Cleveland Guardians — американская профессиональная бейсбольная команда из Кливленда . Guardians соревнуются в Главной лиге бейсбола (MLB) как клуб-член Центрального дивизиона Американской лиги (AL) . С 1994 года команда проводит свои домашние матчи на стадионе Progressive Field (первоначально известном как Jacobs Field в честь тогдашнего владельца команды). С момента своего основания в качестве франшизы Главной лиги в 1901 году команда выиграла 12 титулов Центрального дивизиона, шесть вымпелов Американской лиги и два чемпионата Мировой серии (в 1920 и 1948 годах ). Засуха команды в чемпионатах Мировой серии с 1948 года является самой продолжительной среди всех 30 нынешних команд Главной лиги. [1] Название команды отсылает к Guardians of Traffic , восьми монолитным скульптурам в стиле ар-деко 1932 года работы Генри Геринга на городском Мемориальном мосту Хоуп , [2] который находится рядом с Progressive Field. [3] [4] Талисман команды — «Слайдер». [5] Весенняя тренировочная база команды находится на стадионе Goodyear Ballpark в Гудиере, штат Аризона . [6]

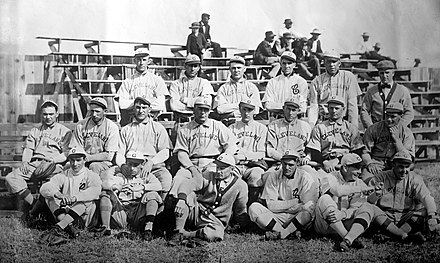

Франшиза возникла в 1894 году как Grand Rapids Rustlers , команда низшей лиги, базирующаяся в Гранд-Рапидс, штат Мичиган , которая играла в Западной лиге . Команда переехала в Кливленд в 1900 году и называлась Cleveland Lake Shores . [7] Сама Западная лига была переименована в Американскую лигу до сезона 1900 года, сохранив при этом свой статус низшей лиги. Когда Американская лига объявила себя высшей лигой в 1901 году, Кливленд был одной из ее восьми чартерных франшиз. Первоначально называвшаяся Cleveland Bluebirds или Blues , команда также неофициально называлась Cleveland Bronchos в 1902 году. Начиная с 1903 года, команда была названа Cleveland Napoleons или Naps , в честь капитана команды и менеджера Напа Лажуа .

Ладжуа ушел после сезона 1914 года , и владелец клуба Чарльз Сомерс попросил бейсбольных журналистов выбрать новое название. Они выбрали название Cleveland Indians . [8] [9] Это название закрепилось и использовалось более века. Распространенными прозвищами для индейцев были «Племя» и «Ваху», последнее отсылало к их давнему логотипу Chief Wahoo . После того, как название индейцев подверглось критике в рамках спора о талисмане коренных американцев , команда приняла название Guardians после сезона 2021 года . [3] [10] [11] [12] [13]

С 24 августа по 14 сентября 2017 года команда одержала 22 победы подряд, что является самой продолжительной победной серией в истории Американской лиги и второй по продолжительности победной серией в истории Главной лиги бейсбола.

По состоянию на конец сезона 2024 года общий показатель франшизы составляет 9852–9369 (.513). [14]

.jpg/440px-Guardian_of_Traffic_(cropped).jpg)

По словам одного историка бейсбола, «В 1857 году бейсбольные матчи были ежедневным зрелищем на площадях Кливленда. Городские власти пытались найти указ, запрещающий это, к радости толпы, но им это не удалось» [15] .

С 1865 по 1868 год Forest Citys был любительским бейсбольным клубом. В сезоне 1869 года Кливленд был среди нескольких городов, которые создали профессиональные бейсбольные команды после успеха Cincinnati Red Stockings 1869 года , первой полностью профессиональной команды. [16] [17] В газетах до и после 1870 года команду часто называли Forest Citys , таким же общим образом, как команду из Чикаго иногда называли The Chicagos.

В 1871 году Forest Citys присоединились к новой Национальной ассоциации профессиональных бейсболистов (NA), первой профессиональной лиге. В конечном итоге, два западных клуба лиги обанкротились в течение первого сезона, а Chicago Fire разорили White Stockings этого города , неспособные снова выставить команду до 1874 года. Таким образом, Кливленд стал самым западным форпостом NA в 1872 году, в год, когда клуб распался. Кливленд играл по полному графику до 19 июля, за которым последовали две игры против Бостона в середине августа, и был расформирован в конце сезона. [18]

В 1876 году Национальная лига (NL) вытеснила NA в качестве главной профессиональной лиги. Кливленд не был среди ее членов-учредителей, но к 1879 году лига искала новых игроков, и город получил команду NL. Были воссозданы новые Cleveland Forest Citys, но к 1882 году они стали известны как Cleveland Blues , потому что Национальная лига требовала различных цветов для этого сезона. Blues имели посредственные результаты в течение шести сезонов и были разрушены торговой войной с Union Association (UA) в 1884 году, когда три ее лучших игрока ( Фред Данлэп , Джек Гласскок и Джим Маккормик ) перешли в UA после того, как им предложили более высокую зарплату. Cleveland Blues объединились с командой UA St. Louis Maroons в 1885 году.

Кливленд оставался без высшей бейсбольной лиги в течение двух сезонов, пока не получил команду в Американской ассоциации (AA) в 1887 году. После того, как Питтсбург Аллегенис из AA перешел в NL, Кливленд последовал его примеру в 1889 году, когда AA начала распадаться. Кливлендский бейсбольный клуб, названный Spiders ( предположительно, вдохновленный их «худыми и тщедушными» игроками), постепенно стал силой в лиге. [19] В 1891 году Spiders переехали в Лиг-Парк , который будет служить домом профессионального бейсбола Кливленда в течение следующих 55 лет. Под руководством уроженца Огайо Сая Янга Spiders стали претендентами в середине 1890-х годов, дважды сыграв в серии Temple Cup (Мировой серии той эпохи) и выиграв ее в 1895 году. После этого успеха команда начала угасать и получила серьезный удар под руководством братьев Робинсон .

Перед сезоном 1899 года Фрэнк Робинсон, владелец «Спайдерс», купил « Сент-Луис Браунс» , таким образом владея двумя клубами одновременно. «Браунс» были переименованы в «Перфектос» и пополнены талантами из Кливленда. Всего за несколько недель до открытия сезона большинство лучших «Спайдерс» были переведены в Сент-Луис, включая трех будущих членов Зала славы: Сая Янга, Джесси Беркетта и Бобби Уоллеса . [20] Маневры в составе не смогли создать мощную команду «Перфектос», поскольку «Сент-Луис» занял пятое место и в 1899, и в 1900 году . «Спайдерс» остались по сути с составом низшей лиги и начали проигрывать игры с рекордной скоростью. Почти не привлекая болельщиков дома, они в конечном итоге играли большую часть своего сезона на выезде и стали известны как «Странники». [21] Команда закончила сезон на 12-м месте, отставая от первого места на 84 игры, с худшим показателем за всю историю 20–134 (процент побед 0,130). [22] После сезона 1899 года Национальная лига расформировала четыре команды, включая франшизу Spiders. Катастрофический сезон 1899 года на самом деле стал шагом к новому будущему для болельщиков Кливленда в следующем году.

Cleveland Infants соревновались в Players' League , которая была хорошо посещаема в некоторых городах, но владельцы клуба не были уверены, что смогут продолжить игру после одного сезона. Cleveland Infants закончили с 55 победами и 75 поражениями, играя свои домашние игры в Brotherhood Park . [23]

Истоки Cleveland Guardians восходят к 1894 году, когда команда была основана как Grand Rapids Rustlers , команда, базирующаяся в Гранд-Рапидс, штат Мичиган , и соревнующаяся в Западной лиге . [7] [24] [25] В 1900 году команда переехала в Кливленд и была названа Cleveland Lake Shores. Примерно в то же время Бан Джонсон изменил название своей низшей лиги (Western League) на American League. В 1900 году Американская лига все еще считалась низшей лигой. В 1901 году команда была названа Cleveland Bluebirds или Blues, когда Американская лига порвала с Национальным соглашением и объявила себя конкурирующей Высшей лигой. Франшиза Cleveland была среди ее восьми членов-учредителей и является одной из четырех команд, которые остаются в своем первоначальном городе, наряду с Boston , Chicago и Detroit .

Новая команда принадлежала угольному магнату Чарльзу Сомерсу и портному Джеку Килфойлу. Сомерс, богатый промышленник и также совладелец Boston Americans , одолжил деньги другим владельцам команд, включая Philadelphia Athletics Конни Мака , чтобы удержать их и новую лигу на плаву. Игроки не считали, что название «Bluebirds» подходит для бейсбольной команды. [26] Писатели часто сокращали его до Cleveland Blues из-за полностью синей формы игроков, [27] но игрокам также не нравилось это неофициальное название. [28] Сами игроки пытались изменить название на Cleveland Bronchos в 1902 году , но это название так и не прижилось. [26]

Кливленд страдал от финансовых проблем в своих первых двух сезонах. Это заставило Сомерса серьезно задуматься о переезде в Питтсбург или Цинциннати . Облегчение пришло в 1902 году в результате конфликта между Национальной и Американской лигами. В 1901 году Наполеон «Нэп» Ладжуа , звездный второй бейсмен Филадельфии Филлис , перешел в A's после того, как его контракт был ограничен 2400 долларами в год — один из самых известных игроков, перешедших в новоиспеченную AL. Впоследствии Филлис подали судебный запрет, чтобы заставить Ладжуа вернуться, который был удовлетворен Верховным судом Пенсильвании . Судебный запрет, казалось, обрекал любые надежды на скорейшее урегулирование между враждующими лигами. Однако адвокат обнаружил, что судебный запрет имел силу только в штате Пенсильвания. [26] Мак, отчасти чтобы поблагодарить Сомерса за его прошлую финансовую поддержку, согласился обменять Лажуа на тогда еще умирающих «Блюз», которые предложили зарплату в размере 25 000 долларов за три года. [29] Однако из-за судебного запрета Лажуа пришлось пропустить все игры против «Эйс» в Филадельфии. [30] Лажуа прибыл в Кливленд 4 июня и сразу же стал хитом, собрав 10 000 болельщиков в Лиг-Парке. Вскоре после этого он был назначен капитаном команды, и в 1903 году команда была названа «Кливлендские Наполеоны» или «Напс» после того, как газета провела конкурс по написанию статей. [26]

Лажуа был назначен менеджером в 1905 году , и удача команды несколько улучшилась. Они закончили на полигры меньше, чем в 1908 году. [31] Однако успех не продлился долго, и Лажуа ушел в отставку в течение сезона 1909 года с поста менеджера, но остался игроком. [32]

После этого команда начала разваливаться, что привело к тому, что Килфойл продал свою долю команды Сомерсу. Сай Янг , вернувшийся в Кливленд в 1909 году, был неэффективен большую часть из трех оставшихся лет [33] , а Эдди Джосс умер от туберкулезного менингита до начала сезона 1911 года. [34]

Несмотря на сильный состав, закреплённый мощными Ладжои и Джо Джексоном , слабая подача удерживала команду ниже третьего места большую часть следующего десятилетия. Один репортер назвал команду «Салфетками», «потому что они так легко сдаются». Команда достигла дна в 1914 и 1915 годах, заняв последнее место оба года. [35] [36]

1915 год принес значительные изменения в команду. Ладжуа, которому было почти 40 лет, больше не был лучшим отбивающим в лиге, отбивая только .258 в 1914 году. Поскольку Ладжуа был вовлечен в конфликт с менеджером Джо Бирмингемом , команда продала Ладжуа обратно в A's. [37]

С уходом Ладжуа клубу нужно было новое название. Сомерс попросил местных бейсбольных журналистов придумать новое название, и на основе их предложений команда была переименована в Cleveland Indians. [38] Название отсылало к прозвищу «индейцы», которое применялось к бейсбольному клубу Cleveland Spiders в то время, когда Луис Сокалексис , коренной американец , играл в Кливленде (1897–1899). [39]

В то же время деловые предприятия Сомерса начали терпеть неудачу, оставив его глубоко в долгах. Поскольку «Индианс» играли плохо, посещаемость и доходы пострадали. [40] Сомерс решил обменять Джексона в середине сезона 1915 года на двух игроков и 31 500 долларов, одну из самых больших сумм, заплаченных за игрока в то время. [41]

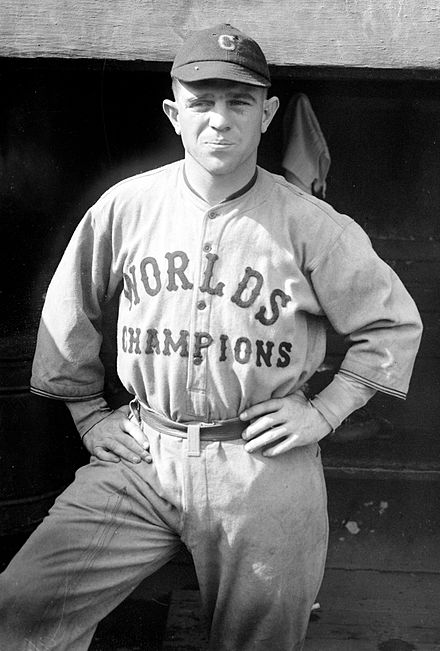

К 1916 году Сомерс был на грани отчаяния и продал команду синдикату во главе с подрядчиком железной дороги Чикаго Джеймсом С. «Джеком» Данном . [40] Менеджер Ли Фол, который занял пост в начале 1915 года, приобрел двух питчеров низшей лиги, Стэна Ковелески и Джима Бэгби , и обменял их на центрального полевого игрока Триса Спикера , который был вовлечён в спор о зарплате с Red Sox . [42] Все трое в конечном итоге стали ключевыми игроками, принесшими Кливленду чемпионство.

Спикер взял бразды правления в свои руки в качестве играющего тренера в 1919 году и привел команду к чемпионству в 1920 году. 16 августа 1920 года «Индианс» играли с « Янкиз» на стадионе «Поло Граундс» в Нью-Йорке. Шортстоп Рэй Чепмен , который часто толпился на площадке, отбивал мяч против Карла Мейса , у которого была необычная подача снизу. К тому же, был уже поздний вечер, и инфилд был полностью затенен, а центральная часть поля (фон отбивающих) была залита солнечным светом. Также в то время «частью работы каждого питчера было пачкать новый мяч в тот момент, когда он был брошен на поле. По очереди они мазали его грязью, лакрицей, табачным соком; его намеренно царапали, шлифовали наждачной бумагой, шрамировали, резали, даже накалывали. В результате получался деформированный, землистого цвета мяч, который хаотично летал по воздуху, имел тенденцию размягчаться в поздних иннингах, и когда он пролетал над пластиной, его было очень трудно увидеть». [43]

В любом случае, Чепмен не двигался рефлекторно, когда подача Мэйса приблизилась к нему. Подача попала Чепмену в голову, сломав ему череп. Чепмен умер на следующий день, став единственным игроком, получившим смертельную травму от поданного мяча. [44] «Индианс», которые в то время были заперты в напряженной трехсторонней гонке за вымпел с «Янкиз» и «Уайт Сокс» , [45] не замедлились из-за смерти своего товарища по команде. Новичок Джо Сьюэлл отбил .329 после замены Чепмена в составе. [46]

В сентябре 1920 года скандал Black Sox достиг своего апогея. Когда до конца сезона оставалось всего несколько игр, а Cleveland и Chicago шли ноздря в ноздрю за первое место со счетом 94–54 и 95–56 соответственно, [47] [48] владелец Chicago отстранил восемь игроков. White Sox проиграли две из трех в своей последней серии, в то время как Cleveland выиграли четыре и проиграли две в своих последних двух сериях. Cleveland закончили на две игры раньше Chicago и на три игры раньше Yankees, чтобы выиграть свой первый вымпел, во главе с 0,388 попаданий Спикера, 30 побед Джима Бэгби и солидной игрой Стива О'Нила и Стэна Ковелески. Cleveland продолжили побеждать Brooklyn Robins со счетом 5–2 в Мировой серии за свой первый титул, выиграв четыре игры подряд после того, как Robins вышли вперед в серии со счетом 2–1. Серия включала три памятных «первых», все они были в пятой игре в Кливленде, и все домашней командой. В первом иннинге правый филдер Элмер Смит выбил первый гранд-слэм серии. В четвертом иннинге Джим Бэгби выбил первый хоумран серии питчером. В верхней части пятого иннинга второй бейсмен Билл Уомбсганс выполнил первый (и единственный, на данный момент) тройной розыгрыш без посторонней помощи в истории Мировой серии, по сути, единственный тройной розыгрыш серии любого рода.

Команда не достигала высот 1920 года в течение 28 лет. Спикер и Ковелески старели, а «Янкиз» поднимались с новым оружием: Бейбом Рутом и хоумраном. Им удалось дважды занять второе место, но большую часть десятилетия они провели на последнем месте. В 1927 году вдова Данна, миссис Джордж Просс (Данн умер в 1922 году), продала команду синдикату во главе с Альвой Брэдли .

К 1930-м годам «Индианс» были посредственной командой, финишировавшей на третьем или четвертом месте в большинстве лет. 1936 год принес Кливленду новую суперзвезду в лице 17-летнего питчера Боба Феллера , который приехал из Айовы с доминирующим фастболом . В том сезоне Феллер установил рекорд, сделав 17 страйкаутов в одной игре, и лидировал в лиге по страйкаутам с 1938 по 1941 год.

20 августа 1938 года кэтчеры «Индианс» Хэнк Хелф и Фрэнк Питлак установили «абсолютный рекорд высоты», поймав бейсбольные мячи, брошенные с 708-футовой (216-метровой) башни Терминала . [49]

К 1940 году Феллер вместе с Кеном Келтнером , Мелом Хардером и Лу Будро привели «Индианс» к одной игре от вымпела. Однако команда была охвачена разногласиями, и некоторые игроки (включая Феллера и Мела Хардера) зашли так далеко, что потребовали, чтобы Брэдли уволил менеджера Осси Витта . Репортеры высмеивали их как «Кливлендских плакс». [50] [ нужен лучший источник ] Феллер, который сделал ноу-хиттер , чтобы открыть сезон, и выиграл 27 игр, проиграл последнюю игру сезона неизвестному питчеру Флойду Гибеллу из « Детройт Тайгерс» . «Тигры» выиграли вымпел, а Гибелл больше никогда не выигрывал в высшей лиге. [51]

Кливленд вошел в 1941 год с молодой командой и новым менеджером; Роджер Пекинпо заменил презираемого Витта; но команда регрессировала, заняв четвертое место. Кливленд вскоре лишился двух звезд. Хэл Троски ушел в отставку в 1941 году из-за мигреней [52] , а Боб Феллер записался на флот через два дня после атаки на Перл-Харбор . Стартовый третий бейсмен Кен Келтнер и аутфилдер Рэй Мэк оба были задрафтованы в 1945 году, забрав еще двух стартовых игроков из состава. [53]

В 1946 году Билл Вик сформировал инвестиционную группу, которая выкупила Cleveland Indians у группы Брэдли за, как сообщалось, 1,6 миллиона долларов. [54] Среди инвесторов были Боб Хоуп , выросший в Кливленде, и бывший отбивающий Tigers Хэнк Гринберг . [55] Бывший владелец франшизы низшей лиги в Милуоки, Вик привез в Кливленд подарок для продвижения. В какой-то момент Вик нанял тренером Макса Паткина с резиновым лицом [56] , «Клоуна-принца бейсбола». Появление Паткина в тренерской ложе было своего рода рекламным трюком, который порадовал фанатов, но разозлил фронт-офис Американской лиги.

Осознав, что он приобрел надежную команду, Вик вскоре покинул стареющий, маленький и неосвещенный Лиг-Парк, чтобы обосноваться на огромном муниципальном стадионе Кливленда . [57] В середине 1932 года «Индианс» ненадолго переехали из Лиг-Парка на муниципальный стадион, но вернулись в Лиг-Парк из-за жалоб на пещеристую среду. Однако с 1937 года «Индианс» начали играть все больше игр на муниципальном стадионе, пока к 1940 году они не сыграли там большую часть своего домашнего состава. [58] Лиг-Парк был в основном снесен в 1951 году, но с тех пор был перестроен в парк отдыха. [59]

Используя по максимуму огромный стадион, Вик установил переносное ограждение в центре поля, которое он мог перемещать внутрь или наружу в зависимости от того, насколько благоприятным было расстояние между индейцами и их противниками в данной серии. Ограждение перемещалось на расстояние до 15 футов (5 м) между противниками серии. После сезона 1947 года Американская лига ответила изменением правил, которое зафиксировало расстояние между стеной внешнего поля на протяжении всего сезона. Однако огромный стадион позволил индейцам установить рекорд на тот момент по количеству зрителей, посмотревших игру Главной бейсбольной лиги. 10 октября 1948 года пятая игра Мировой серии против Boston Braves привлекла более 84 000 зрителей. Рекорд держался до тех пор, пока Los Angeles Dodgers не собрали более 92 500 зрителей, чтобы посмотреть пятую игру Мировой серии 1959 года в Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum против Chicago White Sox .

Под руководством Вика одним из самых значительных достижений Кливленда стало преодоление цветного барьера в Американской лиге , когда он подписал Ларри Доби , бывшего игрока негритянской лиги Newark Eagles в 1947 году , через 11 недель после того, как Джеки Робинсон подписал контракт с Dodgers . [57] Подобно Робинсону, Доби боролся с расизмом на поле и за его пределами, но в 1948 году, в своем первом полном сезоне, показал средний показатель отбивания .301. Мощный центральный филдер, Доби дважды лидировал в Американской лиге по хоумранам.

В 1948 году, нуждаясь в питчере для растянутого забега гонки за вымпел, Вик снова обратился к негритянским лигам и подписал великого питчера Сэтчела Пейджа на фоне множества споров. [57] Отстраненный от участия в Главной лиге бейсбола в расцвете сил, подписание Виком стареющей звезды в 1948 году многими рассматривалось как очередной рекламный трюк. В официальном возрасте 42 лет Пейдж стал самым старым новичком в истории Главной лиги бейсбола и первым чернокожим питчером. Пейдж закончил год с результатом 6–1 с показателем ERA 2,48, 45 страйкаутами и двумя шатаутами. [60]

В 1948 году ветераны Будро, Келтнер и Джо Гордон провели карьерные наступательные сезоны, в то время как новички Доби и Джин Бирден также провели выдающиеся сезоны. Команда дошла до конца с Boston Red Sox , выиграв плей-офф с одной игрой, впервые в истории Американской лиги, чтобы выйти в Мировую серию . В серии Indians победили Boston Braves со счетом 4:2 и стали первыми чемпионами за 28 лет. Будро выиграл награду MVP Американской лиги .

В следующем году «Индианс» появились в фильме под названием «Малыш из Кливленда », в котором Вик проявил интерес. [57] Фильм изображал команду, помогающую «проблемному подростку-фанату» [61] , и в нем участвовали многие члены организации «Индианс». Однако съемки во время сезона стоили игрокам ценных дней отдыха, что привело к усталости к концу сезона. [57] В том сезоне «Кливленд» снова боролся, прежде чем упасть на третье место. 23 сентября 1949 года Билл Вик и «Индианс» закопали свой вымпел 1948 года в центральном поле на следующий день после того, как они были математически исключены из гонки за вымпел. [57]

Позже, в 1949 году, первая жена Вика (которая имела половину доли Вика в команде) развелась с ним. Поскольку большая часть его денег была заморожена в Indians, Вик был вынужден продать команду [62] синдикату, возглавляемому страховым магнатом Эллисом Райаном.

В 1953 году Эл Розен второй год подряд был участником Матча всех звезд, был назван игроком года Главной лиги по версии The Sporting News и выиграл награду «Самый ценный игрок Американской лиги» по единогласному голосованию, играя за «Индианс» после того, как стал лидером АЛ по количеству ранов, хоумранов, RBI (второй год подряд) и проценту слаггинга, а также занял второе место с разницей в одно очко по среднему количеству отбиваний. [63] Райан был вынужден уйти в 1953 году в пользу Майрона Уилсона, который, в свою очередь, уступил место Уильяму Дейли в 1956 году . Несмотря на эту смену владельцев, мощная команда, состоящая из Феллера, Доби, Минни Миньосо , Люка Истера , Бобби Авилы , Эла Розена , Эрли Уинна , Боба Лемона и Майка Гарсии , продолжала бороться до начала 1950-х годов. Однако за десятилетие «Кливленд» выиграл лишь один титул — в 1954 году, пять раз заняв второе место после « Нью-Йорк Янкиз» .

Самый победный сезон в истории франшизы пришелся на 1954 год, когда Indians закончили сезон с результатом 111–43 (.721). Эта отметка установила рекорд Американской лиги по победам, который держался 44 года, пока Yankees не выиграли 114 игр в 1998 году (регулярный сезон из 162 игр). Процент побед Indians 1954 года в .721 до сих пор является рекордом Американской лиги. Indians вернулись в Мировую серию, чтобы встретиться с New York Giants . Однако команда не смогла завоевать титул, в конечном итоге проиграв Giants вчистую. Серия была примечательна тем, что Вилли Мэйс поймал биту Вика Верца через плечо в первой игре. Cleveland оставался талантливой командой на протяжении всего оставшегося десятилетия, заняв второе место в 1959 году, последнем полном году Джорджа Стрикленда в высшей лиге.

С 1960 по 1993 год «Индианс» сумели занять одно третье место (в 1968 году) и шесть четвертых мест (в 1960, 1974, 1975, 1976, 1990 и 1992 годах), но все остальное время провели в нижней части турнирной таблицы или около нее, включая четыре сезона с более чем 100 поражениями (1971, 1985, 1987, 1991).

В 1957 году Indians наняли генерального менеджера Фрэнка Лейна , известного как «Трейдер» Лейн, из St. Louis Cardinals. За эти годы Лейн приобрел репутацию генерального менеджера, который любил заключать сделки. В White Sox Лейн совершил более 100 сделок с участием более 400 игроков за семь лет. [64] За короткое время работы в St. Louis он обменял Реда Шендиенста и Харви Хэддикса . [64] Лейн подытожил свою философию, когда сказал, что единственные сделки, о которых он сожалел, были те, которые он не заключил. [65]

Одной из первых сделок Лейна в Кливленде была отправка Роджера Мариса в Kansas City Athletics в середине 1958 года. Руководитель Indians Хэнк Гринберг был недоволен сделкой [66] , как и Марис, который сказал, что не выносит Лейна. [66] После того, как Марис побил рекорд Бейба Рута по хоумранам, Лейн защищался, говоря, что он все равно заключил бы сделку, потому что Марис был неизвестен, а взамен он получил хороших игроков. [66]

После обмена Мариса Лейн приобрел 25-летнего Норма Кэша из White Sox за Минни Миньосо , а затем обменял его в Детройт, прежде чем тот сыграл хоть одну игру за Indians; Кэш отбил более 350 хоумранов за Tigers. Indians получили Стива Деметера в рамках сделки, который имел всего пять выходов на биту за Cleveland. [67]

В 1960 году Лейн совершил сделку, которая определила его пребывание в Кливленде, когда он обменял правого защитника и любимца публики [68] Рокки Колавито в «Детройт Тайгерс» на Харви Куэнна как раз перед Днем открытия сезона 1960 года .

Это была громкая сделка, в ходе которой со-чемпион Американской лиги 1959 года по хоумранам (Колавито) был обменян на чемпиона Американской лиги по отбиванию (Куэнна). Однако после сделки Колавито четыре раза набрал более 30 хоумранов и трижды попадал в сборную всех звезд за Детройт и Канзас-Сити, прежде чем вернуться в Кливленд в 1965 году . Куэнн, с другой стороны, отыграл за «Индианс» только один сезон, прежде чем отправиться в Сан-Франциско в обмен на стареющих Джонни Антонелли и Вилли Киркланда . Обозреватель журнала Akron Beacon Journal Терри Плуто задокументировал десятилетия горя, последовавшие за сделкой, в своей книге « Проклятие Рокки Колавито» . [69] Несмотря на то, что Колавито был связан с проклятием, он сказал, что никогда не накладывал проклятия на «Индианс», но что сделка была вызвана спором о зарплате с Лейном. [70]

Лейн также организовал уникальную сделку менеджеров в середине сезона 1960 года, отправив Джо Гордона в Tigers в обмен на Джимми Дайкса . Лейн покинул команду в 1961 году, но необдуманные сделки продолжились. В 1965 году Indians обменяли питчера Томми Джона , который выиграл 288 игр за свою карьеру, и Новичка года 1966 года Томми Эйджи в White Sox, чтобы вернуть Колавито. [70]

Однако питчеры Indians установили множество рекордов по страйкаутам. Они лидировали в лиге по количеству K каждый год с 1963 по 1968 год и едва не промахнулись в 1969 году. Команда 1964 года стала первой, кто набрал 1100 страйкаутов, а в 1968 году они стали первой, кто набрал больше страйкаутов, чем позволили хиты.

1970-е годы были не намного лучше: «Индианс» обменяли нескольких будущих звезд, включая Грэйга Неттлза , Денниса Экерсли , Бадди Белла и новичка года 1971 года Криса Чамблисса [71] , на ряд игроков, которые не оказали никакого влияния. [72]

Постоянная смена владельцев не помогла Indians. В 1963 году синдикат Дейли продал команду группе во главе с генеральным менеджером Гейбом Полом . [26] Три года спустя Пол продал Indians Вернону Стоуфферу , [73] из империи замороженных продуктов Стоуффера . До покупки Стоуффером ходили слухи, что команда будет перемещена из-за плохой посещаемости. Несмотря на потенциал для финансово сильного владельца, у Стоуффера были некоторые финансовые неудачи, не связанные с бейсболом, и, как следствие, команда была бедна наличными. Чтобы решить некоторые финансовые проблемы, Стоуффер заключил соглашение сыграть минимум 30 домашних игр в Новом Орлеане с целью возможного переезда туда. [74] Отклонив предложение Джорджа Стейнбреннера и бывшего индейца Эла Розена , Стоуффер продал команду в 1972 году группе во главе с владельцем Cleveland Cavaliers и Cleveland Barons Ником Милети . [74] В 1973 году Штейнбреннер купил команду «Нью-Йорк Янкиз». [75]

Всего пять лет спустя группа Милети продала команду за 11 миллионов долларов синдикату, возглавляемому магнатом грузоперевозок Стивом О'Нилом, в который входил бывший генеральный менеджер и владелец Гейб Пол. [76] Смерть О'Нила в 1983 году привела к тому, что команда снова вышла на рынок. Племянник О'Нила Патрик О'Нил не находил покупателя, пока магнаты недвижимости Ричард и Дэвид Джейкобс не купили команду в 1986 году . [77]

Команда не смогла подняться с последнего места, проиграв сезоны между 1969 и 1975 годами. Одним из ярких моментов стало приобретение Гейлорда Перри в 1972 году . «Индианс» обменяли огненного игрока «Внезапного Сэма» Макдауэлла на Перри, который стал первым питчером-индейцем, выигравшим премию Сая Янга . В 1975 году «Кливленд» сломал еще один цветной барьер, наняв Фрэнка Робинсона в качестве первого афроамериканского менеджера Главной лиги бейсбола. Робинсон был играющим менеджером и стал ярким событием франшизы, когда он выбил хоумран в первый день открытия. Но громкое подписание Уэйна Гарланда , победителя 20 игр в Балтиморе , оказалось катастрофой после того, как Гарланд страдал от проблем с плечом и показал результат 28–48 за пять лет. [78] Команда не смогла улучшиться с Робинсоном в качестве менеджера, и он был уволен в 1977 году . В 1977 году питчер Деннис Экерсли бросил ноу-хиттер против California Angels . В следующем сезоне его обменяли в Boston Red Sox , где он выиграл 20 игр в 1978 году и еще 17 в 1979 году.

В 1970-х годах также прошла печально известная Ten Cent Beer Night на муниципальном стадионе Кливленда. Непродуманная акция в игре 1974 года против Texas Rangers закончилась беспорядками фанатов и поражением Indians. [79]

В 1980-х годах было больше ярких моментов. В мае 1981 года Лен Баркер провел идеальную игру против Toronto Blue Jays , присоединившись к Эдди Джоссу в качестве единственного другого индийского питчера, сделавшего это. [80] «Супер Джо» Шарбоно выиграл награду Американской лиги «Новичок года» . К сожалению, Шарбоно ушел из бейсбола к 1983 году, получив травмы спины [81], а Баркер, которого также беспокоили травмы, так и не стал постоянно доминирующим стартовым питчером. [80]

В конце концов, «Индианс» обменяли Баркера в «Атланта Брэйвз» на Бретта Батлера и Брука Джейкоби , [80] которые стали опорой команды на оставшуюся часть десятилетия. К Батлеру и Джейкоби присоединились Джо Картер , Мел Холл , Хулио Франко и Кори Снайдер , принеся новую надежду болельщикам в конце 1980-х. [82]

Проблемы Кливленда на протяжении 30 лет были освещены в фильме 1989 года « Высшая лига» , в котором комично показан незадачливый бейсбольный клуб Кливленда, который к концу фильма превращается из худшего в лучшего.

В течение 1980-х годов владельцы Indians настаивали на строительстве нового стадиона. Стадион Кливленда был символом славных лет Indians в 1940-х и 1950-х годах. [83] Однако в неурожайные годы даже толпы в 40 000 человек поглощались пещеристой средой. Старый стадион не старел изящно; куски бетона отваливались секциями, а старые деревянные сваи окаменевали. [84] В 1984 году предложение о купольном стадионе стоимостью 150 миллионов долларов было отклонено на референдуме со счетом 2–1. [85]

Наконец, в мае 1990 года избиратели округа Кайахога приняли акцизный налог на продажу алкоголя и сигарет в округе. Налоговые поступления должны были быть использованы для финансирования строительства спортивно-развлекательного комплекса Gateway , который включал бы стадион Jacobs Field для Indians и Gund Arena для баскетбольной команды Cleveland Cavaliers . [86]

Удача команды начала меняться в 1989 году , по иронии судьбы, с очень непопулярной торговли. Команда отправила мощного аутфилдера Джо Картера в San Diego Padres за двух непроверенных игроков, Сэнди Аломара-младшего и Карлоса Баергу . Аломар оказал немедленное влияние, не только будучи избранным в команду всех звезд , но и выиграв четвертую награду «Новичок года» Кливленда и « Золотую перчатку» . Баерга стал трехкратным участником матча всех звезд с постоянной результативностью в нападении.

Генеральный менеджер Indians Джон Харт сделал ряд ходов, которые в конечном итоге принесли успех команде. В 1991 году он нанял бывшего Indian Майка Харгроува в качестве менеджера и обменял кэтчера Эдди Таубенси в Houston Astros , которые, имея избыток аутфилдеров, были готовы расстаться с Кенни Лофтоном . Лофтон занял второе место в голосовании за Новичка года AL со средним показателем .285 и 66 украденными базами .

В 1992 году журнал Baseball America [87] назвал «Индианс» «Организацией года» в ответ на появление ярких моментов в нападении и улучшение системы фермерства .

The team suffered a tragedy during spring training of 1993, when a boat carrying pitchers Steve Olin, Tim Crews, and Bob Ojeda crashed into a pier. Olin and Crews were killed, and Ojeda was seriously injured. (Ojeda missed most of the season, and retired the following year).[88]

By the end of the 1993 season, the team was in transition, leaving Cleveland Stadium and fielding a talented nucleus of young players. Many of those players came from the Indians' new AAA farm team, the Charlotte Knights, who won the International League title that year.

Indians General Manager John Hart and team owner Richard Jacobs managed to turn the team's fortunes around. The Indians opened Jacobs Field in 1994 with the aim of improving on the prior season's sixth-place finish. The Indians were only one game behind the division-leading Chicago White Sox on August 12 when a players strike wiped out the rest of the season.

Having contended for the division in the aborted 1994 season, Cleveland sprinted to a 100–44 record (the season was shortened by 18 games due to player/owner negotiations) in 1995, winning its first-ever divisional title. Veterans Dennis Martínez, Orel Hershiser and Eddie Murray combined with a young core of players including Omar Vizquel, Albert Belle, Jim Thome, Manny Ramírez, Kenny Lofton and Charles Nagy to lead the league in team batting average as well as team ERA.

After defeating the Boston Red Sox in the Division Series and the Seattle Mariners in the ALCS, Cleveland clinched the American League pennant and a World Series berth, for the first time since 1954. The World Series ended in disappointment, however: the Indians fell in six games to the Atlanta Braves.

Tickets for every Indians home game sold out several months before opening day in 1996.[89] The Indians repeated as AL Central champions but lost to the wild card Baltimore Orioles in the Division Series.

In 1997, Cleveland started slow but finished with an 86–75 record. Taking their third consecutive AL Central title, the Indians defeated the New York Yankees in the Division Series, 3–2. After defeating the Baltimore Orioles in the ALCS, Cleveland went on to face the Florida Marlins in the World Series that featured the coldest game in World Series history. With the series tied after Game 6, the Indians went into the ninth inning of Game Seven with a 2–1 lead, but closer José Mesa allowed the Marlins to tie the game. In the eleventh inning, Édgar Rentería drove in the winning run giving the Marlins their first championship. Cleveland became the first team to lose the World Series after carrying the lead into the ninth inning of the seventh game.

In 1998, the Indians made the postseason for the fourth straight year. After defeating the wild-card Boston Red Sox 3–1 in the Division Series, Cleveland lost the 1998 ALCS in six games to the New York Yankees, who had come into the postseason with a then-AL record 114 wins in the regular season.[90]

For the 1999 season, Cleveland added relief pitcher Ricardo Rincón and second baseman Roberto Alomar, brother of catcher Sandy Alomar Jr.,[91] and won the Central Division title for the fifth consecutive year. The team scored 1,009 runs, becoming the first (and to date only) team since the 1950 Boston Red Sox to score more than 1,000 runs in a season. This time, Cleveland did not make it past the first round, losing the Division Series to the Red Sox, despite taking a 2–0 lead in the series. In game three, Indians starter Dave Burba went down with an injury in the 4th inning.[92] Four pitchers, including presumed game four starter Jaret Wright, surrendered nine runs in relief. Without a long reliever or emergency starter on the playoff roster, Hargrove started both Bartolo Colón and Charles Nagy in games four and five on only three days rest.[92] The Indians lost game four 23–7 and game five 12–8.[93] Four days later, Hargrove was dismissed as manager.[94]

In 2000, the Indians had a 44–42 start, but caught fire after the All Star break and went 46–30 the rest of the way to finish 90–72.[95] The team had one of the league's best offenses that year and a defense that yielded three gold gloves. However, they ended up five games behind the Chicago White Sox in the Central division and missed the wild card by one game to the Seattle Mariners. Mid-season trades brought Bob Wickman and Jake Westbrook to Cleveland. After the season, free-agent outfielder Manny Ramírez departed for the Boston Red Sox.

In 2000, Larry Dolan bought the Indians for $320 million from Richard Jacobs, who, along with his late brother David, had paid $45 million for the club in 1986. The sale set a record at the time for the sale of a baseball franchise.[96]

2001 saw a return to the postseason. After the departures of Ramírez and Sandy Alomar Jr., the Indians signed Ellis Burks and former MVP Juan González, who helped the team win the Central division with a 91–71 record. One of the highlights came on August 5, when the Indians completed the biggest comeback in MLB History. Cleveland rallied to close a 14–2 deficit in the seventh inning to defeat the Seattle Mariners 15–14 in 11 innings. The Mariners, who won an MLB record-tying 116 games that season, had a strong bullpen, and Indians manager Charlie Manuel had already pulled many of his starters with the game seemingly out of reach.

Seattle and Cleveland met in the first round of the postseason; however, the Mariners won the series 3–2. In the 2001–02 offseason, GM John Hart resigned and his assistant, Mark Shapiro, took the reins.

Shapiro moved to rebuild by dealing aging veterans for younger talent. He traded Roberto Alomar to the New York Mets for a package that included outfielder Matt Lawton and prospects Alex Escobar and Billy Traber. When the team fell out of contention in mid-2002, Shapiro fired manager Charlie Manuel and traded pitching ace Bartolo Colón for prospects Brandon Phillips, Cliff Lee, and Grady Sizemore; acquired Travis Hafner from the Rangers for Ryan Drese and Einar Díaz; and picked up Coco Crisp from the St. Louis Cardinals for aging starter Chuck Finley. Jim Thome left after the season, going to the Phillies for a larger contract.

Young Indians teams finished far out of contention in 2002 and 2003 under new manager Eric Wedge. They posted strong offensive numbers in 2004, but continued to struggle with a bullpen that blew more than 20 saves. A highlight of the season was a 22–0 victory over the New York Yankees on August 31, one of the worst defeats suffered by the Yankees in team history.[97]

In early 2005, the offense got off to a poor start. After a brief July slump, the Indians caught fire in August, and cut a 15.5 game deficit in the Central Division down to 1.5 games. However, the season came to an end as the Indians went on to lose six of their last seven games, five of them by one run, missing the playoffs by only two games. Shapiro was named Executive of the Year in 2005.[98] The next season, the club made several roster changes, while retaining its nucleus of young players. The off-season was highlighted by the acquisition of top prospect Andy Marte from the Boston Red Sox. The Indians had a solid offensive season, led by career years from Travis Hafner and Grady Sizemore. Hafner, despite missing the last month of the season, tied the single season grand slam record of six, which was set in 1987 by Don Mattingly.[99] Despite the solid offensive performance, the bullpen struggled with 23 blown saves (a Major League worst), and the Indians finished a disappointing fourth.[100]

In 2007, Shapiro signed veteran help for the bullpen and outfield in the offseason. Veterans Aaron Fultz and Joe Borowski joined Rafael Betancourt in the Indians bullpen.[101] The Indians improved significantly over the prior year and went into the All-Star break in second place. The team brought back Kenny Lofton for his third stint with the team in late July.[102] The Indians finished with a 96–66 record tied with the Red Sox for best in baseball, their seventh Central Division title in 13 years and their first postseason trip since 2001.[103]

The Indians began their playoff run by defeating the Yankees in the ALDS three games to one. This series will be most remembered for the swarm of bugs that overtook the field in the later innings of Game Two. They also jumped out to a three-games-to-one lead over the Red Sox in the ALCS. The season ended in disappointment when Boston swept the final three games to advance to the 2007 World Series.[103]

Despite the loss, Cleveland players took home a number of awards. Grady Sizemore, who had a .995 fielding percentage and only two errors in 405 chances, won the Gold Glove award, Cleveland's first since 2001.[104] Indians Pitcher CC Sabathia won the second Cy Young Award in team history with a 19–7 record, a 3.21 ERA and an MLB-leading 241 innings pitched.[105] Eric Wedge was awarded the first Manager of the Year Award in team history.[106] Shapiro was named to his second Executive of the Year in 2007.[98]

The Indians struggled during the 2008 season. Injuries to sluggers Travis Hafner and Victor Martinez, as well as starting pitchers Jake Westbrook and Fausto Carmona led to a poor start.[107] The Indians, falling to last place for a short time in June and July, traded CC Sabathia to the Milwaukee Brewers for prospects Matt LaPorta, Rob Bryson, and Michael Brantley.[108] and traded starting third baseman Casey Blake for catching prospect Carlos Santana.[109] Pitcher Cliff Lee went 22–3 with an ERA of 2.54 and earned the AL Cy Young Award.[110] Grady Sizemore had a career year, winning a Gold Glove Award and a Silver Slugger Award,[111] and the Indians finished with a record of 81–81.

Prospects for the 2009 season dimmed early when the Indians ended May with a record of 22–30. Shapiro made multiple trades: Cliff Lee and Ben Francisco to the Philadelphia Phillies for prospects Jason Knapp, Carlos Carrasco, Jason Donald and Lou Marson; Victor Martinez to the Boston Red Sox for prospects Bryan Price, Nick Hagadone and Justin Masterson; Ryan Garko to the Texas Rangers for Scott Barnes; and Kelly Shoppach to the Tampa Bay Rays for Mitch Talbot. The Indians finished the season tied for fourth in their division, with a record of 65–97. The team announced on September 30, 2009, that Eric Wedge and all of the team's coaching staff were released at the end of the 2009 season.[112] Manny Acta was hired as the team's 40th manager on October 25, 2009.[113]

On February 18, 2010, it was announced that Shapiro (following the end of the 2010 season) would be promoted to team President, with current President Paul Dolan becoming the new Chairman/CEO, and longtime Shapiro assistant Chris Antonetti filling the GM role.[114]

_2017-01-27_(cropped).jpg/440px-Mike_Chernoff_(baseball)_2017-01-27_(cropped).jpg)

On January 18, 2011, longtime popular former first baseman and manager Mike Hargrove was brought in as a special adviser. The Indians started the 2011 season strong – going 30–15 in their first 45 games and seven games ahead of the Detroit Tigers for first place. Injuries led to a slump where the Indians fell out of first place. Many minor leaguers such as Jason Kipnis and Lonnie Chisenhall got opportunities to fill in for the injuries.[115] The biggest news of the season came on July 30 when the Indians traded four prospects for Colorado Rockies star pitcher, Ubaldo Jiménez. The Indians sent their top two pitchers in the minors, Alex White and Drew Pomeranz along with Joe Gardner and Matt McBride.[116] On August 25, the Indians signed the team leader in home runs, Jim Thome off of waivers.[117] He made his first appearance in an Indians uniform since he left Cleveland after the 2002 season. To honor Thome, the Indians placed him at his original position, third base, for one pitch against the Minnesota Twins on September 25. It was his first appearance at third base since 1996, and his last for Cleveland.[118] The Indians finished the season in 2nd place, 15 games behind the division champion Tigers.[119]

The Indians broke Progressive Field's Opening Day attendance record with 43,190 against the Toronto Blue Jays on April 5, 2012. The game went 16 innings, setting the MLB Opening Day record, and lasted 5 hours and 14 minutes.[120]

On September 27, 2012, with six games left in the Indians' 2012 season, Manny Acta was fired; Sandy Alomar Jr. was named interim manager for the remainder of the season.[121] On October 6, the Indians announced that Terry Francona, who managed the Boston Red Sox to five playoff appearances and two World Series between 2004 and 2011, would take over as manager for 2013.[122]

The Indians entered the 2013 season following an active offseason of dramatic roster turnover. Key acquisitions included free agent 1B/OF Nick Swisher and CF Michael Bourn.[123] The team added prized right-handed pitching prospect Trevor Bauer, OF Drew Stubbs, and relief pitchers Bryan Shaw and Matt Albers in a three-way trade with the Arizona Diamondbacks and Cincinnati Reds that sent RF Shin-Soo Choo to the Reds, and Tony Sipp to the Arizona Diamondbacks[124] Other notable additions included utility man Mike Avilés, catcher Yan Gomes, designated hitter Jason Giambi, and starting pitcher Scott Kazmir.[123][125] The 2013 Indians increased their win total by 24 over 2012 (from 68 to 92), finishing in second place, one game behind Detroit in the Central division, but securing the number one seed in the American League Wild Card Standings. In their first postseason appearance since 2007, Cleveland lost the 2013 American League Wild Card Game 4–0 at home to Tampa Bay. Francona was recognized for the turnaround with the 2013 American League Manager of the Year Award.

With an 85–77 record, the 2014 Indians had consecutive winning seasons for the first time since 1999–2001, but they were eliminated from playoff contention during the last week of the season and finished third in the AL Central.

.jpg/440px-Shane_Bieber_February_1,_2020_(49488948046).jpg)

In 2015, after struggling through the first half of the season, the Indians finished 81–80 for their third consecutive winning season, which the team had not done since 1999–2001. For the second straight year, the Tribe finished third in the Central and was eliminated from the Wild Card race during the last week of the season. Following the departure of longtime team executive Mark Shapiro on October 6, the Indians promoted GM Chris Antonetti to President of Baseball Operations, assistant general manager Mike Chernoff to GM, and named Derek Falvey as assistant GM.[126] Falvey was later hired by the Minnesota Twins in 2016, becoming their President of Baseball Operations.

The Indians set what was then a franchise record for longest winning streak when they won their 14th consecutive game, a 2–1 win over the Toronto Blue Jays in 19 innings on July 1, 2016, at Rogers Centre.[127][128] The team clinched the Central Division pennant on September 26, their eighth division title overall and first since 2007, as well as returning to the playoffs for the first time since 2013. They finished the regular season at 94–67, marking their fourth straight winning season, a feat not accomplished since the 1990s and early 2000s.

The Indians began the 2016 postseason by sweeping the Boston Red Sox in the best-of-five American League Division Series, then defeated the Blue Jays in five games in the 2016 American League Championship Series to claim their sixth American League pennant and advance to the World Series against the Chicago Cubs. It marked the first appearance for the Indians in the World Series since 1997 and first for the Cubs since 1945. The Indians took a 3–1 series lead following a victory in Game 4 at Wrigley Field, but the Cubs rallied to take the final three games and won the series 4 games to 3. The Indians' 2016 success led to Francona winning his second AL Manager of the Year Award with the club.

From August 24 through September 15 during the 2017 season, the Indians set a new American League record by winning 22 games in a row.[129] On September 28, the Indians won their 100th game of the season, marking only the third time in history the team has reached that milestone. They finished the regular season with 102 wins, second-most in team history (behind 1954's 111 win team). The Indians earned the AL Central title for the second consecutive year, along with home-field advantage throughout the American League playoffs, but they lost the 2017 ALDS to the Yankees 3–2 after being up 2–0.[130]

In 2018, the Indians won their third consecutive AL Central crown with a 91–71 record, but were swept in the 2018 American League Division Series by the Houston Astros, who outscored Cleveland 21–6. In 2019, despite a two-game improvement, the Indians missed the playoffs as they trailed three games behind the Tampa Bay Rays for the second AL Wild Card berth. During the 2020 season (shortened to 60 games because of the COVID-19 pandemic), the Indians were 35–25, finishing second behind the Minnesota Twins in the AL Central, but qualified for the expanded playoffs. In the best-of-three AL Wild Card Series, the Indians were swept by the New York Yankees, ending their season.

On December 18, 2020, the team announced that the Indians name and logo would be dropped after the 2021 season, later revealing the replacement to be the Guardians.[131][12][3][13] In their first season as the Guardians, the team won the 2022 AL Central Division crown, marking the 11th division title in franchise history. In the best-of-three AL Wild Card Series, the Guardians won the series against the Tampa Bay Rays 2–0, to advance to the AL Division Series. The Guardians lost the series to the New York Yankees 3–2, ending their season. In June 2022, sports investor David Blitzer bought a 25% stake in the franchise with an option to acquire controlling interest in 2028.[132][133]

.jpg/440px-Stephen_Vogt_(53479720675).jpg)

Following Francona's retirement at the end of the 2023 season, the Guardians named Stephen Vogt as their new manager on November 6, 2023.

The rivalry with fellow Ohio team the Cincinnati Reds is known as the Battle of Ohio or Buckeye Series and features the Ohio Cup trophy for the winner. Prior to 1997, the winner of the cup was determined by an annual pre-season baseball game, played each year at minor-league Cooper Stadium in the state capital of Columbus, and staged just days before the start of each new Major League Baseball season. A total of eight Ohio Cup games were played, with the Guardians winning six of them. It ended with the start of interleague play in 1997. The winner of the game each year was awarded the Ohio Cup in postgame ceremonies. The Ohio Cup was a favorite among baseball fans in Columbus, with attendances regularly topping 15,000.

Since 1997, the two teams have played each other as part of the regular season, with the exception of 2002. The Ohio Cup was reintroduced in 2008 and is presented to the team who wins the most games in the series that season. Initially, the teams played one three-game series per season, meeting in Cleveland in 1997 and Cincinnati the following year. The teams have played two series per season against each other since 1999, with the exception of 2002, one at each ballpark. A format change in 2013 made each series two games, except in years when the AL and NL Central divisions meet in interleague play, where it is usually extended to three games per series.[134] As of 2024, the Guardians lead the series 76-59.[135]

An on-and-off rivalry with the Pittsburgh Pirates stems from the close proximity of the two cities, and features some carryover elements from the longstanding rivalry in the National Football League between the Cleveland Browns and Pittsburgh Steelers. Because the Guardians' designated interleague rival is the Reds and the Pirates' designated rival is the Tigers, the teams have played periodically. The teams played one three-game series each year from 1997 to 2001 and periodically between 2002 and 2022, generally only in years in which the AL Central played the NL Central in the former interleague play rotation. The teams played six games in 2020 as MLB instituted an abbreviated schedule focusing on regional match-ups. Beginning in 2023, the teams will play a three-game series each season as a result of the new "balanced" schedule. The Pirates lead the series 21–18.[136]

As the Guardians play most of their games every year with each of their AL Central competitors (formerly 19 for each team until 2023), several rivalries have developed.

The Guardians have a geographic rivalry with the Detroit Tigers, highlighted in past years by intense battles for the AL Central title. The matchup has some carryover elements from the Ohio State-Michigan rivalry, as well as the general historic rivalry between Michigan and Ohio dating back to the Toledo War.

The Chicago White Sox are another rival, dating back to the 1959 season, when the Sox slipped past the Indians to win the AL pennant. The rivalry intensified when both clubs were moved to the newly created AL Central in 1994. During that season, the two teams challenged for the division title, with the Indians one game back of Chicago when the season ended in August due to the players' strike. During a game in Chicago, the White Sox confiscated Albert Belle's corked bat, followed by an attempt by Indians pitcher Jason Grimsley to crawl through the Comiskey Park clubhouse ceiling to retrieve it. Belle later signed with the White Sox in 1997, adding additional intensity to the rivalry. In 2005, the White Sox led the division by 15 games in July, only to see the Indians trim the lead to a single game late in the season. However, the White Sox swept a three-game series to end the season to win the division by six games; the Sox later won that year's World Series.

On August 5, 2023, Cleveland third baseman José Ramírez and Chicago shortstop Tim Anderson instigated a bench-clearing brawl after Anderson applied a tag to Ramírez. Anderson then attempted to punch Ramírez, after which Ramírez wound up up knocking Anderson to the ground with a right hook. Anderson and Ramírez were suspended five and two games, respectively, for their roles in the brawl.

The official team colors are navy blue, red, and white.[137][138][139]

The primary home uniform is white with navy blue piping around each sleeve. Across the front of the jersey in script font is the word "Guardians" in red with a navy blue outline, with navy blue undershirts, belts, and socks.

The alternate home jersey is red with a navy blue script "Guardians" trimmed in white on the front, and navy blue piping on both sleeves, with navy blue undershirts, belts, and socks.[140]

In 2024, the team introduced "City Connect" uniforms, primarily (but not exclusively) worn on Friday home dates. The jerseys are blue with red and white stripes going down the sleeve, featuring "CLE" on the front of the jersey and the player names and numbers on the back (all in a white art deco style font), with sandstone colored pants and red socks featuring a logo which was also introduced in 2024 (a "Guardians of Traffic" statue holding a baseball bat).[141]

The standard home cap is navy blue with a red bill, features a red "diamond C" on the front and is worn with both the primary white and alternate red jerseys. The "City Connect" home cap is similar to the standard cap with the exception of the front section over the bill being white.

The primary road uniform is gray, with "Cleveland" in navy blue "diamond C" letters, trimmed in red across the front of the jersey, navy blue piping around the sleeves, and navy blue undershirts, belts, and socks.

The alternate road jersey is navy blue with "Cleveland" in red "diamond C" letters trimmed in white on the front of the jersey, and navy blue undershirts, belts, and socks.

The road cap is similar to the home cap, with the difference being the bill is navy blue.

For all games, the team uses a navy blue batting helmet with a red "diamond C" on the front.[142]

All jerseys (sans the "City Connect" version) feature the "winged G" logo on one sleeve, and every jersey has a patch from Marathon Petroleum – in a sponsorship deal lasting through the 2026 season – on the other. The sleeve featuring the Marathon logo depends on how the player bats – left handed hitters have it on their right sleeve, as that is the arm facing the main TV camera when he bats, and vice versa for right handed batters.[143]

The club name and its cartoon logo have been criticized for perpetuating Native American stereotypes. In 1997 and 1998, protesters were arrested after effigies were burned. Charges were dismissed in the 1997 case, and were not filed in the 1998 case. Protesters arrested in the 1998 incident subsequently fought and lost a lawsuit alleging that their First Amendment rights had been violated.[144][145][146][147]

Bud Selig (then-Commissioner of Baseball) said in 2014 that he had never received a complaint about the logo. He has heard that there are some protesting against the mascots, but individual teams such as the Indians and Atlanta Braves, whose name was also criticized for similar reasons, should make their own decisions.[148] An organized group consisting of Native Americans, which had protested for many years, protested Chief Wahoo on Opening Day 2015, noting that this was the 100th anniversary since the team became the Indians. Owner Paul Dolan, while stating his respect for the critics, said he mainly heard from fans who wanted to keep Chief Wahoo, and had no plans to change.[149]

On January 29, 2018, Major League Baseball announced that Chief Wahoo would be removed from the Indians' uniforms as of the 2019 season, stating that the logo was no longer appropriate for on-field use.[150][151] The block "C" was promoted to the primary logo; at the time, there were no plans to change the team's name.[152]

In 2020, protests over the murder of George Floyd, a black man, by a Minneapolis police officer, led the United States into a period of social changes. This made Dolan to reconsider use of the Indians name.[153][154] On July 3, 2020, on the heels of the Washington Redskins announcing that they would "undergo a thorough review" of that team's name, the Indians announced that they would "determine the best path forward" regarding the team's name and emphasized the need to "keep improving as an organization on issues of social justice".[155]

On December 13, 2020, it was reported that the Indians name would be dropped after the 2021 season out of respect for the Native American community.[156][157] Although it had been hinted by the team that they may move forward without a replacement name (in a similar manner to the Washington Football Team, which used its name for 2 years until being named the Washington Commanders).[156][158] It was announced via Twitter on July 23, 2021, that the team will be named the Guardians, after the Guardians of Traffic, eight large Art Deco statues on the Hope Memorial Bridge, located close to Progressive Field.[159]

The club, however, found itself amid a trademark dispute with a men's roller derby team called the Cleveland Guardians.[160][161][162] The Cleveland Guardians roller derby team has competed in the Men's Roller Derby Association since 2016.[163] In addition, two other entities have attempted to preempt the team's use of the trademark by filing their own registrations with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.[160] The roller derby team filed a federal lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio on October 27, 2021, seeking to block the baseball team's name change.[164][165][166] On November 16, 2021, the lawsuit was resolved, and both teams were allowed to continue using the Guardians name. The name change from Indians to Guardians became official on November 19, 2021.[167][168][10][11][12][3][13]

iHeart Media Cleveland sister stations WTAM (1100 AM/106.9 FM) and WMMS (100.7 FM) serve as the flagship stations for the Cleveland Guardians Radio Network,[169] with lead announcer Tom Hamilton and Jim Rosenhaus calling the games.[170]

Fellow sister station WARF (1350 AM) - while primarily an English language station - airs Spanish broadcasts of home games, complimenting the flagship coverage. Rafa Hernández-Brito serves as the primary Spanish announcer, alongside analyst and former Indian Carlos Baerga (Octavio Sequera fills in when Brito calls Cleveland Cavaliers Spanish radio broadcasts).[171]

The television rights are held by Bally Sports Great Lakes. Lead announcer Matt Underwood, analyst and former Indians Gold Glove-winning centerfielder Rick Manning, and field reporter Andre Knott form the broadcast team, with Al Pawlowski and former Indians pitcher Jensen Lewis serving as pregame and postgame hosts. Former Indians Pat Tabler and Chris Gimenez serve as contributors and periodic fill-ins for Manning and Lewis.[170][172] Select games are simulcast over-the-air on WKYC channel 3.[173]

Notable former broadcasters include Tom Manning, Jack Graney (the first ex-baseball player to become a play-by-play announcer), Ken Coleman, Joe Castiglione, Van Patrick, Nev Chandler, Bruce Drennan, Jim "Mudcat" Grant, Rocky Colavito, Dan Coughlin, and Jim Donovan.

Previous broadcasters who have had lengthy tenures with the team include Joe Tait (15 seasons between TV and radio), Jack Corrigan (18 seasons on TV), Ford C. Frick Award winner Jimmy Dudley (19 seasons on radio), Mike Hegan (23 seasons between TV and radio), and Herb Score (34 seasons between TV and radio).[174]

Under the Cleveland Indians name, the team has been featured in several films, including:

.jpg/440px-Jim_Thome_(18421174923).jpg)

Numerous Naps/Indians players have had statues made in their honor:

(*) – Inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame as an Indian/Nap.

In July 2022 - in honor of the 75th anniversary of Larry Doby becoming the AL's first black player - a mural was added to the exterior of Progressive Field, honoring players who were viewed as barrier breakers that played for the Indians/Guardians. The mural features Doby, Frank Robinson, and Satchel Paige.[179]

A portion of Eagle Avenue near Progressive Field was renamed "Larry Doby Way" in 2012[180]

A number of parks and newly built and renovated youth baseball fields in Cleveland have been named after former and current Indians/Guardians players, including:

The Cleveland Guardians farm system consists of seven minor league affiliates.[185]

(*) - There were no fans allowed in any MLB stadium in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

(**) - At the beginning of the season, there was a limit of 30% capacity due to COVID-19 restrictions implemented by Ohio Governor Mike DeWine. On June 2, DeWine lifted the restrictions, and the team immediately allowed full capacity at Progressive Field.

So, with the Cubs finally on top, the longest championship drought in baseball now belongs to the team they beat – the Indians. Cleveland has not won a World Series since way back in 1948.

The AL outfit originated as a Western League team known as the Grand Rapids Rustlers, then the Cleveland Lakeshores.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)The official logo of the 2019 All-Star Game celebrates the rich culture of Cleveland. Here in the spiritual birthplace of Rock and Roll, baseball and music are brought together through the icon of a guitar. Baseball stitching creates the shape that hold the "Rock and Roll" stylized letters of the All-Star Game and its host. The MLB logo punctuates this stylized representation as the head of the guitar. The Club's colors of red and blue are joined with tones of gray used for depth and dimension, while the six strings of the guitar are cleverly used in theme art to recognize Cleveland's sixth time hosting the Midsummer Classic.

We will maintain the red, white and navy color scheme that has been part of our organization for more than 80 years to honor our rich baseball heritage.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)According to the MLB site, the Cleveland Indians may consider a new logo in the future, but will promote the capital letter C for now. There are no current plans to change the Indians' team name.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) (Plain Dealer)