Европейский союз ( ЕС ) — наднациональное политическое и экономическое объединение 27 государств-членов , расположенных в основном в Европе. [8] [9] Общая площадь Союза составляет 4 233 255 км 2 (1 634 469 кв. миль), а общая численность населения оценивается в более чем 449 миллионов человек. ЕС часто описывается как политическое образование sui generis, сочетающее в себе характеристики как федерации , так и конфедерации . [10] [11]

Содержа 5,8% населения мира в 2020 году, [c] государства-члены ЕС создали номинальный валовой внутренний продукт (ВВП) в размере около 16,6 триллионов долларов США в 2022 году, что составляет примерно одну шестую часть мирового номинального ВВП . [13] Кроме того, все государства ЕС, за исключением Болгарии, имеют очень высокий Индекс развития человеческого потенциала по данным Программы развития Организации Объединенных Наций . Его краеугольный камень, Таможенный союз , проложил путь к созданию внутреннего единого рынка на основе стандартизированной правовой базы и законодательства , которое применяется во всех государствах-членах в тех вопросах, и только в тех вопросах, где государства согласились действовать как единое целое. Политика ЕС направлена на обеспечение свободного перемещения людей, товаров, услуг и капитала в рамках внутреннего рынка; [14] принятие законодательства в области правосудия и внутренних дел; и поддержание общей политики в области торговли , [15] сельского хозяйства , [16] рыболовства и регионального развития . [17] Паспортный контроль был отменен для поездок в пределах Шенгенской зоны . [18] Еврозона — это группа, состоящая из 20 государств-членов ЕС, которые полностью реализовали экономический и валютный союз и используют валюту евро . Благодаря Общей внешней политике и политике безопасности союз развил свою роль во внешних отношениях и обороне . Он поддерживает постоянные дипломатические миссии по всему миру и представляет себя в Организации Объединенных Наций , Всемирной торговой организации , G7 и G20 . Из-за своего глобального влияния Европейский союз был описан некоторыми учеными как зарождающаяся сверхдержава . [19] [20] [21]

ЕС был создан вместе со своим гражданством , когда Маастрихтский договор вступил в силу в 1993 году, и был включен в качестве международного юридического лица [ требуется разъяснение ] после вступления в силу Лиссабонского договора в 2009 году . [22] Его начало можно проследить до Внутренней шестерки государств (Бельгия, Франция, Италия, Люксембург, Нидерланды и Западная Германия ) в начале современной европейской интеграции в 1948 году, а также до Западного союза , Международного органа по Руру , Европейского объединения угля и стали , Европейского экономического сообщества и Европейского сообщества по атомной энергии , которые были созданы договорами. Эти все более объединенные органы росли, вместе со своим законным преемником ЕС, как по размеру за счет присоединения еще 22 государств с 1973 по 2013 год, так и по силе за счет приобретения политических сфер.

В 2012 году ЕС был удостоен Нобелевской премии мира . [23] Соединенное Королевство стало единственным государством-членом, покинувшим ЕС в 2020 году; [24] десять стран стремятся или ведут переговоры о присоединении к нему .

Интернационализм и видения европейского единства существовали задолго до 19 века, но особенно усилились как реакция на Первую мировую войну и ее последствия. В этом свете были сделаны первые шаги в пользу идеи европейской интеграции . В 1920 году Джон Мейнард Кейнс предложил создать Европейский таможенный союз для борющихся за послевоенную экономику европейских стран, [27] а в 1923 году была основана старейшая организация для европейской интеграции, Панъевропейский союз , во главе с Рихардом фон Куденхове-Калерги , который позже в июне 1947 года основал Европейский парламентский союз (ЕПС). Аристид Бриан — премьер-министр Франции , сторонник Панъевропейского союза и лауреат Нобелевской премии мира за Локарнские договоры — выступил с широко известной речью в Лиге Наций в Женеве 5 сентября 1929 года о федеральной Европе для обеспечения безопасности Европы и урегулирования исторической франко-германской вражды . [28] [29]

С крупномасштабной войной, которая снова велась в Европе в 1930-х годах и стала Второй мировой войной , необходимо было согласовать вопрос о том, против чего и за что бороться. Первым соглашением стала Декларация Сент-Джеймсского дворца 1941 года, когда сопротивление Европы собралось в Лондоне. Она была расширена Атлантической хартией 1941 года , установившей союзников и их общие цели, что вызвало новую волну глобальных международных институтов, таких как Организация Объединенных Наций ( основана в 1945 году ) или Бреттон-Вудская система (1944 год). [30]

В 1943 году на Московской конференции и Тегеранской конференции планы создания совместных институтов для послевоенного мира и Европы все больше становились частью повестки дня. Это привело к решению на Ялтинской конференции в 1944 году сформировать Европейскую консультативную комиссию , позже замененную Советом министров иностранных дел и Контрольным советом союзников после капитуляции Германии и Потсдамского соглашения в 1945 году.

К концу войны европейская интеграция стала рассматриваться как противоядие от крайнего национализма , который стал причиной войны. [31] 19 сентября 1946 года в широко известной речи Уинстон Черчилль , выступая в Цюрихском университете , повторил свои призывы с 1930 года к «Европейскому союзу» и «Совету Европы», по совпадению [32] параллельно [ необходимо разъяснение ] с Конгрессом Гертенштейна Союза европейских федералистов , [33] одного из тогда основанных и позднее учредительных членов Европейского движения . Месяц спустя Французский союз был создан новой Четвертой Французской Республикой для руководства деколонизацией своих колоний , чтобы они стали частями Европейского сообщества. [34]

К 1947 году растущий раскол между западными союзными державами и Советским Союзом стал очевиден в результате фальсификации польских законодательных выборов 1947 года , что представляло собой открытое нарушение Ялтинского соглашения . В марте того года произошло два важных события. Во-первых, было подписание Дюнкеркского договора между Францией и Соединенным Королевством . Договор гарантировал взаимную помощь в случае будущей военной агрессии против любой из стран. Хотя официально Германия была названа угрозой, на самом деле реальная проблема была в Советском Союзе. Несколько дней спустя было объявлено о доктрине Трумэна , которая обещала американскую поддержку демократий для противодействия Советам.

Сразу после государственного переворота, совершенного Коммунистической партией Чехословакии в феврале 1948 года , состоялась Лондонская конференция шести держав , в результате которой Советский Союз объявил бойкот Контрольному совету союзников и лишил его дееспособности, что ознаменовало начало холодной войны .

1948 год ознаменовал начало институционализированной современной европейской интеграции . В марте 1948 года был подписан Брюссельский договор , учредивший Западный союз (ЗС), за которым последовало Международное управление по Руру . Кроме того, Организация европейского экономического сотрудничества (ОЕЭС), предшественница ОЭСР, также была основана в 1948 году для управления планом Маршалла , что привело к созданию Советами СЭВ в ответ. Последующий Гаагский конгресс в мае 1948 года стал поворотным моментом в европейской интеграции, поскольку он привел к созданию Европейского международного движения , Колледжа Европы [35] и, что наиболее важно, к основанию Совета Европы 5 мая 1949 года (сейчас это День Европы ). Совет Европы был одним из первых институтов, объединивших суверенные государства (тогда только Западной) Европы, породив большие надежды и бурные дебаты в последующие два года по поводу дальнейшей европейской интеграции. [ необходима цитата ] С тех пор это был широкий форум для дальнейшего сотрудничества и общих проблем, достигнув, например, Европейской конвенции о правах человека в 1950 году. Существенное значение для фактического рождения институтов ЕС имела Декларация Шумана от 9 мая 1950 года (на следующий день после пятого Дня Победы в Европе ) и решение шести стран (Франция, Бельгия, Нидерланды, Люксембург, Западная Германия и Италия) последовать примеру Шумана и разработать Парижский договор . Этот договор был создан в 1952 году Европейским сообществом угля и стали (ЕОУС), которое было построено на Международном органе по Руру , созданном западными союзниками в 1949 году для регулирования угольной и сталелитейной промышленности Рурской области в Западной Германии. [36] Поддерживаемое планом Маршалла с крупными фондами, поступающими из Соединенных Штатов с 1948 года, ЕОУС стало знаковой организацией, обеспечивающей европейское экономическое развитие и интеграцию и являющейся источником основных институтов ЕС, таких как Европейская комиссия и Парламент . [37] Отцы-основатели Европейского Союза понимали, что уголь и сталь являются двумя отраслями промышленности, необходимыми для ведения войны, и считали, что, связав свои национальные отрасли промышленности вместе, будущая война между их странами станет гораздо менее вероятной. [38] Параллельно с Шуманом,План Плевена 1951 года пытался, но не смог связать институты развивающегося европейского сообщества в Европейское политическое сообщество , которое должно было включать также предложенное Европейское оборонительное сообщество , альтернативу вступлению Западной Германии в НАТО , которое было создано в 1949 году в соответствии с доктриной Трумэна . В 1954 году Измененный Брюссельский договор преобразовал Западный союз в Западноевропейский союз (ЗЕС). Западная Германия в конечном итоге присоединилась как к ЗЕС, так и к НАТО в 1955 году, что побудило Советский Союз сформировать Варшавский договор в 1955 году в качестве институциональной основы для своего военного господства в странах Центральной и Восточной Европы . Оценивая прогресс европейской интеграции, в 1955 году состоялась Мессинская конференция , заказавшая доклад Спаака , который в 1956 году рекомендовал следующие важные шаги европейской интеграции.

В 1957 году Бельгия , Франция , Италия , Люксембург , Нидерланды и Западная Германия подписали Римский договор , который создал Европейское экономическое сообщество (ЕЭС) и учредил таможенный союз . Они также подписали еще один пакт о создании Европейского сообщества по атомной энергии (Евратом) для сотрудничества в развитии ядерной энергетики. Оба договора вступили в силу в 1958 году. [38] Хотя ЕЭС и Евратом были созданы отдельно от ЕОУС, они имели одни и те же суды и Общую ассамблею. ЕЭС возглавлял Вальтер Хальштейн ( Комиссия Хальштейна ), а Евратом возглавлял Луи Арман ( Комиссия Армана ), а затем Этьен Хирш ( Комиссия Хирша ). [39] [40] ОЕЭС, в свою очередь, была преобразована в 1961 году в Организацию экономического сотрудничества и развития (ОЭСР), и ее членство было расширено на государства за пределами Европы, США и Канаду. В 1960-х годах начала проявляться напряженность, поскольку Франция стремилась ограничить наднациональную власть. Тем не менее, в 1965 году было достигнуто соглашение, и 1 июля 1967 года Договор о слиянии создал единый набор институтов для трех сообществ, которые в совокупности именовались Европейскими сообществами . [41] [42] Жан Рей председательствовал в первой объединенной комиссии ( Комиссии Рея ). [43]

В 1973 году сообщества были расширены за счет включения Дании (включая Гренландию), Ирландии и Соединенного Королевства . [44] Норвегия вела переговоры о присоединении в то же время, но норвежские избиратели отклонили членство на референдуме . Ostpolitik и последовавшая за этим разрядка привели к созданию первого по-настоящему общеевропейского органа, Конференции по безопасности и сотрудничеству в Европе (СБСЕ), предшественника современной Организации по безопасности и сотрудничеству в Европе (ОБСЕ). В 1979 году прошли первые прямые выборы в Европейский парламент. [45] Греция присоединилась в 1981 году. В 1985 году Гренландия вышла из Сообщества из-за спора о правах на рыбную ловлю. В том же году Шенгенское соглашение проложило путь к созданию открытых границ без паспортного контроля между большинством государств-членов и некоторыми государствами, не являющимися членами. [46] В 1986 году был подписан Единый европейский акт . Португалия и Испания присоединились в 1986 году. [47] В 1990 году, после распада Восточного блока , бывшая Восточная Германия вошла в состав сообществ как часть воссоединенной Германии . [48]

_(cropped).JPG/440px-GER_—_BY_—_Regensburg_-_Donaumarkt_1_(Museum_der_Bayerischen_Geschichte;_Vertrag_von_Maastricht)_(cropped).JPG)

Европейский союз был официально создан, когда Маастрихтский договор , главными архитекторами которого были Хорст Кёлер , [49] Гельмут Коль и Франсуа Миттеран, вступил в силу 1 ноября 1993 года. [22] [50] Договор также дал название Европейскому сообществу для ЕЭС, даже если оно так называлось до договора. С дальнейшим расширением, запланированным для включения бывших коммунистических государств Центральной и Восточной Европы, а также Кипра и Мальты , Копенгагенские критерии для кандидатов на вступление в ЕС были согласованы в июне 1993 года. Расширение ЕС внесло новый уровень сложности и разногласий. [51] В 1995 году к ЕС присоединились Австрия, Финляндия и Швеция .

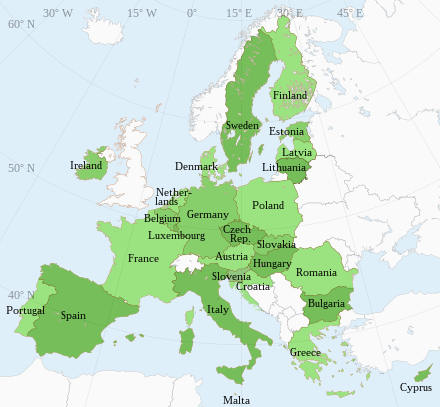

В 2002 году банкноты и монеты евро заменили национальные валюты в 12 странах-членах. С тех пор еврозона расширилась и теперь охватывает 20 стран. Евро стала второй по величине резервной валютой в мире. В 2004 году ЕС пережил самое крупное расширение на сегодняшний день, когда к союзу присоединились Кипр, Чешская Республика, Эстония , Венгрия , Латвия , Литва , Мальта , Польша , Словакия и Словения . [52]

.jpg/440px-Tratado_de_Lisboa_13_12_2007_(04).jpg)

В 2007 году членами ЕС стали Болгария и Румыния. Позже в том же году евро перешла Словения, [52] за ней последовали Кипр и Мальта в 2008 году, Словакия в 2009 году, Эстония в 2011 году, Латвия в 2014 году и Литва в 2015 году.

1 декабря 2009 года вступил в силу Лиссабонский договор , реформировавший многие аспекты ЕС. В частности, он изменил правовую структуру Европейского союза, объединив систему трех столпов ЕС в единое юридическое лицо, наделенное правосубъектностью , создал постоянного председателя Европейского совета , первым из которых стал Херман Ван Ромпей , и укрепил положение верховного представителя союза по иностранным делам и политике безопасности . [53] [54]

В 2012 году ЕС получил Нобелевскую премию мира за «вклад в продвижение мира и примирения, демократии и прав человека в Европе». [55] [56] В 2013 году Хорватия стала 28-м членом ЕС. [57]

С начала 2010-х годов сплоченность Европейского союза подвергалась испытанию несколькими проблемами, включая долговой кризис в некоторых странах еврозоны , всплеск числа просителей убежища в 2015 году и выход Соединенного Королевства из ЕС . [58] Референдум в Великобритании о ее членстве в Европейском союзе состоялся в 2016 году, и 51,9 процента участников проголосовали за выход. [59] Великобритания официально уведомила Европейский совет о своем решении выйти 29 марта 2017 года, инициировав формальную процедуру выхода из ЕС ; после продления процесса Великобритания вышла из Европейского союза 31 января 2020 года, хотя большинство областей права ЕС продолжали применяться к Великобритании в течение переходного периода, который продлился до 31 декабря 2020 года. [60]

В начале 2020-х годов Дания отменила один из трех вариантов выхода из системы , а Хорватия перешла на евро .

После экономического кризиса , вызванного пандемией COVID-19 , лидеры ЕС впервые согласились создать общий долг для финансирования Европейской программы восстановления под названием « Следующее поколение ЕС» (NGEU). [61]

24 февраля 2022 года, после сосредоточения на границах Украины, Вооруженные силы России предприняли попытку полномасштабного вторжения на Украину. [62] [63] Европейский союз ввел жесткие санкции против России и согласовал пакет объединенной военной помощи Украине в виде летального оружия, финансируемого через внебюджетный инструмент Европейского фонда мира . [64]

Next Generation EU ( NGEU ) — это пакет мер по экономическому восстановлению Европейской комиссии , призванный поддержать государства-члены ЕС в восстановлении после пандемии COVID-19 , в частности, те, которые особенно сильно пострадали. Иногда его называют NextGenerationEU и Next Gen EU , а также называют Инструментом восстановления Европейского союза . [65] В принципе одобренный Европейским советом 21 июля 2020 года и принятый 14 декабря 2020 года, инструмент оценивается в 750 миллиардов евро . NGEU будет действовать с 2021 по 2026 год [66] и будет привязан к регулярному бюджету Многолетней финансовой структуры ЕС (MFF) на 2021–2027 годы. Прогнозируется, что комплексные пакеты NGEU и MFF достигнут 1824,3 миллиарда евро. [67]

Подготовка Союза к новому большому расширению является политическим приоритетом Союза, с целью достижения более 35 государств-членов к 2030 году. Обсуждаются институциональные и бюджетные реформы, чтобы Союз был готов к новым членам. [68] [69] [70] [71]

В мае 2024 года растут опасения, что результаты выборов в июне могут подорвать некоторые из важнейших политик ЕС в области окружающей среды, дипломатии, экономики . Война на Украине, создав инфляцию, снизив уровень жизни, создала возможность серьезных изменений на выборах 2024 года. [72] [73]

После окончания Второй мировой войны суверенные европейские страны заключили договоры и тем самым сотрудничали и гармонизировали политику (или объединили суверенитет ) во все большем количестве областей, в европейском интеграционном проекте или строительстве Европы ( по-французски : la construction européenne ). Следующая временная шкала описывает юридическое начало Европейского Союза (ЕС) — основной структуры для этого объединения. ЕС унаследовал многие из своих нынешних обязанностей от Европейских сообществ (ЕС), которые были основаны в 1950-х годах в духе Декларации Шумана .

Европейский союз действует через гибридную систему наднационального и межправительственного принятия решений, [74] [75] и в соответствии с принципом передачи полномочий (который гласит, что он должен действовать только в пределах полномочий, предоставленных ему договорами ) и субсидиарности (который гласит, что он должен действовать только в тех случаях, когда цель не может быть в достаточной степени достигнута государствами-членами, действующими в одиночку). Законы, принимаемые институтами ЕС, принимаются в различных формах. [76] В целом их можно разделить на две группы: те, которые вступают в силу без необходимости принятия мер по национальной реализации (постановления), и те, которые конкретно требуют принятия мер по национальной реализации (директивы). [d]

Политика ЕС в целом провозглашается директивами ЕС , которые затем внедряются в национальное законодательство его государств-членов , и постановлениями ЕС , которые немедленно вступают в силу во всех государствах-членах. Лоббирование на уровне ЕС со стороны групп особых интересов регулируется, чтобы попытаться сбалансировать стремления частных инициатив с процессом принятия решений в интересах общественности. [77]

Европейский союз имел согласованный бюджет в размере €170,6 млрд в 2022 году. ЕС имел долгосрочный бюджет в размере €1,082.5 млрд на период 2014-2020 годов, что составляло 1,02% от ВНД ЕС-28. В 1960 году бюджет Европейского сообщества составлял 0,03% от ВВП. [79]

Из этой суммы 54 млрд евро было направлено на субсидирование сельскохозяйственных предприятий , 42 млрд евро было потрачено на транспорт , строительство и окружающую среду, 16 млрд евро на образование и исследования , 13 млрд евро на социальное обеспечение, 20 млрд евро на внешнюю и оборонную политику, 2 млрд евро на финансы , 2 млрд евро на энергетику , 1,5 млрд евро на связь и 13 млрд евро на администрирование.

В ноябре 2020 года два члена союза, Венгрия и Польша, заблокировали одобрение бюджета ЕС на заседании Комитета постоянных представителей (Coreper), сославшись на предложение, которое связывало финансирование с соблюдением верховенства закона . Бюджет включал фонд восстановления после COVID-19 в размере €750 млрд. Бюджет все еще может быть одобрен, если Венгрия и Польша снимут свои вето после дальнейших переговоров в совете и Европейском совете . [80] [81] [ требуется обновление ]

Также были созданы органы по борьбе с мошенничеством, включая Европейское бюро по борьбе с мошенничеством и Европейскую прокуратуру . Последняя является децентрализованным независимым органом Европейского союза (ЕС), созданным в соответствии с Лиссабонским договором между 22 из 27 государств ЕС в соответствии с методом расширенного сотрудничества . [82] Европейская прокуратура расследует и преследует мошенничество против бюджета Европейского союза и другие преступления против финансовых интересов ЕС, включая мошенничество в отношении фондов ЕС на сумму более 10 000 евро и трансграничные дела о мошенничестве с НДС , включающие ущерб свыше 10 миллионов евро.

Государства-члены в принципе сохраняют все полномочия, за исключением тех, которые они коллективно согласились делегировать Союзу в целом, хотя точное разграничение порой становилось предметом научных или юридических споров. [83] [84]

В некоторых областях члены предоставили Союзу исключительную компетенцию и исключительный мандат . Это области, в которых государства-члены полностью отказались от своей собственной возможности принимать законодательство. В других областях ЕС и его государства-члены разделяют компетенцию по принятию законов. Хотя оба могут принимать законы, государства-члены могут принимать законы только в той степени, в которой ЕС этого не делает. В других областях политики ЕС может только координировать, поддерживать и дополнять действия государств-членов, но не может принимать законы с целью гармонизации национальных законов. [85] То, что конкретная область политики попадает в определенную категорию компетенции, не обязательно указывает на то, какая законодательная процедура используется для принятия законодательства в этой области политики. Различные законодательные процедуры используются в одной и той же категории компетенции и даже в одной и той же области политики. Распределение компетенций в различных областях политики между государствами-членами и союзом делится на следующие три категории:

Европейский союз имеет семь основных органов принятия решений, его институтов : Европейский парламент , Европейский совет , Совет Европейского союза , Европейская комиссия , Суд Европейского союза , Европейский центральный банк и Европейская счетная палата . Компетенция по проверке и внесению поправок в законодательство разделена между Советом Европейского союза и Европейским парламентом, в то время как исполнительные задачи выполняются Европейской комиссией и в ограниченных полномочиях Европейским советом (не путать с вышеупомянутым Советом Европейского союза). Денежно-кредитная политика еврозоны определяется Европейским центральным банком. Толкование и применение права ЕС и договоров обеспечиваются Судом Европейского союза. Бюджет ЕС проверяется Европейской счетной палатой. Существует также ряд вспомогательных органов, которые консультируют ЕС или действуют в определенной области.

Исполнительная власть Союза организована как директорская система , где исполнительная власть осуществляется совместно несколькими лицами. Исполнительная власть состоит из Европейского совета и Европейской комиссии.

Европейский совет устанавливает общее политическое направление Союза. Он собирается не реже четырех раз в год и состоит из президента Европейского совета (в настоящее время Шарля Мишеля ), президента Европейской комиссии и одного представителя от каждого государства-члена (либо главы государства , либо главы правительства ). Верховный представитель союза по иностранным делам и политике безопасности (в настоящее время Жозепа Борреля ) также принимает участие в его заседаниях. Описанный некоторыми как «высшее политическое руководство» союза, [87] он активно участвует в переговорах об изменениях в договорах и определяет политическую повестку дня и стратегии ЕС. Его руководящая роль включает разрешение споров между государствами-членами и институтами, а также разрешение любых политических кризисов или разногласий по спорным вопросам и политике. Он действует как « коллективный глава государства » и ратифицирует важные документы (например, международные соглашения и договоры). [88] Задачи президента Европейского совета — обеспечение внешнего представительства ЕС, [89] достижение консенсуса и разрешение разногласий между государствами-членами как во время заседаний Европейского совета, так и в периоды между ними. Европейский совет не следует путать с Советом Европы , международной организацией, независимой от ЕС и базирующейся в Страсбурге.

Европейская комиссия действует как исполнительный орган ЕС , отвечающий за повседневное управление ЕС, а также законодательный инициатор , имеющий исключительное право предлагать законы для обсуждения. [90] [91] [92] Комиссия является «хранителем договоров» и отвечает за их эффективное функционирование и контроль. [93] В ее состав входят 27 европейских комиссаров по различным направлениям политики, по одному от каждого государства-члена, хотя комиссары обязаны представлять интересы ЕС в целом, а не своего государства. Лидером 27 является президент Европейской комиссии (в настоящее время Урсула фон дер Ляйен на 2019–2024 годы), кандидатура которого предлагается Европейским советом с учетом результатов европейских выборов, а затем он избирается Европейским парламентом. [94] Президент сохраняет за собой, как лидер, ответственный за весь кабинет, последнее слово в принятии или отклонении кандидата, представленного на данный портфель государством-членом, и контролирует постоянную государственную службу комиссии. После президента наиболее видным комиссаром является верховный представитель союза по иностранным делам и политике безопасности, который по должности является вице -президентом Европейской комиссии и также выбирается Европейским советом. [95] Остальные 25 комиссаров впоследствии назначаются Советом Европейского союза по согласованию с назначенным президентом. 27 комиссаров как единый орган подлежат утверждению (или иному) голосованием Европейского парламента . Все комиссары сначала назначаются правительством соответствующего государства-члена. [96]

Совет, как он теперь просто называется [97] (также называемый Советом Европейского Союза [98] и «Советом министров», его прежнее название), [99] образует половину законодательного органа ЕС. Он состоит из представителя правительства каждого государства-члена и собирается в разных составах в зависимости от рассматриваемой области политики . Несмотря на его различные конфигурации, он считается единым органом. В дополнение к законодательным функциям члены совета также имеют исполнительные обязанности, такие как разработка общей внешней политики и политики безопасности и координация широкой экономической политики в рамках Союза. [100] Председательство в совете поочередно переходит от одного государства-члена к другому, каждое из которых занимает его в течение шести месяцев. Начиная с 1 июля 2024 года эту должность занимает Венгрия. [101]

Европейский парламент является одним из трех законодательных органов ЕС, который вместе с Советом Европейского союза уполномочен вносить поправки и утверждать предложения Европейской комиссии. 705 членов Европейского парламента (MEP) избираются гражданами ЕС напрямую каждые пять лет на основе пропорционального представительства . Депутаты избираются на национальной основе и заседают в соответствии с политическими группами, а не по своей национальности. Каждая страна имеет установленное количество мест и разделена на субнациональные избирательные округа , где это не влияет на пропорциональный характер системы голосования. [102] В обычной законодательной процедуре Европейская комиссия предлагает законодательство, которое требует совместного одобрения Европейского парламента и Совета Европейского союза для принятия. Этот процесс применяется почти ко всем областям, включая бюджет ЕС . Парламент является окончательным органом, который утверждает или отклоняет предлагаемый состав комиссии, и может попытаться вынести вотум недоверия комиссии путем апелляции в Суд . Председатель Европейского парламента выполняет роль спикера в парламенте и представляет его за его пределами. Президент и вице-президенты избираются членами Европарламента каждые два с половиной года. [103]

Судебная ветвь Европейского Союза официально называется Судом Европейского Союза (CJEU) и состоит из двух судов: Суда и Общего суда . [104] Суд является верховным судом Европейского Союза по вопросам права Европейского Союза . Как часть CJEU, он занимается толкованием права ЕС и обеспечением его единообразного применения во всех государствах - членах ЕС в соответствии со статьей 263 Договора о функционировании Европейского Союза (TFEU). Суд был создан в 1952 году и базируется в Люксембурге . В его состав входит по одному судье от каждого государства-члена — в настоящее время их 27 — хотя обычно он рассматривает дела в составе трех, пяти или пятнадцати судей. С 2015 года Суд возглавляет президент Коэн Ленертс . CJEU является высшим судом Европейского Союза по вопросам права Союза . Его прецедентное право предусматривает, что право ЕС имеет верховенство над любым национальным законом, который не соответствует праву ЕС. [105] Невозможно обжаловать решения национальных судов в Суде Европейского союза, а национальные суды передают вопросы права ЕС в Суд Европейского союза. Однако в конечном итоге именно национальный суд должен применить полученное толкование к фактам любого конкретного дела. Хотя только суды последней инстанции обязаны передавать вопрос права ЕС, когда он рассматривается. Договоры предоставляют Суду Европейского союза полномочия для последовательного применения права ЕС по всему ЕС в целом. Суд также действует как административный и конституционный суд между другими институтами ЕС и государствами-членами и может аннулировать или признать недействительными незаконные акты институтов, органов, учреждений и агентств ЕС.

Генеральный суд является учредительным судом Европейского союза. Он рассматривает иски, поданные против институтов Европейского союза отдельными лицами и государствами-членами, хотя некоторые вопросы зарезервированы для Суда. Решения Генерального суда могут быть обжалованы в Суде, но только по вопросам права. До вступления в силу Лиссабонского договора 1 декабря 2009 года он был известен как Суд первой инстанции.

Европейский центральный банк (ЕЦБ) является одним из институтов денежно-кредитной отрасли Европейского союза, основным компонентом Евросистемы и Европейской системы центральных банков. Это один из важнейших центральных банков мира . Совет управляющих ЕЦБ разрабатывает денежно-кредитную политику для Еврозоны и Европейского союза, управляет валютными резервами государств-членов ЕС, участвует в валютных операциях и определяет промежуточные денежно-кредитные цели и ключевую процентную ставку ЕС. Исполнительный совет ЕЦБ обеспечивает соблюдение политики и решений Совета управляющих и может давать указания национальным центральным банкам при этом. ЕЦБ имеет исключительное право разрешать выпуск банкнот евро . Государства-члены могут выпускать монеты евро , но объем должен быть предварительно одобрен ЕЦБ. Банк также управляет платежной системой TARGET2 . Европейская система центральных банков (ЕСЦБ) состоит из ЕЦБ и национальных центральных банков (НЦБ) всех 27 государств-членов Европейского союза. ЕСЦБ не является денежно-кредитным органом еврозоны, поскольку не все государства-члены ЕС присоединились к евро. Целью ЕСЦБ является ценовая стабильность во всем Европейском союзе. Во-вторых, целью ЕСЦБ является улучшение денежно-кредитного и финансового сотрудничества между Евросистемой и государствами-членами за пределами еврозоны.

Европейская счетная палата (ECA) является аудиторским органом Европейского союза. Она была создана в 1975 году в Люксембурге с целью улучшения финансового управления ЕС. В ее состав входят 27 членов (по одному от каждого государства-члена ЕС), которым оказывают поддержку около 800 государственных служащих. Европейское бюро по отбору персонала (EPSO) является органом по набору на государственную службу ЕС и осуществляет отбор кандидатов посредством конкурсов на должности общего и специализированного профиля. Затем каждое учреждение может набирать персонал из числа кандидатов, отобранных EPSO. В среднем EPSO получает около 60 000–70 000 заявлений в год, при этом около 1500–2000 кандидатов набираются учреждениями Европейского союза. Европейский омбудсмен является ветвью омбудсмена Европейского союза, которая контролирует деятельность учреждений, органов и агентств ЕС и содействует хорошему администрированию. Омбудсмен помогает людям, предприятиям и организациям, сталкивающимся с проблемами с администрацией ЕС, расследуя жалобы, а также активно изучая более широкие системные вопросы. Действующим омбудсменом является Эмили О'Рейли . Европейская прокуратура (ЕППО) является прокурорской ветвью союза с юридической правосубъектностью, созданной в соответствии с Лиссабонским договором между 23 из 27 государств ЕС в соответствии с методом расширенного сотрудничества. Она находится в Кирхберге, Люксембург, рядом с Судом Европейского союза и Европейской счетной палатой.

Конституционно ЕС имеет некоторое сходство как с конфедерацией , так и с федерацией , [ 106] [107] но формально не определил себя ни как одно из них. (У него нет формальной конституции: его статус определяется Договором о Европейском Союзе и Договором о функционировании Европейского Союза ). Он более интегрирован, чем традиционная конфедерация государств, поскольку общий уровень правительства широко использует квалифицированное большинство голосов при принятии некоторых решений среди государств-членов, а не полагается исключительно на единогласие. [108] [109] Он менее интегрирован, чем федеративное государство, поскольку он не является государством в своем собственном праве: суверенитет продолжает течь «снизу вверх», от нескольких народов отдельных государств-членов, а не от единого недифференцированного целого. Это отражается в том факте, что государства-члены остаются «хозяевами Договоров», сохраняя контроль над распределением полномочий в союзе посредством конституционных изменений (таким образом сохраняя так называемые Kompetenz-kompetenz ); в том, что они сохраняют контроль над использованием вооруженной силы; они сохраняют контроль над налогообложением; и в том, что они сохраняют право одностороннего выхода в соответствии со статьей 50 Договора о Европейском Союзе. Кроме того, принцип субсидиарности требует , чтобы только те вопросы, которые должны быть определены коллективно, были определены таким образом.

В соответствии с принципом верховенства национальные суды обязаны обеспечивать соблюдение договоров, ратифицированных их государствами-членами, даже если это требует от них игнорировать противоречащее им национальное законодательство и (в определенных пределах) даже конституционные положения. [e] Доктрины прямого действия и верховенства не были прямо изложены в Европейских договорах, но были разработаны самим Судом в 1960-х годах, по-видимому, под влиянием его самого влиятельного на тот момент судьи, француза Робера Лекура . [110] Вопрос о том, имеет ли вторичное право, принятое ЕС, сопоставимый статус по отношению к национальному законодательству, является предметом споров среди ученых-юристов.

Европейский союз основан на серии договоров . Сначала они создали Европейское сообщество и ЕС, а затем внесли поправки в эти учредительные договоры. [111] Это договоры, дающие полномочия, которые устанавливают широкие политические цели и создают институты с необходимыми юридическими полномочиями для реализации этих целей. Эти юридические полномочия включают возможность принимать законодательство [f] , которое может напрямую влиять на все государства-члены и их жителей. [g] ЕС имеет правосубъектность , с правом подписывать соглашения и международные договоры. [112]

Основные правовые акты Европейского Союза существуют в трех формах: регламенты , директивы и решения . Регламенты становятся законом во всех государствах-членах с момента вступления в силу, без необходимости принятия каких-либо мер по реализации, [h] и автоматически отменяют противоречащие им внутренние положения. [f] Директивы требуют от государств-членов достижения определенного результата, оставляя им свободу усмотрения относительно того, как достичь результата. Детали того, как они должны быть реализованы, оставлены на усмотрение государств-членов. [i] Когда срок действия директив по реализации истекает, они могут при определенных условиях иметь прямое действие в национальном законодательстве против государств-членов. Решения предлагают альтернативу двум вышеуказанным режимам законодательства. Это правовые акты, которые применяются только к определенным лицам, компаниям или конкретному государству-члену. Чаще всего они используются в законодательстве о конкуренции или в постановлениях о государственной помощи, но также часто используются для процедурных или административных вопросов в рамках учреждений. Регламенты, директивы и решения имеют одинаковую юридическую силу и применяются без какой-либо формальной иерархии. [113]

Внешнеполитическое сотрудничество между государствами-членами берет свое начало с момента создания сообщества в 1957 году, когда государства-члены вели переговоры как блок в международных торговых переговорах в рамках общей торговой политики ЕС . [114] Шаги к более широкой координации в международных отношениях начались в 1970 году с созданием Европейского политического сотрудничества , которое создало неформальный процесс консультаций между государствами-членами с целью формирования общей внешней политики. В 1987 году Европейское политическое сотрудничество было введено на формальной основе Единым европейским актом . Маастрихтским договором ЕПС было переименовано в Общую внешнюю политику и политику безопасности (ОВПБ) . [115]

Заявленные цели CFSP заключаются в содействии как собственным интересам ЕС, так и интересам международного сообщества в целом, включая содействие международному сотрудничеству, уважению прав человека, демократии и верховенству закона. [116] CFSP требует единогласия среди государств-членов относительно соответствующей политики, которой необходимо следовать по любому конкретному вопросу. Единогласие и сложные вопросы, рассматриваемые в рамках CFSP, иногда приводят к разногласиям, например, тем, которые возникли из-за войны в Ираке . [117]

Координатором и представителем CFSP в ЕС является верховный представитель союза по иностранным делам и политике безопасности , который выступает от имени ЕС по вопросам внешней политики и обороны и имеет задачу формулирования позиций, выраженных государствами-членами по этим областям политики, в общее выравнивание. Верховный представитель возглавляет Европейскую службу внешних действий (EEAS), уникальный департамент ЕС [118] , который был официально внедрен и функционирует с 1 декабря 2010 года по случаю первой годовщины вступления в силу Лиссабонского договора . [119] EEAS выполняет функции министерства иностранных дел и дипломатического корпуса для Европейского союза. [120]

Помимо формирующейся международной политики Европейского Союза, международное влияние ЕС также ощущается через расширение . Ощущаемые выгоды от вступления в ЕС действуют как стимул для политических и экономических реформ в государствах, желающих соответствовать критериям вступления в ЕС, и считаются важным фактором, способствующим реформированию бывших коммунистических стран Европы. [121] : 762 Это влияние на внутренние дела других стран обычно называют « мягкой силой », в отличие от военной «жесткой силы». [122]

Департамент гуманитарной помощи и гражданской защиты Европейской комиссии , или «ECHO», предоставляет гуманитарную помощь от ЕС развивающимся странам . В 2012 году его бюджет составил €874 млн, 51 процент бюджета был направлен в Африку, 20 процентов — в Азию, Латинскую Америку, Карибский бассейн и Тихоокеанский регион, и 20 процентов — на Ближний Восток и Средиземноморье. [123]

Гуманитарная помощь финансируется напрямую из бюджета (70 процентов) как часть финансовых инструментов для внешних действий, а также из Европейского фонда развития (30 процентов). [124] Финансирование внешних действий ЕС делится на «географические» инструменты и «тематические» инструменты. [124] «Географические» инструменты предоставляют помощь через Инструмент сотрудничества в целях развития (DCI, 16,9 млрд евро, 2007–2013 гг.), который должен тратить 95 процентов своего бюджета на официальную помощь в целях развития (ODA), и из Европейского инструмента соседства и партнерства (ENPI), который содержит некоторые соответствующие программы. [124] Европейский фонд развития (ЕФР, 22,7 млрд евро на период 2008–2013 гг. и 30,5 млрд евро на период 2014–2020 гг.) состоит из добровольных взносов государств-членов, но существует давление с целью объединения ЕФР с финансируемыми из бюджета инструментами, чтобы стимулировать увеличение взносов для достижения целевого показателя в 0,7% и предоставить Европейскому парламенту больший контроль. [124] [125]

В 2016 году средний показатель среди стран ЕС составил 0,4%, а пять стран достигли или превысили целевой показатель в 0,7%: Дания, Германия, Люксембург, Швеция и Великобритания. [126]

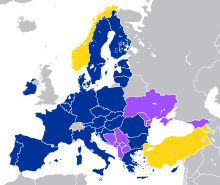

Европейский союз использует инструменты внешних сношений, такие как Европейская политика соседства , которая стремится привязать страны к востоку и югу от европейской территории ЕС к союзу. Эти страны, в первую очередь развивающиеся страны, включают в себя некоторые из тех, кто стремится в один прекрасный день стать либо государством-членом Европейского союза , либо более тесно интегрироваться с Европейским союзом. ЕС предлагает финансовую помощь странам в рамках Европейского соседства, если они соответствуют строгим условиям правительственной реформы, экономической реформы и другим вопросам, связанным с позитивной трансформацией. Этот процесс обычно подкрепляется Планом действий, согласованным как Брюсселем, так и целевой страной.

Существует также всемирная Глобальная стратегия Европейского союза . Международное признание устойчивого развития как ключевого элемента неуклонно растет. Его роль была признана на трех крупных саммитах ООН по устойчивому развитию: Конференция ООН по окружающей среде и развитию 1992 года в Рио-де-Жанейро, Бразилия; Всемирный саммит по устойчивому развитию 2002 года в Йоханнесбурге, Южная Африка ; и Конференция ООН по устойчивому развитию 2012 года в Рио-де-Жанейро. Другими ключевыми глобальными соглашениями являются Парижское соглашение и Повестка дня в области устойчивого развития на период до 2030 года (Организация Объединенных Наций, 2015). ЦУР признают, что все страны должны стимулировать действия в следующих ключевых областях — люди, планета , процветание, мир и партнерство — для решения глобальных проблем, которые имеют решающее значение для выживания человечества .

Действия ЕС по развитию основаны на Европейском консенсусе по развитию, который был одобрен 20 декабря 2005 года государствами-членами ЕС, советом, Европейским парламентом и комиссией. [127] Он применяется на основе принципов подхода, основанного на возможностях , и подхода, основанного на правах, к развитию . Финансирование осуществляется Инструментом помощи перед вступлением и программами Глобальной Европы .

Соглашения о партнерстве и сотрудничестве являются двусторонними соглашениями со странами, не являющимися членами. [128]

Предшественники Европейского союза не были задуманы как военный союз, поскольку НАТО в значительной степени рассматривалось как подходящее и достаточное для целей обороны. [129] 23 члена ЕС являются членами НАТО, в то время как остальные государства-члены придерживаются политики нейтралитета . [130] Западноевропейский союз , военный союз с положением о взаимной обороне, закрылся в 2011 году [131], поскольку его роль была передана ЕС. [132] После войны в Косово в 1999 году Европейский совет согласился, что «Союз должен иметь возможность для автономных действий, подкрепленных надежными военными силами, средствами для принятия решения об их использовании и готовностью делать это, чтобы реагировать на международные кризисы без ущерба для действий НАТО». С этой целью был предпринят ряд усилий по повышению военного потенциала ЕС, в частности, процесс «Главные цели Хельсинки » . После долгих обсуждений наиболее конкретным результатом стала инициатива боевых групп ЕС , каждая из которых, как планируется, сможет быстро развернуть около 1500 человек личного состава. [133] Стратегический компас ЕС, принятый в 2022 году, подтвердил партнерство блока с НАТО, нацеленное на повышение военной мобильности и формирование Сил быстрого развертывания ЕС численностью 5000 человек [134]

После выхода Соединенного Королевства Франция стала единственным членом, официально признанным государством, обладающим ядерным оружием , и единственным обладателем постоянного места в Совете Безопасности ООН . Франция и Италия также являются единственными странами ЕС, имеющими возможности проецирования силы за пределами Европы. [135] Италия, Германия, Нидерланды и Бельгия участвуют в ядерном обмене НАТО . [136] Большинство государств-членов ЕС выступили против Договора о запрещении ядерного оружия . [137]

Силы ЕС были развернуты в миротворческих миссиях от Центральной и Северной Африки до Западных Балкан и Западной Азии. [138] Военные операции ЕС поддерживаются рядом органов, включая Европейское оборонное агентство , Спутниковый центр Европейского союза и Военный штаб Европейского союза . [139] Военный штаб Европейского союза является высшим военным институтом Европейского союза, созданным в рамках Европейского совета и вытекающим из решений Хельсинкского Европейского совета (10–11 декабря 1999 г.), которые призвали к созданию постоянных политико-военных институтов. Военный штаб Европейского союза находится под руководством Верховного представителя Союза по иностранным делам и политике безопасности и Комитета по политике и безопасности. Он руководит всей военной деятельностью в контексте ЕС, включая планирование и проведение военных миссий и операций в рамках Общей политики безопасности и обороны и развитие военного потенциала, а также предоставляет Комитету по политике и безопасности военные консультации и рекомендации по военным вопросам. В ЕС, состоящем из 27 членов, существенное сотрудничество в области безопасности и обороны все больше зависит от взаимодействия между всеми государствами-членами. [140]

Европейское агентство пограничной и береговой охраны ( Frontex ) является агентством ЕС , целью которого является обнаружение и прекращение нелегальной иммиграции, торговли людьми и проникновения террористов. [141] ЕС также управляет Европейской системой информации и авторизации путешествий , Системой въезда/выезда , Шенгенской информационной системой , Системой визовой информации и Общей европейской системой предоставления убежища , которые предоставляют общие базы данных для полиции и иммиграционных властей. Стимулом к развитию этого сотрудничества стало появление открытых границ в Шенгенской зоне и связанная с этим трансграничная преступность. [18]

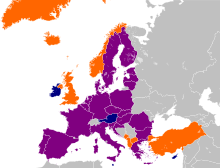

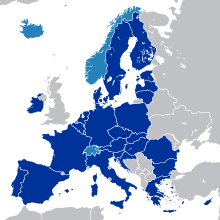

В результате последовательных расширений ЕС и его предшественники выросли из шести государств-основателей ЕЭС до 27 членов. Страны присоединяются к союзу, становясь участниками учредительных договоров , тем самым подчиняясь привилегиям и обязательствам членства в ЕС. Это влечет за собой частичное делегирование суверенитета институтам в обмен на представительство в этих институтах, практику, часто называемую «объединением суверенитета». [142] [143] В некоторых политиках есть несколько государств-членов, которые объединяются со стратегическими партнерами в рамках союза. Примерами таких альянсов являются Балтийская ассамблея , Союз Бенилюкса , Бухарестская девятка , Группа Крайова , Группа ЕС-Мед , Люблинский треугольник , Новый Ганзейский союз , Инициатива трех морей , Вышеградская группа и Веймарский треугольник .

Чтобы стать членом, страна должна соответствовать Копенгагенским критериям , определенным на заседании Европейского совета в Копенгагене в 1993 году. Они требуют стабильной демократии, которая уважает права человека и верховенство закона ; функционирующей рыночной экономики ; и принятия обязательств членства, включая законодательство ЕС. Оценка выполнения страной критериев является обязанностью Европейского совета . [144]

Четыре страны, входящие в Европейскую ассоциацию свободной торговли (ЕАСТ), не являются членами ЕС, но частично привержены экономике и правилам ЕС: Исландия, Лихтенштейн и Норвегия, которые являются частью единого рынка через Европейскую экономическую зону , и Швейцария , которая имеет аналогичные связи через двусторонние договоры . [145] [146] Отношения европейских микрогосударств Андорра , Монако , Сан-Марино и Ватикан включают использование евро и другие области сотрудничества. [147]

Подразделения государств-членов основаны на Номенклатуре территориальных единиц для статистики (NUTS), стандарте геокодирования для статистических целей. Стандарт , принятый в 2003 году, разработан и регулируется Европейским союзом и, таким образом, охватывает только государства-члены ЕС в деталях. Номенклатура территориальных единиц для статистики играет важную роль в механизмах поставок структурных фондов и фонда сплочения Европейского союза, а также для определения территории, на которую должны поставляться товары и услуги, подпадающие под европейское законодательство о государственных закупках .

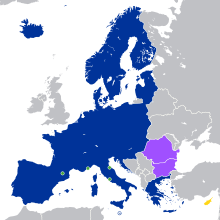

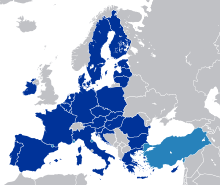

The Schengen Area is an area comprising 27 European countries that have officially abolished all passport and all other types of border control at their mutual borders. Being an element within the wider area of freedom, security and justice policy of the EU, it mostly functions as a single jurisdiction under a common visa policy for international travel purposes. The area is named after the 1985 Schengen Agreement and the 1990 Schengen Convention, both signed in Schengen, Luxembourg. Of the 27 EU member states, 25 participate in the Schengen Area, although two—Bulgaria, and Romania— are currently only partial members. Of the EU members that are not part of the Schengen Area, one—Cyprus—is legally obligated to join the area in the future; Ireland maintains an opt-out, and instead operates its own visa policy. The four European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member states, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, are not members of the EU, but have signed agreements in association with the Schengen Agreement. Also, three European microstates - Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City - maintain open borders for passenger traffic with their neighbours, and are therefore considered de facto members of the Schengen Area due to the practical impossibility of travelling to or from them without transiting through at least one Schengen member country.

There are nine countries that are recognised as candidates for membership: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey, and Ukraine.[149][150][151][152][153] Norway, Switzerland and Iceland have submitted membership applications in the past, but subsequently frozen or withdrawn them.[154] Additionally Kosovo is officially recognised as a potential candidate,[149][155] and submitted a membership application.[156]

Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty provides the basis for a member to leave the EU. Two territories have left the union: Greenland (an autonomous province of Denmark) withdrew in 1985;[157] the United Kingdom formally invoked Article 50 of the Consolidated Treaty on European Union in 2017, and became the only sovereign state to leave when it withdrew from the EU in 2020.

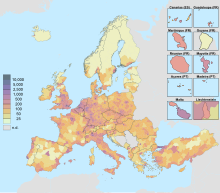

The EU's member states cover an area of 4,233,262 square kilometres (1,634,472 sq mi),[l] and therefore a large part of the European continent. The EU's highest peak is Mont Blanc in the Graian Alps, 4,810.45 metres (15,782 ft) above sea level.[158] The lowest points in the EU are Lammefjorden, Denmark, and Zuidplaspolder, Netherlands, at 7 m (23 ft) below sea level.[159] The landscape, climate, and economy of the EU are influenced by its coastline, which is 65,993 kilometres (41,006 mi) long.

In addition to national territories in Europe, there are 32 special territories of members of the European Economic Area, not all of which are part of the EU. The largest by area is Greenland, which is not part of the EU but whose citizens are EU citizens, while the largest by population are the Canary Islands off Africa, which are part of the EU and the Schengen area. French Guiana in South America is part of the EU and the Eurozone, as is Mayotte, north of Madagascar.

The climate of the European Union is of a temperate, continental nature, with a maritime climate prevailing on the western coasts and a mediterranean climate in the south. The climate is strongly conditioned by the Gulf Stream, which warms the western region to levels unattainable at similar latitudes on other continents. Western Europe is oceanic, while eastern Europe is continental and dry. Four seasons occur in western Europe, while southern Europe experiences a wet season and a dry season. Southern Europe is hot and dry during the summer months. The heaviest precipitation occurs downwind of water bodies due to the prevailing westerlies, with higher amounts also seen in the Alps.

In 1957, when the European Economic Community was founded, it had no environmental policy.[161] Over the past 50 years, an increasingly dense network of legislation has been created, extending to all areas of environmental protection, including air pollution, water quality, waste management, nature conservation, and the control of chemicals, industrial hazards, and biotechnology.[161] According to the Institute for European Environmental Policy, environmental law comprises over 500 Directives, Regulations and Decisions, making environmental policy a core area of European politics.[162]

European policy-makers originally increased the EU's capacity to act on environmental issues by defining it as a trade problem.[161] Trade barriers and competitive distortions in the Common Market could emerge due to the different environmental standards in each member state.[163] In subsequent years, the environment became a formal policy area, with its own policy actors, principles and procedures. The legal basis for EU environmental policy was established with the introduction of the Single European Act in 1987.[162]

Initially, EU environmental policy focused on Europe. More recently, the EU has demonstrated leadership in global environmental governance, e.g. the role of the EU in securing the ratification and coming into force of the Kyoto Protocol despite opposition from the United States. This international dimension is reflected in the EU's Sixth Environmental Action Programme,[164] which recognises that its objectives can only be achieved if key international agreements are actively supported and properly implemented both at EU level and worldwide. The Lisbon Treaty further strengthened the leadership ambitions.[161] EU law has played a significant role in improving habitat and species protection in Europe, as well as contributing to improvements in air and water quality and waste management.[162]

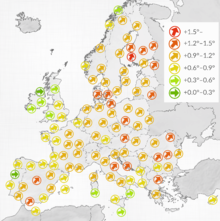

Mitigating climate change is one of the top priorities of EU environmental policy. In 2007, member states agreed that, in the future, 20 per cent of the energy used across the EU must be renewable, and carbon dioxide emissions have to be lower in 2020 by at least 20 per cent compared to 1990 levels.[165] In 2017, the EU emitted 9.1 per cent of global greenhouse-gas emissions.[166] The European Union claims that already in 2018, its GHG emissions were 23% lower than in 1990.[167]

The EU has adopted an emissions trading system to incorporate carbon emissions into the economy.[168] The European Green Capital is an annual award given to cities that focuses on the environment, energy efficiency, and quality of life in urban areas to create smart city. In the 2019 elections to the European Parliament, the green parties increased their power, possibly because of the rise of post materialist values.[169] Proposals to reach a zero carbon economy in the European Union by 2050 were suggested in 2018 – 2019. Almost all member states supported that goal at an EU summit in June 2019. The Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, and Poland disagreed.[170] In June 2021, the European Union passed a European Climate Law with targets of 55% GHG emissions reduction by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2050.[171] Also in the same year, the European Union and the United States pledged to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030. The pledge is considered as a big achievement for climate change mitigation.[172]

The gross domestic product (GDP), a measure of economic activity, of EU member states was US$16.64 trillion in 2022, around 16.6 percent of the world GDP.[173] There is a significant variation in GDP per capita between and within individual EU states. The difference between the richest and poorest regions (281 NUTS-2 regions of the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) ranged, in 2017, from 31 per cent (Severozapaden, Bulgaria) of the EU28 average (€30,000) to 253 per cent (Luxembourg), or from €4,600 to €92,600.[174]

EU member states own the estimated third largest after the United States (US$140 trillion) and China (US$84 trillion) net wealth in the world, equal to around one sixth (US$76 trillion) of the US$454 trillion global wealth.[175] Of the top 500 largest corporations in the world measured by revenue in 2010, 161 had their headquarters in the EU.[176] In 2016, unemployment in the EU stood at 8.9 per cent[177] while inflation was at 2.2 per cent, and the account balance at −0.9 per cent of GDP. The average annual net earnings in the European Union was around €25,000[178] in 2021.

The Euro is the official currency in 20 member states of the EU. The creation of a European single currency became an official objective of the European Economic Community in 1969. In 1992, having negotiated the structure and procedures of a currency union, the member states signed the Maastricht Treaty and were legally bound to fulfil the agreed-on rules including the convergence criteria if they wanted to join the monetary union. The states wanting to participate had first to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. To prevent the joining states from getting into financial trouble or crisis after entering the monetary union, they were obliged in the Maastricht treaty to fulfil important financial obligations and procedures, especially to show budgetary discipline and a high degree of sustainable economic convergence, as well as to avoid excessive government deficits and limit the government debt to a sustainable level, as agreed in the European Fiscal Pact.

Free movement of capital is intended to permit movement of investments such as property purchases and buying of shares between countries.[179] Until the drive towards economic and monetary union the development of the capital provisions had been slow. Post-Maastricht there has been a rapidly developing corpus of ECJ judgements regarding this initially neglected freedom. The free movement of capital is unique insofar as it is granted equally to non-member states.

The European System of Financial Supervision is an institutional architecture of the EU's framework of financial supervision composed by three authorities: the European Banking Authority, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority and the European Securities and Markets Authority. To complement this framework, there is also a European Systemic Risk Board under the responsibility of the central bank. The aim of this financial control system is to ensure the economic stability of the EU.[180]

In 1999, the currency union started to materialise through introducing a common accounting (virtual) currency in eleven of the member states. In 2002, it was turned into a fully-fledged conventible currency, when euro notes and coins were issued, while the phaseout of national currencies in the eurozone (consisting by then of 12 member states) was initiated. The eurozone (constituted by the EU member states which have adopted the euro) has since grown to 20 countries.[181][182]

The 20 EU member states known collectively as the eurozone have fully implemented the currency union by superseding their national currencies with the euro. The currency union represents 345 million EU citizens.[183] The euro is the second largest reserve currency as well as the second most traded currency in the world after the United States dollar.[184][185][186]

The euro, and the monetary policies of those who have adopted it in agreement with the EU, are under the control of the ECB.[187] The ECB is the central bank for the eurozone, and thus controls monetary policy in that area with an agenda to maintain price stability. It is at the centre of the Eurosystem, which comprehends all the Eurozone national central banks.[188] The ECB is also the central institution of the Banking Union established within the eurozone, as the hub of European Banking Supervision. There is also a Single Resolution Mechanism in case of a bank default.

As a political entity, the European Union is represented in the World Trade Organization (WTO). Two of the original core objectives of the European Economic Community were the development of a common market, subsequently becoming a single market, and a customs union between its member states.

The single market involves the free circulation of goods, capital, people, and services within the EU,[183] The free movement of services and of establishment allows self-employed persons to move between member states to provide services on a temporary or permanent basis. While services account for 60 per cent to 70 per cent of GDP, legislation in the area is not as developed as in other areas. This lacuna has been addressed by the Services in the Internal Market Directive 2006 which aims to liberalise the cross border provision of services.[189] According to the treaty the provision of services is a residual freedom that only applies if no other freedom is being exercised.

The customs union involves the application of a common external tariff on all goods entering the market. Once goods have been admitted into the market they cannot be subjected to customs duties, discriminatory taxes or import quotas, as they travel internally. The non-EU member states of Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Switzerland participate in the single market but not in the customs union.[145] Half the trade in the EU is covered by legislation harmonised by the EU.[190]

The European Union Association Agreement does something similar for a much larger range of countries, partly as a so-called soft approach ('a carrot instead of a stick') to influence the politics in those countries. The European Union represents all its members at the World Trade Organization (WTO), and acts on behalf of member states in any disputes. When the EU negotiates trade related agreement outside the WTO framework, the subsequent agreement must be approved by each individual EU member state government.[191]

The European Union has concluded free trade agreements (FTAs)[192] and other agreements with a trade component with many countries worldwide and is negotiating with many others.[193] The European Union's services trade surplus rose from $16 billion in 2000 to more than $250 billion in 2018.[194] In 2020, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, China became the EU's largest trading partner, displacing the United States.[195] The European Union is the largest exporter in the world[196] and in 2008 was the largest importer of goods and services.[197][198] Internal trade between the member states is aided by the removal of barriers to trade such as tariffs and border controls. In the eurozone, trade is helped by not having any currency differences to deal with amongst most members.[191] Externally, the EU's free-trade agreement with Japan is perhaps its most notable one. The EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement was officially signed on July 17, 2018, becoming the world's largest bilateral free trade deal when it went into effect on February 1, 2019, creating an open trade zone covering nearly one-third of global GDP.[199][200]

The EU operates a competition policy intended to ensure undistorted competition within the single market.[m] In 2001 the commission for the first time prevented a merger between two companies based in the United States (General Electric and Honeywell) which had already been approved by their national authority.[201] Another high-profile case, against Microsoft, resulted in the commission fining Microsoft over €777 million following nine years of legal action.[202]

Total energy supply (2019)[203]

The total energy supply of the EU was 59 billion GJ in 2019, about 10.2 per cent of the world total. Approximately three fifths of the energy available in the EU came from imports (mostly of fossil fuels). Renewable energy contributed 18.1 per cent of the EU's total energy supply in 2019, and 11.1 per cent of the final energy consumption.[204]

The EU has had legislative power in the area of energy policy for most of its existence; this has its roots in the original European Coal and Steel Community. The introduction of a mandatory and comprehensive European energy policy was approved at the meeting of the European Council in October 2005, and the first draft policy was published in January 2007.[205]

The EU has five key points in its energy policy: increase competition in the internal market, encourage investment and boost interconnections between electricity grids; diversify energy resources with better systems to respond to a crisis; establish a new treaty framework for energy co-operation with Russia while improving relations with energy-rich states in Central Asia[206] and North Africa; use existing energy supplies more efficiently while increasing renewable energy commercialisation; and finally increase funding for new energy technologies.[205]

In 2007, EU countries as a whole imported 82 per cent of their oil, 57 per cent of their natural gas[207] and 97.48 per cent of their uranium[208] demands. The three largest suppliers of natural gas to the European Union are Russia, Norway and Algeria, that amounted for about three quarters of the imports in 2019.[209] There is a strong dependence on Russian energy that the EU has been attempting to reduce.[210] However, in May 2022, it was reported that the European Union is preparing another sanction against Russia over its invasion of Ukraine. It is expected to target Russian oil, Russian and Belarusian banks, as well as individuals and companies. According to an article by Reuters, two diplomats stated that the European Union may impose a ban on imports of Russian oil by the end of 2022.[211] In May 2022, the European Commission published the 'RePowerEU' initiative, a €300 billion plan outlining the path towards the end of EU dependence on Russian fossil fuels by 2030 and the acceleration on the clean energy transition.[212]

The European Union manages cross-border road, railway, airport and water infrastructure through the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T), created in 1990,[213] and the Trans-European Combined Transport network. TEN-T comprises two network layers: the Core Network, which is to be completed by 2030; and the Comprehensive Network, which is to be completed by 2050. The network is currently made up of 9 core corridors: the Baltic–Adriatic Corridor, the North Sea–Baltic Corridor, the Mediterranean Corridor, the Orient/East–Med Corridor, the Scandinavian–Mediterranean Corridor, the Rhine–Alpine Corridor, the Atlantic Corridor, the North Sea–Mediterranean Corridor, and the Rhine–Danube Corridor. Road transportation was organised under the TEN-T by the Trans-European road network. Bundesautobahn 7 is the longest national motorway in the EU at 963 km (598 mi).

Maritime transportation is organised under the TEN-T by the Trans-European Inland Waterway network, and the Trans-European Seaport network. European seaports are categorized as international, community, or regional. The Port of Rotterdam is the busiest in the EU, and the world's largest seaport outside of East Asia, located in and near the city of Rotterdam, in the province of South Holland in the Netherlands.[214][215] The European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA), founded in 2002 in Lisbon, Portugal, is charged with reducing the risk of maritime accidents, marine pollution from ships and the loss of human lives at sea by helping to enforce the pertinent EU legislation.

Air transportation is organised under the TEN-T by the Trans-European Airport network. European airports are categorized as international, community, or regional. The Charles de Gaulle Airport is the busiest in the EU, located in and near the city of Paris, in France.[216] The European Common Aviation Area (ECAA) is a single market in aviation. ECAA agreements were signed on 5 May 2006 in Salzburg, Austria between the EU and some third countries. The ECAA liberalises the air transport industry by allowing any company from any ECAA member state to fly between any ECAA member states airports, thereby allowing a "foreign" airline to provide domestic flights. The Single European Sky (SES) is an initiative that seeks to reform the European air traffic management system through a series of actions carried out in four different levels (institutional, operational, technological and control and supervision) with the aim of satisfying the needs of the European airspace in terms of capacity, safety, efficiency and environmental impact. Civil aviation safety is under the responsibility of the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). It carries out certification, regulation and standardisation and also performs investigation and monitoring. The idea of a European-level aviation safety authority goes back to 1996, but the agency was only legally established in 2002, and began operating in 2003.

Rail transportation is organised under the TEN-T by the Trans-European Rail network, made up of the high-speed rail network and the conventional rail network. The Gare du Nord railway station is the busiest in the EU, located in and near the city of Paris, in France.[217][218] Rail transport in Europe is being synchronised with the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) with the goal of greatly enhancing safety, increase efficiency of train transports and enhance cross-border interoperability. This is done by replacing former national signalling equipment and operational procedures with a single new Europe-wide standard for train control and command systems. This system is conducted by the European Union Agency for Railways (ERA).

Mobile communication roaming charges are abolished throughout the EU, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway.

The European Union Agency for the Space Programme (EUSPA), headquartered in Prague, Czech Republic, was established in 2021 to manage the European Union Space Programme in order to implement the pre-existing European Space Policy, established on 22 May 2007 between the EU and the European Space Agency (ESA), known collectively as the European Space Council. This was the first common political framework for space activities established by the EU. Each member state has pursued to some extent their own national space policy, though often co-ordinating through the ESA. Günter Verheugen, the European Commissioner for Enterprise and Industry, has stated that even though the EU is "a world leader in the technology, it is being put on the defensive by the United States and Russia and that it only has about a 10-year technological advantage on China and India, which are racing to catch up."

Galileo is a global navigation satellite system (GNSS) that went live in 2016, created by the EU through the ESA, operated by the EUSPA, with two ground operations centres in Fucino, Italy, and Oberpfaffenhofen, Germany. The €10 billion project is named after the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei. One of the aims of Galileo is to provide an independent high-precision positioning system so European political and military authorities do not have to rely on the US GPS, or the Russian GLONASS systems, which could be disabled or degraded by their operators at any time. The European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service (EGNOS) is a satellite-based augmentation system (SBAS) developed by the ESA and EUROCONTROL. Currently, it supplements the GPS by reporting on the reliability and accuracy of their positioning data and sending out corrections. The system will supplement Galileo in a future version. The Copernicus Programme is the EU's Earth observation programme coordinated and managed by EUSPA in partnership with ESA. It aims at achieving a global, continuous, autonomous, high quality, wide range Earth observation capacity, providing accurate, timely and easily accessible information to, among other things, improve the management of the environment, understand and mitigate the effects of climate change, and ensure civil security.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is the agricultural policy of the European Union. It implements a system of agricultural subsidies and other programmes. It was introduced in 1962 and has since then undergone several changes to reduce the EEC budget cost (from 73% in 1985 to 37% in 2017) and consider rural development in its aims. It has, however, been criticised on the grounds of its cost and its environmental and humanitarian effects.

Likewise, the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) is the fisheries policy of the European Union. It sets quotas for which member states are allowed to catch each type of fish, as well as encouraging the fishing industry by various market interventions and fishing subsidies. It was introduced in 2009 with the Treaty of Lisbon, which formally enshrined fisheries conservation policy as one of the handful of "exclusive competences" reserved for the European Union.

The five European Structural and Investment Funds are supporting the development of the EU regions, primarily the underdeveloped ones, located mostly in the states of central and southern Europe.[220][221] Another fund (the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance) provides support for candidate members to transform their country to conform to the EU's standard. Demographic transition to a society of ageing population, low fertility-rates and depopulation of non-metropolitan regions is tackled within this policies.

The free movement of persons means that EU citizens can move freely between member states to live, work, study or retire in another country. This required the lowering of administrative formalities and recognition of professional qualifications of other states.[222] The EU seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 6.7 per cent in September 2018.[223] The euro area unemployment rate was 8.1 per cent.[223] Among the member states, the lowest unemployment rates were recorded in the Czech Republic (2.3 per cent), Germany and Poland (both 3.4 per cent), and the highest in Spain (11.27 per cent in 2024) and Greece (19.0 in July 2018).

The European Union has long sought to mitigate the effects of free markets by protecting workers' rights and preventing social and environmental dumping.[citation needed] To this end it has adopted laws establishing minimum employment and environmental standards. These included the Working Time Directive and the Environmental Impact Assessment Directive. The European Directive about Minimum Wage, which looks to lift minimum wages and strengthen collective bargaining was approved by the European Parliament in September 2022.[224]

The EU has also sought to coordinate the social security and health systems of member states to facilitate individuals exercising free movement rights and to ensure they maintain their ability to access social security and health services in other member states. Since 2019 there has been a European commissioner for equality and the European Institute for Gender Equality has existed since 2007. A Directive on countering gender-based violence has been proposed.[225][226] In September 2022, a European Care strategy was approved in order to provide "quality, affordable and accessible care services".[227] The European Social Charter is the main body that recognises the social rights of European citizens.

In 2020, the first ever European Union Strategy on LGBTIQ equality was approved under Helena Dalli mandate.[228] In December 2021, the commission announced the intention of codifying a union-wide law against LGBT hate crimes.[229]

Since the creation of the European Union in 1993, it has developed its competencies in the area of justice and home affairs; initially at an intergovernmental level and later by supranationalism. Accordingly, the union has legislated in areas such as extradition,[230] family law,[231] asylum law,[232] and criminal justice.[233]

The EU has also established agencies to co-ordinate police, prosecution and civil litigations across the member states: Europol for police co-operation, CEPOL for training of police forces[234] and the Eurojust for co-operation between prosecutors and courts.[235] It also operates the EUCARIS database of vehicles and drivers, the Eurodac, the European Criminal Records Information System, the European Cybercrime Centre, FADO, PRADO and others.

Prohibitions against discrimination have a long standing in the treaties. In more recent years, these have been supplemented by powers to legislate against discrimination based on race, religion, disability, age, and sexual orientation.[n] The treaties declare that the European Union itself is "founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities ... in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail."[236] By virtue of these powers, the EU has enacted legislation on sexism in the work-place, age discrimination, and racial discrimination.[o]

In 2009, the Lisbon Treaty gave legal effect to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. The charter is a codified catalogue of fundamental rights against which the EU's legal acts can be judged. It consolidates many rights which were previously recognised by the Court of Justice and derived from the "constitutional traditions common to the member states".[237] The Court of Justice has long recognised fundamental rights and has, on occasion, invalidated EU legislation based on its failure to adhere to those fundamental rights.[238]