Мохандас Карамчанд Ганди ( ИСО : Mōhanadāsa Karamacaṁda Gāṁdhī ; [c] 2 октября 1869 – 30 января 1948) был индийским юристом, антиколониальным националистом и политическим этиком , который использовал ненасильственное сопротивление , чтобы возглавить успешную кампанию за независимость Индии от британского правления . Он вдохновил движения за гражданские права и свободу по всему миру. Почетное обращение Махатма (от санскрита «великодушный, почтенный»), впервые примененное к нему в Южной Африке в 1914 году, теперь используется во всем мире. [2]

Родившийся и выросший в индуистской семье в прибрежном Гуджарате , Ганди обучался юриспруденции в Inner Temple в Лондоне и был принят в коллегию адвокатов в июне 1891 года в возрасте 22 лет. После двух неопределенных лет в Индии, где он не смог начать успешную юридическую практику, Ганди переехал в Южную Африку в 1893 году, чтобы представлять индийского торговца в судебном процессе. Он прожил в Южной Африке 21 год. Там Ганди создал семью и впервые применил ненасильственное сопротивление в кампании за гражданские права. В 1915 году, в возрасте 45 лет, он вернулся в Индию и вскоре приступил к организации крестьян, фермеров и городских рабочих для протеста против дискриминации и чрезмерного налога на землю.

Взяв на себя руководство Индийским национальным конгрессом в 1921 году, Ганди возглавил общенациональные кампании за сокращение бедности, расширение прав женщин, построение религиозной и этнической дружбы, прекращение неприкасаемости и, прежде всего, достижение свараджа или самоуправления. Ганди принял короткое дхоти, сотканное из пряжи ручной работы, как знак идентификации с сельской беднотой Индии. Он начал жить в самодостаточном жилом сообществе , питаться простой пищей и проводить длительные посты как средство как самоанализа, так и политического протеста. Принося антиколониальный национализм простым индийцам, Ганди повел их на борьбу с введенным британцами налогом на соль с помощью 400-километрового (250-мильного) соляного марша Данди в 1930 году и призывая британцев покинуть Индию в 1942 году. Он был заключен в тюрьму много раз и на многие годы как в Южной Африке, так и в Индии.

Видение Ганди независимой Индии, основанной на религиозном плюрализме, было оспорено в начале 1940-х годов мусульманским национализмом , который требовал отдельного отечества для мусульман в пределах Британской Индии . В августе 1947 года Великобритания предоставила независимость, но Британская Индийская империя была разделена на два доминиона , Индию с индуистским большинством и Пакистан с мусульманским большинством . Когда многие перемещенные индуисты, мусульмане и сикхи направлялись на свои новые земли, вспыхнуло религиозное насилие, особенно в Пенджабе и Бенгалии . Воздерживаясь от официального празднования независимости , Ганди посетил пострадавшие районы, пытаясь облегчить страдания. В последующие месяцы он провел несколько голодовок , чтобы остановить религиозное насилие. Последняя из них была начата в Дели 12 января 1948 года, когда Ганди было 78 лет. Убеждение, что Ганди был слишком решителен в своей защите как Пакистана, так и индийских мусульман, распространилось среди некоторых индуистов в Индии. Среди них был Натхурам Годсе , воинствующий индуистский националист из Пуны , Западная Индия, который убил Ганди , выпустив три пули в грудь на межконфессиональном молитвенном собрании в Дели 30 января 1948 года.

День рождения Ганди, 2 октября, отмечается в Индии как Ганди Джаянти , национальный праздник , а во всем мире как Международный день ненасилия . Ганди считается Отцом нации в постколониальной Индии. Во время националистического движения в Индии и в течение нескольких десятилетий сразу после него его также обычно называли Бапу ( гуджаратское ласковое слово для «отца», примерно «папа», [3] «папочка» [4] ).

Отец Ганди, Карамчанд Уттамчанд Ганди (1822–1885), служил деваном ( главным министром) штата Порбандар. [5] [6] Его семья происходила из тогдашней деревни Кутиана в тогдашнем штате Джунагадх . [7] Хотя Карамчанд был всего лишь клерком в администрации штата и имел начальное образование, он оказался способным главным министром. [7]

За время своего правления Карамчанд женился четыре раза. Его первые две жены умерли молодыми, после того как каждая родила дочь, а его третий брак оказался бездетным. В 1857 году Карамчанд попросил разрешения своей третьей жены снова жениться; в том же году он женился на Путлибай (1844–1891), которая также была родом из Джунагадха [7] и была из семьи пранами- вайшнавов . [8] [9] [10] У Карамчанда и Путлибай было четверо детей: сын Лакшмидас ( ок. 1860 –1914); дочь Ралиатбен (1862–1960); второй сын Карсандас ( ок. 1866 –1913). [11] [12] и третий сын, Мохандас Карамчанд Ганди [13] , который родился 2 октября 1869 года в Порбандаре (также известном как Судамапури ), прибрежном городе на полуострове Катхиавар , а затем входящем в состав небольшого княжества Порбандар в агентстве Катхиавар британского владычества . [ 14]

В 1874 году отец Ганди, Карамчанд, покинул Порбандар и переехал в меньший штат Раджкот , где стал советником его правителя, Такура Сахиба; хотя Раджкот был менее престижным штатом, чем Порбандар, британское региональное политическое агентство располагалось там, что давало дивану штата определенную безопасность. [15] В 1876 году Карамчанд стал диваном Раджкота, а его преемником на посту дивана Порбандара стал его брат Тулсидас. Затем семья Карамчанда воссоединилась с ним в Раджкоте. [15] В 1881 году они переехали в свой семейный дом Каба Ганди Но Дело. [16]

В детстве Ганди описывался своей сестрой Ралиат как «беспокойный, как ртуть, играющий или бродящий. Одним из его любимых занятий было выкручивание ушей собакам». [17] Индийская классика, особенно истории о Шраване и царе Харишчандре , оказали большое влияние на Ганди в детстве. В своей автобиографии Ганди утверждает, что они оставили неизгладимое впечатление в его сознании. Ганди пишет: «Это преследовало меня, и я, должно быть, бесчисленное количество раз изображал Харишчандру для себя». Ранняя самоидентификация Ганди с истиной и любовью как высшими ценностями прослеживается в этих эпических персонажах. [18] [19]

Религиозное происхождение семьи было эклектичным. Мохандас родился в гуджаратской индуистской семье Модх Баниа . [20] [21] Отец Ганди, Карамчанд, был индуистом, а его мать Путлибай была из семьи индуистов Пранами Вайшнава . [22] [23] Отец Ганди был из касты Модх Баниа в варне Вайшья . [24] Его мать происходила из средневековой традиции Пранами , основанной на кришна -бхакти , чьи религиозные тексты включают Бхагавад-гиту , Бхагавата-пурану и сборник из 14 текстов с учениями, которые, как полагает традиция, включают в себя суть Вед , Корана и Библии . [23] [25] На Ганди глубокое влияние оказала его мать, чрезвычайно набожная женщина, которая «не могла и подумать о приеме пищи без ежедневных молитв... она принимала самые суровые обеты и соблюдала их не дрогнув. Для нее было пустяком держать два или три последовательных поста». [26]

В возрасте девяти лет Ганди поступил в местную школу в Раджкоте , недалеко от своего дома. Там он изучал основы арифметики, историю, язык гуджарати и географию. [15] В возрасте 11 лет Ганди поступил в среднюю школу в Раджкоте, среднюю школу Альфреда . [28] Он был средним учеником, выигрывал некоторые призы, но был застенчивым и косноязычным учеником, не интересовавшимся играми; единственными товарищами Ганди были книги и школьные уроки. [29]

В мае 1883 года 13-летний Мохандас Ганди женился на 14-летней Кастурбай Гокулдас Кападия (ее первое имя обычно сокращалось до «Кастурба», а ласково до «Ба») в браке по договоренности , согласно обычаям региона того времени. [30] В процессе он потерял год в школе, но позже ему разрешили наверстать упущенное, ускорив учебу. [31] Свадьба Ганди была совместным мероприятием, на котором также поженились его брат и кузен. Вспоминая день их свадьбы, Ганди однажды сказал: «Поскольку мы мало что знали о браке, для нас это означало только носить новую одежду, есть сладости и играть с родственниками». Согласно преобладающей традиции, невеста-подросток должна была проводить много времени в доме своих родителей и вдали от мужа. [32]

Спустя много лет Мохандас с сожалением описывал похотливые чувства, которые он испытывал к своей молодой невесте, говоря: «Даже в школе я думал о ней, и мысль о наступлении ночи и нашей последующей встрече всегда преследовала меня». Позже Ганди вспоминал, что чувствовал ревность и собственнические чувства к ней, например, когда Кастурба посещала храм со своими подругами, и был сексуально похотлив в своих чувствах к ней. [33]

В конце 1885 года умер отец Ганди, Карамчанд. [34] Ганди покинул постель отца, чтобы побыть с женой всего за несколько минут до его смерти. Много десятилетий спустя Ганди писал: «Если бы животная страсть не ослепила меня, я был бы избавлен от пыток разлуки с отцом в его последние минуты». [35] Позже у Ганди, которому тогда было 16 лет, и его жены, которой было 17 лет, родился первый ребенок, который прожил всего несколько дней. Эти две смерти мучили Ганди. [34] У пары Ганди было еще четверо детей, все сыновья: Харилал , родившийся в 1888 году; Манилал , родившийся в 1892 году; Рамдас , родившийся в 1897 году; и Девдас , родившийся в 1900 году. [30]

В ноябре 1887 года 18-летний Ганди окончил среднюю школу в Ахмадабаде . [36] В январе 1888 года он поступил в колледж Самалдас в штате Бхавнагар , который тогда был единственным выдающим диплом высшим учебным заведением в регионе. Однако Ганди бросил учебу и вернулся к своей семье в Порбандар. [37]

Ганди бросил самый дешевый колледж, который он мог себе позволить в Бомбее. [38] Мавджи Дэйв Джошиджи, священник- брамин и друг семьи, посоветовал Ганди и его семье рассмотреть возможность изучения права в Лондоне. [37] [39] В июле 1888 года жена Ганди Кастурба родила их первого выжившего ребенка, Харилала. [40] Мать Ганди не была уверена в том, что Ганди оставил жену и семью и уехал так далеко от дома. Дядя Ганди Тулсидас также пытался отговорить своего племянника, но Ганди хотел уехать. Чтобы убедить жену и мать, Ганди дал обет перед матерью, что он будет воздерживаться от мяса, алкоголя и женщин. Брат Ганди, Лакшмидас, который уже был юристом, приветствовал план Ганди по обучению в Лондоне и предложил поддержать его. Путлибай дала Ганди свое разрешение и благословение. [37] [41]

10 августа 1888 года Ганди, в возрасте 18 лет, покинул Порбандар и отправился в Мумбаи, тогда известный как Бомбей. Местная газета, освещавшая прощальную церемонию в его старой средней школе в Раджкоте, отметила, что Ганди был первым баниа из Катхиавара, который отправился в Англию для сдачи экзамена на адвоката. [42] По прибытии в Лондон он остановился в местной общине Модх Баниа, старейшины которой предупредили Ганди, что Англия соблазнит его пойти на компромисс со своей религией и есть и пить по-западному. Несмотря на то, что Ганди сообщил им о своем обещании матери и ее благословении, Ганди был отлучен от своей касты. Ганди проигнорировал это и 4 сентября отплыл из Бомбея в Лондон, а его брат проводил его. [38] [40] Ганди посещал Университетский колледж в Лондоне , где он брал уроки английской литературы у Генри Морли в 1888–1889 годах. [43]

Ганди также поступил в юридическую школу Inns of Court в Иннер-Темпле с намерением стать адвокатом . [39] Его детская застенчивость и замкнутость сохранились и в подростковом возрасте. Ганди сохранил эти черты, когда приехал в Лондон, но присоединился к группе практики публичных выступлений и преодолел свою застенчивость в достаточной степени, чтобы заниматься юридической практикой. [44]

Ганди проявлял живой интерес к благосостоянию обедневших доковых общин Лондона. В 1889 году в Лондоне разразился ожесточенный трудовой спор , в ходе которого докеры бастовали, требуя лучшей оплаты и условий труда, а моряки, судостроители, работницы фабрик и другие присоединились к забастовке в знак солидарности. Бастующие добились успеха, отчасти благодаря посредничеству кардинала Мэннинга , что побудило Ганди и его индийского друга посетить кардинала и поблагодарить его за работу. [45]

Его клятва матери повлияла на время, проведенное Ганди в Лондоне. Ганди пытался перенять «английские» обычаи, включая уроки танцев. [46] Однако он не оценил пресную вегетарианскую еду, предлагаемую его домовладелицей, и часто был голоден, пока не нашел один из немногих вегетарианских ресторанов Лондона. Под влиянием произведений Генри Солта Ганди вступил в Лондонское вегетарианское общество и был избран в его исполнительный комитет под эгидой его президента и благотворителя Арнольда Хиллса . [47] Достижением во время работы в комитете стало создание отделения в Бейсуотере . [48] Некоторые из вегетарианцев, с которыми встречался Ганди, были членами Теософского общества , которое было основано в 1875 году для дальнейшего всеобщего братства и которое было посвящено изучению буддийской и индуистской литературы. Они призвали Ганди присоединиться к ним в чтении Бхагавад-гиты как в переводе, так и в оригинале. [47]

У Ганди были дружеские и продуктивные отношения с Хиллзом, но эти двое мужчин придерживались разных взглядов на продолжение членства в LVS своего коллеги по комитету Томаса Аллинсона . Их разногласия являются первым известным примером того, как Ганди бросает вызов власти, несмотря на свою застенчивость и темпераментную нерасположенность к конфронтации. [ необходима цитата ]

Аллинсон продвигал новые доступные методы контроля рождаемости , но Хиллс не одобрял их, полагая, что они подрывают общественную мораль. Он считал вегетарианство моральным движением и что Аллинсону поэтому больше не следует оставаться членом LVS. Ганди разделял взгляды Хиллса на опасности контроля рождаемости, но защищал право Аллинсона отличаться. [49] Ганди было бы трудно бросить вызов Хиллсу; Хиллс был на 12 лет старше его и, в отличие от Ганди, очень красноречив. Хиллс финансировал LVS и был капитаном промышленности со своей компанией Thames Ironworks, нанимавшей более 6000 человек в Ист-Энде Лондона . Хиллс также был очень успешным спортсменом, который позже основал футбольный клуб West Ham United . В своей книге 1927 года «Автобиография, т. I» Ганди писал:

Вопрос глубоко интересовал меня... Я высоко ценил мистера Хиллса и его щедрость. Но я считал совершенно неуместным исключать человека из вегетарианского общества только потому, что он отказывался считать пуританскую мораль одним из объектов общества [49]

Было выдвинуто предложение об отстранении Аллинсона, которое было обсуждено и поставлено на голосование комитетом. Застенчивость Ганди помешала ему защитить Аллинсона на заседании комитета. Ганди записал свои взгляды на бумаге, но застенчивость помешала Ганди зачитать свои аргументы, поэтому Хиллс, президент, попросил другого члена комитета зачитать их для него. Хотя некоторые другие члены комитета согласились с Ганди, голосование было проиграно, и Аллинсон был исключен. Не было никаких обид, и Хиллс предложил тост на прощальном ужине LVS в честь возвращения Ганди в Индию. [50]

Ганди, в возрасте 22 лет, был призван в адвокатуру в июне 1891 года, а затем уехал из Лондона в Индию, где узнал, что его мать умерла, пока он был в Лондоне, и что его семья скрыла эту новость от Ганди. [47] Его попытки основать юридическую практику в Бомбее потерпели неудачу, потому что Ганди был психологически неспособен допрашивать свидетелей. Он вернулся в Раджкот, чтобы скромно зарабатывать на жизнь составлением петиций для тяжущихся сторон, но Ганди был вынужден остановиться после столкновения с британским офицером Сэмом Санни. [47] [48]

В 1893 году мусульманский торговец в Катхиаваре по имени Дада Абдулла связался с Ганди. Абдулла владел крупным успешным судоходным бизнесом в Южной Африке. Его дальний родственник в Йоханнесбурге нуждался в адвокате, и они предпочли кого-то с происхождением катхиавари. Ганди поинтересовался его оплатой за работу. Они предложили общую зарплату в размере 105 фунтов стерлингов (~4143 доллара в деньгах 2023 года) плюс дорожные расходы. Он согласился, зная, что это будет как минимум годовое обязательство в колонии Натал , Южная Африка, также являющейся частью Британской империи. [48] [51]

В апреле 1893 года Ганди, в возрасте 23 лет, отправился в Южную Африку, чтобы стать адвокатом двоюродного брата Абдуллы. [51] [52] Ганди провел 21 год в Южной Африке, где он развивал свои политические взгляды, этику и политику. [53] [54] В это время Ганди ненадолго вернулся в Индию в 1902 году, чтобы мобилизовать поддержку для благосостояния индийцев в Южной Африке. [55]

Сразу по прибытии в Южную Африку Ганди столкнулся с дискриминацией из-за цвета кожи и происхождения. [56] Ганди не разрешили сидеть с европейскими пассажирами в дилижансе и приказали сесть на пол рядом с водителем, а затем избили, когда он отказался; в другом месте Ганди пинками сбросили в канаву за то, что он осмелился пройти рядом с домом, в другом случае его сбросили с поезда в Питермарицбурге после того, как он отказался выйти из первого класса. [38] [57] Ганди сидел на вокзале, дрожа всю ночь и размышляя, следует ли ему вернуться в Индию или протестовать за свои права. [57] Ганди решил протестовать, и на следующий день ему разрешили сесть в поезд. [58] В другом случае магистрат суда Дурбана приказал Ганди снять тюрбан, что он отказался сделать. [38] Индийцам не разрешалось ходить по общественным пешеходным дорожкам в Южной Африке. Ганди был выброшен полицейским с пешеходной дорожки на улицу без предупреждения. [38]

Когда Ганди прибыл в Южную Африку, по словам Артура Германа, он считал себя «в первую очередь британцем, а во вторую — индийцем». [59] Однако предубеждение против Ганди и его соотечественников-индийцев со стороны британцев, которое Ганди испытал и наблюдал, глубоко беспокоило его. Ганди находил это унизительным, пытаясь понять, как некоторые люди могут чувствовать честь, превосходство или удовольствие от таких бесчеловечных практик. [57] Ганди начал сомневаться в положении своего народа в Британской империи . [60]

Дело Абдуллы, которое привело его в Южную Африку, завершилось в мае 1894 года, и индийская община организовала прощальную вечеринку для Ганди, когда он готовился вернуться в Индию. [61] Однако новое дискриминационное предложение правительства Натала привело к тому, что Ганди продлил свой первоначальный срок пребывания в Южной Африке. Ганди планировал помочь индийцам выступить против законопроекта, лишавшего их права голоса , права, которое тогда предлагалось сделать исключительным европейским правом. Он попросил Джозефа Чемберлена , британского министра по делам колоний, пересмотреть свою позицию по этому законопроекту. [53] Хотя Ганди не смог остановить принятие законопроекта, его кампания была успешной в привлечении внимания к недовольству индийцев в Южной Африке. Он помог основать Индийский конгресс Натала в 1894 году, [48] [58] и через эту организацию Ганди превратил индийскую общину Южной Африки в единую политическую силу. В январе 1897 года, когда Ганди высадился в Дурбане, на него напала толпа белых поселенцев, [62] и Ганди удалось спастись только благодаря усилиям жены полицейского суперинтенданта. [ необходима цитата ] Однако Ганди отказался выдвигать обвинения против любого члена толпы. [48]

Во время англо-бурской войны Ганди добровольно вызвался в 1900 году сформировать группу носильщиков в качестве Корпуса скорой помощи Индии Натала . По словам Артура Германа, Ганди хотел опровергнуть стереотип британских колонистов о том, что индусы не подходят для «мужественных» действий, связанных с опасностью и напряжением, в отличие от мусульманских « воинственных рас ». [63] Ганди собрал 1100 индийских добровольцев для поддержки британских боевых войск против буров. Они были обучены и получили медицинскую сертификацию для службы на передовой. Они были вспомогательными в битве при Коленсо для Белого добровольческого корпуса скорой помощи. В битве при Спион-Копе Ганди и его носильщики двинулись на передовую и должны были нести раненых солдат на протяжении многих миль в полевой госпиталь, поскольку местность была слишком неровной для машин скорой помощи. Ганди и 37 других индийцев получили медаль Южной Африки от королевы . [64] [65]

В 1906 году правительство Трансвааля обнародовало новый Закон, обязывающий регистрировать индийское и китайское население колонии. На массовом митинге протеста, состоявшемся в Йоханнесбурге 11 сентября того же года, Ганди впервые принял свою все еще развивающуюся методологию Сатьяграхи (преданности истине), или ненасильственного протеста. [66] По словам Энтони Парела, Ганди также находился под влиянием тамильского морального текста Тируккурах после того, как Лев Толстой упомянул его в их переписке, которая началась с « Письма к индусу ». [67] [68] Ганди призывал индийцев бросить вызов новому закону и понести наказание за это. Возникли его идеи протестов, навыков убеждения и связей с общественностью. Ганди привез их обратно в Индию в 1915 году. [69] [70]

Ганди сосредоточил свое внимание на индийцах и африканцах, когда он был в Южной Африке. Изначально Ганди не интересовался политикой, но это изменилось после того, как он подвергся дискриминации и издевательствам, например, когда его вышвырнул из вагона поезда из-за цвета кожи белый служащий поезда. После нескольких подобных инцидентов с белыми в Южной Африке мышление и фокус Ганди изменились, и он почувствовал, что должен противостоять этому и бороться за права. Ганди вошел в политику, сформировав Натальский индийский конгресс. [71] По словам Эшвина Десаи и Гулама Вахеда, взгляды Ганди на расизм в некоторых случаях спорны. Он подвергался преследованиям с самого начала в Южной Африке. Как и в случае с другими цветными людьми, белые чиновники отказывали Ганди в его правах, а пресса и люди на улицах издевались и называли Ганди «паразитом», «полуварваром», «язвой», «убогим кули», «желтым человеком» и другими эпитетами. Люди даже плевали на него, выражая расовую ненависть. [72]

Находясь в Южной Африке, Ганди сосредоточился на расовом преследовании индийцев, прежде чем он начал сосредотачиваться на расизме в отношении африканцев. В некоторых случаях, как утверждают Десаи и Вахед, поведение Ганди было одним из проявлений добровольного участия в расовых стереотипах и эксплуатации африканцев. [72] Во время речи в сентябре 1896 года Ганди жаловался, что белые в британской колонии Южная Африка «унижают индийцев до уровня неотесанных кафров ». [73] Ученые приводят это как пример доказательства того, что Ганди в то время думал об индийцах и чернокожих южноафриканцах по-разному. [72] В качестве другого примера, приведенного Германом, Ганди в возрасте 24 лет подготовил юридическую записку для Натальской ассамблеи в 1895 году, добиваясь права голоса для индийцев. Ганди ссылался на историю рас и мнения европейских востоковедов о том, что «англосаксы и индийцы произошли от одного и того же арийского племени или, скорее, индоевропейских народов», и утверждал, что индийцев не следует объединять с африканцами. [61]

Годы спустя Ганди и его коллеги служили и помогали африканцам в качестве медсестер и выступая против расизма. Лауреат Нобелевской премии мира Нельсон Мандела входит в число поклонников усилий Ганди по борьбе с расизмом в Африке. [74] Общий образ Ганди, утверждают Десаи и Вахед, был переосмыслен после его убийства, как будто Ганди всегда был святым, тогда как на самом деле его жизнь была более сложной, содержала неудобные истины и менялась со временем. [72] Ученые также указали на доказательства богатой истории сотрудничества и усилий Ганди и индийского народа с небелыми южноафриканцами против преследования африканцев и апартеида . [75]

В 1906 году, когда в колонии Наталь вспыхнуло восстание Бамбата , тогдашний 36-летний Ганди, несмотря на симпатии к зулусским повстанцам, призвал индийских южноафриканцев сформировать добровольческий отряд носильщиков. [76] В своей статье в Indian Opinion Ганди утверждал, что военная служба будет полезна индийской общине, и утверждал, что она принесет им «здоровье и счастье». [77] В конечном итоге Ганди возглавил добровольческий смешанный отряд индийских и африканских носильщиков для лечения раненых бойцов во время подавления восстания. [76]

Медицинское подразделение под командованием Ганди проработало менее двух месяцев, прежде чем было расформировано. [76] После подавления восстания колониальное руководство не проявило никакого интереса к распространению на индийскую общину гражданских прав, предоставленных белым южноафриканцам . Это привело к разочарованию Ганди в Империи и вызвало в нем духовное пробуждение; историк Артур Л. Герман писал, что африканский опыт Ганди был частью его великого разочарования в Западе, превратив Ганди в «бескомпромиссного несотрудничающего». [77]

К 1910 году газета Ганди, Indian Opinion , освещала сообщения о дискриминации африканцев со стороны колониального режима. Ганди заметил, что африканцы «единственные являются коренными жителями земли. … Белые, с другой стороны, заняли землю силой и присвоили ее себе». [78]

В 1910 году Ганди основал с помощью своего друга Германа Калленбаха идеалистическую общину, которую они назвали «Ферма Толстого» недалеко от Йоханнесбурга. [79] [80] Там Ганди вынашивал свою политику мирного сопротивления. [81]

В годы после того, как чернокожие южноафриканцы получили право голоса в Южной Африке (1994), Ганди был провозглашен национальным героем и ему было воздвигнуто множество памятников. [82]

По просьбе Гопала Кришны Гокхале , переданной Ганди через К. Ф. Эндрюса , Ганди вернулся в Индию в 1915 году. Он принес международную известность как ведущий индийский националист, теоретик и общественный организатор.

Ганди присоединился к Индийскому национальному конгрессу и был представлен индийским проблемам, политике и индийскому народу, в первую очередь, Гокхале. Гокхале был ключевым лидером партии Конгресса, наиболее известным своей сдержанностью и умеренностью, а также своим упорством в работе внутри системы. Ганди взял либеральный подход Гокхале, основанный на британских традициях вигов , и преобразовал его, чтобы он выглядел индийским. [83]

Ганди взял на себя руководство Конгрессом в 1920 году и начал наращивать требования, пока 26 января 1930 года Индийский национальный конгресс не объявил независимость Индии. Британцы не признали декларацию, но последовали переговоры, в ходе которых Конгресс принял участие в управлении провинцией в конце 1930-х годов. Ганди и Конгресс отказались от поддержки Раджа, когда вице-король объявил войну Германии в сентябре 1939 года без консультаций. Напряженность нарастала до тех пор, пока Ганди не потребовал немедленной независимости в 1942 году, и британцы ответили заключением в тюрьму его и десятков тысяч лидеров Конгресса. Тем временем Мусульманская лига сотрудничала с Великобританией и, вопреки сильному сопротивлению Ганди, выступила с требованиями о полностью отдельном мусульманском государстве Пакистан. В августе 1947 года британцы разделили землю с Индией и Пакистаном, каждая из которых добилась независимости на условиях, которые Ганди не одобрял. [84]

В апреле 1918 года, во время последней части Первой мировой войны , вице-король пригласил Ганди на Военную конференцию в Дели. [85] Ганди согласился поддержать военные усилия. [38] [86] В отличие от войны с зулусами 1906 года и начала Первой мировой войны в 1914 году, когда он набирал добровольцев для Корпуса скорой помощи, на этот раз Ганди попытался набрать бойцов. В листовке от июня 1918 года под названием «Призыв к зачислению» Ганди писал: «Чтобы добиться такого положения вещей, мы должны иметь возможность защищать себя, то есть способность носить оружие и использовать его... Если мы хотим научиться использовать оружие с максимально возможной быстротой, наш долг записаться в армию». [87] Однако Ганди оговорил в письме личному секретарю вице-короля , что он «лично не убьет и не ранит никого, ни друга, ни врага». [88]

Поддержка Ганди военной кампании поставила под сомнение его последовательность в ненасилии. Личный секретарь Ганди отметил, что «вопрос о последовательности между его кредо « Ахимса » (ненасилие) и его вербовочной кампанией был поднят не только тогда, но и обсуждается с тех пор». [86] По словам политического и педагогического ученого Кристиана Бартольфа, поддержка Ганди войны проистекала из его убеждения в том, что истинная ахимса не может существовать одновременно с трусостью. Поэтому Ганди считал, что индийцы должны быть готовы и способны использовать оружие, прежде чем они добровольно выберут ненасилие. [89]

В июле 1918 года Ганди признал, что не смог убедить ни одного человека записаться на мировую войну. «До сих пор у меня нет ни одного рекрута, кроме меня», — писал Ганди. Он добавил: «Они возражают, потому что боятся умереть». [90]

Первое крупное достижение Ганди произошло в 1917 году с агитацией Чампарана в Бихаре . Агитация Чампарана натравила местное крестьянство на в основном англо-индийских владельцев плантаций, которых поддерживала местная администрация. Крестьяне были вынуждены выращивать индиго ( Indigofera sp.), товарную культуру для красителя индиго , спрос на который снижался в течение двух десятилетий, и были вынуждены продавать свой урожай плантаторам по фиксированной цене. Недовольные этим, крестьяне обратились к Ганди в его ашрам в Ахмадабаде. Следуя стратегии ненасильственного протеста, Ганди застал администрацию врасплох и добился уступок от властей. [91]

В 1918 году Кхеда пострадала от наводнений и голода, и крестьянство требовало освобождения от налогов. Ганди перенес свою штаб-квартиру в Надиад , [92] организовав множество сторонников и новых добровольцев из региона, самым известным из которых был Валлабхай Патель . [93] Используя несотрудничество как метод, Ганди инициировал кампанию по сбору подписей, в ходе которой крестьяне обещали не платить доход даже под угрозой конфискации земли. Социальный бойкот мамлатдаров и талатдаров (должностных лиц по доходам в округе) сопровождал агитацию. Ганди упорно трудился, чтобы завоевать общественную поддержку агитации по всей стране. В течение пяти месяцев администрация отказывалась, но к концу мая 1918 года правительство уступило по важным положениям и смягчило условия уплаты налога с доходов до тех пор, пока не закончился голод. В Кхеде Валлабхай Патель представлял фермеров на переговорах с британцами, которые приостановили сбор доходов и освободили всех заключенных. [94]

В 1919 году, после Первой мировой войны, Ганди (в возрасте 49 лет) искал политического сотрудничества с мусульманами в своей борьбе против британского империализма, поддерживая Османскую империю , которая потерпела поражение в мировой войне. До этой инициативы Ганди в Британской Индии были обычным явлением общинные споры и религиозные беспорядки между индуистами и мусульманами, такие как беспорядки 1917–1918 годов. Ганди уже открыто поддерживал британскую корону в Первой мировой войне. [95] Это решение Ганди было отчасти мотивировано британским обещанием ответить взаимностью на помощь свараджем ( самоуправлением) индийцам после окончания Первой мировой войны. [96] Британское правительство предложило вместо самоуправления незначительные реформы, разочаровав Ганди. [97] Он объявил о своих намерениях сатьяграхи (гражданского неповиновения). Британские колониальные чиновники сделали свой ответный шаг, приняв Закон Роулатта , чтобы заблокировать движение Ганди. Закон позволил британскому правительству рассматривать участников гражданского неповиновения как преступников и дал ему правовое основание арестовывать любого человека для «превентивного бессрочного заключения под стражу, лишения свободы без судебного надзора или необходимости судебного разбирательства». [98]

Ганди считал, что индуистско-мусульманское сотрудничество необходимо для политического прогресса против британцев. Он использовал движение Халифат , в котором мусульмане -сунниты в Индии, их лидеры, такие как султаны княжеств в Индии и братья Али, отстаивали турецкого халифа как символ солидарности суннитской исламской общины ( уммы ). Они видели в халифе свое средство поддержки ислама и исламского права после поражения Османской империи в Первой мировой войне. [99] [100] [101] Поддержка Ганди движения Халифат привела к неоднозначным результатам. Первоначально она привела к сильной поддержке Ганди мусульманами. Однако лидеры индуистов, включая Рабиндраната Тагора, подвергли сомнению лидерство Ганди, поскольку они были в основном против признания или поддержки суннитского исламского халифа в Турции. [d]

Растущая поддержка мусульман Ганди после того, как он отстаивал дело халифа, временно остановила индуистско-мусульманское насилие в общинах. Это предоставило доказательства межобщинной гармонии в совместных демонстрационных митингах сатьяграхи Роулэтта , повысив статус Ганди как политического лидера для британцев. [105] [106] Его поддержка движения Халифат также помогла Ганди оттеснить Мухаммеда Али Джинну , который объявил о своем несогласии с подходом Ганди к движению несотрудничества сатьяграхи . Джинна начал создавать свою независимую поддержку, а позже возглавил требование Западного и Восточного Пакистана. Хотя они согласились в общих чертах о независимости Индии, они не согласились о средствах ее достижения. Джинна был в основном заинтересован в общении с британцами посредством конституционных переговоров, а не в попытках агитировать массы. [107] [108] [109]

В 1922 году движение Халифат постепенно распалось после окончания движения несотрудничества с арестом Ганди. [110] Ряд мусульманских лидеров и делегатов покинули Ганди и Конгресс. [111] Снова вспыхнули индуистско-мусульманские общинные конфликты, и во многих городах снова вспыхнули смертоносные религиозные беспорядки, 91 из которых произошло только в Объединенных провинциях Агра и Ауд . [112] [113]

В своей книге Hind Swaraj (1909) 40-летний Ганди заявил, что британское правление было установлено в Индии при сотрудничестве индийцев и сохранилось только благодаря этому сотрудничеству. Если индийцы откажутся сотрудничать, британское правление рухнет и наступит сварадж (независимость Индии). [6] [114]

В феврале 1919 года Ганди предупредил вице-короля Индии телеграммой, что если британцы примут закон Роулатта , он призовет индийцев начать гражданское неповиновение. [115] Британское правительство проигнорировало его и приняло закон, заявив, что не поддастся угрозам. Последовало гражданское неповиновение сатьяграха , когда люди собрались, чтобы выразить протест против закона Роулатта. 30 марта 1919 года британские сотрудники правоохранительных органов открыли огонь по собранию безоружных людей, мирно собравшихся, участвовавших в сатьяграхе в Дели. [115]

People rioted in retaliation. On 6 April 1919, a Hindu festival day, Gandhi asked a crowd to remember not to injure or kill British people, but to express their frustration with peace, to boycott British goods and burn any British clothing they owned. He emphasised the use of non-violence to the British and towards each other, even if the other side used violence. Communities across India announced plans to gather in greater numbers to protest. Government warned him not to enter Delhi, but Gandhi defied the order and was arrested on 9 April.[115]

On 13 April 1919, people including women with children gathered in an Amritsar park, and British Indian Army officer Reginald Dyer surrounded them and ordered troops under his command to fire on them. The resulting Jallianwala Bagh massacre (or Amritsar massacre) of hundreds of Sikh and Hindu civilians enraged the subcontinent but was supported by some Britons and parts of the British media as a necessary response. Gandhi in Ahmedabad, on the day after the massacre in Amritsar, did not criticise the British and instead criticised his fellow countrymen for not exclusively using 'love' to deal with the 'hate' of the British government.[115] Gandhi demanded that the Indian people stop all violence, stop all property destruction, and went on fast-to-death to pressure Indians to stop their rioting.[116]

The massacre and Gandhi's non-violent response to it moved many, but also made some Sikhs and Hindus upset that Dyer was getting away with murder. Investigation committees were formed by the British, which Gandhi asked Indians to boycott.[115] The unfolding events, the massacre and the British response, led Gandhi to the belief that Indians will never get a fair equal treatment under British rulers, and he shifted his attention to swaraj and political independence for India.[117] In 1921, Gandhi was the leader of the Indian National Congress.[101] He reorganised the Congress. With Congress now behind Gandhi, and Muslim support triggered by his backing the Khilafat movement to restore the Caliph in Turkey,[101] Gandhi had the political support and the attention of the British Raj.[104][98][100]

Gandhi expanded his nonviolent non-co-operation platform to include the swadeshi policy – the boycott of foreign-made goods, especially British goods. Linked to this was his advocacy that khadi (homespun cloth) be worn by all Indians instead of British-made textiles. Gandhi exhorted Indian men and women, rich or poor, to spend time each day spinning khadi in support of the independence movement.[118] In addition to boycotting British products, Gandhi urged the people to boycott British institutions and law courts, to resign from government employment, and to forsake British titles and honours. Gandhi thus began his journey aimed at crippling the British India government economically, politically and administratively.[119]

The appeal of "Non-cooperation" grew, its social popularity drew participation from all strata of Indian society. Gandhi was arrested on 10 March 1922, tried for sedition, and sentenced to six years' imprisonment. He began his sentence on 18 March 1922. With Gandhi isolated in prison, the Indian National Congress split into two factions, one led by Chitta Ranjan Das and Motilal Nehru favouring party participation in the legislatures, and the other led by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, opposing this move.[120] Furthermore, co-operation among Hindus and Muslims ended as Khilafat movement collapsed with the rise of Atatürk in Turkey. Muslim leaders left the Congress and began forming Muslim organisations. The political base behind Gandhi had broken into factions. He was released in February 1924 for an appendicitis operation, having served only two years.[121][122]

After his early release from prison for political crimes in 1924, Gandhi continued to pursue swaraj over the second half of the 1920s. He pushed through a resolution at the Calcutta Congress in December 1928 calling on the British government to grant India dominion status or face a new campaign of non-cooperation with complete independence for the country as its goal.[123] After Gandhi's support for World War I with Indian combat troops, and the failure of Khilafat movement in preserving the rule of Caliph in Turkey, followed by a collapse in Muslim support for his leadership, some such as Subhas Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh questioned his values and non-violent approach.[100][124] While many Hindu leaders championed a demand for immediate independence, Gandhi revised his own call to a one-year wait, instead of two.[123]

The British did not respond favourably to Gandhi's proposal. British political leaders such as Lord Birkenhead and Winston Churchill announced opposition to "the appeasers of Gandhi" in their discussions with European diplomats who sympathised with Indian demands.[125] On 31 December 1929, an Indian flag was unfurled in Lahore. Gandhi led Congress in a celebration on 26 January 1930 of India's Independence Day in Lahore. This day was commemorated by almost every other Indian organisation. Gandhi then launched a new Satyagraha against the British salt tax in March 1930. He sent an ultimatum in the form of a letter personally addressed to Lord Irwin, the viceroy of India, on 2 March. Gandhi condemned British rule in the letter, describing it as "a curse" that "has impoverished the dumb millions by a system of progressive exploitation and by a ruinously expensive military and civil administration... It has reduced us politically to serfdom." Gandhi also mentioned in the letter that the viceroy received a salary "over five thousand times India's average income." In the letter, Gandhi also stressed his continued adherence to non-violent forms of protest.[126]

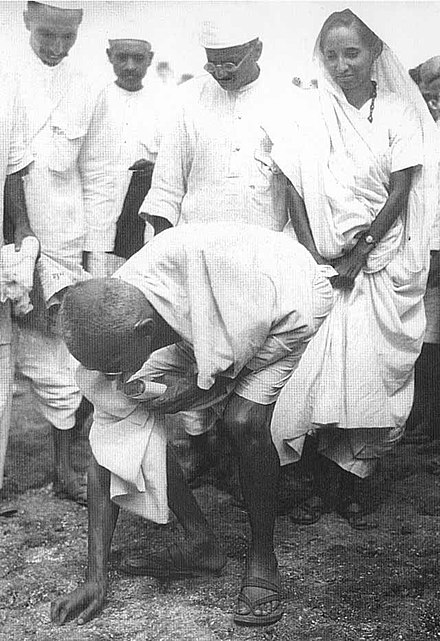

This was highlighted by the Salt March to Dandi from 12 March to 6 April, where, together with 78 volunteers, Gandhi marched 388 kilometres (241 mi) from Ahmedabad to Dandi, Gujarat to make salt himself, with the declared intention of breaking the salt laws. The march took 25 days to cover 240 miles with Gandhi speaking to often huge crowds along the way. Thousands of Indians joined him in Dandi.

According to Sarma, Gandhi recruited women to participate in the salt tax campaigns and the boycott of foreign products, which gave many women a new self-confidence and dignity in the mainstream of Indian public life.[127] However, other scholars such as Marilyn French state that Gandhi barred women from joining his civil disobedience movement because Gandhi feared he would be accused of using women as a political shield.[128] When women insisted on joining the movement and participating in public demonstrations, Gandhi asked the volunteers to get permissions of their guardians and only those women who can arrange child-care should join him.[129] Regardless of Gandhi's apprehensions and views, Indian women joined the Salt March by the thousands to defy the British salt taxes and monopoly on salt mining. On 5 May, Gandhi was interned under a regulation dating from 1827 in anticipation of a protest that he had planned. The protest at Dharasana salt works on 21 May went ahead without Gandhi. A horrified American journalist, Webb Miller, described the British response thus:

In complete silence the Gandhi men drew up and halted a hundred yards from the stockade. A picked column advanced from the crowd, waded the ditches and approached the barbed wire stockade... at a word of command, scores of native policemen rushed upon the advancing marchers and rained blows on their heads with their steel-shot lathis [long bamboo sticks]. Not one of the marchers even raised an arm to fend off blows. They went down like ninepins. From where I stood I heard the sickening whack of the clubs on unprotected skulls... Those struck down fell sprawling, unconscious or writhing with fractured skulls or broken shoulders.[130]

This went on for hours until some 300 or more protesters had been beaten, many seriously injured and two killed. At no time did they offer any resistance. After Gandhi's arrest, the women marched and picketed shops on their own, accepting violence and verbal abuse from British authorities for the cause in the manner Gandhi inspired.[128]

This campaign was one of Gandhi's most successful at upsetting British hold on India; Britain responded by imprisoning over 60,000 people.[131] However, Congress estimates put the figure at 90,000. Among them was one of Gandhi's lieutenants, Jawaharlal Nehru.

Indian Congress in the 1920s appealed to Andhra Pradesh peasants by creating Telugu language plays that combined Indian mythology and legends, linked them to Gandhi's ideas, and portrayed Gandhi as a messiah, a reincarnation of ancient and medieval Indian nationalist leaders and saints. The plays built support among peasants steeped in traditional Hindu culture, according to Murali, and this effort made Gandhi a folk hero in Telugu speaking villages, a sacred messiah-like figure.[132]

According to Dennis Dalton, it was Gandhi's ideas that were responsible for his wide following. Gandhi criticised Western civilisation as one driven by "brute force and immorality", contrasting it with his categorisation of Indian civilisation as one driven by "soul force and morality."[133] Gandhi captured the imagination of the people of his heritage with his ideas about winning "hate with love." These ideas are evidenced in his pamphlets from the 1890s, in South Africa, where too Gandhi was popular among the Indian indentured workers. After he returned to India, people flocked to Gandhi because he reflected their values.[133]

Gandhi also campaigned hard going from one rural corner of the Indian subcontinent to another. He used terminology and phrases such as Rama-rajya from Ramayana, Prahlada as a paradigmatic icon, and such cultural symbols as another facet of swaraj and satyagraha.[134] During Gandhi's lifetime, these ideas sounded strange outside India, but they readily and deeply resonated with the culture and historic values of his people.[133][135]

The government, represented by Lord Irwin, decided to negotiate with Gandhi. The Gandhi–Irwin Pact was signed in March 1931. The British Government agreed to free all political prisoners, in return for the suspension of the civil disobedience movement. According to the pact, Gandhi was invited to attend the Round Table Conference in London for discussions and as the sole representative of the Indian National Congress. The conference was a disappointment to Gandhi and the nationalists. Gandhi expected to discuss India's independence, while the British side focused on the Indian princes and Indian minorities rather than on a transfer of power. Lord Irwin's successor, Lord Willingdon, took a hard line against India as an independent nation, began a new campaign of controlling and subduing the nationalist movement. Gandhi was again arrested, and the government tried and failed to negate his influence by completely isolating him from his followers.[136]

In Britain, Winston Churchill, a prominent Conservative politician who was then out of office but later became its prime minister, became a vigorous and articulate critic of Gandhi and opponent of his long-term plans. Churchill often ridiculed Gandhi, saying in a widely reported 1931 speech:

It is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr Gandhi, a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the Vice-regal palace....to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor.[137]

Churchill's bitterness against Gandhi grew in the 1930s. He called Gandhi as the one who was "seditious in aim" whose evil genius and multiform menace was attacking the British empire. Churchill called him a dictator, a "Hindu Mussolini", fomenting a race war, trying to replace the Raj with Brahmin cronies, playing on the ignorance of Indian masses, all for selfish gain.[138] Churchill attempted to isolate Gandhi, and his criticism of Gandhi was widely covered by European and American press. It gained Churchill sympathetic support, but it also increased support for Gandhi among Europeans. The developments heightened Churchill's anxiety that the "British themselves would give up out of pacifism and misplaced conscience."[138]

During the discussions between Gandhi and the British government over 1931–32 at the Round Table Conferences, Gandhi, now aged about 62, sought constitutional reforms as a preparation to the end of colonial British rule, and begin the self-rule by Indians.[139] The British side sought reforms that would keep the Indian subcontinent as a colony. The British negotiators proposed constitutional reforms on a British Dominion model that established separate electorates based on religious and social divisions. The British questioned the Congress party and Gandhi's authority to speak for all of India.[140] They invited Indian religious leaders, such as Muslims and Sikhs, to press their demands along religious lines, as well as B. R. Ambedkar as the representative leader of the untouchables.[139] Gandhi vehemently opposed a constitution that enshrined rights or representations based on communal divisions, because he feared that it would not bring people together but divide them, perpetuate their status, and divert the attention from India's struggle to end the colonial rule.[141][142]

The Second Round Table conference was the only time Gandhi left India between 1914 and his death in 1948. Gandhi declined the government's offer of accommodation in an expensive West End hotel, preferring to stay in the East End, to live among working-class people, as he did in India.[143] Gandhi based himself in a small cell-bedroom at Kingsley Hall for the three-month duration of his stay and was enthusiastically received by East Enders.[144] During this time, Gandhi renewed his links with the British vegetarian movement.

After Gandhi returned from the Second Round Table conference, he started a new satyagraha. Gandhi was arrested and imprisoned at the Yerwada Jail, Pune. While he was in prison, the British government enacted a new law that granted untouchables a separate electorate. It came to be known as the Communal Award.[145] In protest, Gandhi started a fast-unto-death, while he was held in prison.[146] The resulting public outcry forced the government, in consultations with Ambedkar, to replace the Communal Award with a compromise Poona Pact.[147][148]

In 1934, Gandhi resigned from Congress party membership. He did not disagree with the party's position, but felt that if he resigned, Gandhi's popularity with Indians would cease to stifle the party's membership, which actually varied, including communists, socialists, trade unionists, students, religious conservatives, and those with pro-business convictions, and that these various voices would get a chance to make themselves heard. Gandhi also wanted to avoid being a target for Raj propaganda by leading a party that had temporarily accepted political accommodation with the Raj.[149]

In 1936, Gandhi returned to active politics again with the Nehru presidency and the Lucknow session of the Congress. Although Gandhi wanted a total focus on the task of winning independence and not speculation about India's future, he did not restrain the Congress from adopting socialism as its goal. Gandhi had a clash with Subhas Chandra Bose, who had been elected president in 1938, and who had previously expressed a lack of faith in nonviolence as a means of protest.[150] Despite Gandhi's opposition, Bose won a second term as Congress President, against Gandhi's nominee, Bhogaraju Pattabhi Sitaramayya. Gandhi declared that Sitaramayya's defeat was his defeat.[151] Bose later left the Congress when the All-India leaders resigned en masse in protest of his abandonment of the principles introduced by Gandhi.[152][153]

Gandhi opposed providing any help to the British war effort and he campaigned against any Indian participation in World War II.[154] The British government responded with the arrests of Gandhi and many other Congress leaders and killed over 1,000 Indians who participated in this movement.[155] A number of violent attacks were also carried out by the nationalists against the British government.[156] While Gandhi's campaign did not enjoy the support of a number of Indian leaders, and over 2.5 million Indians volunteered and joined the British military to fight on various fronts of the Allied Forces, the movement played a role in weakening the control over the South Asian region by the British regime and it ultimately paved the way for Indian independence.[154][156]

Gandhi's opposition to the Indian participation in World War II was motivated by his belief that India could not be party to a war ostensibly being fought for democratic freedom while that freedom was denied to India itself.[157] Gandhi also condemned Nazism and Fascism, a view which won endorsement of other Indian leaders. As the war progressed, Gandhi intensified his demand for independence, calling for the British to Quit India in a 1942 speech in Mumbai.[158] This was Gandhi's and the Congress Party's most definitive revolt aimed at securing the British exit from India.[159] The British government responded quickly to the Quit India speech, and within hours after Gandhi's speech arrested Gandhi and all the members of the Congress Working Committee.[160] His countrymen retaliated the arrests by damaging or burning down hundreds of government owned railway stations, police stations, and cutting down telegraph wires.[161]

In 1942, Gandhi now nearing age 73, urged his people to completely stop co-operating with the imperial government. In this effort, Gandhi urged that they neither kill nor injure British people but be willing to suffer and die if violence is initiated by the British officials.[158] He clarified that the movement would not be stopped because of any individual acts of violence, saying that the "ordered anarchy" of "the present system of administration" was "worse than real anarchy."[162][163] Gandhi urged Indians to karo ya maro ("do or die") in the cause of their rights and freedoms.[158][164]

Gandhi's arrest lasted two years, as he was held in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. During this period, Gandhi's longtime secretary Mahadev Desai died of a heart attack, his wife Kasturba died after 18 months' imprisonment on 22 February 1944, and Gandhi suffered a severe malaria attack.[161] While in jail, he agreed to an interview with Stuart Gelder, a British journalist. Gelder then composed and released an interview summary, cabled it to the mainstream press, that announced sudden concessions Gandhi was willing to make, comments that shocked his countrymen, the Congress workers and even Gandhi. The latter two claimed that it distorted what Gandhi actually said on a range of topics and falsely repudiated the Quit India movement.[161]

Gandhi was released before the end of the war on 6 May 1944 because of his failing health and necessary surgery; the Raj did not want him to die in prison and enrage the nation. Gandhi came out of detention to an altered political scene – the Muslim League for example, which a few years earlier had appeared marginal, "now occupied the centre of the political stage"[165] and the topic of Jinnah's campaign for Pakistan was a major talking point. Gandhi and Jinnah had extensive correspondence and the two men met several times over a period of two weeks in September 1944 at Jinnah's house in Bombay, where Gandhi insisted on a united religiously plural and independent India which included Muslims and non-Muslims of the Indian subcontinent coexisting. Jinnah rejected this proposal and insisted instead for partitioning the subcontinent on religious lines to create a separate Muslim homeland (later Pakistan).[166] These discussions continued through 1947.[167]

While the leaders of Congress languished in jail, the other parties supported the war and gained organisational strength. Underground publications flailed at the ruthless suppression of Congress, but it had little control over events.[168] At the end of the war, the British gave clear indications that power would be transferred to Indian hands. At this point, Gandhi called off the struggle, and around 100,000 political prisoners were released, including the Congress's leadership.[169]

Gandhi opposed the partition of the Indian subcontinent along religious lines.[166][170][171] The Indian National Congress and Gandhi called for the British to Quit India. However, the All-India Muslim League demanded "Divide and Quit India."[172][173] Gandhi suggested an agreement which required the Congress and the Muslim League to co-operate and attain independence under a provisional government, thereafter, the question of partition could be resolved by a plebiscite in the districts with a Muslim majority.[174]

Jinnah rejected Gandhi's proposal and called for Direct Action Day, on 16 August 1946, to press Muslims to publicly gather in cities and support his proposal for the partition of the Indian subcontinent into a Muslim state and non-Muslim state. Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the Muslim League Chief Minister of Bengal – now Bangladesh and West Bengal, gave Calcutta's police special holiday to celebrate the Direct Action Day.[175] The Direct Action Day triggered a mass murder of Calcutta Hindus and the torching of their property, and holidaying police were missing to contain or stop the conflict.[176] The British government did not order its army to move in to contain the violence.[175] The violence on Direct Action Day led to retaliatory violence against Muslims across India. Thousands of Hindus and Muslims were murdered, and tens of thousands were injured in the cycle of violence in the days that followed.[177] Gandhi visited the most riot-prone areas to appeal a stop to the massacres.[176]

.jpg/440px-Mountbattens_with_Gandhi_(IND_5298).jpg)

Archibald Wavell, the Viceroy and Governor-General of British India for three years through February 1947, had worked with Gandhi and Jinnah to find a common ground, before and after accepting Indian independence in principle. Wavell condemned Gandhi's character and motives as well as his ideas. Wavell accused Gandhi of harbouring the single-minded idea to "overthrow British rule and influence and to establish a Hindu raj", and called Gandhi a "malignant, malevolent, exceedingly shrewd" politician.[178] Wavell feared a civil war on the Indian subcontinent, and doubted Gandhi would be able to stop it.[178]

The British reluctantly agreed to grant independence to the people of the Indian subcontinent, but accepted Jinnah's proposal of partitioning the land into Pakistan and India. Gandhi was involved in the final negotiations, but Stanley Wolpert states the "plan to carve up British India was never approved of or accepted by Gandhi".[179]

The partition was controversial and violently disputed. More than half a million were killed in religious riots as 10 million to 12 million non-Muslims (Hindus and Sikhs mostly) migrated from Pakistan into India, and Muslims migrated from India into Pakistan, across the newly created borders of India, West Pakistan and East Pakistan.[180]

Gandhi spent the day of independence not celebrating the end of the British rule, but appealing for peace among his countrymen by fasting and spinning in Calcutta on 15 August 1947. The partition had gripped the Indian subcontinent with religious violence and the streets were filled with corpses.[181] Gandhi's fasting and protests are credited for stopping the religious riots and communal violence.[178][182][183][184][185][186][187][188][189]

At 5:17 p.m. on 30 January 1948, Gandhi was with his grandnieces in the garden of Birla House (now Gandhi Smriti), on his way to address a prayer meeting, when Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist, fired three bullets into Gandhi's chest from a pistol at close range.[190][191] According to some accounts, Gandhi died instantly.[192][193] In other accounts, such as one prepared by an eyewitness journalist, Gandhi was carried into the Birla House, into a bedroom. There, he died about 30 minutes later as one of Gandhi's family members read verses from Hindu scriptures.[194][195][196][197][182]

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru addressed his countrymen over the All-India Radio saying:[198]

Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there is darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the nation, is no more. Perhaps I am wrong to say that; nevertheless, we will not see him again, as we have seen him for these many years, we will not run to him for advice or seek solace from him, and that is a terrible blow, not only for me, but for millions and millions in this country.[199]

Godse, a Hindu nationalist,[200][191][201] with links to the Hindu Mahasabha and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh,[202][203][204][205][182] made no attempt to escape; several other conspirators were soon arrested as well. The accused were Nathuram Vinayak Godse, Narayan Apte, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Shankar Kistayya, Dattatraya Parchure, Vishnu Karkare, Madanlal Pahwa, and Gopal Godse.[182][205][206][207][208][209]

The trial began on 27 May 1948 and ran for eight months before Justice Atma Charan passed his final order on 10 February 1949. The prosecution called 149 witnesses, the defence none.[210] The court found all of the defendants except one guilty as charged. Eight men were convicted for the murder conspiracy, and others were convicted for violation of the Explosive Substances Act. Savarkar was acquitted and set free. Nathuram Godse and Narayan Apte were sentenced to death by hanging[211] while the remaining six (including Godse's brother, Gopal) were sentenced to life imprisonment.[212]

Gandhi's death was mourned nationwide.[195][196][197][182] Over a million people joined the five-mile-long funeral procession that took over five hours to reach Raj Ghat from Birla house, where Gandhi was assassinated, and another million watched the procession pass by.[213] His body was transported on a weapons carrier, whose chassis was dismantled overnight to allow a high-floor to be installed so that people could catch a glimpse of Gandhi's body. The engine of the vehicle was not used; instead, four drag-ropes held by 50 people each pulled the vehicle.[214] All Indian-owned establishments in London remained closed in mourning as thousands of people from all faiths and denominations and Indians from all over Britain converged at India House in London.[215]

Gandhi was cremated in accordance with Hindu tradition. His ashes were poured into urns which were sent across India for memorial services.[217] Most of the ashes were immersed at the Sangam at Allahabad on 12 February 1948, but some were secretly taken away. In 1997, Tushar Gandhi immersed the contents of one urn, found in a bank vault and reclaimed through the courts, at the Sangam at Allahabad.[218][219] Some of Gandhi's ashes were scattered at the source of the Nile River near Jinja, Uganda, and a memorial plaque marks the event. On 30 January 2008, the contents of another urn were immersed at Girgaum Chowpatty. Another urn is at the palace of the Aga Khan in Pune (where Gandhi was held as a political prisoner from 1942 to 1944[220][221]) and another in the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine in Los Angeles.[218][222][223]

The Birla House site where Gandhi was assassinated is now a memorial called Gandhi Smriti. The place near Yamuna River where he was cremated is the Rāj Ghāt memorial in New Delhi.[224] A black marble platform, it bears the epigraph "Hē Rāma" (Devanagari: हे ! राम or, Hey Raam). These are said to be Gandhi's last words after he was shot.[225]

Gandhi's spirituality was greatly based on his embracement of the five great vows of Jainism and Hindu Yoga philosophy, viz. Satya (truth), ahimsa (nonviolence), brahmacharya (celibacy), asteya (non-stealing), and aparigraha (non-attachment).[226] He stated that "Unless you impose on yourselves the five vows you may not embark on the experiment at all."[226] Gandhi's statements, letters and life have attracted much political and scholarly analysis of his principles, practices and beliefs, including what influenced him. Some writers present Gandhi as a paragon of ethical living and pacifism, while others present him as a more complex, contradictory and evolving character influenced by his culture and circumstances.[227][228]

Gandhi dedicated his life to discovering and pursuing truth, or Satya, and called his movement satyagraha, which means "appeal to, insistence on, or reliance on the Truth."[229] The first formulation of the satyagraha as a political movement and principle occurred in 1920, which Gandhi tabled as "Resolution on Non-cooperation" in September that year before a session of the Indian Congress. It was the satyagraha formulation and step, states Dennis Dalton, that deeply resonated with beliefs and culture of his people, embedded him into the popular consciousness, transforming him quickly into Mahatma.[230]

Gandhi based Satyagraha on the Vedantic ideal of self-realisation, ahimsa (nonviolence), vegetarianism, and universal love. William Borman states that the key to his satyagraha is rooted in the Hindu Upanishadic texts.[231] According to Indira Carr, Gandhi's ideas on ahimsa and satyagraha were founded on the philosophical foundations of Advaita Vedanta.[232] I. Bruce Watson states that some of these ideas are found not only in traditions within Hinduism, but also in Jainism or Buddhism, particularly those about non-violence, vegetarianism and universal love, but Gandhi's synthesis was to politicise these ideas.[233] His concept of satya as a civil movement, states Glyn Richards, are best understood in the context of the Hindu terminology of Dharma and Ṛta.[234]

Gandhi stated that the most important battle to fight was overcoming his own demons, fears, and insecurities. Gandhi summarised his beliefs first when he said, "God is Truth." Gandhi would later change this statement to "Truth is God." Thus, satya (truth) in Gandhi's philosophy is "God".[235] Gandhi, states Richards, described the term "God" not as a separate power, but as the Being (Brahman, Atman) of the Advaita Vedanta tradition, a nondual universal that pervades in all things, in each person and all life.[234] According to Nicholas Gier, this to Gandhi meant the unity of God and humans, that all beings have the same one soul and therefore equality, that atman exists and is same as everything in the universe, ahimsa (non-violence) is the very nature of this atman.[236]

The essence of Satyagraha is "soul force" as a political means, refusing to use brute force against the oppressor, seeking to eliminate antagonisms between the oppressor and the oppressed, aiming to transform or "purify" the oppressor. It is not inaction but determined passive resistance and non-co-operation where, states Arthur Herman, "love conquers hate".[239] A euphemism sometimes used for Satyagraha is that it is a "silent force" or a "soul force" (a term also used by Martin Luther King Jr. during his "I Have a Dream" speech). It arms the individual with moral power rather than physical power. Satyagraha is also termed a "universal force", as it essentially "makes no distinction between kinsmen and strangers, young and old, man and woman, friend and foe."[e]

Gandhi wrote: "There must be no impatience, no barbarity, no insolence, no undue pressure. If we want to cultivate a true spirit of democracy, we cannot afford to be intolerant. Intolerance betrays want of faith in one's cause."[243] Civil disobedience and non-co-operation as practised under Satyagraha are based on the "law of suffering",[244] a doctrine that the endurance of suffering is a means to an end. This end usually implies a moral upliftment or progress of an individual or society. Therefore, non-co-operation in Satyagraha is in fact a means to secure the co-operation of the opponent consistently with truth and justice.[245]

While Gandhi's idea of satyagraha as a political means attracted a widespread following among Indians, the support was not universal. For example, Muslim leaders such as Jinnah opposed the satyagraha idea, accused Gandhi to be reviving Hinduism through political activism, and began effort to counter Gandhi with Muslim nationalism and a demand for Muslim homeland.[246][247][248] The untouchability leader Ambedkar, in June 1945, after his decision to convert to Buddhism and the first Law and Justice minister of modern India, dismissed Gandhi's ideas as loved by "blind Hindu devotees", primitive, influenced by spurious brew of Tolstoy and Ruskin, and "there is always some simpleton to preach them".[249][250][251] Winston Churchill caricatured Gandhi as a "cunning huckster" seeking selfish gain, an "aspiring dictator", and an "atavistic spokesman of a pagan Hinduism." Churchill stated that the civil disobedience movement spectacle of Gandhi only increased "the danger to which white people there [British India] are exposed."[252]

Although Gandhi was not the originator of the principle of nonviolence, he was the first to apply it in the political field on a large scale.[253][254] The concept of nonviolence (ahimsa) has a long history in Indian religious thought, and is considered the highest dharma (ethical value/virtue), a precept to be observed towards all living beings (sarvbhuta), at all times (sarvada), in all respects (sarvatha), in action, words and thought.[255] Gandhi explains his philosophy and ideas about ahimsa as a political means in his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth.[256][257][258][259]

Although Gandhi considered non-violence to be "infinitely superior to violence", he preferred violence to cowardice.[260][261] Gandhi added that he "would rather have India resort to arms in order to defend her honor than that she should in a cowardly manner become or remain a helpless witness to her own dishonor."[261]

Gandhi was a prolific writer. His signature style was simple, precise, clear and as devoid of artificialities.[262] One of Gandhi's earliest publications, Hind Swaraj, published in Gujarati in 1909, became "the intellectual blueprint" for India's independence movement. The book was translated into English the next year, with a copyright legend that read "No Rights Reserved".[263] For decades, Gandhi edited several newspapers including Harijan in Gujarati, in Hindi and in the English language; Indian Opinion while in South Africa and, Young India, in English, and Navajivan, a Gujarati monthly, on his return to India. Later, Navajivan was also published in Hindi. Gandhi also wrote letters almost every day to individuals and newspapers.[264]

Gandhi also wrote several books, including his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth (Gujarātī "સત્યના પ્રયોગો અથવા આત્મકથા"), of which Gandhi bought the entire first edition to make sure it was reprinted.[265] His other autobiographies included: Satyagraha in South Africa about his struggle there, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, a political pamphlet, and a paraphrase in Gujarati of John Ruskin's Unto This Last which was an early critique of political economy.[266] This last essay can be considered his programme on economics. Gandhi also wrote extensively on vegetarianism, diet and health, religion, social reforms, etc. Gandhi usually wrote in Gujarati, though he also revised the Hindi and English translations of his books.[267] In 1934, Gandhi wrote Songs from Prison while prisoned in Yerawada jail in Maharashtra.[268]

Gandhi's complete works were published by the Indian government under the name The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi in the 1960s. The writings comprise about 50,000 pages published in about 100 volumes. In 2000, a revised edition of the complete works sparked a controversy, as it contained a large number of errors and omissions.[269] The Indian government later withdrew the revised edition.[270]

Gandhi is noted as the greatest figure of the successful Indian independence movement against the British rule. He is also hailed as the greatest figure of modern India.[f] American historian Stanley Wolpert described Gandhi as "India's greatest revolutionary nationalist leader" and the greatest Indian since the Buddha.[277] In 1999, Gandhi was named "Asian of the century" by Asiaweek.[278] In a 2000 BBC poll, he was voted as the greatest man of the millennium.[279][280]

The word Mahatma, while often mistaken for Gandhi's given name in the West, is taken from the Sanskrit words maha (meaning Great) and atma (meaning Soul).[281][282] He was publicly bestowed with the honorific title "Mahatma" in July 1914 at farewell meeting in Town Hall, Durban.[283][284] Rabindranath Tagore is said to have accorded the title to Gandhi by 1915.[285][g] In his autobiography, Gandhi nevertheless explains that he never valued the title, and was often pained by it.[288][289][290]

Innumerable streets, roads, and localities in India are named after Gandhi. These include M.G.Road (the main street of a number of Indian cities including Mumbai, Bangalore, Kolkata, Lucknow, Kanpur, Gangtok and Indore), Gandhi Market (near Sion, Mumbai) and Gandhinagar (the capital of the state of Gujarat, Gandhi's birthplace).[292]

As of 2008, over 150 countries have released stamps on Gandhi.[293] In October 2019, about 87 countries including Turkey, the United States, Russia, Iran, Uzbekistan, and Palestine released commemorative Gandhi stamps on the 150th anniversary of his birth.[294][295][296][297]

In 2014, Brisbane's Indian community commissioned a statue of Gandhi, created by Ram V. Sutar and Anil Sutar in the Roma Street Parkland,[298][299] It was unveiled by Narendra Modi, then Prime Minister of India.

Florian asteroid 120461 Gandhi was named in his honour in September 2020.[300] In October 2022, a statue of Gandhi was installed in Astana on the embankment of the rowing canal, opposite the cult monument to the defenders of Kazakhstan.[301]

On 15 December 2022, the United Nations headquarters in New York unveiled the statue of Gandhi. UN Secretary-General António Guterres called Gandhi an "uncompromising advocate for peaceful co-existence."[302]

Gandhi influenced important leaders and political movements.[259] Leaders of the civil rights movement in the United States, including Martin Luther King Jr., James Lawson, and James Bevel, drew from the writings of Gandhi in the development of their own theories about nonviolence.[303][304][305] King said, "Christ gave us the goals and Mahatma Gandhi the tactics."[306] King sometimes referred to Gandhi as "the little brown saint."[307] Anti-apartheid activist and former President of South Africa, Nelson Mandela, was inspired by Gandhi.[308] Others include Steve Biko, Václav Havel,[309] and Aung San Suu Kyi.[310]

In his early years, the former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela was a follower of the nonviolent resistance philosophy of Gandhi.[308] Bhana and Vahed commented on these events as "Gandhi inspired succeeding generations of South African activists seeking to end White rule. This legacy connects him to Nelson Mandela...in a sense, Mandela completed what Gandhi started."[311]

Gandhi's life and teachings inspired many who specifically referred to Gandhi as their mentor or who dedicated their lives to spreading his ideas. In Europe, Romain Rolland was the first to discuss Gandhi in his 1924 book Mahatma Gandhi, and Brazilian anarchist and feminist Maria Lacerda de Moura wrote about Gandhi in her work on pacifism. In 1931, physicist Albert Einstein exchanged letters with Gandhi and called him "a role model for the generations to come" in a letter writing about him.[312] Einstein said of Gandhi:

Mahatma Gandhi's life achievement stands unique in political history. He has invented a completely new and humane means for the liberation war of an oppressed country, and practised it with greatest energy and devotion. The moral influence he had on the consciously thinking human being of the entire civilised world will probably be much more lasting than it seems in our time with its overestimation of brutal violent forces. Because lasting will only be the work of such statesmen who wake up and strengthen the moral power of their people through their example and educational works. We may all be happy and grateful that destiny gifted us with such an enlightened contemporary, a role model for the generations to come. Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this walked the earth in flesh and blood.

Farah Omar, a political activist from Somaliland, visited India in 1930, where he met Gandhi and was influenced by Gandhi's non-violent philosophy, which he adopted in his campaign in British Somaliland.[313]

Lanza del Vasto went to India in 1936 intending to live with Gandhi; he later returned to Europe to spread Gandhi's philosophy and founded the Community of the Ark in 1948 (modelled after Gandhi's ashrams). Madeleine Slade (known as "Mirabehn") was the daughter of a British admiral who spent much of her adult life in India as a devotee of Gandhi.[314][315]

In addition, the British musician John Lennon referred to Gandhi when discussing his views on nonviolence.[316] In 2007, former US Vice-President and environmentalist Al Gore drew upon Gandhi's idea of satyagraha in a speech on climate change.[317] 44th President of the United States Barack Obama said in September 2009 that his biggest inspiration came from Gandhi. His reply was in response to the question: "Who was the one person, dead or live, that you would choose to dine with?" Obama added, "He's somebody I find a lot of inspiration in. He inspired Dr. King with his message of nonviolence. He ended up doing so much and changed the world just by the power of his ethics."[318]

Time magazine named The 14th Dalai Lama, Lech Wałęsa, Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, Aung San Suu Kyi, Benigno Aquino Jr., Desmond Tutu, and Nelson Mandela as Children of Gandhi and his spiritual heirs to nonviolence.[319] The Mahatma Gandhi District in Houston, Texas, United States, an ethnic Indian enclave, is officially named after Gandhi.[320]

Gandhi's ideas had a significant influence on 20th-century philosophy. It began with his engagement with Romain Rolland and Martin Buber. Jean-Luc Nancy said that the French philosopher Maurice Blanchot engaged critically with Gandhi from the point of view of "European spirituality."[321] Since then philosophers including Hannah Arendt, Etienne Balibar and Slavoj Žižek found that Gandhi was a necessary reference to discuss morality in politics. American political scientist Gene Sharp wrote an analytical text, Gandhi as a political strategist, on the significance of Gandhi's ideas, for creating nonviolent social change. Recently, in the light of climate change, Gandhi's views on technology are gaining importance in the fields of environmental philosophy and philosophy of technology.[321]

In 2007, the United Nations General Assembly declared Gandhi's birthday, 2 October, as "the International Day of Nonviolence."[322] First proposed by UNESCO in 1948, as the School Day of Nonviolence and Peace (DENIP in Spanish),[323] 30 January is observed as the School Day of Nonviolence and Peace in schools of many countries.[324] In countries with a Southern Hemisphere school calendar, it is observed on 30 March.[324]

Time magazine named Gandhi the Man of the Year in 1930.[280] In the same magazine's 1999 list of The Most Important People of the Century, Gandhi was second only to Albert Einstein, who had called Gandhi "the greatest man of our age."[325] The University of Nagpur awarded him an LL.D. in 1937.[326] The Government of India awarded the annual Gandhi Peace Prize to distinguished social workers, world leaders and citizens. Nelson Mandela, the leader of South Africa's struggle to eradicate racial discrimination and segregation, was a prominent non-Indian recipient. In 2003, Gandhi was posthumously awarded with the World Peace Prize.[327] Two years later, he was posthumously awarded with the Order of the Companions of O. R. Tambo.[328] In 2011, Gandhi topped the TIME's list of top 25 political icons of all time.[329]