Heaven, or the heavens, is a common religious cosmological or transcendent supernatural place where beings such as deities, angels, souls, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate, be enthroned, or reside. According to the beliefs of some religions, heavenly beings can descend to Earth or incarnate and earthly beings can ascend to Heaven in the afterlife or, in exceptional cases, enter Heaven without dying.

Heaven is often described as a "highest place", the holiest place, a paradise, in contrast to hell or the underworld or the "low places" and universally or conditionally accessible by earthly beings according to various standards of divinity, goodness, piety, faith, or other virtues or right beliefs or simply divine will. Some believe in the possibility of a heaven on Earth in a world to come.

Another belief is in an axis mundi or world tree which connects the heavens, the terrestrial world, and the underworld. In Indian religions, heaven is considered as Svargaloka,[1] and the soul is again subjected to rebirth in different living forms according to its karma. This cycle can be broken after a soul achieves Moksha or Nirvana. Any place of existence, either of humans, souls or deities, outside the tangible world (Heaven, Hell, or other) is referred to as the otherworld.

At least in the Abrahamic faiths of Christianity, Islam, and some schools of Judaism, as well as Zoroastrianism, heaven is the realm of afterlife where good actions in the previous life are rewarded for eternity (hell being the place where bad behavior is punished).

The modern English word heaven is derived from the earlier (Middle English) heven (attested 1159); this in turn was developed from the previous Old English form heofon. By about 1000, heofon was being used in reference to the Christianized "place where God dwells", but originally, it had signified "sky, firmament"[2] (e.g. in Beowulf, c. 725).

The English term has cognates in the other Germanic languages: Old Saxon heƀan "sky, heaven" (hence also Middle Low German heven "sky"), Old Icelandic himinn, Gothic himins; and those with a variant final -l: Old Frisian himel, himul "sky, heaven", Old Saxon and Old High German himil, Old Saxon and Middle Low German hemmel, Old Dutch and Dutch hemel, and modern German Himmel. All of these have been derived from a reconstructed Proto-Germanic form *hemina-.[3] or *hemō.[4]

The further derivation of this form is uncertain. A connection to Proto-Indo-European *ḱem- "cover, shroud", via a reconstructed *k̑emen- or *k̑ōmen- "stone, heaven", has been proposed.[5]

Others endorse the derivation from a Proto-Indo-European root *h₂éḱmō "stone" and, possibly, "heavenly vault" at the origin of this word, which then would have as cognates ancient Greek ἄκμων (ákmōn "anvil, pestle; meteorite"), Persian آسمان (âsemân, âsmân "stone, sling-stone; sky, heaven") and Sanskrit अश्मन् (aśman "stone, rock, sling-stone; thunderbolt; the firmament").[4] In the latter case English hammer would be another cognate to the word.

The ancient Mesopotamians regarded the sky as a series of domes (usually three, but sometimes seven) covering the flat Earth.[8] Each dome was made of a different kind of precious stone.[9] The lowest dome of heaven was made of jasper and was the home of the stars.[10][11] The middle dome of heaven was made of saggilmut stone and was the abode of the Igigi.[10][11] The highest and outermost dome of heaven was made of luludānītu stone and was personified as An, the god of the sky.[12][10][11] The celestial bodies were equated with specific deities as well.[9] The planet Venus was believed to be Inanna, the goddess of sex and war.[13][9] The Sun was her brother Utu, the god of justice, and the Moon was their father Nanna.[9]

In ancient Near Eastern cultures in general and in Mesopotamia in particular, humans had little to no access to the divine realm.[14][15] Heaven and Earth were separated by their very nature;[11] humans could see and be affected by elements of the lower heaven, such as stars and storms,[11] but ordinary mortals could not go to Heaven because it was the abode of the gods alone.[15][16][11] In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh says to Enkidu, "Who can go up to heaven, my friend? Only the gods dwell with Shamash forever."[16] Instead, after a person died, his or her soul went to Kur (later known as Irkalla), a dark shadowy underworld, located deep below the surface of the earth.[15][17]

All souls went to the same afterlife,[15][17] and a person's actions during life had no impact on how he would be treated in the world to come.[15][17] Nonetheless, funerary evidence indicates that some people believed that Inanna had the power to bestow special favors upon her devotees in the afterlife.[17][18] Despite the separation between heaven and earth, humans sought access to the gods through oracles and omens.[6] The gods were believed to live in Heaven,[6][19] but also in their temples, which were seen as the channels of communication between Earth and Heaven, which allowed mortal access to the gods.[6][20] The Ekur temple in Nippur was known as the "Dur-an-ki", the "mooring rope" of heaven and earth.[21] It was widely thought to have been built and established by Enlil himself.[7]

The ancient Hittites believed that some deities lived in Heaven while others lived in remote places on Earth, such as mountains, where humans had little access.[14] In the Middle Hittite myths, Heaven is the abode of the gods. In the Song of Kumarbi, Alalu was king in Heaven for nine years before giving birth to his son, Anu. Anu was himself overthrown by his son, Kumarbi.[22][23][24][25]

Almost nothing is known of Bronze Age (pre-1200 BC) Canaanite views of heaven and the archaeological findings at Ugarit (destroyed c. 1200 BC) have not provided information. The first century Greek author Philo of Byblos may have preserved elements of Iron Age Phoenician religion in his Sanchuniathon.[26]

Zoroaster, the Zoroastrian prophet who introduced the Gathas, spoke of the existence of Heaven and Hell.[27][28]

Historically, the unique features of Zoroastrianism, such as its conception of heaven, hell, angels, monotheism, belief in free will, and the day of judgement, among other concepts, may have influenced other religious and philosophical systems, including the Abrahamic religions, Gnosticism, Northern Buddhism, and Greek philosophy.[29][28]

As in other ancient Near Eastern cultures, in the Hebrew Bible, the universe is commonly divided into two realms: heaven (šāmayim) and earth (’ereṣ).[6] Sometimes a third realm is added: either "sea",[30] "water under the earth",[31] or sometimes a vague "land of the dead" that is never described in depth.[32][6] The structure of heaven itself is not fully described in the Hebrew Bible,[33] but the fact that the Hebrew word šāmayim is plural has been interpreted by scholars as an indication that the ancient Israelites envisioned the heavens as having multiple layers, much like the ancient Mesopotamians.[33] This reading is also supported by the use of the phrase "heaven of heavens" in verses such as Deuteronomy 10:14,[34] 1 Kings 8:27,[35] and 2 Chronicles 2:6.[36][33]

In line with the typical view of most Near Eastern cultures, the Hebrew Bible depicts Heaven as a place that is inaccessible to humans.[37] Although some prophets are occasionally granted temporary visionary access to heaven, such as in 1 Kings 22:19–23,[38] Job 1:6–12[39] and 2:1–6,[40] and Isaiah 6,[41] they hear only God's deliberations concerning the Earth and learn nothing of what Heaven is like.[33] There is almost no mention in the Hebrew Bible of Heaven as a possible afterlife destination for human beings, who are instead described as "resting" in Sheol.[42][43] The only two possible exceptions to this are Enoch, who is described in Genesis 5:24[44] as having been "taken" by God, and the prophet Elijah, who is described in 2 Kings 2:11[45] as having ascended to Heaven in a chariot of fire.[33] According to Michael B. Hundley, the text in both of these instances is ambiguous regarding the significance of the actions being described[33] and in neither of these cases does the text explain what happened to the subject afterwards.[33]

The God of the Israelites is described as ruling both Heaven and Earth.[46][33] Other passages, such as 1 Kings 8:27[35] state that even the vastness of Heaven cannot contain God's majesty.[33] A number of passages throughout the Hebrew Bible indicate that Heaven and Earth will one day come to an end.[47][33] This view is paralleled in other ancient Near Eastern cultures, which also regarded Heaven and Earth as vulnerable and subject to dissolution.[33] However, the Hebrew Bible differs from other ancient Near Eastern cultures in that it portrays the God of Israel as independent of creation and unthreatened by its potential destruction.[33] Because most of the Hebrew Bible concerns the God of Israel's relationship with his people, most of the events described in it take place on Earth, not in Heaven.[48] The Deuteronomistic source, Deuteronomistic History, and Priestly source all portray the Temple in Jerusalem as the sole channel of communication between Earth and Heaven.[49]

During the period of the Second Temple (c. 515 BC – 70 AD), the Hebrew people lived under the rule of first the Persian Achaemenid Empire, then the Greek kingdoms of the Diadochi, and finally the Roman Empire.[50] Their culture was profoundly influenced by those of the peoples who ruled them.[50] Consequently, their views on existence after death were profoundly shaped by the ideas of the Persians, Greeks, and Romans.[51][52] The idea of the immortality of the soul is derived from Greek philosophy[52] and the idea of the resurrection of the dead is thought to be derived from Persian cosmology,[52] although the later claim has been recently questioned.[53] By the early first century AD, these two seemingly incompatible ideas were often conflated by Hebrew thinkers.[52] The Hebrews also inherited from the Persians, Greeks, and Romans the idea that the human soul originates in the divine realm and seeks to return there.[50] The idea that a human soul belongs in Heaven and that Earth is merely a temporary abode in which the soul is tested to prove its worthiness became increasingly popular during the Hellenistic period (323–31 BC).[43] Gradually, some Hebrews began to adopt the idea of Heaven as the eternal home of the righteous dead.[43]

Descriptions of Heaven in the New Testament are more fully developed than those in the Old Testament, but are still generally vague.[54] As in the Old Testament, in the New Testament God is described as the ruler of Heaven and Earth, but his power over the Earth is challenged by Satan.[43] The Gospels of Mark and Luke speak of the "Kingdom of God" (‹See Tfd›Greek: βασιλεία τοῦ θεοῦ; basileía tou theou), while the Gospel of Matthew more commonly uses the term "Kingdom of heaven" (‹See Tfd›Greek: βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν; basileía tōn ouranōn).[55][56][57][43] Both phrases are thought to have the same meaning,[58] but the author of the Gospel of Matthew changed the name "Kingdom of God" to "Kingdom of Heaven" in most instances because it was the more acceptable phrase in his own cultural and religious context in the late first century.[59]

Modern scholars agree that the Kingdom of God was an essential part of the teachings of the historical Jesus[60][61] but there is no agreement on what this kingdom was.[62][63] None of the gospels record Jesus as having explained exactly what the phrase "Kingdom of God" means.[61] The most likely explanation for this apparent omission is that the Kingdom of God was a commonly understood concept that required no explanation.[61]

According to Sanders and Casey, Jews in Judea during the early first century believed that God reigns eternally in Heaven,[60][64] but many also believed that God would eventually establish his kingdom on earth as well.[60][65] Because God's Kingdom was believed to be superior to any human kingdom, this meant that God would necessarily drive out the Romans, who ruled Judea, and establish his own direct rule over the Jewish people.[55][65] This belief is referenced in the first petition of the Lord's Prayer, taught by Jesus to his disciples and recorded in Matthew[66] and Luke 11:2:[67] "Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven."[68][69]

Other scholars contend that Jesus' teaching of the Kingdom of God was of something that is present but also still yet to come.[70] For instance, Wright points to the synoptic gospels that Jesus' death and resurrection was anticipated as the climax and fulfillment of his "Kingdom of God" messages and that his combined prophecy about the temple's doom, through apocalyptic language, would serve as his vindication.[71] The synoptic gospels and Pauline epistles portray Jesus as believing his death and resurrection would complete the work of inaugurating the Kingdom of God and that his followers who wrote everything down expressed their belief he had done so, using first-century Jewish idioms, and that such events "did with evil and launch the project of new creation".[72]

In the teachings of the historical Jesus, people are expected to prepare for the coming of the Kingdom of God by living moral lives.[73] Jesus's commands for his followers to adopt lifestyles of moral perfectionism are found in many passages throughout the Synoptic Gospels, particularly in the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5–7.[74][75] Jesus also taught that, in the Kingdom of Heaven, there would be a reversal of roles in which "the last will be first and the first will be last."[76][77] This teaching recurs throughout the recorded teachings of Jesus, including in the admonition to be like a child,[78] the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus in Luke 16,[79] the Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard in Matthew 20,[80] the Parable of the Great Banquet in Matthew 22,[81] and the Parable of the Prodigal Son in Luke 15.[82][83]

Traditionally, Christianity has taught that Heaven is the location of the throne of God as well as the holy angels,[84][85] although this is in varying degrees considered metaphorical. In traditional Christianity, it is considered a state or condition of existence (rather than a particular place somewhere in the cosmos) of the supreme fulfillment of theosis in the beatific vision of the Godhead. In most forms of Christianity, Heaven is also understood as the abode for the redeemed dead in the afterlife, usually a temporary stage before the resurrection of the dead and the saints' return to the New Earth.

The resurrected Jesus is said to have ascended to Heaven where he now sits at the Right Hand of God and will return to Earth in the Second Coming. Various people have been said to have entered Heaven while still alive, including Enoch, Elijah and Jesus, after his resurrection. According to Roman Catholic teaching, Mary, mother of Jesus, is also said to have been assumed into Heaven and is titled the Queen of Heaven.

In the second century AD, Irenaeus of Lyons recorded a belief that, in accordance with John 14,[86] those who in the afterlife see the Saviour are in different mansions, some dwelling in the heavens, others in paradise and others in "the city".[87]

While the word used in all these writings, in particular the New Testament Greek word οὐρανός (ouranos), applies primarily to the sky, it is also used metaphorically of the dwelling place of God and the blessed.[88][89] Similarly, though the English word "heaven" keeps its original physical meaning when used, for instance, in allusions to the stars as "lights shining through from heaven", and in phrases such as heavenly body to mean an astronomical object, the heaven or happiness that Christianity looks forward to is, according to Pope John Paul II, "neither an abstraction nor a physical place in the clouds, but a living, personal relationship with the Holy Trinity. It is our meeting with the Father which takes place in the risen Christ through the communion of the Holy Spirit."[84]

While the concept of Heaven (malkuth hashamaim מלכות השמים, the Kingdom of Heaven) is much discussed in Christian thought, the Jewish concept of the afterlife, sometimes known as olam haba, the World-to-come, is not discussed as often. The Torah has little to say on the subject of survival after death, but by the time of the rabbis two ideas had made inroads among the Jews: one, which is probably derived from Greek thought,[90] is that of the immortal soul which returns to its creator after death; the other, which is thought to be of Persian origin,[90] is that of resurrection of the dead.

Jewish writings[which?] refer to a "new earth" as the abode of mankind following the resurrection of the dead. Originally, the two ideas of immortality and resurrection were different but in rabbinic thought they are combined: the soul departs from the body at death but is returned to it at the resurrection. This idea is linked to another rabbinic teaching, that men's good and bad actions are rewarded and punished not in this life but after death, whether immediately or at the subsequent resurrection.[90] Around 1 CE, the Pharisees believed in an afterlife but the Sadducees did not.[91]

The Mishnah has many sayings about the World to Come, for example, "Rabbi Yaakov said: This world is like a lobby before the World to Come; prepare yourself in the lobby so that you may enter the banquet hall."[92]

Judaism holds that the righteous of all nations have a share in the World-to-come.[93]

According to Nicholas de Lange, Judaism offers no clear teaching about the destiny which lies in wait for the individual after death and its attitude to life after death has been expressed as follows: "For the future is inscrutable, and the accepted sources of knowledge, whether experience, or reason, or revelation, offer no clear guidance about what is to come. The only certainty is that each man must die – beyond that we can only guess."[90]

Similar to Jewish traditions such as the Talmud, the Qur'an and Hadith frequently mention the existence of seven samāwāt (سماوات), the plural of samāʾ (سماء), meaning 'heaven, sky, celestial sphere', and cognate with Hebrew shamāyim (שמים). Some of the verses in the Qur'an mentioning the samaawat [94] are 41:12, 65:12 and 71:15. Sidrat al-Muntaha, a large enigmatic Lote tree, marks the end of the seventh heaven and the utmost extremity for all of God's creatures and heavenly knowledge.[95]

One interpretation of "heavens" is that all the stars and galaxies (including the Milky Way) are part of the "first heaven", and "beyond that six still bigger worlds are there," which have yet to be discovered by scientists.[96]

According to Shi'ite sources, Ali mentioned the names of the seven heavens as below:[97]

Still an afterlife destination of the righteous is conceived in Islam as Jannah (Arabic: جنة "Garden [of Eden]" translated as "paradise"). Regarding Eden or paradise the Quran says, "The description of the Paradise promised to the righteous is that under it rivers flow; eternal is its fruit as well as its shade. That is the ˹ultimate˺ outcome for the righteous. But the outcome for the disbelievers is the Fire!"[98] Islam rejects the concept of original sin, and Muslims believe that all human beings are born pure. Children automatically go to paradise when they die, regardless of the religion of their parents.

Paradise is described primarily in physical terms as a place where every wish is immediately fulfilled when asked. Islamic texts describe immortal life in Jannah as happy, without negative emotions. Those who dwell in Jannah are said to wear costly apparel, partake in exquisite banquets, and recline on couches inlaid with gold or precious stones. Inhabitants will rejoice in the company of their parents, spouses, and children. In Islam if one's good deeds outweigh one's sins then one may gain entrance to paradise only through God's mercy. Conversely, if one's sins outweigh their good deeds they are sent to hell. The more good deeds one has performed the higher the level of Jannah one is directed to.

Quran verses which describe paradise include: 13:15, 18:31, 38:49–54, 35:33–35 and 52:17.[99]

The Quran refers to Jannah with different names: Al-Firdaws, Jannātu-′Adn ("Garden of Eden" or "Everlasting Gardens"), Jannatu-n-Na'īm ("Garden of Delight"), Jannatu-l-Ma'wa ("Garden of Refuge"), Dāru-s-Salām ("Abode of Peace"), Dāru-l-Muqāma ("Abode of Permanent Stay"), al-Muqāmu-l-Amin ("The Secure Station") and Jannātu-l-Khuld ("Garden of Immortality"). In the Hadiths, these are the different regions in paradise.[100]

According to the Ahmadiyya view, much of the imagery presented in the Quran regarding Heaven, but also Hell, is metaphorical. They propound the verse which describes, according to them, how the life to come after death is different from the life on Earth. The Quran says: "From bringing in your place others like you, and from developing you into a form which at present you know not."[101] According to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of the Ahmadiyya sect in Islam, the soul will give birth to another rarer entity and will resemble the life on earth in the sense that this entity will bear a similar relationship to the soul, as the soul bears relationship with the human existence on earth. On earth, if a person leads a righteous life and submits to the will of God, his or her tastes become attuned to enjoying spiritual pleasures as opposed to carnal desires. With this, an "embryonic soul" begins to take shape. Different tastes are said to be born in which a person given to carnal passions finds no enjoyment. For example, sacrifice of one's own rights over that of other's becomes enjoyable, or that forgiveness becomes second nature. In such a state a person finds contentment and Peace at heart and at this stage, according to Ahmadiyya beliefs, it can be said that a soul within the soul has begun to take shape.[102]

The Baháʼí Faith regards the conventional description of heaven (and hell) as a specific place as symbolic. The Baháʼí writings describe heaven as a "spiritual condition" where closeness to God is defined as heaven; conversely hell is seen as a state of remoteness from God. Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, has stated that the nature of the life of the soul in the afterlife is beyond comprehension in the physical plane, but has stated that the soul will retain its consciousness and individuality and remember its physical life; the soul will be able to recognize other souls and communicate with them.[103]

For Baháʼís, entry into the next life has the potential to bring great joy.[103] Bahá'u'lláh likened death to the process of birth. He explains: "The world beyond is as different from this world as this world is different from that of the child while still in the womb of its mother."[104] The analogy to the womb in many ways summarizes the Baháʼí view of earthly existence: just as the womb constitutes an important place for a person's initial physical development, the physical world provides for the development of the individual soul. Accordingly, Baháʼís view life as a preparatory stage, where one can develop and perfect those qualities which will be needed in the next life.[103] The key to spiritual progress is to follow the path outlined by the current Manifestation of God, which Baháʼís believe is currently Bahá'u'lláh. Bahá'u'lláh wrote, "Know thou, of a truth, that if the soul of man hath walked in the ways of God, it will, assuredly return and be gathered to the glory of the Beloved."[105]

The Baháʼí teachings state that there exists a hierarchy of souls in the afterlife, where the merits of each soul determines their place in the hierarchy, and that souls lower in the hierarchy cannot completely understand the station of those above. Each soul can continue to progress in the afterlife, but the soul's development is not entirely dependent on its own conscious efforts, the nature of which we are not aware, but also augmented by the grace of God, the prayers of others, and good deeds performed by others on Earth in the name of that person.[103]

Mandaeans believe in an afterlife or heaven called Alma d-Nhura (World of Light).[106] The World of Light is the primeval, transcendent world from which Tibil and the World of Darkness emerged. The Great Living God (Hayyi Rabbi) and his uthras (angels or guardians) dwell in the World of Light. The World of Light is also the source of Piriawis, the Great Yardena (or Jordan River) of Life.[107]

The cosmological description of the universe in the Gnostic codex On the Origin of the World presents seven heavens created by the lesser god or Demiurge called Yaldabaoth, which are individually ruled over by one of his Archons. Above these realms is the eighth heaven, where the benevolent, higher divinities dwell. During the end of days, the seven heavens of the Archons will collapse on each other. The heaven of Yaldabaoth will split in two and cause the stars in his celestial sphere to fall.[108]

In the native Chinese Confucian traditions, heaven (Tian) is an important concept, where the ancestors reside and from which emperors drew their mandate to rule in their dynastic propaganda, for example.

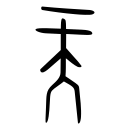

Heaven is a key concept in Chinese mythology, philosophies, and religions, and is on one end of the spectrum a synonym of Shangdi ("Supreme Deity") and on the other naturalistic end, a synonym for nature and the sky. The Chinese term for "heaven", Tian (天), derives from the name of the supreme deity of the Zhou dynasty. After their conquest of the Shang dynasty in 1122 BC, the Zhou people considered their supreme deity Tian to be identical with the Shang supreme deity Shangdi.[109] The Zhou people attributed Heaven with anthropomorphic attributes, evidenced in the etymology of the Chinese character for heaven or sky, which originally depicted a person with a large cranium. Heaven is said to see, hear and watch over all people. Heaven is affected by people's doings, and having personality, is happy and angry with them. Heaven blesses those who please it and sends calamities upon those who offend it.[110] Heaven was also believed to transcend all other spirits and gods, with Confucius asserting, "He who offends against Heaven has none to whom he can pray."[110]

Other philosophers born around the time of Confucius such as Mozi took an even more theistic view of heaven, believing that heaven is the divine ruler, just as the Son of Heaven (the King of Zhou) is the earthly ruler. Mozi believed that spirits and minor gods exist, but their function is merely to carry out the will of heaven, watching for evil-doers and punishing them. Thus they function as angels of heaven and do not detract from its monotheistic government of the world. With such a high monotheism, it is not surprising that Mohism championed a concept called "universal love" (jian'ai, 兼愛), which taught that heaven loves all people equally and that each person should similarly love all human beings without distinguishing between his own relatives and those of others.[111] In Mozi's Will of Heaven (天志), he writes:

"I know Heaven loves men dearly not without reason. Heaven ordered the sun, the moon, and the stars to enlighten and guide them. Heaven ordained the four seasons, Spring, Autumn, Winter, and Summer, to regulate them. Heaven sent down snow, frost, rain, and dew to grow the five grains and flax and silk that so the people could use and enjoy them. Heaven established the hills and rivers, ravines and valleys, and arranged many things to minister to man's good or bring him evil. He appointed the dukes and lords to reward the virtuous and punish the wicked, and to gather metal and wood, birds and beasts, and to engage in cultivating the five grains and flax and silk to provide for the people's food and clothing. This has been so from antiquity to the present."

Original Chinese: 「且吾所以知天之愛民之厚者有矣,曰以磨為日月星辰,以昭道之;制為四時春秋冬夏,以紀綱之;雷降雪霜雨露,以長遂五穀麻絲,使民得而財利之;列為山川谿谷,播賦百事,以臨司民之善否;為王公侯伯,使之賞賢而罰暴;賊金木鳥獸,從事乎五穀麻絲,以為民衣食之財。自古及今,未嘗不有此也。」

Mozi, Will of Heaven, Chapter 27, Paragraph 6, ca. 5th Century BC

Mozi criticized the Confucians of his own time for not following the teachings of Confucius. By the time of the later Han dynasty, however, under the influence of Xunzi, the Chinese concept of heaven and Confucianism itself had become mostly naturalistic, though some Confucians argued that Heaven was where ancestors reside. Worship of heaven in China continued with the erection of shrines, the last and greatest being the Temple of Heaven in Beijing, and the offering of prayers. The ruler of China in every Chinese dynasty would perform annual sacrificial rituals to heaven, usually by slaughtering two healthy bulls as a sacrifice.

_(2).jpg/440px-018_Devas_in_Heaven_(9174314518)_(2).jpg)

In Buddhism there are several heavens, all of which are still part of samsara (illusionary reality). Those who accumulate good karma may be reborn[112] in one of them. However, their stay in heaven is not eternal—eventually they will use up their good karma and will undergo rebirth into another realm, as a human, animal or other being. Because heaven is temporary and part of samsara, Buddhists focus more on escaping the cycle of rebirth and reaching enlightenment (nirvana). Nirvana is not a heaven but a mental state.

According to Buddhist cosmology the universe is impermanent and beings transmigrate through several existential "planes" in which this human world is only one "realm" or "path".[113] These are traditionally envisioned as a vertical continuum with the heavens existing above the human realm, and the realms of the animals, hungry ghosts and hell beings existing beneath it. According to Jan Chozen Bays in her book, Jizo: Guardian of Children, Travelers, and Other Voyagers, the realm of the asura is a later refinement of the heavenly realm and was inserted between the human realm and the heavens. One important Buddhist heaven is the Trāyastriṃśa, which resembles Olympus of Greek mythology.

In the Mahayana world view, there are also pure lands which lie outside this continuum and are created by the Buddhas upon attaining enlightenment. Rebirth in the pure land of Amitabha is seen as an assurance of Buddhahood, for once reborn there, beings do not fall back into cyclical existence unless they choose to do so to save other beings, the goal of Buddhism being the obtainment of enlightenment and freeing oneself and others from the birth-death cycle.

The Tibetan word Bardo means literally "intermediate state". In Sanskrit the concept has the name antarabhāva.

The lists below are ordered from highest to lowest of the heavenly worlds.

Here the denizens are Brahmās, and the ruler is Mahābrahmā. After developing the four Brahmavihāras, King Makhādeva rebirths here after death. The monk Tissa and Brāhmana Jānussoni were also reborn here.

The lifespan of a Brahmās is not stated but is not eternal.

Parinirmita-vaśavartin (Pali: Paranimmita-vasavatti)

The heaven of devas have "power over (others') creations". These devas do not create pleasing forms that they desire for themselves, but their desires are fulfilled by the acts of other devas who seek their favor. The ruler of this world is called Vaśavartin (Pāli: Vasavatti), who has longer life, greater beauty, more power and happiness and more delightful sense-objects than the other devas of his world. This world is also the home of the devaputra (being of a divine race) called Māra, who endeavors to keep all beings of the Kāmadhātu in the grip of sensual pleasures. Māra is also sometimes called Vaśavartin, but in general these two dwellers in this world are kept distinct. The beings of this world are 3 lǐ (1,400 m; 4,500 feet) tall and live for 9,216,000,000 years (Sarvāstivāda tradition).

Nirmāṇarati (Pali: Nimmānaratī)

The world of devas "delighting in their creations". The devas of this world are capable of making any appearance to please themselves. The lord of this world is called Sunirmita (Pāli Sunimmita); his wife is the rebirth of Visākhā, formerly the chief upāsikā (female lay devotee) of the Buddha. The beings of this world are 2+1⁄2 lǐ (1,140 m; 3,750 feet) tall and live for 2,304,000,000 years (Sarvāstivāda tradition).

Tuṣita (Pali: Tusita)

The world of the "joyful" devas, it is best known for being the world in which a Bodhisattva lives before being reborn in the world of humans. Until a few thousand years ago, the Bodhisattva of this world was Śvetaketu (Pāli: Setaketu), who was reborn as Siddhārtha, who would become the Buddha Śākyamuni; since then the Bodhisattva has been Nātha (or Nāthadeva) who will be reborn as Ajita and will become the Buddha Maitreya (Pāli Metteyya). While this Bodhisattva is the foremost of the dwellers in Tuṣita, the ruler of this world is another deva called Santuṣita (Pāli: Santusita). The beings of this world are 2 lǐ (910 m; 3,000 feet) tall and live for 576,000,000 years (Sarvāstivāda tradition). Anāthapindika, a Kosālan householder and benefactor to the Buddha's order was reborn here.

Yāma

The denizens here have a lifespan of 144,000,000 years.

Trāyastriṃśa (Pali: Tāvatimsa)

The ruler of this heaven is Indra or Shakra, and the realm is also called Trayatrimia. Each denizen addresses other denizens with the title "mārisa".

The governing hall of this heaven is called Sudhamma Hall. This heaven has a garden Nandanavana with damsels, as its most magnificent sight.

Ajita, the Licchavi army general, was reborn here. Gopika, the Sākyan girl, was reborn as a male god in this realm.

Any Buddhist reborn in this realm can outshine any of the previously dwelling denizens because of the extra merit acquired for following the Buddha's teachings. The denizens here have a lifespan of 36,000,000 years.

The heaven "of the Four Great Kings", its rulers are the four Great Kings of the name, Virūḍhaka विरुद्धक, Dhṛtarāṣṭra धृतराष्ट्र, Virūpākṣa विरुपाक्ष, and their leader Vaiśravaṇa वैश्यवर्ण. The devas who guide the Sun and Moon are also considered part of this world, as are the retinues of the four kings, composed of Kumbhāṇḍas कुम्भाण्ड (dwarfs), Gandharva गन्धर्वs (fairies), Nāgas नाग (snakes) and Yakṣas यक्ष (goblins). The beings of this world are 230 m (750 feet) tall and live for 9,000,000 years (Sarvāstivāda tradition) or 90,000 years (Vibhajyavāda tradition).

The Heaven of the Comfort from Others’ Transformations

The Heaven of Bliss by Transformation

The Tushita Heaven

The Suyama Heaven

The Trayastrimsha Heaven

The Heaven of the Four Kings

Ouyi Zhixu[114] explains that the Shurangama sutra only emphasizes avoidance of deviant sexual desire, but one would naturally need to abide by the 10 good conducts to be born in these heavens.

Tibetan literature classifies the heavenly worlds into 5 major types:

Attaining heaven is not the final pursuit in Hinduism as heaven itself is ephemeral and related to physical body. Only being tied by the bhoot-tattvas, heaven cannot be perfect either and is just another name for pleasurable and mundane material life. According to Hindu cosmology, above the earthly plane, are other planes: (1) Bhuva Loka, (2) Swarga Loka, meaning Good Kingdom, is the general name for heaven in Hinduism, a heavenly paradise of pleasure, where most of the Hindu Devatas (Deva) reside along with the king of Devas, Indra, and beatified mortals. Some other planes are Mahar Loka, Jana Loka, Tapa Loka and Satya Loka. Since heavenly abodes are also tied to the cycle of birth and death, any dweller of heaven or hell will again be recycled to a different plane and in a different form per the karma and "maya" i.e. the illusion of Samsara. This cycle is broken only by self-realization by the Jivatma. This self-realization is Moksha (Turiya, Kaivalya).

The concept of moksha is unique to Hinduism. Moksha stands for liberation from the cycle of birth and death and final communion with Brahman. With moksha, a liberated soul attains the stature and oneness with Brahman or Paramatma. Different schools such as Vedanta, Mimansa, Sankhya, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, and Yoga offer subtle differences in the concept of Brahman, obvious Universe, its genesis and regular destruction, Jivatma, Nature (Prakriti) and also the right way in attaining perfect bliss or moksha.

In the Vaishnava traditions the highest heaven is Vaikuntha, which exists above the six heavenly lokas and outside of the mahat-tattva or mundane world. It's where eternally liberated souls who have attained moksha reside in eternal sublime beauty with Lakshmi and Narayana (a manifestation of Vishnu).

In the Nasadiya Sukta, the heavens/sky Vyoman is mentioned as a place from which an overseeing entity surveys what has been created. However, the Nasadiya Sukta questions the omniscience of this overseer.

The shape of the Universe as described in Jainism is shown at right. Unlike the current convention of using North direction as the top of map, this uses South as the top. The shape is similar to a part of human form standing upright.

The Deva Loka (heavens) are at the symbolic "chest", where all souls enjoying the positive karmic effects reside. The heavenly beings are referred to as devas (masculine form) and devis (feminine form). According to Jainism, there is not one heavenly abode, but several layers to reward appropriately the souls of varying degree of karmic merits. Similarly, beneath the "waist" are the Narka Loka (hell). Human, animal, insect, plant and microscopic life forms reside on the middle.

The pure souls (who reached Siddha status) reside at the very south end (top) of the Universe. They are referred to in Tamil literature as தென்புலத்தார் (Kural 43).

Sikhs believe that heaven and hell are also both in this world where everyone reaps the fruit of karma.[115] They refer to good and evil stages of life respectively and can be lived now and here during our life on Earth.[116] Bhagat Kabir in the Guru Granth Sahib rejects the otherworldly heaven and says that one can experience heaven on this Earth through the company of holy people.

He claims to know the Lord, who is beyond measure and beyond thought; By mere words, he plans to enter heaven. I do not know where heaven is. Everyone claims that he plans to go there. By mere talk, the mind is not appeased. The mind is only appeased, when egotism is conquered. As long as the mind is filled with the desire for heaven, He does not dwell at the Lord's Feet. Says Kabeer, unto whom should I tell this? The Company of the Holy is heaven.

— Bhagat Kabir, Guru Granth Sahib 325 [117]

The Nahua people such as the Aztecs, Chichimecs and the Toltecs believed that the heavens were constructed and separated into 13 levels. Each level had from one to many Lords living in and ruling these heavens. Most important of these heavens was Omeyocan (Place of Two). The Thirteen Heavens were ruled by Ometeotl, the dual Lord, creator of the Dual-Genesis who, as male, takes the name Ometecuhtli (Two Lord), and as female is named Omecihuatl (Two Lady).

In the creation myths of Polynesian mythology are found various concepts of the heavens and the underworld. These differ from one island to another. What they share is the view of the universe as an egg or coconut that is divided between the world of humans (earth), the upper world of heavenly gods, and the underworld. Each of these is subdivided in a manner reminiscent of Dante's Divine Comedy, but the number of divisions and their names differs from one Polynesian culture to another.[118]

In Māori mythology, the heavens are divided into a number of realms. Different tribes number the heaven differently, with as few as two and as many as fourteen levels. One of the more common versions divides heaven thus:

The Māori believe these heavens are supported by pillars. Other Polynesian peoples see them being supported by gods (as in Hawaii). In one Tahitian legend, heaven is supported by an octopus.

The Polynesian conception of the universe and its division is nicely illustrated by a famous drawing made by a Tuomotuan chief in 1869. Here, the nine heavens are further divided into left and right, and each stage is associated with a stage in the evolution of the earth that is portrayed below. The lowest division represents a period when the heavens hung low over the earth, which was inhabited by animals that were not known to the islanders. In the third division is shown the first murder, the first burials, and the first canoes, built by Rata. In the fourth division, the first coconut tree and other significant plants are born.[119]

It is believed in Theosophy, founded mainly by Helena Blavatsky, that each religion (including Theosophy) has its own individual heaven in various regions of the upper astral plane that fits the description of that heaven that is given in each religion, to which a soul that has been good in their previous life on Earth will go. The area of the upper astral plane of Earth in the upper atmosphere where the various heavens are located is called Summerland (Theosophists believe hell is located in the lower astral plane of Earth which extends downward from the surface of the earth to its center). However, Theosophists believe that the soul is recalled back to Earth after an average of about 1400 years by the Lords of Karma to incarnate again. The final heaven that souls go to billions of years in the future after they finish their cycle of incarnations is called Devachan.[120]

Anarchist Emma Goldman expressed this view when she wrote, "Consciously or unconsciously, most theists see in gods and devils, heaven and hell, reward and punishment, a whip to lash the people into obedience, meekness and contentment."[121]

Some have argued that a belief in a reward after death is poor motivation for moral behavior while alive.[122][123] Sam Harris wrote, "It is rather more noble to help people purely out of concern for their suffering than it is to help them because you think the Creator of the Universe wants you to do it, or will reward you for doing it, or will punish you for not doing it. The problem with this linkage between religion and morality is that it gives people bad reasons to help other human beings when good reasons are available."[124]

Many neuroscientists and neurophilosophers, such as Daniel Dennett, believe that consciousness is dependent upon the functioning of the brain and death is a cessation of consciousness, which would rule out heaven. Scientific research has discovered that some areas of the brain, like the reticular activating system or the thalamus, appear to be necessary for consciousness, because dysfunction of or damage to these structures causes a loss of consciousness.[125]

In Inside the Neolithic Mind (2005), Lewis-Williams and Pearce argue that many cultures around the world and through history neurally perceive a tiered structure of heaven, along with similarly structured circles of hell. The reports match so similarly across time and space that Lewis-Williams and Pearce argue for a neuroscientific explanation, accepting the percepts as real neural activations and subjective percepts during particular altered states of consciousness.

Many people who come close to death and have near-death experiences report meeting relatives or entering "the Light" in an otherworldly dimension, which shares similarities with the religious concept of heaven. Even though there are also reports of distressing experiences and negative life-reviews, which share some similarities with the concept of hell, the positive experience of meeting or entering "the Light" is reported as an immensely intense feeling of a state of love, peace and joy beyond human comprehension. Together with this intensely positive-feeling state, people who have near-death experiences also report that consciousness or a heightened state of awareness seems as if it is at the heart of experiencing a taste of "heaven".[126]

Works of fiction have included numerous conceptions of Heaven and Hell. The two most famous descriptions of Heaven are given in Dante Alighieri's Paradiso (of the Divine Comedy) and John Milton's Paradise Lost.

More recently scholars have questioned a Persian derivation for the Jewish doctrine because of certain problems of dating. Some experts have undercut the entire thesis by pointing out that we actually do not have any Zoroastrian texts that support the idea of resurrection prior to its appearance in early Jewish writings. It is not clear who influenced whom. Even more significant, the timing does not make sense: Judah emerged from Persian rule in the fourth century BCE, when Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) swept through the eastern Mediterranean and defeated the Persian Empire. But the idea of bodily resurrection does not appear in Jewish texts for well over a century after that.