Либертарианство (от французского libertaire , само от латинского libertas , букв. « свобода») — политическая философия , которая делает сильный акцент на ценности свободы. [1] [2] [3] [4] Либертарианцы выступают за расширение индивидуальной автономии и политической свободы , подчеркивая принципы равенства перед законом и защиту гражданских прав , включая право на свободу объединений , свободу слова , свободу мысли и свободу выбора . [4] [5] Либертарианцы часто выступают против власти , государственной власти, войны , милитаризма и национализма , но некоторые либертарианцы расходятся во мнениях относительно масштабов своего противостояния существующим экономическим и политическим системам . Различные школы либертарианской мысли предлагают ряд взглядов относительно законных функций государственной и частной власти . Для различения различных форм либертарианства использовались различные классификации. [6] [7] Ученые определили различные либертарианские взгляды на природу собственности и капитала , обычно описывая их по осям лево-право или социалист - капиталист . [8] Различные школы либертарианской мысли также были сформированы либеральными идеями. [9]

В середине 19 века [10] либертарианство возникло как форма левой политики, такой как антиавторитарные и антигосударственные социалисты, такие как анархисты , [11] особенно социальные анархисты , [12] но в более общем плане либертарианские коммунисты / марксисты и либертарианские социалисты . [13] [14] Эти либертарианцы стремились отменить капитализм и частную собственность на средства производства или же ограничить свою сферу деятельности или последствия нормами узуфрукта в пользу общей или кооперативной собственности и управления , рассматривая частную собственность на средства производства как препятствие к свободе и независимости. [19] Хотя все либертарианцы поддерживают определенный уровень индивидуальных прав , левые либертарианцы отличаются тем, что поддерживают эгалитарное перераспределение природных ресурсов. [20] Лево-либертарианские [26] идеологии включают анархистские школы мысли , наряду со многими другими антипатерналистскими и новыми левыми школами мысли, сосредоточенными вокруг экономического эгалитаризма , а также геолибертарианства , зеленой политики , рыночно-ориентированного левого либертарианства и школы Штайнера-Валлентайна . [30] После распада Советского Союза либертарианский социализм стал более популярным и влиятельным как часть антивоенных , антикапиталистических и анти- и альтерглобалистских движений. [31] [32]

В середине 20-го века американские правые либертарианцы [35], сторонники анархо-капитализма и минархизма, кооптировали [13] термин «либертарианец» для защиты капитализма невмешательства и сильных прав частной собственности , например, на землю, инфраструктуру и природные ресурсы. [36] Последнее является доминирующей формой либертарианства в Соединенных Штатах . [34] Это либертарианство, возрождение классического либерализма в Соединенных Штатах , [37] произошло из-за того, что другие американские либералы отказались от классического либерализма и приняли прогрессивизм и экономический интервенционизм в начале 20-го века после Великой депрессии и с Новым курсом . [38] С 1970-х годов эта классическая либеральная форма либертарианства распространилась за пределы Соединенных Штатов, [39] и праволибертарианские партии были созданы в Великобритании , [40] Израиле , [41] [42] [43] [ 44] Южной Африке [45] Аргентине и многих других странах. [46] Минархисты выступают за государства-сторожа , которые сохраняют только те функции правительства, которые необходимы для защиты естественных прав, понимаемых в терминах самопринадлежности или автономии, [47] в то время как анархо-капиталисты выступают за замену всех государственных институтов частными учреждениями. [48] Некоторые правые варианты либертарианства, такие как анархо-капитализм, были названы некоторыми учеными крайне правыми или радикально правыми . [49] [50] [51] [52] В 2022 году студент-активист и самопровозглашенный либертарианец-социалист Габриэль Борич стал главой государства Чили после победы на президентских выборах 2021 года в Чили с коалицией Apruebo Dignidad . [53] [54] [55] В 2023 году аргентинский экономист Хавьер Милей стал первым открыто правым либертарианским главой государства, [56] после победы на всеобщих выборах того года с коалицией La Libertad Avanza . [57]

Первое зафиксированное использование термина «либертарианец» относится к 1789 году, когда Уильям Белшем писал о либертарианстве в контексте метафизики. [58] Уже в 1796 году термин «либертарианец» стал означать сторонника или защитника свободы, особенно в политической и социальной сферах, когда 12 февраля London Packet напечатал следующее: «Недавно из тюрьмы в Бристоле вышли 450 французских либертарианцев». [59] Он снова был использован в политическом смысле в 1802 году в короткой статье, критикующей стихотворение «автора Гебира», и с тех пор используется в этом значении. [60] [61] [62]

Использование термина «либертарианец» для описания нового набора политических позиций восходит к французскому родственному слову «libertaire» , которое было введено в обращение в письме французского либертарианца-коммуниста Жозефа Дежака к мютюэлисту Пьеру-Жозефу Прудону в 1857 году. [63] Дежак также использовал этот термин для своего анархистского издания « Le Libertaire, Journal du mouvement social» ( Либертарианец: Журнал социального движения ), которое печаталось с 9 июня 1858 года по 4 февраля 1861 года в Нью-Йорке. [64] Себастьен Фор , другой французский либертарианец-коммунист, начал издавать новый «Le Libertaire» в середине 1890-х годов, в то время как Третья республика во Франции приняла так называемые злодейские законы ( lois scélérates ), запрещавшие анархистские публикации во Франции. С тех пор термин «либертарианство» часто использовался для обозначения анархизма и либертарианского социализма . [65] [66] [67]

В Соединенных Штатах термин «либертарианство» был популяризирован анархистом -индивидуалистом Бенджамином Такером в конце 1870-х и начале 1880-х годов. [68] Термин «либертарианство» как синоним либерализма был популяризирован в мае 1955 года писателем Дином Расселом, коллегой Леонарда Рида и классическим либералом . Рассел обосновал выбор термина следующим образом:

Многие из нас называют себя «либералами». И это правда, что слово «либерал» когда-то описывало людей, которые уважали личность и боялись использования массового принуждения. Но левые теперь извратили этот некогда гордый термин, чтобы идентифицировать себя и свою программу большего государственного владения собственностью и большего контроля над людьми. В результате, те из нас, кто верит в свободу, должны объяснить, что когда мы называем себя либералами, мы имеем в виду либералов в неиспорченном классическом смысле. В лучшем случае это неловко и подвержено непониманию. Вот предложение: пусть те из нас, кто любит свободу, зарегистрируют и зарезервируют для собственного использования хорошее и почетное слово «либертарианец». [69] [70] [71]

Впоследствии все большее число американцев с классическими либеральными убеждениями стали называть себя либертарианцами . Одним из людей, ответственных за популяризацию термина «либертарианец» в этом смысле, был Мюррей Ротбард , который начал публиковать либертарианские работы в 1960-х годах. [72] Ротбард открыто описал это современное использование слов как «захват» у своих врагов, написав, что «впервые на моей памяти мы, «наша сторона», захватили важное слово у врага. «Либертарианцы» долгое время были просто вежливым словом для левых анархистов, то есть для анархистов, выступающих против частной собственности, как коммунистического, так и синдикалистского толка. Но теперь мы переняли его». [13]

В 1970-х годах Роберт Нозик был ответственен за популяризацию этого использования термина в академических и философских кругах за пределами Соединенных Штатов, [34] [73] [74] особенно с публикацией книги «Анархия, государство и утопия» (1974), ответом на работу социал-либерала Джона Ролза « Теория справедливости» (1971). [75] В книге Нозик предложил минимальное государство на том основании, что это неизбежное явление, которое может возникнуть без нарушения прав личности . [76]

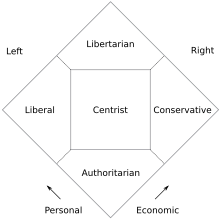

Согласно общепринятым в США значениям консерватора и либерала , либертарианство в США описывается как консервативное в экономических вопросах ( экономический либерализм и фискальный консерватизм ) и либеральное в вопросах личной свободы ( гражданское либертарианство и культурный либерализм ). [77] Его также часто ассоциируют с внешней политикой невмешательства . [78] [79]

Хотя либертарианство зародилось как форма левой политики , [29] [81] развитие в середине 20-го века современного либертарианства в Соединенных Штатах привело к тому, что либертарианство стало обычно ассоциироваться с правой политикой , а также многими рассматривалось как не левое и не правое, а как независимая просвободная и антиавторитарная философия. [82] Это также привело к тому, что несколько авторов и политологов стали использовать две или более категоризации [6] [7] [20] для различения либертарианских взглядов на природу собственности и капитала, обычно по линиям лево-право или социалист-капиталист. [8] Правые либертарианцы отвергают этот ярлык из-за его связи с консерватизмом и правой политикой, называя себя просто либертарианцами , в то время как сторонники антикапитализма свободного рынка в Соединенных Штатах сознательно называют себя левыми либертарианцами и считают себя частью широкого левого либертарианства. [29] [81]

Хотя термин «либертарианец» в значительной степени был синонимом анархизма как части левого движения, [14] [83] продолжая сегодня как часть либертарианского левого движения в оппозиции к умеренному левому движению, такому как социальная демократия или авторитарный и этатистский социализм, его значение изменилось за последние полвека, с более широким принятием идеологически разрозненными группами, [14] включая некоторые, рассматриваемые как правые старыми пользователями термина. [22] [33] Как термин, либертарианец может включать как новых левых марксистов (которые не ассоциируются с авангардной партией ), так и крайних либералов (в первую очередь озабоченных гражданскими свободами ) или гражданских либертарианцев . Кроме того, некоторые либертарианцы используют термин « либертарианский социалист» , чтобы избежать негативных коннотаций анархизма и подчеркнуть его связь с социализмом. [14] [84]

Возрождение идеологий свободного рынка в середине-конце 20-го века сопровождалось разногласиями по поводу того, как называть движение. В то время как многие сторонники свободного рынка предпочитают термин «либертарианство» , многие консервативные либертарианцы отвергают связь термина с «новыми левыми» 1960-х годов и его коннотациями либертарного гедонизма. [85] Движение разделено по поводу использования консерватизма в качестве альтернативы. [86] Те, кто стремится как к экономической, так и к социальной свободе, известны как либералы , но этот термин развил ассоциации, противоположные ограниченному правительству , низкому налогообложению, минимальному государству, пропагандируемым движением. [87] Варианты названий движения за возрождение свободного рынка включают классический либерализм , экономический либерализм , либерализм свободного рынка и неолиберализм . [85] Термин «либертарианец» или «экономический либертарианец» наиболее распространен в разговорной речи для описания члена движения, причем последний термин основан как на главенстве экономики в идеологии, так и на ее отличии от либертарианцев Новых левых. [86]

В то время как и историческое, и современное либертарианство разделяют общую антипатию к власти правительственной власти, последнее исключает власть, осуществляемую посредством капитализма свободного рынка . Исторически либертарианцы, включая Герберта Спенсера и Макса Штирнера, поддерживали защиту свободы личности от власти правительства и частной собственности. [88] Напротив, осуждая посягательство правительства на личные свободы, современные американские либертарианцы поддерживают свободы на основе их согласия с правами частной собственности. [89] Отмена общественных удобств является распространенной темой в современных американских либертарианских трудах. [90]

По словам современного американского либертарианца Уолтера Блока , левые и правые либертарианцы согласны с некоторыми либертарианскими предпосылками, но «они различаются в плане логических следствий этих основополагающих аксиом». [82] Хотя некоторые современные американские либертарианцы отвергают политический спектр , особенно лево-правый политический спектр , [91] [92] [93] [94] [95] несколько направлений либертарианства в Соединенных Штатах и правого либертарианства были описаны как правые, [96] новые правые [97] [98] или радикально правые [99] [100] и реакционные . [101] В то время как некоторые американские либертарианцы, такие как Уолтер Блок , [82] Гарри Браун , [93] Тибор Махан , [95] Джастин Раймондо , [94] Леонард Рид [92] и Мюррей Ротбард [91] отрицают какую-либо связь с левыми или правыми, другие американские либертарианцы, такие как Кевин Карсон , [29] Карл Гесс , [102] и Родерик Т. Лонг [103], писали о левой оппозиции либертарианства авторитарному правлению и утверждали, что либертарианство по сути своей является левой позицией. Сам Ротбард ранее высказывал ту же точку зрения. [104]

Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии определяет либертарианство как моральную точку зрения, согласно которой агенты изначально полностью владеют собой и имеют определенные моральные полномочия для приобретения прав собственности на внешние вещи. [20] Историк-либертарианец Джордж Вудкок определяет либертарианство как философию, которая фундаментально сомневается во власти и выступает за преобразование общества путем реформ или революции. [105] Философ-либертарианец Родерик Т. Лонг определяет либертарианство как «любую политическую позицию, которая выступает за радикальное перераспределение власти от принудительного государства к добровольным объединениям свободных людей», независимо от того, принимает ли «добровольное объединение» форму свободного рынка или коммунальных кооперативов. [106] Согласно Американской либертарианской партии , либертарианство — это защита правительства, которое финансируется добровольно и ограничивается защитой людей от принуждения и насилия. [107]

Согласно Интернет-энциклопедии философии (IEP), «То, что значит быть «либертарианцем» в политическом смысле, является спорным вопросом, особенно среди самих либертарианцев». [108] Тем не менее, все либертарианцы начинают с концепции личной автономии, из которой они выступают в пользу гражданских свобод и сокращения или устранения государства. [4] Люди, описываемые как левые либертарианцы или правые либертарианцы, как правило, называют себя просто либертарианцами и ссылаются на свою философию как на либертарианство. В результате некоторые политологи и писатели классифицируют формы либертарианства на две или более группы [6] [7], чтобы различать либертарианские взгляды на природу собственности и капитала . [8] [18] В Соединенных Штатах сторонники антикапитализма свободного рынка сознательно называют себя левыми либертарианцами и видят себя частью широкого левого либертарианства. [29] [81]

Либертарианство — это «теория, отстаивающая... права [личности]... превыше всего» и стремящаяся «уменьшить» власть государства или государств, особенно тех, в которых живет или с которыми тесно связан либертарианец, чтобы «защитить» и сохранить индивидуализм. [109]

Либертарианцы утверждают, что некоторые формы порядка в обществе возникают спонтанно из действий множества различных людей, действующих независимо друг от друга, без какого-либо центрального планирования . [4] Предлагаемые примеры систем, которые развивались посредством спонтанного порядка или самоорганизации, включают эволюцию жизни на Земле , языка , кристаллической структуры , Интернета , Википедии , рабочих советов , Горизонталидада и свободной рыночной экономики . [110] [111]

Леволибертарианство [22] [23] [25] охватывает те либертарианские убеждения, которые утверждают, что природные ресурсы Земли принадлежат всем на равноправной основе, как бесхозные, так и находящиеся в коллективной собственности. [21] [24] [27] [28] [34] Современные леволибертарианцы, такие как Хиллель Штайнер , Питер Валлентайн , Филипп Ван Парийс , Майкл Оцука и Дэвид Эллерман, считают, что присвоение земли должно оставлять « достаточно и такого же качества » для других или облагаться налогом обществом для компенсации исключающего эффекта частной собственности. [21] [28] Социалистические либертарианцы [15] [16] [17] [18], такие как социальные и индивидуалистические анархисты , либертарианские марксисты , коммунисты советов , люксембургисты и де леонисты, продвигают узуфрукт и социалистические экономические теории, включая коммунизм , коллективизм , синдикализм и мутуализм . [27] [29] Они критикуют государство за то, что оно защищает частную собственность, и считают, что капитализм влечет за собой наемное рабство и другую форму принуждения и господства, связанную с государством. [15] [16] [17]

Существует ряд различных леволибертарианских позиций по вопросу государства, которые могут варьироваться от отстаивания полной отмены государства до отстаивания более децентрализованного и ограниченного правительства с общественной собственностью на экономику. [112] По словам Шелдона Ричмана из Независимого института , другие леволибертарианцы «предпочитают, чтобы корпоративные привилегии были отменены до введения нормативных ограничений на то, как эти привилегии могут осуществляться». [113]

Правое либертарианство [22] [25] [33] [34] развилось в Соединенных Штатах в середине 20-го века из работ таких европейских писателей, как Джон Локк , Фридрих Хайек и Людвиг фон Мизес , и является самой популярной концепцией либертарианства в Соединенных Штатах сегодня. [34] [73] Обычно его называют продолжением или радикализацией классического либерализма , [114] [115] наиболее важным из этих ранних праволибертарианских философов был Роберт Нозик . [34] [73] [76] Разделяя защиту левых либертарианцев социальной свободы, правые либертарианцы ценят социальные институты , которые обеспечивают условия капитализма, отвергая институты, которые функционируют в противовес им, на том основании, что такие вмешательства представляют собой ненужное принуждение людей и отмену их экономической свободы. [116] Анархо-капиталисты [25] [33] стремятся к устранению государства в пользу частных служб безопасности, в то время как минархисты защищают государства-ночные сторожа , которые сохраняют только те функции правительства, которые необходимы для защиты естественных прав, понимаемых в терминах самопринадлежности или автономии. [47]

Либертарианский патернализм [117] — это позиция, отстаиваемая в международном бестселлере «Подталкивание» двумя американскими учеными, а именно экономистом Ричардом Талером и юристом Кассом Санстейном . [118] В книге « Думай медленно… решай быстро » Дэниел Канеман приводит краткое резюме: «Талер и Санстейн отстаивают позицию либертарианский патернализм, в которой государство и другие институты имеют право подталкивать людей к принятию решений, которые служат их собственным долгосрочным интересам. Назначение присоединения к пенсионному плану в качестве опции по умолчанию является примером подталкивания. Трудно утверждать, что свобода кого-либо уменьшается из-за автоматического зачисления в план, когда им просто нужно поставить галочку, чтобы отказаться». [119] «Подталкивание» считается важным произведением литературы по поведенческой экономике . [119]

Неолибертарианство сочетает в себе «моральную приверженность либертарианца негативной свободе с процедурой, которая выбирает принципы ограничения свободы на основе единогласного соглашения, в котором частные интересы каждого получают справедливое слушание». [120] Неолибертарианство берет свое начало, по крайней мере, в 1980 году, когда оно было впервые описано американским философом Джеймсом Стербой из Университета Нотр-Дам . Стерба заметил, что либертарианство выступает за правительство, которое делает не больше, чем защиту от силы, мошенничества, воровства, принуждения к исполнению контрактов и других негативных свобод , в отличие от позитивных свобод Исайи Берлина . [121] Стерба противопоставил это более старому либертарианскому идеалу государства ночного сторожа, или минархизму. Стерна считал, что «очевидно невозможно гарантировать полную свободу каждому человеку в обществе, как определено этим идеалом: в конце концов, фактические желания людей, а также их мыслимые желания могут вступить в серьезный конфликт. [...] [И]также невозможно, чтобы каждый человек в обществе был полностью свободен от вмешательства других лиц». [122] В 2013 году Стерна написал, что «я покажу, что моральная приверженность идеалу «негативной» свободы, которая не приводит к государству ночного сторожа, а вместо этого требует достаточного правительства, чтобы предоставить каждому человеку в обществе относительно высокий минимум свободы, который выберут люди, использующие процедуру принятия решений Ролза . Политическую программу, фактически оправданную идеалом негативной свободы, я буду называть неолибертарианством ». [123]

Либертарианский популизм сочетает в себе либертарианскую и популистскую политику. По словам Джесси Уокера , пишущего в либертарианском журнале Reason , либертарианские популисты выступают против «большого правительства», а также против «других крупных централизованных институтов» и выступают за то, чтобы «рубить топором чащу корпоративных субсидий, льгот и спасений, расчищая нам путь к экономике, в которой предприятия, которые не могут зарабатывать деньги, обслуживая клиентов, не имеют возможности вместо этого выжимать прибыль из налогоплательщиков». [124]

В Соединенных Штатах либертарианство — это типология, используемая для описания политической позиции, которая выступает за небольшое правительство и является культурно либеральной и фискально консервативной в двухмерном политическом спектре, таком как вдохновленная либертарианством диаграмма Нолана , где другие основные типологии — консервативная , либеральная и популистская . [77] [125] [126] [127] Либертарианцы поддерживают легализацию преступлений без жертв, таких как употребление марихуаны, одновременно выступая против высоких уровней налогообложения и государственных расходов на здравоохранение, социальное обеспечение и образование. [77] Либертарианцы также поддерживают внешнюю политику невмешательства . [128] [129] Либертарианство было принято в Соединенных Штатах, где либеральное стало ассоциироваться с версией, которая поддерживает обширные государственные расходы на социальную политику. [71] Либертарианство может также относиться к анархистской идеологии, которая развилась в 19 веке, и к либеральной версии, которая развилась в Соединенных Штатах и которая открыто выступает за капитализм . [21] [22] [25]

Согласно опросам, примерно один из четырех американцев идентифицирует себя как либертарианец . [130] [131] [132] [133] Хотя эта группа обычно не идеологически движима, термин «либертарианец» обычно используется для описания формы либертарианства, широко практикуемой в Соединенных Штатах, и является общим значением слова «либертарианство» в Соединенных Штатах. [34] Эту форму часто называют либерализмом в других местах, например, в Европе, где либерализм имеет другое общее значение, чем в Соединенных Штатах. [71] В некоторых академических кругах эту форму называют правым либертарианством как дополнение к левому либертарианству , при этом принятие капитализма или частной собственности на землю является отличительной чертой. [21] [22] [25]

Элементы либертарианства можно проследить до концепций высшего закона греков и израильтян , а также христианских теологов , которые отстаивали моральную ценность личности и разделение мира на две сферы, одна из которых является областью Бога и, таким образом, находится за пределами власти государств контролировать ее. [4] [134] Правый либертарианский экономист Мюррей Ротбард предположил, что китайский даосский философ Лао-цзы был первым либертарианцем, [135] сравнив идеи Лао-цзы о правительстве с теорией спонтанного порядка Фридриха Хайека . [136] Аналогичным образом Дэвид Боаз из Института Катона включает отрывки из Дао Дэ Цзин в свою книгу 1997 года «Либертарианский читатель» и отметил в статье для Encyclopaedia Britannica , что Лао-цзы выступал за то, чтобы правители «ничего не делали», потому что «без закона или принуждения люди жили бы в гармонии». [137] Либертарианство находилось под влиянием дебатов внутри схоластики относительно частной собственности и рабства . [4] Схоластические мыслители, включая Фому Аквинского , Франсиско де Виторию и Бартоломе де Лас Касаса , отстаивали концепцию «самовладения» как основу системы, поддерживающей индивидуальные права. [4]

Ранние христианские секты, такие как вальденсы, демонстрировали либертарианские взгляды. [138] [139] В Англии XVII века либертарианские идеи начали приобретать современную форму в трудах левеллеров и Джона Локка . В середине того столетия противников королевской власти стали называть вигами , а иногда просто оппозицией или страной, в отличие от придворных писателей. [140]

В XVIII веке и в эпоху Просвещения либеральные идеи процветали в Европе и Северной Америке. [141] [142] Либертарианцы разных школ находились под влиянием либеральных идей. [9] По мнению философа Родерика Т. Лонга, либертарианцы «имеют общее — или, по крайней мере, частично совпадающее — интеллектуальное происхождение. [Либертарианцы] [...] заявляют, что английские левеллеры семнадцатого века и французские энциклопедисты восемнадцатого века являются их идеологическими предшественниками; и [...] обычно разделяют восхищение Томасом Джефферсоном и Томасом Пейном ». [143]

Джон Локк оказал большое влияние как на либертарианство, так и на современный мир в своих трудах, опубликованных до и после Английской революции 1688 года , особенно в «Письме о веротерпимости» (1667), «Двух трактатах о правительстве» (1689) и «Эссе о человеческом понимании» (1690). В тексте 1689 года он заложил основу либеральной политической теории, а именно, что права людей существовали до правительства; что цель правительства — защищать личные и имущественные права; что люди могут распускать правительства, которые этого не делают; и что представительное правительство — лучшая форма защиты прав. [144]

Декларация независимости Соединенных Штатов была вдохновлена Локком в его заявлении: «[Д]ля обеспечения этих прав среди людей учреждаются правительства, черпающие свою справедливую власть из согласия управляемых . Что всякий раз, когда какая-либо форма правления становится разрушительной для этих целей, народ имеет право изменить или упразднить ее». [145] По словам американского историка Бернарда Бейлина , во время и после Американской революции «основные темы либертарианства восемнадцатого века были воплощены в жизнь» в конституциях , биллях о правах и ограничениях законодательной и исполнительной власти, включая ограничения на начало войн. [4]

По словам Мюррея Ротбарда , либертарианское кредо возникло из либеральных вызовов «абсолютному центральному государству и королю, правящему по божественному праву поверх старой, ограничительной сети феодальных земельных монополий и контроля и ограничений городских гильдий», а также меркантилизма бюрократического военного государства, связанного с привилегированными торговцами. Целью либералов была индивидуальная свобода в экономике, в личных свободах и гражданской свободе, разделение государства и религии и мир как альтернатива имперскому возвеличиванию. Он цитирует современников Локка, левеллеров, которые придерживались схожих взглядов. Также оказали влияние английские « Письма Катона» в начале 1700-х годов, которые охотно перепечатывали американские колонисты , которые уже были свободны от европейской аристократии и феодальных земельных монополий. [145]

В январе 1776 года, всего через два года после приезда в Америку из Англии, Томас Пейн опубликовал свой памфлет «Здравый смысл», призывающий к независимости колоний. [146] Пейн пропагандировал либеральные идеи ясным и лаконичным языком, который позволял широкой публике понимать дебаты среди политической элиты. [147] «Здравый смысл» был чрезвычайно популярен в распространении этих идей, [148] продаваясь сотнями тысяч экземпляров. [149] Позже Пейн напишет « Права человека» и «Век разума» и примет участие во Французской революции . [146] Теория собственности Пейна демонстрировала «либертарианскую озабоченность» перераспределением ресурсов. [150]

В 1793 году Уильям Годвин написал либертарианский философский трактат под названием «Исследование политической справедливости и ее влияния на мораль и счастье» , в котором критиковал идеи прав человека и общества по контракту, основанные на неопределенных обещаниях. Он довел либерализм до его логического анархического завершения, отвергнув все политические институты, закон, правительство и аппарат принуждения, а также все политические протесты и восстания. Вместо институционализированной справедливости Годвин предложил, чтобы люди влияли друг на друга к моральному благу посредством неформального обоснованного убеждения, в том числе в ассоциациях, к которым они присоединялись, поскольку это способствовало бы счастью. [151]

Философ-анархист-коммунист Жозеф Дежак был первым человеком, назвавшим себя либертарианцем [ 10] в письме 1857 года. [152] В отличие от философа-анархиста-мутуалиста Пьера-Жозефа Прудона , он утверждал, что «не на продукт своего труда рабочий имеет право, а на удовлетворение своих потребностей, какова бы ни была их природа». [153] [154] По словам историка-анархиста Макса Неттлау , первое использование термина «либертарианский коммунизм» произошло в ноябре 1880 года, когда французский анархистский конгресс использовал его для более четкого обозначения своих доктрин. [155] Французский журналист-анархист Себастьен Фор начал издавать еженедельную газету Le Libertaire ( Либертарианец ) в 1895 году. [156]

Революционная волна 1917–1923 годов характеризовалась активным участием анархистов в России и Европе. Российские анархисты участвовали вместе с большевиками в революциях Февраля и Октября 1917 года. Однако большевики в Центральной России быстро начали сажать в тюрьмы или загонять в подполье анархистов-либертарианцев. Многие бежали на Украину. [157] После того, как анархистская махновщина помогла остановить Белое движение во время Гражданской войны в России , большевики выступили против махновцев и способствовали расколу между анархо-синдикалистами и коммунистами. [158]

С ростом фашизма в Европе между 1920-ми и 1930-ми годами анархисты начали бороться с фашистами в Италии [159] , во Франции во время беспорядков в феврале 1934 года [160] и в Испании, где бойкот выборов CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) привел к победе правых, а ее последующее участие в голосовании в 1936 году помогло вернуть народный фронт к власти. Это привело к попытке переворота правящего класса и гражданской войне в Испании (1936–1939). [161] Gruppo Comunista Anarchico di Firenze считала, что в начале двадцатого века термины либертарианский коммунизм и анархистский коммунизм стали синонимами в международном анархистском движении в результате их тесной связи в Испании ( анархизм в Испании ), причем либертарианский коммунизм стал преобладающим термином. [162]

Либертарианский социализм достиг пика популярности с Испанской революцией 1936 года , во время которой либертарианские социалисты возглавили «крупнейшую и самую успешную революцию против капитализма, когда-либо имевшую место в любой индустриальной экономике». [163] Во время революции средства производства были взяты под контроль рабочих , а рабочие кооперативы сформировали основу новой экономики. [164] По словам Гастона Леваля , CNT создала аграрную федерацию в Леванте, которая охватывала 78% наиболее пахотных земель Испании . Региональная федерация насчитывала 1 650 000 человек, 40% из которых жили в 900 аграрных коллективах региона, которые были самоорганизованы крестьянскими союзами. [165] Хотя промышленное и сельскохозяйственное производство было на самом высоком уровне в контролируемых анархистами районах Испанской Республики, а анархистские ополчения демонстрировали сильнейшую военную дисциплину, либералы и коммунисты в равной степени обвиняли « сектантских » либертарианских социалистов в поражении Республики в гражданской войне в Испании . Эти обвинения были оспорены современными либертарианскими социалистами, такими как Робин Ханель и Ноам Хомский, которые обвинили такие заявления в отсутствии существенных доказательств. [166]

Осенью 1931 года активисты анархистского профсоюза CNT опубликовали «Манифест 30-ти», и среди подписавших его были генеральный секретарь CNT (1922–1923) Жоан Пейро, Анхель Пестанья CNT (генеральный секретарь в 1929 году) и Хуан Лопес Санчес. Их называли треинтизмом , и они призывали к либертарианскому поссибилизму , который выступал за достижение либертарианских социалистических целей с участием внутри структур современной парламентской демократии . [167] В 1932 году они основали Синдикалистскую партию , которая участвовала во всеобщих выборах в Испании 1936 года и вошла в состав левой коалиции партий, известной как Народный фронт, получив двух конгрессменов (Пестанья и Бенито Пабон). В 1938 году генеральный секретарь CNT Орасио Прието предложил, чтобы Иберийская анархистская федерация преобразовалась в Либертарианскую социалистическую партию и чтобы она приняла участие в национальных выборах. [168]

Манифест либертарианского коммунизма был написан в 1953 году Жоржем Фонтени для Федерации коммунистов-либертарианцев Франции. Это один из ключевых текстов анархо-коммунистического течения, известного как платформизм . [169] В 1968 году во время международной анархистской конференции в Карраре , Италия, был основан Интернационал анархистских федераций для продвижения либертарианской солидарности. Он хотел сформировать «сильное и организованное рабочее движение, согласное с либертарианскими идеями». [170] [171] В Соединенных Штатах Либертарианская лига была основана в Нью-Йорке в 1954 году как леволибертарианская политическая организация, опирающаяся на Либертарианский книжный клуб . [172] [173] Среди ее членов были Сэм Долгофф , [174] Рассел Блэквелл , Дэйв Ван Ронк , Энрико Арригони [175] и Мюррей Букчин .

В Австралии Sydney Push была преимущественно левой интеллектуальной субкультурой в Сиднее с конца 1940-х до начала 1970-х годов, которая стала ассоциироваться с ярлыком Sydney libertarianism. Известными соратниками Push являются Джим Бейкер , Джон Флаус , Гарри Хутон , Маргарет Финк , Саша Солдатов, [176] Лекс Бэннинг , Ева Кокс , Ричард Эпплтон , Пэдди МакГиннесс , Дэвид Макинсон , Жермен Грир , Клайв Джеймс , Роберт Хьюз , Фрэнк Мурхаус и Лилиан Роксон . Среди ключевых интеллектуальных фигур в дебатах Push были философы Дэвид Дж. Айвисон, Джордж Молнар , Рулоф Смайлд, Дарси Уотерс и Джим Бейкер, как записано в мемуарах Бейкера Sydney Libertarians and the Push , опубликованных в либертарианском Broadsheet в 1975 году. [177] Понимание либертарианских ценностей и социальной теории можно получить из их публикаций, некоторые из которых доступны в Интернете. [178] [179]

В 1969 году французский платформист анархо-коммунист Даниэль Герен опубликовал эссе под названием «Либертарианский марксизм?», в котором он рассматривал дебаты между Карлом Марксом и Михаилом Бакуниным в Первом Интернационале . [180] Либертарианские марксистские течения часто черпают вдохновение из поздних работ Маркса и Энгельса, в частности, из « Grundrisse» и «Гражданской войны во Франции» . [181]

HL Mencken и Albert Jay Nock были первыми видными деятелями в Соединенных Штатах, которые назвали себя либертарианцами как синонимом либерала . Они считали, что Франклин Д. Рузвельт позаимствовал слово «либерал» для своей политики Нового курса , против которой они выступали, и использовали слово «либертарианец» для обозначения своей преданности классическому либерализму , индивидуализму и ограниченному правительству . [182]

По словам Дэвида Боаза , в 1943 году три женщины «опубликовали книги, которые, можно сказать, дали начало современному либертарианскому движению». [183] «Бог машины » Изабель Патерсон , «Открытие свободы » Роуз Уайлдер Лейн и «Источник» Айн Рэнд — каждая из них пропагандировала индивидуализм и капитализм. Никто из них не использовал термин «либертарианство» для описания своих убеждений, и Рэнд специально отвергала этот ярлык, критикуя зарождающееся американское либертарианское движение как «хиппи правых». [184] Рэнд обвинила либертарианцев в плагиате идей, связанных с ее собственной философией объективизма, и при этом яростно нападала на другие ее аспекты. [184]

В 1946 году Леонард Э. Рид основал Фонд экономического образования (FEE), американскую некоммерческую образовательную организацию, которая продвигает принципы невмешательства в экономику, частной собственности и ограниченного правительства. [185] По словам Гэри Норта , FEE является «дедушкой всех либертарианских организаций». [186]

Карл Гесс , спичрайтер Барри Голдуотера и основной автор платформ Республиканской партии 1960 и 1964 годов , разочаровался в традиционной политике после президентской кампании 1964 года , в которой Голдуотер проиграл Линдону Б. Джонсону . Он и его друг Мюррей Ротбард , экономист австрийской школы , основали журнал Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought , который издавался с 1965 по 1968 год совместно с Джорджем Решем и Леонардом П. Лиджио . В 1969 году они редактировали The Libertarian Forum , который Гесс покинул в 1971 году. [187]

The Vietnam War split the uneasy alliance between growing numbers of American libertarians and conservatives who believed in limiting liberty to uphold moral virtues. Libertarians opposed to the war joined the draft resistance and peace movements as well as organizations such as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). In 1969 and 1970, Hess joined with others, including Murray Rothbard, Robert LeFevre, Dana Rohrabacher, Samuel Edward Konkin III and former SDS leader Carl Oglesby to speak at two conferences which brought together activists from both the New Left and the Old Right in what was emerging as a nascent libertarian movement. Rothbard ultimately broke with the left, allying himself with the burgeoning paleoconservative movement.[188][189] He criticized the tendency of these libertarians to appeal to "'free spirits,' to people who don't want to push other people around, and who don't want to be pushed around themselves" in contrast to "the bulk of Americans" who "might well be tight-assed conformists, who want to stamp out drugs in their vicinity, kick out people with strange dress habits, etc." Rothbard emphasized that this was relevant as a matter of strategy as the failure to pitch the libertarian message to Middle America might result in the loss of "the tight-assed majority".[190][191] This left-libertarian tradition has been carried to the present day by Konkin's agorists,[192] contemporary mutualists such as Kevin Carson,[193] Roderick T. Long[194] and others such as Gary Chartier[195] Charles W. Johnson[196][197] Sheldon Richman,[198] Chris Matthew Sciabarra[199] and Brad Spangler.[200]

.jpg/440px-Ron_Paul_(6811133499).jpg)

In 1971, a small group led by David Nolan formed the Libertarian Party,[201] which has run a presidential candidate every election year since 1972. Other libertarian organizations, such as the Center for Libertarian Studies and the Cato Institute, were also formed in the 1970s.[202] Philosopher John Hospers, a one-time member of Rand's inner circle, proposed a non-initiation of force principle to unite both groups, but this statement later became a required "pledge" for candidates of the Libertarian Party and Hospers became its first presidential candidate in 1972.[203]

Modern libertarianism gained significant recognition in academia with the publication of Harvard University professor Robert Nozick's Anarchy, State, and Utopia in 1974, for which he received a National Book Award in 1975.[204] In response to John Rawls' A Theory of Justice, Nozick's book supported a minimal state (also called a nightwatchman state by Nozick) on the grounds that the ultraminimal state arises without violating individual rights[205] and the transition from an ultraminimal state to a minimal state is morally obligated to occur.

In the early 1970s, Rothbard wrote: "One gratifying aspect of our rise to some prominence is that, for the first time in my memory, we, 'our side,' had captured a crucial word from the enemy. 'Libertarians' had long been simply a polite word for left-wing anarchists, that is for anti-private property anarchists, either of the communist or syndicalist variety. But now we had taken it over".[206] The project of spreading libertarian ideals in the United States has been so successful that some Americans who do not identify as libertarian seem to hold libertarian views.[207] Since the resurgence of neoliberalism in the 1970s, this modern American libertarianism has spread beyond North America via think tanks and political parties.[208][209]

In a 1975 interview with Reason, California Governor Ronald Reagan appealed to libertarians when he stated to "believe the very heart and soul of conservatism is libertarianism".[210] Libertarian Republican Ron Paul supported Reagan's 1980 presidential campaign, being one of the first elected officials in the nation to support his campaign[211] and actively campaigned for Reagan in 1976 and 1980.[212] However, Paul quickly became disillusioned with the Reagan administration's policies after Reagan's election in 1980 and later recalled being the only Republican to vote against Reagan budget proposals in 1981.[213][214] In the 1980s, libertarians such as Paul and Rothbard[215][216] criticized President Reagan, Reaganomics and policies of the Reagan administration for, among other reasons, having turned the United States' big trade deficit into debt and the United States became a debtor nation for the first time since World War I under the Reagan administration.[217][218] Rothbard argued that the presidency of Reagan has been "a disaster for libertarianism in the United States"[219] and Paul described Reagan himself as "a dramatic failure".[212]

A surge of popular interest in libertarian socialism occurred in Western nations during the 1960s and 1970s.[220] Anarchism was influential in the counterculture of the 1960s[221][222][223] and anarchists actively participated in the protests of 1968 which included students and workers' revolts.[224] In 1968, the International of Anarchist Federations was founded in Carrara, Italy during an international anarchist conference held there in 1968 by the three existing European federations of France, the Italian and the Iberian Anarchist Federation as well as the Bulgarian Anarchist Federation in French exile.[171][225]

Around the turn of the 21st century, libertarian socialism grew in popularity and influence as part of the anti-war, anti-capitalist and anti-globalisation movements.[31] Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against the meetings of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Group of Eight and the World Economic Forum. Some anarchist factions at these protests engaged in rioting, property destruction and violent confrontations with police. These actions were precipitated by ad hoc, leaderless, anonymous cadres known as black blocs and other organizational tactics pioneered in this time include security culture, affinity groups and the use of decentralized technologies such as the Internet.[31] A significant event of this period was the confrontations at WTO conference in Seattle in 1999.[31] For English anarchist scholar Simon Critchley, "contemporary anarchism can be seen as a powerful critique of the pseudo-libertarianism of contemporary neo-liberalism. One might say that contemporary anarchism is about responsibility, whether sexual, ecological or socio-economic; it flows from an experience of conscience about the manifold ways in which the West ravages the rest; it is an ethical outrage at the yawning inequality, impoverishment and disenfranchisment that is so palpable locally and globally".[226] This might also have been motivated by "the collapse of 'really existing socialism' and the capitulation to neo-liberalism of Western social democracy".[227]

Since the end of the Cold War, there have been at least two major experiments in libertarian socialism: the Zapatista uprising in Mexico, during which the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) enabled the formation of a self-governing autonomous territory in the Mexican state of Chiapas;[228] and the Rojava Revolution in Syria, which established the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) as a "libertarian socialist alternative to the colonially established state boundaries in the Middle East."[228]

In 2022, student activist and self-described libertarian socialist Gabriel Boric became head of state of Chile after winning the 2021 Chilean presidential election with the Apruebo Dignidad coalition.[53][54][55]

In the United States, polls (circa 2006) found that the views and voting habits of between 10% and 20%, or more, of voting age Americans might be classified as "fiscally conservative and socially liberal, or libertarian".[77][125] This was based on pollsters' and researchers' defining libertarian views as fiscally conservative and socially liberal (based on the common United States meanings of the terms) and against government intervention in economic affairs and for expansion of personal freedoms.[77] In a 2015 Gallup poll, this figure had risen to 27%.[133] A 2015 Reuters poll found that 23% of American voters self-identified as libertarians, including 32% in the 18–29 age group.[132] Through twenty polls on this topic spanning thirteen years, Gallup found that voters who are libertarian on the political spectrum ranged from 17–23% of the United States electorate.[130] However, a 2014 Pew Poll found that 23% of Americans who identify as libertarians have no idea what the word means. In this poll, 11% of respondents both identified as libertarians and understand what the term meant.[131]

In 2001, an American political migration movement, called the Free State Project, was founded to recruit at least 20,000 libertarians to move to a single low-population state (New Hampshire, was selected in 2003) in order to make the state a stronghold for libertarian ideas.[229][230] As of May 2022, approximately 6,232 participants have moved to New Hampshire for the Free State Project.[231]

2009 saw the rise of the Tea Party movement, an American political movement known for advocating a reduction in the United States national debt and federal budget deficit by reducing government spending and taxes, which had a significant libertarian component[232] despite having contrasts with libertarian values and views in some areas such as free trade, immigration, nationalism and social issues.[233] A 2011 Reason-Rupe poll found that among those who self-identified as Tea Party supporters, 41 percent leaned libertarian and 59 percent socially conservative.[234] Named after the Boston Tea Party, it also contained populist elements.[235][236] By 2016, Politico noted that the Tea Party movement was essentially completely dead; however, the article noted that the movement seemed to die in part because some of its ideas had been absorbed by the mainstream Republican Party.[237]

In 2012, anti-war and pro-drug liberalization presidential candidates such as Libertarian Republican Ron Paul and Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson raised millions of dollars and garnered millions of votes despite opposition to their obtaining ballot access by both Democrats and Republicans.[238] The 2012 Libertarian National Convention saw Johnson and Jim Gray being nominated as the 2012 presidential ticket for the Libertarian Party, resulting in the most successful result for a third-party presidential candidacy since 2000 and the best in the Libertarian Party's history by vote number. Johnson received 1% of the popular vote, amounting to more than 1.2 million votes.[239][240] Johnson has expressed a desire to win at least 5 percent of the vote so that the Libertarian Party candidates could get equal ballot access and federal funding, thus subsequently ending the two-party system.[241][242][243] The 2016 Libertarian National Convention saw Johnson and Bill Weld nominated as the 2016 presidential ticket and resulted in the most successful result for a third-party presidential candidacy since 1996 and the best in the Libertarian Party's history by vote number. Johnson received 3% of the popular vote, amounting to more than 4.3 million votes.[244] Following the 2022 Libertarian National Convention, the Mises Caucus, a paleolibertarian faction, became the dominant faction on the Libertarian National Committee.[245][246] Right-wing libertarian ideals are also prominent in far-right American militia movement associated with extremist anti-government ideas.[247]

Chicago school of economics economist Milton Friedman made the distinction between being part of the American Libertarian Party and "a libertarian with a small 'l'," where he held libertarian values but belonged to the American Republican Party.[248]

In 2023, Argentine economist Javier Milei became the first openly libertarian head of state,[56] after winning that year's general election with the La Libertad Avanza coalition.[57]

Since the 1950s, many American libertarian organizations have adopted a free-market stance as well as supporting civil liberties and non-interventionist foreign policies. These include the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Francisco Marroquín University, the Foundation for Economic Education, Center for Libertarian Studies, the Cato Institute and Liberty International. The activist Free State Project, formed in 2001, works to bring 20,000 libertarians to New Hampshire to influence state policy.[249] Active student organizations include Students for Liberty and Young Americans for Liberty. A number of countries have libertarian parties that run candidates for political office. In the United States, the Libertarian Party was formed in 1972 and is the third largest[250][251] American political party, with 511,277 voters (0.46% of total electorate) registered as Libertarian in the 31 states that report Libertarian registration statistics and Washington, D.C.[252]

Criticism of libertarianism includes ethical, economic, environmental, pragmatic and philosophical concerns, especially in relation to right-libertarianism,[253] including the view that it has no explicit theory of liberty.[73] It has been argued that laissez-faire capitalism does not necessarily produce the best or most efficient outcome,[254][255] nor does its philosophy of individualism and policies of deregulation prevent the abuse of natural resources.[256]

Critics have accused libertarianism of promoting "atomistic" individualism that ignores the role of groups and communities in shaping an individual's identity.[4] Libertarians have responded by denying that they promote this form of individualism, arguing that recognition and protection of individualism does not mean the rejection of community living.[4] Libertarians also argue that they are simply against individuals' being forced to have ties with communities and that individuals should be allowed to sever ties with communities they dislike and form new communities instead.[4]

Critics such as Corey Robin describe this type of libertarianism as fundamentally a reactionary conservative ideology united with more traditionalist conservative thought and goals by a desire to enforce hierarchical power and social relations.[96] Similarly, Nancy MacLean has argued that libertarianism is a radical right ideology that has stood against democracy. According to MacLean, libertarian-leaning Charles and David Koch have used anonymous, dark money campaign contributions, a network of libertarian institutes and lobbying for the appointment of libertarian, pro-business judges to United States federal and state courts to oppose taxes, public education, employee protection laws, environmental protection laws and the New Deal Social Security program.[257]

Conservative philosopher Russell Kirk argued that libertarians "bear no authority, temporal or spiritual" and do not "venerate ancient beliefs and customs, or the natural world, or [their] country, or the immortal spark in [their] fellow men."[4] Libertarians have responded by saying that they do venerate these ancient traditions, but are against the law's being used to force individuals to follow them.[4]

[L]ibertarianism, political philosophy that takes individual liberty to be the primary political value.

[F]or the very nature of the libertarian attitude—its rejection of dogma, its deliberate avoidance of rigidly systematic theory, and, above all, its stress on extreme freedom of choice and on the primacy of the individual judgement [sic].

One gratifying aspect of our rise to some prominence is that, for the first time in my memory, we, 'our side,' had captured a crucial word from the enemy. 'Libertarians' had long been simply a polite word for left-wing anarchists, that is for anti-private property anarchists, either of the communist or syndicalist variety. But now we had taken it over.

It attacks not only capital, but also the main sources of the power of capitalism: law, authority, and the State.

Libertarianism is committed to full self-ownership. A distinction can be made, however, between right-libertarianism and left-libertarianism, depending on the stance taken on how natural resources can be owned.

In the modern world, political ideologies are largely defined by their attitude towards capitalism. Marxists want to overthrow it, liberals to curtail it extensively, conservatives to curtail it moderately. Those who maintain that capitalism is an excellent economic system, unfairly maligned, with little or no need for corrective government policy, are generally known as libertarians.

Many of us call ourselves 'liberals.' And it is true that the word 'liberal' once described persons who respected the individual and feared the use of mass compulsions. But the leftists have now corrupted that once-proud term to identify themselves and their program of more government ownership of property and more controls over persons. As a result, those of us who believe in freedom must explain that when we call ourselves liberals, we mean liberals in the uncorrupted classical sense. At best, this is awkward and subject to misunderstanding. Here is a suggestion: Let those of us who love liberty trade-mark and reserve for our own use the good and honorable word 'libertarian'.

The leader of the rising Zehut Party is attracting more than just young potheads to his libertarian platform.

[...] and personal liberty. Its platform includes libertarian economic positions [...].

Now you have two special-interest groups. What pulls them together is the strong libertarian, anti-state agenda that works well for both.

Anarcho-capitalism is a variety of libertarianism according to which all government institutions can and should be replaced by private ones.

Howewer, enough has been said to show that most anarchists have nothing in common with those libertarians of the far-right, the anarcho-capitalists [...]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)The term libertarian as used in the US means something quite different from what it meant historically and still means in the rest of the world. Historically, the libertarian movement has been the anti-statist wing of the socialist movement. Socialist anarchism was libertarian socialism.

'[L]ibertarianism' [...] a term that, until the mid-twentieth century, was synonymous with "anarchism" per se.

Depending on the context, libertarianism can be seen as either the contemporary name for classical liberalism, adopted to avoid confusion in those countries where liberalism is widely understood to denote advocacy of expansive government powers, or as a more radical version of classical liberalism.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)An appreciation for spontaneous order can be found in the writings of the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu (6th century bce), who urged rulers to "do nothing" because "without law or compulsion, men would dwell in harmony."

More specifically, I disapprove of, disagree with and have no connection with, the latest aberration of some conservatives, the so-called "hippies of the right," who attempt to snare the younger or more careless ones of my readers by claiming simultaneously to be followers of my philosophy and advocates of anarchism. [...] libertarians are a monstrous, disgusting bunch of people: they plagiarize my ideas when that fits their purpose, and denounce me in a more vicious manner than any communist publication when that fits their purpose.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)Is the Tea Party libertarian? Overall, the Tea Party movement is not libertarian, though it has many libertarian elements, and many libertarians are Tea Partiers. [...] They share the libertarian view that DC tends to be corrupt, and that Washington often promotes special interests at the expense of the common good. However, Tea Party members are predominantly populist, nationalist, social conservatives rather than libertarians. Polls indicate that most Tea Partiers believe government should have an active role in promoting traditional "family values" or conservative Judeo-Christian values. Many of them oppose free trade and open immigration. They tend to favor less government intervention in the domestic economy but more government intervention in international trade.

[...] these militia organizations often revived long-since discarded state militia insignia and organization names while simultaneously aligning them with contemporary far-right libertarian politics (Crothers 2004).

The first, we would call "libertarianism" today. Libertarians wanted to get all government out of people's lives. This movement is still very much alive today. In fact, in the United States, it is the third largest political party, and ran 125 candidates during the U.S. election of 1988.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)