Рабство — это владение человеком как собственностью , особенно в отношении его труда. [1] Рабство обычно подразумевает принудительную работу, при этом место работы и проживания раба диктуется стороной, которая держит его в рабстве. Порабощение — это помещение человека в рабство, и человек называется рабом или порабощенным человеком (см. § Терминология).

Многие исторические случаи рабства произошли в результате нарушения закона, обременения долгами, военного поражения или эксплуатации для получения более дешевой рабочей силы; другие формы рабства были установлены по демографическим признакам, таким как раса или пол . Рабы могут содержаться в рабстве всю жизнь или в течение фиксированного периода времени, после которого им будет предоставлена свобода . [2] Хотя рабство обычно является недобровольным и подразумевает принуждение, есть также случаи, когда люди добровольно вступают в рабство , чтобы выплатить долг или заработать деньги из-за бедности . В ходе человеческой истории рабство было типичной чертой цивилизации , [3] и было законным в большинстве обществ, но теперь оно запрещено законом в большинстве стран мира, за исключением наказания за преступление . [4] [5]

В рабстве движимого имущества раб юридически становится личной собственностью (движимым имуществом) рабовладельца. В экономике термин рабство де-факто описывает условия несвободного труда и принудительного труда , которые терпит большинство рабов. [6]

Мавритания была последней страной в мире, официально запретившей рабство в 1981 году [7] , а судебное преследование рабовладельцев было установлено в 2007 году. [8] Однако в 2019 году около 40 миллионов человек, из которых 26% были детьми, по-прежнему находились в рабстве во всем мире, несмотря на то, что рабство было незаконным. В современном мире более 50% рабов обеспечивают принудительный труд , как правило, на фабриках и в потогонных цехах частного сектора экономики страны. [9] В промышленно развитых странах торговля людьми является современной разновидностью рабства; в неиндустриальных странах долговая кабала является распространенной формой порабощения, [6] например, пленная домашняя прислуга , люди в принудительных браках и дети-солдаты . [10]

Слово «раб» было заимствовано в среднеанглийский язык через старофранцузское слово esclave , которое в конечном итоге происходит от византийского греческого σκλάβος ( sklábos ) или εσκλαβήνος ( ésklabḗnos ).

Согласно распространённому мнению, известному с XVIII века, византийское Σκλάβινοι ( Sklábinoi ), Έσκλαβηνοί ( Ésklabēnoí ), заимствованное от самоназвания славянского племени *Slověne, в VIII/IX веке превратилось в σκλάβος , εσκλαβήνος ( позднелатинское sclāvus) в значении «военнопленный раб», «раб», поскольку они часто попадали в плен и обращались в рабство. [11] [12] [13] [14] Однако эта версия оспаривается с XIX века. [15] [16]

Альтернативная современная гипотеза утверждает, что средневековое латинское sclāvus через * scylāvus происходит от византийского σκυλάω ( skūláō , skyláō ) или σκυλεύω ( skūleúō , skyleúō ) со значением «раздеть врага (убитого в битве)» или «захватить добычу / извлечь военные трофеи». [17] [18] [19] [20] Эта версия также подверглась критике. [21]

Среди историков ведутся споры о том, следует ли использовать такие термины, как « несвободный рабочий » или «раб», а не «раб», при описании жертв рабства. По мнению тех, кто предлагает изменить терминологию, раб увековечивает преступление рабства в языке, сводя его жертв к нечеловеческому существительному вместо того, чтобы «нести их вперед как людей, а не как собственность, которой они были» (см. также People-first language ). Другие историки предпочитают раба , потому что этот термин знаком и короче, или потому что он точно отражает бесчеловечность рабства, при этом человек подразумевает определенную степень автономии, которую рабство не допускает. [22]

Как социальный институт, рабство движимого имущества классифицирует рабов как движимое имущество ( личную собственность ), принадлежащее поработителю; как и скот, их можно покупать и продавать по своему усмотрению. [23] Исторически рабство движимого имущества было обычной формой рабства и практиковалось в таких местах, как Римская империя и классическая Греция , где оно считалось краеугольным камнем общества. [24] [25] [26] Другие места, где оно широко практиковалось, включают Средневековый Египет , [27] Субсахарскую Африку, [ где? ] [ когда? ] [28] Бразилию, [ когда? ] Соединенные Штаты [ когда? ] и части Карибского бассейна, такие как Куба и Гаити. [ когда? ] [29] [30] Ирокезы порабощали других способами, которые «очень напоминали рабство движимого имущества». [31]

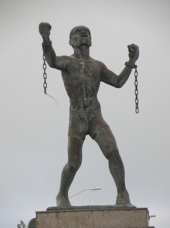

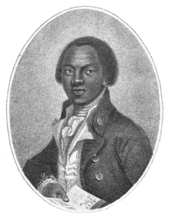

Начиная с XVIII века, ряд аболиционистских движений рассматривали рабство как нарушение прав рабов как людей (« все люди созданы равными ») и стремились отменить его. Аболиционизм столкнулся с огромным сопротивлением, но в конечном итоге добился успеха. Несколько штатов Соединенных Штатов начали отменять рабство во время Американской войны за независимость. Французская революция попыталась отменить рабство в 1794 году, но постоянная отмена произошла только в 1848 году. На большей части территории Британской империи рабство подлежало отмене в 1833 году, на всей территории Соединенных Штатов оно было отменено в 1865 году, а на Кубе — в 1886 году. Последней страной в Америке, отменившей рабство, была Бразилия в 1888 году . [32]

Рабство движимого имущества дольше всего сохранялось на Ближнем Востоке . После того, как трансатлантическая работорговля была подавлена, древняя транссахарская работорговля , работорговля в Индийском океане и работорговля в Красном море продолжали перевозить рабов с африканского континента на Ближний Восток. В течение 20-го века проблема рабства движимого имущества рассматривалась и исследовалась во всем мире международными органами, созданными Лигой Наций и Организацией Объединенных Наций, такими как Временная комиссия по рабству в 1924–1926 годах, Комитет экспертов по рабству в 1932 году и Консультативный комитет экспертов по рабству в 1934–1939 годах. [33] Ко времени Специального комитета ООН по рабству в 1950–1951 годах законное рабство движимого имущества все еще существовало только на Аравийском полуострове: в Омане , Катаре , Саудовской Аравии , в Договорных государствах и в Йемене . [33] Законное рабство было окончательно отменено на Аравийском полуострове в 1960-х годах: в Саудовской Аравии и Йемене в 1962 году, в Дубае в 1963 году и, наконец, в Омане в 1970 году. [33]

Последняя страна, отменившая рабство, Мавритания , сделала это в 1981 году . Запрет на рабство 1981 года не был реализован на практике, поскольку не существовало никаких правовых механизмов для преследования тех, кто использовал рабов, они появились только в 2007 году . [7] [34]

Indenture, также известный как кабальный труд или долговая кабала, является формой несвободного труда, при котором человек работает, чтобы выплатить долг, предоставляя себя в качестве залога. Услуги, требуемые для погашения долга, и их продолжительность могут быть неопределенными. Долговая кабала может передаваться из поколения в поколение, при этом дети должны выплачивать долги своих предков. [35] Это самая распространенная форма рабства на сегодняшний день. [36] Долговая кабала наиболее распространена в Южной Азии. [35] Денежный брак относится к браку, при котором девушку, как правило, выдают замуж за мужчину, чтобы погасить долги ее родителей. [37] Система Chukri — это система долговой кабалы , распространенная в некоторых частях Бенгалии , где женщину могут заставить заниматься проституцией , чтобы выплатить долги. [38]

Слово «рабство» также использовалось для обозначения законного состояния зависимости от кого-либо. [39] [40] Например, в Персии положение и жизнь таких рабов могли быть лучше, чем у обычных граждан. [41]

Принудительный труд, или несвободный труд, иногда используется для описания человека, который вынужден работать против своей воли, под угрозой насилия или другого наказания. Это может также включать институты, которые обычно не классифицируются как рабство, такие как крепостное право , воинская повинность и каторжные работы . Поскольку рабство было юридически запрещено во всех странах, принудительный труд в настоящее время (часто называемый « современным рабством ») вращается вокруг незаконного контроля.

Торговля людьми в основном касается женщин и детей, принуждаемых к проституции , и является самой быстрорастущей формой принудительного труда, при этом Таиланд, Камбоджа, Индия, Бразилия и Мексика были определены как ведущие очаги коммерческой сексуальной эксплуатации детей . [42] [43]

В 2007 году организация Human Rights Watch подсчитала, что от 200 000 до 300 000 детей служили солдатами в текущих конфликтах. [44] Больше девочек в возрасте до 16 лет работают в качестве домашней прислуги, чем любая другая категория детского труда, часто их отправляют в города родители, живущие в сельской бедности, как в случае с гаитянскими реставеками . [45]

Принудительные браки или ранние браки часто считаются видами рабства. Принудительные браки продолжают практиковаться в некоторых частях мира, включая некоторые части Азии и Африки, а также в иммигрантских общинах на Западе. [46] [47] [48] [49] Брак путем похищения происходит во многих местах в мире сегодня, при этом исследование 2003 года показало, что в среднем по стране 69% браков в Эфиопии заключаются путем похищения. [50]

Слово рабство часто используется как уничижительное для описания любой деятельности, в которой человек принуждается к выполнению. Некоторые утверждают, что военные призывы и другие формы принудительного государственного труда представляют собой «государственное рабство». [51] [52] Некоторые либертарианцы и анархо-капиталисты рассматривают государственное налогообложение как форму рабства. [53]

«Рабство» использовалось некоторыми сторонниками антипсихиатрии для определения недобровольных психиатрических пациентов, утверждая, что не существует беспристрастных физических тестов на психическое заболевание, и тем не менее психиатрический пациент должен следовать приказам психиатра. Они утверждают, что вместо цепей для контроля над рабом психиатр использует наркотики для контроля над разумом. [54] Драпетомания была псевдонаучным психиатрическим диагнозом для раба, который желал свободы; «симптомы» включали лень и тенденцию к бегству из плена. [55] [56]

Некоторые сторонники прав животных применяют термин «рабство» к состоянию некоторых или всех животных, принадлежащих человеку, утверждая, что их статус сопоставим со статусом людей-рабов. [57]

Рынок труда, институционализированный в современных капиталистических системах, подвергался критике со стороны основных социалистов и анархо-синдикалистов , которые использовали термин «рабство по найму» как уничижительное или дисфемическое обозначение наемного труда . [58] [59] [60] Социалисты проводят параллели между торговлей рабочей силой как товаром и рабством. Известно, что Цицерон также предлагал такие параллели. [61]

Экономисты смоделировали обстоятельства, при которых рабство (и его разновидности, такие как крепостное право ) появляется и исчезает. Одна из теоретических моделей заключается в том, что рабство становится более желанным для землевладельцев там, где земли много, но рабочей силы мало, так что арендная плата снижается, а наемные рабочие могут требовать высокую заработную плату. Если верно обратное, то землевладельцам дороже охранять рабов, чем нанимать наемных рабочих, которые могут требовать только низкую заработную плату из-за степени конкуренции. [62] Таким образом, сначала рабство, а затем крепостное право постепенно уменьшались в Европе по мере роста населения. Они были вновь введены в Америке и в России, когда стали доступны большие площади земли с небольшим количеством жителей. [63]

Рабство более распространено, когда задачи относительно просты и, следовательно, легко поддаются контролю, например, крупномасштабные монокультуры , такие как сахарный тростник и хлопок , в которых выпуск зависит от экономии масштаба . Это позволяет системам труда, таким как система бригад в Соединенных Штатах, стать заметными на крупных плантациях, где полевые рабочие трудились с фабричной точностью. Затем каждая рабочая бригада была основана на внутреннем разделении труда, которое назначало каждого члена бригады на определенную задачу и делало производительность каждого рабочего зависимой от действий других. Рабы вырубали сорняки, окружавшие растения хлопка, а также лишние ростки. Плужные бригады следовали сзади, перемешивая почву около растений и разбрасывая ее вокруг растений. Таким образом, система бригад работала как сборочная линия . [64]

Начиная с XVIII века критики утверждали, что рабство препятствует технологическому прогрессу, поскольку фокусируется на увеличении числа рабов, выполняющих простые задачи, а не на повышении их эффективности. Например, иногда утверждается, что из-за этой узкой направленности технологии в Греции — а позже и в Риме — не применялись для облегчения физического труда или улучшения производства. [65] [66]

Шотландский экономист Адам Смит утверждал, что свободный труд экономически лучше рабского труда, и что было почти невозможно положить конец рабству в свободной, демократической или республиканской форме правления, поскольку многие из ее законодателей или политических деятелей были рабовладельцами и не наказывали бы себя. Он также утверждал, что рабы могли бы лучше обрести свободу при централизованном правительстве или центральной власти, такой как король или церковь. [67] [68] Подобные аргументы появились позже в работах Огюста Конта , особенно учитывая веру Смита в разделение властей , или то, что Конт называл «разделением духовного и временного» в Средние века и конец рабства, а также критику Смитом хозяев, прошлых и настоящих. Как Смит утверждал в « Лекциях по юриспруденции» : «Огромная власть духовенства, таким образом, совпадающая с властью короля, дала рабам свободу. Но было абсолютно необходимо, чтобы и власть короля, и власть духовенства были велики. Там, где чего-либо из этого не хватало, рабство все еще продолжалось...» [69]

Даже после того, как рабство стало уголовным преступлением, рабовладельцы могли получать высокую прибыль. По словам исследователя Сиддхарта Кары , прибыль, полученная во всем мире от всех форм рабства в 2007 году, составила 91,2 миллиарда долларов. Это уступало только торговле наркотиками с точки зрения глобальных преступных предприятий. В то время средневзвешенная мировая цена продажи раба оценивалась примерно в 340 долларов, с максимумом в 1895 долларов для средней цены проданного секс-раба и минимумом в 40-50 долларов для рабов, находящихся в долговой зависимости в части Азии и Африки. Средневзвешенная годовая прибыль, полученная от раба в 2007 году, составила 3175 долларов, с минимумом в 950 долларов для подневольного труда и 29 210 долларов для проданного секс-раба. Примерно 40% прибыли от рабства каждый год приносили проданные секс-рабыни, что составляет чуть более 4% от 29 миллионов рабов в мире. [70]

_-_men_and_women_eminent_in_the_evolution_of_the_American_of_African_descent_(1914)_(14597416438).jpg/440px-The_Negro_in_American_history_(microform)_-_men_and_women_eminent_in_the_evolution_of_the_American_of_African_descent_(1914)_(14597416438).jpg)

Широко распространенной практикой было клеймение , которое либо явно указывало на то, что рабы являются собственностью, либо служило наказанием.

Рабы находились в частной собственности отдельных лиц, но также находились в государственной собственности. Например, кисэн были женщинами из низших каст в досовременной Корее, которые принадлежали государству под руководством правительственных чиновников, известных как ходжан , и были обязаны развлекать аристократию. В 2020-х годах в Северной Корее Киппумджо ( «Бригады удовольствий») состоят из женщин, выбранных из общего населения, чтобы служить артистками и наложницами правителей Северной Кореи. [71] [72] «Труд дани» — это обязательный труд для государства, который использовался в различных итерациях, таких как барщина , мит'а и репартимьенто . Лагеря для интернированных тоталитарных режимов, таких как нацисты и Советский Союз, придавали все большее значение труду, предоставляемому в этих лагерях, что привело к растущей тенденции среди историков обозначать такие системы как рабство. [73]

Сочетание этих методов включает энкомьенду , когда испанская корона предоставляла частным лицам право на бесплатный труд определенного числа туземцев в определенной области. [74] В «системе красного каучука» как Свободного государства Конго , так и находившегося под управлением Франции Убанги-Шари [75] труд требовался в качестве налогообложения; частным компаниям предоставлялись территории, в пределах которых им разрешалось использовать любые меры для увеличения производства каучука. [ 76] Аренда заключенных была распространена на юге Соединенных Штатов, где государство сдавало заключенных в аренду компаниям для их бесплатного труда.

В зависимости от эпохи и страны рабы иногда имели ограниченный набор юридических прав. Например, в провинции Нью-Йорк люди, которые преднамеренно убивали рабов, подлежали наказанию в соответствии со статутом 1686 года. [77] И, как уже упоминалось, определенные юридические права, закрепленные за ноби в Корее, рабами в различных африканских обществах и чернокожими рабынями во французской колонии Луизиана . Предоставление рабам юридических прав иногда было вопросом морали, но иногда и вопросом личной заинтересованности. Например, в древних Афинах защита рабов от плохого обращения одновременно защищала людей, которых могли принять за рабов, а предоставление рабам ограниченных имущественных прав стимулировало рабов работать усерднее, чтобы получить больше собственности. [78] На юге Соединенных Штатов до отмены рабства в 1865 году в правовом трактате в поддержку рабства сообщалось, что рабы, обвиняемые в преступлениях, как правило, имели законное право на адвоката, свободу от двойной ответственности , право на суд присяжных в более серьезных случаях и право на обвинительное заключение большого жюри, но у них не было многих других прав, таких как способность взрослых белых людей контролировать свою собственную жизнь. [79]

Рабство существовало еще до появления письменных источников и существовало во многих культурах. [3] Рабство редко встречается среди охотников-собирателей , поскольку для него требуются экономические излишки и значительная плотность населения. Таким образом, хотя оно и существовало среди необычайно богатых ресурсами охотников-собирателей, таких как американские индейцы , населяющие богатые лососем реки Тихоокеанского северо-западного побережья, рабство стало широко распространенным только с изобретением сельского хозяйства во время неолитической революции около 11 000 лет назад. [80] Рабство практиковалось почти в каждой древней цивилизации. [3] Такие институты включали долговую кабалу, наказание за преступления, порабощение военнопленных , отказ от детей и порабощение потомков рабов. [81]

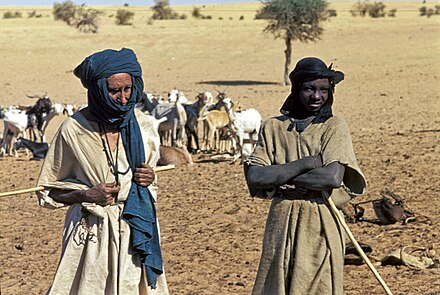

Рабство было широко распространено в Африке, где работорговля велась как внутри страны, так и за ее пределами. [82] В регионе Сенегамбия между 1300 и 1900 годами около трети населения было порабощено. В ранних исламских государствах западного Сахеля , включая Гану , Мали , Сегу и Сонгай , около трети населения были порабощены. [83]

В европейском придворном обществе и европейской аристократии чернокожие африканские рабы и их дети стали заметны в конце 1300-х и 1400-х годах. Начиная с Фридриха II, императора Священной Римской империи , чернокожие африканцы были включены в свиту . В 1402 году эфиопское посольство достигло Венеции . В 1470-х годах чернокожие африканцы были изображены в качестве придворных на настенных росписях, которые были выставлены в Мантуе и Ферраре . В 1490-х годах чернокожие африканцы были включены в эмблему герцога Миланского . [84]

Во время транссахарской работорговли рабы из Западной Африки перевозились через пустыню Сахара в Северную Африку для продажи средиземноморским и ближневосточным цивилизациям. Во время работорговли на Красном море рабы перевозились из Африки через Красное море на Аравийский полуостров. Индийская работорговля , иногда известная как восточноафриканская работорговля, была многонаправленной. Африканцев отправляли в качестве рабов на Аравийский полуостров , на острова Индийского океана (включая Мадагаскар ), на Индийский субконтинент , а позже в Америку. Эти торговцы захватывали народы банту ( зандж ) из внутренних районов современной Кении , Мозамбика и Танзании и привозили их на побережье. [86] [87] Там рабы постепенно ассимилировались в сельских районах, особенно на островах Унгуджа и Пемба . [88]

Некоторые историки утверждают, что около 17 миллионов человек были проданы в рабство на побережье Индийского океана, на Ближнем Востоке и в Северной Африке, и около 5 миллионов африканских рабов были куплены мусульманскими работорговцами и вывезены из Африки через Красное море, Индийский океан и пустыню Сахара между 1500 и 1900 годами . [89] Пленников продавали по всему Ближнему Востоку. Эта торговля ускорилась, поскольку более совершенные суда привели к большему объему торговли и большему спросу на рабочую силу на плантациях в регионе. В конечном итоге, десятки тысяч пленников брались каждый год. [88] [90] [91] Работорговля в Индийском океане была многонаправленной и со временем менялась. Чтобы удовлетворить спрос на черную рабочую силу, рабы банту, купленные восточноафриканскими работорговцами из юго-восточной Африки, продавались в кумулятивно больших количествах на протяжении веков клиентам в Египте, Аравии, Персидском заливе, Индии, европейских колониях на Дальнем Востоке, островах Индийского океана , Эфиопии и Сомали. [92]

Согласно Энциклопедии африканской истории , «предположительно, к 1890-м годам самое большое рабское население мира, около 2 миллионов человек, было сосредоточено на территориях халифата Сокото . Использование рабского труда было обширным, особенно в сельском хозяйстве». [93] [94] Общество по борьбе с рабством подсчитало, что в начале 1930-х годов в Эфиопии было 2 миллиона рабов из предполагаемого населения в 8-16 миллионов. [95]

Рабский труд в Восточной Африке был взят из зинджей , народов банту, которые жили вдоль восточноафриканского побережья. [87] [96] Зенджей на протяжении столетий отправлялись в качестве рабов арабскими торговцами во все страны, граничащие с Индийским океаном, во время работорговли в Индийском океане . Омейядские и Аббасидские халифы набирали множество рабов-зинджей в качестве солдат, и уже в 696 году произошли восстания рабов-зинджей против своих арабских поработителей во время их рабства в Омейядском халифате в Ираке. Считается, что в восстании зинджей , серии восстаний, которые произошли между 869 и 883 годами около Басры (также известной как Басара), против рабства в Аббасидском халифате, расположенном на территории современного Ирака, участвовали порабощенные зинджей, которые первоначально были захвачены из региона Великих африканских озер и районов южнее Восточной Африки . [97] В конфликте приняли участие более 500 000 рабов и свободных людей, привезенных со всей мусульманской империи , и он унес более «десятков тысяч жизней в нижнем Ираке». [98]

Зенджи, которых увозили в качестве рабов на Ближний Восток, часто использовались на тяжелых сельскохозяйственных работах. [99] По мере того, как плантационная экономика процветала, а арабы богатели, сельское хозяйство и другие виды ручного труда считались унизительными. Возникшая в результате нехватка рабочей силы привела к росту рынка рабов.

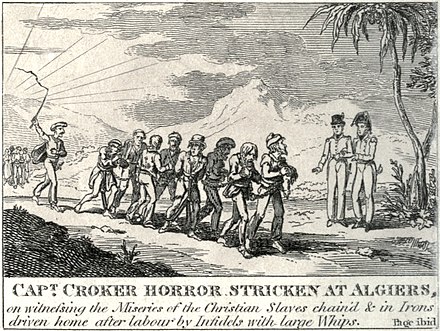

В Алжире , столице Алжира, захваченные христиане и европейцы были обращены в рабство. Примерно в 1650 году в Алжире насчитывалось около 35 000 христианских рабов. [100] По одной из оценок, набеги берберийских работорговцев на прибрежные деревни и корабли, простирающиеся от Италии до Исландии, привели к порабощению примерно от 1 до 1,25 миллиона европейцев между 16 и 19 веками. [101] [102] [103] Однако эта оценка является результатом экстраполяции, которая предполагает, что число европейских рабов, захваченных берберийскими пиратами, было постоянным в течение 250-летнего периода:

Нет никаких записей о том, сколько мужчин, женщин и детей были порабощены, но можно приблизительно подсчитать количество новых пленников, которые были бы необходимы для поддержания населения стабильным и замены тех рабов, которые умерли, сбежали, были выкуплены или обращены в ислам. На этой основе считается, что около 8500 новых рабов требовалось ежегодно для пополнения численности — около 850 000 пленников за столетие с 1580 по 1680 год. В более широком смысле, за 250 лет между 1530 и 1780 годами эта цифра могла легко достигать 1 250 000. [104]

Цифры Дэвиса были опровергнуты другими историками, такими как Дэвид Эрл, который предупреждает, что истинная картина европейских рабов омрачена тем фактом, что корсары также захватывали нехристианских белых из Восточной Европы. [104] Кроме того, количество проданных рабов было гиперактивным, [ необходимо разъяснение ] с преувеличенными оценками, основанными на пиковых годах для расчета средних значений за целые столетия или тысячелетия. Следовательно, были большие колебания из года в год, особенно в 18 и 19 веках, учитывая импорт рабов, а также тот факт, что до 1840-х годов не было последовательных записей. Эксперт по Ближнему Востоку Джон Райт предупреждает, что современные оценки основаны на обратных расчетах из человеческих наблюдений. [105] Такие наблюдения, сделанные наблюдателями конца XVI и начала XVII века, насчитывают около 35 000 европейских христианских рабов, содержавшихся в течение этого периода на Берберийском побережье, в Триполи, Тунисе, но в основном в Алжире. Большинство из них были моряками (особенно те, кто был англичанами), взятыми на своих кораблях, но другие были рыбаками и жителями прибрежных деревень. Однако большинство этих пленников были выходцами из земель, близких к Африке, в частности из Испании и Италии. [34] Это в конечном итоге привело к бомбардировке Алжира англо-голландским флотом в 1816 году. [106] [107]

При оманских арабах Занзибар стал главным рабским портом Восточной Африки , через который в течение 19 века ежегодно проходило до 50 000 африканских рабов. [108] [109] Некоторые историки подсчитали, что от 11 до 18 миллионов африканских рабов пересекли Красное море, Индийский океан и пустыню Сахара с 650 по 1900 год нашей эры. [3] [ проверка не удалась ] [110] Эдуард Рюппель описал потери суданских рабов, которых переправляли пешком в Египет: «после кампании Дафтардар-бея 1822 года в южных горах Нубии было захвачено около 40 000 рабов. Однако из-за плохого обращения, болезней и путешествий по пустыне едва ли 5 000 добрались до Египта». [111] WA Veenhoven писал: «Немецкий врач Густав Нахтигаль , очевидец, считал, что на каждого раба, прибывшего на рынок, трое или четверо умирали по дороге... Келти ( The Partition of Africa , Лондон, 1920) считает, что на каждого раба, привезенного арабами на побережье, по крайней мере шестеро умирали по дороге или во время набега работорговцев. Ливингстон оценивает эту цифру как десять к одному». [112]

Системы подневольного состояния и рабства были распространены в некоторых частях Африки, как и во многих частях древнего мира . Во многих африканских обществах, где рабство было распространено, рабы не рассматривались как движимое имущество и им предоставлялись определенные права в системе, похожей на кабальное рабство в других частях мира. Формы рабства в Африке были тесно связаны со структурами родства . Во многих африканских общинах, где земля не могла принадлежать, порабощение людей использовалось как средство увеличения влияния человека и расширения связей. [113] Это делало рабов постоянной частью родословной хозяина, а дети рабов могли стать тесно связанными с более крупными семейными узами. [114] Дети рабов, рожденные в семьях, могли быть интегрированы в родственную группу хозяина и занять видные позиции в обществе, даже до уровня вождя в некоторых случаях. Однако стигма часто оставалась прикрепленной, и могло быть строгое разделение между рабами-членами родственной группы и теми, кто был связан с хозяином. [113] Рабство практиковалось во многих различных формах: долговое рабство, порабощение военнопленных, военное рабство и уголовное рабство практиковались в различных частях Африки. [115] Рабство для бытовых и судебных целей было широко распространено по всей Африке.

.jpg/440px-Kenneth_Lu_-_Slave_ship_model_(_(4811223749).jpg)

Когда началась атлантическая работорговля , многие местные работорговцы начали поставлять пленников на рынки рабов за пределами Африки. Хотя атлантическая работорговля была не единственной работорговлей из Африки, она была крупнейшей по объему и интенсивности. Как писала Эликия М'боколо в Le Monde diplomatique :

Африканский континент был обескровлен своими человеческими ресурсами всеми возможными путями. Через Сахару, через Красное море, из портов Индийского океана и через Атлантику. По крайней мере десять столетий рабства на благо мусульманских стран (с девятого по девятнадцатый век)... Четыре миллиона рабов были вывезены через Красное море , еще четыре миллиона через суахилийские порты Индийского океана, возможно, целых девять миллионов по транссахарскому караванному пути и от одиннадцати до двадцати миллионов (в зависимости от автора) через Атлантический океан. [116]

Трансатлантическая работорговля достигла своего пика в конце XVIII века, когда наибольшее количество рабов было захвачено во время набегов на внутренние районы Западной Африки.

Эти экспедиции обычно осуществлялись африканскими королевствами , такими как Империя Ойо ( Йоруба ), Империя Ашанти , [117] королевство Дагомея , [118] и Конфедерация Аро . [119] По оценкам, около 15 процентов рабов погибли во время плавания , причем уровень смертности был значительно выше в самой Африке в процессе захвата и транспортировки коренных народов на корабли. [120] [121]

Рабство в Мексике можно проследить до ацтеков . [122] Другие индейцы , такие как инки Анд, тупинамба Бразилии, крики Джорджии и команчи Техаса, также практиковали рабство. [3]

Рабство в Канаде практиковалось коренными народами и европейскими поселенцами . [123] Рабовладельцами на территории, которая стала Канадой, были, например, рыболовецкие общества, такие как юроки , которые жили вдоль побережья Тихого океана от Аляски до Калифорнии, [124] на том, что иногда описывается как Тихоокеанское или Северное северо-западное побережье. Некоторые из коренных народов Тихоокеанского северо-западного побережья , такие как хайда и тлинкиты , традиционно были известны как свирепые воины и работорговцы, совершавшие набеги вплоть до Калифорнии. Рабство было наследственным, рабы были военнопленными , а их потомки были рабами. [125] Некоторые народы в Британской Колумбии продолжали сегрегировать и подвергать остракизму потомков рабов вплоть до 1970-х годов. [126]

Рабство в Америке остается спорным вопросом и сыграло важную роль в истории и развитии некоторых стран, вызвав революцию , гражданскую войну и многочисленные восстания.

Странами, которые контролировали большую часть трансатлантического рынка рабов по количеству переправленных рабов, были Великобритания, Португалия и Франция.

Чтобы утвердиться в качестве американской империи, Испании пришлось бороться с относительно могущественными цивилизациями Нового Света . Испанское завоевание коренных народов в Америке включало использование коренных народов в качестве принудительного труда. Испанские колонии были первыми европейцами, которые использовали африканских рабов в Новом Свете на таких островах, как Куба и Эспаньола . [127] Некоторые современные авторы утверждали, что это было по сути безнравственно. [128] [129] [130] Бартоломе де лас Касас , доминиканский монах XVI века и испанский историк, участвовал в кампаниях на Кубе (в Баямо и Камагуэе ) и присутствовал при резне в Атуэе ; его наблюдение за этой резней побудило его бороться за социальное движение против использования коренных народов в качестве рабов. Кроме того, тревожное сокращение численности коренного населения подстегнуло первые королевские законы, защищающие коренное население . Первые африканские рабы прибыли на Эспаньолу в 1501 году. [131] В эту эпоху наблюдался рост рабства по расовому признаку. [132] Англия играла видную роль в атлантической работорговле. « Рабский треугольник » был создан Фрэнсисом Дрейком и его соратниками, хотя английская работорговля не развивалась до середины 17 века.

Многие белые, прибывшие в Северную Америку в XVII и XVIII веках, были заключены контракты в качестве кабальных слуг. [133] Переход от кабального рабства к рабству был постепенным процессом в Вирджинии. Самое раннее юридическое документирование такого перехода относится к 1640 году, когда чернокожий мужчина, Джон Панч , был приговорен к пожизненному рабству, что заставило его служить своему хозяину, Хью Гвину , до конца его жизни за попытку побега. Этот случай был знаменателен, поскольку он установил несоответствие между его приговором как чернокожего мужчины и приговором двух белых кабальных слуг, которые сбежали вместе с ним (один описан как голландец, а другой как шотландец). Это первый задокументированный случай чернокожего мужчины, приговоренного к пожизненному рабству, и считается одним из первых судебных дел, в котором проводится расовое различие между чернокожими и белыми кабальными слугами. [134] [135]

После 1640 года плантаторы начали игнорировать истечение срока действия контрактов и держать своих слуг в качестве рабов на всю жизнь. Это было продемонстрировано в деле 1655 года Джонсон против Паркера , где суд постановил, что чернокожему мужчине, Энтони Джонсону из Вирджинии, было предоставлено право собственности на другого чернокожего мужчину, Джона Касора , в результате гражданского дела. [136] Это был первый случай судебного определения в Тринадцати колониях, постановившего, что человек, не совершивший преступления, может содержаться в рабстве на всю жизнь. [137] [138]

В 1519 году Эрнан Кортес привез в этот район первого современного раба . [139] В середине XVI века испанские Новые Законы запретили рабство коренных народов, включая ацтеков . Это привело к нехватке рабочей силы. Это привело к импорту африканских рабов, так как они не были восприимчивы к оспе. Взамен многим африканцам была предоставлена возможность купить свою свободу, в то время как другим в конечном итоге их хозяева даровали свободу. [139] На Ямайке испанцы поработили многих таино ; некоторые сбежали, но большинство умерло от европейских болезней и переутомления. Испанцы также ввезли первых африканских рабов. [140]

Испания практически не торговала рабами до 1810 года после восстаний и обретения независимости ее американскими территориями или вице-королевствами. После вторжения Наполеона Испания потеряла свою промышленность и свои американские территории, за исключением Кубы и Пуэрто-Рико, где с 1810 года началась массовая торговля африканскими рабами на Кубе. Ее начали французские плантаторы, изгнанные из французской потерянной колонии Сан-Доминго (Гаити), которые обосновались в восточной части Кубы.

В 1789 году испанская корона возглавила попытку реформировать рабство, поскольку спрос на рабский труд на Кубе рос. Корона издала указ, Código Negro Español (Испанский черный кодекс), который определял положения о еде и одежде, устанавливал ограничения на количество рабочих часов , ограничивал наказания, требовал религиозного обучения и защищал браки, запрещая продажу маленьких детей от их матерей. Британцы внесли и другие изменения в институт рабства на Кубе. Однако плантаторы часто пренебрегали законами и протестовали против них, считая их угрозой своей власти и вторжением в свою личную жизнь. [141]

,_plate_III_-_BL.jpg/440px-Slaves_working_on_a_plantation_-_Ten_Views_in_the_Island_of_Antigua_(1823),_plate_III_-_BL.jpg)

В начале 17 века большую часть рабочей силы на Барбадосе обеспечивали европейские кабальные слуги, в основном англичане , ирландцы и шотландцы , а африканские и коренные американские рабы составляли лишь небольшую часть рабочей силы. Введение сахарного тростника в 1640 году полностью преобразило общество и экономику. В конечном итоге на Барбадосе появилась одна из крупнейших в мире сахарных отраслей промышленности. [142] Работоспособная сахарная плантация требовала больших инвестиций и большого количества тяжелого труда. Сначала голландские торговцы поставляли оборудование, финансирование и африканских рабов, а также перевозили большую часть сахара в Европу. В 1644 году население Барбадоса оценивалось в 30 000 человек, из которых около 800 были африканского происхождения, а остальные в основном английского происхождения. К 1700 году насчитывалось 15 000 свободных белых и 50 000 рабов-африканцев. На Ямайке, хотя численность африканских рабов в 1670-х и 1680-х годах никогда не превышала 10 000 человек, к 1800 году она возросла до более чем 300 000 человек. Увеличилось применение рабских кодексов или черных кодексов, которые создали дифференцированное отношение между африканцами и белыми рабочими и правящим классом плантаторов. В ответ на эти кодексы в это время было предпринято или запланировано несколько восстаний рабов, но ни одно из них не увенчалось успехом.

Плантаторы голландской колонии Суринам в значительной степени полагались на африканских рабов для выращивания, сбора и переработки товарных культур кофе, какао, сахарного тростника и хлопковых плантаций. [143] Нидерланды отменили рабство в Суринаме в 1863 году.

Многие рабы сбежали с плантаций. С помощью коренных южноамериканцев, живущих в прилегающих дождевых лесах, эти беглые рабы создали новую и уникальную культуру внутри страны, которая сама по себе была весьма успешной. Они были известны под общим названием на английском языке как Maroons , на французском как Nèg'Marrons (буквально означает «коричневые негры», то есть «бледнокожие негры»), а на голландском как Marrons . Мароны постепенно развили несколько независимых племен через процесс этногенеза , поскольку они состояли из рабов из разных африканских этнических групп. Эти племена включают Saramaka , Paramaka, Ndyuka или Aukan, Kwinti , Aluku или Boni и Matawai. Мароны часто совершали набеги на плантации, чтобы вербовать новых членов из числа рабов и захватывать женщин, а также чтобы заполучить оружие, еду и припасы. Иногда они убивали плантаторов и их семьи во время набегов. [144] Колонисты также организовали вооруженные кампании против маронов, которые обычно спасались бегством через дождевые леса, которые они знали гораздо лучше, чем колонисты. Чтобы положить конец военным действиям, в XVIII веке европейские колониальные власти подписали несколько мирных договоров с разными племенами. Они предоставили маронам суверенный статус и торговые права на их внутренних территориях, дав им автономию.

Рабство в Бразилии началось задолго до того, как в 1532 году было основано первое португальское поселение , поскольку члены одного племени обращали в рабство захваченных членов другого. [145]

Позже, португальские колонисты сильно зависели от труда коренных народов на начальных этапах поселения, чтобы поддерживать натуральное хозяйство, и туземцы часто захватывались экспедициями, называемыми бандейрас . Импорт африканских рабов начался в середине XVI века, но порабощение коренных народов продолжалось вплоть до XVII и XVIII веков.

В эпоху атлантической работорговли Бразилия импортировала больше африканских рабов, чем любая другая страна. Почти 5 миллионов рабов были привезены из Африки в Бразилию в период с 1501 по 1866 год. [146] До начала 1850-х годов большинство африканских рабов, прибывавших на бразильские берега, были вынуждены садиться в портах Западной Центральной Африки, особенно в Луанде (в современной Анголе). Сегодня, за исключением Нигерии, страной с наибольшим населением лиц африканского происхождения является Бразилия. [147]

Рабский труд был движущей силой роста сахарной экономики в Бразилии, а сахар был основным экспортным товаром колонии с 1600 по 1650 год. В 1690 году в Бразилии были обнаружены месторождения золота и алмазов, что вызвало увеличение импорта африканских рабов для обеспечения этого нового прибыльного рынка. Были разработаны транспортные системы для инфраструктуры горнодобывающей промышленности, и население резко возросло за счет иммигрантов, стремящихся принять участие в добыче золота и алмазов. Спрос на африканских рабов не уменьшился после упадка горнодобывающей промышленности во второй половине 18 века. После роста населения распространились скотоводство и производство продуктов питания, оба из которых в значительной степени зависели от рабского труда. 1,7 миллиона рабов были импортированы в Бразилию из Африки с 1700 по 1800 год, а рост производства кофе в 1830-х годах еще больше побудил к расширению работорговли.

Бразилия была последней страной в западном мире, отменившей рабство. Сорок процентов от общего числа рабов, привезенных в Америку, были отправлены в Бразилию. Для справки, Соединенные Штаты получили 10 процентов. Несмотря на отмену, в Бразилии в 21 веке все еще есть люди, работающие в условиях, похожих на рабство.

Рабство на Гаити началось с прибытием на остров Христофора Колумба в 1492 году. Эта практика была разрушительной для коренного населения. [148] После того, как коренное население таино было почти полностью истреблено принудительным трудом, болезнями и войной, испанцы, по совету католического священника Бартоломе де лас Касаса и с благословения католической церкви, которая также желала защитить коренное население, начали серьезно заниматься использованием африканских рабов. [ необходимо разъяснение ] Во время французского колониального периода, начавшегося в 1625 году, экономика Гаити (тогда известного как Сан-Доминго ) была основана на рабстве, и эта практика считалась самой жестокой в мире.

После Рисвикского договора 1697 года Эспаньола была разделена между Францией и Испанией . Франция получила западную треть и впоследствии назвала ее Сан-Доминго. Чтобы превратить ее в плантации сахарного тростника, французы импортировали тысячи рабов из Африки. Сахар был прибыльной товарной культурой на протяжении всего XVIII века. К 1789 году в Сан-Доминго проживало около 40 000 белых колонистов. Белых значительно превосходили по численности десятки тысяч африканских рабов, которых они импортировали для работы на своих плантациях, которые в основном были посвящены производству сахарного тростника. На севере острова рабы смогли сохранить множество связей с африканской культурой, религией и языком; эти связи постоянно возобновлялись вновь привезенными африканцами. Чернокожих было примерно десять к одному.

Французский Code Noir («Черный кодекс»), подготовленный Жаном-Батистом Кольбером и ратифицированный Людовиком XIV , установил правила обращения с рабами и допустимые свободы. Сан-Доминго описывали как одну из самых жестоких и эффективных колоний рабов; треть недавно привезенных африканцев умирали в течение нескольких лет. [149] Многие рабы умирали от таких болезней, как оспа и брюшной тиф . [150] У них был уровень рождаемости около 3 процентов, и есть доказательства того, что некоторые женщины делали аборты или совершали детоубийства , вместо того чтобы позволить своим детям жить в узах рабства. [151] [152]

Как и в колонии Луизиана , французское колониальное правительство предоставило некоторые права свободным цветным людям : потомкам смешанной расы белых мужчин-колонистов и чернокожих женщин-рабынь (а позже и женщин смешанной расы). Со временем многие были освобождены от рабства. Они создали отдельный социальный класс. Белые французские отцы -креолы часто отправляли своих сыновей смешанной расы во Францию для получения образования. Некоторые цветные мужчины были приняты в армию. Больше свободных цветных людей жили на юге острова, недалеко от Порт-о-Пренса , и многие вступали в смешанные браки внутри своей общины. Они часто работали ремесленниками и торговцами и начали владеть некоторой собственностью. Некоторые стали рабовладельцами. Свободные цветные люди обратились в колониальное правительство с петицией о расширении их прав.

Рабы, попавшие на Гаити из трансатлантического путешествия, и рабы, родившиеся на Гаити, были впервые задокументированы в архивах Гаити и переданы в Министерство обороны и Министерство иностранных дел Франции. По состоянию на 2015 год [update]эти записи находятся в Национальном архиве Франции. Согласно переписи 1788 года, население Гаити состояло из почти 40 000 белых, 30 000 свободных цветных и 450 000 рабов. [153]

Гаитянская революция 1804 года, единственное успешное восстание рабов в истории человечества, ускорила отмену рабства во всех французских колониях, которая произошла в 1848 году .

Рабство в Соединенных Штатах было правовым институтом порабощения людей, в первую очередь африканцев и афроамериканцев , которое существовало в Соединенных Штатах Америки в XVIII и XIX веках, после обретения независимости от Британии и до окончания Гражданской войны в США . Рабство практиковалось в Британской Америке с ранних колониальных дней и было законным во всех Тринадцати колониях , во время Декларации независимости в 1776 году. Ко времени Американской революции статус раба был институционализирован как расовая каста, связанная с африканским происхождением. [154] Соединенные Штаты стали поляризованными по вопросу рабства, представленным рабовладельческими и свободными штатами, разделенными линией Мейсона-Диксона , которая отделяла свободную Пенсильванию от рабских Мэриленда и Делавэра.

Конгресс во время администрации Джефферсона запретил импорт рабов , вступивший в силу в 1808 году, хотя контрабанда (незаконный импорт) не была чем-то необычным. [155] Однако внутренняя работорговля продолжалась быстрыми темпами, движимая требованиями рабочей силы от развития хлопковых плантаций на Глубоком Юге . Эти штаты пытались распространить рабство на новые западные территории, чтобы сохранить свою долю политической власти в стране. Такие законы, предложенные Конгрессу для продолжения распространения рабства в недавно ратифицированных штатах, включают Закон Канзас-Небраска .

Обращение с рабами в Соединенных Штатах сильно различалось в зависимости от условий, времени и места. Властные отношения рабства развратили многих белых, которые имели власть над рабами, а дети проявляли собственную жестокость. Хозяева и надсмотрщики прибегали к физическим наказаниям, чтобы навязать свою волю. Рабов наказывали плетью, заковыванием в кандалы, повешением , избиением , сжиганием, увечьем, клеймением и тюремным заключением. Наказание чаще всего назначалось в ответ на непослушание или предполагаемые нарушения, но иногда злоупотребления применялись для подтверждения господства хозяина или надсмотрщика над рабом. [156] Обращение обычно было более суровым на крупных плантациях, которые часто управлялись надсмотрщиками и принадлежали отсутствующим рабовладельцам.

Уильям Уэллс Браун , сбежавший на свободу, сообщил, что на одной плантации рабы-мужчины должны были собирать 80 фунтов (36 кг) хлопка в день, в то время как женщины должны были собирать 70 фунтов (32 кг) в день; если какой-либо раб не выполнял свою квоту, его подвергали ударам плетью за каждый недостающий фунт. Столб для порки стоял рядом с весами для хлопка. [157] Житель Нью-Йорка, посетивший аукцион рабов в середине 19 века, сообщил, что по крайней мере три четверти мужчин-рабов, которых он видел на продаже, имели шрамы на спинах от порки. [158] Напротив, в небольших семьях рабовладельцев были более тесные отношения между хозяевами и рабами; это иногда приводило к более гуманной среде, но не было данностью. [156]

Более миллиона рабов были проданы с Верхнего Юга , где был избыток рабочей силы, и отправлены на Глубокий Юг в принудительном переселении, что разделило многие семьи. Новые общины афроамериканской культуры были созданы на Глубоком Юге, и общее количество рабов на Юге в конечном итоге достигло 4 миллионов до освобождения. [159] [160] В 19 веке сторонники рабства часто защищали этот институт как «необходимое зло». Белые люди того времени опасались, что освобождение черных рабов будет иметь более пагубные социальные и экономические последствия, чем продолжение рабства. Французский писатель и путешественник Алексис де Токвиль в своей книге «Демократия в Америке» (1835) выразил несогласие с рабством, наблюдая его влияние на американское общество. Он считал, что многорасовое общество без рабства было несостоятельным, поскольку он считал, что предубеждения против черных людей возрастали по мере предоставления им больших прав. Другие, как Джеймс Генри Хэммонд, утверждали, что рабство было «позитивным благом», заявляя: «Такой класс должен быть, иначе не было бы того другого класса, который ведет за собой прогресс, цивилизацию и утонченность».

Правительства южных штатов хотели сохранить баланс между числом рабовладельческих и свободных штатов, чтобы сохранить политический баланс сил в Конгрессе . Новые территории, приобретенные у Великобритании , Франции и Мексики, стали предметом крупных политических компромиссов. К 1850 году недавно разбогатевший хлопководческий Юг угрожал выйти из Союза , и напряженность продолжала расти. Многие белые южные христиане, включая церковных служителей, пытались оправдать свою поддержку рабства, измененного христианским патернализмом. [161] Крупнейшие конфессии, баптистская, методистская и пресвитерианская церкви, разделились по вопросу рабства на региональные организации Севера и Юга.

Когда Авраам Линкольн победил на выборах 1860 года на платформе прекращения расширения рабства, согласно переписи населения США 1860 года , примерно 400 000 человек, что составляло 8% всех семей США, владели почти 4 000 000 рабами. [162] Одна треть южных семей владела рабами. [163] Юг был в значительной степени вовлечен в рабство. Таким образом, после избрания Линкольна семь штатов отделились, образовав Конфедеративные Штаты Америки . Первые шесть отделившихся штатов имели наибольшее количество рабов на Юге. Вскоре после этого из-за вопроса рабства в Соединенных Штатах разразилась полномасштабная Гражданская война , и рабство юридически прекратило свое существование как институт после войны в декабре 1865 года.

В 1865 году Соединенные Штаты ратифицировали 13-ю поправку к Конституции Соединенных Штатов , которая запретила рабство и подневольное услужение «за исключением наказания за преступление, за которое лицо было должным образом осуждено», что обеспечило правовую основу для продолжения принудительного труда в стране. Это привело к появлению системы аренды заключенных , которая затронула в первую очередь афроамериканцев. Инициатива тюремной политики , американский аналитический центр по уголовному правосудию, приводит данные о численности тюремного населения США в 2020 году в 2,3 миллиона человек, и почти все трудоспособные заключенные работают в той или иной форме. В Техасе , Джорджии , Алабаме и Арканзасе заключенным вообще не платят за их работу. В других штатах заключенным платят от 0,12 до 1,15 доллара в час. В 2017 году компания Federal Prison Industries платила заключенным в среднем 0,90 доллара в час. Заключенные, которые отказываются работать, могут быть бессрочно заключены в одиночную камеру или лишены возможности видеться с семьей. С 2010 по 2015 год и снова в 2016 и 2018 годах некоторые заключенные в США отказывались работать , протестуя за лучшую оплату, лучшие условия и прекращение принудительного труда. Лидеры забастовки были наказаны бессрочным одиночным заключением. Принудительный труд заключенных происходит как в государственных, так и в частных тюрьмах . CoreCivic и GEO Group составляют половину доли рынка частных тюрем, и в 2015 году они получили совокупный доход в размере 3,5 миллиарда долларов. Стоимость всего труда заключенных в Соединенных Штатах оценивается в миллиарды. В Калифорнии 2500 заключенных боролись с лесными пожарами всего за 1 доллар в час в рамках программы лагеря по охране природы CDCR , которая экономит штату до 100 миллионов долларов в год. [164]

Рабство существовало в Древнем Китае еще во времена династии Шан . [165] Рабство в основном использовалось правительствами как средство поддержания общественной рабочей силы. [166] [167] До династии Хань рабы иногда подвергались дискриминации, но их правовой статус был гарантирован. Как видно из некоторых исторических записей, таких как «У Дуаньшэна, маркиза Шоусян, была конфискована территория , потому что он убил рабыню» ( записи династии Хань в Дунгуане ), « Сын Ван Мана Ван Хо убил раба, Ван Ман сурово критиковал его и заставил покончить жизнь самоубийством» ( Книга Хань : Биография Ван Мана ), Убийство рабов было таким же табу, как и убийство свободных людей, и виновные всегда сурово наказывались. Можно сказать, что династия Хань сильно отличалась от других стран того же периода (в большинстве случаев лорды имели право убивать своих рабов) с точки зрения прав человека в отношении рабов .

После Южной и Северной династий , из-за неурожаев, наплыва иностранных племен и последовавших за этим войн, количество рабов резко возросло. Они стали классом и назывались «цзяньминь» ( китайск . 贱民), что буквально означает «низший человек». Как указано в комментарии к Кодексу Тан : «Рабы и низшие люди юридически эквивалентны продуктам скота », они всегда имели низкий социальный статус, и даже если их преднамеренно убивали, виновные получали только год тюрьмы и наказывались, даже когда сообщали о преступлениях своих господ. [168] Однако в более поздний период династии, возможно, из-за того, что рост числа рабов снова замедлился, наказания за преступления против них снова стали суровыми. Например, известная современная поэтесса Юй Сюаньцзи была публично казнена за убийство собственного раба.

Многие китайцы-ханьцы были порабощены в процессе монгольского вторжения в Китай . [169] По словам японских историков Сугиямы Масааки (杉山正明) и Фунады Ёсиюки (舩田善之), монгольские рабы принадлежали китайцам-ханьцам во времена династии Юань . [170] [171] Рабство принимало различные формы на протяжении всей истории Китая. Сообщается, что оно было отменено как юридически признанный институт, в том числе в законе 1909 года [172] [173], полностью принятом в 1910 году, [174] хотя эта практика продолжалась по крайней мере до 1949 года. [169] Китайские солдаты и пираты династии Тан порабощали корейцев, турок, персов, индонезийцев и людей из Внутренней Монголии, Центральной Азии и северной Индии. [175] [176] Наибольшим источником рабов были южные племена, включая тайцев и аборигенов из южных провинций Фуцзянь, Гуандун, Гуанси и Гуйчжоу. Малайцы, кхмеры, индийцы и «чернокожие» народы (которые были либо австронезийскими негритосами Юго-Восточной Азии и островов Тихого океана, либо африканцами, либо и теми, и другими) также покупались в качестве рабов во времена династии Тан. [177]

В XVII веке во времена династии Цин существовал наследственный рабский народ, называемый Буи Аха ( маньчжурский : booi niyalma ; китайская транслитерация: 包衣阿哈), что является маньчжурским словом, которое буквально переводится как «домосед» и иногда переводится как « нуцай ». Маньчжуры устанавливали близкие личные и патерналистские отношения между хозяевами и их рабами, как сказал Нурхачи: «Хозяин должен любить рабов и есть ту же пищу, что и он». [178] Однако, booi aha «не совсем соответствовал китайской категории «раб-раб» (китайский: 奴僕); вместо этого это были отношения личной зависимости от хозяина, которые в теории гарантировали близкие личные отношения и равное обращение, хотя многие западные ученые напрямую переводили бы «booi» как «раб-раб» (некоторые из «booi» даже имели своего собственного слугу). [169] Китайские мусульмане (тунгане) суфии, обвиняемые в практике сецзяо (еретической религии), наказывались ссылкой в Синьцзян и продажей в качестве рабов другим мусульманам, таким как суфийские беки . [179] Китайцы-ханьцы, совершившие такие преступления, как торговля опиумом, становились рабами беков, эта практика регулировалась законом Цин. [180] Большинство китайцев в Алтишахре были рабами-изгнанниками туркестанских беков. [181] В то время как свободные китайские торговцы, как правило, не вступали в отношения с восточными Туркестанские женщины, некоторые из китайских рабынь, принадлежавших бекам, а также солдаты «Зеленого знамени», знаменосцы и маньчжуры вступали в серьезные по своей природе связи с женщинами из Восточного Туркестана. [182]

.jpg/440px-Gesang_School_(i.e._kisaeng_school).jpg)

Рабство в Корее существовало еще до периода Троецарствия Кореи , в первом веке до нашей эры. [183] Рабство описывалось как «очень важное явление в средневековой Корее, вероятно, более важное, чем в любой другой стране Восточной Азии , но к XVI веку рост населения сделал [его] ненужным». [184] Рабство пришло в упадок примерно в X веке, но вернулось в конце периода Корё , когда Корея также пережила несколько восстаний рабов . [183] В период Чосон в Корее члены класса рабов были известны как ноби . Ноби были социально неотличимы от свободных людей (т. е. среднего и простого классов), за исключением правящего класса янбан , и некоторые обладали правами собственности, а также юридическими и гражданскими правами. Поэтому некоторые ученые утверждают, что неуместно называть их «рабами», [185] в то время как некоторые ученые описывают их как крепостных . [186] [187] Численность населения ноби могла колебаться до одной трети от общей численности населения, но в среднем ноби составляли около 10% от общей численности населения. [183] В 1801 году большинство правительственных ноби были освобождены, [188] и к 1858 году численность населения ноби составляла около 1,5 процента от общей численности населения Кореи. [189] В период Чосон численность населения ноби могла колебаться до одной трети от общей численности населения, но в среднем ноби составляли около 10% от общей численности населения. [183] Система ноби пришла в упадок, начиная с 18 века. [190] С самого начала династии Чосон и особенно с 17 века среди выдающихся мыслителей в Корее существовала резкая критика системы ноби. Даже в правительстве Чосон были признаки изменения отношения к ноби. [191] Король Ёнджо в 1775 году осуществил политику постепенного освобождения , [184] и он, и его преемник король Чонджо внесли много предложений и изменений, которые уменьшили бремя ноби, что привело к освобождению подавляющего большинства правительственных ноби в 1801 году. [191] Кроме того, рост населения, [184] многочисленные беглые рабы, [183] растущая коммерциализация сельского хозяйства и рост класса независимых мелких фермеров способствовали сокращению численности ноби примерно до 1,5% от общей численности населения к 1858 году.[189] Наследственная система ноби была официально отменена около 1886–1887 гг., [183] [189] а остальная часть системы ноби была отменена с реформой Габо 1894 г. [183] [192] Однако рабство полностью не исчезло в Корее до 1930 г., во время правления императорской Японии. Во время оккупации Кореи императорской Японией во время Второй мировой войны некоторые корейцы использовались императорской Японией в качестве принудительного труда в условиях, которые можно сравнить с рабством. [183] [193] В их число входили женщины, которых императорская японская армия принуждала к сексуальному рабству до и во время Второй мировой войны, известные как « женщины для утех ». [183] [193]

После того, как португальцы впервые вступили в контакт с Японией в 1543 году, развилась работорговля, в ходе которой португальцы покупали японцев в качестве рабов в Японии и продавали их в различные места за границей, включая Португалию, на протяжении XVI и XVII веков. [194] [195] Во многих документах упоминается работорговля наряду с протестами против порабощения японцев. Считается, что японские рабы были первыми из своей нации, кто оказался в Европе, и португальцы покупали множество японских рабынь, чтобы привезти их в Португалию для сексуальных целей, как отмечала Церковь [196] в 1555 году. Японских рабынь даже продавали в качестве наложниц азиатским ласкарам и африканским членам экипажа, вместе с их европейскими коллегами, служившими на португальских судах, торгующих в Японии, о чем упоминает Луис Серкейра, португальский иезуит, в документе 1598 года. [197] Японских рабов португальцы привозили в Макао , где они были порабощены португальцами или становились рабами других рабов. [198] [199] Некоторые корейские рабы были куплены португальцами и привезены обратно в Португалию из Японии, где они были среди десятков тысяч корейских военнопленных, переправленных в Японию во время японских вторжений в Корею (1592–1598) . [200] [201] Историки отметили, что в то же время, когда Хидэёси выражал свое возмущение и возмущение по поводу португальской торговли японскими рабами, он занимался массовой работорговлей корейскими военнопленными в Японии. [202] [203] Филиппо Сассетти видел некоторых китайских и японских рабов в Лиссабоне среди большого сообщества рабов в 1578 году, хотя большинство рабов были чернокожими. [204] [205] [206] [207] [208]

Португальцы также ценили рабов с Востока больше, чем чернокожих африканцев и мавров из-за их редкости. Китайские рабы были дороже мавров и чернокожих и демонстрировали высокий статус владельца. [209] Португальцы приписывали китайским, японским и индийским рабам такие качества, как интеллект и трудолюбие. [210] [206] Король Португалии Себастьян опасался, что разгул рабства негативно сказывается на католической прозелитизме, поэтому в 1571 году он приказал запретить его. [211] Хидэёси был настолько возмущен тем, что его собственный японский народ массово продавался в рабство на Кюсю , что 24 июля 1587 года написал письмо иезуитскому вице-провинциалу Гаспару Коэльо, в котором потребовал от португальцев, сиамцев (тайцев) и камбоджийцев прекратить покупать и порабощать японцев и вернуть японских рабов, которые в конечном итоге оказались в Индии. [212] [213] [214] Хидэёси обвинил португальцев и иезуитов в этой работорговле и в результате запретил христианское прозелитизм. [215] [ самоизданный источник ] [216] В 1595 году в Португалии был принят закон, запрещающий продажу и покупку китайских и японских рабов. [217]

Рабство в Индии было широко распространено к 6 веку до н. э., а возможно, даже еще в ведический период . [218] Рабство усилилось во время мусульманского господства в северной Индии после 11 века. [219] Рабство существовало в португальской Индии после 16 века. Голландцы также в основном имели дело с абиссинскими рабами, известными в Индии как хабши или шидес. [220] Аракан/Бенгалия, Малабар и Коромандель оставались крупнейшими источниками принудительного труда до 1660-х годов.

Между 1626 и 1662 годами голландцы экспортировали в среднем 150–400 рабов в год с побережья Аракана и Бенгалии. В течение первых 30 лет существования Батавии индийские и араканские рабы составляли основную рабочую силу Голландской Ост-Индской компании, азиатской штаб-квартиры. Увеличение числа коромандельских рабов произошло во время голода после восстания индийских правителей Наяка Южной Индии (Танджавура, Сенджи и Мадураи) против господства Биджапура (1645) и последующего опустошения сельской местности Танджавура армией Биджапура. По сообщениям, более 150 000 человек были увезены вторгшимися армиями мусульман Декани в Биджапур и Голконду. В 1646 году в Батавию было экспортировано 2118 рабов, подавляющее большинство из южного Короманделя. Некоторые рабы были также приобретены южнее в Тонди, Адирампатнаме и Каялпатнаме. Еще один рост работорговли произошел между 1659 и 1661 годами в Танджавуре в результате серии последовательных набегов Биджапури. В Нагапатнаме, Пуликате и других местах компания закупила 8000–10000 рабов, большая часть которых была отправлена на Цейлон, а небольшая часть была экспортирована в Батавию и Малакку. Наконец, после продолжительной засухи в Мадурае и южном Короманделе в 1673 году, которая усилила затянувшуюся борьбу Мадураев и маратхов за Танджавур и карательные фискальные практики, тысячи людей из Танджавура, в основном дети, были проданы в рабство и экспортированы азиатскими торговцами из Нагапаттинама в Ачех, Джохор и другие рынки рабов.

В сентябре 1687 года 665 рабов были экспортированы англичанами из Форта Св. Георгия, Мадрас. А в 1694–1696 годах, когда война снова опустошила Южную Индию, в общей сложности 3859 рабов были импортированы из Короманделя частными лицами на Цейлон. [221] [222] [223] [224] Объем общей голландской работорговли в Индийском океане оценивается примерно в 15–30% от атлантической работорговли, немного меньше транссахарской работорговли и в полтора-три раза больше объема работорговли на побережье Суахили и Красного моря и работорговли Голландской Вест-Индской компании. [225]

По словам сэра Генри Бартла Фрера (который заседал в Совете вице-короля), в 1841 году в Индии насчитывалось около 8 или 9 миллионов рабов. Около 15% населения Малабара были рабами. Рабство было юридически отменено во владениях Ост-Индской компании Законом о рабстве в Индии 1843 года . [3]

Горные племена в Индокитае «непрерывно преследовались и угонялись в рабство сиамцами (тайцами), анамитами (вьетнамцами) и камбоджийцами». [226] Сиамская военная кампания в Лаосе в 1876 году была описана британским наблюдателем как «превратившаяся в крупномасштабные рейды по охоте за рабами». [226] Перепись, проведенная в 1879 году, показала, что 6% населения малайского султаната Перак были рабами. [227] Порабощенные люди составляли около двух третей населения в части Северного Борнео в 1880-х годах. [227]

Рабы ( he mōkai ) имели признанную социальную роль в традиционном обществе маори в Новой Зеландии. [228]

На островах Тихого океана и в Австралии, особенно в XIX веке, наблюдалось скопление черных дроздов .

Записи о рабстве в Древней Греции начинаются с Микенской Греции . Классические Афины имели самое большое количество рабов, около 80 000 в 6-м и 5-м веках до н. э. [229] По мере того, как Римская республика расширялась, целые народы были порабощены по всей Европе и Средиземноморью. Рабы использовались для труда, а также для развлечений (например, гладиаторы и сексуальные рабыни ). Это угнетение элитным меньшинством в конечном итоге привело к восстаниям рабов (см. Римские войны рабов ); Третью войну рабов возглавил Спартак .

By the late Republican era, slavery had become an economic pillar of Roman wealth, as well as Roman society.[230] It is estimated that 25% or more of the population of Ancient Rome was enslaved, although the actual percentage is debated by scholars and varied from region to region.[231][232] Slaves represented 15–25% of Italy's population,[233] mostly war captives,[233] especially from Gaul[234] and Epirus. Estimates of the number of slaves in the Roman Empire suggest that the majority were scattered throughout the provinces outside of Italy.[233] Generally, slaves in Italy were indigenous Italians.[235] Foreigners (including both slaves and freedmen) born outside of Italy were estimated to have peaked at 5% of the total in the capital, where their number was largest. Those from outside of Europe were predominantly of Greek descent. Jewish slaves never fully assimilated into Roman society, remaining an identifiable minority. These slaves (especially the foreigners) had higher death rates and lower birth rates than natives and were sometimes subjected to mass expulsions.[236] The average recorded age at death for the slaves in Rome was seventeen and a half years (17.2 for males; 17.9 for females).[237]

Slavery in early medieval Europe was so common that the Catholic Church repeatedly prohibited it, or at least the export of Christian slaves to non-Christian lands, as for example at the Council of Koblenz (922), the Council of London (1102) (which aimed mainly at the sale of English slaves to Ireland)[238] and the Council of Armagh (1171). Serfdom, on the contrary, was widely accepted. In 1452, Pope Nicholas V issued the papal bull Dum Diversas, granting the kings of Spain and Portugal the right to reduce any "Saracens (Muslims), pagans and any other unbelievers" to perpetual slavery, legitimizing the slave trade as a result of war.[239] The approval of slavery under these conditions was reaffirmed and extended in his Romanus Pontifex bull of 1455. Large-scale trading in slaves was mainly confined to the South and East of early medieval Europe: the Byzantine Empire and the Muslim world were the destinations, while pagan Central and Eastern Europe (along with the Caucasus and Tartary) were important sources. Viking, Arab, Greek, and Radhanite Jewish merchants were all involved in the slave trade during the Early Middle Ages.[240][241][242] The trade in European slaves reached a peak in the 10th century following the Zanj Rebellion, which dampened the use of African slaves in the Arab world.[243][244]

In Britain, slavery continued to be practiced following the fall of Rome, while sections of Æthelstan's and Hywel the Good's laws dealt with slaves in medieval England and medieval Wales respectively.[245][246] The trade particularly picked up after the Viking invasions, with major markets at Chester[247] and Bristol[248] supplied by Danish, Mercian, and Welsh raiding of one another's borderlands. At the time of the Domesday Book, nearly 10% of the English population were slaves.[249] William the Conqueror introduced a law preventing the sale of slaves overseas.[250] According to historian John Gillingham, by 1200 slavery in the British Isles was non-existent.[251] Slavery had never been authorized by statute within England and Wales, and in 1772, in the case Somerset v Stewart, Lord Mansfield declared that it was also unsupported within England by the common law. The slave trade was abolished by the Slave Trade Act 1807, although slavery remained legal in possessions outside Europe until the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 and the Indian Slavery Act, 1843.[252] However, when England began to have colonies in the Americas, and particularly from the 1640s, African slaves began to make their appearance in England and remained a presence until the eighteenth century. In Scotland, slaves continued to be sold as chattels until late in the eighteenth century (on the second May 1722, an advertisement appeared in the Edinburgh Evening Courant, announcing that a stolen slave had been found, who would be sold to pay expenses, unless claimed within two weeks).[253] For nearly two hundred years in the history of coal mining in Scotland, miners were bonded to their "maisters" by a 1606 Act "Anent Coalyers and Salters". The Colliers and Salters (Scotland) Act 1775 stated that "many colliers and salters are in a state of slavery and bondage" and announced emancipation; those starting work after July 1, 1775, would not become slaves, while those already in a state of slavery could, after 7 or 10 years depending on their age, apply for a decree of the Sheriff's Court granting their freedom. Few could afford this, until a further law in 1799 established their freedom and made this slavery and bondage illegal.[253][254]

The Byzantine-Ottoman wars and the Ottoman wars in Europe brought large numbers of slaves into the Islamic world.[255] To staff its bureaucracy, the Ottoman Empire established a janissary system which seized hundreds of thousands of Christian boys through the devşirme system. They were well cared for but were legally slaves owned by the government and were not allowed to marry. They were never bought or sold. The empire gave them significant administrative and military roles. The system began about 1365; there were 135,000 janissaries in 1826, when the system ended.[256] After the Battle of Lepanto, 12,000 Christian galley slaves were recaptured and freed from the Ottoman fleet.[257] Eastern Europe suffered a series of Tatar invasions, the goal of which was to loot and capture slaves for selling them to Ottomans as jasyr.[258] Seventy-five Crimean Tatar raids were recorded into Poland–Lithuania between 1474 and 1569.[259]

Medieval Spain and Portugal were the scene of almost constant Muslim invasion of the predominantly Christian area. Periodic raiding expeditions were sent from Al-Andalus to ravage the Iberian Christian kingdoms, bringing back booty and slaves. In a raid against Lisbon in 1189, for example, the Almohad caliph Yaqub al-Mansur took 3,000 female and child captives, while his governor of Córdoba, in a subsequent attack upon Silves, Portugal, in 1191, took 3,000 Christian slaves.[260] From the 11th to the 19th century, North African Barbary Pirates engaged in raids on European coastal towns to capture Christian slaves to sell at slave markets in places such as Algeria and Morocco.[261]

The maritime town of Lagos was the first slave market created in Portugal (one of the earliest colonizers of the Americas) for the sale of imported African slaves – the Mercado de Escravos, opened in 1444.[262][263] In 1441, the first slaves were brought to Portugal from northern Mauritania.[263] By 1552, black African slaves made up 10% of the population of Lisbon.[264][265] In the second half of the 16th century, the Crown gave up the monopoly on slave trade, and the focus of European trade in African slaves shifted from import to Europe to slave transports directly to tropical colonies in the Americas – especially Brazil.[263] In the 15th century one-third of the slaves were resold to the African market in exchange of gold.[266]

Until the late 18th century, the Crimean Khanate (a Muslim Tatar state) maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East.[258] The slaves were captured in southern Russia, Poland-Lithuania, Moldavia, Wallachia, and Circassia by Tatar horsemen[267] and sold in the Crimean port of Kaffa.[268] About 2 million mostly Christian slaves were exported over the 16th and 17th centuries[269] until the Crimean Khanate was destroyed by the Russian Empire in 1783.[270]

In Kievan Rus and Muscovy, slaves were usually classified as kholops. According to David P. Forsythe, "In 1649 up to three-quarters of Muscovy's peasants, or 13 to 14 million people, were serfs whose material lives were barely distinguishable from slaves. Perhaps another 1.5 million were formally enslaved, with Russian slaves serving Russian masters."[272] Slavery remained a major institution in Russia until 1723, when Peter the Great converted the household slaves into house serfs. Russian agricultural slaves were formally converted into serfs earlier in 1679.[273] Slavery in Poland was forbidden in the 15th century; in Lithuania, slavery was formally abolished in 1588; they were replaced by the second serfdom.

In Scandinavia, thralldom was abolished in the mid-14th century.[274]

During the Second World War, Nazi Germany effectively enslaved about 12 million people, both those considered undesirable and citizens of conquered countries, with the avowed intention of treating these Untermenschen (sub-humans) as a permanent slave-class of inferior beings who could be worked until they died, and who possessed neither the rights nor the legal status of members of the Aryan race.[275]

Besides Jews, the harshest deportation and forced labour policies were applied to the populations of Poland,[276] Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia. By the end of the war, half of Belarus' population had been killed or deported.[277][278]

Between 1930 and 1960, the Soviet Union created a system of, according to Anne Applebaum and the "perspective of the Kremlin", slave labor camps called the Gulag (Russian: ГУЛаг, romanized: GULag).[279]

Prisoners in these camps were worked to death by a combination of extreme production quotas, physical and psychological brutality, hunger, lack of medical care, and the harsh environment. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who survived eight years of Gulag incarceration, provided firsthand testimony about the camps with the publication of The Gulag Archipelago, after which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.[280][281] Fatality rate was as high as 80% during the first months in many camps. Hundreds of thousands of people, possibly millions, died as a direct result of forced labour under the Soviets.[282]

Golfo Alexopoulos suggests comparing labor in the Gulag with "other forms of slave labor" and notes its "violence of human exploitation" in Illness and Inhumanity in Stalin's Gulag:[283]

Stalin's Gulag was, in many ways, less a concentration camp than a forced labor camp and less a prison system than a system of slavery. The image of the slave appears often in Gulag memoir literature. As Varlam Shalamov wrote: "Hungry and exhausted, we leaned into a horse collar, raising blood blisters on our chests and pulling a stone-filled cart up the slanted mine floor. The collar was the same device used long ago by the ancient Egyptians." Thoughtful and rigorous historical comparisons of Soviet forced labor and other forms of slave labor would be worthy of scholarly attention, in my view. For as in the case of global slavery, the Gulag found legitimacy in an elaborate narrative of difference that involved the presumption of dangerousness and guilt. This ideology of difference and the violence of human exploitation have left lasting legacies in contemporary Russia.

Historian Anne Applebaum writes in the introduction of her book that the word GULAG has come to represent "the system of Soviet slave labor itself, in all its forms and varieties":[284]

The word "GULAG" is an acronym for Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei, or Main Camp Administration, the institution which ran the Soviet camps. But over time, the word has also come to signify the system of Soviet slave labor itself, in all its forms and varieties: labor camps, punishment camps, criminal and political camps, women's camps, children's camps, transit camps. Even more broadly, "Gulag" has come to mean the Soviet repressive system itself, the set of procedures that Alexander Solzhenitsyn once called "our meat grinder": the arrests, the interrogations, the transport in unheated cattle cars, the forced labor, the destruction of families, the years spent in exile, the early and unnecessary deaths.

Applebaum's introduction has been criticized by Gulag researcher Wilson Bell,[285] stating that her book "is, aside from the introduction, a well-done overview of the Gulag, but it did not offer an interpretative framework much beyond Solzhenitsyn's paradigms".[286]

In the earliest known records, slavery is treated as an established institution. The Code of Hammurabi (c. 1760 BC), for example, prescribed death for anyone who helped a slave escape or who sheltered a fugitive.[287] The Bible mentions slavery as an established institution.[3] Slavery existed in Pharaonic Egypt, but studying it is complicated by terminology used by the Egyptians to refer to different classes of servitude over the course of history. Interpretation of the textual evidence of classes of slaves in ancient Egypt has been difficult to differentiate by word usage alone.[288][289] The three apparent types of enslavement in Ancient Egypt: chattel slavery, bonded labour, and forced labour.[290][291][292]