Англиканство — западная христианская традиция , которая развилась из практик, литургии и идентичности Церкви Англии после Английской Реформации , [1] в контексте Протестантской Реформации в Европе. Это одна из крупнейших ветвей христианства , насчитывающая около 110 миллионов последователей по всему миру по состоянию на 2001 год [update]. [2] [3]

Приверженцы англиканства называются англиканами ; в некоторых странах их также называют епископалами . Большинство англикан являются членами национальных или региональных церковных провинций международного англиканского сообщества , [4] которое образует третью по величине христианскую общину в мире после католической церкви и Восточной православной церкви , [5] и самую большую в мире протестантскую общину. Эти провинции находятся в полном общении с Кентерберийским престолом и, таким образом, с архиепископом Кентерберийским , которого община называет своим primus inter pares ( лат . «первый среди равных»). Архиепископ созывает десятилетнюю Ламбетскую конференцию , председательствует на собрании примасов и является президентом Англиканского консультативного совета . [6] [7] Некоторые церкви, не входящие в Англиканское сообщество или не признанные им, также называют себя англиканскими, включая те, которые находятся в рамках Продолжающегося англиканского движения и Англиканской перестройки . [8]

Англиканцы основывают свою христианскую веру на Библии , традициях апостольской церкви, апостольской преемственности («исторический епископат») и писаниях отцов церкви , а также исторически на Тридцати девяти статьях религии и Книгах проповедей . [9] [1] Англиканство образует ветвь западного христианства , окончательно провозгласив свою независимость от Святого Престола во времена Елизаветинского религиозного урегулирования . [10] Многие из англиканских формулировок середины XVI века тесно соответствуют формулировкам исторического протестантизма . Эти реформы были поняты одним из тех, кто наиболее ответственен за них, Томасом Кранмером , архиепископом Кентерберийским , и другими как навигация по срединному пути между двумя формирующимися протестантскими традициями, а именно лютеранством и кальвинизмом . [11]

В первой половине XVII века Церковь Англии и связанная с ней Церковь Ирландии были представлены некоторыми англиканскими богословами как составляющие отдельную христианскую традицию с теологией, структурами и формами поклонения, представляющими собой другой вид срединного пути или via media , первоначально между лютеранством и кальвинизмом [12], а затем между протестантизмом и католицизмом — точка зрения, которая стала весьма влиятельной в более поздних теориях англиканской идентичности и выражена в описании англиканства как «католического и реформированного». [13] Степень различия между протестантскими и католическими тенденциями в англиканстве обычно является предметом дебатов как в рамках отдельных англиканских церквей, так и в англиканском сообществе. Книга общих молитв уникальна для англиканства, это собрание служб в одном молитвеннике, используемом на протяжении столетий. Книга признана основной связью, которая связывает англиканское сообщество как литургическую традицию. [9]

После Американской революции англиканские общины в Соединенных Штатах и Британской Северной Америке (которые позже станут основой для современной страны Канада) были преобразованы в автономные церкви со своими епископами и самоуправляемыми структурами; они были известны как Американская епископальная церковь и Церковь Англии в Доминионе Канада . Благодаря расширению Британской империи и деятельности христианских миссий эта модель была принята в качестве модели для многих вновь образованных церквей, особенно в Африке, Австралазии и Азиатско-Тихоокеанском регионе. В 19 веке был придуман термин англиканство для описания общей религиозной традиции этих церквей, а также Шотландской епископальной церкви , которая, хотя и возникла ранее в Церкви Шотландии , стала признаваться разделяющей эту общую идентичность.

Слово «англиканский» происходит от Anglicana ecclesia libera sit , фразы из Великой хартии вольностей от 15 июня 1215 года, означающей «Английская церковь будет свободна». [14] Приверженцы англиканства называются англиканами . Как прилагательное, «англиканский» используется для описания людей, учреждений, церквей, литургических традиций и теологических концепций, разработанных Церковью Англии. [7]

Как существительное, англиканин — это член церкви в англиканском сообществе. Это слово также используется последователями отделенных групп, которые покинули сообщество или были основаны отдельно от него. Слово изначально относилось только к учениям и обрядам христиан по всему миру, находящимся в общении с епархией Кентербери , но иногда стало распространяться на любую церковь, следующую этим традициям, а не на фактическое членство в англиканском сообществе. [7]

Хотя термин «англиканская» упоминается в отношении Церкви Англии еще в XVI веке, его использование не стало общепринятым до второй половины XIX века. В британском парламентском законодательстве, ссылающемся на Английскую установленную церковь , нет необходимости в описании; это просто Церковь Англии, хотя слово «протестантская» используется во многих правовых актах, определяющих наследование короны и квалификацию для должности. Когда Акт об унии с Ирландией создал Объединенную церковь Англии и Ирландии, было указано, что она будет единой «протестантской епископальной церковью», тем самым отличая ее форму церковного управления от пресвитерианского государственного устройства, которое преобладает в Церкви Шотландии . [15]

Слово «епископальная» предпочтительнее в названии Епископальной церкви (провинции Англиканского сообщества, охватывающей Соединенные Штаты) и Шотландской епископальной церкви , хотя полное название первой — Протестантская епископальная церковь в Соединенных Штатах Америки . Однако в других местах термин «англиканская церковь» стал предпочтительнее, поскольку он отличал эти церкви от других, которые поддерживают епископальное устройство .

В своих структурах, теологии и формах поклонения англиканство возникло как отдельная христианская традиция, представляющая собой нечто среднее между лютеранскими и реформатскими разновидностями протестантизма ; [16] после Оксфордского движения англиканство часто характеризовалось как представляющее собой via media («срединный путь») между протестантизмом в целом и католицизмом. [12]

Вера англикан основана на Священном Писании и Евангелии , традициях Апостольской Церкви, историческом епископате , первых четырёх Вселенских соборах [ 17] и ранних Отцах Церкви , особенно тех, которые действовали в течение пяти первых веков христианства, в соответствии с принципом квинквасекуляризма, предложенным английским епископом Ланселотом Эндрюсом и лютеранским диссидентом Георгом Каликстом .

Англикане понимают Ветхий и Новый Заветы как «содержащие все необходимое для спасения» и как правило и высший стандарт веры. [18] Разум и традиция рассматриваются как ценные средства толкования Писания (позиция, впервые подробно сформулированная Ричардом Хукером ), но среди англикан нет полного взаимного согласия относительно того, как именно взаимодействуют (или должны взаимодействовать) Писание, разум и традиция. [19] Англикане понимают Апостольский Символ веры как символ крещения, а Никейский Символ веры как достаточное утверждение христианской веры .

Англикане верят, что католическая и апостольская вера раскрыта в Священном Писании и вселенских символах веры (Апостольском, Никейском и Афанасиевском) и интерпретируют их в свете христианской традиции исторической церкви, учености, разума и опыта. [20]

Англиканцы празднуют традиционные таинства, уделяя особое внимание Евхаристии , также называемой Святым Причастием, Вечерей Господней или Мессой . Евхаристия занимает центральное место в богослужении для большинства англикан как общее приношение молитвы и хвалы, в котором жизнь, смерть и воскресение Иисуса Христа провозглашаются через молитву, чтение Библии, пение, благодарение Богу над хлебом и вином за бесчисленные блага, полученные через страдания Христа; преломление хлеба, благословение чаши и принятие тела и крови Христа, как установлено на Тайной Вечере . Освященный хлеб и вино, которые англиканские формулировки считают истинным телом и кровью Христа в духовном смысле и внешними символами внутренней благодати, данной Христом, которые кающемуся передают прощение и очищение от греха. Хотя многие англиканцы празднуют Евхаристию аналогично преобладающей латино-католической традиции, допускается значительная степень литургической свободы, а стили богослужения варьируются от простых до сложных. [ необходима цитата ]

Уникальной для англиканства является Книга общей молитвы (BCP), сборник служб, которые верующие в большинстве англиканских церквей использовали на протяжении столетий. Первоначально она называлась общей молитвой , потому что предназначалась для использования во всех церквях Церкви Англии, которые ранее следовали различным местным литургиям. Термин сохранился, когда церковь стала международной, потому что все англикане использовали ее по всему миру.

В 1549 году Томас Кранмер , тогдашний архиепископ Кентерберийский , составил первую Книгу общих молитв . Хотя с тех пор она претерпела множество изменений, а англиканские церкви в разных странах разработали другие молитвенники, Книга молитв по-прежнему признается одной из связей, которые объединяют англикан.

.jpg/440px-Saint_Alban_(cropped).jpg)

Согласно легенде, основание христианства в Британии обычно приписывается Иосифу Аримафейскому и отмечается в аббатстве Гластонбери . [a] [22] Многие из ранних отцов церкви писали о присутствии христианства в Римской Британии , а Тертуллиан утверждал, что «те части Британии, в которые никогда не проникало римское оружие, стали подвластны Христу». [23] Святой Альбан , казненный в 209 году нашей эры, является первым христианским мучеником на Британских островах. По этой причине его почитают как британского первомученика . [24] Историк Генрих Циммер пишет, что «так же, как Британия была частью Римской империи, так и Британская церковь образовала (в четвертом веке) ветвь Католической церкви Запада; и в течение всего этого столетия, начиная с Арльского собора (316 г.), принимала участие во всех процессах, касающихся Церкви». [25]

После того, как римские войска покинули Британию , «отсутствие римского военного и государственного влияния и общий упадок римской имперской политической власти позволили Британии и окружающим островам развиваться отдельно от остального Запада. Новая культура возникла вокруг Ирландского моря среди кельтских народов , в основе которой лежало кельтское христианство . В результате возникла форма христианства, отличная от Рима во многих традициях и обычаях». [b] [28] [29]

Историк Чарльз Томас , в дополнение к кельтисту Генриху Циммеру, пишет, что различие между субримским и постримским островным христианством, также известным как кельтское христианство, начало проявляться около 475 г. н. э. [30] с кельтскими церквями , допускающими женатое духовенство, [31] соблюдающими Великий пост и Пасху по своему собственному календарю, [32] [33] и имеющими другую тонзуру ; более того, подобно Восточным православным и Восточным православным церквям, кельтские церкви действовали независимо от власти Папы, [34] в результате их изолированного развития на Британских островах. [35]

В так называемой григорианской миссии папа Григорий I отправил Августина Кентерберийского на Британские острова в 596 году нашей эры с целью евангелизации тамошних язычников (которые были в основном англосаксами ), [36] а также примирения кельтских церквей на Британских островах с Римским престолом . [37] В Кенте Августин убедил англосаксонского короля « Этельберта и его людей принять христианство». [38] Августин дважды «встречался на конференции с членами кельтского епископата, но между ними не было достигнуто никакого взаимопонимания». [39]

В конце концов, «Христианская церковь англосаксонского королевства Нортумбрия созвала Синод Уитби в 663/664 году, чтобы решить, следовать ли кельтским или римским обычаям». Эта встреча, на которой король Освиу принял окончательное решение, «привела к принятию римского обычая в других частях Англии и привела Английскую церковь к тесному контакту с Континентом». [40] В результате принятия римских обычаев Кельтская церковь отказалась от своей независимости, и с этого момента Церковь в Англии «больше не была чисто кельтской, а стала англо-римско-кельтской». [41] Теолог Кристофер Л. Уэббер пишет, что «хотя «римская форма христианства стала доминирующим влиянием в Британии, как и во всей Западной Европе, англиканское христианство продолжало иметь отличительные качества из-за своего кельтского наследия». [42] [43] [44]

Церковь в Англии оставалась единой с Римом до английского парламента, хотя Акт о супремати (1534) объявил короля Генриха VIII Верховным главой Церкви Англии , чтобы исполнить «английское желание быть независимым от континентальной Европы религиозно и политически». Поскольку изменение было в основном политическим, сделанным для того, чтобы позволить аннулировать брак Генриха VIII, [45] английская церковь при Генрихе VIII продолжала поддерживать католические доктрины и литургические празднования таинств, несмотря на свое отделение от Рима. За небольшим исключением, Генрих VIII не допускал никаких изменений в течение своей жизни. [46] Однако при короле Эдуарде VI (1547–1553) церковь в Англии впервые начала подвергаться тому, что известно как английская Реформация , в ходе которой она приобрела ряд характеристик, которые впоследствии были признаны составляющими ее отличительную «англиканскую» идентичность. [47]

С Елизаветинским соглашением 1559 года протестантская идентичность английской и ирландской церквей была подтверждена посредством парламентского законодательства, которое предписывало всем их членам быть верными и преданными английской короне. Елизаветинская церковь начала развивать особые религиозные традиции, ассимилируя часть теологии реформатских церквей с богослужениями в Книге общей молитвы (которая в значительной степени опиралась на обряд Сарум, родившийся в Англии), под руководством и организацией постоянного епископата. [48] С годами эти традиции сами по себе стали требовать приверженности и преданности. Елизаветинское соглашение остановило радикальные протестантские тенденции при Эдуарде VI, объединив более радикальные элементы молитвенника 1552 года с консервативным «католическим» молитвенником 1549 года в Книгу общей молитвы 1559 года . С тех пор протестантизм находился в «состоянии задержанного развития», несмотря на попытки различных групп, пытавшихся в 1560–1660 годах подтолкнуть Англиканскую церковь к более реформатскому богословию и управлению, оторвать ее от «идиосинкразической привязки к средневековому прошлому». [49]

Хотя два важных составных элемента того, что позже станет англиканством, присутствовали в 1559 году — Священное Писание, исторический епископат , Книга общей молитвы , учения Первых четырех Вселенских соборов как мерило соборности, учение Отцов Церкви и католических епископов и информированный разум — ни миряне, ни духовенство не воспринимали себя как англикан в начале правления Елизаветы I, поскольку такой идентичности не было. Термин via media также не появляется до 1627 года для описания церкви, которая отказывалась определенно идентифицировать себя как католическую или протестантскую, или как обе, «и решила в конце концов, что это добродетель, а не недостаток». [50]

Исторические исследования периода 1560–1660 гг., написанные до конца 1960-х гг., имели тенденцию проецировать преобладающую конформистскую духовность и доктрину 1660-х гг. на церковную ситуацию столетней давности, а также существовала тенденция принимать полемически бинарные разделения реальности, заявленные исследователями (такие как дихотомии протестантский-«папистский» или « лаудианский »-«пуританин») за чистую монету. С конца 1960-х гг. эти интерпретации подвергались критике. Исследования по этой теме, написанные за последние сорок пять лет, однако, не достигли консенсуса относительно того, как интерпретировать этот период в истории английской церкви. Степень, в которой одна или несколько позиций относительно доктрины и духовности существовали наряду с более известным и четко выраженным пуританским движением и партией Дарем-хаус, а также точная степень континентального кальвинизма среди английской элиты и среди рядовых прихожан с 1560-х по 1620-е гг. являются предметами текущих и продолжающихся дебатов. [с]

В 1662 году при короле Карле II была создана пересмотренная Книга общих молитв , которая была приемлема как для высших церковнослужителей, так и для некоторых пуритан и по сей день считается авторитетной. [51]

Поскольку англикане черпали свою идентичность как из парламентского законодательства, так и из церковной традиции, кризис идентичности мог возникнуть везде, где вступали в конфликт светские и религиозные лояльности — и такой кризис действительно произошел в 1776 году с Декларацией независимости Соединенных Штатов , большинство подписавших ее были, по крайней мере номинально, англиканами. [52] Для этих американских патриотов даже формы англиканских служб были под вопросом, поскольку обряды молитвенника утрени , вечерни и святого причастия включали особые молитвы за британскую королевскую семью. Следовательно, завершение Войны за независимость в конечном итоге привело к созданию двух новых англиканских церквей, Епископальной церкви в Соединенных Штатах в тех штатах, которые добились независимости; и в 1830-х годах Церковь Англии в Канаде стала независимой от Церкви Англии в тех североамериканских колониях, которые оставались под британским контролем и куда мигрировали многие церковнослужители-лоялисты. [53]

С неохотой в британском парламенте был принят закон (Закон о посвящении епископов за границей 1786 года), позволяющий посвящать епископов для американской церкви вне зависимости от британской короны (поскольку в бывших американских колониях никогда не было создано ни одной епархии). [53] Как в Соединенных Штатах, так и в Канаде новые англиканские церкви разработали новые модели самоуправления, коллективного принятия решений и самофинансирования; это соответствовало бы разделению религиозной и светской идентичности. [54]

В следующем столетии еще два фактора действовали, чтобы ускорить развитие отчетливой англиканской идентичности. С 1828 и 1829 годов диссентеры и католики могли быть избраны в Палату общин [55] , которая впоследствии перестала быть органом, набранным исключительно из устоявшихся церквей Шотландии, Англии и Ирландии; но которая, тем не менее, в течение следующих десяти лет занималась обширным реформированием законодательства, затрагивающего интересы английской и ирландской церквей; которые, согласно Актам об унии 1800 года , были воссозданы как Объединенная церковь Англии и Ирландии . Уместность этого законодательства яростно оспаривалась Оксфордским движением (трактарианцами), [56] которые в ответ разработали видение англиканства как религиозной традиции, вытекающей в конечном счете из экуменических соборов патристической церкви. Те внутри Церкви Англии, кто выступал против трактарианцев и их возрожденных ритуальных практик, внесли поток законопроектов в парламент, направленных на контроль инноваций в богослужении. [57] Это только обострило дилемму, что привело к постоянным судебным разбирательствам в светских и церковных судах.

В тот же период англиканские церкви активно занимались христианскими миссиями , что привело к созданию к концу века более девяноста колониальных епископств, [58] которые постепенно объединились в новые самоуправляемые церкви по канадским и американским образцам. Однако случай Джона Коленсо , епископа Наталя , восстановленного в 1865 году английским судебным комитетом Тайного совета над главами Церкви в Южной Африке, [59] наглядно продемонстрировал, что расширение епископства должно сопровождаться признанной англиканской экклезиологией церковной власти, отличной от светской власти.

В результате, по инициативе епископов Канады и Южной Африки, в 1867 году была созвана первая Ламбетская конференция ; [60] за которой последовали дальнейшие конференции в 1878 и 1888 годах, а затем с десятилетним интервалом. Различные документы и декларации последовательных Ламбетских конференций послужили основой для продолжающихся англиканских дебатов по идентичности, особенно в отношении возможности экуменического обсуждения с другими церквями. Это экуменическое стремление стало гораздо более вероятным, поскольку другие конфессиональные группы быстро последовали примеру Англиканского сообщества, основав свои собственные транснациональные альянсы: Альянс реформатских церквей , Экуменический методистский совет , Международный конгрегационалистский совет и Всемирный баптистский альянс .

Англиканство рассматривалось как средний путь, или via media , между двумя ветвями протестантизма, лютеранством и реформатским христианством. [16] В своем отрицании абсолютной парламентской власти, трактарианцы , особенно Джон Генри Ньюман , оглядывались на труды англиканских богословов 17-го века, находя в этих текстах идею английской церкви как via media между протестантской и католической традициями. [61] Эта точка зрения была связана — особенно в трудах Эдварда Бувери Пьюзи — с теорией англиканства как одной из трех « ветвей » (наряду с католической церковью и православными церквями), исторически возникших из общей традиции самых ранних вселенских соборов . Сам Ньюман впоследствии отверг свою теорию via media , как по сути историцистскую и статическую и, следовательно, неспособную вместить какое-либо динамическое развитие внутри церкви. [61] Тем не менее, стремление обосновать англиканскую идентичность в трудах богословов 17-го века и в верности традициям Отцов Церкви отражает продолжающуюся тему англиканской экклезиологии, в последнее время в трудах Генри Роберта Макэду . [62]

Трактарианская формулировка теории via media между протестантизмом и католицизмом была по сути партийной платформой и неприемлема для англикан за пределами Оксфордского движения . Однако эта теория via media была переработана в экклезиологических трудах Фредерика Денисона Мориса в более динамичной форме, которая стала широко влиятельной. И Морис, и Ньюман считали Церковь Англии своего времени крайне несовершенной в вере; но в то время как Ньюман оглядывался на далекое прошлое, когда свет веры мог казаться ярче, Морис с нетерпением ждал возможности более яркого откровения веры в будущем. Морис считал протестантские и католические течения в Церкви Англии противоположными, но взаимодополняющими, оба сохраняющими элементы истинной церкви, но неполными друг без друга; так что истинная католическая и евангелическая церковь могла возникнуть посредством союза противоположностей. [63]

Центральным для точки зрения Мориса была его вера в то, что коллективные элементы семьи, нации и церкви представляли собой божественный порядок структур, через которые Бог разворачивает свою непрерывную работу творения. Следовательно, для Мориса протестантская традиция сохранила элементы национального различия, которые были среди признаков истинной вселенской церкви, но которые были утеряны в современном католицизме в интернационализме централизованной папской власти. В грядущей вселенской церкви, которую предвидел Морис, национальные церкви будут поддерживать шесть признаков соборности: крещение, евхаристию, символы веры, Писание, епископское служение и фиксированную литургию (которая может принимать различные формы в соответствии с божественно предписанными различиями в национальных характеристиках). [61] Это видение становящейся вселенской церкви как конгрегации автономных национальных церквей оказалось весьма близким по духу в англиканских кругах; и шесть признаков Мориса были адаптированы для формирования Четырехугольника Чикаго-Ламбет 1888 года. [64]

В последние десятилетия 20-го века теория Мориса и различные течения англиканской мысли, которые произошли от нее, подверглись критике со стороны Стивена Сайкса , [65] который утверждает, что термины протестантский и католический , используемые в этих подходах, являются синтетическими конструкциями, обозначающими церковные идентичности, неприемлемые для тех, к кому применяются эти ярлыки. Следовательно, Католическая церковь не считает себя партией или течением в пределах вселенской церкви, а скорее идентифицирует себя как вселенскую церковь. Более того, Сайкс критикует предположение, подразумеваемое в теориях via media , что не существует отличительного корпуса англиканских доктрин, кроме доктрин вселенской церкви; обвиняя это в том, что это оправдание не предпринимать систематическую доктрину вообще. [66]

Напротив, Сайкс отмечает высокую степень общности в англиканских литургических формах и в доктринальных пониманиях, выраженных в этих литургиях. Он предполагает, что англиканскую идентичность можно скорее найти в общей последовательной модели предписывающих литургий, установленных и поддерживаемых каноническим правом , и воплощающих как исторический депозит формальных заявлений доктрины, так и обрамляющих регулярное чтение и провозглашение Священного Писания. [67] Сайкс, тем не менее, соглашается с теми наследниками Мориса, которые подчеркивают неполноту англиканства как положительную черту, и цитирует с условным одобрением слова Майкла Рэмси :

Ибо в то время как англиканская церковь оправдана своим местом в истории, поразительно сбалансированным свидетельством Евангелия и Церкви и здравым знанием, ее большее оправдание заключается в том, что она указывает через свою собственную историю на то, фрагментом чего она является. Ее верительные грамоты - ее незавершенность, с напряжением и мучениями ее души. Она неуклюжа и неопрятна, она сбивает с толку аккуратность и логику. Ибо она послана не для того, чтобы хвалить себя как «лучший тип христианства», но самой своей надломленностью, чтобы указать на вселенскую Церковь, в которой все умерли. [68]

Различие между реформатами и католиками, а также их согласованность являются предметом споров в англиканском сообществе. Оксфордское движение середины XIX века возродило и расширило доктринальные, литургические и пастырские практики, схожие с практиками римского католицизма. Это выходит за рамки церемонии высоких церковных служб и распространяется на еще более теологически значимую территорию, такую как сакраментальное богословие (см. англиканские таинства ). Хотя англокатолические практики, особенно литургические, стали более распространенными в традиции за последнее столетие, есть также места, где практики и верования более тесно перекликаются с евангельскими движениями 1730-х годов (см. Сиднейское англиканство ).

Для англикан высокой церкви доктрина не установлена магистериумом , не выведена из теологии одноименного основателя (например, кальвинизма ), и не суммирована в исповедании веры за пределами экуменических символов веры , таких как лютеранская Книга согласия . Для них самые ранние англиканские теологические документы - это молитвенники, которые они рассматривают как продукты глубоких теологических размышлений, компромисса и синтеза. Они подчеркивают Книгу общей молитвы как ключевое выражение англиканской доктрины. Принцип рассмотрения молитвенников как руководства по параметрам веры и практики называется латинским названием lex orandi, lex credendi («закон молитвы - это закон веры»).

В молитвенниках содержатся основы англиканской доктрины: Апостольский и Никейский символы веры, Афанасиевский символ веры (в настоящее время редко используемый), Священные Писания (через лекционарий), таинства, ежедневная молитва, катехизис и апостольская преемственность в контексте исторического трехчастного служения. Для некоторых низших церквей и евангельских англикан реформатские Тридцать девять статей XVI века составляют основу доктрины.

Тридцать девять статей сыграли значительную роль в англиканской доктрине и практике. После принятия канонов 1604 года все англиканское духовенство должно было официально подписаться под статьями. Однако сегодня статьи больше не являются обязательными, [69] но рассматриваются как исторический документ, сыгравший значительную роль в формировании англиканской идентичности. Степень, в которой каждая из статей оставалась влиятельной, варьируется.

Например, в отношении доктрины оправдания существует широкий спектр убеждений в англиканском сообществе, при этом некоторые англо-католики отстаивают веру с добрыми делами и таинствами. В то же время, однако, некоторые евангельские англикане приписывают реформатскому акценту sola fide («только вера») в своей доктрине оправдания (см. Сиднейское англиканство ). Другие англикане принимают нюансированный взгляд на оправдание, беря элементы из ранних отцов церкви , католицизма , протестантизма , либеральной теологии и латитудинарианской мысли.

Вероятно, наиболее влиятельной из первоначальных статей была Статья VI о «достаточности Писания», в которой говорится, что «Писание содержит все необходимое для спасения: так что все, что в нем не прочитано и не доказано из него, не может быть требуемо ни от кого, чтобы сие считалось догматом веры или считалось необходимым или необходимым для спасения». Эта статья с древнейших времен повлияла на англиканскую библейскую экзегезу и герменевтику .

Англикане ищут авторитет в своих «стандартных богословах» (см. ниже). Исторически самым влиятельным из них — помимо Кранмера — был священнослужитель и теолог XVI века Ричард Хукер , которого после 1660 года все чаще изображали как отца-основателя англиканства. Описание Хукером англиканского авторитета как исходящего в первую очередь из Священного Писания, информированного разумом (интеллектом и опытом Бога) и традицией (практиками и верованиями исторической церкви), повлияло на англиканскую самоидентификацию и доктринальное размышление, возможно, сильнее, чем любая другая формула. Аналогия «трехногого табурета» Писания , разума и традиции часто неправильно приписывается Хукеру. Скорее, описание Хукера представляет собой иерархию авторитета, в которой Писание является основополагающим, а разум и традиция — жизненно важными, но вторичными авторитетами.

Наконец, распространение англиканства на неанглийские культуры, растущее разнообразие молитвенников и растущий интерес к экуменическому диалогу привели к дальнейшему размышлению о параметрах англиканской идентичности. Многие англикане смотрят на Четырехугольник Чикаго-Ламбет 1888 года как на sine qua non общинной идентичности. [70] Короче говоря, четыре точки четырехугольника - это Священные Писания как содержащие все необходимое для спасения; Символы веры (в частности, Апостольский и Никейский Символы веры) как достаточное утверждение христианской веры; господствующие таинства Крещения и Святого Причастия ; и исторический епископат . [70]

В англиканской традиции «богословы» — это священнослужители Церкви Англии, чьи теологические труды считаются стандартами веры, доктрины, поклонения и духовности, и чье влияние в разной степени проникало в англиканское сообщество на протяжении многих лет. [71] Хотя не существует авторитетного списка этих англиканских богословов, есть некоторые, чьи имена, вероятно, можно найти в большинстве списков — те, кого поминают в меньшие праздники англиканских церквей, и те, чьи труды часто включаются в антологии . [72]

Корпус, созданный англиканскими богословами, разнообразен. Что их объединяет, так это приверженность вере, переданной Священным Писанием и Книгой общей молитвы , таким образом, рассматривая молитву и теологию в манере, родственной манере апостольских отцов . [73] В целом, англиканские богословы рассматривают via media англиканства не как компромисс, а как «позитивную позицию, свидетельствующую об универсальности Бога и Божьего царства, действующего через подверженную ошибкам, земную ecclesia Anglicana ». [74]

Эти теологи считают писание, интерпретируемое через традицию и разум, авторитетным в вопросах, касающихся спасения. Разум и традиция, действительно, присутствуют в писании и предполагаются им, тем самым подразумевая сотрудничество между Богом и человечеством, Богом и природой, а также между священным и мирским. Вера, таким образом, рассматривается как воплощенная , а авторитет — как рассеянный.

Среди ранних англиканских богословов XVI и XVII веков преобладают имена Томаса Кранмера , Джона Джуэла , Мэтью Паркера , Ричарда Хукера , Ланселота Эндрюса и Джереми Тейлора . Влияние труда Хукера «О законах церковной политики» невозможно переоценить. Опубликованный в 1593 году и позднее восьмитомный труд Хукера в первую очередь представляет собой трактат об отношениях церкви и государства, но в нем всесторонне рассматриваются вопросы библейского толкования , сотериологии , этики и освящения . На протяжении всей работы Хукер ясно дает понять, что теология включает в себя молитву и касается конечных вопросов, и что теология имеет отношение к социальной миссии церкви.

В XVII веке в англиканстве возникло два важных течения: кембриджский платонизм с его мистическим пониманием разума как «свечи Господней» и евангельское возрождение с его акцентом на личном опыте Святого Духа . Кембриджское платонистское движение превратилось в школу, называемую латитюдинарианством , которая подчеркивала разум как барометр различения и занимала позицию безразличия к доктринальным и экклезиологическим различиям.

Евангельское возрождение, на которое оказали влияние такие деятели, как Джон Уэсли и Чарльз Симеон , вновь подчеркнуло важность оправдания через веру и, как следствие, важность личного обращения. Некоторые из этого движения, такие как Уэсли и Джордж Уайтфилд , принесли послание в Соединенные Штаты, повлияв на Первое Великое Пробуждение и создав англо-американское движение под названием Методизм , которое в конечном итоге структурно отделилось от англиканских церквей после Американской революции.

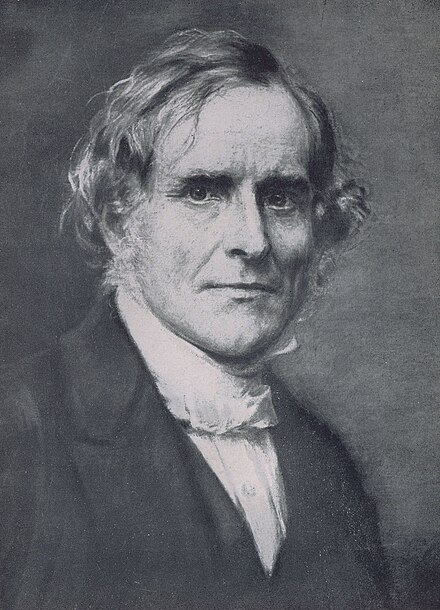

К 19 веку вновь возник интерес к дореформационной английской религиозной мысли и практике. Такие теологи, как Джон Кебл , Эдвард Бувери Пьюзи и Джон Генри Ньюман, оказали широкое влияние в области полемики, гомилетики, а также теологических и религиозных работ, не в последнюю очередь потому, что они в значительной степени отвергли старую традицию высокой церкви и заменили ее динамичным обращением к античности, которая выходила за рамки реформаторов и англиканских формулировок. [75] Их работа во многом связана с развитием Оксфордского движения , которое стремилось восстановить католическую идентичность и практику в англиканстве. [76]

В отличие от этого движения, духовенство, такое как епископ Ливерпуля, Дж. К. Райл , стремилось поддерживать отчетливо реформаторскую идентичность Церкви Англии. Он не был слугой статус-кво, но выступал за живую религию, которая подчеркивала благодать, святую и благотворительную жизнь и простое использование Книги общих молитв 1662 года (интерпретируемой в партийном евангельском ключе) [d] без дополнительных ритуалов. Фредерик Денисон Морис , посредством таких работ, как Царство Христа , сыграл ключевую роль в инаугурации другого движения, христианского социализма . В этом Морис преобразовал акцент Хукера на воплощенной природе англиканской духовности в императив социальной справедливости.

В 19 веке англиканская библейская наука начала приобретать особый характер, представленный так называемым «Кембриджским триумвиратом» Джозефа Лайтфута , Ф. Дж. А. Хорта и Брук Фосс Уэсткотт . [77] Их ориентация лучше всего подытожена замечанием Уэсткотта о том, что «Жизнь, которой является Христос и которую Христос сообщает, жизнь, которая наполняет все наше существо, когда мы осознаем ее способности, есть активное общение с Богом». [78] [79]

Начало 20-го века отмечено Чарльзом Гором , с его акцентом на естественном откровении , и Уильямом Темплом , сосредоточенным на христианстве и обществе, в то время как из-за пределов Англии были предложены Роберт Лейтон , архиепископ Глазго, и несколько священнослужителей из Соединенных Штатов, такие как Уильям Порчер Дюбоз , Джон Генри Хобарт (1775–1830, епископ Нью-Йорка 1816–30), Уильям Мид , Филлипс Брукс и Чарльз Брент . [80]

Церковничество можно определить как проявление теологии в сферах литургии, благочестия и, в некоторой степени, духовности. Разнообразие англикан в этом отношении, как правило, отражает разнообразие в реформаторской и католической идентичности традиции. Различные личности, группы, приходы, епархии и провинции могут более тесно идентифицировать себя с одним или другим, или с некоторой смесью двух.

The range of Anglican belief and practice became particularly divisive during the 19th century, when some clergy were disciplined and even imprisoned on charges of introducing illegal ritual while, at the same time, others were criticised for engaging in public worship services with ministers of Reformed churches. Resistance to the growing acceptance and restoration of traditional Catholic ceremonial by the mainstream of Anglicanism ultimately led to the formation of small breakaway churches such as the Free Church of England in England (1844) and the Reformed Episcopal Church in North America (1873).[81][82]

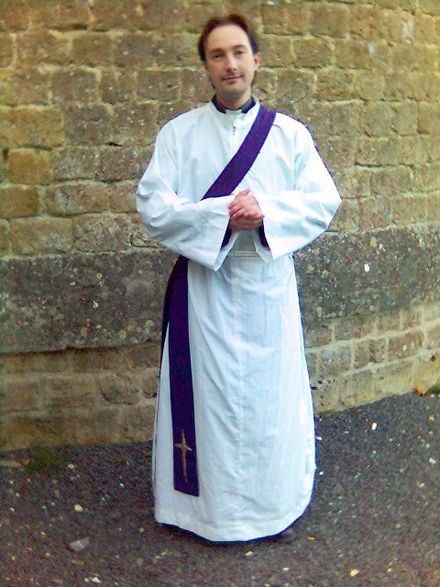

Anglo-Catholic (and some broad-church) Anglicans celebrate public liturgy in ways that understand worship to be something very special and of utmost importance. Vestments are worn by the clergy, sung settings are often used, and incense may be used. Nowadays, in most Anglican churches, the Eucharist is celebrated in a manner similar to the usage of Roman Catholics and some Lutherans, though, in many churches, more traditional, "pre–Vatican II" models of worship are common (e.g., an "eastward orientation" at the altar). Whilst many Anglo-Catholics derive much of their liturgical practice from that of the pre-Reformation English church, others more closely follow traditional Roman Catholic practices.

The Eucharist may sometimes be celebrated in the form known as High Mass, with a priest, deacon and subdeacon (usually actually a layman) dressed in traditional vestments, with incense and sanctus bells and prayers adapted from the Roman Missal or other sources by the celebrant. Such churches may also have forms of eucharistic adoration such as Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament. In terms of personal piety, some Anglicans may recite the Rosary and Angelus, be involved in a devotional society dedicated to "Our Lady" (the Blessed Virgin Mary) and seek the intercession of the saints.

In recent decades, the prayer books of several provinces have, out of deference to a greater agreement with Eastern Conciliarism (and a perceived greater respect accorded Anglicanism by Eastern Orthodoxy than by Roman Catholicism), instituted a number of historically Eastern and Oriental Orthodox elements in their liturgies, including introduction of the Trisagion and deletion of the filioque clause from the Nicene Creed.

For their part, those evangelical (and some broad-church) Anglicans who emphasise the more Protestant aspects of the Church stress the Reformation theme of salvation by grace through faith. They emphasise the two dominical sacraments of Baptism and Eucharist, viewing the other five as "lesser rites". Some evangelical Anglicans may even tend to take the inerrancy of scripture literally, adopting the view of Article VI that it contains all things necessary to salvation in an explicit sense. Worship in churches influenced by these principles tends to be significantly less elaborate, with greater emphasis on the Liturgy of the Word (the reading of the scriptures, the sermon, and the intercessory prayers).

The Order for Holy Communion may be celebrated bi-weekly or monthly (in preference to the daily offices), by priests attired in choir habit, or more regular clothes, rather than Eucharistic vestments. Ceremony may be in keeping with their view of the provisions of the 17th-century Puritans – being a Reformed interpretation of the Ornaments Rubric – no candles, no incense, no bells, and a minimum of manual actions by the presiding celebrant (such as touching the elements at the Words of Institution).

In the early 21st century, there has been a growth of charismatic worship among Anglicans. Both Anglo-Catholics and evangelicals have been affected by this movement such that it is not uncommon to find typically charismatic postures, music, and other themes evident during the services of otherwise Anglo-Catholic or evangelical parishes.

The spectrum of Anglican beliefs and practice is too large to be fit into these labels. Many Anglicans locate themselves somewhere in the spectrum of the broad-church tradition and consider themselves an amalgam of evangelical and Catholic. Such Anglicans stress that Anglicanism is the via media (middle way) between the two major strains of Western Christianity and that Anglicanism is like a "bridge" between the two strains.

In accord with its prevailing self-identity as a via media or "middle path" of Western Christianity, Anglican sacramental theology expresses elements in keeping with its status as being both a church in the Catholic tradition as well as a Reformed church. With respect to sacramental theology, the Catholic heritage is perhaps most strongly asserted in the importance Anglicanism places on the sacraments as a means of grace, sanctification, and salvation, as expressed in the church's liturgy and doctrine.

Of the seven sacraments, all Anglicans recognise Baptism and the Eucharist as being directly instituted by Christ. The other five – Confession/Absolution, Matrimony, Confirmation, Holy Orders (also called Ordination), and Anointing of the Sick (also called Unction) – are regarded variously as full sacraments by Anglo-Catholics and many high church and some broad-church Anglicans, but merely as "sacramental rites" by other broad-church and low-church Anglicans, especially evangelicals associated with Reform UK and the Diocese of Sydney.

Anglican eucharistic theology is divergent in practice, reflecting the essential comprehensiveness of the tradition. A few low-church Anglicans take a strictly memorialist (Zwinglian) view of the sacrament. In other words, they see Holy Communion as a memorial to Christ's suffering, and participation in the Eucharist as both a re-enactment of the Last Supper and a foreshadowing of the heavenly banquet – the fulfilment of the eucharistic promise.

Other low-church Anglicans believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist but deny that the presence of Christ is carnal or is necessarily localised in the bread and wine. Despite explicit criticism in the Thirty-Nine Articles, many high-church or Anglo-Catholic Anglicans hold, more or less, the Catholic view of the real presence as expressed in the doctrine of transubstantiation, seeing the Eucharist as a liturgical representation of Christ's atoning sacrifice with the elements actually transformed into Christ's body and blood.

The majority of Anglicans, however, have in common a belief in the real presence, defined in one way or another. To that extent, they are in the company of the continental reformer Martin Luther and Calvin rather than Ulrich Zwingli. The Catechism of the American BCP of 1976 repeats the standard Anglican view ("The outward and visible sign in the Eucharist is the bread and wine"..."The inward and spiritual grace in the Holy Communion is the Body and Blood of Christ given to his people, and received by faith") without further definition. It should be remembered that Anglicanism has no official doctrine on this matter, believing it is wiser to leave the Presence a mystery. The faithful can believe privately whatever explanation they favour, be it transubstantiation, consubstantiation, receptionism, or virtualism (the two[clarification needed] most congenial to Anglicans for centuries until the Oxford Movement), each of which espouses belief in the real presence in one way or another, or memorialism, which has never been an option with Anglicans.

A famous Anglican aphorism regarding Christ's presence in the sacrament, commonly misattributed to Queen Elizabeth I, is first found in print in a poem by John Donne:[83]

He was the word that spake it,

He took the bread and brake it:

And what that word did make it,

I do believe and take it.[84]

An Anglican position on the eucharistic sacrifice ("Sacrifice of the Mass") was expressed in the response Saepius officio of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York to Pope Leo XIII's papal encyclical Apostolicae curae: viz. that the Prayer Book contained a strong sacrificial theology. Later revisions of the Prayer Book influenced by the Scottish Canon of 1764 first adopted by the Protestant Episcopal Church in 1789 made this assertion quite evident: "we do make and celebrate before thy Divine Majesty with these thy holy gifts, which we now offer unto thee, the memorial thy Son has commanded us to make", which is repeated in the 1929 English BCP and included in such words or others such as "present" or "show forth" in subsequent revisions.

Anglican and Roman Catholic representatives declared that they had "substantial agreement on the doctrine of the Eucharist" in the Windsor Statement on Eucharistic Doctrine by the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Consultation (1971)[85] and the Elucidation of the ARCIC Windsor Statement (1979). The final response (1991) to these documents by the Vatican made it plain that it did not consider the degree of agreement reached to be satisfactory.

In Anglicanism there is a distinction between liturgy, which is the formal public and communal worship of the church, and personal prayer and devotion, which may be public or private. Liturgy is regulated by the prayer books and consists of the Eucharist (some call it Holy Communion or Mass), the other six sacraments, and the daily offices such as Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer.

The Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is the foundational prayer book of Anglicanism. The original book of 1549 (revised in 1552) was one of the instruments of the English Reformation, replacing the various "uses" or rites in Latin that had been used in different parts of the country with a single compact volume in the language of the people, so that "now from henceforth all the Realm shall have but one use". Suppressed under Queen Mary I, it was revised in 1559, and then again in 1662, after the Restoration of Charles II. This version was made mandatory in England and Wales by the Act of Uniformity and was in standard use until the mid-20th century.

With British colonial expansion from the 17th century onwards, Anglican churches were planted around the globe. These churches at first used and then revised the Book of Common Prayer until they, like their parent church, produced prayer books which took into account the developments in liturgical study and practice in the 19th and 20th centuries, which come under the general heading of the Liturgical Movement.

Anglican worship services are open to all visitors. Anglican worship originates principally in the reforms of Thomas Cranmer, who aimed to create a set order of service like that of the pre-Reformation church but less complex in its seasonal variety and said in English rather than Latin. This use of a set order of service is not unlike the Catholic tradition. Traditionally, the pattern was that laid out in the Book of Common Prayer. Although many Anglican churches now use a wide range of modern service books written in the local language, the structures of the Book of Common Prayer are largely retained. Churches which call themselves Anglican will have identified themselves so because they use some form or variant of the Book of Common Prayer in the shaping of their worship.

Anglican worship, however, is as diverse as Anglican theology. A contemporary "low church" service may differ little from the worship of many mainstream non-Anglican Protestant churches. The service is constructed around a sermon focused on Biblical exposition and opened with one or more Bible readings and closed by a series of prayers (both set and extemporised) and hymns or songs. A "high church" or Anglo-Catholic service, by contrast, is usually a more formal liturgy celebrated by clergy in distinctive vestments and may be almost indistinguishable from a Roman Catholic service, often resembling the "pre–Vatican II" Tridentine rite.

Between these extremes are a variety of styles of worship, often involving a robed choir and the use of the organ to accompany the singing and to provide music before and after the service. Anglican churches tend to have pews or chairs, and it is usual for the congregation to kneel for some prayers but to stand for hymns and other parts of the service such as the Gloria, Collect, Gospel reading, Creed and either the Preface or all of the Eucharistic Prayer. Anglicans may genuflect or cross themselves in the same way as Roman Catholics.

Other more traditional Anglicans tend to follow the 1662 Book of Common Prayer and retain the use of the King James Bible. This is typical in many Anglican cathedrals and particularly in royal peculiars such as the Savoy Chapel and the Queen's Chapel. These Anglican church services include classical music instead of songs, hymns from the New English Hymnal (usually excluding modern hymns such as "Lord of the Dance"), and are generally non-evangelical and formal in practice.

Until the mid-20th century the main Sunday service was typically Morning Prayer, but the Eucharist has once again become the standard form of Sunday worship in most Anglican churches; this again is similar to Roman Catholic practice. Other common Sunday services include an early morning Eucharist without music, an abbreviated Eucharist following a service of morning prayer, and a service of Evening Prayer, often called "Evensong" when sung, usually celebrated between 3:00 and 6:00 pm. The late-evening service of Compline was revived in parish use in the early 20th century. Many Anglican churches will also have daily morning and evening prayer, and some have midweek or even daily celebration of the Eucharist.

An Anglican service (whether or not a Eucharist) will include readings from the Bible that are generally taken from a standardised lectionary, which provides for much of the Bible (and some passages from the Apocrypha) to be read out loud in the church over a cycle of one, two, or three years (depending on which eucharistic and office lectionaries are used, respectively). The sermon (or homily) is typically about ten to twenty minutes in length, often comparably short to sermons in evangelical churches. Even in the most informal Anglican services, it is common for set prayers such as the weekly Collect to be read. There are also set forms for intercessory prayer, though this is now more often extemporaneous. In high and Anglo-Catholic churches there are generally prayers for the dead.

Although Anglican public worship is usually ordered according to the canonically approved services, in practice many Anglican churches use forms of service outside these norms. Liberal churches may use freely structured or experimental forms of worship, including patterns borrowed from ecumenical traditions such as those of the Taizé Community or the Iona Community.

Anglo-Catholic parishes might use the modern Roman Catholic liturgy of the Mass or more traditional forms, such as the Tridentine Mass (which is translated into English in the English Missal), the Anglican Missal, or, less commonly, the Sarum Rite. Catholic devotions such as the Rosary, Angelus, and Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament are also common among Anglo-Catholics.

Only baptised persons are eligible to receive communion,[86] although in many churches communion is restricted to those who have not only been baptised but also confirmed. In many Anglican provinces, however, all baptised Christians are now often invited to receive communion and some dioceses have regularised a system for admitting baptised young people to communion before they are confirmed.

The discipline of fasting before communion is practised by some Anglicans. Most Anglican priests require the presence of at least one other person for the celebration of the Eucharist (referring back to Christ's statement in Matthew 18:20, "When two or more are gathered in my name, I will be in the midst of them."), though some Anglo-Catholic priests (like Roman Catholic priests) may say private Masses. As in the Roman Catholic Church, it is a canonical requirement to use fermented wine for communion.

Unlike in Roman Catholicism, the consecrated bread and wine are normally offered to the congregation at a eucharistic service ("communion in both kinds"). This practice is becoming more frequent in the Roman Catholic Church as well, especially through the Neocatechumenal Way. In some churches, the sacrament is reserved in a tabernacle or aumbry with a lighted candle or lamp nearby. In Anglican churches, only a priest or a bishop may be the celebrant at the Eucharist.

All Anglican prayer books contain offices for Morning Prayer (Matins) and Evening Prayer (Evensong). In the original Book of Common Prayer, these were derived from combinations of the ancient monastic offices of Matins and Lauds; and Vespers and Compline, respectively. The prayer offices have an important place in Anglican history.

Prior to the Catholic revival of the 19th century, which eventually restored the Eucharist as the principal Sunday liturgy, and especially during the 18th century, a morning service combining Matins, the Litany, and ante-Communion comprised the usual expression of common worship, while Matins and Evensong were sung daily in cathedrals and some collegiate chapels. This nurtured a tradition of distinctive Anglican chant applied to the canticles and psalms used at the offices (although plainsong is often used as well).

In some official and many unofficial Anglican service books, these offices are supplemented by other offices such as the Little Hours of Prime and prayer during the day such as (Terce, Sext, None, and Compline). Some Anglican monastic communities have a Daily Office based on that of the Book of Common Prayer but with additional antiphons and canticles, etc., for specific days of the week, specific psalms, etc. See, for example, Order of the Holy Cross[87] and Order of St Helena, editors, A Monastic Breviary (Wilton, Conn.: Morehouse-Barlow, 1976). The All Saints Sisters of the Poor,[88] with convents in Catonsville, Maryland, and elsewhere, use an elaborated version of the Anglican Daily Office. The Society of St. Francis publishes Celebrating Common Prayer, which has become especially popular for use among Anglicans.

In England, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and some other Anglican provinces, the modern prayer books contain four offices:

In addition, most prayer books include a section of prayers and devotions for family use. In the US, these offices are further supplemented by an "Order of Worship for the Evening", a prelude to or an abbreviated form of Evensong, partly derived from Orthodox prayers. In the United Kingdom, the publication of Daily Prayer, the third volume of Common Worship, was published in 2005. It retains the services for Morning and Evening Prayer and Compline and includes a section entitled "Prayer during the Day". A New Zealand Prayer Book of 1989 provides different outlines for Matins and Evensong on each day of the week, as well as "Midday Prayer", "Night Prayer" and "Family Prayer".

Some Anglicans who pray the office on daily basis use the present Divine Office of the Roman Catholic Church. In many cities, especially in England, Anglican and Roman Catholic priests and lay people often meet several times a week to pray the office in common. A small but enthusiastic minority use the Anglican Breviary, or other translations and adaptations of the pre–Vatican II Roman Rite and Sarum Rite, along with supplemental material from cognate western sources, to provide such things as a common of Octaves, a common of Holy Women, and other additional material. Others may privately use idiosyncratic forms borrowed from a wide range of Christian traditions.

In the late medieval period, many English cathedrals and monasteries had established small choirs of trained lay clerks and boy choristers to perform polyphonic settings of the Mass in their Lady chapels. Although these "Lady Masses" were discontinued at the Reformation, the associated musical tradition was maintained in the Elizabethan Settlement through the establishment of choral foundations for daily singing of the Divine Office by expanded choirs of men and boys. This resulted from an explicit addition by Elizabeth herself to the injunctions accompanying the 1559 Book of Common Prayer (that had itself made no mention of choral worship) by which existing choral foundations and choir schools were instructed to be continued, and their endowments secured. Consequently, some thirty-four cathedrals, collegiate churches, and royal chapels maintained paid establishments of lay singing men and choristers in the late 16th century.[89]

All save four of these have – with interruptions during the Commonwealth and the COVID-19 pandemic – continued daily choral prayer and praise to this day. In the Offices of Matins and Evensong in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, these choral establishments are specified as "Quires and Places where they sing".

For nearly three centuries, this round of daily professional choral worship represented a tradition entirely distinct from that embodied in the intoning of Parish Clerks, and the singing of "west gallery choirs" which commonly accompanied weekly worship in English parish churches. In 1841, the rebuilt Leeds Parish Church established a surpliced choir to accompany parish services, drawing explicitly on the musical traditions of the ancient choral foundations. Over the next century, the Leeds example proved immensely popular and influential for choirs in cathedrals, parish churches, and schools throughout the Anglican communion.[90] More or less extensively adapted, this choral tradition also became the direct inspiration for robed choirs leading congregational worship in a wide range of Christian denominations.

In 1719, the cathedral choirs of Gloucester, Hereford, and Worcester combined to establish the annual Three Choirs Festival, the precursor for the multitude of summer music festivals since. By the 20th century, the choral tradition had become for many the most accessible face of worldwide Anglicanism – especially as promoted through the regular broadcasting of choral evensong by the BBC; and also in the annual televising of the festival of Nine Lessons and Carols from King's College, Cambridge. Composers closely concerned with this tradition include Edward Elgar, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst, Charles Villiers Stanford, and Benjamin Britten. A number of important 20th-century works by non-Anglican composers were originally commissioned for the Anglican choral tradition – for example, the Chichester Psalms of Leonard Bernstein and the Nunc dimittis of Arvo Pärt.

Contrary to popular misconception, the British monarch is not the constitutional "head" of the Church of England but is, in law, the church's "supreme governor", nor does the monarch have any role in provinces outside England. The role of the crown in the Church of England is practically limited to the appointment of bishops, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, and even this role is limited, as the church presents the government with a short list of candidates from which to choose. This process is accomplished through collaboration with and consent of ecclesial representatives (see Ecclesiastical Commissioners). Although the monarch has no constitutional role in Anglican churches in other parts of the world, the prayer books of several countries where the monarch is head of state contain prayers for him or her as sovereign.

A characteristic of Anglicanism is that it has no international juridical authority. All forty-two provinces of the Anglican Communion are autonomous, each with their own primate and governing structure. These provinces may take the form of national churches (such as in Canada, Uganda or Japan) or a collection of nations (such as the West Indies, Central Africa or South Asia), or geographical regions (such as Vanuatu and Solomon Islands) etc. Within these provinces there may exist subdivisions, called ecclesiastical provinces, under the jurisdiction of a metropolitan archbishop.

All provinces of the Anglican Communion consist of dioceses, each under the jurisdiction of a bishop. In the Anglican tradition, bishops must be consecrated according to the strictures of apostolic succession, which Anglicans consider one of the marks of catholicity. Apart from bishops, there are two other orders of ordained ministry: deacon and priest.

No requirement is made for clerical celibacy, though many Anglo-Catholic priests have traditionally been bachelors. Because of innovations that occurred at various points after the latter half of the 20th century, women may be ordained as deacons in almost all provinces, as priests in most and as bishops in many. Anglican religious orders and communities, suppressed in England during the Reformation, have re-emerged, especially since the mid-19th century, and now have an international presence and influence.

Government in the Anglican Communion is synodical, consisting of three houses of laity (usually elected parish representatives), clergy and bishops. National, provincial and diocesan synods maintain different scopes of authority, depending on their canons and constitutions. Anglicanism is not congregational in its polity: it is the diocese, not the parish church, which is the smallest unit of authority in the church. (See Episcopal polity).

The Archbishop of Canterbury has a precedence of honour over the other primates of the Anglican Communion, and for a province to be considered a part of the communion means specifically to be in full communion with the see of Canterbury – though this principle is currently subject to considerable debate, especially among those in the so-called Global South, including American Anglicans.[91] The archbishop is, therefore, recognised as primus inter pares ("first amongst equals"), even though he does not exercise any direct authority in any province outside England, of which he is chief primate.[92][93] Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 to 2012, was the first archbishop appointed from outside the Church of England since the Reformation: he was formerly the Archbishop of Wales.

As "spiritual head" of the communion, the Archbishop of Canterbury maintains a certain moral authority and has the right to determine which churches will be in communion with his see. He hosts and chairs the Lambeth Conferences of Anglican Communion bishops and decides who will be invited to them. He also hosts and chairs the Anglican Communion Primates' Meeting and is responsible for the invitations to it. He acts as president of the secretariat of the Anglican Communion Office and its deliberative body, the Anglican Consultative Council.

The Anglican Communion has no international juridical organisation. All international bodies are consultative and collaborative, and their resolutions are not legally binding on the autonomous provinces of the communion. There are three international bodies of note.

Like the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox churches, the Anglican Communion maintains the threefold ministry of deacons, presbyters (usually called "priests"), and bishops.

Bishops, who possess the fullness of Christian priesthood, are the successors of the apostles. Primates, archbishops, and metropolitans are all bishops and members of the historical episcopate who derive their authority through apostolic succession – an unbroken line of bishops that can be traced back to the 12 apostles of Jesus.

Bishops are assisted by priests and deacons. Most ordained ministers in the Anglican Communion are priests, who usually work in parishes within a diocese. Priests are in charge of the spiritual life of parishes and are usually called the rector or vicar. A curate (or, more correctly, an "assistant curate") is a priest or deacon who assists the parish priest. Non-parochial priests may earn their living by any vocation, although employment by educational institutions or charitable organisations is most common. Priests also serve as chaplains of hospitals, schools, prisons, and in the armed forces.

An archdeacon is a priest or deacon responsible for administration of an archdeaconry, which is often the name given to the principal subdivisions of a diocese. An archdeacon represents the diocesan bishop in his or her archdeaconry. In the Church of England, the position of archdeacon can only be held by someone in priestly orders who has been ordained for at least six years. In some other parts of the Anglican Communion, the position can also be held by deacons. In parts of the Anglican Communion where women cannot be ordained as priests or bishops but can be ordained as deacons, the position of archdeacon is effectively the most senior office to which an ordained woman can be appointed.

A dean is a priest who is the principal cleric of a cathedral or other collegiate church and the head of the chapter of canons. If the cathedral or collegiate church has its own parish, the dean is usually also rector of the parish. However, in the Church of Ireland, the roles are often separated, and most cathedrals in the Church of England do not have associated parishes. In the Church in Wales, however, most cathedrals are parish churches and their deans are now also vicars of their parishes.

The Anglican Communion recognises Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox ordinations as valid. Outside the Anglican Communion, Anglican ordinations (at least of male priests) are recognised by the Old Catholic Church, Porvoo Communion Lutherans, and various Independent Catholic churches.

In Anglican churches, deacons often work directly in ministry to the marginalised inside and outside the church: the poor, the sick, the hungry, the imprisoned. Unlike Orthodox and most Roman Catholic deacons who may be married only before ordination, deacons are permitted to marry freely both before and after ordination, as are priests. Most deacons are preparing for priesthood and usually only remain as deacons for about a year before being ordained priests. However, there are some deacons who remain so.

Many provinces of the Anglican Communion ordain both men and women as deacons. Many of those provinces that ordain women to the priesthood previously allowed them to be ordained only to the diaconate. The effect of this was the creation of a large and overwhelmingly female diaconate for a time, as most men proceeded to be ordained priest after a short time as a deacon.

Deacons, in some dioceses, can be granted licences to solemnise matrimony, usually under the instruction of their parish priest and bishop. They sometimes officiate at Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament in churches which have this service. Deacons are not permitted to preside at the Eucharist (but can lead worship with the distribution of already consecrated communion where this is permitted),[95] absolve sins, or pronounce a blessing.[96] It is the prohibition against deacons pronouncing blessings that leads some to believe that deacons cannot solemnise matrimony.

All baptised members of the church are called Christian faithful, truly equal in dignity and in the work to build the church. Some non-ordained people also have a formal public ministry, often on a full-time and long-term basis – such as lay readers (also known as readers), churchwardens, vergers, and sextons. Other lay positions include acolytes (male or female, often children), lay eucharistic ministers (also known as chalice bearers), and lay eucharistic visitors (who deliver consecrated bread and wine to "shut-ins" or members of the parish who are unable to leave home or hospital to attend the Eucharist). Lay people also serve on the parish altar guild (preparing the altar and caring for its candles, linens, flowers, etc.), in the choir and as cantors, as ushers and greeters, and on the church council (called the "vestry" in some countries), which is the governing body of a parish.

A small yet influential aspect of Anglicanism is its religious orders and communities. Shortly after the beginning of the Catholic Revival in the Church of England, there was a renewal of interest in re-establishing religious and monastic orders and communities. One of Henry VIII's earliest acts was their dissolution and seizure of their assets. In 1841, Marian Rebecca Hughes became the first woman to take the vows of religion in communion with the Province of Canterbury since the Reformation.

In 1848, Priscilla Lydia Sellon became the superior of the Society of the Most Holy Trinity at Devonport, Plymouth, the first organised religious order. Sellon is called "the restorer, after three centuries, of the religious life in the Church of England".[97] For the next one hundred years, religious orders for both men and women proliferated throughout the world, becoming a numerically small but disproportionately influential feature of global Anglicanism.

Anglican religious life at one time boasted hundreds of orders and communities, and thousands of religious. An important aspect of Anglican religious life is that most communities of both men and women lived their lives consecrated to God under the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, or, in Benedictine communities, Stability, Conversion of Life, and Obedience, by practising a mixed life of reciting the full eight services of the Breviary in choir, along with a daily Eucharist, plus service to the poor. The mixed life, combining aspects of the contemplative orders and the active orders, remains to this day a hallmark of Anglican religious life. Another distinctive feature of Anglican religious life is the existence of some mixed-gender communities.

Since the 1960s, there has been a sharp decline in the number of professed religious in most parts of the Anglican Communion, especially in North America, Europe, and Australia. Many once large and international communities have been reduced to a single convent or monastery with memberships of elderly men or women. In the last few decades of the 20th century, novices have for most communities been few and far between. Some orders and communities have already become extinct. There are, however, still thousands of Anglican religious working today in approximately 200 communities around the world, and religious life in many parts of the Communion – especially in developing nations – flourishes.

The most significant growth has been in the Melanesian countries of the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and Papua New Guinea. The Melanesian Brotherhood, founded at Tabalia, Guadalcanal, in 1925 by Ini Kopuria, is now the largest Anglican Community in the world, with over 450 brothers in the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, and the United Kingdom. The Sisters of the Church, started by Mother Emily Ayckbowm in England in 1870, has more sisters in the Solomons than all their other communities. The Community of the Sisters of Melanesia, started in 1980 by Sister Nesta Tiboe, is a growing community of women in the Solomon Islands.

The Society of Saint Francis, founded as a union of various Franciscan orders in the 1920s, has experienced great growth in the Solomon Islands. Other communities of religious have been started by Anglicans in Papua New Guinea and in Vanuatu. Most Melanesian Anglican religious are in their early to mid-20s. Vows may be temporary, and it is generally assumed that brothers, at least, will leave and marry in due course, making the average age 40 to 50 years younger than their brothers and sisters in other countries. Growth of religious orders, especially for women, is marked in certain parts of Africa.

Anglicanism represents the third largest Christian communion in the world, after the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church.[5] The number of Anglicans in the world is over 85 million as of 2011[update].[98] The 11 provinces in Africa saw growth in the last two decades. They now include 36.7 million members, more Anglicans than there are in England. England remains the largest single Anglican province, with 26 million members. In most industrialised countries, church attendance has decreased since the 19th century. Anglicanism's presence in the rest of the world is due to large-scale emigration, the establishment of expatriate communities, or the work of missionaries.

The Church of England has been a church of missionaries since the 17th century, when the Church first left English shores with colonists who founded what would become the United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa, and established Anglican churches. For example, an Anglican chaplain, Robert Wolfall, with Martin Frobisher's Arctic expedition, celebrated the Eucharist in 1578 in Frobisher Bay.

The first Anglican church in the Americas was built at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. By the 18th century, missionaries worked to establish Anglican churches in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The great Church of England missionary societies were founded; for example, the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) in 1698, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) in 1701, and the Church Mission Society (CMS) in 1799.

In the 19th century, social-oriented evangelism with societies were founded and developed, including the Church Pastoral Aid Society (CPAS) in 1836, Mission to Seafarers in 1856, Girls' Friendly Society (GFS) in 1875, Mothers' Union in 1876, and Church Army in 1882, all carrying out a personal form of evangelism.

In the 20th century, the Church of England developed new forms of evangelism, including the Alpha course in 1990, which was developed and propagated from Holy Trinity Brompton Church in London.

In the 21st century, there has been renewed effort to reach children and youth. Fresh expressions is a Church of England missionary initiative to youth begun in 2005, and has ministries at a skate park[99] through the efforts of St George's Church, Benfleet, Essex, the Diocese of Chelmsford, or youth groups with evocative names, like the C.L.A.W (Christ Little Angels – Whatever!) youth group at Coventry Cathedral. For those who prefer not to actually visit a brick and mortar church, there are Internet ministries, such as the Diocese of Oxford's online Anglican i-Church, which was founded on the web in 2005.

Anglican interest in ecumenical dialogue can be traced back to the time of the Reformation and dialogues with both Orthodox and Lutheran churches in the 16th century. In the 19th century, with the rise of the Oxford Movement, there arose greater concern for reunion of the churches of "Catholic confession". This desire to work towards full communion with other denominations led to the development of the Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral, approved by the third Lambeth Conference of 1888. The four points (the sufficiency of scripture, the historic creeds, the two dominical sacraments, and the historic episcopate) were proposed as a basis for discussion, although they have frequently been taken as a non-negotiable bottom-line for any form of reunion.

.jpg/440px-High_Altar,_Church_of_the_Good_Shepherd_(Rosemont,_Pennsylvania).jpg)

Anglicanism in general has always sought a balance between the emphases of Catholicism and Protestantism, while tolerating a range of expressions of evangelicalism and ceremony. Clergy and laity from all Anglican churchmanship traditions have been active in the formation of the Continuing movement.

While there are high church, broad-church and low-church Continuing Anglicans, many Continuing churches are Anglo-Catholic with highly ceremonial liturgical practices. Others belong to a more evangelical or low-church tradition and tend to support the Thirty-nine Articles and simpler worship services. Morning Prayer, for instance, is often used instead of the Holy Eucharist for Sunday worship services, although this is not necessarily true of all low-church parishes.

Most Continuing churches in the United States reject the 1979 revision of the Book of Common Prayer by the Episcopal Church and use the 1928 version for their services instead. In addition, Anglo-Catholic bodies may use the Anglican Missal, Anglican Service Book or English Missal when celebrating Mass.

A changing focus on social issues after the World War II led to Lambeth Conference resolutions countenancing contraception and the remarriage of divorced persons. Eventually, most provinces approved the ordination of women. In more recent years, some jurisdictions have permitted the ordination of people in same-sex relationships and authorised rites for the blessing of same-sex unions (see Homosexuality and Anglicanism). "The more liberal provinces that are open to changing Church doctrine on marriage in order to allow for same-sex unions include Brazil, Canada, New Zealand, Scotland, South India, South Africa, the US and Wales",[100][101] while the more conservative provinces are primarily located in the Global South.

The lack of social consensus among and within provinces of diverse cultural traditions has resulted in considerable conflict and even schism concerning some or all of these developments, as was the case in the Anglican realignment. More conservative elements within and outside of Anglicanism (primarily African churches and factions within North American Anglicanism) have opposed these changes,[102] while some liberal and moderate Anglicans see this opposition as representing a new fundamentalism within Anglicanism and "believe a split is inevitable and preferable to continued infighting and paralysis."[103] Some Anglicans opposed to various liberalising changes, in particular the ordination of women, have become Roman Catholics or Orthodox. Others have, at various times, joined the Continuing Anglican movement or departed for non-Anglican evangelical churches.

The term "Continuing Anglicanism" refers to a number of church bodies which have formed outside of the Anglican Communion in the belief that traditional forms of Anglican faith, worship, and order have been unacceptably revised or abandoned within some Anglican Communion churches in recent decades. They therefore claim that they are "continuing" traditional Anglicanism.

The modern Continuing Anglican movement principally dates to the Congress of St. Louis, held in the United States in 1977, where participants rejected changes that had been made in the Episcopal Church's Book of Common Prayer and also the Episcopal Church's approval of the ordination of women to the priesthood. More recent changes in the North American churches of the Anglican Communion, such as the introduction of same-sex marriage rites and the ordination of gay and lesbian people to the priesthood and episcopate, have created further separations.