Конфедеративные Штаты Америки ( КША ), обычно называемые Конфедеративными Штатами ( КШ ), Конфедерацией или Югом , были непризнанной отколовшейся [1] республикой на юге США , которая существовала с 8 февраля 1861 года по 9 мая 1865 года. [8] Конфедерация состояла из одиннадцати штатов США , которые объявили о выходе из состава США и воевали против США во время Гражданской войны в США . [8] [9] В состав этих штатов входили Южная Каролина , Миссисипи , Флорида , Алабама , Джорджия , Луизиана , Техас , Вирджиния , Арканзас , Теннесси и Северная Каролина .

С избранием Авраама Линкольна президентом Соединенных Штатов в 1860 году часть южных штатов была убеждена, что их плантационная экономика, зависящая от рабства, находится под угрозой, и начала отделяться от Соединенных Штатов . [1] [10] [11] Конфедерация была образована 8 февраля 1861 года Южной Каролиной, Миссисипи, Флоридой, Алабамой, Джорджией, Луизианой и Техасом. [12] [13] [14] Они приняли новую конституцию, устанавливающую конфедеративное правительство «суверенных и независимых штатов». [15] [16] [17] Некоторые северяне отреагировали, сказав: «Пусть Конфедерация идет с миром!», в то время как некоторые южане хотели сохранить свою лояльность Союзу. Федеральное правительство в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия , и штаты, находящиеся под его контролем, были известны как Союз . [9] [12] [18]

Гражданская война началась 12 апреля 1861 года, когда ополчение Южной Каролины атаковало Форт Самтер . Четыре рабовладельческих штата Верхнего Юга — Вирджиния , Арканзас , Теннесси и Северная Каролина — затем отделились и присоединились к Конфедерации. 22 февраля 1862 года лидеры армии Конфедеративных Штатов восстановили федеральное правительство в Ричмонде, штат Вирджиния , и приняли первый проект Конфедерации 16 апреля 1862 года. К 1865 году федеральное правительство Конфедерации погрузилось в хаос, а Конгресс Конфедеративных Штатов объявил о роспуске , фактически прекратив свое существование как законодательный орган 18 марта. После четырех лет тяжелых боев почти все сухопутные и военно-морские силы Конфедерации либо сдались, либо иным образом прекратили военные действия к маю 1865 года. [19] [20] Самой значительной капитуляцией стала капитуляция генерала Конфедерации Роберта Э. Ли 9 апреля, после чего любые сомнения относительно исхода войны или выживания Конфедерации были развеяны. Администрация президента Конфедерации Дэвиса объявила о роспуске Конфедерации 5 мая. [21] [22] [23]

После войны, в эпоху Реконструкции , Конфедеративные штаты были вновь приняты в Конгресс после того, как каждый из них ратифицировал 13-ю поправку к Конституции США, запрещающую рабство. Мифология Lost Cause , идеализированный взгляд на Конфедерацию, доблестно сражающуюся за правое дело, возникла в десятилетия после войны среди бывших генералов и политиков Конфедерации, а также в таких организациях, как United Daughters of the Confederacy и Sons of Confederate Veterans . Интенсивные периоды активности Lost Cause развернулись на рубеже 20-го века и во время движения за гражданские права 1950-х и 1960-х годов в ответ на растущую поддержку расового равенства . Сторонники стремились обеспечить, чтобы будущие поколения белых южан продолжали поддерживать политику превосходства белой расы, такую как законы Джима Кроу, посредством таких мероприятий, как строительство памятников Конфедерации и влияние на авторов учебников . [24] Современное использование боевого флага Конфедерации началось в основном во время президентских выборов 1948 года , когда боевой флаг использовался диксикратами . Во время движения за гражданские права сторонники расовой сегрегации использовали его для демонстраций. [25] [26]

Консенсус историков, которые рассматривают истоки Гражданской войны в США, сходится во мнении, что сохранение института рабства было главной целью одиннадцати южных штатов (семь штатов до начала войны и четыре штата после ее начала), которые объявили о своем выходе из состава Соединенных Штатов ( Союза ) и объединились в Конфедеративные Штаты Америки (известные как «Конфедерация»). [27] Однако, хотя историки в 21 веке согласны с центральной ролью рабства в конфликте, они резко расходятся во мнениях о том, какие аспекты этого конфликта (идеологические, экономические, политические или социальные) были наиболее важными, а также о причинах, по которым Север отказался позволить южным штатам отделиться. [28] Сторонники псевдоисторической идеологии « проигранного дела» отрицают, что рабство было главной причиной отделения, точка зрения, которая была опровергнута подавляющим количеством исторических доказательств против нее, в частности некоторыми собственными документами о отделении отделившихся штатов . [29]

Основная политическая битва, приведшая к отделению Юга, была по вопросу о том, будет ли разрешено рабство распространяться на западные территории, которым суждено было стать штатами. Первоначально Конгресс принимал новые штаты в Союз парами, один рабский и один свободный . Это поддерживало секционный баланс в Сенате , но не в Палате представителей , поскольку свободные штаты превосходили рабовладельческие штаты по количеству имеющих право голоса избирателей. [30] Таким образом, в середине 19-го века свободный против рабского статуса новых территорий был критическим вопросом, как для Севера, где росли антирабовладельческие настроения, так и для Юга, где рос страх отмены рабства . Другим фактором, приведшим к отделению и формированию Конфедерации, было развитие белого южного национализма в предыдущие десятилетия. [31] Основной причиной, по которой Север отверг отделение, было сохранение Союза, дело, основанное на американском национализме . [32]

Авраам Линкольн победил на президентских выборах 1860 года . Его победа спровоцировала заявления о выходе из состава семи рабовладельческих штатов Глубокого Юга , все из которых были основаны на хлопке, выращиваемом рабским трудом. Они образовали Конфедеративные Штаты Америки после избрания Линкольна в ноябре 1860 года, но до того, как он вступил в должность в марте 1861 года. Националисты на Севере и «юнионисты» на Юге отказались принять заявления о выходе из состава. Ни одно иностранное правительство никогда не признавало Конфедерацию. Правительство США под руководством президента Джеймса Бьюкенена отказалось сдать свои форты, которые находились на территории, на которую претендовала Конфедерация. Сама война началась 12 апреля 1861 года, когда войска Конфедерации обстреляли форт Союза Самтер в гавани Чарльстона, Южная Каролина .

Факторами фона в преддверии Гражданской войны были партийная политика , аболиционизм , аннулирование против отделения , южный и северный национализм, экспансионизм , экономика и модернизация в довоенный период . Как подчеркнула группа историков в 2011 году, «хотя рабство и его разнообразные и многогранные недовольства были основной причиной разобщения, именно разобщение само по себе спровоцировало войну». [33] Историк Дэвид М. Поттер писал: «Проблема для американцев, которые в эпоху Линкольна хотели, чтобы рабы были свободны, заключалась не просто в том, что южане хотели противоположного, но и в том, что они сами лелеяли противоречивую ценность: они хотели, чтобы Конституция, которая защищала рабство, соблюдалась, и чтобы Союз, который был товариществом с рабовладельцами, сохранялся. Таким образом, они были привержены ценностям, которые логически не могли быть согласованы». [34]

Первые съезды отделенных штатов Глубокого Юга отправили своих представителей на съезд Монтгомери в Алабаме 4 февраля 1861 года. Было создано временное правительство, и собрался представительный Конгресс Конфедеративных Штатов Америки. [35]

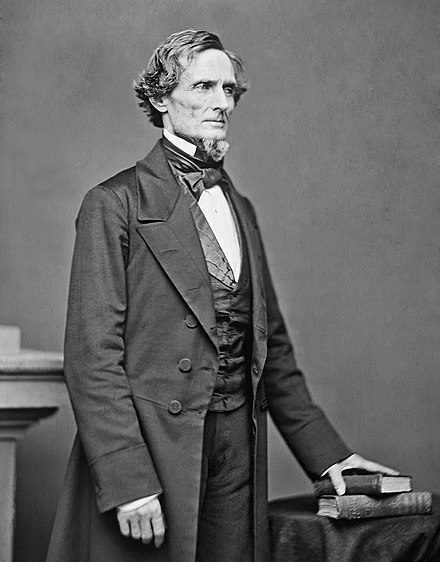

Новый временный президент Конфедерации Джефферсон Дэвис призвал 100 000 человек из ополчений штатов для защиты недавно сформированной Конфедерации. [35] Вся федеральная собственность была конфискована, включая золотые слитки и штампы для чеканки монет на монетных дворах США в Шарлотте , Северная Каролина; Далонеге , Джорджия; и Новом Орлеане . [35] Столица Конфедерации была перенесена из Монтгомери в Ричмонд, Вирджиния, в мае 1861 года. 22 февраля 1862 года Дэвис был инаугурирован в качестве президента сроком на шесть лет. [36]

Администрация Конфедерации проводила политику национальной территориальной целостности, продолжая более ранние усилия штата в 1860–1861 годах по устранению присутствия правительства США. Это включало захват судов США, таможен, почтовых отделений и, что наиболее примечательно, арсеналов и фортов. После атаки Конфедерации и захвата Форта Самтер в апреле 1861 года Линкольн призвал 75 000 ополченцев штатов , чтобы они собрались под его командованием. Заявленной целью было повторно занять американские владения по всему Югу, поскольку Конгресс США не санкционировал их оставление. Сопротивление в Форте Самтер сигнализировало об изменении его политики по сравнению с политикой администрации Бьюкенена. Ответ Линкольна вызвал бурю эмоций. Люди как Севера, так и Юга требовали войны, и сотни тысяч солдат спешили под их знамена. [35]

Сецессионисты утверждали, что Конституция Соединенных Штатов была договором между суверенными штатами, который можно было расторгнуть без консультаций, и каждый штат имел право на отделение. После интенсивных дебатов и общештатных голосований семь хлопковых штатов Глубокого Юга приняли постановления об отделении к февралю 1861 года, в то время как в восьми других рабовладельческих штатах попытки отделения провалились.

Конфедерация расширилась в мае-июле 1861 года (с Вирджинией , Арканзасом , Теннесси , Северной Каролиной ) и распалась в апреле-мае 1865 года. Она была сформирована делегациями из семи рабовладельческих штатов Нижнего Юга , которые объявили о своем отделении. После начала боевых действий в апреле еще четыре рабовладельческих штата отделились и были приняты. Позже два рабовладельческих штата ( Миссури и Кентукки ) и две территории получили места в Конгрессе Конфедерации. [37]

Его создание вытекало из южного национализма и углубляло его, [38] который готовил людей к борьбе за «южное дело». [39] Это «дело» включало поддержку прав штатов , тарифной политики и внутренних улучшений, но прежде всего культурную и финансовую зависимость от экономики Юга, основанной на рабстве. Сближение расы и рабства, политики и экономики подняло вопросы политики, связанные с Югом, до статуса моральных вопросов, образа жизни, слияния любви к вещам Юга и ненависти к вещам Севера. По мере приближения войны политические партии раскололись, а национальные церкви и межгосударственные семьи разделились по секционным линиям. [40] По словам историка Джона М. Коски:

Государственные деятели, возглавлявшие движение за отделение, не стеснялись открыто называть защиту рабства своим главным мотивом... Признание центральной роли рабства в Конфедерации имеет важное значение для понимания Конфедерации. [41]

Южные демократы выбрали Джона Брекинриджа своим кандидатом на президентских выборах 1860 года, но ни в одном южном штате его поддержка не была единодушной, поскольку они зафиксировали по крайней мере некоторое количество голосов избирателей по крайней мере за одного из трех других кандидатов (Авраама Линкольна, Стивена А. Дугласа и Джона Белла ). Поддержка этих трех в совокупности варьировалась от значительного до абсолютного большинства, от 25% в Техасе до 81% в Миссури. [42] Мнения меньшинства были повсюду, особенно в горных и платообразных районах Юга, особенно сосредоточенных в западной Вирджинии и восточном Теннесси. Первые шесть штатов, подписавших Конфедерацию, насчитывали около одной четверти ее населения. Они проголосовали 43% за просоюзных кандидатов. Четыре штата, которые вошли после атаки на Форт Самтер, имели почти половину населения Конфедерации и проголосовали 53% за просоюзных кандидатов. Три штата с большой явкой голосовали за крайности; В Техасе, где проживает 5% населения, 20% проголосовали за просоюзных кандидатов; в Кентукки и Миссури, где проживает четверть населения Конфедерации, за просоюзных кандидатов проголосовало 68%.

После единогласного голосования Южной Каролины о выходе из Союза в 1860 году ни один другой южный штат не рассматривал этот вопрос до 1861 года; когда они это сделали, ни один из них не имел единогласного решения. Во всех штатах были жители, которые отдали значительное количество голосов юнионистов. Голосование за то, чтобы остаться в Союзе, не обязательно означало, что люди симпатизировали Северу. После начала боевых действий многие из тех, кто голосовал за то, чтобы остаться в Союзе, приняли решение большинства и поддержали Конфедерацию. [43] Многие авторы оценивали войну как американскую трагедию — «войну братьев», в которой «брат сражался с братом, отец с сыном, родственник с родственником любой степени родства». [44] [45]

Первоначально некоторые сепаратисты надеялись на мирный уход. Умеренные в Конституционном съезде Конфедерации включили положение против импорта рабов из Африки, чтобы апеллировать к Верхнему Югу. Нерабовладельческие штаты могли присоединиться, но радикалы добились требования двух третей голосов в обеих палатах Конгресса, чтобы принять их. [46]

До вступления Линкольна в должность 4 марта 1861 года семь штатов объявили о своем выходе из состава Соединенных Штатов. После нападения Конфедерации на форт Самтер 12 апреля 1861 года и последующего призыва Линкольна к войскам еще четыре штата объявили о своем выходе из состава Соединенных Штатов.

Кентукки объявили нейтралитет, но после того, как войска Конфедерации вошли, законодательный орган штата попросил войска Союза вытеснить их. Делегаты из 68 округов Кентукки были отправлены на Расселвилльскую конвенцию, которая подписала Указ о сецессии. Кентукки был принят в Конфедерацию 10 декабря 1861 года, и Боулинг-Грин стал его первой столицей. В начале войны Конфедерация контролировала более половины Кентукки, но в значительной степени утратила контроль в 1862 году. Отколовшееся правительство Конфедерации Кентукки переехало, чтобы сопровождать западные армии Конфедерации, и никогда не контролировало население штата после 1862 года. К концу войны 90 000 кентуккицев сражались за Союз, по сравнению с 35 000 за Конфедерацию. [47]

В Миссури был одобрен конституционный съезд и избраны делегаты. Съезд отклонил отделение 89–1 19 марта 1861 года. [48] Губернатор предпринял маневры, чтобы взять под контроль арсенал Сент-Луиса и ограничить федеральные передвижения. Это привело к конфронтации, и в июне федеральные силы вытеснили его и Генеральную ассамблею из Джефферсон-Сити. Исполнительный комитет съезда созвал членов в июле, объявил государственные должности вакантными и назначил временное правительство штата юнионистами. [49] Изгнанный губернатор созвал оставшуюся часть сессии бывшей Генеральной ассамблеи в Неошо , и 31 октября 1861 года она приняла указ о отделении . [50] [51] Правительство штата Конфедерации не смогло контролировать значительные части территории Миссури, фактически контролируя только южный Миссури в начале войны. Его столица была в Неошо, затем в Кассвилле , прежде чем его выгнали из штата. Оставшуюся часть войны оно действовало как правительство в изгнании в Маршалле, штат Техас . [52]

Не отделившись, ни Кентукки, ни Миссури не были объявлены восставшими в Прокламации об освобождении Линкольна . Конфедерация признала проконфедеративных претендентов в Кентукки (10 декабря 1861 г.) и Миссури (28 ноября 1861 г.) и предъявила права на эти штаты, предоставив им представительство в Конгрессе и добавив две звезды к флагу Конфедерации. Голосование за представителей в основном проводилось солдатами Конфедерации из Кентукки и Миссури. [53]

Некоторые южные юнионисты обвинили призыв Линкольна к войскам как событие, ускорившее вторую волну отделений. Историк Джеймс Макферсон утверждает, что такие заявления имеют «эгоистическое качество» и считает их вводящими в заблуждение:

Когда телеграф пересказывал сообщения о нападении на Самтер 12 апреля и его сдаче на следующий день, огромные толпы высыпали на улицы Ричмонда, Роли, Нэшвилла и других городов Верхнего Юга, чтобы отпраздновать победу над янки. Эти толпы размахивали флагами Конфедерации и приветствовали славное дело южной независимости. Они требовали, чтобы их собственные штаты присоединились к этому делу. Множество демонстраций прошли с 12 по 14 апреля, прежде чем Линкольн призвал войска. Многие условные юнионисты были унесены этой мощной волной южного национализма; другие были запуганы и замолчали. [54]

Историк Дэниел У. Крофтс не согласен с Макферсоном:

Бомбардировка Форта Самтер сама по себе не уничтожила большинство юнионистов на Верхнем Юге. Поскольку до того, как Линкольн выпустил прокламацию, прошло всего три дня, два события, рассматриваемые ретроспективно, кажутся почти одновременными. Тем не менее, внимательное изучение современных свидетельств... показывает, что прокламация имела гораздо более решающее влияние. [55] ...Многие пришли к выводу... что Линкольн намеренно решил «изгнать все рабовладельческие штаты, чтобы начать с ними войну и уничтожить рабство». [56]

Порядок и даты принятия решений об отделении следующие:

В Вирджинии густонаселенные округа вдоль границ Огайо и Пенсильвании отвергли Конфедерацию. Юнионисты провели съезд в Уилинге в июне 1861 года, установив «восстановленное правительство» с оставшимся законодательным органом , но настроения в регионе оставались глубоко разделенными. В 50 округах, которые должны были составить штат Западная Вирджиния , избиратели из 24 округов проголосовали за разъединение на референдуме Вирджинии 23 мая по постановлению о сецессии. [69] На выборах 1860 года «конституционный демократ» Брекенридж превзошел «конституционного юниониста» Белла в 50 округах на 1900 голосов, 44% против 42%. [70] Округа одновременно поставили более 20 000 солдат каждой стороне конфликта. [71] [72] Представители большинства округов заседали в законодательных собраниях обоих штатов в Уилинге и Ричмонде на протяжении всей войны. [73]

Попытки отделиться от Конфедерации округами Восточного Теннесси были остановлены военным положением. [74] Хотя рабовладельческие Делавэр и Мэриленд не отделились, граждане продемонстрировали разделенную лояльность. Полки Мэрилендцев сражались в армии Ли Северной Вирджинии . [75] В целом, 24 000 мужчин из Мэриленда присоединились к силам Конфедерации, по сравнению с 63 000, которые присоединились к силам Союза. [47] Делавэр так и не выделил полный полк для Конфедерации, но и не освободил рабов, как это сделали Миссури и Западная Вирджиния. Граждане округа Колумбия не предпринимали попыток отделиться, и во время войны референдумы, спонсируемые Линкольном, одобрили компенсационную эмансипацию и конфискацию рабов у «нелояльных граждан». [76]

Граждане Месильи и Тусона в южной части территории Нью-Мексико сформировали съезд по отделению, который проголосовал за присоединение к Конфедерации 16 марта 1861 года и назначил доктора Льюиса С. Оуингса новым губернатором территории. Они выиграли битву при Месилье и создали территориальное правительство со столицей в Месилье. [77] Конфедерация провозгласила Конфедеративную территорию Аризона 14 февраля 1862 года, к северу от 34-й параллели . Маркус Х. МакВилли служил в обоих Конгрессах Конфедерации в качестве делегата Аризоны. В 1862 году кампания Конфедерации в Нью-Мексико по захвату северной половины территории США провалилась, и территориальное правительство Конфедерации в изгнании переехало в Сан-Антонио, штат Техас. [78]

Сторонники Конфедерации на западе Транс-Миссисипи заявили права на части Индейской территории после того, как США эвакуировали федеральные форты и сооружения. Более половины американских индейских войск, участвовавших в войне с Индейской территории, поддержали Конфедерацию. 12 июля 1861 года правительство Конфедерации подписало договор с индейскими народами Чокто и Чикасо . После нескольких сражений армии Союза взяли под контроль территорию. [79]

Индейская территория никогда официально не вступала в Конфедерацию, но получила представительство в Конгрессе. Многие индейцы с территории были интегрированы в регулярные подразделения армии Конфедерации. После 1863 года племенные правительства направили своих представителей в Конгресс Конфедерации : Элиаса Корнелиуса Будино, представлявшего чероки , и Сэмюэля Бентона Каллахана, представлявшего семинолов и криков . Нация чероки присоединилась к Конфедерации. Они практиковали и поддерживали рабство, выступали против его отмены и опасались, что их земли будут захвачены Союзом. После войны индейская территория была упразднена, их черные рабы были освобождены, а племена потеряли часть своих земель. [80]

Монтгомери, штат Алабама , был столицей Конфедеративных Штатов с 4 февраля по 29 мая 1861 года в Капитолии штата Алабама . Шесть штатов создали Конфедерацию там 8 февраля 1861 года. Делегация Техаса заседала в то время, поэтому она считается в «первоначальных семи» штатах Конфедерации; у нее не было поименного голосования, пока ее референдум не сделал отделение «действующим». [81] [82] Постоянная конституция была принята там 12 марта 1861 года. [83]

Постоянная столица, предусмотренная в Конституции Конфедерации, предусматривала государственную уступку округа площадью 100 квадратных миль центральному правительству. Атланта, которая еще не вытеснила Милледжвилл , Джорджия, в качестве столицы штата, подала заявку, отметив свое центральное расположение и железнодорожное сообщение, как и Опелика, Алабама , отметив свое стратегическое внутреннее положение, железнодорожное сообщение и месторождения угля и железа. [84]

Ричмонд, Вирджиния , был выбран в качестве временной столицы в Капитолии штата Вирджиния . Этот шаг был использован вице-президентом Стивенсом и другими, чтобы побудить другие пограничные штаты последовать за Вирджинией в Конфедерацию. В политическом моменте это было проявлением «неповиновения и силы». Война за независимость Юга, несомненно, должна была вестись в Вирджинии, но там также было самое большое на Юге белое население призывного возраста с инфраструктурой, ресурсами и припасами. Политика администрации Дэвиса заключалась в том, что «она должна быть проведена при любых обстоятельствах». [85]

Ричмонд был назван новой столицей 30 мая 1861 года, и там прошли последние две сессии Временного конгресса. [86] По мере того, как война затягивалась, Ричмонд становился переполненным из-за обучения и переводов, логистики и больниц. Цены резко выросли, несмотря на усилия правительства по регулированию цен. Движение в Конгрессе выступило за перенос столицы из Ричмонда. При приближении федеральных армий в середине 1862 года правительственные архивы были готовы к вывозу. По мере развития кампании в глуши Конгресс уполномочил Дэвиса убрать исполнительный департамент и созвать Конгресс на сессию в другом месте в 1864 году и снова в 1865 году. Незадолго до окончания войны правительство Конфедерации эвакуировало Ричмонд, планируя переехать дальше на юг. Из этих планов мало что вышло до капитуляции Ли. [87] Дэвис и большая часть его кабинета бежали в Дэнвилл, Вирджиния , который служил их штаб-квартирой в течение восьми дней.

За четыре года своего существования Конфедерация утвердила свою независимость и назначила десятки дипломатических агентов за рубежом. Ни один из них не был признан иностранным правительством. Правительство США считало, что южные штаты находятся в состоянии мятежа или восстания, и поэтому отказалось от любого формального признания их статуса.

Правительство США никогда не объявляло войну «родственникам и соотечественникам» в Конфедерации, но проводило военные действия, начиная с президентской прокламации, выпущенной 15 апреля 1861 года. [88] Она призывала войска отбить форты и подавить то, что Линкольн позже назвал «восстанием и мятежом». [89] Переговоры в середине войны между двумя сторонами происходили без официального политического признания, хотя законы войны в основном регулировали военные отношения с обеих сторон военного конфликта. [90]

После начала войны с Соединенными Штатами Конфедерация возлагала надежды на выживание на военное вмешательство Великобритании или Франции . Правительство Конфедерации отправило Джеймса М. Мейсона в Лондон, а Джона Слайделла — в Париж. По пути в 1861 году ВМС США перехватили их корабль « Трент» и доставили их в Бостон, международный эпизод, известный как « Дело Трента» . Дипломаты в конечном итоге были освобождены и продолжили свое путешествие. [91] Однако их миссия не увенчалась успехом; историки оценивают их дипломатию как плохую. [92] [ нужна страница ] Ни одна из них не добилась дипломатического признания Конфедерации, не говоря уже о военной помощи.

Конфедераты, которые считали, что « хлопок — король », то есть, что Британия должна была поддерживать Конфедерацию, чтобы получать хлопок, оказались неправы. У британцев были запасы, которых хватило бы больше чем на год, и они разрабатывали альтернативные источники. [93] Соединенное Королевство гордилось тем, что возглавило прекращение трансатлантического порабощения африканцев; к 1833 году Королевский флот патрулировал воды Среднего прохода, чтобы не допустить попадания дополнительных судов с рабами в Западное полушарие. Именно в Лондоне в 1840 году состоялся первый Всемирный съезд против рабства . Чернокожие ораторы-аболиционисты посетили Англию, Шотландию и Ирландию, разоблачая реальность рабства в Америке и опровергая позицию Конфедерации о том, что чернокожие были «неинтеллектуальными, робкими и зависимыми» [94] и «не равны белым людям... высшей расе». Фредерик Дуглас , Генри Хайленд Гарнет , Сара Паркер Ремонд , ее брат Чарльз Ленокс Ремонд , Джеймс В. К. Пеннингтон , Мартин Делани , Сэмюэл Рингголд Уорд и Уильям Г. Аллен провели годы в Британии, где беглые рабы были в безопасности и, как сказал Аллен, «отсутствовали предрассудки против цвета кожи. Здесь цветной человек чувствует себя среди друзей, а не среди врагов». [95] Большая часть британского общественного мнения была против этой практики, а Ливерпуль рассматривался как основная база поддержки Юга. [96]

На протяжении первых лет войны британский министр иностранных дел лорд Джон Рассел , император Франции Наполеон III и, в меньшей степени, британский премьер-министр лорд Палмерстон проявляли интерес к признанию Конфедерации или, по крайней мере, посредничеству в войне. Канцлер казначейства Уильям Гладстон безуспешно пытался убедить Палмерстона вмешаться. [97] К сентябрю 1862 года победа Союза в битве при Энтитеме , предварительная Прокламация об освобождении Линкольна и аболиционистская оппозиция в Британии положили конец этим возможностям. [98] Цена войны с США для Британии была бы высокой: немедленная потеря американских поставок зерна, прекращение британского экспорта в США и конфискация миллиардов фунтов, вложенных в американские ценные бумаги. Война означала бы более высокие налоги в Британии, новое вторжение в Канаду и нападения на британский торговый флот. В середине 1862 года опасения расовой войны (подобной Гаитянской революции 1791–1804 годов) привели к тому, что британцы задумались о вмешательстве по гуманитарным причинам. [99]

Джон Слайделл, эмиссар Конфедеративных Штатов во Франции, преуспел в переговорах о займе в размере 15 000 000 долларов от Эрлангера и других французских капиталистов на бронированные военные корабли и военные поставки. [100] Британское правительство разрешило строительство блокадных кораблей в Британии; они принадлежали и управлялись британскими финансистами и судовладельцами; несколько из них принадлежали и управлялись Конфедерацией. Целью британских инвесторов было приобретение высокодоходного хлопка. [101]

Несколько европейских стран сохранили дипломатов, назначенных в США, но ни одна страна не назначила ни одного дипломата в Конфедерацию. Эти страны признали стороны Союза и Конфедерации воюющими сторонами . В 1863 году Конфедерация выслала европейские дипломатические миссии за то, что они советовали своим подданным отказаться от службы в армии Конфедерации. [102] Агентам как Конфедерации, так и Союза было разрешено открыто работать на британских территориях. [103] Конфедерация назначила Эмброуза Дадли Манна специальным агентом Святого Престола в сентябре 1863 года, но Святой Престол так и не опубликовал заявление в поддержку или признание Конфедерации. В ноябре 1863 года Манн встретился с Папой Пием IX и получил письмо, предположительно адресованное «прославленному и достопочтенному Джефферсону Дэвису, президенту Конфедеративных Штатов Америки»; Манн неправильно перевел адрес. В своем отчете Ричмонду Манн заявил о своем большом дипломатическом достижении, но государственный секретарь Конфедерации Джуда П. Бенджамин сказал Манну, что это было «просто выведенное признание, не связанное с политическими действиями или регулярным установлением дипломатических отношений», и поэтому не придал ему веса официального признания. [104] [105]

Тем не менее, Конфедерация рассматривалась на международном уровне как серьезная попытка государственности, и европейские правительства отправляли военных наблюдателей, чтобы оценить, произошло ли фактическое установление независимости. Среди этих наблюдателей были Артур Лион Фримантл из британского Колдстримского гвардейского полка , который вошел в Конфедерацию через Мексику, Фицджеральд Росс из австрийского гусарского полка и Юстус Шайберт из прусской армии . [106] Европейские путешественники посещали страну и писали отчеты для публикации. Важно отметить, что в 1862 году француз Шарль Жирар в своей книге « Семь месяцев в мятежных штатах во время Североамериканской войны» засвидетельствовал, что «это правительство... больше не является испытательным правительством... но действительно нормальным правительством, выражением народной воли». [107] Фримантл продолжил писать в своей книге «Три месяца в южных штатах» , что он:

...не пытался скрыть какие-либо особенности или недостатки южных людей. Многие люди, несомненно, будут крайне неодобрительно относиться к некоторым их обычаям и привычкам в более дикой части страны; но я думаю, что ни один великодушный человек, каковы бы ни были его политические взгляды, не может поступить иначе, как восхищаться мужеством, энергией и патриотизмом всего населения и мастерством его лидеров в этой борьбе с большими трудностями. И я также придерживаюсь мнения, что многие согласятся со мной в мысли, что народ, в котором все сословия и оба пола проявляют единодушие и героизм, которые никогда не могли быть превзойдены в истории мира, рано или поздно обречен стать великой и независимой нацией. [108]

Французский император Наполеон III заверил дипломата Конфедерации Джона Слайделла, что он сделает «прямое предложение» Великобритании о совместном признании. Император сделал то же самое заверение британским членам парламента Джону А. Робаку и Джону А. Линдсею. Робак, в свою очередь, публично подготовил законопроект для представления в парламент в поддержку совместного англо-французского признания Конфедерации. «Южане имели право быть оптимистами или, по крайней мере, надеяться, что их революция победит или, по крайней мере, выдержит». После катастроф в Виксбурге и Геттисберге в июле 1863 года конфедераты «понесли серьезную потерю уверенности в себе» и отступили на внутреннюю оборонительную позицию. [109] К декабрю 1864 года Дэвис рассматривал возможность пожертвовать рабством, чтобы заручиться признанием и помощью от Парижа и Лондона; он тайно отправил Дункана Ф. Кеннера в Европу с сообщением о том, что война ведется исключительно для «отстаивания наших прав на самоуправление и независимость» и что «никакая жертва не слишком велика, кроме жертвы чести». В сообщении говорилось, что если французское или британское правительства обусловят свое признание чем-либо, Конфедерация согласится на такие условия. [110] Все европейские лидеры видели, что Конфедерация находится на грани поражения. [111]

Наибольшие успехи Конфедерации в области внешней политики были достигнуты с Бразилией и Кубой . В военном отношении это мало что значило. Бразилия представляла собой «народы, наиболее идентичные нам по институтам», [112] в которых рабство оставалось законным до 1880-х годов, а аболиционистское движение было небольшим. Корабли Конфедерации приветствовались в бразильских портах. [113] После войны Бразилия стала основным пунктом назначения тех южан, которые хотели продолжать жить в рабовладельческом обществе, где, как заметил один иммигрант, рабы Конфедерации были дешевы. Капитан-генерал Кубы письменно заявил, что корабли Конфедерации приветствовались и будут защищены в кубинских портах. [112] Историки предполагают, что если бы Конфедерация добилась независимости, она, вероятно, попыталась бы заполучить Кубу в качестве базы для экспансии. [114]

Большинство солдат, вступивших в национальные или государственные военные подразделения Конфедерации, вступили добровольно. Перман (2010) говорит, что историки разделились во мнениях о том, почему миллионы солдат, казалось, так стремились сражаться, страдать и умирать в течение четырех лет:

Некоторые историки подчеркивают, что солдаты Гражданской войны руководствовались политической идеологией, твердо веря в важность свободы, Союза или прав штата, или в необходимость защищать или уничтожать рабство. Другие указывают на менее явно политические причины сражаться, такие как защита своего дома и семьи, или честь и братство, которые нужно сохранить, сражаясь бок о бок с другими мужчинами. Большинство историков сходятся во мнении, что, независимо от того, о чем он думал, когда отправлялся на войну, опыт боя глубоко на него повлиял и иногда повлиял на его причины продолжать сражаться. [115] [116]

Историк гражданской войны Э. Мертон Коултер писал, что для тех, кто хотел обеспечить ее независимость, «Конфедерация была несчастлива в своей неспособности выработать общую стратегию для всей войны». Агрессивная стратегия требовала концентрации наступательных сил. Оборонительная стратегия стремилась к рассредоточению для удовлетворения требований губернаторов, настроенных на местные нужды. Философия управления превратилась в комбинацию «рассеивания с оборонительной концентрацией вокруг Ричмонда». Администрация Дэвиса считала войну чисто оборонительной, «простым требованием, чтобы народ Соединенных Штатов прекратил воевать с нами». [117] Историк Джеймс М. Макферсон критикует наступательную стратегию Ли: «Ли следовал ошибочной военной стратегии, которая обеспечила поражение Конфедерации». [118]

Поскольку правительство Конфедерации теряло контроль над территорией в кампании за кампанией, было сказано, что «огромные размеры Конфедерации сделают ее завоевание невозможным». Враг будет поражен теми же стихиями, которые так часто ослабляли или уничтожали приезжих и переселенцев на Юге. Тепловое истощение, солнечный удар, эндемические заболевания, такие как малярия и тиф, будут соответствовать разрушительной эффективности московской зимы для вторгшихся армий Наполеона. [119]

В начале войны обе стороны считали, что одна великая битва решит исход конфликта; конфедераты одержали неожиданную победу в Первой битве при Булл-Ране , также известной как Первая битва при Манассасе (название, используемое силами Конфедерации). Она свела народ Конфедерации «с ума от радости»; общественность требовала наступления, чтобы захватить Вашингтон, перенести туда столицу Конфедерации и принять Мэриленд в Конфедерацию. [120] Военный совет победивших генералов Конфедерации решил не наступать против большего количества свежих федеральных войск на оборонительных позициях. Дэвис не отменил его. После того, как вторжение Конфедерации в Мэриленд было остановлено в битве при Энтитеме в октябре 1862 года, генералы предложили сосредоточить силы из государственных командований для повторного вторжения на север. Из этого ничего не вышло. [121] В середине 1863 года, во время своего вторжения в Пенсильванию, Ли снова попросил Дэвиса, чтобы Борегар одновременно атаковал Вашингтон войсками, взятыми из Каролин. Но войска там оставались на месте во время Геттисбергской кампании .

Одиннадцать штатов Конфедерации уступали Северу по численности личного состава примерно в четыре раза. Он уступал гораздо больше по военному оборудованию, промышленным объектам, железным дорогам для транспорта и фургонам, снабжающим фронт.

Конфедераты замедлили захватчиков-янки, что дорого обошлось инфраструктуре Юга. Конфедераты сожгли мосты, заложили мины на дорогах и сделали непригодными для использования входы в гавани и внутренние водные пути с помощью затопленных мин (в то время их называли «торпедами»). Коултер сообщает:

Рейнджерам в отрядах от двадцати до пятидесяти человек была присуждена 50%-ная оценка за уничтоженное имущество за линиями Союза, независимо от местоположения или лояльности. Когда федералы заняли Юг, возражения лояльных конфедератов относительно кражи лошадей рейнджерами и беспорядочной тактики выжженной земли за линиями Союза привели к тому, что Конгресс упразднил службу рейнджеров два года спустя. [122]

Конфедерация полагалась на внешние источники военных материалов. Первым источником была торговля с врагом. «Огромное количество военных поставок» поступало через Кентукки, и впоследствии западные армии «в весьма значительной степени» снабжались незаконной торговлей через федеральных агентов и северных частных торговцев. [123] Но эта торговля была прервана в первый год войны речными канонерскими лодками адмирала Портера , поскольку они захватили господство вдоль судоходных рек с севера на юг и с востока на запад. [124] Затем прорыв заморской блокады стал иметь «исключительное значение». [125] 17 апреля президент Дэвис призвал каперов-рейдеров, «милицию моря», вести войну с морской торговлей США. [126] Несмотря на заметные усилия, в ходе войны Конфедерация оказалась неспособной сравниться с Союзом в кораблях и мореходстве, материалах и морском строительстве. [127]

Неизбежным препятствием к успеху в войне массовых армий была нехватка у Конфедерации живой силы и достаточного количества дисциплинированных, экипированных войск на поле боя в точке соприкосновения с противником. Зимой 1862–63 годов Ли заметил, что ни одна из его знаменитых побед не привела к уничтожению армии противника. У него не было резервных войск, чтобы использовать преимущество на поле боя, как это сделал Наполеон. Ли объяснил: «Неоднократно самые многообещающие возможности были упущены из-за нехватки людей, которые могли бы ими воспользоваться, и сама победа была сделана так, чтобы придать видимость поражения, потому что наши ослабленные и истощенные войска не смогли возобновить успешную борьбу против новых сил противника». [128]

Вооружённые силы Конфедерации состояли из трёх видов: армии , флота и корпуса морской пехоты .

28 февраля 1861 года Временный конгресс Конфедерации учредил временную добровольческую армию и передал контроль над военными операциями и полномочия по сбору государственных сил и добровольцев новоизбранному президенту Конфедерации Джефферсону Дэвису . 1 марта 1861 года от имени правительства Конфедерации Дэвис взял на себя управление военной ситуацией в Чарльстоне, Южная Каролина , где ополчение штата Южная Каролина осадило форт Самтер в гавани Чарльстона, удерживаемый небольшим гарнизоном армии США . К марту 1861 года Временный конгресс Конфедерации расширил временные силы и создал более постоянную армию Конфедеративных Штатов.

Общая численность армии Конфедерации неизвестна из-за неполных и уничтоженных записей Конфедерации, но оценки составляют от 750 000 до 1 000 000 солдат. Это не включает неизвестное количество рабов, принужденных к выполнению армейских задач, таких как строительство укреплений и оборонительных сооружений или управление фургонами. [129] Данные о потерях Конфедерации также неполны и ненадежны, оцениваются в 94 000 убитых или смертельно раненых, 164 000 смертей от болезней и от 26 000 до 31 000 смертей в лагерях для военнопленных Союза. Одна неполная оценка составляет 194 026. [ необходима цитата ]

В состав военного руководства Конфедерации входило много ветеранов из армии и флота США , которые вышли из федеральных комиссий и были назначены на руководящие должности. Многие служили в мексикано-американской войне (включая Роберта Э. Ли и Джефферсона Дэвиса), но некоторые, такие как Леонидас Полк (окончивший Вест-Пойнт , но не служивший в армии), имели мало или вообще не имели опыта.

Офицерский корпус Конфедерации состоял из мужчин как из рабовладельческих, так и нерабовладельческих семей. Конфедерация назначала младших и полевых офицеров путем выборов из рядовых. Хотя для Конфедерации не было создано армейской академии, некоторые колледжи (такие как Цитадель и Военный институт Вирджинии ) содержали кадетские корпуса, которые готовили военное руководство Конфедерации. Военно-морская академия была основана в Дрюри-Блафф , Вирджиния [130] в 1863 году, но ни один гардемарин не окончил ее до конца Конфедерации.

Большинство солдат были белыми мужчинами в возрасте от 16 до 28 лет. Медианный год рождения был 1838, поэтому к 1861 году половина солдат была в возрасте 23 лет или старше. [131] Армии Конфедерации было разрешено расформироваться на два месяца в начале 1862 года после того, как истек срок ее краткосрочной службы. Большинство тех, кто был в форме, не хотели повторно записываться после своего годичного обязательства, поэтому 16 апреля 1862 года Конгресс Конфедерации ввел первую массовую воинскую повинность на территории Северной Америки. (Год спустя, 3 марта 1863 года, Конгресс Соединенных Штатов принял Закон о наборе .) Вместо всеобщего призыва первая программа была выборочной с физическими, религиозными, профессиональными и производственными исключениями. Они становились уже по мере развития битвы. Первоначально замены были разрешены, но к декабрю 1863 года они были запрещены. В сентябре 1862 года возрастной предел был увеличен с 35 до 45 лет, а к февралю 1864 года все мужчины моложе 18 и старше 45 лет были призваны в резерв для обороны штата внутри границ штата. К марту 1864 года суперинтендант по призыву сообщил, что по всей Конфедерации каждый офицер в установленной власти, мужчина и женщина, «участвовал в противодействии офицеру, проводящему набор, в исполнении его обязанностей». [132] Несмотря на то, что это оспаривалось в судах штата, верховные суды штатов Конфедерации обычно отклоняли юридические иски против призыва. [133]

Многие тысячи рабов служили личными слугами своих владельцев или нанимались в качестве рабочих, поваров и пионеров. [134] Некоторые освобожденные чернокожие и цветные мужчины служили в местных отрядах ополчения штата Конфедерации, в основном в Луизиане и Южной Каролине, но их офицеры направляли их для «местной обороны, а не для ведения боевых действий». [135] Истощенные потерями и дезертирством, военные страдали от хронической нехватки рабочей силы. В начале 1865 года Конгресс Конфедерации, под влиянием общественной поддержки генерала Ли, одобрил набор в пехотные подразделения чернокожих. Вопреки рекомендациям Ли и Дэвиса, Конгресс отказался «гарантировать свободу чернокожим добровольцам». Было сформировано не более двухсот чернокожих боевых отрядов. [136]

Немедленное начало войны означало, что она велась «Временной» или «Добровольческой армией». Губернаторы штатов сопротивлялись концентрации общенациональных усилий. Некоторые хотели иметь сильную государственную армию для самообороны. Другие опасались больших «Временных» армий, подчиняющихся только Дэвису. [137] При заполнении призыва правительства Конфедерации на 100 000 человек, еще 200 000 были отклонены, поскольку были приняты только те, кто был зачислен «на срок» или добровольцы на двенадцать месяцев, которые привезли свое собственное оружие или лошадей. [138]

Было важно набрать войска; было так же важно предоставить способных офицеров для командования ими. За немногими исключениями Конфедерация обеспечила себя превосходными генеральскими офицерами. Эффективность младших офицеров была «больше, чем можно было бы разумно ожидать». Как и в случае с федералами, политические назначенцы могли быть безразличны. В противном случае офицерский корпус назначался губернатором или избирался зачисленными в подразделение. Продвижение по службе для заполнения вакансий производилось внутри страны независимо от заслуг, даже если сразу же были доступны лучшие офицеры. [139]

Предвидя необходимость в большем количестве «долгоиграющих» людей, в январе 1862 года Конгресс предоставил возможность рекрутерам ротного уровня вернуться домой на два месяца, но их усилия не увенчались успехом из-за поражений Конфедерации на полях сражений в феврале. [140] Конгресс разрешил Дэвису требовать от каждого губернатора определенное количество рекрутов для покрытия нехватки добровольцев. Штаты отреагировали принятием собственных законопроектов. [141]

Ветераны армии Конфедерации в начале 1862 года в основном состояли из двенадцатимесячных добровольцев, срок службы которых подходил к концу. Выборы по реорганизации рядовых распали армию на два месяца. Офицеры умоляли рядовых повторно записаться, но большинство не сделали этого. Те, кто остался, избрали майоров и полковников, чьи результаты привели к рассмотрению офицерских комиссий в октябре. Комиссии вызвали «быстрое и широкомасштабное» сокращение 1700 некомпетентных офицеров. После этого войска будут выбирать только вторых лейтенантов. [142]

В начале 1862 года популярная пресса предположила, что Конфедерации требуется миллион человек под ружьем. Но ветераны-солдаты не завербовались повторно, а более ранние добровольцы-сепаратисты не появлялись снова, чтобы служить на войне. Одна газета из Мэйкона, штат Джорджия , задавалась вопросом, как два миллиона храбрых бойцов Юга вот-вот будут побеждены четырьмя миллионами северян, которых называли трусами. [143]

Конфедерация приняла первый американский закон о всеобщей воинской повинности 16 апреля 1862 года. Белые мужчины Конфедеративных Штатов в возрасте от 18 до 35 лет были объявлены членами армии Конфедерации на три года, и все мужчины, зачисленные тогда, были продлены до трехлетнего срока. Они должны были служить только в подразделениях и под началом офицеров своего штата. Те, кому было моложе 18 и старше 35 лет, могли заменять призывников, в сентябре те, кому было от 35 до 45 лет, стали призывниками. [144] Клич «война богатых и борьба бедных» привел к тому, что Конгресс полностью отменил систему замещения в декабре 1863 года. Все основные лица, которые получали выгоду ранее, получили право на службу. К февралю 1864 года возрастной диапазон был установлен от 17 до 50 лет, лица моложе восемнадцати и старше сорока пяти лет должны были ограничиваться службой в штате. [145]

Воинская повинность Конфедерации не была всеобщей; это была избирательная служба. Первый закон о воинской повинности от апреля 1862 года исключил профессии, связанные с транспортом, связью, промышленностью, министрами, преподаванием и физической подготовкой. Второй закон о воинской повинности от октября 1862 года расширил исключения в промышленности, сельском хозяйстве и отказе по убеждениям. Мошенничество с освобождением от военной службы процветало в медицинских осмотрах, армейских отпусках, церквях, школах, аптеках и газетах. [146]

Сыновья богатых людей были назначены на социально изгой "надсмотрщик" профессию, но эта мера была принята в стране со "всеобщим осуждением". Законодательным инструментом стал противоречивый Закон о двадцати неграх , который специально освобождал одного белого надсмотрщика или владельца для каждой плантации с не менее чем 20 рабами. Дав задний ход шесть месяцев спустя, Конгресс предоставил надсмотрщикам моложе 45 лет возможность быть освобожденными только в том случае, если они занимали эту должность до первого Закона о воинской повинности. [147] Количество должностных лиц, освобожденных от государственной службы и назначенных по протекции губернатора штата, значительно возросло. [148]

Закон о воинской повинности от февраля 1864 года «радикально изменил всю систему» отбора. Он отменил промышленные исключения, предоставив полномочия по деталям президенту Дэвису. Поскольку позор призыва был больше, чем осуждение за тяжкое преступление, система привлекла «примерно столько же добровольцев, сколько и призывников». Многие мужчины на других «неуязвимых» должностях были зачислены тем или иным способом, около 160 000 дополнительных добровольцев и призывников в форме. Тем не менее, имело место уклонение от службы. [150] Для управления призывом было создано Бюро по воинской повинности, чтобы использовать государственных служащих, как разрешали губернаторы штатов. У него была изменчивая карьера «споров, оппозиции и тщетности». Армии назначали альтернативных военных «вербовщиков», чтобы привлекать не одетых в форму призывников в возрасте 17–50 лет и дезертиров. Почти 3000 офицеров были поставлены на эту работу. К концу 1864 года Ли призывал больше войск. «Наши ряды постоянно редеют из-за сражений и болезней, и рекрутов принимается мало; последствия неизбежны». К марту 1865 года призыв на военную службу должен был осуществляться генералами государственных резервов, призывающими мужчин старше 45 и моложе 18 лет. Все исключения были отменены. Эти полки были назначены для набора призывников в возрасте 17–50 лет, возвращения дезертиров и отражения набегов вражеской кавалерии. Служба удерживала мужчин, потерявших только одну руку или ногу в ополчении. В конечном счете, призыв на военную службу оказался неудачным, и его главная ценность заключалась в том, чтобы побудить мужчин стать добровольцами. [151]

Выживание Конфедерации зависело от сильной базы гражданских лиц и солдат, преданных победе. Солдаты хорошо справились, хотя все большее число дезертировало в последний год боевых действий, и Конфедерация так и не преуспела в замене потерь, как это мог сделать Союз. Гражданские лица, хотя и полные энтузиазма в 1861–62 годах, похоже, потеряли веру в будущее Конфедерации к 1864 году и вместо этого стремились защитить свои дома и общины. Как объясняет Рэйбл, «Это сокращение гражданского видения было больше, чем ворчливым либертарианством ; оно представляло собой все более широко распространенное разочарование в эксперименте Конфедерации». [152]

Гражданская война в США началась в апреле 1861 года с победы Конфедерации в битве при форте Самтер в Чарльстоне .

В январе президент Джеймс Бьюкенен попытался пополнить запасы гарнизона пароходом Star of the West , но артиллерия Конфедерации отогнала его. В марте президент Линкольн уведомил губернатора Южной Каролины Пикенса , что без сопротивления Конфедерации пополнению запасов не будет никаких военных подкреплений без дальнейшего уведомления, но Линкольн был готов принудительно пополнить запасы, если это не будет разрешено. Президент Конфедерации Дэвис, находясь в кабинете министров, решил захватить Форт Самтер до прибытия флота помощи, и 12 апреля 1861 года генерал Борегар заставил его сдаться. [154]

После Самтера Линкольн приказал штатам предоставить 75 000 солдат на три месяца, чтобы вернуть форты Чарльстон-Харбор и всю другую федеральную собственность. [155] Это воодушевило сепаратистов в Вирджинии, Арканзасе, Теннесси и Северной Каролине отделиться, а не предоставить войска для марша в соседние южные штаты. В мае федеральные войска пересекли территорию Конфедерации вдоль всей границы от Чесапикского залива до Нью-Мексико. Первыми сражениями были победы Конфедерации при Биг-Бетеле ( Bethel Church, Virginia ), Первом Булл-Ране ( First Manassas ) в Вирджинии в июле и в августе при Уилсон-Крик ( Oak Hills ) в Миссури. Во всех трех сражениях силы Конфедерации не смогли развить свою победу из-за недостаточного снабжения и нехватки свежих войск для развития своих успехов. После каждого сражения федералы сохраняли военное присутствие и занимали Вашингтон, округ Колумбия; Форт-Монро, Вирджиния; и Спрингфилд, Миссури. И Север, и Юг начали подготовку армий для крупных сражений в следующем году. [156] Силы генерала Союза Джорджа Б. Макклеллана овладели большей частью северо-западной Вирджинии в середине 1861 года, сосредоточившись на городах и дорогах; внутренняя часть была слишком большой, чтобы ее контролировать, и стала центром партизанской активности. [157] [158] Генерал Роберт Э. Ли потерпел поражение у горы Чит в сентябре, и до следующего года никаких серьезных наступлений Конфедерации в западной Вирджинии не произошло.

Тем временем флот Союза захватил контроль над большей частью побережья Конфедерации от Вирджинии до Южной Каролины. Он захватил плантации и брошенных рабов. Федералы там начали военную политику сжигания запасов зерна вверх по рекам во внутренние районы, где они не могли занять их. [159] Флот Союза начал блокаду основных южных портов и подготовил вторжение в Луизиану, чтобы захватить Новый Орлеан в начале 1862 года.

За победами 1861 года последовала серия поражений на востоке и западе в начале 1862 года. Чтобы восстановить Союз военной силой, федеральная стратегия состояла в том, чтобы (1) обезопасить реку Миссисипи, (2) захватить или закрыть порты Конфедерации и (3) пойти на Ричмонд. Чтобы обеспечить независимость, Конфедерация намеревалась (1) отразить захватчика на всех фронтах, что стоило бы ему крови и денег, и (2) перенести войну на Север двумя наступлениями, чтобы повлиять на промежуточные выборы.

Большая часть северо-западной Вирджинии находилась под федеральным контролем. [161] В феврале и марте большая часть Миссури и Кентукки были Союзом «оккупированы, консолидированы и использовались в качестве плацдармов для продвижения дальше на юг». После отражения контратаки Конфедерации в битве при Шайло , штат Теннесси, постоянная федеральная оккупация расширилась на запад, юг и восток. [162] Силы Конфедерации переместились на юг вдоль реки Миссисипи в Мемфис, штат Теннесси , где в военно-морском сражении при Мемфисе был потоплен ее флот речной обороны. Конфедераты отступили из северной части Миссисипи и северной части Алабамы. Новый Орлеан был захвачен 29 апреля объединенными силами армии и флота под командованием адмирала США Дэвида Фаррагута , и Конфедерация потеряла контроль над устьем реки Миссисипи. Ей пришлось уступить обширные сельскохозяйственные ресурсы, которые поддерживали морскую логистическую базу Союза. [163]

Хотя конфедераты повсюду терпели крупные поражения, по состоянию на конец апреля Конфедерация все еще контролировала территорию, на которой проживало 72% ее населения. [164] Федеральные силы нарушили Миссури и Арканзас; они прорвались в западную Вирджинию, Кентукки, Теннесси и Луизиану. Вдоль берегов Конфедерации силы Союза закрыли порты и создали гарнизонные плацдармы во всех прибрежных штатах Конфедерации, за исключением Алабамы и Техаса. [165] Хотя ученые иногда оценивают блокаду Союза как неэффективную с точки зрения международного права до последних нескольких месяцев войны, с первых месяцев она мешала конфедеративным каперам, делая «практически невозможным доставку их призов в порты Конфедерации». [166] Британские фирмы создали небольшие флоты компаний по преодолению блокады , такие как John Fraser and Company и S. Isaac, Campbell & Company, в то время как Департамент вооружений обеспечил свои собственные суда по преодолению блокады для специальных грузов с боеприпасами. [167]

Во время Гражданской войны флоты бронированных военных кораблей были впервые развернуты для длительной блокады на море. После некоторого успеха в борьбе с блокадой Союза, в марте броненосец CSS Virginia был вынужден войти в порт и сожжен конфедератами при отступлении. Несмотря на несколько попыток, предпринятых из своих портовых городов, военно-морские силы CSA не смогли прорвать блокаду Союза. Попытки были предприняты броненосцами коммодора Джозайи Тэттнелла III из Саванны в 1862 году с CSS Atlanta . [168] Министр ВМС Стивен Мэллори возлагал надежды на броненосный флот, построенный в Европе, но они так и не оправдались. С другой стороны, четыре новых коммерческих рейдера, построенных в Англии, служили Конфедерации, и несколько быстрых блокадных кораблей были проданы в портах Конфедерации. Они были преобразованы в крейсеры для совершения коммерческих рейдов и укомплектованы их британскими экипажами. [169]

На востоке силы Союза не смогли приблизиться к Ричмонду. Генерал Макклеллан высадил свою армию на Нижнем полуострове Вирджинии. Ли впоследствии положил конец этой угрозе с востока, затем генерал Союза Джон Поуп атаковал по суше с севера, но был отбит при Втором Булл-Ране ( Втором Манассасе ). Удар Ли на север был отражен у Антиетама, Мэриленд, затем наступление генерал-майора Союза Эмброуза Бернсайда было катастрофически остановлено у Фредериксбурга, Вирджиния, в декабре. Затем обе армии отправились на зимние квартиры, чтобы набрать и обучиться к предстоящей весне. [170]

В попытке перехватить инициативу, наказать, защитить фермы в середине вегетационного периода и повлиять на выборы в Конгресс США, в августе и сентябре 1862 года были предприняты два крупных вторжения Конфедерации на территорию Союза. Как вторжение Брэкстона Брэгга в Кентукки, так и вторжение Ли в Мэриленд были решительно отражены, в результате чего конфедераты контролировали лишь 63% его населения. [164] Исследователь гражданской войны Аллан Невинс утверждает, что 1862 год был стратегическим пиком Конфедерации. [171] Неудачи двух вторжений были приписаны одним и тем же неисправимым недостаткам: нехватка рабочей силы на фронте, нехватка припасов, включая исправную обувь, и истощение после длительных маршей без достаточного количества продовольствия. [172] Также в сентябре генерал Конфедерации Уильям У. Лоринг вытеснил федеральные силы из Чарльстона, Вирджиния , и долины Канова на западе Вирджинии, но из-за отсутствия подкреплений Лоринг оставил свои позиции, и к ноябрю регион снова оказался под федеральным контролем. [173] [174]

Неудачная кампания в Среднем Теннесси завершилась 2 января 1863 года в безрезультатной битве при реке Стоунс ( Мерфрисборо ), обе стороны потеряли самый большой процент потерь, понесенных во время войны. За этим последовало еще одно стратегическое отступление сил Конфедерации. [175] Конфедерация одержала значительную победу в апреле 1863 года, отразив наступление федералов на Ричмонд в Чанселорсвилле , но Союз укрепил позиции вдоль побережья Вирджинии и Чесапикского залива.

Без эффективного ответа на федеральные канонерские лодки, речной транспорт и снабжение, Конфедерация потеряла реку Миссисипи после захвата Виксбурга , Миссисипи, и Порт-Хадсона в июле, положив конец южному доступу к трансмиссисипскому Западу. Июль принес кратковременные контратаки, рейд Моргана в Огайо и бунты по призыву в Нью-Йорке . Удар Роберта Э. Ли в Пенсильвании был отражен в Геттисберге , Пенсильвания, несмотря на знаменитую атаку Пикетта и другие акты доблести. Южные газеты оценили кампанию как «Конфедераты не одержали победы, как и враг».

Сентябрь и ноябрь оставили Конфедерации сдавать Чаттанугу , Теннесси, ворота на Нижний Юг. [176] Оставшуюся часть войны боевые действия были ограничены внутри Юга, что привело к медленной, но непрерывной потере территории. В начале 1864 года Конфедерация все еще контролировала 53% своего населения, но она отступила еще дальше, чтобы восстановить оборонительные позиции. Наступления Союза продолжились Маршем к морю Шермана , чтобы взять Саванну, и Кампанией Гранта в Дикой местности , чтобы окружить Ричмонд и осадить армию Ли в Питерсберге . [163]

В апреле 1863 года Конгресс CS санкционировал создание унифицированного Добровольческого флота, многие из которых были британцами. [177] Всего у Конфедерации было восемнадцать крейсеров, уничтожающих торговлю, что серьезно подорвало федеральную торговлю на море и увеличило ставки страхования судоходства на 900%. [178] Коммодор Тэттнелл снова безуспешно попытался прорвать блокаду Союза на реке Саванна в Джорджии с помощью броненосца в 1863 году. [179] Начиная с апреля 1864 года броненосец CSS Albemarle в течение шести месяцев сражался с канонерскими лодками Союза на реке Роанок в Северной Каролине. [180] В августе федералы закрыли залив Мобайл морским десантным нападением, положив конец торговле на побережье залива к востоку от реки Миссисипи. В декабре битва при Нэшвилле положила конец операциям Конфедерации на западном театре военных действий.

Большое количество семей переселялось в более безопасные места, обычно в отдаленные сельские районы, прихватив с собой домашних рабов, если таковые имелись. Мэри Мэсси утверждает, что эти элитные изгнанники внесли элемент пораженчества в южное мировоззрение. [181]

В первые три месяца 1865 года прошла Федеральная Каролинская кампания , опустошившая большую часть оставшегося центра Конфедерации. «Житница Конфедерации» в Великой долине Вирджинии была занята Филиппом Шериданом . Блокада Союза захватила Форт Фишер в Северной Каролине, а Шерман, наконец, взял Чарльстон, Южная Каролина , сухопутным нападением. [163]

Конфедерация не контролировала ни портов, ни гаваней, ни судоходных рек. Железные дороги были захвачены или прекратили работу. Основные регионы, производящие продовольствие, были опустошены войной или оккупированы. Ее администрация выжила только в трех анклавах территории, на которых проживала лишь треть ее населения. Ее армии были разбиты или расформированы. На конференции Хэмптон-Роудс в феврале 1865 года с Линкольном старшие должностные лица Конфедерации отклонили его приглашение восстановить Союз с компенсацией за освобожденных рабов. [163] Три анклава неоккупированной Конфедерации были южной Вирджинией — Северной Каролиной, центральной Алабамой — Флоридой и Техасом, причем последние два района были не столько из-за какого-либо сопротивления, сколько из-за незаинтересованности федеральных сил в их оккупации. [182] Политика Дэвиса была либо независимость, либо ничего, в то время как армия Ли была охвачена болезнями и дезертирством, едва удерживая окопы, защищающие столицу Джефферсона Дэвиса.

Последний оставшийся порт Конфедерации, прорывающий блокаду, Уилмингтон, Северная Каролина , был потерян . Когда Союз прорвал линии Ли в Питерсберге, Ричмонд немедленно пал. Ли сдал остаток 50 000 человек из Армии Северной Вирджинии в здании суда Аппоматтокса , Вирджиния, 9 апреля 1865 года. [183] «Капитуляция» ознаменовала конец Конфедерации. [184] CSS Stonewall отплыл из Европы, чтобы прорвать блокаду Союза в марте; достигнув Гаваны, Куба, он сдался. Некоторые высокопоставленные чиновники бежали в Европу, но президент Дэвис был схвачен 10 мая ; все оставшиеся сухопутные войска Конфедерации сдались к июню 1865 года. Армия США взяла под контроль территории Конфедерации без мятежа после капитуляции или партизанской войны против них, но мир впоследствии был омрачен большим количеством местного насилия, вражды и убийств из мести. [185] Последнее военное подразделение Конфедерации, торговый рейдер CSS Shenandoah , сдалось 6 ноября 1865 года в Ливерпуле . [186]

Историк Гэри Галлахер пришел к выводу, что Конфедерация капитулировала в начале 1865 года, потому что северные армии подавили «организованное южное военное сопротивление». Население Конфедерации, солдаты и гражданские лица, страдали от материальных лишений и социальных потрясений. [187] Оценка Джефферсона Дэвиса в 1890 году определила: «С захватом столицы, рассеиванием гражданских властей, капитуляцией армий на поле боя и арестом президента Конфедеративные Штаты Америки исчезли... их история отныне стала частью истории Соединенных Штатов». [188]

В феврале 1861 года лидеры Юга встретились в Монтгомери, штат Алабама, чтобы принять свою первую конституцию, учредив конфедерацию «суверенных и независимых штатов», гарантировав штатам право на республиканскую форму правления. До принятия первой конституции Конфедерации независимые штаты были суверенными республиками, например, «Республика Луизиана», «Республика Миссисипи», «Республика Техас» и т. д. [4] [17]

Вторая конституция Конфедерации была написана в марте 1861 года, которая стремилась заменить конфедерацию федеральным правительством; большая часть этой конституции дословно копировала Конституцию Соединенных Штатов, но содержала несколько явных мер защиты института рабства, включая положения о признании и защите рабства на любой территории Конфедерации. Она сохраняла запрет на международную работорговлю , хотя и делала применение запрета явным для «негров африканской расы» в отличие от ссылки в Конституции США на «таких лиц, которых любой из ныне существующих штатов сочтет нужным допустить». Она защищала существующую внутреннюю торговлю рабами между рабовладельческими штатами.

В некоторых областях вторая Конституция Конфедерации предоставила штатам большие полномочия (или ограничила полномочия центрального правительства больше), чем Конституция США того времени, но в других областях штаты потеряли права, которые они имели в соответствии с Конституцией США. Хотя Конституция Конфедерации, как и Конституция США, содержала пункт о торговле , версия Конфедерации запрещала центральному правительству использовать доходы, собранные в одном штате, для финансирования внутренних улучшений в другом штате. Эквивалент пункта об общем благосостоянии Конституции США в Конституции Конфедерации запрещал защитные тарифы (но разрешал тарифы для обеспечения внутренних доходов) и говорил о «поддержании правительства Конфедеративных Штатов», а не о предоставлении «общего благосостояния». Законодательные органы штатов имели право в некоторых случаях объявлять импичмент должностным лицам правительства Конфедерации. С другой стороны, Конституция Конфедерации содержала пункт о необходимом и надлежащем положении и пункт о верховенстве , которые по сути дублировали соответствующие пункты Конституции США. Конституция Конфедерации также включила в себя каждую из 12 поправок к Конституции США, ратифицированных к тому моменту.

Вторая Конституция Конфедерации была окончательно принята 22 февраля 1862 года, через год после начала Гражданской войны в США, и не включала в себя конкретно положения, разрешающего штатам отделиться; в Преамбуле говорилось о каждом штате, «действующем в своем суверенном и независимом характере», а также о формировании «постоянного федерального правительства ». Во время дебатов по составлению Конституции Конфедерации одно предложение позволяло бы штатам отделиться от Конфедерации. Предложение было внесено, и только делегаты Южной Каролины проголосовали за рассмотрение этого предложения. [189] Конституция Конфедерации также прямо отрицала право штатов запрещать рабовладельцам из других частей Конфедерации ввозить своих рабов в любой штат Конфедерации или вмешиваться в права собственности рабовладельцев, путешествующих между различными частями Конфедерации. В отличие от светского языка Конституции Соединенных Штатов, Конфедеративная конституция открыто просила Божьего благословения («... взывая к милости и руководству Всемогущего Бога...»).

Некоторые историки называют Конфедерацию формой демократии Herrenvolk . [190] [191]

Конвент Монтгомери по созданию Конфедерации и ее исполнительной власти собрался 4 февраля 1861 года. Каждый штат как суверен имел один голос, с тем же размером делегации, что и в Конгрессе США, и обычно присутствовало от 41 до 50 членов. [192] Должности были «временными», ограниченными сроком не более одного года. Одно имя было выдвинуто на пост президента, одно на пост вице-президента. Оба были избраны единогласно, 6–0. [193]

Джефферсон Дэвис был избран временным президентом. Его речь об отставке в Сенате США произвела большое впечатление своим четким обоснованием отделения и его призывом к мирному выходу из Союза к независимости. Хотя он дал понять, что хочет быть главнокомандующим армий Конфедерации, после избрания он занял должность временного президента. Три кандидата на пост временного вице-президента рассматривались накануне выборов 9 февраля. Все они были из Джорджии, и различные делегации, собравшиеся в разных местах, решили, что двое не подойдут, поэтому Александр Х. Стивенс был единогласно избран временным вице-президентом, хотя и с некоторыми частными оговорками. Стивенс был инаугурирован 11 февраля, Дэвис — 18 февраля. [194]

Дэвис и Стивенс были избраны президентом и вице-президентом без сопротивления 6 ноября 1861 года . Они вступили в должность 22 февраля 1862 года.

Коултер заявил: «Ни один президент США никогда не имел более трудной задачи». Вашингтон был инаугурирован в мирное время. Линкольн унаследовал устоявшееся правительство, существовавшее долгое время. Создание Конфедерации было осуществлено людьми, которые считали себя принципиально консервативными. Хотя они и ссылались на свою «революцию», в их глазах это была скорее контрреволюция против изменений, отличных от их понимания учредительных документов США. В инаугурационной речи Дэвиса он объяснил, что Конфедерация была не революцией французского типа, а передачей власти. Конвенция Монтгомери приняла все законы Соединенных Штатов, пока не была заменена Конгрессом Конфедерации. [195]

Постоянная конституция предусматривала президента Конфедеративных Штатов Америки, избираемого на шестилетний срок, но без возможности переизбрания. В отличие от Конституции Соединенных Штатов, Конфедеративная конституция давала президенту возможность наложить вето на законопроект , что также было доступно некоторым губернаторам штатов.

Конгресс Конфедерации мог отменить как общее, так и постатейное вето теми же двумя третями голосов, которые требуются в Конгрессе США . Кроме того, ассигнования, не запрошенные специально исполнительной властью, требовали принятия двумя третями голосов в обеих палатах Конгресса. Единственным человеком, который был президентом, был Джефферсон Дэвис , поскольку Конфедерация потерпела поражение до завершения его срока.

Единственными двумя «формальными, национальными, функционирующими, гражданскими административными органами» на юге времен Гражданской войны были администрация Джефферсона Дэвиса и Конфедеративные конгрессы. Конфедерация была начата Временным конгрессом на съезде в Монтгомери, штат Алабама, 28 февраля 1861 года. Временный конфедеративный конгресс был однопалатным собранием; каждый штат имел один голос. [196]

Постоянный Конгресс Конфедерации был избран и начал свою первую сессию 18 февраля 1862 года. Постоянный Конгресс Конфедерации следовал формам Соединенных Штатов с двухпалатным законодательным органом. В Сенате было по два человека от штата, двадцать шесть сенаторов. Палата насчитывала 106 представителей, распределенных между свободным и рабским населением в каждом штате. Два Конгресса заседали в течение шести сессий до 18 марта 1865 года. [196]

The political influences of the civilian, soldier vote and appointed representatives reflected divisions of political geography of a diverse South. These in turn changed over time relative to Union occupation and disruption, the war impact on the local economy, and the course of the war. Without political parties, key candidate identification related to adopting secession before or after Lincoln's call for volunteers to retake Federal property. Previous party affiliation played a part in voter selection, predominantly secessionist Democrat or unionist Whig.[197]

The absence of political parties made individual roll call voting all the more important, as the Confederate "freedom of roll-call voting [was] unprecedented in American legislative history."[198] Key issues throughout the life of the Confederacy related to (1) suspension of habeas corpus, (2) military concerns such as control of state militia, conscription and exemption, (3) economic and fiscal policy including impressment of slaves, goods and scorched earth, and (4) support of the Jefferson Davis administration in its foreign affairs and negotiating peace.[199]

The Confederate Constitution outlined a judicial branch of the government, but the ongoing war and resistance from states-rights advocates, particularly on the question of whether it would have appellate jurisdiction over the state courts, prevented the creation or seating of the "Supreme Court of the Confederate States". Thus, the state courts generally continued to operate as they had done, simply recognizing the Confederate States as the national government.[200]

Confederate district courts were authorized by Article III, Section 1, of the Confederate Constitution,[201] and President Davis appointed judges within the individual states of the Confederate States of America.[202] In many cases, the same US Federal District Judges were appointed as Confederate States District Judges. Confederate district courts began reopening in early 1861, handling many of the same type cases as had been done before. Prize cases, in which Union ships were captured by the Confederate Navy or raiders and sold through court proceedings, were heard until the blockade of southern ports made this impossible. After a Sequestration Act was passed by the Confederate Congress, the Confederate district courts heard many cases in which enemy aliens (typically Northern absentee landlords owning property in the South) had their property sequestered (seized) by Confederate Receivers.

When the matter came before the Confederate court, the property owner could not appear because he was unable to travel across the front lines between Union and Confederate forces. Thus, the District Attorney won the case by default, the property was typically sold, and the money used to further the Southern war effort. Eventually, because there was no Confederate Supreme Court, sharp attorneys like South Carolina's Edward McCrady began filing appeals. This prevented their clients' property from being sold until a supreme court could be constituted to hear the appeal, which never occurred.[202] Where Federal troops gained control over parts of the Confederacy and re-established civilian government, US district courts sometimes resumed jurisdiction.[203]

Supreme Court – not established.

District Courts – judges

When the Confederacy was formed and its seceding states broke from the Union, it was at once confronted with the arduous task of providing its citizens with a mail delivery system, and, amid the American Civil War, the newly formed Confederacy created and established the Confederate Post Office. One of the first undertakings in establishing the Post Office was the appointment of John H. Reagan to the position of Postmaster General, by Jefferson Davis in 1861. This made him the first Postmaster General of the Confederate Post Office, and a member of Davis's presidential cabinet. Writing in 1906, historian Walter Flavius McCaleb praised Reagan's "energy and intelligence... in a degree scarcely matched by any of his associates".[204]

When the war began, the US Post Office briefly delivered mail from the secessionist states. Mail that was postmarked after the date of a state's admission into the Confederacy through May 31, 1861, and bearing US postage was still delivered.[205] After this time, private express companies still managed to carry some of the mail across enemy lines. Later, mail that crossed lines had to be sent by 'Flag of Truce' and was allowed to pass at only two specific points. Mail sent from the Confederacy to the U.S. was received, opened and inspected at Fortress Monroe on the Virginia coast before being passed on into the U.S. mail stream. Mail sent from the North to the South passed at City Point, also in Virginia, where it was also inspected before being sent on.[206][207]

With the chaos of the war, a working postal system was more important than ever for the Confederacy. The Civil War had divided family members and friends and consequently letter writing increased dramatically across the entire divided nation, especially to and from the men who were away serving in an army. Mail delivery was also important for the Confederacy for a myriad of business and military reasons. Because of the Union blockade, basic supplies were always in demand and so getting mailed correspondence out of the country to suppliers was imperative to the successful operation of the Confederacy. Volumes of material have been written about the Blockade runners who evaded Union ships on blockade patrol, usually at night, and who moved cargo and mail in and out of the Confederate States throughout the course of the war. Of particular interest to students and historians of the American Civil War is Prisoner of War mail and Blockade mail as these items were often involved with a variety of military and other war time activities. The postal history of the Confederacy along with surviving Confederate mail has helped historians document the various people, places and events that were involved in the American Civil War as it unfolded.[208]

The Confederacy actively used the army to arrest people suspected of loyalty to the United States. Historian Mark Neely found 4,108 names of men arrested and estimated a much larger total.[209] The Confederacy arrested pro-Union civilians in the South at about the same rate as the Union arrested pro-Confederate civilians in the North.[210] Neely argues:

The Confederate citizen was not any freer than the Union citizen – and perhaps no less likely to be arrested by military authorities. In fact, the Confederate citizen may have been in some ways less free than his Northern counterpart. For example, freedom to travel within the Confederate states was severely limited by a domestic passport system.[211]

Across the South, widespread rumors alarmed the whites by predicting the slaves were planning some sort of insurrection. Patrols were stepped up. The slaves did become increasingly independent, and resistant to punishment, but historians agree there were no insurrections. In the invaded areas, insubordination was more the norm than was loyalty to the old master; Bell Wiley says, "It was not disloyalty, but the lure of freedom." Many slaves became spies for the North, and large numbers ran away to federal lines.[212]

According to the 1860 United States census, the 11 states that seceded had the highest percentage of slaves as a proportion of their population, representing 39% of their total population. The proportions ranged from a majority in South Carolina (57.2%) and Mississippi (55.2%) to about a quarter in Arkansas (25.5%) and Tennessee (24.8%).

Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order of the U.S. government on January 1, 1863, changed the legal status of three million slaves in designated areas of the Confederacy from "slave" to "free". The long-term effect was that the Confederacy could not preserve the institution of slavery and lost the use of the core element of its plantation labor force. Slaves were legally freed by the Proclamation, and became free by escaping to federal lines, or by advances of federal troops. Over 200,000 freed slaves were hired by the federal army as teamsters, cooks, launderers and laborers, and eventually as soldiers.[213][214] Plantation owners, realizing that emancipation would destroy their economic system, sometimes moved their slaves as far as possible out of reach of the Union army.[215]

Though the concept was promoted within certain circles of the Union hierarchy during and immediately following the war, no program of reparations for freed slaves was ever attempted. Unlike other Western countries, such as Britain and France, the U.S. government never paid compensation to Southern slave owners for their "lost property". The only place compensated emancipation was carried out was the District of Columbia.[216][217]

According to the 1860 United States census, about 31% of free households in the eleven states that would join the Confederacy owned slaves. Most whites were subsistence farmers who traded their surpluses locally.