Храмовая гора ( иврит : הַר הַבַּיִת , латинизированное: Хар хаБаит , букв. «Храмовая гора»), также известная как Харам аш-Шариф ( араб . الحرم الشريف, букв. «Благородное святилище»), комплекс мечети аль-Акса , или просто аль-Акса ( / æ l ˈ æ k s ə / ; المسجد الأقصى , аль-Масджид аль-Акса , букв. «Самая дальняя мечеть»), [2] а иногда и как священная эспланада Иерусалима , [3] [4 ] — холм в Старом городе Иерусалима , на котором почиталось как святое место на протяжении тысяч лет, в том числе в иудаизме , христианстве и исламе . [5] [6]

Нынешнее место представляет собой плоскую площадь, окруженную подпорными стенами (включая Западную стену ), которые изначально были построены царем Иродом в первом веке до н. э. для расширения Второго еврейского храма . На площади доминируют два монументальных сооружения, изначально построенных во времена Рашидунского и раннего Омейядского халифатов после захвата города в 637 г. н. э.: [7] главный молитвенный зал мечети Аль-Акса и Купол Скалы , недалеко от центра холма, строительство которого было завершено в 692 г. н. э., что делает его одним из старейших сохранившихся исламских сооружений в мире. Стены и ворота Ирода с дополнениями из поздневизантийского , раннего мусульманского , мамлюкского и османского периодов обрамляют место, куда можно попасть через одиннадцать ворот , десять из которых зарезервированы для мусульман и одни для немусульман, с постами охраны израильской полиции поблизости от каждого. [8] Двор окружен с севера и запада двумя портиками эпохи мамлюков ( риваками ) и четырьмя минаретами .

Храмовая гора является самым святым местом в иудаизме, [9] [10] [a] и где когда-то стояли два еврейских храма. [12] [13] [14] Согласно еврейской традиции и писанию, [15] Первый Храм был построен царем Соломоном , сыном царя Давида , в 957 г. до н. э. и был разрушен Нововавилонской империей вместе с Иерусалимом в 587 г. до н. э. Никаких археологических свидетельств, подтверждающих существование Первого Храма, найдено не было, а научные раскопки были ограничены из-за религиозных соображений. [16] [17] [18] Второй Храм, построенный при Зоровавеле в 516 г. до н. э., позже был отреставрирован царем Иродом и в конечном итоге был разрушен Римской империей в 70 г. н. э. Ортодоксальная еврейская традиция утверждает, что именно здесь будет построен третий и последний Храм , когда придет Мессия . [19] Храмовая гора — это место, к которому евреи обращаются во время молитвы. Отношение евреев к входу на это место различается. Из-за его чрезвычайной святости многие евреи не будут ходить по самой горе, чтобы избежать непреднамеренного входа в область, где стояла Святая Святых , поскольку, согласно раввинскому закону, на этом месте все еще есть некий аспект божественного присутствия . [20] [21] [22]

Комплекс мечети Аль-Акса , расположенный на вершине, является второй старейшей мечетью в исламе [ 23] и одной из трех Священных мечетей, самых святых мест в исламе ; она почитается как «Благородное святилище». [24] Ее двор ( сахн ) [25] может вместить более 400 000 верующих, что делает ее одной из крупнейших мечетей в мире [23] Для мусульман- суннитов и шиитов она занимает третье место по святости в исламе . Площадь включает место, которое считается местом, где исламский пророк Мухаммед вознесся на небеса [26], и служила первой « киблой », направлением, в котором мусульмане обращаются во время молитвы. Как и в иудаизме, мусульмане также связывают это место с Соломоном и другими пророками, которые также почитаются в исламе. [27] Место и термин «Аль-Акса» по отношению ко всей площади также являются центральным символом идентичности для палестинцев , включая палестинских христиан . [28] [29] [30]

Со времен крестовых походов мусульманская община Иерусалима управляла этим местом через Иерусалимский исламский вакф . Это место, как и весь Восточный Иерусалим (включая Старый город), контролировалось Иорданией с 1948 по 1967 год и было оккупировано Израилем после Шестидневной войны 1967 года. Вскоре после захвата этого места Израиль передал его управление обратно вакфу под опеку иорданских хашимитов , сохранив при этом контроль безопасности Израиля. [31] Израильское правительство вводит запрет на молитву немусульман в рамках соглашения, обычно называемого «статус-кво». [32] [33] [34] Это место остается основным очагом израильско -палестинского конфликта . [35]

Название места оспаривается, в первую очередь, между мусульманами и евреями, в контексте продолжающегося израильско-палестинского конфликта . Некоторые арабо-мусульманские комментаторы и ученые пытаются отрицать еврейскую связь с Храмовой горой , в то время как некоторые еврейские комментаторы и ученые пытаются принизить важность этого места в исламе. [36] [37] Во время спора 2016 года по поводу названия места Генеральный директор ЮНЕСКО Ирина Бокова заявила: «Разные народы поклоняются одним и тем же местам, иногда под разными названиями. Признание, использование и уважение этих названий имеют первостепенное значение». [38]

Термин Har haBayīt – обычно переводимый как «Храмовая гора» на английском языке – впервые был использован в книгах Михея (4:1) и Иеремии (26:18), буквально как «Гора Дома», литературный вариант более длинной фразы «Гора Дома Господня». Сокращение больше не использовалось в более поздних книгах еврейской Библии [39] или в Новом Завете . [40] Термин оставался в употреблении на протяжении всего периода Второго Храма , хотя термин «Гора Сион», который сегодня относится к восточному холму древнего Иерусалима, использовался чаще. Оба термина используются в Книге Маккавеев . [41] Термин Har haBayīt используется в Мишне и более поздних текстах Талмуда. [42] [43]

Точный момент, когда впервые возникла концепция Горы как топографической особенности, отдельной от Храма или самого города, является предметом споров среди ученых. [41] По словам Элиава, это произошло в первом веке н. э., после разрушения Второго Храма. [44] Шахар и Шацман пришли к разным выводам. [45] [46] В Книгах Паралипоменон , отредактированных в конце персидского периода , гора уже упоминается как отдельное образование. Во 2 Паралипоменон Храм Соломона был построен на горе Мориа (3:1), а искупление Манассией своих грехов связано с Горой Дома Господня (33:15). [47] [48] [41] Концепция Храма как находящегося на святой горе, обладающей особыми качествами, неоднократно встречается в Псалмах, при этом окружающая территория считается неотъемлемой частью самого Храма. [49]

Правительственная организация, которая управляет объектом, Иерусалимский исламский вакф (часть иорданского правительства), заявила, что название «Храмовая гора» является «странным и чуждым названием» и «новопридуманным термином иудаизации». [50] В 2014 году Организация освобождения Палестины (ООП) выпустила пресс-релиз, призывающий журналистов не использовать термин «Храмовая гора» при упоминании объекта. [51] В 2017 году сообщалось, что должностные лица Вакфа преследовали археологов, таких как Габриэль Баркай , и гидов, которые использовали этот термин на объекте. [52] По словам Яна Турека и Джона Кармана, в современном использовании термин Храмовая гора может потенциально подразумевать поддержку израильского контроля над объектом. [53]

2 Паралипоменон 3:1 [47] относится к Храмовой горе во времена до строительства храма как к горе Мориа ( иврит : הַר הַמֹּורִיָּה , har ha-Môriyyāh ).

Несколько отрывков в еврейской Библии указывают на то, что во времена, когда они были написаны, Храмовая гора была идентифицирована как гора Сион. [54] Гора Сион, упомянутая в более поздних частях Книги Исайи (Исайя 60:14), [55] в Книге Псалмов и Первой книге Маккавеев ( ок. 2 в. до н. э. ), по-видимому, относится к вершине холма, обычно известной как Храмовая гора. [54] Согласно Книге Самуила , гора Сион была местом расположения иевусейской крепости, называемой «крепостью Сиона», но как только Первый Храм был возведен, согласно Библии, на вершине Восточного холма («Храмовая гора»), название «гора Сион» переместилось и туда. [54] Позже название переместилось в последний раз, на этот раз на Западный холм Иерусалима. [54]

.jpg/440px-Mesjid_el-Aksa_and_Jami_el-Aksa_in_the_1841_Aldrich_and_Symonds_map_of_Jerusalem_(cropped).jpg)

Английский термин «мечеть аль-Акса» является переводом либо аль-Масджид аль-Акса ( арабский : ٱلْمَسْجِد ٱلْأَقْصَىٰ ), либо аль-Джами аль-Акса ( арабский ٱلْـجَـامِـع) . الْأَقْـصّى ). [56] [57] [58] Аль-Масджид аль-Акса – «самая дальняя мечеть» – происходит от суры 17 Корана («Ночное путешествие»), в которой говорится, что Мухаммед путешествовал из Мекки в мечеть, откуда он впоследствии вознесся на Небеса . [59] [60] Арабские и персидские писатели, такие как географ 10-го века Аль-Макдиси , [61] ученый 11-го века Насир Хусрав , [61] географ 12-го века Мухаммад аль-Идриси [62] и исламский ученый 15-го века Муджир ад-Дин , [63] [64], а также американские и британские востоковеды 19-го века Эдвард Робинсон , [56] Гай Ле Стрейндж и Эдвард Генри Палмер объяснили, что термин Масджид аль-Акса относится ко всей площади эспланады, которая является Предметом этой статьи является вся территория, включая Купол Скалы , фонтаны, ворота и четыре минарета , поскольку ни одно из этих зданий не существовало во времена написания Корана. [57] [65] [66]

Аль-Джами аль-Акса относится к конкретному месту расположения соборной мечети с серебряным куполом [56] [57] [58], также называемой мечетью Кибли или часовней Кибли ( аль-Джами аль-Акса или аль-Кибли , или Масджид аль-Джума или аль-Мугхата ), в связи с ее расположением на южной оконечности комплекса в результате перемещения исламской киблы из Иерусалима в Мекку. [67] Два разных арабских термина, переведенных как «мечеть» на английском языке, параллельны двум разным греческим терминам, переведенным как «храм» в Новом Завете : греческий : ίερόν , романизированный : hieron (эквивалент Masjid) и греческий : ναός , романизированный : naos (эквивалент Jami'a), [56] [63] [68] и использование термина «мечеть» для всего комплекса следует использованию того же термина для других ранних исламских мест с большими дворами, таких как мечеть Ибн Тулуна в Каире, мечеть Омейядов в Дамаске и Великая мечеть Кайруана . [69] Другие источники и карты использовали термин аль-Масджид аль-Акса для обозначения самой соборной мечети. [70] [71] [72]

.jpg/440px-Solomon's_Stables_in_the_1936_Old_City_of_Jerusalem_map_by_Survey_of_Palestine_map_1-2,500_(cropped).jpg)

Термин «аль-Акса» как символ и торговая марка стал популярным и распространенным в регионе. [73] Например, интифада Аль-Акса (восстание в сентябре 2000 года), бригады мучеников Аль-Аксы (коалиция палестинских националистических ополчений на Западном берегу), телевидение Аль-Акса (официальный телеканал ХАМАС), университет Аль-Акса (палестинский университет, основанный в 1991 году в секторе Газа), Джунд аль-Акса (салафитская джихадистская организация, действовавшая во время гражданской войны в Сирии), иорданское военное периодическое издание, издаваемое с начала 1970-х годов, а также объединения как южной, так и северной ветвей Исламского движения в Израиле — все они названы Аль-Акса в честь этого места. [73]

В период правления мамлюков [74] (1260–1517) и османов (1517–1917) более обширный комплекс стал также широко известен как Харам аль-Шариф или аль-Харам аш-Шариф (араб. اَلْـحَـرَم الـشَّـرِيْـف ), что переводится как «Благородное святилище». Это отражает терминологию Масджид аль-Харам в Мекке ; [75] [76] [77] [78] Этот термин возвысил комплекс до статуса Харама , который ранее был зарезервирован для Масджид аль-Харам в Мекке и Аль-Масджид ан-Набави в Медине . Другие исламские деятели оспаривали статус харам этого места. [73] Использование названия Харам аль-Шариф местными палестинцами в последние десятилетия пошло на убыль в пользу традиционного названия мечети Аль-Акса. [73]

Некоторые ученые использовали термины Священная Эспланада или Святая Эспланада как «строго нейтральный термин» для этого места. [5] [6] Ярким примером такого использования является работа 2009 года « Там, где встречаются Небеса и Земля: Священная Эспланада Иерусалима » , написанная в рамках совместного проекта 21 еврейского, мусульманского и христианского ученых. [79] [80]

В последние годы термин «Священная Эспланада» использовался Организацией Объединенных Наций , ее Генеральным секретарем и вспомогательными органами ООН. [81]

Храмовая гора образует северную часть узкого отрога холма, который круто спускается с севера на юг. Возвышаясь над долиной Кедрон на востоке и долиной Тиропеон на западе, [82] ее вершина достигает высоты 740 м (2428 футов) над уровнем моря. [83] Около 19 г. до н. э. Ирод Великий расширил естественное плато горы , окружив территорию четырьмя массивными подпорными стенами и заполнив пустоты. Это искусственное расширение привело к образованию большого плоского пространства, которое сегодня образует восточную часть Старого города Иерусалима . Платформа в форме трапеции имеет размеры 488 м (1601 фут) вдоль запада, 470 м (1540 футов) вдоль востока, 315 м (1033 фута) вдоль севера и 280 м (920 футов) вдоль юга, что дает общую площадь приблизительно 150 000 м 2 (37 акров). [84] Северная стена горы вместе с северной частью западной стены скрыта за жилыми зданиями. Южная часть западного фланга открыта и содержит то, что известно как Западная стена . Подпорные стены с этих двух сторон спускаются на много метров ниже уровня земли. Северную часть западной стены можно увидеть из туннеля Западной стены , который был выкопан через здания, прилегающие к платформе. С южной и восточной сторон стены видны почти во всю свою высоту. Сама платформа отделена от остальной части Старого города долиной Тиропеон, хотя эта некогда глубокая долина теперь в значительной степени скрыта под более поздними отложениями и местами незаметна. На платформу можно попасть через Ворота Цепной улицы — улицу в мусульманском квартале на уровне платформы, фактически сидящую на монументальном мосту; [85] [ нужен лучший источник ] мост больше не виден снаружи из-за изменения уровня земли, но его можно увидеть снизу через туннель Западной стены. [86]

В 1980 году Иордания предложила включить Старый город в список объектов Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО [87] , и он был добавлен в список в 1981 году . [88] В 1982 году он был добавлен в Список объектов Всемирного наследия, находящихся под угрозой . [89]

26 октября 2016 года ЮНЕСКО приняла Резолюцию об оккупированной Палестине , в которой осуждалось то, что она описала как «эскалацию израильской агрессии» и незаконные меры против вакфа, содержался призыв к восстановлению доступа мусульман и требование к Израилю уважать исторический статус-кво [90] [91] [92] , а также критика Израиля за его постоянный «отказ предоставить экспертам организации доступ к святым местам Иерусалима для определения их статуса сохранности». [93] [94] Хотя в тексте признавалась «важность Старого города Иерусалима и его стен для трех монотеистических религий», в нем упоминался священный комплекс на вершине холма в Старом городе Иерусалима только под его мусульманским названием Аль-Харам аш-Шариф.

В ответ Израиль осудил резолюцию ЮНЕСКО за отсутствие в ней слов «Храмовая гора» или «Хар Ха-Байт», заявив, что она отрицает еврейские связи с этим местом. [92] [95] Израиль заморозил все связи с ЮНЕСКО. [96] [97] В октябре 2017 года Израиль и США объявили о выходе из ЮНЕСКО, сославшись на антиизраильскую предвзятость. [98] [99]

6 апреля 2022 года ЮНЕСКО единогласно приняла резолюцию, повторяющую все 21 предыдущую резолюцию, касающуюся Иерусалима. [100]

Храмовая гора имеет историческое и религиозное значение для всех трех основных авраамических религий : иудаизма, христианства и ислама. Она имеет особое религиозное значение для иудаизма и ислама.

Храмовая гора считается самым святым местом в иудаизме. [101] [102] [11] Согласно еврейской традиции, оба Храма стояли на Храмовой горе. [103] Еврейская традиция далее помещает Храмовую гору как место для ряда важных событий, которые произошли в Библии, включая связывание Исаака , сон Иакова и молитву Исаака и Ревекки . [104] Согласно Талмуду, Краеугольный камень - это место, из которого мир был создан и расширен до его нынешнего вида. [105] [106] Ортодоксальная еврейская традиция утверждает, что именно здесь будет построен третий и последний Храм , когда придет Мессия . [107]

Храмовая гора — это место, к которому евреи обращаются во время молитвы. Отношение евреев к входу на это место разное. Из-за его чрезвычайной святости многие евреи не будут ходить по самой горе, чтобы избежать непреднамеренного входа в область, где стояла Святая Святых , поскольку, согласно раввинскому закону, на этом месте все еще присутствует некий аспект божественного присутствия . [108] [109] [110]

Согласно еврейской Библии , Храмовая гора изначально была гумном, принадлежавшим Орне , иевусею . [ 111] Библия повествует о том, как Давид объединил двенадцать израильских колен , завоевал Иерусалим и принес в город главный артефакт израильтян , Ковчег Завета . [112] Когда великая чума поразила Израиль, на гумне Орны появился ангел-губитель . Затем пророк Гад предложил Давиду это место как подходящее место для возведения алтаря Яхве . [113] Давид купил собственность у Орны за пятьдесят сребреников и воздвиг алтарь. Бог ответил на его молитвы и остановил чуму. Впоследствии Давид выбрал место для будущего храма, чтобы заменить Скинию и разместить Ковчег Завета; [114] [115] Однако Бог запретил ему строить его, потому что он «пролил много крови». [116]

Первый Храм был построен при сыне Давида Соломоне , [117] который стал амбициозным строителем общественных сооружений в древнем Израиле : [118]

Тогда Соломон начал строить дом Господень в Иерусалиме на горе Мориа, где явился [Господь] Давиду, отцу его; для этого был приготовлен дом на месте Давидовом, на гумне Орны Иевусеянина.

— 2 Паралипоменон 3:1 [119]

Соломон поместил Ковчег в Святая Святых — самое внутреннее святилище без окон и самую священную часть храма, в которой покоилось присутствие Бога; [120] вход в Святая Святых был строго ограничен, и только первосвященник Израиля входил в святилище один раз в год на Йом-Киппур , неся кровь жертвенного агнца и сжигая благовония . [120] Согласно Библии, это место функционировало как центр всей национальной жизни — правительственный, судебный и религиозный центр. [121]

В книге Бытие Рабба , написанной, вероятно, между 300 и 500 годами н. э., говорится, что это место является одним из трех, о которых народы мира не могут насмехаться над Израилем и говорить: «Ты украл их», поскольку оно было куплено «за полную цену» Давидом. [122]

Первый Храм был разрушен в 587/586 г. до н. э. Нововавилонской империей под руководством второго вавилонского царя Навуходоносора II , который впоследствии изгнал иудеев в Вавилон после падения Иудейского царства и его аннексии в качестве вавилонской провинции . Евреям, которые были депортированы после вавилонского завоевания Иудеи, в конечном итоге было разрешено вернуться после провозглашения персидского царя Кира Великого , которое было выпущено после падения Вавилона империей Ахеменидов . В 516 г. до н. э. вернувшееся еврейское население Иудеи под персидским провинциальным управлением восстановило Храм в Иерусалиме под эгидой Зоровавеля , создав то, что известно как Второй Храм .

В период Второго Храма Иерусалим был центром религиозной и национальной жизни евреев, в том числе и в диаспоре . [123] Считается, что Второй Храм привлек десятки, а может быть, и сотни тысяч людей во время Трех Паломнических Праздников . [123] Праздник Ханука отмечает повторное освящение Храма в начале восстания Маккавеев во II веке до н. э. В I веке до н. э. Храм был восстановлен Иродом . Он был разрушен Римской империей в разгар Первой иудейско-римской войны в 70 году н. э. Тиша бе-Ав , ежегодный день поста в иудаизме , знаменует разрушение Первого и Второго Храмов, которое, согласно еврейской традиции, произошло в один и тот же день по еврейскому календарю .

В Книге пророка Исайи предсказывается международное значение Храмовой горы:

И будет в конце дней, гора дома Господня будет поставлена во главу гор и возвысится над холмами, и потекут к ней все народы. И пойдут многие народы и скажут: «Придите, и взойдем на гору Господню, в дом Бога Иаковлева, и научит Он нас путям Своим, и будем ходить по стезям Его». Ибо от Сиона выйдет закон, и слово Господне — из Иерусалима.

— Исаия 2:2–3 [124]

В еврейской традиции Храмовая гора также считается местом, где Авраам связал Исаака . 2 Паралипоменон 3:1 [47] упоминает Храмовую гору во времена до строительства храма как гору Мориа ( иврит : הַר הַמֹּורִיָּה , har ha-Môriyyāh ). « Земля Мориа » ( אֶרֶץ הַמֹּרִיָּה , eretṣ ha-Môriyyāh ) — это название, данное в Книге Бытия месту связывания Исаака. [125] Начиная, по крайней мере, с первого века нашей эры, эти два места отождествлялись друг с другом в иудаизме, и это отождествление впоследствии было увековечено еврейской и христианской традицией . Современная наука склонна рассматривать их как отдельные горы (см. Мориа ).

По мнению раввинских мудрецов, дебаты которых породили Талмуд , Краеугольный камень , который находится под Куполом Скалы , был местом, откуда мир был создан и расширился до его нынешнего вида, [105] [106] и где Бог собрал пыль, использованную для создания первого человека, Адама . [125]

Еврейские тексты предсказывают, что Гора станет местом Третьего и последнего Храма , который будет восстановлен с пришествием Мессии . Восстановление Храма оставалось повторяющейся темой среди поколений, особенно в трижды в день Амида (стоячая молитва), центральной молитве еврейской литургии , которая содержит призыв к строительству Третьего Храма и восстановлению жертвенных служб . Ряд активных еврейских групп теперь выступают за строительство Третьего Храма без промедления, чтобы осуществить «пророческие планы Бога на конец света для Израиля и всего мира». [126]

Храм имел центральное значение в иудейском богослужении в Танахе ( Ветхом Завете ). В Новом Завете Храм Ирода был местом нескольких событий в жизни Иисуса , и христианская верность этому месту как центральной точке сохранялась еще долгое время после его смерти. [127] [128] [129] После разрушения Храма в 70 г. н. э., которое стало рассматриваться ранними христианами, как и Иосифом Флавием и мудрецами Иерусалимского Талмуда , как божественный акт наказания за грехи еврейского народа, [130] [131] Храмовая гора утратила свое значение для христианского богослужения, поскольку христиане считали ее исполнением пророчества Христа, например, в Евангелии от Матфея 23:38 [132] и Матфея 24:2. [133] Именно с этой целью, в качестве доказательства исполнения библейского пророчества и победы христианства над иудаизмом с Новым Заветом , [134] ранние христианские паломники также посещали это место. [135] Византийские христиане, несмотря на некоторые признаки конструктивной работы на эспланаде, [136] обычно пренебрегали Храмовой горой, особенно когда попытка евреев восстановить Храм была разрушена землетрясением 363 года . [137] Она стала заброшенной местной свалкой, возможно, за пределами городской черты, [138] поскольку христианское богослужение в Иерусалиме переместилось в Храм Гроба Господня , а центральное положение Иерусалима было заменено Римом. [139]

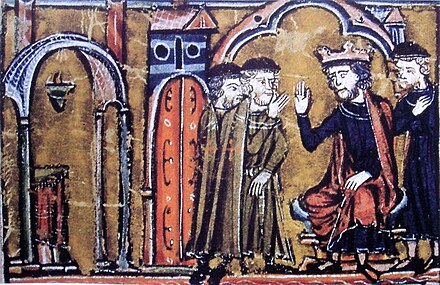

В византийскую эпоху Иерусалим был в основном христианским, и паломники приезжали десятками тысяч, чтобы увидеть места, где ходил Иисус. [ требуется цитата ] После персидского вторжения в 614 году многие церкви были разрушены, а это место было превращено в свалку. Арабы отвоевали город у Византийской империи, которая вернула его в 629 году. Византийский запрет на евреев был снят, и им было разрешено жить в городе и посещать места поклонения. Христианские паломники могли приезжать и исследовать район Храмовой горы. [140] Война между сельджуками и Византийской империей и растущее мусульманское насилие против христианских паломников в Иерусалиме спровоцировали крестовые походы . Крестоносцы захватили Иерусалим в 1099 году, и Купол Скалы был передан августинцам , которые превратили его в церковь, а мечеть Аль-Акса стала королевским дворцом Балдуина I Иерусалимского в 1104 году. Тамплиеры , считавшие, что Купол Скалы был местом расположения Храма Соломона , дали ему название « Templum Domini » и разместили свою штаб-квартиру в мечети Аль-Акса, прилегающей к Куполу, на большую часть XII века. [ необходима ссылка ]

В христианском искусстве обрезание Иисуса традиционно изображалось происходящим в Храме, хотя европейские художники до недавнего времени не имели возможности узнать, как выглядел Храм, а в Евангелиях не говорится, что это событие произошло в Храме. [141]

Хотя некоторые христиане верят, что Храм будет восстановлен до или одновременно со Вторым пришествием Иисуса (см. также диспенсационализм ), паломничество на Храмовую гору не рассматривается как важное в верованиях и поклонении большинства христиан. В Новом Завете рассказывается история о самаритянке, которая спросила Иисуса о подходящем месте для поклонения, Иерусалиме (как это было для иудеев) или горе Гаризим (как это было для самаритян ), на что Иисус отвечает:

Женщина, поверь мне, наступает время, когда и на горе сей, и в Иерусалиме не будете поклоняться Отцу. Вы не знаете, чему поклоняетесь, а мы знаем, чему поклоняемся, ибо спасение от Иудеев. Но настанет время и настало уже, когда истинные поклонники будут поклоняться Отцу в духе и истине, ибо таких поклонников Отец ищет Себе. Бог есть дух, и поклоняющиеся Ему должны поклоняться в духе и истине.

— Иоанна 4:21–24 [142]

Это было истолковано как то, что Иисус обошелся без физического места для поклонения, что было скорее вопросом духа и истины. [143]

.jpg/440px-Dan_Hadani_collection_(990040387040205171).jpg)

Среди мусульман- суннитов и шиитов [ требуется ссылка ] вся площадь, известная как мечеть аль-Акса, также известная как Харам аш-Шариф или «Благородное святилище», считается третьим по святости местом в исламе . [24] Согласно исламской традиции, площадь является местом вознесения Мухаммеда на небеса из Иерусалима и служила первой « киблой », направлением, в котором мусульмане обращаются во время молитвы. Как и в иудаизме, мусульмане также связывают это место с Авраамом и другими пророками, которые также почитаются в исламе. [27] Мусульмане рассматривают это место как одно из самых ранних и самых примечательных мест поклонения Богу . Они предпочли использовать эспланаду в качестве сердца для мусульманского квартала, поскольку она была заброшена христианами, чтобы не беспокоить христианские кварталы Иерусалима. [144] Омейядские халифы заказали строительство мечети Аль-Акса на этом месте, включая святилище, известное как « Купол Скалы ». [145] Купол был завершен в 692 году н. э., что делает его одним из старейших сохранившихся исламских сооружений в мире. Мечеть Аль-Акса , иногда известная как мечеть Кибли, находится на дальней южной стороне горы, обращенной к Мекке .

Ранний ислам считал Краеугольный камень местом расположения Храма Соломона, и первые архитектурные инициативы на Храмовой горе стремились прославить Иерусалим, представляя ислам как продолжение иудаизма и христианства. [36] Почти сразу после завоевания Иерусалима мусульманами в 638 году н. э. халиф Омар ибн аль-Хатаб , как сообщается, испытывавший отвращение к грязи, покрывавшей это место, приказал его тщательно очистить [146] и предоставил евреям доступ к этому месту. [147] Согласно ранним толкователям Корана и общепринятой исламской традиции, в 638 году н. э. Умар, войдя в завоеванный Иерусалим, посоветовался с Каабом аль-Ахбаром — иудеем, принявшим ислам и пришедшим с ним из Медины , — о том, где лучше всего построить мечеть. Аль-Ахбар предложил ему построить ее за Скалой «... чтобы весь Иерусалим был перед тобой». Умар ответил: «Ты соответствуешь иудаизму!» Сразу после этого разговора Умар начал убирать место, которое было заполнено мусором и обломками, своим плащом, и другие мусульманские последователи подражали ему, пока место не стало чистым. Затем Умар помолился на том месте, где, как считалось, Мухаммед молился перед своим ночным путешествием, прочитав кораническую суру Сад . [148] Таким образом, согласно этой традиции, Умар тем самым повторно освятил место как мечеть. [149]

Мусульманские толкования Корана сходятся во мнении, что Гора является местом расположения Храма, первоначально построенного Соломоном , считающимся пророком в исламе , который позже был разрушен. [150] [151] После строительства, как верят мусульмане, храм использовался для поклонения единому Богу многими пророками ислама, включая Иисуса. [152] [153] [154] Другие мусульманские ученые использовали Тору (на арабском языке называемую Таурат ), чтобы расширить детали храма. [155] Термин Байт аль-Макдис (или Байт аль-Мукаддас ), который часто появляется как название Иерусалима в ранних исламских источниках, является родственным еврейскому термину bēt ha-miqdāsh (בית המקדש), Храм в Иерусалиме. [156] [157] [158] Муджир ад-Дин , иерусалимский летописец XV века, упоминает более раннюю традицию, переданную аль-Васти, согласно которой «после того, как Давид построил много городов и положение детей Израиля улучшилось, он захотел построить Байт аль-Макдис и возвести купол над скалой в месте, которое Аллах освятил в Элии». [36]

Согласно Корану , Мухаммед был перенесен в место под названием Мечеть Аль-Акса – «самое дальнее место молитвы» ( аль-Масджид аль-Акса ) во время своего Ночного путешествия ( Исра и Мирадж ). [159] Коран описывает, как Мухаммед был доставлен чудесным конем Бураком из Великой мечети Мекки в мечеть Аль-Акса, где он молился. [160] [159] [161] После того, как Мухаммед закончил свои молитвы, ангел Джибрил ( Гавриил ) отправился с ним на небеса, где он встретил нескольких других пророков и возглавил их в молитве: [162] [163] [164]

Слава Тому, Кто перенес Своего раба Мухаммада ночью из Заповедной мечети в Отдалённую мечеть, окрестности которой Мы благословили, чтобы показать ему некоторые из Наших знамений. Воистину, Он один — Всеслышащий, Всевидящий.

— Сура Аль-Исра 17:1

Коран не упоминает точное местоположение «самого дальнего места молитвы», и город Иерусалим не упоминается ни под одним из своих названий в Коране. [165] [151] Согласно Энциклопедии ислама , эта фраза изначально понималась как ссылка на место на небесах. [166] Группа исламских ученых поняла историю вознесения Мухаммеда из мечети Аль-Акса как относящуюся к иудейскому храму в Иерусалиме . Другая группа не согласилась с этой идентификацией и предпочла значение термина как относящееся к небесам. [167] Аль-Бухари и Ат-Табари , например, как полагают, отвергли идентификацию с Иерусалимом. [166] [168] В конце концов, возник консенсус вокруг идентификации «самого дальнего места молитвы» с Иерусалимом и, как следствие, с Храмовой горой. [167] [169] Более поздние хадисы упоминают Иерусалим как место расположения мечети Аль-Акса: [170]

Сообщается, что Джабир ибн Абдуллах сказал:

«Он слышал, как Посланник Аллаха сказал: «Когда курайшиты не поверили мне (в историю моего ночного путешествия), я встал в Хиджре, и Аллах показал мне Иерусалим, и я начал описывать его им, глядя на него».— Сахих аль-Бухари 3886

Некоторые ученые указывают на политические мотивы династии Омейядов , которые привели к освящению Иерусалима в исламе. Согласно «Энциклопедии ислама», Ночное путешествие было связано Омейядами с Иерусалимом как политическое средство для продвижения славы Иерусалима, чтобы конкурировать со славой святилища в Мекке, тогда контролируемой Абдаллахом ибн аль-Зубайром . [166] [171] Строительство Купола Скалы было истолковано Якуби , историком Аббасидов IX века , как попытка Омейядов перенаправить хадж из Мекки в Иерусалим, создав соперника Каабе . [ 172]

Другие ученые приписывают святость Иерусалима возникновению и расширению определенного типа литературного жанра, известного как аль-Фадаль или история городов. Фадаль Иерусалима вдохновлял мусульман, особенно в период Омейядов, приукрашивать святость города за пределами его статуса в священных текстах. [173] Основываясь на трудах историков восьмого века Аль-Вакиди [174] и аль-Азраки , некоторые ученые предположили, что мечеть Аль-Акса, упомянутая в Коране, находится не в Иерусалиме, а в деревне Аль-Джурана , в 18 милях к северо-востоку от Мекки. [168] [175] [176]

Более поздние средневековые рукописи, а также современные политические трактаты, как правило, классифицируют мечеть Аль-Акса как третье по значимости святое место в исламе. [177]

Историческое значение мечети Аль-Акса в исламе еще больше подчеркивается тем фактом, что мусульмане обращались к Аль-Аксе, когда молились в течение 16 или 17 месяцев после переселения в Медину в 624 году; таким образом, она стала киблой («направлением»), в которое мусульмане обращались для молитвы. [178] Позже Мухаммед молился в направлении Каабы в Мекке после получения откровения во время молитвенной сессии [179] [180] в Масджид аль-Киблатайн . [181] [182] Кибла была перенесена в Каабу , где мусульманам было предписано молиться с тех пор. [183]

Организация исламского сотрудничества называет мечеть Аль-Акса третьим по значимости местом в исламе (и призывает к арабскому суверенитету над ней). [184]

Считается, что холм был заселен с 4-го тысячелетия до н. э . [ необходима ссылка ] Амулет с картушем Тутмоса III (годы правления 1479–1425 до н. э.) был обнаружен на этом месте в 2012 году в ходе проекта по просеиванию на Храмовой горе . [185]

По мнению археологов, Храмовая гора служила центром религиозной жизни библейского Иерусалима, а также королевским акрополем Иудейского царства . [186] Считается, что Первый Храм когда-то был частью гораздо более крупного королевского комплекса. [187] В Библии также упоминается несколько других зданий, построенных Соломоном на этом месте, включая королевский дворец, «Дом Ливанского леса», «Зал колонн», «Тронный зал» и «Дом дочери фараона». [41] [188] Некоторые ученые полагают, что, в соответствии с библейскими рассказами, королевский и религиозный комплекс на Храмовой горе был построен Соломоном в 10 веке до н. э. как отдельное образование, которое позже было включено в город. [186] Кнауф утверждал, что Храмовая гора уже служила культовым и правительственным центром Иерусалима еще в позднем бронзовом веке . [189] В качестве альтернативы Нееман предположил, что Соломон построил Храм в гораздо меньших масштабах, чем тот, что описан в Библии, который был расширен или перестроен в 8 веке до н. э. [190] В 2014 году Финкельштейн , Кох и Липшиц предположили , что руины древнего Иерусалима находятся под современным комплексом, а не на близлежащем археологическом объекте, известном как Город Давида , как полагает основная археология; [191] однако это предложение было отвергнуто другими исследователями этого вопроса. [192]

Все ученые сходятся во мнении, что Храмовая гора железного века была меньше, чем комплекс Ирода, который все еще виден сегодня. Некоторые ученые, такие как Кеньон и Ритмейер , утверждали, что стены комплекса Первого Храма простирались на восток до Восточной стены . [186] [187] Ритмейер идентифицирует определенные ряды видимых тесаных камней, расположенных к северу и югу от Золотых ворот , как иудейские железные века по стилю, датируя их строительством этой стены Езекией . Предполагается, что под землей сохранилось больше таких камней. [193] [194] Ритмейер также предположил, что одна из ступеней, ведущих к Куполу Скалы, на самом деле является вершиной оставшегося каменного ряда западной стены комплекса железного века. [195] [196]

Первый Храм был разрушен в 587/586 г. до н. э. Нововавилонской империей под предводительством Навуходоносора II .

Строительство Второго Храма началось при Кире около 538 г. до н. э. и было завершено в 516 г. до н. э. Он был построен на месте первоначального Храма Соломона. [197] [41]

По мнению Патриха и Эделькоппа, идеальная площадь комплекса, описанная у Иезекииля как 50x50 локтей, была достигнута Хасмонеями , возможно, при Иоанне Гиркане ; это тот же размер, который позже упоминается в Мишне . [41]

Археолог Лин Ритмейер обнаружила доказательства расширения Храмовой горы династией Хасмонеев .

В 67 г. до н. э. между Аристобулом II и Гирканом II на троне Хасмонеев вспыхнула ссора . Римский полководец Помпей , которого пригласили вмешаться в конфликт, встал на сторону Гиркана; Аристобул и его последователи забаррикадировались внутри Храмовой горы и разрушили мост, соединяющий ее с городом. Когда римская армия прибыла в Иерусалим, Помпей приказал засыпать ров, защищающий Храмовую гору с севера. Чтобы добиться этого, Помпей дождался субботы , чтобы защитники не мешали работе. После трехмесячной осады римляне смогли снести одну из сторожевых башен и штурмовать Храмовую гору. Сам Помпей вошел в Святая Святых , но не нанес вреда Храму и позволил священникам продолжить свою работу как обычно. [198] [199] [200]

Около 19 г. до н. э. Ирод Великий еще больше расширил Храмовую гору и перестроил храм . Амбициозный проект, в котором было задействовано 10 000 рабочих, [201] более чем вдвое увеличил площадь Храмовой горы до приблизительно 36 акров (150 000 м 2 ). Ирод выровнял территорию, срезав скалу на северо-западной стороне и подняв наклонную поверхность на юге. Он добился этого, построив огромные контрфорсные стены и своды и заполнив необходимые секции землей и щебнем. [202] Результатом стал самый большой теменос в древнем мире. [203]

Главными входами на Храмовую гору Ирода были два набора ворот, встроенных в южную стену, вместе с четырьмя другими воротами, к которым можно было добраться с западной стороны по лестницам и мостам. Грандиозные стоа окружали платформу с трех сторон, а на ее южной стороне стояла великолепная базилика, которую Иосиф Флавий называл Царской стоа . [203] Царская стоа служила центром для коммерческих и юридических операций города и имела отдельный доступ к городу ниже через эстакаду Арки Робинсона . [204] Сам Храм и его дворы располагались на возвышенной платформе в середине большего комплекса. В дополнение к восстановлению Храма, его дворов и портиков, Ирод также построил крепость Антония , которая доминировала в северо-западном углу Храмовой горы, и резервуар для дождевой воды, Биркет Исраэль , на северо-востоке. Монументальная улица, сегодня называемая « Ступенчатой улицей », вела паломников от южных ворот города через долину Тиропеон к западной стороне Храмовой горы. В 2019 году было высказано предположение, что Понтий Пилат построил дорогу в 30-х годах. [205]

На ранних этапах Первой иудейско-римской войны (66–70 гг. н. э.) Храмовая гора стала центром сражений различных еврейских фракций, боровшихся за контроль над городом, причем разные фракции удерживали эту территорию во время конфликта. В апреле 70 г. римская армия под командованием Тита достигла Иерусалима и начала осаду города . Римлянам потребовалось четыре месяца, чтобы победить защитников Храмовой горы и захватить это место. Римляне полностью разрушили Храм и все другие сооружения на платформе. [206] Были обнаружены массивные каменные обрушения с верхних стен, лежащие над улицей Ирода, которая проходит вдоль южной части Западной стены, [207] причем некоторые из камней обжигались при температурах, достигающих 800 °C (1472 °F). [208] Надпись Trumpeting Place , монументальная еврейская надпись, которая была сброшена римскими легионерами, была найдена в одной из этих каменных груд. [209]

Город Элия Капитолина был построен в 130 году н. э. римским императором Адрианом и занят римской колонией на месте Иерусалима, который все еще лежал в руинах после Первого еврейского восстания в 70 году н. э. Элия произошла от имени Адриана , Элий , в то время как Капитолина означала, что новый город был посвящен Юпитеру Капитолийскому , храм которого был построен на месте бывшего второго еврейского храма, Храмовой горы. [210]

Адриан намеревался построить новый город в качестве подарка евреям, но поскольку он воздвиг гигантскую статую самого себя перед храмом Юпитера, а в храме Юпитера находилась огромная статуя Юпитера, на Храмовой горе теперь было два огромных идола , которые евреи считали идолопоклонством. В римских обрядах также было принято приносить в жертву свинью в церемониях очищения земли. [211] После Третьего еврейского восстания всем евреям под страхом смерти было запрещено входить в город или на прилегающую к нему территорию. [212]

С первого по седьмой век христианство распространилось по всей Римской империи, постепенно став преобладающей религией Палестины, а при византийцах сам Иерусалим был почти полностью христианским, причем большую часть населения составляли христиане-якобиты сирийского обряда . [134] [137]

Император Константин I способствовал христианизации римского общества, отдавая ей приоритет над языческими культами. [213] Одним из последствий этого стало то, что храм Адриана Юпитеру на Храмовой горе был разрушен сразу после Первого Никейского собора в 325 году н. э. по приказу Константина. [214]

Паломник из Бордо , посетивший Иерусалим в 333–334 годах во время правления императора Константина I, писал, что «там есть две статуи Адриана, а недалеко от них — пробитый камень, к которому евреи приходят каждый год и помазывают. Они скорбят и разрывают свои одежды, а затем уходят». [215] Предполагается, что событие произошло в Тиша бе-Ав , поскольку десятилетия спустя Иероним рассказал, что это был единственный день, в который евреям разрешалось входить в Иерусалим. [216]

Племянник Константина император Юлиан в 363 году дал разрешение евреям восстановить Храм. [216] [217] В письме, приписываемом Юлиану, он писал евреям, что «это вы должны сделать, чтобы, когда я успешно закончу войну в Персии, я мог восстановить своими собственными усилиями священный город Иерусалим, который вы так много лет жаждали видеть заселенным, и мог привести туда поселенцев, и вместе с вами мог прославить там Всевышнего Бога». [216] Юлиан считал еврейского Бога достойным членом пантеона богов, в которых он верил, и он также был ярым противником христианства. [216] [218] Церковные историки писали, что евреи начали расчищать строения и обломки на Храмовой горе, но им помешало сначала сильное землетрясение, а затем чудеса, в том числе огонь, возникший из земли. [219] Однако ни один современный еврейский источник не упоминает этот эпизод напрямую. [216]

Во время своих раскопок в 1930-х годах Роберт Гамильтон обнаружил части многоцветного мозаичного пола с геометрическими узорами внутри мечети Аль-Акса, но не опубликовал их. [220] Дата мозаики оспаривается: Захи Двира считает, что они относятся к доисламскому византийскому периоду, в то время как Барух, Райх и Сандхаус отдают предпочтение гораздо более позднему омейядскому происхождению из-за их сходства с известной омейядской мозаикой. [220]

В 610 году империя Сасанидов вытеснила Византийскую империю с Ближнего Востока, впервые за много веков предоставив евреям контроль над Иерусалимом. Евреям в Палестине было разрешено создать вассальное государство под властью империи Сасанидов, названное Сасанидским еврейским содружеством , которое просуществовало пять лет. Еврейские раввины приказали возобновить жертвоприношения животных впервые со времен Второго Храма и начали восстанавливать еврейский Храм. Незадолго до того, как византийцы вернули себе территорию пять лет спустя в 615 году, персы передали контроль христианскому населению, которое снесло частично построенное здание еврейского Храма и превратило его в свалку [221], что и было, когда праведный халиф Умар захватил город в 637 году.

В 637 году арабы осадили и захватили город у Византийской империи, которая победила персидские войска и их союзников и отвоевала город. Нет никаких современных записей, но есть много преданий о происхождении главных исламских зданий на горе. [222] [223] Популярный рассказ из более поздних веков гласит, что праведный халиф Умар был неохотно приведен к этому месту христианским патриархом Софронием . [224] Он нашел его покрытым мусором, но священная Скала была найдена с помощью обращенного еврея Кааба аль-Ахбара . [224] Аль-Ахбар посоветовал Умару построить мечеть к северу от скалы, чтобы верующие были обращены как к скале, так и к Мекке, но вместо этого Умар решил построить ее к югу от скалы. [224] Она стала известна как мечеть аль-Акса. Согласно мусульманским источникам, евреи участвовали в строительстве харама, заложив фундамент для мечетей Аль-Акса и Купол Скалы. [225] Первое известное свидетельство очевидца — это свидетельство паломника Аркульфа , посетившего это место около 670 года. Согласно рассказу Аркульфа, записанному Адомнаном , он видел прямоугольный деревянный молитвенный дом, построенный на руинах, достаточно большой, чтобы вместить 3000 человек. [222] [226]

В 691 году халиф Абд аль-Маликом вокруг скалы было построено восьмиугольное исламское здание, увенчанное куполом, по множеству политических, династических и религиозных причин, построенное на местных и коранических традициях, подчеркивающих святость этого места, процесс, в котором текстовые и архитектурные повествования подкрепляли друг друга. [227] Святилище стало известно как Купол Скалы ( قبة الصخرة , Куббат ас-Сахра ). (Сам купол был покрыт золотом в 1920 году.) В 715 году Омейяды во главе с халифом аль-Валидом I построили мечеть аль-Акса ( المسجد الأقصى , аль-Масджид аль-Акса , букв. «Самая дальняя мечеть»), соответствующая исламскому верованию в чудесное ночное путешествие Мухаммеда , как описано в Коране и хадисах . Термин «Благородное святилище» или «Харам аль-Шариф», как его позже называли мамлюки и османы , относится ко всей области, которая окружает эту скалу. [228]

Период крестоносцев начался в 1099 году с захватом Иерусалима Первым крестовым походом . После завоевания города ордену крестоносцев, известному как тамплиеры, было предоставлено право использовать мечеть Аль-Акса в качестве своей штаб-квартиры. Вероятно, это сделали Балдуин II Иерусалимский и Вармунд, патриарх Иерусалима, на Соборе в Наблусе в январе 1120 года. [229] Храмовая гора имела мистицизм, поскольку она находилась над тем, что, как считалось, было руинами Храма Соломона . [230] [231] Поэтому крестоносцы называли мечеть Аль-Акса Храмом Соломона, и именно по этому месту новый орден получил название «Бедные рыцари Христа и Храма Соломона» или рыцари-«тамплиеры».

В 1187 году, как только он снова захватил Иерусалим, Саладин убрал все следы христианского поклонения с Храмовой горы, вернув Купол Скалы и мечеть Аль-Акса их мусульманским целям. После этого они оставались в руках мусульман, даже в относительно короткие периоды правления крестоносцев после Шестого крестового похода .

На эспланаде Харам и вокруг нее есть несколько зданий мамлюков, например, медресе аль-Ашрафия конца XV века и Сабиль (фонтан) Кайтбея . Мамлюки также подняли уровень Центральной или Тиропейской долины Иерусалима, граничащей с Храмовой горой с запада, построив огромные подземные сооружения, на которых они затем построили крупномасштабные здания. Подземные сооружения и надземные здания периода мамлюков, таким образом, покрывают большую часть западной стены Ирода Храмовой горы.

После османского завоевания Палестины в 1516 году османские власти продолжали политику запрета немусульманам ступать на Храмовую гору до начала XIX века, когда немусульманам снова разрешили посещать это место. [232] [ нужен лучший источник ]

В 1867 году группа Королевских инженеров под руководством лейтенанта Чарльза Уоррена , финансируемая Палестинским исследовательским фондом (PEF), обнаружила ряд туннелей около Храмовой горы. Уоррен тайно [ требуется ссылка ] раскопал несколько туннелей около стен Храмовой горы и был первым, кто задокументировал их нижние ходы. Уоррен также провел некоторые небольшие раскопки внутри Храмовой горы, убрав обломки, которые блокировали проходы, ведущие из камеры Двойных ворот .

Между 1922 и 1924 годами Купол Скалы был восстановлен Исламским Высшим Советом. [233] Сионистское движение в то время решительно выступало против любой идеи о том, что сам Храм может быть восстановлен. Действительно, его вооруженное крыло, милиция Хагана , убило еврея, когда его план взорвать исламские объекты на Хараме привлек их внимание в 1931 году. [234]

Джордан провел две реконструкции Купола Скалы, заменив протекающий деревянный внутренний купол алюминиевым в 1952 году, а когда новый купол дал течь, провел вторую реставрацию между 1959 и 1964 годами. [233]

Ни израильские арабы, ни израильские евреи не могли посещать свои святые места на иорданских территориях в этот период. [235] [236]

7 июня 1967 года во время Шестидневной войны израильские войска продвинулись за линию соглашения о перемирии 1949 года на территории Западного берега , взяв под контроль Старый город Иерусалима , включая Храмовую гору.

Главный раввин Армии обороны Израиля Шломо Горен возглавил солдат на религиозных празднованиях на Храмовой горе и у Стены Плача. Главный раввинат Израиля также объявил религиозный праздник в годовщину, названный « Йом Йерушалаим » (День Иерусалима), который стал национальным праздником в ознаменование воссоединения Иерусалима . Многие считали захват Иерусалима и Храмовой горы чудесным освобождением библейско-мессианского масштаба. [237] Через несколько дней после войны более 200 000 евреев собрались у Стены Плача в первом массовом еврейском паломничестве возле Горы после разрушения Храма в 70 году н. э. Исламские власти не беспокоили Горена, когда он отправился молиться на Гору, пока в Девятый день Ава он не привел 50 последователей и не ввел как шофар , так и переносной ковчег для молитвы, нововведение, которое встревожило власти Вакфа и привело к ухудшению отношений между мусульманскими властями и израильским правительством. [238]

В июне 1969 года австралиец поджег Джамию аль-Аксу . 11 апреля 1982 года еврей спрятался в Куполе Скалы и открыл огонь, убив 2 палестинцев и ранив 44; в 1974, 1977 и 1983 годах группы во главе с Йоэлем Лернером сговорились взорвать и Купол Скалы, и Аль-Аксу. 26 января 1984 года охранники Вакфа обнаружили членов Бней-Йехуда, мессианского культа бывших гангстеров, ставших мистиками, базирующихся в Лифте , пытающихся проникнуть в этот район, чтобы взорвать его. [239] [240] [241]

15 января 1988 года во время Первой интифады израильские войска открыли огонь резиновыми пулями и слезоточивым газом по протестующим возле мечети, ранив 40 верующих. [242] [243]

8 октября 1990 года израильские силы, патрулировавшие это место, не дали верующим добраться до него. Среди верующих женщин был взорван баллончик со слезоточивым газом, что привело к эскалации событий. 12 октября 1990 года палестинские мусульмане яростно протестовали против намерения некоторых экстремистских евреев заложить краеугольный камень на этом месте для Нового Храма в качестве прелюдии к разрушению мусульманских мечетей. Попытка была заблокирована израильскими властями, но широко сообщалось, что демонстранты забрасывали евреев камнями у Стены Плача. [239] [244] По словам палестинского историка Рашида Халиди , журналистские расследования показали, что это утверждение ложно. [245] В конечном итоге были брошены камни, в то время как силы безопасности открыли огонь, в результате которого погибло 21 человек и 150 получили ранения. [239] Израильское расследование установило вину израильских сил, но также пришло к выводу, что обвинения не могут быть предъявлены ни одному конкретному лицу. [246]

8 октября 1990 года 22 палестинца были убиты и более 100 ранены израильской пограничной полицией во время протестов, которые были вызваны объявлением « Верующих Храмовой горы» , группы религиозных евреев, о том, что они собираются заложить краеугольный камень Третьего Храма. [247] [248] В период с 1992 по 1994 год иорданское правительство предприняло беспрецедентный шаг по позолоте купола Купола Скалы, покрыв его 5000 золотыми пластинами, а также восстановив и укрепив конструкцию. Минбар Саладина также был реконструирован. Проект был оплачен лично королем Хусейном , его стоимость составила 8 миллионов долларов. [233] Храмовая гора остается, в соответствии с условиями мирного договора между Израилем и Иорданией 1994 года , под опекой Иордании . [249] В декабре 1997 года израильские службы безопасности предотвратили попытку еврейских экстремистов бросить в этот район голову свиньи, завернутую в страницы Корана, с целью спровоцировать беспорядки и опозорить правительство. [239]

28 сентября 2000 года тогдашний лидер оппозиции Израиля Ариэль Шарон и члены партии Ликуд вместе с 1000 вооруженных охранников посетили комплекс Аль-Акса. Визит был воспринят как провокационный жест многими палестинцами, которые собрались вокруг этого места. После того, как Шарон и члены партии Ликуд ушли, вспыхнула демонстрация, и палестинцы на территории Харам аль-Шарифа начали бросать камни и другие снаряды в израильскую полицию по борьбе с беспорядками. Полиция применила слезоточивый газ и резиновые пули в толпу, ранив 24 человека. Визит спровоцировал пятилетнее восстание палестинцев, обычно называемое интифадой Аль-Акса , хотя некоторые комментаторы, ссылаясь на последующие выступления должностных лиц Палестинской администрации, в частности Имада Фалуджи и Яшара Арафата , утверждают, что интифада была спланирована за несколько месяцев вперед, еще в июле по возвращении Арафата с переговоров в Кэмп-Дэвиде в Соединенных Штатах. [250] [251] [252] 29 сентября израильское правительство направило в мечеть 2000 бойцов полиции по борьбе с беспорядками. Когда группа палестинцев вышла из мечети после пятничной молитвы ( Джумаа ), они стали бросать камни в полицию. Затем полиция ворвалась на территорию мечети, стреляя как боевыми патронами, так и резиновыми пулями в группу палестинцев, убив четырех и ранив около 200 человек. [253]

3 января 2023 года министр национальной безопасности Израиля Итамар Бен-Гвир посетил Храмовую гору в Иерусалиме , что вызвало протесты палестинцев и осуждение ряда арабских стран . [254]

Евреям не разрешалось посещать страну в течение примерно тысячи лет. [ когда? ] [255]

В первые десять лет британского правления в Палестине всем был разрешен вход в комплекс Храмовой горы/Харам аль-Шариф. Иногда на входе между евреями и мусульманами вспыхивали столкновения. Во время беспорядков в Палестине 1929 года евреев обвиняли в нарушении статус-кво. [256] [257] После беспорядков Верховный мусульманский совет и Иерусалимский исламский вакф запретили евреям входить в ворота объекта. В течение мандатного периода еврейские лидеры совершали древние религиозные обряды у Западной стены. Запрет на посещение продолжался до 1948 года [258]

Хотя Соглашение о перемирии 1949 года призывало к «возобновлению нормального функционирования культурных и гуманитарных учреждений на горе Скопус и свободному доступу к ним; свободному доступу к святым местам и культурным учреждениям и использованию кладбища на Масличной горе», на практике реальностью были проволочные и бетонные заграждения. Культурные и религиозные объекты по обе стороны города были разрушены и заброшены, а еврейская община была отстранена от своих святых мест. [259]

Через несколько дней после Шестидневной войны , 17 июня 1967 года, в мечети Аль-Акса состоялась встреча между Моше Даяном и мусульманскими религиозными властями Иерусалима, на которой был пересмотрен статус-кво. [260] Евреям было предоставлено право беспрепятственно и бесплатно посещать Храмовую гору, если они уважали религиозные чувства мусульман и вели себя прилично, но им не разрешалось молиться. Западная стена должна была оставаться местом молитвы евреев. «Религиозный суверенитет» должен был остаться за мусульманами, в то время как «общий суверенитет» стал израильским. [238] Мусульмане возражали против предложения Даяна, поскольку они полностью отвергли израильское завоевание Иерусалима и Храмовой горы. Некоторые евреи во главе с Шломо Гореном , тогдашним главным раввином армии, также возражали, утверждая, что решение передало комплекс мусульманам, поскольку святость Западной стены исходит от горы и символизирует изгнание, в то время как молитва на горе символизирует свободу и возвращение еврейского народа на свою родину. [260] Председатель Верховного суда Аарон Барак в ответ на апелляцию в 1976 году против вмешательства полиции в предполагаемое право человека молиться на этом месте выразил мнение, что, хотя евреи и имели право молиться там, оно не было абсолютным, а подчинялось общественным интересам и правам других групп. Израильские суды сочли этот вопрос выходящим за рамки их компетенции и, учитывая деликатность вопроса, находящимся под политической юрисдикцией. [260] Барак писал:

Основной принцип заключается в том, что каждый еврей имеет право войти на Храмовую гору, молиться там и иметь общение со своим создателем. Это часть религиозной свободы вероисповедания, это часть свободы выражения мнения. Однако, как и в случае с каждым правом человека, это не абсолютное, а относительное право... Действительно, в случае, когда есть почти уверенность, что может быть нанесен ущерб общественным интересам, если права человека на религиозное вероисповедание и свободу выражения мнения будут реализованы, можно ограничить права человека, чтобы поддержать общественные интересы. [238]

Полиция продолжала запрещать евреям молиться на Храмовой горе. [260] Впоследствии несколько премьер-министров также предприняли попытки изменить статус-кво, но потерпели неудачу. В октябре 1986 года соглашение между верующими Храмовой горы , Верховным мусульманским советом и полицией, которое разрешало короткие визиты небольшими группами, было реализовано один раз и больше не повторялось, после того как 2000 мусульман, вооруженных камнями и бутылками, напали на группу и забросали камнями молящихся у Западной стены. В 1990-х годах были предприняты дополнительные попытки провести еврейскую молитву на Храмовой горе, которые были остановлены израильской полицией. [260]

До 2000 года посетители-немусульмане могли войти в Купол Скалы, мечеть Аль-Акса и Исламский музей, получив билет от Вакфа . Эта процедура закончилась, когда разразилась Вторая интифада . Пятнадцать лет спустя переговоры между Израилем и Иорданией могут привести [ нужно обновить ] к повторному открытию этих мест. [261]

В 2010-х годах среди палестинцев возник страх, что Израиль планирует изменить статус-кво и разрешить еврейские молитвы или что мечеть Аль-Акса может быть повреждена или разрушена Израилем. Аль-Акса использовалась как база для нападений на посетителей и полицию, с которой бросали камни, зажигательные бомбы и фейерверки. Израильская полиция ни разу не заходила в мечеть Аль-Акса до 5 ноября 2014 года, когда диалог с лидерами Вакфа и мятежниками провалился. Это привело к введению строгих ограничений на вход посетителей на Храмовую гору. Израильское руководство неоднократно заявляло, что статус-кво не изменится. [262] По словам тогдашнего комиссара полиции Иерусалима Йоханана Данино, это место находится в центре «священной войны», и «любой, кто хочет изменить статус-кво на Храмовой горе, не должен быть допущен туда», ссылаясь на «крайне правую повестку дня по изменению статус-кво на Храмовой горе»; ХАМАС и «Исламский джихад» продолжали ошибочно утверждать, что израильское правительство планировало разрушить мечеть Аль-Акса, что привело к постоянным террористическим атакам и беспорядкам. [263]

Существующее положение вещей претерпело ряд изменений:

Многие палестинцы считают, что статус-кво находится под угрозой, поскольку правые израильтяне бросают ему вызов с большей силой и частотой, утверждая религиозное право молиться там. Пока Израиль не запретил им, члены группы женщин Мурабитат кричали «Аллах Акбар» группам еврейских посетителей, чтобы напомнить им, что Храмовая гора все еще находится в руках мусульман. [264] [265] В октябре 2021 года еврей Арье Липпо, которому израильская полиция запретила посещать Храмовую гору в течение пятнадцати дней после того, как его поймали за тихой молитвой, добился отмены запрета израильским судом на том основании, что его поведение не нарушало инструкции полиции. [266] ХАМАС назвал это решение «явным объявлением войны». [267] Вышестоящий суд Израиля быстро отменил решение нижестоящего суда. [268]

Исламский Вакф непрерывно управлял Храмовой горой с момента мусульманского завоевания Латинского королевства Иерусалим в 1187 году. 7 июня 1967 года, вскоре после того, как Израиль взял под свой контроль этот район во время Шестидневной войны , премьер-министр Леви Эшколь заверил, что «никакого вреда не будет причинено местам, священным для всех религий». Вместе с расширением израильской юрисдикции и управления на восточный Иерусалим Кнессет принял Закон о сохранении святых мест, [269] обеспечивающий защиту святых мест от осквернения, а также свободу доступа к ним. [270] Место остается в пределах территории, контролируемой Государством Израиль , при этом управление местом остается в руках Иерусалимского исламского Вакфа.

Хотя свобода доступа была закреплена в законе, в качестве меры безопасности израильское правительство теперь вводит запрет на молитву немусульман на этом месте. Немусульмане, замеченные молящимися на этом месте, подлежат высылке полицией. [271] В разное время, когда существует опасность арабских беспорядков на горе, приводящих к бросанию камней сверху в сторону площади Западной стены, Израиль не допускал мусульманских мужчин моложе 45 лет молиться на территории комплекса, ссылаясь на эти опасения. [272] Иногда такие ограничения совпадали с пятничными молитвами во время исламского священного месяца Рамадан . [273] Обычно палестинцам Западного берега разрешен доступ в Иерусалим только во время исламских праздников, причем доступ обычно ограничен мужчинами старше 35 лет и женщинами любого возраста, имеющими право на разрешение на въезд в город. [274] Палестинским жителям Иерусалима, которые из-за аннексии Иерусалима Израилем имеют израильские карты постоянного проживания, и израильским арабам разрешен неограниченный доступ на Храмовую гору. [ необходима цитата ] Ворота Муграби — единственный вход на Храмовую гору, доступный для немусульман. [275] [276] [277]

Due to religious restrictions on entering the most sacred areas of the Temple Mount (see following section), the Western Wall, a retaining wall for the Temple Mount and remnant of the Second Temple structure, is considered by some rabbinical authorities to be the holiest accessible site for Jews to pray. A 2013 Knesset committee hearing considered allowing Jews to pray at the site, amidst heated debate. Arab-Israeli MPs were ejected for disrupting the hearing, after shouting at the chairman, calling her a "pyromaniac". Religious Affairs Minister Eli Ben-Dahan of Jewish Home said his ministry was seeking legal ways to enable Jews to pray at the site.[278]

During Temple times, entry to the Mount was limited by a complex set of purity laws. Persons suffering from corpse uncleanness were not allowed to enter the inner court.[279] Non-Jews were also prohibited from entering the inner court of the Temple.[280] A hewn stone measuring 60 cm × 90 cm (24 in × 35 in) and engraved with Greek uncials was discovered in 1871 near a court on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem in which it outlined this prohibition:

ΜΗΟΕΝΑΑΛΛΟΓΕΝΗΕΙΣΠΟ

ΡΕΥΕΣΟΑΙΕΝΤΟΣΤΟΥΠΕ

ΡΙΤΟΙΕΡΟΝΤΡΥΦΑΚΤΟΥΚΑΙ

ΠΕΡΙΒΟΛΟΥΟΣΔΑΝΛΗ

ΦΘΗΕΑΥΤΩΙΑΙΤΙΟΣΕΣ

ΤΑΙΔΙΑΤΟΕΞΑΚΟΛΟΥ

ΘΕΙΝΘΑΝΑΤΟΝ

Translation: "Let no foreigner enter within the parapet and the partition which surrounds the Temple precincts. Anyone caught [violating] will be held accountable for his ensuing death." Today, the stone is preserved in Istanbul's Museum of Antiquities.

Maimonides wrote that it was only permitted to enter the site to fulfill a religious precept. After the destruction of the Temple there was discussion as to whether the site, bereft of the Temple, still maintained its holiness. Jewish codifiers accepted the opinion of Maimonides who ruled that the holiness of the Temple sanctified the site for eternity and consequently the restrictions on entry to the site remain in force.[232] While secular Jews ascend freely, the question of whether ascending is permitted is a matter of some debate among religious authorities, with a majority holding that it is permitted to ascend to the Temple Mount, but not to step on the site of the inner courtyards of the ancient Temple.[232] The question then becomes whether the site can be ascertained accurately.[232][better source needed]

There is debate over whether reports that Maimonides himself ascended the Mount are reliable.[281] One such report[citation needed] claims that he did so on Thursday, October 21, 1165, during the Crusader period. Some early scholars however, claim that entry onto certain areas of the Mount is permitted. It appears that Radbaz also entered the Mount and advised others how to do this. He permits entry from all the gates into the 135 x 135 cubits of the Women's Courtyard in the east, since the biblical prohibition only applies to the 187 x 135 cubits of the Temple in the west.[282] There are also Christian and Islamic sources which indicate that Jews visited the site,[283] but these visits may have been made under duress.[284]

A few hours after the Temple Mount came under Israeli control during the Six-Day War, a message from the Chief Rabbis of Israel, Isser Yehuda Unterman and Yitzhak Nissim was broadcast, warning that Jews were not permitted to enter the site.[285] This warning was reiterated by the Council of the Chief Rabbinate a few days later, which issued an explanation written by Rabbi Bezalel Jolti (Zolti) that "Since the sanctity of the site has never ended, it is forbidden to enter the Temple Mount until the Temple is built."[285] The signatures of more than 300 prominent rabbis were later obtained.[286]

A major critic of the decision of the Chief Rabbinate was Rabbi Shlomo Goren, the chief rabbi of the IDF.[285] According to General Uzi Narkiss, who led the Israeli force that conquered the Temple Mount, Goren proposed to him that the Dome of the Rock be immediately blown up.[286] After Narkiss refused, Goren unsuccessfully petitioned the government to close off the Mount to Jews and non-Jews alike.[286] Later he established his office on the Mount and conducted a series of demonstrations on the Mount in support of the right of Jewish men to enter there.[285] His behavior displeased the government, which restricted his public actions, censored his writings, and in August prevented him from attending the annual Oral Law Conference at which the question of access to the Mount was debated.[287] Although there was considerable opposition, the conference consensus was to confirm the ban on entry to Jews.[287] The ruling said "We have been warned, since time immemorial [lit. 'for generations and generations'], against entering the entire area of the Temple Mount and have indeed avoided doing so."[286][287] According to Ron Hassner, the ruling "brilliantly" solved the government's problem of avoiding ethnic conflict, since those Jews who most respected rabbinical authority were those most likely to clash with Muslims on the Mount.[287]

Rabbinical consensus in the post-1967 period, held that it is forbidden for Jews to enter any part of the Temple Mount,[288] and in January 2005, a declaration was signed confirming the 1967 decision.[289]

Most Haredi rabbis are of the opinion that the Mount is off limits to Jews and non-Jews alike.[290] Their opinions against entering the Temple Mount are based on the current political climate surrounding the Mount,[291] along with the potential danger of entering the hallowed area of the Temple courtyard and the impossibility of fulfilling the ritual requirement of cleansing oneself with the ashes of a red heifer.[292][293] The boundaries of the areas which are completely forbidden, while having large portions in common, are delineated differently by various rabbinic authorities.

However, there is a growing body of Modern Orthodox and national religious rabbis who encourage visits to certain parts of the Mount, which they believe are permitted according to most medieval rabbinical authorities.[232][better source needed] These rabbis include: Shlomo Goren (former Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel); Chaim David Halevi (former Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv and Yafo); Dov Lior (Rabbi of Kiryat Arba); Yosef Elboim; Yisrael Ariel; She'ar Yashuv Cohen (Chief Rabbi of Haifa); Yuval Sherlo (rosh yeshiva of the hesder yeshiva of Petah Tikva); Meir Kahane. One of them, Shlomo Goren, held that it is possible that Jews are even allowed to enter the heart of the Dome of the Rock in time of war, according to Jewish Law of Conquest.[294] These authorities demand an attitude of veneration on the part of Jews ascending the Temple Mount, ablution in a mikveh prior to the ascent, and the wearing of non-leather shoes.[232][better source needed] Some rabbinic authorities are now of the opinion that it is imperative for Jews to ascend in order to halt the ongoing process of Islamization of the Temple Mount. Maimonides, perhaps the greatest codifier of Jewish Law, wrote in Laws of the Chosen House ch 7 Law 15 "One may bring a dead body in to the (lower sanctified areas of the) Temple Mount and there is no need to say that the ritually impure (from the dead) may enter there, because the dead body itself can enter". One who is ritually impure through direct or in-direct contact of the dead cannot walk in the higher sanctified areas. For those who are visibly Jewish, they have no choice, but to follow a peripheral route[295] as it has become unofficially part of the status quo on the Mount. Many of these recent opinions rely on archaeological evidence.[232][better source needed]

In December 2013, the two Chief Rabbis of Israel, David Lau and Yitzhak Yosef, reiterated the ban on Jews entering the Temple Mount.[296] They wrote, "In light of [those] neglecting [this ruling], we once again warn that nothing has changed and this strict prohibition remains in effect for the entire area [of the Temple Mount]".[296] In November 2014, the Sephardic chief rabbi Yitzhak Yosef reiterated the point of view held by many rabbinic authorities that Jews should not visit the Mount.[249]

On the occasion of an upsurge in Palestinian knifing attacks on Israelis, associated with fears that Israel was changing the status quo on the Mount, the Haredi newspaper Mishpacha ran a notification in Arabic asking, 'their cousins', Palestinians, to stop trying to murder members of their congregation, since they were vehemently opposed to ascending the Mount and consider such visits proscribed by Jewish law.[297]

The large courtyard (sahn)[25] can host more than 400,000 worshippers, making it one of the largest mosques in the world.[23]

The upper platform surrounds the Dome of the Rock, beneath which lies the Well of Souls, originally accessible only by a narrow hole in the Sakhrah, the foundation stone on which the Dome of the Rock site and after which it is named, until the Crusaders dug a new entrance to the cave from the south.[298] The platform is accessible via eight staircases, each of which is topped by a free-standing arcade known in Arabic as the qanatir or mawazin. The arcades were erected in different periods from the 10th to 15th centuries.[299]

There is also a smaller domed building on the upper platform, to the east of the Dome of the Rock, known as the Dome of the Chain (Qubbat al-Sisila in Arabic).[300][301] Its exact origin and purpose is uncertain but historical sources indicate it was built under the reign of Abd al-Malik, the same Umayyad caliph who built the Dome of the Rock.[302] Two other small domes stand to the northwest of the Dome of the Rock. The Dome of the Ascension (Qubbat al-Miraj in Arabic) has an inscription with a date corresponding to 1201 CE.[299][303] It may have been a former Crusader structure, possibly a baptistery, that was repurposed at this time,[303] or it may be a structure that was built after Saladin's capture of the city and reused some Crusader-era materials, including its columns.[304] Per its name, this dome commemorates the spot where, according to some, Muhammad ascended to heaven.[305] The Dome of the Spirits or Dome of the Winds (Qubbat al-Arwah in Arabic) stands a little further north and is dated to the 16th century.[306][299]

.jpg/440px-Jerusalem_Temple_Mount_(43195424811).jpg)

In the southwest corner of the upper platform is a quadrangular structure which includes a portion topped by another dome. It is known as the Dome of Literature (Qubba Nahwiyya in Arabic) and dated to 1208.[299] Standing further east, close to one of the southern entrance arcades, is a stone minbar known as the "Summer Pulpit" or Minbar of Burhan al-Din, used for open-air prayers. It appears to be an older ciborium from the Crusader period, as attested by its sculptural decoration, which was then reused under the Ayyubids. Sometime after 1345, a Mamluk judge named Burhan al-Din (d. 1388) restored it and added a stone staircase, giving it its present form.[307][308]

The lower platform – which constitutes most of the surface of the Temple Mount – has at its southern end al-Aqsa Mosque, which takes up most of the width of the Mount. Gardens take up the eastern and most of the northern side of the platform; the far north of the platform houses an Islamic school.[309]

The lower platform also houses an ablution fountain (known as al-Kas), originally supplied with water via a long narrow aqueduct leading from the so-called Solomon's Pools near Bethlehem, but now supplied from Jerusalem's water mains.

There are several cisterns beneath the lower platform, designed to collect rainwater as a water supply. These have various forms and structures, seemingly built in different periods, ranging from vaulted chambers built in the gap between the bedrock and the platform, to chambers cut into the bedrock itself. Of these, the most notable are (numbering traditionally follows Wilson's scheme[310]):

The retaining walls of the platform contain several gateways, all now blocked. In the eastern wall is the Golden Gate, through which legend states the Jewish Messiah would enter Jerusalem. On the southern face are the Hulda Gates – the triple gate (which has three arches) and the double gate (which has two arches and is partly obscured by a Crusader building); these were the entrance and exit (respectively) to the Temple Mount from Ophel (the oldest part of Jerusalem), and the main access to the Mount for ordinary Jews. In the western face, near the southern corner, is the Barclay's Gate – only half visible due to a building (the "house of Abu Sa'ud") on the northern side. Also in the western face, hidden by later construction but visible via the recent Western Wall Tunnels, and only rediscovered by Warren, is Warren's Gate; the function of these western gates is obscure, but many Jews view Warren's Gate as particularly holy, due to its location due west of the Dome of the Rock. The current location of the Dome of the Rock is considered one of the possible locations where the Holy of Holies was placed; numerous alternative opinions exist, based on study and calculations, such as those of Tuvia Sagiv.

Warren was able to investigate the inside of these gates. Warren's Gate and the Golden Gate simply head toward the centre of the Mount, giving access to the surface by steps.[314] Barclay's Gate is similar, but abruptly turns south as it does so; the reason for this is unknown. The double and triple gates (the Huldah Gates) are more substantial; heading into the Mount for some distance they each finally have steps rising to the surface just north of al-Aqsa Mosque.[315] The passageway for each is vaulted, and has two aisles (in the case of the triple gate, a third aisle exists for a brief distance beyond the gate); the eastern aisle of the double gates and western aisle of the triple gates reach the surface, the other aisles terminating some way before the steps. Warren believed that one aisle of each original passage was extended when al-Aqsa Mosque blocked the original surface exits.

In the process of investigating Cistern 10, Warren discovered tunnels that lay under the Triple Gate passageway.[316] These passages lead in erratic directions, some leading beyond the southern edge of the Temple Mount (they are at a depth below the base of the walls); their purpose is unknown – as is whether they predate the Temple Mount – a situation not helped by the fact that apart from Warren's expedition no one else is known to have visited them.

Altogether, there are six major sealed gates and a postern, listed here counterclockwise, dating from either the Roman/Herodian, Byzantine, or Early Muslim periods:

There are now eleven open gates offering access to the Muslim Haram al-Sharif.

Two twin gates follow south of the Ablution Gate, the Tranquility Gate and the Gate of the Chain:

A twelfth gate still open during Ottoman rule is now closed to the public:

East of and joined to the triple gate passageway is a large vaulted area, supporting the southeastern corner of the Temple Mount platform – which is substantially above the bedrock at this point – the vaulted chambers here are popularly referred to as Solomon's Stables.[317] They were used as stables by the Crusaders, but were built by Herod the Great – along with the platform they were built to support.

The complex is bordered on the south and east by the outer walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. On the north and west it is bordered by two long porticos (riwaq), built during the Mamluk period.[318] A number of other structures were also built along these areas, mainly also from the Mamluk period. On the north side, they include the Isardiyya Madrasa, built before 1345, and the Almalikiyya Madrasa, dated to 1340.[319] On the west side, they include the Ashrafiyya Madrasa, built by Sultan Qaytbay between 1480 and 1482,[320] and the adjacent Uthmaniyya Madrasa, dated to 1437.[321] The Sabil of Qaytbay, contemporary with the Ashrafiyya Madrasa, also stands nearby.[320]

The existing four minarets include three along the western perimeter of the esplanade and one along the northern wall. The earliest dated minaret was constructed on the northwest corner of the Temple Mount in 1298, with three other minarets added over the course of the 14th century.[322][323]

Due to the extreme political sensitivity of the site, no real archaeological excavations have ever been conducted on the Temple Mount itself. Protests commonly occur whenever archaeologists conduct projects near the Mount. This sensitivity has not, however, protected both Jewish and Muslim works from accusations of destroying archeological evidence on a number of occasions.[324][325][326] Aside from visual observation of surface features, most other archaeological knowledge of the site comes from the 19th-century survey carried out by Charles Wilson and Charles Warren and others. Since the Waqf is granted almost full autonomy on the Islamic holy sites, Israeli archaeologists have been prevented from inspecting the area, and are restricted to conducting excavations around the Temple Mount.