Черный — это расовая классификация людей, обычно политическая и основанная на цвете кожи категория для определенных групп населения со средне- или темно-коричневым цветом кожи . Не все люди, считающиеся «черными», имеют темную кожу ; в некоторых странах, часто в социально-ориентированных системах расовой классификации в западном мире , термин «черный» используется для описания людей, которые воспринимаются как темнокожие по сравнению с другими группами населения. Он чаще всего используется для людей африканского происхождения к югу от Сахары , коренных австралийцев и меланезийцев , хотя он применялся во многих контекстах к другим группам и не является показателем какой-либо близкой родственной связи вообще. Коренные африканские общества не используют термин черный как расовую идентичность за пределами влияний, принесенных западными культурами.

Современные антропологи и другие ученые, признавая реальность биологического разнообразия между различными человеческими популяциями, рассматривают концепцию единой, различимой «черной расы» как социально сконструированную . Разные общества применяют разные критерии относительно того, кого классифицируют как «черного», и эти социальные конструкты менялись с течением времени. В ряде стран социальные переменные влияют на классификацию так же, как и цвет кожи, а социальные критерии «черноты» различаются. В Соединенном Королевстве «черный» исторически был эквивалентен « цветному человеку », общему термину для неевропейских народов. В то время как термин «цветной человек» широко используется и принимается в Соединенных Штатах , [1] близкий по звучанию термин « цветной человек » считается крайне оскорбительным, за исключением Южной Африки, где он является описанием человека смешанной расы . В других регионах, таких как Австралазия , поселенцы применяли прилагательное «черный» к коренному населению. Оно повсеместно считалось крайне оскорбительным в Австралии до 1960-х и 1970-х годов. «Черный» обычно не использовался как существительное, а скорее как прилагательное, определяющее какой-либо другой дескриптор (например, «черный ****»). По мере прогрессирования десегрегации после референдума 1967 года некоторые аборигены переняли этот термин, следуя американской моде, но он остается проблематичным. [2] Несколько американских руководств по стилю, [3] [4] включая AP Stylebook , изменили свои руководства, чтобы писать заглавную букву «b» в слове «black» после убийства в 2020 году Джорджа Флойда , афроамериканца . [3] [4] В руководстве по стилю ASA говорится, что «b» не следует писать с заглавной буквы. [5] Некоторые воспринимают термин «черный» как уничижительный, устаревший, уничижительный или иным образом нерепрезентативный ярлык и в результате не используют и не определяют его, особенно в африканских странах с незначительной или отсутствующей историей колониальной расовой сегрегации . [6]

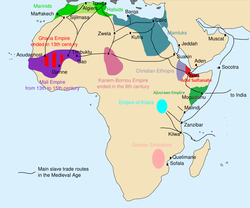

Многочисленные сообщества темнокожих людей присутствуют в Северной Африке , некоторые из них датируются доисторическими сообществами. Другие происходят от мигрантов через историческую транссахарскую торговлю или, после арабских вторжений в Северную Африку в 7 веке, от рабов из транссахарской работорговли в Северной Африке. [7] [8]

В XVIII веке марокканский султан Мулай Исмаил «Король-воин» (1672–1727) собрал корпус из 150 000 чернокожих солдат, назвав его Черной гвардией . [9] [10]

По словам Карлоса Мура , ученого-резидента бразильского Университета штата Баия, в 21 веке афро-многорасовые в арабском мире , включая арабов в Северной Африке, идентифицируют себя способами, которые напоминают многорасовых в Латинской Америке . Он утверждает, что арабы с более темным тоном кожи, как и латиноамериканцы с более темным тоном кожи , считают себя белыми, потому что у них есть отдаленные белые предки. [11]

У президента Египта Анвара Садата была мать, которая была темнокожей нубийской суданкой ( суданский араб ), и отец, который был светлокожим египтянином . В ответ на объявление о вакансии актера, будучи молодым человеком, он сказал: «Я не белый, но и не совсем черный. Моя чернота имеет тенденцию к красноватому оттенку». [12]

Из-за патриархальной природы арабского общества арабские мужчины, в том числе во время работорговли в Северной Африке, порабощали больше африканских женщин, чем мужчин. Рабынь часто заставляли работать в качестве домашней прислуги и в сельском хозяйстве. Мужчины интерпретировали Коран как разрешающий сексуальные отношения между мужчиной-хозяином и его порабощенными женщинами вне брака (см. Ma malakat aymanukum и секс ), [13] [14] что приводило к появлению множества детей смешанной расы . Когда порабощенная женщина беременела ребенком своего арабского хозяина, она считалась умм валад или «матерью ребенка», статус, который давал ей привилегированные права. Ребенку давались права наследования имущества отца, поэтому дети смешанной расы могли разделить любое богатство отца. [15] Поскольку общество было патрилинейным , дети наследовали социальный статус своих отцов при рождении и рождались свободными.

Некоторые дети смешанной расы наследовали своим отцам в качестве правителей, как, например, султан Ахмад аль-Мансур , правивший Марокко с 1578 по 1608 год. Технически он не считался ребенком смешанной расы раба; его мать была фулани и наложницей его отца. [15]

В начале 1991 года неарабы народа загава в Судане подтвердили, что они стали жертвами усиливающейся арабской кампании апартеида , сегрегирующей арабов и неарабов (в частности, людей нилотского происхождения). [16] Суданских арабов, которые контролировали правительство, широко называли практикующими апартеид против неарабских граждан Судана. Правительство обвиняли в «искусном манипулировании арабской солидарностью» для проведения политики апартеида и этнической чистки . [17]

Суданские арабы также являются чернокожими людьми, поскольку они являются культурно и лингвистически арабизированными коренными народами Судана, в основном нило-сахарского , нубийского [18] и кушитского [ 19] происхождения; их тон кожи и внешний вид напоминают других чернокожих людей.

Экономист Американского университета Джордж Айитти обвинил арабское правительство Судана в применении актов расизма в отношении чернокожих граждан. [20] По словам Айитти, «В Судане... арабы монополизировали власть и исключили чернокожих — арабский апартеид». [21] Многие африканские комментаторы присоединились к Айитти, обвинив Судан в применении арабского апартеида. [22]

В Сахаре коренные туарегские берберы держали рабов- негров . Большинство этих пленников были нило-сахарского происхождения и были либо куплены туарегской знатью на рынках рабов в Западном Судане , либо захвачены во время набегов. Их происхождение обозначено через берберское слово Ахаггар Ibenheren (ед. ч. Ébenher ), которое намекает на рабов, которые говорили только на нило-сахарском языке. Эти рабы также иногда были известны под заимствованным сонгайским термином Bella . [23]

Аналогичным образом, коренные народы Сахарави в Западной Сахаре наблюдали классовую систему, состоящую из высоких каст и низких каст. За пределами этих традиционных племенных границ находились «негритянские» рабы, которых набирали из близлежащих районов. [24]

В Эфиопии и Сомали классы рабов в основном состояли из захваченных народов с судано-эфиопских и кенийско-сомалийских международных границ [25] или других прилегающих районов нилотских и банту народов, которые были известны под общим названием Shanqella [26] и Adone (оба аналога «negro» в англоязычном контексте). [27] Некоторые из этих рабов были захвачены во время территориальных конфликтов на Африканском Роге, а затем проданы работорговцам. [28] Самое раннее представление этой традиции датируется надписью седьмого или восьмого века до нашей эры, принадлежащей королевству Дамат . [29]

Эти пленники и другие с аналогичной морфологией были выделены как tsalim barya (темнокожие рабы) в отличие от знати, говорящей на афразийском языке, или saba qayh («красные люди») или светлокожие рабы; в то время как, с другой стороны, западные стандарты расовых категорий не делают различий между saba qayh («красные люди» — светлокожие) или saba tiqur («черные люди» — темнокожие) африканцами из Рога (говорящими на афразийском языке, нилотском языке или банту), таким образом, считая всех их «черными людьми» (и в некоторых случаях «неграми») в соответствии с понятием расы западного общества. [30] [31] [32]

В Южной Африке период колонизации привел к многочисленным союзам и бракам между европейцами и африканцами ( народы банту Южной Африки и койсаны ) из разных племен, в результате чего рождались дети смешанной расы. По мере того, как европейские колонизаторы захватывали контроль над территорией, они, как правило, оттесняли смешанную расу и африканское население во второсортный статус. В течение первой половины 20-го века правительство, в котором доминировали белые, классифицировало население по четырем основным расовым группам: черные , белые , азиаты (в основном индийцы ) и цветные . Цветная группа включала людей смешанного банту, койсанского и европейского происхождения (с некоторой долей малайского происхождения, особенно в Западной Капской провинции ). Определение «цветные» занимало промежуточное политическое положение между определениями «черные» и «белые» в Южной Африке. Оно навязывало систему правовой расовой сегрегации, комплекс законов, известный как апартеид .

Бюрократия апартеида разработала сложные (и часто произвольные) критерии в Законе о регистрации населения 1945 года, чтобы определить, кто принадлежит к какой группе. Младшие должностные лица проводили тесты для обеспечения соблюдения классификаций. Когда по внешнему виду человека было неясно, следует ли считать его цветным или черным, использовался « карандашный тест ». Карандаш вставлялся в волосы человека, чтобы определить, достаточно ли курчавы волосы, чтобы удержать карандаш, вместо того, чтобы пропускать его сквозь волосы, как это было бы с более гладкими волосами. Если да, то человека классифицировали как черного. [33] Такие классификации иногда разделяли семьи.

Сандра Лэнг — южноафриканская женщина, которую власти классифицировали как цветную в эпоху апартеида из-за цвета кожи и текстуры волос , хотя ее родители могли доказать, что у нее было не менее трех поколений европейских предков. В возрасте 10 лет ее исключили из школы для белых. Решения чиновников, основанные на ее аномальной внешности, разрушили ее семью и взрослую жизнь. Она стала героиней биографического драматического фильма 2008 года «Кожа» , который получил множество наград. В эпоху апартеида те, кого классифицировали как «цветных», подвергались притеснениям и дискриминации. Но у них были ограниченные права и в целом они находились в немного лучших социально-экономических условиях, чем те, кого классифицировали как «черных». Правительство требовало, чтобы черные и цветные жили в районах, отделенных от белых, создавая большие поселки, расположенные вдали от городов, в качестве районов для черных.

В эпоху после апартеида Конституция Южной Африки провозгласила страну «нерасовой демократией». В попытке исправить прошлые несправедливости правительство АНК приняло законы в поддержку политики позитивных действий для чернокожих; в соответствии с ними они определяют «черных» людей как «африканцев», «цветных» и «азиатов». Некоторые политики позитивных действий отдают предпочтение «африканцам» перед «цветными» с точки зрения права на определенные льготы. Некоторые южноафриканцы, отнесенные к категории «африканских черных», говорят, что «цветные» не страдали так сильно, как во времена апартеида. Известно, что «цветные» южноафриканцы обсуждают свою дилемму, говоря: «мы были недостаточно белыми при апартеиде, и мы недостаточно черными при АНК ( Африканском национальном конгрессе )». [34] [35] [36]

В 2008 году Верховный суд Южной Африки постановил, что китайские южноафриканцы , проживавшие в эпоху апартеида (и их потомки), должны быть переклассифицированы в «черных людей» исключительно в целях доступа к льготам позитивной дискриминации, поскольку они также были «ущемлены» расовой дискриминацией. Китайцы, прибывшие в страну после окончания апартеида, не имеют права на такие льготы. [37]

Помимо внешнего вида, «цветных» обычно можно отличить от «черных» по языку. Большинство говорят на африкаанс или английском как на родном языке , в отличие от языков банту , таких как зулу или коса . У них также, как правило, больше европейских имен, чем имен банту . [38]

« Афро-азиаты » или «афро-азиаты» — это люди смешанного африканского и азиатского происхождения, живущие к югу от Сахары. В Соединенных Штатах их также называют «черными азиатами» или «блазианцами». [39] Исторически афро-азиатское население было маргинализировано в результате миграции людей и социальных конфликтов. [40]

В средневековом арабском мире этническое обозначение «черный» охватывало не только зандж , или африканцев, но и такие сообщества, как зутт , синди и индийцы с индийского субконтинента . [41] Историки подсчитали, что между приходом ислама в 650 году н. э. и отменой рабства на Аравийском полуострове в середине 20-го века, от 10 до 18 миллионов черных африканцев (известных как зандж) были порабощены восточноафриканскими работорговцами и перевезены на Аравийский полуостров и в соседние страны. [42] Это число намного превысило количество рабов, которые были вывезены в Америку. [43] Рабство в Саудовской Аравии и рабство в Йемене было отменено в 1962 году, рабство в Дубае в 1963 году, а рабство в Омане в 1970 году. [44]

Несколько факторов повлияли на видимость потомков этой диаспоры в арабских обществах 21-го века: торговцы отправляли больше женщин-рабынь, чем мужчин, поскольку на них был спрос, чтобы они служили наложницами в гаремах на Аравийском полуострове и в соседних странах. Мужчин-рабов кастрировали, чтобы они служили охранниками гарема . Число погибших чернокожих африканских рабов от принудительного труда было высоким. Дети смешанной расы женщин-рабынь и арабских владельцев ассимилировались в семьях арабских владельцев по системе патрилинейного родства . В результате на Аравийском полуострове и в соседних странах сохранилось немного самобытных афро-арабских общин. [45] [46]

Отдельные и самоидентифицированные черные общины были зарегистрированы в таких странах, как Ирак, с 1,2 миллионами черных людей ( афроиракцев ), и они свидетельствуют об истории дискриминации. Эти потомки занджа добивались статуса меньшинства от правительства, которое зарезервировало бы некоторые места в парламенте для представителей их населения. [47] По словам Аламина М. Мазруи и др., в целом на Аравийском полуострове и в соседних странах большинство этих общин идентифицируют себя как черные и арабские. [48]

Афроиранцы — это люди чёрного африканского происхождения, проживающие в Иране. Во времена династии Каджаров многие богатые семьи импортировали чёрных африканских женщин и детей в качестве рабов для выполнения домашней работы. Этот рабский труд был получен исключительно от зинджей, которые были бантуязычными народами, которые жили вдоль Великих африканских озёр , в районе, примерно включающем современные Танзанию , Мозамбик и Малави . [49] [50]

Около 150 000 восточноафриканцев и чернокожих проживают в Израиле , что составляет чуть более 2% населения страны. Подавляющее большинство из них, около 120 000, являются бета-израильтянами , [51] большинство из которых являются недавними иммигрантами, приехавшими в 1980-х и 1990-х годах из Эфиопии . [52] Кроме того, в Израиле проживает более 5000 членов движения африканских евреев-израильтян Иерусалима , которые являются потомками афроамериканцев , эмигрировавших в Израиль в 20 веке, и которые проживают в основном в отдельном районе в городе Негев Димона . Неизвестное количество чернокожих, принявших иудаизм, проживают в Израиле, большинство из них — новообращенные из Соединенного Королевства, Канады и Соединенных Штатов.

Кроме того, в Израиле находится около 60 000 нееврейских африканских иммигрантов, некоторые из которых искали убежища. Большинство мигрантов — выходцы из общин в Судане и Эритрее , в частности, из групп нуба, говорящих на нигерийско-конголезском языке , из южных Нубийских гор ; некоторые из них — нелегальные иммигранты. [53] [54]

Начиная с нескольких столетий назад, в период Османской империи , десятки тысяч пленников -занджей были доставлены работорговцами на плантации и сельскохозяйственные угодья, расположенные между Антальей и Стамбулом , что дало начало афро -турецкому населению в современной Турции . [55] Часть их предков осталась на месте , а многие мигрировали в более крупные города и поселки. Другие чернокожие рабы были перевезены на Крит , откуда они или их потомки позже достигли района Измира через обмен населением между Грецией и Турцией в 1923 году или косвенно из Айвалыка в поисках работы. [56]

Помимо исторического присутствия афро-турок, Турция также принимает значительное количество иммигрантов-чернокожих с конца 1990-х годов. Сообщество состоит в основном из современных иммигрантов из Ганы, Эфиопии, ДРК, Судана, Нигерии, Кении, Эритреи, Сомали и Сенегала. Согласно официальным данным, в Турции проживает 1,5 миллиона африканцев, и около 25% из них находятся в Стамбуле . [57] Другие исследования утверждают, что большинство африканцев в Турции проживает в Стамбуле, и сообщают, что в Тарлабаши , Долапдере , Кумкапы , Йеникапы и Куртулуше наблюдается сильное африканское присутствие. [58]

Большинство африканских иммигрантов в Турции приезжают в Турцию, чтобы мигрировать в Европу. Иммигранты из Восточной Африки обычно являются беженцами, в то время как иммиграция из Западной и Центральной Африки, как сообщается, обусловлена экономическими причинами. [58] Сообщается, что африканские иммигранты в Турции регулярно сталкиваются с экономическими и социальными проблемами, в частности, с расизмом и противодействием иммиграции со стороны местных жителей. [59]

Сидди — этническая группа, населяющая Индию и Пакистан . Члены группы произошли от народов банту из Юго-Восточной Африки . Некоторые из них были торговцами, моряками, наемными слугами , рабами или наемниками. В настоящее время численность населения сидди оценивается в 270 000–350 000 человек, проживающих в основном в Карнатаке , Гуджарате и Хайдарабаде в Индии, а также в Макране и Карачи в Пакистане. [60] В полосе Макрана провинций Синд и Белуджистан на юго-западе Пакистана эти потомки банту известны как макрани. [61] В 1960-х годах в Синде было кратковременное движение «Черная сила», и многие сидди гордятся своим африканским происхождением и отмечают его. [62] [63]

.jpg/440px-TreeMix_analysis_of_worldwide_populations_(2022).jpg)

Негритосы — это совокупность различных, часто неродственных народов, которые когда-то считались единой отдельной популяцией близкородственных групп, но генетические исследования показали, что они произошли от той же древней восточно-евразийской метапопуляции, которая дала начало современным восточноазиатским народам , и состоят из нескольких отдельных групп, а также демонстрируют генетическую гетерогенность. [64] [65] [66] Они населяют изолированные части Юго-Восточной Азии и в настоящее время в основном ограничены Южным Таиландом, [67] Малайским полуостровом и Андаманскими островами Индии. [68]

Negrito означает «маленькие черные люди» на испанском языке (negrito — это испанское уменьшительное от negro, т. е. «маленький черный человек»); так испанцы называли аборигенов, с которыми они столкнулись на Филиппинах . [69] Сам термин Negrito подвергся критике в таких странах, как Малайзия, где он теперь взаимозаменяем с более приемлемым Semang , [70] хотя этот термин на самом деле относится к определенной группе.

У них темная кожа, часто вьющиеся волосы и азиатские черты лица, они крепкого телосложения. [71] [72] [73]

Негритосы на Филиппинах часто сталкиваются с дискриминацией. Из-за своего традиционного образа жизни охотников-собирателей они маргинализированы и живут в нищете, не имея возможности найти работу. [74]

.jpg/440px-Hyacinthe_Rigaud_-_Jeune_nègre_avec_un_arc_(ca.1697).jpg)

Хотя сбор данных об этническом происхождении во Франции является незаконным , по оценкам, там проживает около 2,5–5 миллионов чернокожих людей. [75] [76]

По состоянию на 2020 год в Германии проживает около миллиона чернокожих людей. [77]

Афроголландцы — это жители Нидерландов , которые имеют чернокожее африканское или афро-карибское происхождение. Как правило, они из бывших и нынешних голландских заморских территорий Аруба , Бонайре , Кюрасао , Синт-Мартен и Суринам . В Нидерландах также есть значительные общины выходцев из Кабо-Верде и других африканских стран.

По состоянию на 2021 год в Португалии проживало не менее 232 000 человек недавнего происхождения из числа чернокожих африканских иммигрантов . В основном они проживают в регионах Лиссабон , Порту , Коимбра . Поскольку Португалия не собирает информацию об этнической принадлежности, оценка включает только людей, которые по состоянию на 2021 год имели гражданство страны Африки к югу от Сахары или людей, которые получили португальское гражданство в период с 2008 по 2021 год, таким образом исключая потомков, людей более дальнего африканского происхождения или людей, которые поселились в Португалии несколько поколений назад и теперь являются гражданами Португалии . [78] [79]

Термин « мавры » использовался в Европе в более широком, несколько уничижительном смысле для обозначения мусульман , [80] особенно тех, кто имел арабское или берберское происхождение, независимо от того, жили ли они в Северной Африке или на Иберии. [81] Мавры не были отдельным или самоопределяющимся народом. [82] Европейцы Средневековья и раннего Нового времени применяли это название к мусульманским арабам, берберам, африканцам к югу от Сахары и европейцам. [83]

Исидор Севильский , писавший в VII веке, утверждал, что латинское слово Maurus произошло от греческого mauron , μαύρον, что по-гречески означает «черный». Действительно, к тому времени, когда Исидор Севильский пришел писать свои «Этимологии» , слово Maurus или «мавр» стало прилагательным в латыни, «ибо греки называли черного mauron». «Во времена Исидора мавры были черными по определению...» [84]

Афроиспанцы — это испанские граждане западно- и центральноафриканского происхождения . Сегодня они в основном из Камеруна , Экваториальной Гвинеи , Ганы , Гамбии , Мали , Нигерии и Сенегала. Кроме того, многие афроиспанцы, родившиеся в Испании, родом из бывшей испанской колонии Экваториальная Гвинея . Сегодня в Испании насчитывается около 683 000 афроиспанцев .

По данным Управления национальной статистики , по переписи 2001 года в Соединенном Королевстве проживало более миллиона чернокожих; 1% от общей численности населения описывали себя как «черные карибцы», 0,8% как «черные африканцы» и 0,2% как «черные другие». [85] Великобритания поощряла иммиграцию рабочих из стран Карибского бассейна после Второй мировой войны; первым символическим движением были те, кто прибыл на корабле Empire Windrush , и, следовательно, те, кто мигрировал между 1948 и 1970 годами, известны как поколение Windrush . Предпочтительным официальным зонтичным термином является «черные, азиатские и этнические меньшинства» ( BAME ), но иногда термин «черный» используется сам по себе, чтобы выразить объединенную оппозицию расизму , как в Southall Black Sisters , которая начинала с преимущественно британского азиатского избирательного округа, и в Национальной ассоциации черной полиции , в состав которой входят «африканцы, афро-карибцы и азиаты по происхождению». [86]

Когда африканские государства стали независимыми в 1960-х годах, Советский Союз предложил многим своим гражданам возможность учиться в России . За 40 лет около 400 000 африканских студентов из разных стран переехали в Россию, чтобы продолжить обучение, среди них было много чернокожих африканцев. [87] [88] Это распространилось за пределы Советского Союза на многие страны Восточного блока .

Из-за работорговли в Османской империи , которая процветала на Балканах , в прибрежном городе Ульцинь в Черногории была своя собственная черная община. [89] В 1878 году эта община состояла примерно из 100 человек. [90]

Коренных австралийцев называли «черными людьми» в Австралии с первых дней европейского поселения . [91] Хотя изначально этот термин был связан с цветом кожи , сегодня он используется для обозначения происхождения аборигенов или жителей островов Торресова пролива в целом и может относиться к людям с любой пигментацией кожи. [92]

В Австралии в XIX и начале XX веков идентификация как «черного» или «белого» имела решающее значение для трудоустройства и социальных перспектив. Были созданы различные государственные советы по защите аборигенов , которые фактически полностью контролировали жизнь коренных австралийцев — где они жили, их работу, брак, образование, а также имели право разлучать детей с родителями. [93] [94] [95] Аборигенам не разрешалось голосовать, и их часто ограничивали резервациями и заставляли заниматься низкооплачиваемым или фактически рабским трудом. [96] [97] Социальное положение людей смешанной расы или « полукровок » менялось со временем. В отчете Болдуина Спенсера за 1913 год говорится, что:

метисы не принадлежат ни к аборигенам, ни к белым, однако в целом они больше склоняются к первым; ... Одно несомненно, а именно, что белое население в целом никогда не будет смешиваться с метисами... лучшее и самое доброе, что можно сделать, это поместить их в резервации вместе с туземцами, обучать их в тех же школах и поощрять их вступать в браки между собой. [98]

Однако после Первой мировой войны стало очевидно, что число людей смешанной расы растет более быстрыми темпами, чем белое население, и к 1930 году страх перед «угрозой полукровок», подрывающей идеал Белой Австралии изнутри, стал восприниматься как серьезная проблема. [99] Сесил Кук , защитник коренных народов Северной территории , отметил, что:

Обычно к пятому и неизменно к шестому поколению все исконные черты австралийских аборигенов искореняются. Проблема наших метисов быстро исчезнет благодаря полному исчезновению черной расы и быстрому погружению их потомства в белую. [100]

Официальной политикой стала политика биологической и культурной ассимиляции : «Устраните чистокровных и разрешите примесь белой крови к полукровкам, и в конечном итоге раса станет белой». [101] Это привело к разному отношению к «черным» и «полукровкам»: людей с более светлой кожей стали отбирать из семей, чтобы воспитывать как «белых» людей и запрещать им говорить на родном языке и соблюдать традиционные обычаи, процесс, который теперь известен как « украденное поколение» . [102]

Со второй половины 20-го века и до настоящего времени наблюдается постепенный сдвиг в сторону улучшения прав человека для аборигенов. На референдуме 1967 года более 90% населения Австралии проголосовали за прекращение конституционной дискриминации и включение аборигенов в национальную перепись . [103] В этот период многие активисты-аборигены начали принимать термин «черный» и использовать свое происхождение как источник гордости. Активист Боб Маза сказал:

Я только надеюсь, что когда я умру, я смогу сказать, что я черный и что быть черным прекрасно. Именно это чувство гордости мы пытаемся вернуть аборигенам [ sic ] сегодня. [104]

В 1978 году писатель-абориген Кевин Гилберт получил премию Национального книжного совета за свою книгу Living Black: Blacks Talk to Kevin Gilbert , сборник рассказов аборигенов, а в 1998 году был награжден (но отказался принять) Премией за права человека в области литературы за Inside Black Australia , поэтическую антологию и выставку фотографий аборигенов. [105] В отличие от предыдущих определений, основанных исключительно на степени аборигенного происхождения, правительство изменило юридическое определение аборигена в 1990 году, включив в него любого:

лицо, происходящее от аборигенов или жителей островов Торресова пролива, которое идентифицирует себя как аборигена или жителя островов Торресова пролива и принимается таковым сообществом, в котором он [или она] живет [106]

Это общенациональное принятие и признание аборигенов привело к значительному увеличению числа людей, идентифицирующих себя как аборигенов или жителей островов Торресова пролива. [107] [108] Повторное присвоение термина «черный» с положительным и более инклюзивным значением привело к его широкому использованию в основной австралийской культуре, включая государственные средства массовой информации, [109] правительственные учреждения, [110] и частные компании. [111] В 2012 году ряд громких дел подчеркнул правовое и общественное отношение к тому, что идентификация в качестве аборигена или жителя островов Торресова пролива не зависит от цвета кожи, при этом известный боксер Энтони Мандин подвергся широкой критике за то, что поставил под сомнение «черноту» другого боксера [112] , а журналист Эндрю Болт был успешно привлечен к ответственности за публикацию дискриминационных комментариев об аборигенах со светлой кожей. [113]

The region of Melanesia is named from Greek μέλας, black, and νῆσος, island, etymologically meaning "islands of black [people]", in reference to the dark skin of the indigenous peoples. Early European settlers, such as Spanish explorer Yñigo Ortiz de Retez, noted the resemblance of the people to those in Africa.[114]

Melanesians, along with other Pacific Islanders, were frequently deceived or coerced during the 19th and 20th centuries into forced labour for sugarcane, cotton, and coffee planters in countries distant to their native lands in a practice known as blackbirding. In Queensland, some 55,000 to 62,500[115] were brought from the New Hebrides, the Solomon Islands, and New Guinea to work in sugarcane fields. Under the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901, most islanders working in Queensland were repatriated back to their homelands.[116] Those who remained in Australia, commonly called South Sea Islanders, often faced discrimination similarly to Indigenous Australians by white-dominated society. Many indigenous rights activists have South Sea Islander ancestry, including Faith Bandler, Evelyn Scott and Bonita Mabo.

Many Melanesians have taken up the term 'Melanesia' as a way to empower themselves as a collective people. Stephanie Lawson writes that the term "moved from a term of denigration to one of affirmation, providing a positive basis for contemporary subregional identity as well as a formal organisation".[117]: 14 For instance, the term is used in the Melanesian Spearhead Group, which seeks to promote economic growth among Melanesian countries.

John Caesar, nicknamed "Black Caesar", a convict and bushranger with parents born in an unknown area in Africa, was one of the first people of recent black African ancestry to arrive in Australia.[118]

At the 2006 Census, 248,605 residents declared that they were born in Africa. This figure pertains to all immigrants to Australia who were born in nations in Africa regardless of race, and includes white Africans.

"Black Canadians" is a designation used for people of black African ancestry who are citizens or permanent residents of Canada.[119][120] The majority of black Canadians are of Caribbean origin, though the population also consists of African American immigrants and their descendants (including black Nova Scotians), as well as many African immigrants.[121][122]

Black Canadians often draw a distinction between those of Afro-Caribbean ancestry and those of other African roots. The term African Canadian is occasionally used by some black Canadians who trace their heritage to the first slaves brought by British and French colonists to the North American mainland.[120] Promised freedom by the British during the American Revolutionary War, thousands of Black Loyalists were resettled by the Crown in Canada afterward, such as Thomas Peters. In addition, an estimated ten to thirty thousand fugitive slaves reached freedom in Canada from the Southern United States during the Antebellum years, aided by people along the Underground Railroad.

Many black people of Caribbean origin in Canada reject the term "African Canadian" as an elision of the uniquely Caribbean aspects of their heritage,[123] and instead identify as Caribbean Canadian.[123] Unlike in the United States, where "African American" has become a widely used term, in Canada controversies associated with distinguishing African or Caribbean heritage have resulted in the term "black Canadian" being widely accepted there.[124]

There were eight principal areas used by Europeans to buy and ship slaves to the Western Hemisphere. The number of enslaved people sold to the New World varied throughout the slave trade. As for the distribution of slaves from regions of activity, certain areas produced far more enslaved people than others. Between 1650 and 1900, 10.24 million enslaved West Africans arrived in the Americas from the following regions in the following proportions:[125]

.jpg/440px-Slave_trade_from_Africa_to_the_Americas_(8928374600).jpg)

By the early 1900s, nigger had become a pejorative word in the United States. In its stead, the term colored became the mainstream alternative to negro and its derived terms. After the American Civil Rights Movement, the terms colored and negro gave way to "black". Negro had superseded colored as the most polite word for African Americans at a time when black was considered more offensive.[126][failed verification] This term was accepted as normal, including by people classified as Negroes, until the later Civil Rights movement in the late 1960s. One well-known example is the use by Dr. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. of "Negro" in his famous speech of 1963, I Have a Dream. During the American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, some African-American leaders in the United States, notably Malcolm X, objected to the word Negro because they associated it with the long history of slavery, segregation, and discrimination that treated African Americans as second-class citizens, or worse.[127] Malcolm X preferred Black to Negro, but later gradually abandoned that as well for Afro-American after leaving the Nation of Islam.[128]

Since the late 1960s, various other terms for African Americans have been more widespread in popular usage. Aside from black American, these include Afro-American (in use from the late 1960s to 1990) and African American (used in the United States to refer to Black Americans, people often referred to in the past as American Negroes).[129]

In the first 200 years that black people were in the United States, they primarily identified themselves by their specific ethnic group (closely allied to language) and not by skin color. Individuals identified themselves, for example, as Ashanti, Igbo, Bakongo, or Wolof. However, when the first captives were brought to the Americas, they were often combined with other groups from West Africa, and individual ethnic affiliations were not generally acknowledged by English colonists. In areas of the Upper South, different ethnic groups were brought together. This is significant as the captives came from a vast geographic region: the West African coastline stretching from Senegal to Angola and in some cases from the south-east coast such as Mozambique. A new African-American identity and culture was born that incorporated elements of the various ethnic groups and of European cultural heritage, resulting in fusions such as the Black church and African-American English. This new identity was based on provenance and slave status rather than membership in any one ethnic group.[130]

By contrast, slave records from Louisiana show that the French and Spanish colonists recorded more complete identities of the West Africans, including ethnicities and given tribal names.[131]

The U.S. racial or ethnic classification "black" refers to people with all possible kinds of skin pigmentation, from the darkest through to the very lightest skin colors, including albinos, if they are believed by others to have African ancestry (in any discernible percentage). There are also certain cultural traits associated with being "African American", a term used effectively as a synonym for "black person" within the United States.

In March 1807, Great Britain, which largely controlled the Atlantic, declared the transatlantic slave trade illegal, as did the United States. (The latter prohibition took effect 1 January 1808, the earliest date on which Congress had the power to do so after protecting the slave trade under Article I, Section 9 of the United States Constitution.)

By that time, the majority of black people in the United States were native-born, so the use of the term "African" became problematic. Though initially a source of pride, many blacks feared that the use of African as an identity would be a hindrance to their fight for full citizenship in the United States. They also felt that it would give ammunition to those who were advocating repatriating black people back to Africa. In 1835, black leaders called upon Black Americans to remove the title of "African" from their institutions and replace it with "Negro" or "Colored American". A few institutions chose to keep their historic names, such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church. African Americans popularly used the terms "Negro" or "colored" for themselves until the late 1960s.[132]

The term black was used throughout but not frequently since it carried a certain stigma. In his 1963 "I Have a Dream" speech,[133] Martin Luther King Jr. uses the terms negro fifteen times and black four times. Each time that he uses black, it is in parallel construction with white; for example, "black men and white men".[134]

With the successes of the American Civil Rights Movement, a new term was needed to break from the past and help shed the reminders of legalized discrimination. In place of Negro, activists promoted the use of black as standing for racial pride, militancy, and power. Some of the turning points included the use of the term "Black Power" by Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael) and the popular singer James Brown's song "Say It Loud – I'm Black and I'm Proud".

In 1988, the civil rights leader Jesse Jackson urged Americans to use instead the term "African American" because it had a historical cultural base and was a construction similar to terms used by European descendants, such as German American, Italian American, etc. Since then, African American and black have often had parallel status. However, controversy continues over which, if any, of the two terms is more appropriate. Maulana Karenga argues that the term African-American is more appropriate because it accurately articulates their geographical and historical origin.[citation needed] Others have argued that "black" is a better term because "African" suggests foreignness, although black Americans helped found the United States.[135] Still others believe that the term "black" is inaccurate because African Americans have a variety of skin tones.[136][137] Some surveys suggest that the majority of Black Americans have no preference for "African American" or "black",[138] although they have a slight preference for "black" in personal settings and "African American" in more formal settings.[139]

In the U.S. census race definitions, black and African Americans are citizens and residents of the United States with origins in the black racial groups of Africa.[140] According to the Office of Management and Budget, the grouping includes individuals who self-identify as African American, as well as persons who emigrated from nations in the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa.[141] The grouping is thus based on geography, and may contradict or misrepresent an individual's self-identification, since not all immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa are "black".[140] The Census Bureau also notes that these classifications are socio-political constructs and should not be interpreted as scientific or anthropological.[142]

According to U.S. Census Bureau data, African immigrants generally do not self-identify as African American. The overwhelming majority of African immigrants identify instead with their own respective ethnicities (~95%).[143] Immigrants from some Caribbean, Central American and South American nations and their descendants may or may not also self-identify with the term.[144]

Recent surveys of African Americans using a genetic testing service have found varied ancestries that show different tendencies by region and sex of ancestors. These studies found that on average, African Americans have 73.2–80.9% West African, 18–24% European, and 0.8–0.9% Native American genetic heritage, with large variation between individuals.[145][146][147]

According to studies in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, U.S. residents consistently overestimate the size, physical strength, and formidability of young black men.[148]

The New Great Migration is not evenly distributed throughout the South. As with the earlier Great Migration, the New Great Migration is primarily directed toward cities and large urban areas, such as Atlanta, Charlotte, Houston, Dallas, Raleigh, Washington, D.C., Tampa, Virginia Beach, San Antonio, Memphis, Orlando, Nashville, Jacksonville, and so forth. North Carolina's Charlotte metro area in particular, is a hot spot for African American migrants in the US. Between 1975 and 1980, Charlotte saw a net gain of 2,725 African Americans in the area. This number continued to rise as between 1985 and 1990 as the area had a net gain of 7,497 African Americans, and from 1995 to 2000 the net gain was 23,313 African Americans.

This rise in net gain points to Atlanta, Charlotte, Dallas, and Houston being a growing hot spots for the migrants of The New Great Migration. The percentage of Black Americans who live in the South has been increasing since 1990, and the biggest gains have been in the region's large urban areas, according to census data. The Black population of metro Atlanta more than doubled between 1990 and 2020, surpassing 2 million in the most recent census. The Black population also more than doubled in metro Charlotte while Greater Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth both saw their Black populations surpass 1 million for the first time. Several smaller metro areas also saw sizable gains, including San Antonio;[149] Raleigh and Greensboro, N.C.; and Orlando.[150] Primary destinations are states that have the most job opportunities, especially Georgia, North Carolina, Maryland, Virginia, Tennessee, Florida and Texas. Other southern states, including Mississippi, Louisiana, South Carolina, Alabama and Arkansas, have seen little net growth in the African American population from return migration.

.jpg/440px-Frederick_Douglass_(circa_1879).jpg)

From the late 19th century, the South used a colloquial term, the one-drop rule, to classify as black a person of any known African ancestry. This practice of hypodescent was not put into law until the early 20th century.[151] Legally, the definition varied from state to state. Racial definition was more flexible in the 18th and 19th centuries before the American Civil War. For instance, President Thomas Jefferson held in slavery persons who were legally white (less than 25% black) according to Virginia law at the time, but, because they were born to slave mothers, they were born into slavery, according to the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, which Virginia adopted into law in 1662.

Outside of the United States, some other countries have adopted the one-drop rule, but the definition of who is black and the extent to which the one-drop "rule" applies varies greatly from country to country.

The one-drop rule may have originated as a means of increasing the number of black slaves[152] and was maintained as an attempt to keep the white race "pure".[153][unreliable source] One of the results of the one-drop rule was the uniting of the African-American community.[151] Some of the most prominent abolitionists and civil-rights activists of the 19th century were multiracial, such as Frederick Douglass, Robert Purvis and James Mercer Langston. They advocated equality for all.

The concept of blackness in the United States has been described as the degree to which one associates themselves with mainstream African-American culture, politics,[158][159] and values.[160] To a certain extent, this concept is not so much about race but more about political orientation,[158][159] culture and behavior. Blackness can be contrasted with "acting white", where black Americans are said to behave with assumed characteristics of stereotypical white Americans with regard to fashion, dialect, taste in music,[161] and possibly, from the perspective of a significant number of black youth, academic achievement.[162]

Due to the often political[158][159] and cultural contours of blackness in the United States, the notion of blackness can also be extended to non-black people. Toni Morrison once described Bill Clinton as the first black President of the United States,[163] because, as she put it, he displayed "almost every trope of blackness".[164] Clinton welcomed the label.[165]

The question of blackness also arose in the Democrat Barack Obama's 2008 presidential campaign. Commentators questioned whether Obama, who was elected the first president with black ancestry, was "black enough", contending that his background is not typical because his mother was a white American and his father was a black student visitor from Kenya.[155][157] Obama chose to identify as black and African American.[166]

The 2015 preliminary survey to the 2020 census allowed Afro-Mexicans to self-identify for the first time in Mexico and recorded a total of 1.4 million (1.2% of the total Mexican population). The majority of Afro-Mexicans live in the Costa Chica of Guerrero region.[167]

The first Afro-Dominican slaves were shipped to the Dominican Republic by Spanish conquistadors during the Transatlantic slave trade.

Spanish conquistadors shipped slaves from West Africa to Puerto Rico. Afro-Puerto Ricans in part trace ancestry to this colonization of the island.

Approximately 12 million people were shipped from Africa to the Americas during the Atlantic slave trade from 1492 to 1888. Of these, 11.5 million of those shipped to South America and the Caribbean.[168] Brazil was the largest importer in the Americas, with 5.5 million African slaves imported, followed by the British Caribbean with 2.76 million, the Spanish Caribbean and Spanish Mainland with 1.59 million Africans, and the French Caribbean with 1.32 million.[169] Today their descendants number approximately 150 million in South America and the Caribbean.[170] In addition to skin color, other physical characteristics such as facial features and hair texture are often variously used in classifying peoples as black in South America and the Caribbean.[171][172] In South America and the Caribbean, classification as black is also closely tied to social status and socioeconomic variables, especially in light of social conceptions of "blanqueamiento" (racial whitening) and related concepts.[172][173]

The concept of race in Brazil is complex. A Brazilian child was never automatically identified with the racial type of one or both of their parents, nor were there only two categories to choose from. Between an individual of unmixed West African ancestry and a very light mulatto individual, more than a dozen racial categories were acknowledged, based on various combinations of hair color, hair texture, eye color, and skin color. These types grade into each other like the colors of the spectrum, and no one category stands significantly isolated from the rest. In Brazil, people are classified by appearance, not heredity.[174]

Scholars disagree over the effects of social status on racial classifications in Brazil. It is generally believed that achieving upward mobility and education results in individuals being classified as a category of lighter skin. The popular claim is that in Brazil, poor whites are considered black and wealthy blacks are considered white. Some scholars disagree, arguing that "whitening" of one's social status may be open to people of mixed race, a large part of the population known as pardo, but a person perceived as preto (black) will continue to be classified as black regardless of wealth or social status.[175][176]

From the years 1500 to 1850, an estimated 3.5 million captives were forcibly shipped from West/Central Africa to Brazil. The territory received the highest number of slaves of any country in the Americas.[178] Scholars estimate that more than half of the Brazilian population is at least in part descended from these individuals. Brazil has the largest population of Afro-ancestry outside Africa. In contrast to the US, during the slavery period and after, the Portuguese colonial government in Brazil and the later Brazilian government did not pass formal anti-miscegenation or segregation laws. As in other Latin American countries, intermarriage was prevalent during the colonial period and continued afterward. In addition, people of mixed race (pardo) often tended to marry white spouses, and their descendants became accepted as white. As a result, some of the European descended population also has West African or Amerindian blood. According to the last census of the 20th century, in which Brazilians could choose from five color/ethnic categories with which they identified, 54% of individuals identified as white, 6.2% identified as black, and 39.5% identified as pardo (brown)—a broad multi-racial category, including tri-racial persons.[179]

In the 19th century, a philosophy of racial whitening emerged in Brazil, related to the assimilation of mixed-race people into the white population through intermarriage. Until recently the government did not keep data on race. However, statisticians estimate that in 1835, roughly 50% of the population was preto (black; most were enslaved), a further 20% was pardo (brown), and 25% white, with the remainder Amerindian. Some classified as pardo were tri-racial.

By the 2000 census, demographic changes including the end to slavery, immigration from Europe and Asia, assimilation of multiracial persons, and other factors resulted in a population in which 6.2% of the population identified as black, 40% as pardo, and 55% as white. Essentially most of the black population was absorbed into the multi-racial category by intermixing.[174] A 2007 genetic study found that at least 29% of the middle-class, white Brazilian population had some recent (since 1822 and the end of the colonial period) African ancestry.[180]

According to the 2022 census, 10.2% of Brazilians said they were black, compared with 7.6% in 2010, and 45.3% said they were racially mixed, up from 43.1%, while the proportion of self-declared white Brazilians has fallen from 47.7% to 43.5%. Activists from Brazil’s Black movement attribute the racial shift in the population to a growing sense of pride among African-descended Brazilians in recognising and celebrating their ancestry.[181]

The philosophy of the racial democracy in Brazil has drawn some criticism, based on economic issues. Brazil has one of the largest gaps in income distribution in the world. The richest 10% of the population earn 28 times the average income of the bottom 40%. The richest 10 percent is almost exclusively white or predominantly European in ancestry. One-third of the population lives under the poverty line, with blacks and other people of color accounting for 70 percent of the poor.[182]

In 2015 United States, African Americans, including multiracial people, earned 76.8% as much as white people. By contrast, black and mixed race Brazilians earned on average 58% as much as whites in 2014.[183] The gap in income between blacks and other non-whites is relatively small compared to the large gap between whites and all people of color. Other social factors, such as illiteracy and education levels, show the same patterns of disadvantage for people of color.[184]

Some commentators[who?] observe that the United States practice of segregation and white supremacy in the South, and discrimination in many areas outside that region, forced many African Americans to unite in the civil rights struggle, whereas the fluid nature of race in Brazil has divided individuals of African ancestry between those with more or less ancestry and helped sustain an image of the country as an example of post-colonial harmony. This has hindered the development of a common identity among black Brazilians.[183]

Though Brazilians of at least partial African heritage make up a large percentage[185] of the population, few blacks have been elected as politicians. The city of Salvador, Bahia, for instance, is 80% people of color, but voters have not elected a mayor of color.

Patterns of discrimination against non-whites have led some academic and other activists to advocate for use of the Portuguese term negro to encompass all African-descended people, in order to stimulate a "black" consciousness and identity.[186]

Afro-Colombians are the third-largest African diaspora population in Latin America after Afro-Brazilians and Afro-Haitians.

Most black Venezuelans descend from people brought as slaves to Venezuela directly from Africa during colonization;[187] others have been descendants of immigrants from the Antilles and Colombia. Many blacks were part of the independence movement, and several managed to be heroes. There is a deep-rooted heritage of African culture in Venezuelan culture, as demonstrated in many traditional Venezuelan music and dances, such as the Tambor, a musical genre inherited from black members of the colony, or the Llanera music or the Gaita zuliana that both are a fusion of all the three major peoples that contribute to the cultural heritage. Also, black inheritance is present in the country's gastronomy.

There are entire communities of blacks in the Barlovento zone, as well as part of the Bolívar state and in other small towns; they also live peaceably among the general population in the rest of Venezuela. Currently, blacks represent a plurality of the Venezuelan population, although many are actually mixed people.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Gorgoryos had already named another concept in Ge'ez[...] (shanqella), which means something like 'negro' in a pejorative sense.

These negroes are the remnants of the original inhabitants of the fluvial region of Somaliland who were overwhelmed by the wave of Somali conquest.[...] The Dube and Shabeli are often referred to as the Adone

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)blasian definition.

{{cite book}}: |work= ignored (help)There are several models for analyzing the marginalization of ethnic minorities. The Afro-Asian population exemplifies Park's definition of marginalization, in that they are the "product of human migrations and socio-cultural conflict." Born into relatively new territory in the area of biracial relations, there entrance into the culture of these Asian states often causes quite a stir. They also fit into Green and Goldberg's definition of psychological marginalization, which constitutes multiple attempts at assimilation with the dominant culture followed by continued rejection. The magazine Ebony, from 1967, outlines a number of Afro-Asians in Japan who find themselves as outcasts, most of which try to find acceptance within the American military bubble, but with varying degrees of success.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Rund eine Million schwarzer Menschen leben laut ISD hierzulande.

In one sense the word 'Moor' means Mohammedan Berbers and Arabs of North-western Africa, with some Syrians, who conquered most of Spain in the 8th century and dominated the country for hundreds of years.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)He is not only the first self-identified African American/person of color to be elected President of the United States—but he is also the first biracial person to hold this office.

This is not to say that race has not been an issue in the campaign. At various stages in the campaign, some commentators have deemed me either "too black" or "not black enough". Racial tensions bubbled to the surface during the week before the South Carolina primary. The press has scoured every exit poll for the latest evidence of racial polarization, not just in terms of white and black, but black and brown as well.See also: video

Barack Obama's real problem isn't that he's too white—it's that he's too black.

For Du Bois, blackness is political, it is existential, but above all, it is moral, for in it values abound; these values spring from the fact of being an oppressed.

In fact, Bill Clinton had promoted an even worse variation, that authentic blackness is political...

The ways of defining blackness range from characteristics of skin tones, hair textures, facial features...

In still other instances, persons are counted in reference to equally ambiguous phenotypical variations, particularly skin color, facial features, or hair texture.

Given the larger numbers of persons of African and indigenous descent in Spanish America, the region developed its own form of eugenics with the concepts of blanqueamiento (whitening) ...blanqueamiento was meant to benefit the entire nation with a white image, and not just individual persons of African descent seeking access to the legal rights and privileges of colonial whites.