Лос-Анджелес , [a] часто упоминаемый по его инициалам LA , является самым густонаселенным городом в американском штате Калифорния . С предполагаемым населением 3 820 914 жителей в пределах города по состоянию на 2023 год , [8] это второй по численности населения город в Соединенных Штатах, уступая только Нью-Йорку ; он также является коммерческим, финансовым и культурным центром Южной Калифорнии . Лос-Анджелес имеет этнически и культурно разнообразное население и является главным городом столичного района с населением 12,8 миллиона человек (2023). Большой Лос-Анджелес , который включает столичные районы Лос-Анджелеса и Риверсайд-Сан-Бернардино , является обширным мегаполисом с населением более 18,3 миллиона человек.[update]

Большая часть города расположена в бассейне в Южной Калифорнии, прилегающем к Тихому океану на западе и простирающемся частично через горы Санта-Моника и на север в долину Сан-Фернандо , при этом город граничит с долиной Сан-Габриэль на востоке. Он охватывает около 469 квадратных миль (1210 км 2 ), [6] и является административным центром округа Лос-Анджелес , который является самым густонаселенным округом в Соединенных Штатах с предполагаемым населением 9,86 миллиона человек по состоянию на 2022 год [update]. [17] Это четвертый по посещаемости город в США с более чем 2,7 миллионами посетителей по состоянию на 2022 год. [18]

Территория, которая стала Лос-Анджелесом, изначально была заселена коренным народом тонгва , а позже Хуан Родригес Кабрильо заявил права на нее Испании в 1542 году. Город был основан 4 сентября 1781 года испанским губернатором Фелипе де Неве в деревне Яанга . [19] Он стал частью Мексики в 1821 году после Мексиканской войны за независимость . В 1848 году, по окончании Мексиканско-американской войны , Лос-Анджелес и остальная часть Калифорнии были куплены в рамках Договора Гваделупе-Идальго и стали частью Соединенных Штатов. Лос-Анджелес был включен в качестве муниципалитета 4 апреля 1850 года, за пять месяцев до того, как Калифорния получила статус штата . Открытие нефти в 1890-х годах привело к быстрому росту города. [20] Город был еще больше расширен с завершением строительства акведука Лос-Анджелеса в 1913 году, который доставляет воду из Восточной Калифорнии .

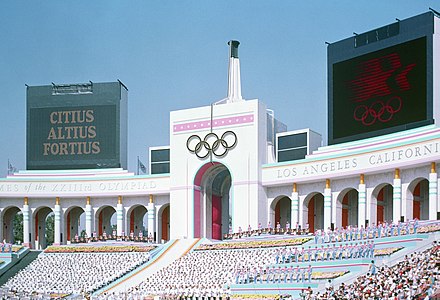

Лос-Анджелес имеет разнообразную экономику с широким спектром отраслей. Несмотря на резкий отток кино- и телепроизводства после пандемии COVID-19 , [21] Лос-Анджелес по-прежнему является одним из крупнейших центров американского кинопроизводства , [22] [23] крупнейшим в мире по доходам; город является важным местом в истории кино . Он также имеет один из самых загруженных контейнерных портов в Америке. [24] [25] [26] В 2018 году валовой продукт агломерации Лос-Анджелеса составил более 1,0 триллиона долларов, [27] что сделало его городом с третьим по величине ВВП в мире после Нью-Йорка и Токио . Лос-Анджелес принимал летние Олимпийские игры в 1932 и 1984 годах , а также примет их в 2028 году . Несмотря на отток бизнеса из центра Лос-Анджелеса после пандемии COVID-19 , городское ядро развивается как культурный центр с крупнейшей в мире выставкой архитектуры, спроектированной Фрэнком Гери . [28]

4 сентября 1781 года группа из 44 поселенцев, известных как « Лос Побладорес », основала пуэбло (город), который они назвали Эль-Пуэбло-де-Нуэстра-Сеньора-ла-Рейна-де-лос-Анхелес , «Город Богоматери , Королевы ангелов». [29] Первоначальное название поселения оспаривается; В Книге рекордов Гиннеса он указан как «Эль-Пуэбло де Нуэстра-Сеньора ла Королева де лос Анхелес де Порсьункула »; [30] в других источниках есть сокращенные или альтернативные версии более длинного имени. [31]

Местное английское произношение названия города со временем менялось. В статье 1953 года в журнале Американского общества названий утверждается, что произношение / l ɔː s ˈ æ n dʒ əl ə s / lawss AN -jəl-əs установилось после включения города в состав США в 1850 году, а с 1880-х годов произношение / l oʊ s ˈ æ ŋ ɡ əl ə s / lohss ANG -gəl-əs возникло из-за тенденции в Калифорнии давать местам испанские или звучащие по-испански названия и произношения. [32] В 1908 году библиотекарь Чарльз Флетчер Ламмис , выступавший за произношение имени с твёрдым g ( / ɡ / ), [33] [34] сообщил, что существует не менее 12 вариантов произношения. [35] В начале 1900-х годов Los Angeles Times выступала за произношение Loce AHNG-hayl-ais ( / l oʊ s ˈ ɑː ŋ h eɪ l eɪ s / ), приближаясь к испанскому [los ˈaŋxeles] , печатая переписывание под заголовком в течение нескольких лет. [36] Это не нашло поддержки. [37]

С 1930-х годов наиболее распространенным было произношение / l ɔː s ˈ æ n dʒ əl ə s / . [38] В 1934 году Совет по географическим названиям США постановил, что это произношение должно использоваться федеральным правительством. [36] Это также было одобрено в 1952 году «жюри», назначенным мэром Флетчером Боуроном для разработки официального произношения. [32] [36]

Распространенные произношения в Соединенном Королевстве включают / l ɒ s ˈ æ n dʒ ɪ l iː z , - l ɪ z , - l ɪ s / loss AN -jil-eez, -iz, -iss . [39] Фонетик Джек Виндзор Льюис описал наиболее распространенное из них, / l ɒ s ˈ æ n dʒ ɪ l iː z / , какпроизношение,основанное на аналогии с греческими словами, оканчивающимися на-es, «отражающее время, когда классика была известна, если испанский язык не был известен».[40]

Поселение коренных калифорнийцев в современном бассейне Лос-Анджелеса и долине Сан-Фернандо находилось под контролем тонгва (теперь также известных как Габриэленьо со времен испанской колонизации). Историческим центром власти тонгва в регионе было поселение Яанга ( тонгва : Iyáangẚ ), что означает «место ядовитого дуба », которое однажды станет местом, где испанцы основали Пуэбло- де-Лос-Анхелес . Iyáangẚ также переводится как «долина дыма». [41] [42] [43] [44] [19]

Морской исследователь Хуан Родригес Кабрильо заявил права на территорию южной Калифорнии для Испанской империи в 1542 году, во время официальной военной исследовательской экспедиции, когда он двигался на север вдоль побережья Тихого океана из более ранних колонизационных баз Новой Испании в Центральной и Южной Америке. [45] Гаспар де Портола и францисканский миссионер Хуан Креспи достигли нынешнего местоположения Лос-Анджелеса 2 августа 1769 года. [46]

_(cropped).jpg/440px-Mission_San_Fernando_Rey_de_España_(Oriana_Day)_(cropped).jpg)

В 1771 году францисканский монах Хуниперо Серра руководил строительством миссии Сан-Габриэль Арканхель , первой миссии в этом районе. [47] 4 сентября 1781 года группа из 44 поселенцев, известных как « Лос-Побладорес », основала пуэбло (город), который они назвали Эль-Пуэбло-де-Нуэстра-Сеньора-ла-Рейна-де-лос-Анхелес , «Город Богоматери — Королевы Ангелов». [29] В современном городе находится крупнейшая римско-католическая архиепархия в Соединенных Штатах. Две трети мексиканских или ( Новой Испании ) поселенцев были метисами или мулатами , смесью африканского, коренного и европейского происхождения. [48] Поселение оставалось небольшим ранчо-городком в течение десятилетий, но к 1820 году население увеличилось примерно до 650 жителей. [49] Сегодня память о пуэбло увековечена в историческом районе Лос-Анджелеса — Пуэбло Плаза и Ольвера-стрит , старейшей части Лос-Анджелеса. [50]

_(detail).jpg/440px-Portrait_of_Pio_Pico_(Californian_State_Library)_(detail).jpg)

Новая Испания обрела независимость от Испанской империи в 1821 году, и пуэбло теперь существовало в составе новой Мексиканской Республики . Во время правления Мексики губернатор Пио Пико сделал Лос-Анджелес региональной столицей Верхней Калифорнии . [51] К этому времени новая республика ввела больше актов секуляризации в регионе Лос-Анджелеса. [52] В 1846 году, во время более масштабной мексикано-американской войны , морские пехотинцы из Соединенных Штатов заняли пуэбло. Это привело к осаде Лос-Анджелеса , где 150 мексиканских ополченцев сражались с оккупантами, которые в конечном итоге сдались. [53]

Мексиканское правление закончилось после американского завоевания Калифорнии , части более крупной мексикано-американской войны . Американцы взяли под контроль калифорнийцев после серии сражений, кульминацией которых стало подписание Договора Кауэнги 13 января 1847 года. [54] Мексиканская уступка была официально оформлена в Договоре Гваделупе-Идальго в 1848 году, по которому Лос-Анджелес и остальная часть Верхней Калифорнии уступили Соединенным Штатам.

Железные дороги появились с завершением трансконтинентальной линии Southern Pacific из Нового Орлеана в Лос-Анджелес в 1876 году и железной дороги Санта-Фе в 1885 году. [55] Нефть была обнаружена в городе и его окрестностях в 1892 году, и к 1923 году эти открытия помогли Калифорнии стать крупнейшим производителем нефти в стране, на долю которого приходилось около четверти мировой добычи нефти. [56]

К 1900 году население выросло до более чем 102 000 человек, [57] что оказало давление на водоснабжение города . [58] Завершение строительства акведука Лос-Анджелеса в 1913 году под руководством Уильяма Малхолланда обеспечило дальнейший рост города. [59] Из-за положений в уставе города, которые запрещали городу Лос-Анджелес продавать или поставлять воду из акведука в любую область за его пределами, многие соседние города и общины были вынуждены присоединиться к Лос-Анджелесу. [60] [61] [62]

.jpg/440px-Paramount_Pictures_studio_gate,_c._1940_(cropped).jpg)

Лос-Анджелес создал первый муниципальный указ о зонировании в Соединенных Штатах. 14 сентября 1908 года городской совет Лос-Анджелеса обнародовал жилые и промышленные зоны землепользования. Новый указ установил три жилые зоны одного типа, где промышленное использование было запрещено. Запреты включали амбары, склады пиломатериалов и любое промышленное использование земли с использованием машинного оборудования. Эти законы применялись к промышленным объектам постфактум. Эти запреты были добавлены к существующим видам деятельности, которые уже регулировались как помехи. К ним относились складирование взрывчатых веществ, газовые работы, бурение нефтяных скважин, скотобойни и кожевенные заводы . Городской совет Лос-Анджелеса также определил семь промышленных зон в городе. Однако между 1908 и 1915 годами городской совет Лос-Анджелеса создал различные исключения из широких запретов, которые применялись к этим трем жилым зонам, и, как следствие, в них появились некоторые промышленные виды использования. Между Указом о жилых районах 1908 года и более поздними законами о зонировании в Соединенных Штатах есть два различия. Во-первых, законы 1908 года не устанавливали всеобъемлющую карту зонирования, как это сделало Постановление о зонировании Нью-Йорка 1916 года . Во-вторых, жилые зоны не различали типы жилья; они рассматривали квартиры, гостиницы и отдельно стоящие односемейные дома в равной степени. [63]

В 1910 году Голливуд объединился с Лос-Анджелесом, и в то время в городе уже работало 10 кинокомпаний. К 1921 году более 80 процентов мировой киноиндустрии было сосредоточено в Лос-Анджелесе. [64] Деньги, полученные от этой индустрии, позволили городу избежать большей части экономических потерь, понесенных остальной частью страны во время Великой депрессии . [65] К 1930 году население превысило один миллион человек. [66] В 1932 году город принимал летние Олимпийские игры .

Во время Второй мировой войны Лос-Анджелес был крупным центром военного производства, такого как судостроение и авиастроение. Calship построила сотни кораблей Liberty и Victory на острове Терминал, а район Лос-Анджелеса был штаб-квартирой шести крупнейших производителей самолетов страны ( Douglas Aircraft Company , Hughes Aircraft , Lockheed , North American Aviation , Northrop Corporation и Vultee ). Во время войны за один год было произведено больше самолетов, чем за все довоенные годы с тех пор, как братья Райт подняли первый самолет в 1903 году, вместе взятые. Производство в Лос-Анджелесе взлетело до небес, и, как сказал Уильям С. Кнудсен из Национальной консультативной комиссии по обороне, «Мы победили, потому что задушили врага лавиной производства, подобной которой он никогда не видел и не мог себе представить». [67]

После окончания Второй мировой войны Лос-Анджелес рос быстрее, чем когда-либо, распространившись на долину Сан-Фернандо . [68] Расширение государственной системы межштатных автомагистралей в 1950-х и 1960-х годах способствовало росту пригородов и ознаменовало упадок частной электрифицированной железнодорожной системы города , когда-то крупнейшей в мире.

В результате Второй мировой войны, роста пригородов и плотности населения в этом районе было построено и работало множество парков развлечений. [69] Примером может служить Беверли-парк , который располагался на углу бульвара Беверли и Ла-Сьенега, прежде чем был закрыт и заменен Беверли-центром . [70]

Во второй половине 20-го века Лос-Анджелес существенно сократил количество жилья, которое можно было построить, резко сузив зону города. В 1960 году город имел общую зонированную вместимость приблизительно для 10 миллионов человек. К 1990 году эта вместимость упала до 4,5 миллионов в результате политических решений запретить жилье посредством зонирования. [71]

Расовая напряженность привела к беспорядкам в Уоттсе в 1965 году, в результате которых погибло 34 человека и более 1000 получили ранения. [72]

В 1969 году Калифорния стала местом рождения Интернета, поскольку первая передача данных по сети ARPANET была отправлена из Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе (UCLA) в Стэнфордский исследовательский институт в Менло-Парке . [73]

В 1973 году Том Брэдли был избран первым афроамериканским мэром города и проработал на этом посту пять сроков, пока не ушел на пенсию в 1993 году. Другие события в городе в 1970-х годах включали противостояние Симбионистской армии освобождения в Южном Централе в 1974 году и дела об убийствах «Хиллсайдских душителей» в 1977–1978 годах. [74]

В начале 1984 года город превзошел Чикаго по численности населения, став вторым по величине городом в США.

В 1984 году город во второй раз принимал Летние Олимпийские игры . Несмотря на бойкот со стороны 14 коммунистических стран , Олимпиада 1984 года стала более финансово успешной, чем любая предыдущая, [75] и второй Олимпиадой, которая принесла прибыль; другой, согласно анализу современных газетных сообщений, была Летняя Олимпиада 1932 года , также проходившая в Лос-Анджелесе. [76]

.jpg/440px-48_California_Willshire_Grand_(cropped).jpg)

Расовая напряженность вспыхнула 29 апреля 1992 года, когда присяжные Сими-Вэлли оправдали четверых сотрудников полицейского департамента Лос-Анджелеса (LAPD), запечатленных на видео во время избиения Родни Кинга , что привело к масштабным беспорядкам . [77] [78]

В 1994 году землетрясение магнитудой 6,7 в Нортридже потрясло город, нанеся ущерб на сумму 12,5 млрд долларов и унеся жизни 72 человек. [79] Столетие закончилось скандалом Rampart , одним из самых масштабных задокументированных случаев неправомерных действий полиции в истории Америки. [80]

В 2002 году мэр Джеймс Хан возглавил кампанию против отделения, в результате которой избиратели отклонили попытки долины Сан-Фернандо и Голливуда отделиться от города. [81]

В 2022 году Карен Басс стала первой женщиной- мэром города , сделав Лос-Анджелес крупнейшим городом США, мэром которого когда-либо была женщина. [82]

Лос-Анджелес примет летние Олимпийские игры и Паралимпийские игры 2028 года , что сделает Лос-Анджелес третьим городом, принимавшим Олимпиаду трижды. [83] [84]

Город Лос-Анджелес занимает общую площадь в 502,7 квадратных миль (1302 км 2 ), включая 468,7 квадратных миль (1214 км 2 ) суши и 34,0 квадратных миль (88 км 2 ) воды. [85] Город простирается на 44 мили (71 км) с севера на юг и на 29 миль (47 км) с востока на запад. Периметр города составляет 342 мили (550 км).

Лос-Анджелес и плоский, и холмистый. Самая высокая точка города — гора Люкенс высотой 5074 фута (1547 м) [86] [87] , расположенная у подножия гор Сан-Габриэль на севере долины Кресента . Восточный конец гор Санта-Моника тянется от центра города до Тихого океана и отделяет бассейн Лос-Анджелеса от долины Сан-Фернандо. Другие холмистые части Лос-Анджелеса включают район горы Вашингтон к северу от центра города, восточные части, такие как Бойл-Хайтс , район Креншоу вокруг холмов Болдуин и район Сан-Педро .

Город окружают гораздо более высокие горы. Сразу на севере лежат горы Сан-Габриэль , которые являются популярной зоной отдыха для жителей Лос-Анджелеса. Его самая высокая точка — гора Сан-Антонио , местное название — гора Болди, которая достигает 10 064 футов (3 068 м). Дальше самая высокая точка в южной Калифорнии — гора Сан-Горгонио , в 81 миле (130 км) к востоку от центра Лос-Анджелеса, [88] высотой 11 503 фута (3 506 м).

Река Лос-Анджелес , которая в значительной степени сезонная, является основным дренажным каналом . Она была выпрямлена и облицована 51 милей (82 км) бетона инженерным корпусом армии, чтобы служить каналом для контроля наводнений. [89] Река берет начало в районе Канога-Парк города, течет на восток от долины Сан-Фернандо вдоль северного края гор Санта-Моника и поворачивает на юг через центр города, впадая в свое устье в порту Лонг-Бич в Тихом океане. Меньший ручей Баллона-Крик впадает в залив Санта-Моника в Плайя-дель-Рей .

Лос-Анджелес богат местными видами растений отчасти из-за разнообразия мест обитания, включая пляжи, водно-болотные угодья и горы. Наиболее распространенными растительными сообществами являются прибрежные кустарники шалфея , кустарники чапараля и прибрежные леса . [90] Местные растения включают: калифорнийский мак , мак матилия , тойон , красноцвет , шамизу , прибрежный живой дуб , платан , иву и гигантскую дикую рожь . Многие из этих местных видов, такие как подсолнечник Лос-Анджелеса , стали настолько редкими, что считаются находящимися под угрозой исчезновения. Мексиканские веерные пальмы , пальмы Канарских островов , королевские пальмы , финиковые пальмы и калифорнийские веерные пальмы распространены в районе Лос-Анджелеса, хотя только последний является родным для Калифорнии, хотя все еще не родным для города Лос-Анджелес.

В Лос-Анджелесе есть ряд официальных растений:

В городе проживает городская популяция рысей ( Lynx rufus ) . [94] Чесотка является распространенной проблемой в этой популяции. [94] Хотя Серейс и др. 2014 обнаружили селекцию иммунной генетики в нескольких локусах, они не продемонстрировали, что это создает реальную разницу , которая помогает рысям пережить будущие вспышки чесотки . [94]

Лос-Анджелес подвержен землетрясениям из-за своего расположения на Тихоокеанском огненном кольце . Геологическая нестабильность привела к образованию многочисленных разломов , которые ежегодно вызывают около 10 000 землетрясений в Южной Калифорнии, хотя большинство из них слишком малы, чтобы ощущаться. [95] Сдвиговая система разломов Сан - Андреас , которая находится на границе между Тихоокеанской и Североамериканской плитами , проходит через столичный район Лос-Анджелеса. Участок разлома, проходящий через Южную Калифорнию, испытывает сильное землетрясение примерно каждые 110–140 лет, и сейсмологи предупреждают о следующем «большом», поскольку последним сильным землетрясением было землетрясение в Форт-Техоне в 1857 году . [96] Бассейн Лос-Анджелеса и столичный район также подвержены риску слепых надвиговых землетрясений . [97] Крупные землетрясения, произошедшие в районе Лос-Анджелеса, включают в себя события в Лонг-Бич 1933 года , Сан-Фернандо 1971 года , Уиттиер-Нэрроус 1987 года и Нортридж 1994 года . Все, за исключением нескольких, имеют низкую интенсивность и не ощущаются. Геологическая служба США (USGS) опубликовала прогноз землетрясений в Калифорнии UCERF , который моделирует возникновение землетрясений в Калифорнии. Части города также уязвимы для цунами ; портовые районы были повреждены волнами от землетрясения на Алеутских островах в 1946 году, землетрясения в Вальдивии в 1960 году, землетрясения на Аляске в 1964 году, землетрясения в Чили в 2010 году и землетрясения в Японии в 2011 году. [98]

Город разделен на множество различных районов и кварталов, [99] [100] некоторые из которых были отдельными городами, которые в конечном итоге объединились с Лос-Анджелесом. [101] Эти кварталы развивались по частям и достаточно четко обозначены, чтобы в городе были вывески, которые отмечают почти все из них. [102]

Городские уличные схемы обычно следуют сетчатому плану с одинаковой длиной кварталов и случайными дорогами, пересекающими кварталы. Однако это осложняется неровной местностью, что потребовало наличия различных сеток для каждой из долин, которые охватывает Лос-Анджелес. Главные улицы спроектированы для перемещения больших объемов трафика через многие части города, многие из которых чрезвычайно длинные; бульвар Сепульведа имеет длину 43 мили (69 км), в то время как бульвар Футхилл имеет длину более 60 миль (97 км), достигая на востоке Сан-Бернардино. Водители в Лос-Анджелесе страдают от одного из худших периодов часа пик в мире, согласно ежегодному индексу трафика производителя навигационных систем TomTom . Водители Лос-Анджелеса проводят в пробках дополнительно 92 часа каждый год. В час пик, согласно индексу, заторы составляют 80%. [103]

Лос-Анджелес часто характеризуется наличием малоэтажных зданий, в отличие от Нью-Йорка. За исключением нескольких центров, таких как Downtown , Warner Center , Century City , Koreatown , Miracle Mile , Hollywood и Westwood , небоскребы и высотные здания не распространены в Лос-Анджелесе. Несколько небоскребов, построенных за пределами этих районов, часто выделяются на фоне остального окружающего ландшафта. Большая часть строительства ведется отдельными блоками, а не стеной к стене . Однако в самом центре Лос-Анджелеса есть много зданий выше 30 этажей, четырнадцать из которых выше 50 этажей, и два выше 70 этажей, самое высокое из которых — Wilshire Grand Center .

В Лос-Анджелесе двухсезонный полузасушливый климат ( Кеппен : BSh ) с сухим летом и очень мягкой зимой, но он получает больше годовых осадков, чем большинство полузасушливых климатов, едва не достигая границы средиземноморского климата ( Кеппен : Csb на побережье, Csa в противном случае). [105] Дневные температуры, как правило, умеренные круглый год. Зимой они составляют в среднем около 68 °F (20 °C). [106] Осенние месяцы, как правило, жаркие, с основными волнами тепла, обычным явлением в сентябре и октябре, в то время как весенние месяцы, как правило, прохладнее и с большим количеством осадков. В Лос-Анджелесе много солнечного света в течение всего года, в среднем всего 35 дней с измеримыми осадками в год. [107]

Температура в прибрежном бассейне превышает 90 °F (32 °C) в течение дюжины или около того дней в году, от одного дня в месяц в апреле, мае, июне и ноябре до трех дней в месяц в июле, августе, октябре и до пяти дней в сентябре. [107] Температура в долинах Сан-Фернандо и Сан-Габриэль значительно теплее. Температура подвержена значительным суточным колебаниям; во внутренних районах разница между средним дневным минимумом и средним дневным максимумом составляет более 30 °F (17 °C). [108] Средняя годовая температура моря составляет 63 °F (17 °C), от 58 °F (14 °C) в январе до 68 °F (20 °C) в августе. [109] Количество солнечных часов в год составляет более 3000, в среднем от 7 часов солнечного сияния в день в декабре до 12 часов в июле. [110]

Из-за горного рельефа окружающего региона, район Лос-Анджелеса содержит большое количество различных микроклиматов , вызывающих экстремальные колебания температуры в непосредственной близости друг от друга. Например, средняя максимальная температура июля на пирсе Санта-Моники составляет 70 °F (21 °C), тогда как в Канога-парке, в 15 милях (24 км) отсюда, она составляет 95 °F (35 °C). [111] Город, как и большая часть южного побережья Калифорнии, подвержен погодному явлению конца весны/начала лета, называемому « июньским мраком ». Это подразумевает пасмурное или туманное небо утром, которое к полудню уступает место солнцу. [112]

Совсем недавно засухи по всему штату в Калифорнии еще больше подорвали водную безопасность города . [113] В центре Лос-Анджелеса в среднем выпадает 14,67 дюйма (373 мм) осадков в год, в основном в период с ноября по март, [114] [108] как правило, в виде умеренных ливней, но иногда и сильных осадков во время зимних штормов. Количество осадков обычно выше на холмах и прибрежных склонах гор из-за орографического подъема. Летние дни обычно без осадков. Редко вторжение влажного воздуха с юга или востока может принести кратковременные грозы в конце лета, особенно в горы. На побережье выпадает немного меньше осадков, в то время как внутренние и горные районы получают значительно больше. Годы со средним количеством осадков редки. Обычная картина — изменчивость из года в год с короткой чередой сухих лет с 5–10 дюймами (130–250 мм) осадков, за которыми следуют один или два влажных года с более чем 20 дюймами (510 мм). [108] Влажные годы обычно связаны с теплыми водными условиями Эль-Ниньо в Тихом океане, сухие годы — с более прохладными эпизодами Ла-Нинья . Серия дождливых дней может вызвать наводнения в низменностях и оползни в горах, особенно после того, как лесные пожары оголили склоны.

Как отрицательные температуры, так и снегопады чрезвычайно редки в городском бассейне и вдоль побережья, причем последнее появление показаний 32 °F (0 °C) на станции в центре города было 29 января 1979 года; [108] отрицательные температуры случаются почти каждый год в долинах, в то время как горы в пределах города обычно получают снегопады каждую зиму. Наибольший снегопад, зарегистрированный в центре Лос-Анджелеса, составил 2,0 дюйма (5 см) 15 января 1932 года. [108] [115] Хотя самый последний снегопад произошел в феврале 2019 года, первый снегопад с 1962 года, [116] [117] причем снег выпадал в районах, прилегающих к Лос-Анджелесу, совсем недавно, в январе 2021 года. [118] Кратковременные, локализованные случаи града могут происходить в редких случаях, но они более распространены, чем снегопад. На официальной станции в центре города самая высокая зарегистрированная температура составила 113 °F (45 °C) 27 сентября 2010 года [108] [119] , а самая низкая — 28 °F (−2 °C) [108] 4 января 1949 года. [108] В городе Лос-Анджелес самая высокая температура, когда-либо официально зарегистрированная, составила 121 °F (49 °C) 6 сентября 2020 года на метеостанции в колледже Пирса в районе Вудленд-Хиллз в долине Сан-Фернандо . [120] Осенью и зимой ветры Санта-Ана иногда приносят в Лос-Анджелес гораздо более теплые и сухие условия и повышают риск возникновения лесных пожаров.

Из-за географии, сильной зависимости от автомобилей и портового комплекса Лос-Анджелес/Лонг-Бич, Лос-Анджелес страдает от загрязнения воздуха в виде смога. Бассейн Лос-Анджелеса и долина Сан-Фернандо подвержены атмосферной инверсии , которая удерживает выхлопы от дорожных транспортных средств, самолетов, локомотивов, судоходства, производства и других источников. [128]

.jpg/440px-Los_Angeles_Pollution_(cropped).jpg)

Сезон смога длится примерно с мая по октябрь. [129] В то время как другие крупные города полагаются на дождь для очистки смога, Лос-Анджелес получает только 15 дюймов (380 мм) осадков каждый год: загрязнение накапливается в течение многих последовательных дней. Проблемы качества воздуха в Лос-Анджелесе и других крупных городах привели к принятию раннего национального законодательства об охране окружающей среды, включая Закон о чистом воздухе . Когда закон был принят, Калифорния не смогла создать План внедрения штата , который позволил бы ей соответствовать новым стандартам качества воздуха, в основном из-за уровня загрязнения в Лос-Анджелесе, создаваемого старыми транспортными средствами. [130] Совсем недавно штат Калифорния возглавил страну в работе по ограничению загрязнения, введя обязательные транспортные средства с низким уровнем выбросов . Ожидается, что смог продолжит снижаться в ближайшие годы из-за агрессивных шагов по его сокращению, которые включают электрические и гибридные автомобили, улучшения в общественном транспорте и другие меры.

Количество предупреждений о смоге 1-й стадии в Лос-Анджелесе снизилось с более чем 100 в год в 1970-х годах до почти нуля в новом тысячелетии. [131] Несмотря на улучшение, ежегодные отчеты Американской ассоциации легких за 2006 и 2007 годы оценили город как самый загрязненный в стране с краткосрочным загрязнением частицами и круглогодичным загрязнением частицами. [132] В 2008 году город был признан вторым по загрязнению и снова имел самый высокий круглогодичный уровень загрязнения частицами. [133] Город достиг своей цели по обеспечению 20 процентов электроэнергии города из возобновляемых источников в 2010 году. [134] Исследование Американской ассоциации легких за 2013 год оценивает столичный регион как имеющий самый сильный смог в стране и четвертый по объему как краткосрочного, так и круглогодичного загрязнения. [135]

Лос-Анджелес также является домом для крупнейшего в стране городского нефтяного месторождения . В радиусе 1500 футов (460 м) от домов, церквей, школ и больниц города находится более 700 действующих нефтяных скважин, и Агентство по охране окружающей среды выразило серьезную обеспокоенность по поводу этой ситуации. [136]

Перепись населения США 2010 года [139] сообщила, что население Лос-Анджелеса составляло 3 792 621 человек. [140] Плотность населения составляла 8 092,3 человека на квадратную милю (3 124,5 человека/км 2 ). Возрастное распределение было следующим: 874 525 человек (23,1%) в возрасте до 18 лет, 434 478 человек (11,5%) от 18 до 24 лет, 1 209 367 человек (31,9%) от 25 до 44 лет, 877 555 человек (23,1%) от 45 до 64 лет и 396 696 человек (10,5%) в возрасте 65 лет и старше. [140] Средний возраст составил 34,1 года. На каждые 100 женщин приходилось 99,2 мужчин. На каждые 100 женщин в возрасте 18 лет и старше приходилось 97,6 мужчин. [140]

Было 1 413 995 единиц жилья — по сравнению с 1 298 350 в 2005–2009 годах [140] — при средней плотности 2 812,8 домохозяйств на квадратную милю (1 086,0 домохозяйств/км 2 ), из которых 503 863 (38,2%) занимали владельцы, а 814 305 (61,8%) занимали арендаторы. Уровень вакантных площадей для владельцев жилья составлял 2,1%; уровень вакантных площадей для сдачи в аренду составлял 6,1%. 1 535 444 человека (40,5% населения) жили в жилых помещениях, занимаемых владельцами, а 2 172 576 человек (57,3%) жили в арендных жилых помещениях. [140]

По данным переписи населения США 2010 года, в Лос-Анджелесе средний доход домохозяйства составлял 49 497 долларов США, при этом 22,0% населения жили за федеральной чертой бедности. [140]

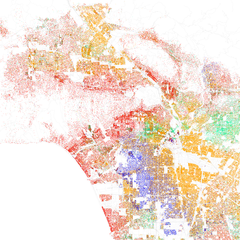

Согласно переписи 2010 года , расовый состав Лос-Анджелеса включал: 1 888 158 белых (49,8%), 365 118 афроамериканцев (9,6%), 28 215 коренных американцев (0,7%), 426 959 азиатов (11,3%), 5 577 жителей островов Тихого океана (0,1%), 902 959 представителей других рас (23,8%) и 175 635 (4,6%) представителей двух или более рас . [140] Было 1 838 822 испаноязычных или латиноамериканских жителей любой расы (48,5%). Лос-Анджелес является домом для людей из более чем 140 стран, говорящих на 224 различных идентифицированных языках. [143] Этнические анклавы , такие как Чайнатаун , Исторический Филиппинский квартал , Кореатаун , Маленькая Армения , Маленькая Эфиопия , Техрангелес , Маленький Токио , Маленький Бангладеш и Тайский квартал, являются примерами многоязычного характера Лос-Анджелеса.

В 2010 году доля неиспаноязычных белых составляла 28,7% населения [140] по сравнению с 86,3% в 1940 году [141]. Большая часть неиспаноязычного белого населения проживает в районах вдоль побережья Тихого океана, а также в районах вблизи гор Санта-Моника и на них, от Пасифик -Палисейдс до Лос-Фелиса .

Мексиканское происхождение составляет самую большую этническую группу латиноамериканцев, 31,9% населения города, за ней следуют выходцы из Сальвадора (6,0%) и Гватемалы (3,6%). Испаноязычное население имеет давно сложившуюся мексикано-американскую и центральноамериканскую общину и распространено по всему городу Лос-Анджелес и его столичной области. Оно наиболее сильно сконцентрировано в регионах вокруг центра города, таких как Восточный Лос-Анджелес , Северо-Восточный Лос-Анджелес и Уэстлейк . Кроме того, подавляющее большинство жителей в районах на востоке Южного Лос-Анджелеса в направлении Дауни имеют испаноязычное происхождение. [144]

Крупнейшими азиатскими этническими группами являются филиппинцы (3,2%) и корейцы (2,9%), которые имеют свои собственные устоявшиеся этнические анклавы — Koreatown в Wilshire Center и Historic Filipinotown . [145] Китайцы , которые составляют 1,8% населения Лос-Анджелеса, проживают в основном за пределами городской черты Лос-Анджелеса, в долине Сан-Габриэль на востоке округа Лос-Анджелес, но имеют значительное присутствие в городе, особенно в Chinatown . [146] Chinatown и Thaitown также являются домом для многих тайцев и камбоджийцев , которые составляют 0,3% и 0,1% населения Лос-Анджелеса соответственно. Японцы составляют 0,9% населения города и имеют устоявшийся Little Tokyo в центре города, а еще одна значительная община японо-американцев находится в районе Sawtelle в Западном Лос-Анджелесе. Вьетнамцы составляют 0,5% населения Лос-Анджелеса. Индийцы составляют 0,9% населения города. Лос-Анджелес также является домом для армян , ассирийцев и иранцев , многие из которых живут в анклавах, таких как Маленькая Армения и Тегеранджелес . [147] [148]

Афроамериканцы были преобладающей этнической группой в Южном Лос-Анджелесе , который стал крупнейшей афроамериканской общиной на западе Соединенных Штатов с 1960-х годов. Районы Южного Лос-Анджелеса с самой высокой концентрацией афроамериканцев включают Креншоу , Болдуин-Хиллз , Леймерт-Парк , Гайд-Парк , Грамерси-Парк , Манчестер-сквер и Уоттс . [149] Также в районе Фэрфакса есть значительная эритрейская и эфиопская общины. [150]

В Лос-Анджелесе проживает второе по величине население Мексики, Армении, Сальвадора, Филиппин и Гватемалы по городам мира, третье по величине население Канады в мире, а также самое большое количество японцев, иранцев/персов, камбоджийцев и цыган в стране. [151] Итальянская община сосредоточена в Сан-Педро. [152]

Большинство иностранцев, проживающих в Лос-Анджелесе, родились в Мексике , Сальвадоре , Гватемале , на Филиппинах и в Южной Корее . [153]

Согласно исследованию, проведенному в 2014 году исследовательским центром Pew , христианство является наиболее распространенной религией в Лос-Анджелесе (65%). [154] [155] Римско -католическая архиепархия Лос-Анджелеса является крупнейшей архиепархией в стране. [156] Кардинал Роджер Махони , будучи архиепископом, руководил строительством собора Богоматери Ангелов , который открылся в сентябре 2002 года в центре Лос-Анджелеса. [157]

В 2011 году некогда распространенный, но в конечном итоге утративший силу обычай проведения процессии и мессы в честь Нуэстра Сеньора де лос Анхелес в ознаменование основания города Лос-Анджелес в 1781 году был возрожден Фондом Королевы Ангелов и его основателем Марком Альбертом при поддержке Архиепископии Лос-Анджелеса, а также нескольких гражданских лидеров. [158] Недавно возрожденный обычай является продолжением первоначальных процессий и месс, которые начались в первую годовщину основания Лос-Анджелеса в 1782 году и продолжались в течение почти столетия после этого.

_(cropped).jpg/440px-St._Vincent_de_Paul_Catholic_Church_(Los_Angeles)_(cropped).jpg)

С 621 000 евреев в столичном регионе, регион имеет второе по величине еврейское население в Соединенных Штатах, после Нью-Йорка . [159] Многие из евреев Лос-Анджелеса сейчас живут в Вестсайде и в долине Сан-Фернандо , хотя в Бойл-Хайтс когда-то было большое еврейское население до Второй мировой войны из-за ограничительных жилищных соглашений. Основные ортодоксальные еврейские кварталы включают Хэнкок-Парк , Пико-Робертсон и Вэлли-Виллидж , в то время как еврейские израильтяне хорошо представлены в районах Энсино и Тарзана , а персидские евреи в Беверли-Хиллз . Многие разновидности иудаизма представлены в районе Большого Лос-Анджелеса, включая реформистский , консервативный , ортодоксальный и реконструкционистский . Синагога Брид-стрит в Восточном Лос-Анджелесе , построенная в 1923 году, была крупнейшей синагогой к западу от Чикаго в первые десятилетия своего существования; она больше не используется ежедневно как синагога и преобразуется в музей и общественный центр. [160] [161] В городе также есть Центр Каббалы. [ 162 ]

Международная церковь Foursquare Gospel была основана в Лос-Анджелесе Эйми Семпл Макферсон в 1923 году и по сей день имеет там штаб-квартиру. В течение многих лет церковь собиралась в Angelus Temple , который на момент своего строительства был одной из крупнейших церквей в стране. [163]

.jpg/440px-Wilshire_Boulevard_Temple_2017_(cropped).jpg)

Лос-Анджелес имеет богатую и влиятельную протестантскую традицию. Первая протестантская служба в Лос-Анджелесе была методистским собранием, проведенным в частном доме в 1850 году, а старейшая протестантская церковь, которая все еще действует, Первая конгрегационалистская церковь , была основана в 1867 году. [164] В начале 1900-х годов Библейский институт Лос-Анджелеса опубликовал учредительные документы движения христианских фундаменталистов , а Возрождение на Азуза-стрит положило начало пятидесятничеству . [164] Церковь Metropolitan Community также берет свое начало в районе Лос-Анджелеса. [165] Важные церкви в городе включают Первую пресвитерианскую церковь Голливуда , Пресвитерианскую церковь Бель-Эйр , Первую африканскую методистскую епископальную церковь Лос-Анджелеса , Церковь Бога во Христе Западного Анжелеса , Вторую баптистскую церковь , Христианский центр Креншоу , Мемориальную христианскую церковь Маккарти и Первую конгрегационалистскую церковь.

Храм в Лос-Анджелесе, Калифорния , второй по величине храм, управляемый Церковью Иисуса Христа Святых последних дней , находится на бульваре Санта-Моника в районе Вествуд в Лос-Анджелесе. Освященный в 1956 году, он был первым храмом Церкви Иисуса Христа Святых последних дней, построенным в Калифорнии , и он был крупнейшим в мире после завершения строительства. [166]

В районе Голливуда в Лос-Анджелесе также есть несколько крупных штаб-квартир, церквей и Центр знаменитостей Саентологии . [167] [168]

Из-за большого многонационального населения Лос-Анджелеса практикуется широкий спектр верований, включая буддизм , индуизм , ислам , зороастризм , сикхизм , бахаи , различные восточные православные церкви , суфизм , синтоизм , даосизм , конфуцианство , китайскую народную религию и бесчисленное множество других. Например, иммигранты из Азии сформировали ряд значительных буддийских общин, сделав город домом для самого большого количества буддистов в мире. Первая буддийская кумирня была основана в городе в 1875 году. [164] Атеизм и другие светские верования также распространены, поскольку город является крупнейшим в западном поясе нецерковных общин США .

.jpg/440px-Homeless_people,_Los_Angeles,_California_(cropped).jpg)

По состоянию на январь 2020 года в городе Лос-Анджелес насчитывалось 41 290 бездомных , что составляет примерно 62% от общего числа бездомных в округе Лос-Анджелес. [169] Это на 14,2% больше, чем в предыдущем году (при росте общего числа бездомных в округе Лос-Анджелес на 12,7%). [170] [171] Эпицентром бездомности в Лос-Анджелесе является район Скид-Роу , в котором проживает 8000 бездомных, что является одной из крупнейших стабильных групп бездомных в Соединенных Штатах. [172] [173] Рост числа бездомных в Лос-Анджелесе объясняется недоступностью жилья [174] и злоупотреблением психоактивными веществами. [175] Почти 60 процентов из 82 955 человек, которые стали бездомными в 2019 году, заявили, что их бездомность связана с экономическими трудностями. [170] В Лос-Анджелесе чернокожие люди примерно в четыре раза чаще сталкиваются с бездомностью. [170] [176]

Экономика Лос-Анджелеса основана на международной торговле, развлечениях (телевидение, кино, видеоигры, запись музыки и производство), аэрокосмической промышленности, технологиях, нефти, моде, одежде и туризме. [177] Другие значимые отрасли включают финансы, телекоммуникации, юриспруденцию, здравоохранение и транспорт . В Индексе глобальных финансовых центров 2017 года Лос-Анджелес занял 19-е место среди самых конкурентоспособных финансовых центров в мире и шестое место среди самых конкурентоспособных в США после Нью-Йорка , Сан-Франциско , Чикаго , Бостона и Вашингтона, округ Колумбия. [178] Хотя после пандемии COVID-19 произошел отток бизнеса из центра Лос-Анджелеса , предпринимаются усилия по переосмыслению городского ядра города как культурного центра с крупнейшей в мире витриной архитектуры, спроектированной Фрэнком Гери . [28]

Из пяти крупных киностудий только Paramount Pictures находится в черте города Лос-Анджелеса; [179] она расположена в так называемой Тридцатимильной зоне штаб-квартир индустрии развлечений в Южной Калифорнии.

Лос-Анджелес является крупнейшим производственным центром в Соединенных Штатах. [180] Смежные порты Лос-Анджелеса и Лонг-Бич вместе составляют самый загруженный порт в Соединенных Штатах по некоторым показателям и пятый по загруженности порт в мире, жизненно важный для торговли в Тихоокеанском регионе . [181]

.jpg/440px-Los_Angeles_Harbor_-_panoramio_-_Zzyzx_(1).jpg)

Валовой городской продукт столичного региона Лос -Анджелеса составляет более 1,0 триллиона долларов (по состоянию на 2018 год ), [27] что делает его третьим по величине экономическим городом в мире после Нью-Йорка и Токио . [27] Лос-Анджелес был классифицирован как « альфа-мировой город » согласно исследованию, проведенному в 2012 году группой из Университета Лафборо . [182][update]

Департамент регулирования каннабиса обеспечивает соблюдение законодательства о каннабисе после легализации продажи и распространения каннабиса в 2016 году. [183] По состоянию на октябрь 2019 года [update]более 300 существующих предприятий, занимающихся каннабисом (как розничные торговцы, так и их поставщики), получили разрешение на работу на рынке, который считается крупнейшим в стране. [184] [185]

По состоянию на 2018 год [update]в Лос-Анджелесе базируются три компании из списка Fortune 500 : AECOM , CBRE Group и Reliance Steel & Aluminum Co. [ 186] Другие компании со штаб-квартирами в Лос-Анджелесе и прилегающих районах включают The Aerospace Corporation , California Pizza Kitchen , [187] Capital Group Companies , Deluxe Entertainment Services Group , Dine Brands Global , DreamWorks Animation , Dollar Shave Club , Fandango Media , Farmers Insurance Group , Forever 21 , Hulu , Panda Express , SpaceX , Ubisoft Film & Television , The Walt Disney Company , Universal Pictures , Warner Bros. , Warner Music Group и Trader Joe's .

.tif/lossy-page1-440px-Skyline_view_of_Los_Angeles,_California_LCCN2013631685_(cropped).tif.jpg)

Лос-Анджелес часто называют творческой столицей мира, потому что каждый шестой его житель работает в творческой индустрии [189] , и в Лос-Анджелесе живет и работает больше художников, писателей, режиссеров, актеров, танцоров и музыкантов, чем в любом другом городе в любое другое время в мировой истории . [190] Город также известен своими плодовитыми фресками . [191]

Архитектура Лос-Анджелеса находится под влиянием испанских, мексиканских и американских корней. Популярные стили в городе включают испанский колониальный стиль возрождения, стиль возрождения миссии , калифорнийский стиль чурригереско, средиземноморский стиль возрождения , стиль ар-деко и стиль модерн середины века , среди прочих.

Важные достопримечательности Лос-Анджелеса включают в себя Знак Голливуда , [192] Концертный зал Уолта Диснея , Здание Capitol Records , [193] Собор Богоматери Ангелов , [194] Полет Ангелов , [195] Китайский театр Граумана , [196] Театр Долби , [197] Обсерватория Гриффита , [198] Центр Гетти , [199] Вилла Гетти , [200] Дом Шталя , [201] Мемориальный Колизей Лос-Анджелеса , LA Live , [202] Музей искусств округа Лос-Анджелес , Исторический район Венецианского канала и набережная, Тематическое здание , Здание Брэдбери , Башня банка США , Центр Уилшир Гранд , Голливудский бульвар , Мэрия Лос-Анджелеса , Голливудская чаша , [203] линкор USS Iowa , Башни Уоттса , [204] Crypto.com Арена , стадион «Доджер» и улица Олвера . [205]

.jpg/440px-Chinese_Theatre_(26776735090).jpg)

Исполнительское искусство играет важную роль в культурной идентичности Лос-Анджелеса. По данным Института инноваций имени Стивенса при Университете Южной Калифорнии, «ежегодно проводится более 1100 театральных постановок и 21 открытие каждую неделю». [190] Музыкальный центр Лос-Анджелеса является «одним из трех крупнейших центров исполнительского искусства в стране», ежегодно его посещают более 1,3 миллиона человек. [206] Концертный зал Уолта Диснея , центральное место Музыкального центра, является домом для престижной филармонии Лос-Анджелеса . [207] Такие известные организации, как Center Theatre Group , Los Angeles Master Chorale и Los Angeles Opera, также являются резидентами Музыкального центра. [208] [209] [210] Таланты развиваются на местном уровне в ведущих учреждениях, таких как Colburn School и USC Thornton School of Music .

Район Голливуд в городе признан центром киноиндустрии , сохраняя это звание с начала 20-го века, а район Лос-Анджелеса также ассоциируется с тем, что является центром телевизионной индустрии . [211] В городе находятся крупные киностудии, а также крупные звукозаписывающие компании. В Лос-Анджелесе ежегодно проходят церемонии вручения премии «Оскар» , премии «Эмми» и премии «Грэмми» , а также множество других наград в индустрии развлечений. В Лос-Анджелесе находится Школа кинематографических искусств Университета Южной Калифорнии , которая является старейшей киношколой в Соединенных Штатах. [212]

В округе Лос-Анджелес насчитывается 841 музей и художественная галерея [213] , что больше музеев на душу населения, чем в любом другом городе США [213]. Некоторые из известных музеев — это Музей искусств округа Лос-Анджелес (крупнейший художественный музей на западе США [214] ), Центр Гетти (часть фонда Дж. Пола Гетти , самого богатого в мире художественного учреждения [215] ), Автомобильный музей Петерсена [216] , Библиотека Хантингтона [217] , Музей естественной истории [218] , Battleship Iowa [219] , The Broad , в котором хранится более 2000 произведений современного искусства [220] и Музей современного искусства [221] . Значительное количество художественных галерей находится на Gallery Row , и десятки тысяч людей посещают ежемесячную художественную прогулку Downtown Art Walk. [222]

.jpg/440px-Los_Angeles_Central_Library,_630_W._5th_St._Downtown_Los_Angeles_2_(cropped).jpg)

Система публичной библиотеки Лос-Анджелеса управляет 72 публичными библиотеками в городе. [223] Анклавы некорпоративных территорий обслуживаются филиалами Публичной библиотеки округа Лос-Анджелес , многие из которых находятся в пределах пешей доступности от жителей. [224]

Кулинарная культура Лос-Анджелеса представляет собой слияние мировой кухни, привнесенное богатой историей иммигрантов и населением города. По состоянию на 2022 год гид Мишлен признал 10 ресторанов, присвоив 2 ресторанам две звезды и восьми ресторанам одну звезду. [225]

Латиноамериканские иммигранты, особенно мексиканские , привезли тако , буррито , кесадильи , тортас , тамале и энчиладас, которые подаются в фургонах с едой и на стойке, в такериях и кафе . Азиатские рестораны, многие из которых принадлежат иммигрантам, есть по всему городу, в том числе в Чайнатауне , [226] Кореатауне , [227] и Маленьком Токио . [228] Лос-Анджелес также предлагает огромный выбор веганских, вегетарианских и растительных блюд.

Los Angeles and its metropolitan area are the home of eleven top-level professional sports teams, several of which play in neighboring communities but use Los Angeles in their name. These teams include the Los Angeles Dodgers[229] and Los Angeles Angels[230] of Major League Baseball (MLB), the Los Angeles Rams[231] and Los Angeles Chargers of the National Football League (NFL), the Los Angeles Lakers[232] and Los Angeles Clippers[233] of the National Basketball Association (NBA), the Los Angeles Kings[234] and Anaheim Ducks[235] of the National Hockey League (NHL), the Los Angeles Galaxy[236] and Los Angeles FC[237] of Major League Soccer (MLS), the Los Angeles Sparks of the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA),[238] the SoCal Lashings of Minor League Cricket (MiLC) and the Los Angeles Knight Riders of Major League Cricket (MLC).[239]

Other notable sports teams include the UCLA Bruins and the USC Trojans in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), both of which are Division I teams in the Pac-12 Conference, but will soon be moving to the Big Ten Conference.[240]

Los Angeles is the second-largest city in the United States but hosted no NFL team between 1995 and 2015. At one time, the Los Angeles area hosted two NFL teams: the Rams and the Raiders. Both left the city in 1995, with the Rams moving to St. Louis, and the Raiders moving back to their original home of Oakland. After 21 seasons in St. Louis, on January 12, 2016, the NFL announced the Rams would be moving back to Los Angeles for the 2016 NFL season with its home games played at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for four seasons.[241][242][243] Prior to 1995, the Rams played their home games in the Coliseum from 1946 to 1979 which made them the first professional sports team to play in Los Angeles, and then moved to Anaheim Stadium from 1980 until 1994. The San Diego Chargers announced on January 12, 2017, that they would also relocate back to Los Angeles (the first since its inaugural season in 1960) and become the Los Angeles Chargers beginning in the 2017 NFL season and played at Dignity Health Sports Park in Carson, California for three seasons.[244] The Rams and the Chargers would soon move to the newly built SoFi Stadium, located in nearby Inglewood during the 2020 season.[245]

Los Angeles boasts a number of sports venues, including Dodger Stadium,[246] the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum,[247] BMO Stadium[248] and the Crypto.com Arena.[249] The Forum, SoFi Stadium, Dignity Health Sports Park, the Rose Bowl, Angel Stadium, Honda Center, and Intuit Dome are also in adjacent cities and cities in Los Angeles's metropolitan area.[250]

Los Angeles has twice hosted the Summer Olympic Games: in 1932 and in 1984, and will host the games for a third time in 2028.[251] Los Angeles will be the third city after London (1908, 1948 and 2012) and Paris (1900, 1924 and 2024) to host the Olympic Games three times. When the tenth Olympic Games were hosted in 1932, the former 10th Street was renamed Olympic Blvd. Los Angeles also hosted the Deaflympics in 1985[252] and Special Olympics World Summer Games in 2015.[253]

_by_Subashwilfred_(20180630233148).jpg/440px-LAFC_vs_Philadelphia_Union_(2018)_by_Subashwilfred_(20180630233148).jpg)

Eight NFL Super Bowls were also held in the city and its surrounding areas - two at the Memorial Coliseum (the first Super Bowl, I and VII), five at the Rose Bowl in suburban Pasadena (XI, XIV, XVII, XXI, and XXVII), and one at the suburban Inglewood (LVI).[254] The Rose Bowl also hosts an annual and highly prestigious NCAA college football game called the Rose Bowl, which happens every New Year's Day.

Los Angeles also hosted eight FIFA World Cup soccer games at the Rose Bowl in 1994, including the final, where Brazil won. The Rose Bowl also hosted four matches in the 1999 FIFA Women's World Cup, including the final, where the United States won against China on penalty kicks. This was the game where Brandi Chastain took her shirt off after she scored the tournament-winning penalty kick, creating an iconic image. Los Angeles will be one of eleven U.S. host cities for the 2026 FIFA World Cup with matches set to be held at SoFi Stadium.[255]

Los Angeles is one of six North American cities to have won championships in all five of its major leagues (MLB, NFL, NHL, NBA and MLS), having completed the feat with the Kings' 2012 Stanley Cup title.[256]

.jpg/440px-City_Hall,_LA,_CA,_jjron_22.03.2012_(cropped).jpg)

Los Angeles is a charter city as opposed to a general law city. The current charter was adopted on June 8, 1999, and has been amended many times.[257] The elected government consists of the Los Angeles City Council and the mayor of Los Angeles, which operate under a mayor–council government, as well as the city attorney (not to be confused with the district attorney, a county office) and controller. The mayor is Karen Bass.[258] There are 15 city council districts.

The city has many departments and appointed officers, including the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD),[259] the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners,[260] the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD),[261] the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles (HACLA),[262] the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT),[263] and the Los Angeles Public Library (LAPL).[264]

The charter of the City of Los Angeles ratified by voters in 1999 created a system of advisory neighborhood councils that would represent the diversity of stakeholders, defined as those who live, work or own property in the neighborhood. The neighborhood councils are relatively autonomous and spontaneous in that they identify their own boundaries, establish their own bylaws, and elect their own officers. There are about 90 neighborhood councils.

Residents of Los Angeles elect supervisors for the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th supervisorial districts.

In the California State Assembly, Los Angeles is split between fourteen districts.[265] In the California State Senate, the city is split between eight districts.[266] In the United States House of Representatives, it is split among nine congressional districts.[267]

In 1992, the city of Los Angeles recorded 1,092 murders.[268] Los Angeles experienced a significant decline in crime in the 1990s and late 2000s and reached a 50-year low in 2009 with 314 homicides.[269][270] This is a rate of 7.85 per 100,000 population—a major decrease from 1980 when a homicide rate of 34.2 per 100,000 was reported.[271][272] This included 15 officer-involved shootings. One shooting led to the death of a SWAT team member, Randal Simmons, the first in LAPD's history.[273] Los Angeles in the year of 2013 totaled 251 murders, a decrease of 16 percent from the previous year. Police speculate the drop resulted from a number of factors, including young people spending more time online.[274] In 2021, murders rose to the highest level since 2008 and there were 348.[275]

In 2015, it was revealed that the LAPD had been under-reporting crime for eight years, making the crime rate in the city appear much lower than it really was.[276][277]

The Dragna crime family and Mickey Cohen dominated organized crime in the city during the Prohibition era[278] and reached its peak during the 1940s and 1950s with the "Battle of Sunset Strip" as part of the American Mafia, but has gradually declined since then with the rise of various black and Hispanic gangs in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[278]

According to the Los Angeles Police Department, the city is home to 45,000 gang members, organized into 450 gangs.[279] Among them are the Crips and Bloods, which are both African American street gangs that originated in the South Los Angeles region. Latino street gangs such as the Sureños, a Mexican American street gang, and Mara Salvatrucha, which has mainly members of Salvadoran descent, as well as other Central American descents, all originated in Los Angeles. This has led to the city being referred to as the "Gang Capital of America".[280]

.JPG/440px-Powell_Library_(cropped).JPG)

.jpg/440px-2_2011-09-29_WarnerBldg_Facade_SP-Pano1_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Loyola_Marymount_SunkenGardens_SacredHeartChapel_(cropped).jpg)

There are three public universities within the city limits: California State University, Los Angeles (CSULA), California State University, Northridge (CSUN) and University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).[281]

Private colleges in the city include:

The community college system consists of nine campuses governed by the trustees of the Los Angeles Community College District:

There are numerous additional colleges and universities outside the city limits in the Greater Los Angeles area, including the Claremont Colleges consortium, which includes the most selective liberal arts colleges in the U.S., and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), one of the top STEM-focused research institutions in the world.

Los Angeles Unified School District serves almost all of the city of Los Angeles, as well as several surrounding communities, with a student population around 800,000.[312] After Proposition 13 was approved in 1978, urban school districts had considerable trouble with funding. LAUSD has become known for its underfunded, overcrowded and poorly maintained campuses, although its 162 Magnet schools help compete with local private schools.

Several small sections of Los Angeles are in the Inglewood Unified School District,[313] and the Las Virgenes Unified School District.[314] The Los Angeles County Office of Education operates the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts.

.jpg/440px-Hollywood_Sign_(Zuschnitt).jpg)

The Los Angeles metro area is the second-largest broadcast designated market area in the U.S. (after New York) with 5,431,140 homes (4.956% of the U.S.), which is served by a wide variety of local AM and FM radio and television stations. Los Angeles and New York City are the only two media markets to have seven VHF allocations assigned to them.[315]

The major daily English-language newspaper in the area is the Los Angeles Times.[316] La Opinión is the city's major daily Spanish-language paper.[317] The Korea Times is the city's major daily Korean-language paper while The World Journal is the city and county's major Chinese newspaper. The Los Angeles Sentinel is the city's major African-American weekly paper, boasting the largest African-American readership in the Western United States.[318] Investor's Business Daily is distributed from its LA corporate offices, which are headquartered in Playa del Rey.[319]

As part of the region's aforementioned creative industry, the Big Five major broadcast television networks, ABC, CBS, FOX, NBC, and The CW, all have production facilities and offices throughout various areas of Los Angeles. All four major broadcast television networks, plus major Spanish-language networks Telemundo and Univision, also own and operate stations that both serve the Los Angeles market and serve as each network's West Coast flagship station: ABC's KABC-TV (Channel 7),[320] CBS's KCBS-TV (Channel 2), Fox's KTTV-TV (Channel 11),[321] NBC's KNBC-TV (Channel 4),[322] The CW's KTLA-TV (Channel 5), MyNetworkTV's KCOP-TV (Channel 13), Telemundo's KVEA-TV (Channel 52), and Univision's KMEX-TV (Channel 34). The region also has four PBS member stations, with KCET, re-joining the network as secondary affiliate in August 2019, after spending the previous eight years as the nation's largest independent public television station. KTBN (Channel 40) is the flagship station of the religious Trinity Broadcasting Network, based out of Santa Ana. A variety of independent television stations, such as KCAL-TV (Channel 9), also operate in the area.

.jpg/440px-Paramountpicturesmelrosegate_(cropped).jpg)

There are also a number of smaller regional newspapers, alternative weeklies and magazines, including the Los Angeles Register, Los Angeles Community News, (which focuses on coverage of the greater Los Angeles area), Los Angeles Daily News (which focuses coverage on the San Fernando Valley), LA Weekly, L.A. Record (which focuses coverage on the music scene in the Greater Los Angeles Area), Los Angeles Magazine, the Los Angeles Business Journal, the Los Angeles Daily Journal (legal industry paper), The Hollywood Reporter, Variety (both entertainment industry papers), and Los Angeles Downtown News.[323] In addition to the major papers, numerous local periodicals serve immigrant communities in their native languages, including Armenian, English, Korean, Persian, Russian, Chinese, Japanese, Hebrew, and Arabic. Many cities adjacent to Los Angeles also have their own daily newspapers whose coverage and availability overlaps with certain Los Angeles neighborhoods. Examples include The Daily Breeze (serving the South Bay), and The Long Beach Press-Telegram.

Los Angeles arts, culture and nightlife news is also covered by a number of local and national online guides, including Time Out Los Angeles, Thrillist, Kristin's List, DailyCandy, Diversity News Magazine, LAist, and Flavorpill.[324][325][326][327]

.JPG/440px-Los_Angeles_-_Echangeur_autoroute_110_105_(cropped).JPG)

The city and the rest of the Los Angeles metropolitan area are served by an extensive network of freeways and highways. Texas Transportation Institute's annual Urban Mobility Report ranked Los Angeles area roads the most congested in the United States in 2019 as measured by annual delay per traveler, area residents experiencing a cumulative average of 119 hours waiting in traffic that year.[328] Los Angeles was followed by San Francisco/Oakland, Washington, D.C., and Miami. Despite the congestion in the city, the mean daily travel time for commuters in Los Angeles is shorter than other major cities, including New York City, Philadelphia and Chicago. Los Angeles's mean travel time for work commutes in 2006 was 29.2 minutes, similar to those of San Francisco and Washington, D.C.[329]

The major highways that connect LA to the rest of the nation include Interstate 5, which runs south through San Diego to Tijuana in Mexico and north through Sacramento, Portland, and Seattle to the Canada–US border; Interstate 10, the southernmost east–west, coast-to-coast Interstate Highway in the United States, going to Jacksonville, Florida; and U.S. Route 101, which heads to the California Central Coast, San Francisco, the Redwood Empire, and the Oregon and Washington coasts.

The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LACMTA; branded as Metro) and other regional agencies provide a comprehensive bus system that covers Los Angeles County. While the Los Angeles Department of Transportation is responsible for contracting local and commuter bus services primarily within the city limits of Los Angeles and several immediate neighboring municipalities in southwest Los Angeles County,[330] the largest bus system in the city is operated by Metro.[331] Called Los Angeles Metro Bus, the system consists of 117 routes (excluding Metro Busway) throughout Los Angeles and neighboring cities primarily in southwestern Los Angeles County, with most routes following along a particular street in the city's street grid and run to or through Downtown Los Angeles.[332] As of the third quarter of 2023, the system had an average ridership of approximately 692,500 per weekday, with a total of 197,950,700 riders in 2022.[333] Metro also runs two Metro Busway lines, the G and J lines, which are bus rapid transit lines with stops and frequencies similar to those of Los Angeles's light rail system.

There are also smaller regional public transit systems that mainly serve specific cities or regions in Los Angeles County. For example, the Big Blue Bus provides extensive bus service in Santa Monica and western Los Angeles County, while Foothill Transit focuses on routes in the San Gabriel Valley in southeast Los Angeles County with one express route going into downtown Los Angeles. Los Angeles World Airports also runs two frequent FlyAway express bus routes (via freeways) from Los Angeles Union Station and Van Nuys to Los Angeles International Airport.[334]

While cash is accepted on all buses, the primary payment method for Los Angeles Metro Bus, Metro Busway, and 27 other regional bus agencies is a TAP card, a contactless stored-value card.[335] According to the 2016 American Community Survey, 9.2% of working Los Angeles (city) residents made the journey to work via public transportation.[336]

The Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority also operate a subway and light rail system across Los Angeles and its county. The system is called Los Angeles Metro Rail and consists of the B and D subway lines, as well as the A, C, E, and K light rail lines.[332] TAP cards are required for all Metro Rail trips.[337] As of the third quarter of 2023, the city's subway system is the ninth busiest in the United States, and its light rail system is the country's second busiest.[333] In 2022, the system had a ridership of 57,299,800, or about 189,200 per weekday, in the third quarter of 2023.[333]

Since the opening of the first line, the A Line, in 1990, the system has been extended significantly, with more extensions currently in progress. Today, the system serves numerous areas across the county on 107.4 mi (172.8 km) of rail, including Long Beach, Pasadena, Santa Monica, Norwalk, El Segundo, North Hollywood, Inglewood, and Downtown Los Angeles. As of 2023, there are 101 stations in the Metro Rail system.[338]

Los Angeles is also center of its county's commuter rail system, Metrolink, which links Los Angeles to Ventura, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and San Diego Counties. The system consists of eight lines and 69 stations operating on 545.6 miles (878.1 kilometres) of track.[339] Metrolink averages 42,600 trips per weekday, the busiest line being the San Bernardino Line.[340] Apart from Metrolink, Los Angeles is also connected to other cities by intercity passenger trains from Amtrak on five different lines.[341] One of the lines is the Pacific Surfliner route which operates multiple daily round trips between San Diego and San Luis Obispo, California through Union Station.[342] It is Amtrak's busiest line outside the Northeast Corridor.[343]

The main rail station in the city is Union Station which opened in 1939, and it is the largest passenger rail terminal in the Western United States.[344] The station is a major regional train station for Amtrak, Metrolink and Metro Rail. The station is Amtrak's fifth busiest station, having 1.4 million Amtrak boardings and de-boardings in 2019.[345] Union Station also offers access to Metro Bus, Greyhound, LAX FlyAway, and other buses from different agencies.[346]

.jpg/440px-TheThemeBuildingLosAngeles_(cropped2).jpg)

The main international and domestic airport serving Los Angeles is Los Angeles International Airport, commonly referred to by its airport code, LAX.[347] It is located on the Westside of Los Angeles near the Sofi Stadium in Inglewood.

Other major nearby commercial airports include:

One of the world's busiest general-aviation airports is also in Los Angeles: Van Nuys Airport.[351]

The Port of Los Angeles is in San Pedro Bay in the San Pedro neighborhood, approximately 20 miles (32 km) south of Downtown. Also called Los Angeles Harbor and WORLDPORT LA, the port complex occupies 7,500 acres (30 km2) of land and water along 43 miles (69 km) of waterfront. It adjoins the separate Port of Long Beach.[352]

The sea ports of the Port of Los Angeles and Port of Long Beach together make up the Los Angeles/Long Beach Harbor.[353][354] Together, both ports are the fifth busiest container port in the world, with a trade volume of over 14.2 million TEU's in 2008.[355] Singly, the Port of Los Angeles is the busiest container port in the United States and the largest cruise ship center on the West Coast of the United States – The Port of Los Angeles's World Cruise Center served about 590,000 passengers in 2014.[356]

There are also smaller, non-industrial harbors along Los Angeles's coastline. The port includes four bridges: the Vincent Thomas Bridge, Henry Ford Bridge, Long Beach International Gateway Bridge, and Commodore Schuyler F. Heim Bridge. Passenger ferry service from San Pedro to the city of Avalon (and Two Harbors) on Santa Catalina Island is provided by Catalina Express.

Los Angeles has 25 sister cities,[357] listed chronologically by year joined:

In addition, Los Angeles has the following "friendship cities":

The Native American name for Los Angeles was Yang na, which translates into "the valley of smoke."

Founded on the site of a Gabrielino Indian village called Yang-na, or iyáangẚ, 'poison-oak place.'

Los Angeles itself was built over a Gabrielino village called Yangna or iyaanga', 'poison oak place.'

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)