856 which eliminated social distinctions based on religion, the abolition of slavery in 1857, and the suspension of the traditional penalties of Islamic law in 1858 would all have been inconceivable without the clout that the umbrella of the caliphate afforded to the office of the reforming monarch.

In the course of the later eleventh and twelfth century, however, the Fatimid caliphate declined rapidly, and in 1171 the country was invaded by Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn, the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. He restored Egypt as a political power, reincorporated it in the Abbasid caliphate and established Ayyubid suzerainty not only over Egypt and Syria but, as mentioned above, temporarily over northern Mesopotamia as well.

Rejected by the majority of Muslims as heretical since it believes in ongoing prophethood after the death of Muhammad. Currently based in Pakistan, but forbidden to practice, preach, or propagate their faith as Islam or their places of worship as mosques.

Life expectancy was another area where Islamic society diverged from the suggested model for agricultural society. No less than three separate studies about the life expectancy of religious scholars, two from 11th century Muslim Spain, and one from the Middle East, concluded that members of this occupational group enjoyed a life expectancy of 69, 75, and 72.8 years respectively!

This rate is uncommonly high, not only under the conditions in medieval cities, where these 'ulama' lived, but also in terms of the average life expectancy for contemporary males. [...] In other words, the social group studied through the biographies is, a priori, a misleading sample, since it was composed exclusively of individuals who enjoyed exceptional longevity.

Reaching further back through the centuries, the civilisations regarded as having the highest literacy rates of their ages were parent-driven educational marketplaces. The ability to read and write was far more widely enjoyed in the early medieval Islamic empire and in fourth-century-B.C.E. Athens than in any other cultures of their times.

The spread of written knowledge was at least the equal of what it was in China after printing became common there in the tenth century. (Chinese books were printed in small editions of a hundred or so copies.)

In neither case did the state supply or even systematically subsidise educational services. The Muslim world's eventual introduction of state funding under Nizam al-Mulk in the eleventh century was quickly followed by partisan religious squabbling over education and the gradual fall of Islam from its place of cultural and scientific preeminence.

According to legend, paper came to the Islamic world as a result of the capture of Chinese paper makers at the 751 C.E. battle of Talas River.

Whatever the source, the diffusion of paper-making technology via the lands of Islam produced a shift from oral to scribal culture across the rest of Afroeurasia that was rivalled only by the move from scribal to typographic culture. (Perhaps it will prove to have been even more important than the recent move from typographic culture to the Internet.) The result was remarkable. As historian Jonathan Bloom informs us, paper encouraged "an efflorescence of books and written culture incomparably more brilliant than was known anywhere in Europe until the invention of printing with movable type in the fifteenth century.

More so than any previously existing society, Islamic society of the period 1000–1500 was profoundly a culture of books. [...] The emergence of a culture of books is closely tied to cultural dispositions toward literacy in Islamic societies. Muslim young men were encouraged to memorise the Qur'an as part of their transition to adulthood, and while most presumably did not (though little is known about literacy levels in pre-Mongol Muslim societies), others did. Types of literacy in any event varied, as Nelly Hanna has recently suggested, and are best studied as part of the complex social dynamics and contexts of individual Muslim societies. The need to conform commercial contracts and business arrangements to Islamic law provided a further impetus for literacy, especially likely in commercial centers. Scholars often engaged in commercial activity and craftsmen or tradesmen often spent time studying in madrasas. The connection between what Brian Street has called "maktab literacy" and commercial literacy was real and exerted a steady pressure on individuals to upgrade their reading skills.