Берлин [a] является столицей и крупнейшим городом Германии , как по площади, так и по численности населения . [11] Его более 3,85 миллионов жителей [12] делают его самым густонаселенным городом Европейского Союза , если измерять численность населения в пределах города. [13] Город также является одной из земель Германии и третьей по величине землей в стране с точки зрения площади. Берлин окружен землей Бранденбург , а столица Бранденбурга Потсдам находится неподалеку. Городская территория Берлина имеет население более 4,5 миллионов человек и, следовательно, является самой густонаселенной городской территорией в Германии. [5] [14] Столичный регион Берлин -Бранденбург насчитывает около 6,2 миллионов жителей и является вторым по величине столичным регионом Германии после Рейнско-Рурского региона и шестым по величине столичным регионом по ВВП в Европейском Союзе . [15]

Берлин был построен вдоль берегов реки Шпрее , которая впадает в Хафель в западном районе Шпандау . Город включает озера в западном и юго-восточном районах, крупнейшее из которых — Мюггельзее . Около трети площади города составляют леса, парки и сады , реки, каналы и озера. [16]

Впервые задокументированный в 13 веке [10] и находящийся на пересечении двух важных исторических торговых путей , [17] Берлин был назначен столицей маркграфства Бранденбург (1417–1701), королевства Пруссия (1701–1918), Германской империи (1871–1918), Веймарской республики (1919–1933) и нацистской Германии (1933–1945). Берлин служил научным, художественным и философским центром в эпоху Просвещения , неоклассицизма и немецких революций 1848–1849 годов . В эпоху грюндерства экономический бум , вызванный индустриализацией, спровоцировал быстрый рост населения в Берлине. В 1920-х годах Берлин был третьим по величине городом в мире по численности населения. [18]

После Второй мировой войны и последовавшей за оккупацией Берлина город был разделен на Западный Берлин и Восточный Берлин , разделенные Берлинской стеной . [19] Восточный Берлин был объявлен столицей Восточной Германии, в то время как Бонн стал столицей Западной Германии. После объединения Германии в 1990 году Берлин снова стал столицей всей Германии. Благодаря своему географическому положению и истории Берлин называют «сердцем Европы». [20] [21] [22]

Экономика Берлина основана на высоких технологиях и секторе услуг , охватывая широкий спектр творческих отраслей , стартапов , исследовательских учреждений и медиакорпораций. [23] [24] Берлин служит континентальным узлом для воздушного и железнодорожного сообщения и имеет сложную сеть общественного транспорта . Туризм в Берлине делает город популярным мировым направлением. [25] Значительные отрасли включают информационные технологии, здравоохранение , биомедицинскую инженерию , биотехнологии , автомобильную промышленность и электронику .

В Берлине находится несколько университетов, таких как Берлинский университет имени Гумбольдта , Берлинский технический университет , Берлинский университет искусств и Свободный университет Берлина . Берлинский зоологический сад — самый посещаемый зоопарк в Европе. Студия Бабельсберг — первый в мире крупномасштабный комплекс киностудий, а список фильмов, снятых в Берлине, длинный. [26]

Берлин также является домом для трех объектов Всемирного наследия . Музейный остров , дворцы и парки Потсдама и Берлина , а также жилые комплексы в стиле модернизма в Берлине . [27] Другие достопримечательности включают Бранденбургские ворота , здание Рейхстага , Потсдамскую площадь , Мемориал памяти убитых евреев Европы и Мемориал Берлинской стены . В Берлине есть множество музеев , галерей и библиотек.

Маркграфство Бранденбургское 1237–1618

Бранденбург-Пруссия 1618–1701 Королевство Пруссия 1701–1867

Северогерманский союз 1867–1871 Германская империя 1871–1918 Веймарская республика 1918–1933 Нацистская Германия 1933–1945 Германия, оккупированная союзниками 1945–1949 Западная Германия 1949–1990 Восточная Германия 1949–1990 Германия 1990–настоящее время

Берлин находится на северо-востоке Германии. Большинство городов и деревень на северо-востоке Германии носят названия, происходящие от славянских языков . Типичные германизации для суффиксов топонимов славянского происхождения -ow, -itz, -vitz, -witz, -itzsch и -in , префиксы - Windisch и Wendisch . Название Берлин имеет свои корни в языке западных славян и может быть связано со старым полабским корнем berl-/birl- («болото»). [28]

Из двенадцати районов Берлина пять носят названия славянского происхождения: Панков , Штеглиц-Целендорф , Марцан-Хеллерсдорф , Трептов-Кёпеник и Шпандау . Из девяноста шести районов Берлина двадцать два носят названия славянского происхождения: Альтглинике , Альт-Трептов , Бритц , Бух , Буков , Гатов , Каров , Кладов , Кёпеник , Ланквиц , Любарс , Мальхов , Марцан , Панков , Пренцлауэр Берг , Рудов , Шмёквиц , Шпандау , Stadtrandsiedlung Мальхов , Штеглиц , Тегель и Целендорф .

Самые ранние человеческие поселения в районе современного Берлина датируются примерно 60 000 г. до н. э. [ необходима цитата ] Маска оленя, датируемая 9 000 г. до н. э., приписывается маглемозийской культуре . В 2 000 г. до н. э. плотные человеческие поселения вдоль рек Шпрее и Хафель дали начало лужицкой культуре . [29] Начиная примерно с 500 г. до н. э. германские племена поселились в ряде деревень в более высоких районах современного Берлина. После того, как семноны ушли около 200 г. н. э., последовали бургунды . В 7 веке славянские племена, позже известные как хевелли и шпреване , достигли этого региона.

В XII веке регион попал под немецкое правление как часть маркграфства Бранденбург , основанного Альбертом Медведем в 1157 году. Ранними свидетельствами поселений средневековья в районе современного Берлина являются остатки фундамента дома, датируемого 1270–1290 годами, найденные при раскопках в берлинском районе Митте . [30] Первые письменные упоминания о городах в районе современного Берлина датируются концом XII века. Шпандау впервые упоминается в 1197 году, а Кёпеник — в 1209 году. [31] 1237 год считается датой основания города. [32] Со временем эти два города сформировали тесные экономические и социальные связи и получали прибыль от основного права на два важных торговых пути , один из которых был известен как Via Imperii , а другой торговый путь тянулся от Брюгге до Новгорода . [17] В 1307 году два города заключили союз с общей внешней политикой, хотя их внутреннее управление все еще было разделено. [33]

Члены семьи Гогенцоллернов правили в Берлине до 1918 года, сначала как курфюрсты Бранденбурга, затем как короли Пруссии , и в конечном итоге как германские императоры . В 1443 году Фридрих II Железнозуб начал строительство нового королевского дворца в городе-побратиме Берлин-Кёльн. Протесты горожан против строительства достигли кульминации в 1448 году, в «Берлинском возмущении» («Berliner Unwille»). [34] Официально дворец Берлин-Кёльн стал постоянной резиденцией бранденбургских курфюрстов Гогенцоллернов с 1486 года, когда к власти пришел Иоганн Цицерон . [35] Однако Берлин-Кёльн был вынужден отказаться от своего статуса свободного города Ганзейского союза . В 1539 году курфюрсты и город официально стали лютеранскими . [36]

Тридцатилетняя война между 1618 и 1648 годами опустошила Берлин. Треть его домов была повреждена или разрушена, и город потерял половину своего населения. [37] Фридрих Вильгельм , известный как «Великий курфюрст», сменивший своего отца Георга Вильгельма на посту правителя в 1640 году, инициировал политику содействия иммиграции и религиозной терпимости. [38] С Потсдамским эдиктом в 1685 году Фридрих Вильгельм предложил убежище французским гугенотам . [39]

К 1700 году около 30 процентов жителей Берлина были французами из-за иммиграции гугенотов. [40] Многие другие иммигранты приехали из Богемии , Польши и Зальцбурга . [41]

С 1618 года маркграфство Бранденбург находилось в личной унии с герцогством Прусским . В 1701 году двойственное государство образовало Королевство Пруссия , когда Фридрих III, курфюрст Бранденбургский , короновал себя как король Фридрих I в Пруссии . Берлин стал столицей нового Королевства, [42] заменив Кёнигсберг . Это была успешная попытка централизовать столицу в очень обширном государстве, и это был первый раз, когда город начал расти. В 1709 году Берлин объединился с четырьмя городами Кёльном, Фридрихсвердером, Фридрихштадтом и Доротеенштадтом под названием Берлин, «Haupt- und Residenzstadt Berlin». [33]

В 1740 году к власти пришел Фридрих II, известный как Фридрих Великий (1740–1786). [43] Под властью Фридриха II Берлин стал центром Просвещения , но также был ненадолго оккупирован во время Семилетней войны русской армией. [44] После победы Франции в войне Четвертой коалиции Наполеон Бонапарт вошел в Берлин в 1806 году , но предоставил городу самоуправление. [45] В 1815 году город стал частью новой провинции Бранденбург . [46]

Промышленная революция преобразила Берлин в 19 веке; экономика и население города резко возросли, и он стал главным железнодорожным узлом и экономическим центром Германии. Вскоре появились дополнительные пригороды, которые увеличили площадь и население Берлина. В 1861 году соседние пригороды, включая Веддинг , Моабит и несколько других, были включены в состав Берлина. [47] В 1871 году Берлин стал столицей недавно основанной Германской империи . [48] В 1881 году он стал городским районом, отдельным от Бранденбурга. [49]

В начале 20 века Берлин стал плодородной почвой для немецкого экспрессионистского движения. [50] В таких областях, как архитектура, живопись и кино, были изобретены новые формы художественных стилей. В конце Первой мировой войны в 1918 году Филипп Шейдеман провозгласил республику в здании Рейхстага . В 1920 году Закон о Большом Берлине включил десятки пригородных городов, деревень и поместий вокруг Берлина в расширенный город. Закон увеличил площадь Берлина с 66 до 883 км 2 (с 25 до 341 кв. миль). Население почти удвоилось, и в Берлине проживало около четырех миллионов человек. В эпоху Веймарской республики Берлин претерпел политические волнения из-за экономической неопределенности, но также стал известным центром «ревущих двадцатых» . Мегаполис пережил свой расцвет как крупная мировая столица и был известен своей ведущей ролью в науке, технологии, искусстве, гуманитарных науках, городском планировании, кинематографе, высшем образовании, правительстве и промышленности. Альберт Эйнштейн стал известен общественности в годы своей жизни в Берлине, [51] получив Нобелевскую премию по физике в 1921 году. [52]

В 1933 году к власти пришли Адольф Гитлер и нацистская партия . Гитлер был вдохновлен архитектурой, которую он увидел в Вене , и он желал Германской империи со столицей, которая имела бы монументальный ансамбль. Национал-социалистический режим приступил к монументальным строительным проектам в Берлине, чтобы выразить свою власть и авторитет через архитектуру . Адольф Гитлер и Альберт Шпеер разработали архитектурные концепции для превращения города в мировую столицу Германию ; они так и не были реализованы. [53]

Правление НСДАП уменьшило еврейскую общину Берлина с 160 000 (треть всех евреев в стране) до примерно 80 000 из-за эмиграции между 1933 и 1939 годами. После Хрустальной ночи в 1938 году тысячи евреев города были заключены в близлежащий концентрационный лагерь Заксенхаузен . Начиная с начала 1943 года, многие были депортированы в гетто, такие как Лодзь , и в концентрационные лагеря и лагеря смерти , такие как Освенцим . [54]

В 1936 году в Берлине прошли летние Олимпийские игры , для которых был построен Олимпийский стадион . [55]

Во время Второй мировой войны в Берлине располагалось несколько нацистских тюрем, исправительно-трудовых лагерей, 17 филиалов концлагеря Заксенхаузен для мужчин и женщин, включая подростков, разных национальностей, в том числе поляков, евреев, французов, бельгийцев, чехословаков, русских, украинцев, цыган, голландцев, греков, норвежцев, испанцев, люксембуржцев, немцев, австрийцев, итальянцев, югославов, болгар, венгров [56], лагерь для синти и цыган (см. Цыганский холокост ) [57] и лагерь военнопленных Шталаг III-D для военнопленных союзников разных национальностей.

Во время Второй мировой войны большая часть Берлина была разрушена во время налетов союзников 1943–45 годов и битвы за Берлин 1945 года . Союзники сбросили 67 607 тонн бомб на город, уничтожив 6 427 акров застроенной территории. Около 125 000 мирных жителей были убиты. [58] После окончания Второй мировой войны в Европе в мае 1945 года Берлин принял большое количество беженцев из восточных провинций. Победившие державы разделили город на четыре сектора, аналогичные оккупированной союзниками Германии: сектора союзников Второй мировой войны (США, Великобритания и Франция) образовали Западный Берлин , в то время как Советский Союз образовал Восточный Берлин . [59]

Все четыре союзника Второй мировой войны разделили административную ответственность за Берлин. Однако в 1948 году, когда западные союзники распространили денежную реформу в западных зонах Германии на три западных сектора Берлина, Советский Союз ввел блокаду Берлина на подъездных путях к Западному Берлину и из него, которые полностью лежали на территории, контролируемой Советским Союзом. Берлинский воздушный мост , осуществляемый тремя западными союзниками, преодолел эту блокаду, поставляя продовольствие и другие предметы снабжения в город с июня 1948 года по май 1949 года. [60] В 1949 году в Западной Германии была основана Федеративная Республика Германия , которая в конечном итоге включила в себя все американские, британские и французские зоны, за исключением зон этих трех стран в Берлине, в то время как в Восточной Германии была провозглашена Марксистско-ленинская Германская Демократическая Республика . Западный Берлин официально оставался оккупированным городом, но политически он был связан с Федеративной Республикой Германия, несмотря на географическую изоляцию Западного Берлина. Авиасообщение с Западным Берлином было предоставлено только американским, британским и французским авиакомпаниям.

Основание двух немецких государств усилило напряженность холодной войны . Западный Берлин был окружен территорией Восточной Германии, и Восточная Германия провозгласила восточную часть своей столицей, что западные державы не признали. Восточный Берлин включал большую часть исторического центра города. Правительство Западной Германии обосновалось в Бонне . [61] В 1961 году Восточная Германия начала возводить Берлинскую стену вокруг Западного Берлина, и события переросли в танковое противостояние у контрольно-пропускного пункта Чарли . Западный Берлин теперь был де-факто частью Западной Германии с уникальным правовым статусом, в то время как Восточный Берлин был де-факто частью Восточной Германии. Джон Ф. Кеннеди произнес свою речь « Я — берлинец » 26 июня 1963 года перед ратушей Шёнеберга , расположенной в западной части города, подчеркнув поддержку США Западного Берлина. [62] Берлин был полностью разделен. Хотя для западных граждан был возможен переход на другую сторону через строго контролируемые контрольно-пропускные пункты, для большинства восточных граждан поездки в Западный Берлин или Западную Германию были запрещены правительством Восточной Германии. В 1971 году Соглашение четырех держав гарантировало доступ в Западный Берлин и из него на машине или поезде через Восточную Германию. [63]

В 1989 году, с окончанием Холодной войны и давлением со стороны населения Восточной Германии, 9 ноября пала Берлинская стена , которая впоследствии была в основном снесена. Сегодня в Ист-Сайд-Гэллери хранится большая часть стены. 3 октября 1990 года две части Германии были объединены в Федеративную Республику Германия, и Берлин снова стал воссоединенным городом. После падения Берлинской стены город пережил значительное урбанистическое развитие и до сих пор влияет на решения по городскому планированию.

[64] Вальтер Момпер, мэр Западного Берлина, стал первым мэром воссоединенного города в промежуточный период. [65] Общегородские выборы в декабре 1990 года привели к избранию первого «общеберлинского» мэра, который вступил в должность в январе 1991 года, при этом отдельные должности мэров в Восточном и Западном Берлине к тому времени истекали, и Эберхард Дипген (бывший мэр Западного Берлина) стал первым избранным мэром воссоединенного Берлина. [66] 18 июня 1994 года солдаты из Соединенных Штатов, Франции и Великобритании прошли на параде, который был частью церемоний, ознаменовавших вывод союзных оккупационных войск, что позволило воссоединить Берлин [67] (последние российские войска ушли 31 августа, в то время как окончательный вывод войск западных союзников состоялся 8 сентября 1994 года). 20 июня 1991 года Бундестаг (парламент Германии) проголосовал за перенос столицы Германии из Бонна в Берлин, что было завершено в 1999 году во время канцлерства Герхарда Шрёдера . [68]

Административная реформа Берлина 2001 года объединила несколько округов, сократив их число с 23 до 12. [69]

В 2006 году финал чемпионата мира по футболу прошел в Берлине. [70]

Строительство «Тропы Берлинской стены» (Berliner Mauerweg) началось в 2002 году и было завершено в 2006 году.

В 2016 году в результате террористической атаки, связанной с ИГИЛ , грузовик был намеренно въехал на рождественскую ярмарку рядом с Мемориальной церковью кайзера Вильгельма , в результате чего 13 человек погибли и 55 получили ранения. [71] [72]

В 2018 году более 200 000 протестующих вышли на улицы Берлина с демонстрациями солидарности против расизма в ответ на появление крайне правой политики в Германии . [73]

Аэропорт Берлин-Бранденбург (BER) открылся в 2020 году, на девять лет позже запланированного срока, при этом Терминал 1 был введен в эксплуатацию в конце октября, а рейсы в аэропорт Тегель и из него завершились в ноябре. [74] Из-за падения числа пассажиров в результате пандемии COVID-19 было объявлено о планах закрыть Терминал 5 BER, бывший аэропорт Шенефельд , начиная с марта 2021 года. [75] Соединительное звено линии U-Bahn U5 от Alexanderplatz до Hauptbahnhof, а также новые станции Rotes Rathaus и Unter den Linden открылись 4 декабря 2020 года, станция U-Bahn Museumsinsel открылась в 2021 году, что завершило все новые работы на U5. [76]

Частичное открытие к концу 2020 года музея Форума Гумбольдта , размещенного в реконструированном Берлинском дворце , было отложено до марта 2021 года. [77] 16 сентября 2022 года открытие восточного крыла, последней секции музея Форума Гумбольдта, означало, что музей Форума Гумбольдта был окончательно завершен. Он стал самым дорогим культурным проектом Германии на данный момент. [78]

Правовая основа для объединенного государства Берлин и Бранденбург отличается от других предложений по слиянию государств. Обычно статья 29 Основного закона предусматривает, что для слияния государств требуется федеральный закон. [79] Однако пункт, добавленный к Основному закону в 1994 году, статья 118a, позволяет Берлину и Бранденбургу объединяться без федерального одобрения, требуя референдума и ратификации парламентами обеих земель. [80]

В 1996 году была предпринята неудачная попытка объединения земель Берлин и Бранденбург. [81] Оба имеют общую историю, диалект и культуру, и в 2020 году более 225 000 жителей Бранденбурга ездят в Берлин. Слияние получило почти единогласную поддержку широкой коалиции правительств обеих земель, политических партий, СМИ, деловых ассоциаций, профсоюзов и церквей. [82] Хотя Берлин проголосовал за с небольшим перевесом, в основном благодаря поддержке в бывшем Западном Берлине , избиратели Бранденбурга не одобрили слияние с большим перевесом. Оно провалилось во многом из-за того, что избиратели Бранденбурга не захотели брать на себя большой и растущий государственный долг Берлина и боялись потерять идентичность и влияние в пользу столицы. [81]

Берлин находится на северо-востоке Германии, в районе низменных болотистых лесов с преимущественно плоским рельефом , частью обширной Северо-Европейской равнины , которая простирается от северной Франции до западной России. Берлинский Урстромталь (ледниковая долина ледникового периода ), между низким плато Барним на севере и плато Тельтов на юге, был образован талой водой, стекающей с ледяных щитов в конце последнего вайхзельского оледенения . Шпрее сейчас следует по этой долине. В Шпандау, районе на западе Берлина, Шпрее впадает в реку Хафель , которая течет с севера на юг через западный Берлин. Течение Хафеля больше похоже на цепь озер, крупнейшими из которых являются Тегелер-Зее и Большое Ванзее . Ряд озер также впадает в верхнюю Шпрее, которая протекает через Большое Мюггельзее в восточном Берлине. [83]

Значительная часть современного Берлина простирается на низких плато по обе стороны долины Шпрее. Большие части округов Райникендорф и Панков лежат на плато Барним, в то время как большинство округов Шарлоттенбург-Вильмерсдорф , Штеглиц-Целендорф , Темпельхоф-Шёнеберг и Нойкёльн лежат на плато Тельтов.

Район Шпандау частично находится в пределах Берлинской ледниковой долины, а частично на равнине Науэн, которая тянется к западу от Берлина. С 2015 года холмы Аркенберге в Панкове высотой 122 метра (400 футов) являются самой высокой точкой Берлина. Благодаря утилизации строительного мусора они превзошли Тойфельсберг ( 120,1 м или 394 фута), который сам по себе состоял из обломков руин Второй мировой войны. [84] Мюггельберге высотой 114,7 метра (376 футов) является самой высокой естественной точкой, а самой низкой является Шпектезее в Шпандау высотой 28,1 метра (92 фута). [85]

В Берлине океанический климат ( Кёппен : Cfb ) [86], граничащий с влажным континентальным климатом ( Dfb ). Этот тип климата характеризуется умеренными или очень теплыми летними температурами и холодной, хотя и не очень суровой, зимой. Годовое количество осадков умеренное. [87] [88]

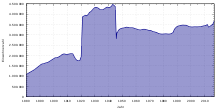

Морозы обычны зимой, и разница температур между сезонами больше, чем типично для многих океанических климатов . Лето теплое и иногда влажное со средней максимальной температурой 22–25 °C (72–77 °F) и минимальной 12–14 °C (54–57 °F). Зима холодная со средней максимальной температурой 3 °C (37 °F) и минимальной от −2 до 0 °C (28–32 °F). Весна и осень, как правило, прохладные или мягкие. Застроенная территория Берлина создает микроклимат, при этом тепло сохраняется в городских зданиях и тротуарах . Температура в городе может быть на 4 °C (7 °F) выше, чем в прилегающих районах. [89] Годовое количество осадков составляет 570 миллиметров (22 дюйма) с умеренным количеством осадков в течение года. Снегопады в основном случаются с декабря по март. [90] Самым жарким месяцем в Берлине был июль 1834 года со средней температурой 23,0 °C (73,4 °F), а самым холодным — январь 1709 года со средней температурой −13,2 °C (8,2 °F). [91] Самым влажным месяцем за всю историю наблюдений был июль 1907 года с 230 миллиметрами (9,1 дюйма) осадков, тогда как самыми сухими были октябрь 1866 года, ноябрь 1902 года, октябрь 1908 года и сентябрь 1928 года, все с 1 миллиметром (0,039 дюйма) осадков. [92]

История Берлина оставила городу полицентрическую столичную зону и эклектичную смесь архитектуры. Современный облик города в основном сформирован немецкой историей 20-го века. 17% зданий Берлина относятся к эпохе грюндерства или более ранним временам, а почти 25% — к 1920-м и 1930-м годам, когда Берлин сыграл роль в зарождении современной архитектуры . [97] [98]

Разрушенный бомбардировками Берлина во время Второй мировой войны, многие из сохранившихся зданий как на Востоке, так и на Западе были снесены в послевоенный период. После воссоединения были реконструированы многие важные исторические сооружения , включая Форум Фридерицианум , Берлинскую государственную оперу , дворец Шарлоттенбург , Жандарменмаркт , Старую комендантуру , а также Городской дворец .

Самые высокие здания в Берлине разбросаны по всей городской территории, особенно на Потсдамской площади , в районе Сити-Вест и Александерплац .

Более трети площади города занимают зеленые зоны и открытые пространства [16], среди которых — Большой Тиргартен , один из крупнейших и самых популярных парков Берлина, расположенный в центре города.

.JPG/440px-Berlin-BerlinerSchloss-2-Asio_(cropped).JPG)

Телебашня Fernsehturm на Александерплац в Митте является одним из самых высоких сооружений в Европейском Союзе высотой 368 м (1207 футов). Построенная в 1969 году, она видна из большинства центральных районов Берлина. Город можно увидеть с ее смотровой площадки высотой 204 метра (669 футов). Начиная отсюда, Карл-Маркс-аллее идет на восток, проспект, выстроенный монументальными жилыми зданиями, спроектированными в стиле социалистического классицизма . Рядом с этой областью находится Красная ратуша ( Rotes Rathaus ) с ее характерной архитектурой из красного кирпича. Перед ней находится Нептунбруннен , фонтан с мифологической группой тритонов , олицетворяющих четыре главные прусские реки, и Нептуном на его вершине.

Бранденбургские ворота — знаковая достопримечательность Берлина и Германии; они являются символом насыщенной европейской истории, единства и мира. Здание Рейхстага — традиционное место заседаний немецкого парламента. Оно было реконструировано британским архитектором Норманом Фостером в 1990-х годах и имеет стеклянный купол над сессионной зоной, что обеспечивает свободный доступ публики к парламентским заседаниям и великолепным видам на город.

East Side Gallery — это выставка под открытым небом произведений искусства, нарисованных непосредственно на последних сохранившихся участках Берлинской стены. Это крупнейшее сохранившееся свидетельство исторического разделения города.

Жандарменмаркт — неоклассическая площадь в Берлине, название которой происходит от штаб-квартиры знаменитого полка Gens d'armes, расположенной здесь в XVIII веке. Ее граничат два собора, выполненных в схожем стиле: Französischer Dom со смотровой площадкой и Deutscher Dom . Konzerthaus (Концертный зал), дом Берлинского симфонического оркестра, находится между двумя соборами.

Музейный остров на реке Шпрее вмещает пять музеев, построенных с 1830 по 1930 год, и является объектом Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО . Реставрация и строительство главного входа во все музеи ( Галерея Джеймса Саймона ), а также реконструкция Берлинского дворца (Stadtschloss) были завершены. [99] [100] Также на острове и рядом с Люстгартеном и дворцом находится Берлинский собор , амбициозная попытка императора Вильгельма II создать протестантский аналог собора Святого Петра в Риме. В большом склепе хранятся останки некоторых членов более ранней прусской королевской семьи. Собор Святой Ядвиги — римско-католический собор Берлина.

Унтер-ден-Линден — это усаженная деревьями улица с востока на запад от Бранденбургских ворот до Берлинского дворца, которая когда-то была главным променадом Берлина. На улице расположено множество классических зданий, а также часть Университета Гумбольдта . Фридрихштрассе была легендарной улицей Берлина в Золотые двадцатые . Она сочетает в себе традиции 20-го века с современной архитектурой сегодняшнего Берлина.

Потсдамская площадь — это целый квартал, построенный с нуля после падения Стены . [101] К западу от Потсдамской площади находится Культурфорум, в котором размещается Галерея искусств , а по бокам от нее — Новая национальная галерея и Берлинская филармония . Мемориал памяти убитых евреев Европы , мемориал Холокоста , находится к северу. [102]

Район вокруг Хакешер Маркт является домом модной культуры с бесчисленными магазинами одежды, клубами, барами и галереями. Сюда входит Хакеше Хёфе , конгломерат зданий вокруг нескольких дворов, реконструированный около 1996 года. Расположенная неподалеку Новая синагога является центром еврейской культуры.

Улица 17 июня , соединяющая Бранденбургские ворота и площадь Эрнст-Ройтер-Платц, служит центральной осью восток-запад. Ее название напоминает о восстаниях в Восточном Берлине 17 июня 1953 года . Примерно на полпути от Бранденбургских ворот находится Großer Stern, круглый островок безопасности, на котором расположена Siegessäule (Колонна Победы). Этот памятник, возведенный в ознаменование побед Пруссии, был перемещен в 1938–39 годах со своего прежнего места перед Рейхстагом.

На Курфюрстендамм находятся некоторые из роскошных магазинов Берлина, а в восточной части на Брайтшайдплац находится Мемориальная церковь кайзера Вильгельма . Церковь была разрушена во время Второй мировой войны и осталась в руинах. Неподалеку на Тауентцинштрассе находится KaDeWe , который, как утверждают, является крупнейшим универмагом континентальной Европы. Ратуша Шёнеберг , где Джон Ф. Кеннеди произнес свою знаменитую речь « Я — берлинец !», находится в Темпельхоф-Шёнеберге .

К западу от центра находится дворец Бельвю — резиденция президента Германии. Дворец Шарлоттенбург , сгоревший во время Второй мировой войны, — крупнейший исторический дворец Берлина.

Радиобашня Funkturm Berlin — решетчатая радиовышка высотой 150 метров (490 футов) на территории ярмарочной площади, построенная между 1924 и 1926 годами. Это единственная смотровая башня, которая стоит на изоляторах и имеет ресторан на высоте 55 метров (180 футов) и смотровую площадку на высоте 126 метров (413 футов) над землей, куда можно подняться на лифте с окнами.

Мост Обербаумбрюкке через реку Шпрее — самый знаковый мост Берлина, соединяющий теперь уже объединенные районы Фридрихсхайн и Кройцберг . По нему движутся транспортные средства, пешеходы и линия метро U1 . Мост был завершен в кирпичном готическом стиле в 1896 году, заменив старый деревянный мост на верхнюю палубу для метро. Центральная часть была снесена в 1945 году, чтобы не допустить переправы Красной Армии . После войны отремонтированный мост служил контрольно-пропускным пунктом и пограничным переходом между советским и американским секторами, а позднее между Восточным и Западным Берлином. В середине 1950-х годов он был закрыт для транспортных средств, а после строительства Берлинской стены в 1961 году движение пешеходов было сильно ограничено. После объединения Германии центральная часть была реконструирована со стальным каркасом, и обслуживание метро возобновилось в 1995 году.

At the end of 2018, the city-state of Berlin had 3.75 million registered inhabitants[103] in an area of 891.1 km2 (344.1 sq mi).[3] The city's population density was 4,206 inhabitants per km2. Berlin is the most populous city proper in the European Union. In 2019, the urban area of Berlin had about 4.5 million inhabitants.[5] As of 2019[update], the functional urban area was home to about 5.2 million people.[104] The entire Berlin-Brandenburg capital region has a population of more than 6 million in an area of 30,546 km2 (11,794 sq mi).[105][3]

In 2014, the city-state Berlin had 37,368 live births (+6.6%), a record number since 1991. The number of deaths was 32,314. Almost 2.0 million households were counted in the city. 54 percent of them were single-person households. More than 337,000 families with children under the age of 18 lived in Berlin. In 2014, the German capital registered a migration surplus of approximately 40,000 people.[106]

National and international migration into the city has a long history. In 1685, after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in France, the city responded with the Edict of Potsdam, which guaranteed religious freedom and tax-free status to French Huguenot refugees for ten years. The Greater Berlin Act in 1920 incorporated many suburbs and surrounding cities of Berlin. It formed most of the territory that comprises modern Berlin and increased the population from 1.9 million to 4 million.

Active immigration and asylum politics in West Berlin triggered waves of immigration in the 1960s and 1970s. Berlin is home to at least 180,000 Turkish and Turkish German residents,[103] making it the largest Turkish community outside of Turkey.[107] In the 1990s the Aussiedlergesetze enabled immigration to Germany of some residents from the former Soviet Union. Today ethnic Germans from countries of the former Soviet Union make up the largest portion of the Russian-speaking community.[108] The last decade experienced an influx from various Western countries and some African regions.[109] A portion of the African immigrants have settled in the Afrikanisches Viertel.[110] Young Germans, EU-Europeans and Israelis have also settled in the city.[111]

In December 2019 there were 777,345 registered residents of foreign nationality and another 542,975 German citizens with a "migration background" (Migrationshintergrund, MH),[103] meaning they or one of their parents immigrated to Germany after 1955. Foreign residents of Berlin originate from about 190 countries.[112] 48 percent of the residents under the age of 15 have a migration background in 2017.[113] Berlin in 2009 was estimated to have 100,000 to 250,000 unregistered inhabitants.[114] Boroughs of Berlin with a significant number of migrants or foreign born population are Mitte, Neukölln and Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg.[115] The number of Arabic speakers in Berlin could be higher than 150,000. There are at least 40,000 Berliners with Syrian citizenship, third only behind Turkish and Polish citizens. The 2015 refugee crisis made Berlin Europe's capital of Arab culture.[116] Berlin is among the cities in Germany that have received the biggest amount of refugees after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. As of November 2022, an estimated 85,000 Ukrainian refugees were registered in Berlin,[117] making Berlin the most popular destination of Ukrainian refugees in Germany.[118]

Berlin has a vibrant expatriate community involving precarious immigrants, illegal immigrants, seasonal workers, and refugees. Therefore, Berlin sustains a broad variety of English-based speakers. Speaking a particular type of English does attract prestige and cultural capital in Berlin.[119]

German is the official and predominant spoken language in Berlin. It is a West Germanic language that derives most of its vocabulary from the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family. German is one of 24 languages of the European Union,[120] and one of the three working languages of the European Commission.

Berlinerisch or Berlinisch is not a dialect linguistically. It is spoken in Berlin and the surrounding metropolitan area. It originates from a Brandenburgish variant. The dialect is now seen more like a sociolect, largely through increased immigration and trends among the educated population to speak standard German in everyday life.

The most commonly spoken foreign languages in Berlin are Turkish, Polish, English, Persian, Arabic, Italian, Bulgarian, Russian, Romanian, Kurdish, Serbo-Croatian, French, Spanish and Vietnamese. Turkish, Arabic, Kurdish, and Serbo-Croatian are heard more often in the western part due to the large Middle Eastern and former-Yugoslavian communities. Polish, English, Russian, and Vietnamese have more native speakers in East Berlin.[121]

Religion in Berlin (2022)[122]

On the report of the 2011 census, approximately 37 percent of the population reported being members of a legally-recognized church or religious organization. The rest either did not belong to such an organization, or there was no information available about them.[123]

The largest religious denomination recorded in 2010 was the Protestant regional church body—the Evangelical Church of Berlin-Brandenburg-Silesian Upper Lusatia (EKBO)—a united church. EKBO is a member of the Protestant Church in Germany (EKD) and of the Union of Protestant Churches in the EKD (UEK). According to the EKBO, their membership accounted for 18.7 percent of the local population, while the Roman Catholic Church had 9.1 percent of residents registered as its members.[124] About 2.7% of the population identify with other Christian denominations (mostly Eastern Orthodox, but also various Protestants).[125] According to the Berlin residents register, in 2018 14.9 percent were members of the Evangelical Church, and 8.5 percent were members of the Catholic Church.[103] The government keeps a register of members of these churches for tax purposes, because it collects church tax on behalf of the churches. It does not keep records of members of other religious organizations which may collect their own church tax, in this way.

In 2009, approximately 249,000 Muslims were reported by the Office of Statistics to be members of mosques and Islamic religious organizations in Berlin,[126] while in 2016, the newspaper Der Tagesspiegel estimated that about 350,000 Muslims observed Ramadan in Berlin.[127] In 2019, about 437,000 registered residents, 11.6% of the total, reported having a migration background from one of the Member states of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.[103][127] Between 1992 and 2011 the Muslim population almost doubled.[128]

About 0.9% of Berliners belong to other religions. Of the estimated population of 30,000–45,000 Jewish residents,[129] approximately 12,000 are registered members of religious organizations.[125]

Berlin is the seat of the Roman Catholic archbishop of Berlin and EKBO's elected chairperson is titled the bishop of EKBO. Furthermore, Berlin is the seat of many Orthodox cathedrals, such as the Cathedral of St. Boris the Baptist, one of the two seats of the Bulgarian Orthodox Diocese of Western and Central Europe, and the Resurrection of Christ Cathedral of the Diocese of Berlin (Patriarchate of Moscow).

The faithful of the different religions and denominations maintain many places of worship in Berlin. The Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church has eight parishes of different sizes in Berlin.[130] There are 36 Baptist congregations (within Union of Evangelical Free Church Congregations in Germany), 29 New Apostolic Churches, 15 United Methodist churches, eight Free Evangelical Congregations, four Churches of Christ, Scientist (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 11th), six congregations of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, an Old Catholic church, and an Anglican church in Berlin. Berlin has more than 80 mosques,[131] ten synagogues,[132] and two Buddhist as well as four Hindu temples.

Since the German reunification on 3 October 1990, Berlin has been one of the three city-states of Germany among the present 16 federal states of Germany. The Abgeordnetenhaus von Berlin (House of Representatives) functions as the city and state parliament, which has 141 seats. Berlin's executive body is the Senate of Berlin (Senat von Berlin). The Senate consists of the Governing Mayor of Berlin (Regierender Bürgermeister), and up to ten senators holding ministerial positions, two of them holding the title of "Mayor" (Bürgermeister) as deputy to the Governing Mayor.[133]

The total annual budget of Berlin in 2015 exceeded €24.5 ($30.0) billion including a budget surplus of €205 ($240) million.[134] The German Federal city state of Berlin owns extensive assets, including administrative and government buildings, real estate companies, as well as stakes in the Olympic Stadium, swimming pools, housing companies, and numerous public enterprises and subsidiary companies.[135][136] The federal state of Berlin runs a real estate portal to advertise commercial spaces or land suitable for redevelopment.[137]

The Social Democratic Party (SPD) and The Left (Die Linke) took control of the city government after the 2001 state election and won another term in the 2006 state election.[138] From the 2016 state election until the 2023 state election, there was a coalition between the Social Democratic Party, the Greens and the Left Party. Since April 2023, the government has been formed by a coalition between the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats.[139]

The Governing Mayor is simultaneously Lord Mayor of the City of Berlin (Oberbürgermeister der Stadt) and Minister President of the State of Berlin (Ministerpräsident des Bundeslandes). The office of the Governing Mayor is in the Rotes Rathaus (Red City Hall). Since 2023, this office has been held by Kai Wegner of the Christian Democrats.[139] He is the first conservative mayor in Berlin in more than two decades.[140]

Berlin is subdivided into 12 boroughs or districts (Bezirke). Each borough has several subdistricts or neighborhoods (Ortsteile), which have roots in much older municipalities that predate the formation of Greater Berlin on 1 October 1920. These subdistricts became urbanized and incorporated into the city later on. Many residents strongly identify with their neighborhoods, colloquially called Kiez. At present, Berlin consists of 96 subdistricts, which are commonly made up of several smaller residential areas or quarters.[citation needed]

Each borough is governed by a borough council (Bezirksamt) consisting of five councilors (Bezirksstadträte) including the borough's mayor (Bezirksbürgermeister). The council is elected by the borough assembly (Bezirksverordnetenversammlung). However, the individual boroughs are not independent municipalities, but subordinate to the Senate of Berlin.[citation needed] The borough's mayors make up the council of mayors (Rat der Bürgermeister), which is led by the city's Governing Mayor and advises the Senate. The neighborhoods have no local government bodies.

Berlin to this day maintains official partnerships with 17 cities.[141] Town twinning between West Berlin and other cities began with its sister city Los Angeles, California, in 1967. East Berlin's partnerships were canceled at the time of German reunification.

Berlin is the capital of the Federal Republic of Germany. The President of Germany, whose functions are mainly ceremonial under the German constitution, has their official residence in Bellevue Palace.[142] Berlin is the seat of the German Chancellor (Prime Minister), housed in the Chancellery building, the Bundeskanzleramt. Facing the Chancellery is the Bundestag, the German Parliament, housed in the renovated Reichstag building since the government's relocation to Berlin in 1998. The Bundesrat ("federal council", performing the function of an upper house) is the representation of the 16 constituent states (Länder) of Germany and has its seat at the former Prussian House of Lords. The total annual federal budget managed by the German government exceeded €310 ($375) billion in 2013.[143]

The relocation of the federal government and Bundestag to Berlin was mostly completed in 1999. However, some ministries, as well as some minor departments, stayed in the federal city Bonn, the former capital of West Germany. Discussions about moving the remaining ministries and departments to Berlin continue.[144]

The Federal Foreign Office and the ministries and departments of Defense, Justice and Consumer Protection, Finance, Interior, Economic Affairs and Energy, Labor and Social Affairs, Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth, Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, Food and Agriculture, Economic Cooperation and Development, Health, Transport and Digital Infrastructure and Education and Research are based in the capital.

Berlin hosts in total 158 foreign embassies[145] as well as the headquarters of many think tanks, trade unions, nonprofit organizations, lobbying groups, and professional associations. Frequent official visits and diplomatic consultations among governmental representatives and national leaders are common in contemporary Berlin.

In 2018, the GDP of Berlin totaled €147 billion, an increase of 3.1% over the previous year.[3] Berlin's economy is dominated by the service sector, with around 84% of all companies doing business in services. In 2015, the total labor force in Berlin was 1.85 million. The unemployment rate reached a 24-year low in November 2015 and stood at 10.0%.[147] From 2012 to 2015 Berlin, as a German state, had the highest annual employment growth rate. Around 130,000 jobs were added in this period.[148]

Important economic sectors in Berlin include life sciences, transportation, information and communication technologies, media and music, advertising and design, biotechnology, environmental services, construction, e-commerce, retail, hotel business, and medical engineering.[149]

Research and development have economic significance for the city.[150] Several major corporations like Volkswagen, Pfizer, and SAP operate innovation laboratories in the city.[151]The Science and Business Park in Adlershof is the largest technology park in Germany measured by revenue.[152] Within the Eurozone, Berlin has become a center for business relocation and international investments.[153]

Many German and international companies have business or service centers in the city. For several years Berlin has been recognized as a major center of business founders.[156] In 2015, Berlin generated the most venture capital for young startup companies in Europe.[157]

Among the 10 largest employers in Berlin are the City-State of Berlin, Deutsche Bahn, largest railway company in the world,[155] the hospital providers Charité and Vivantes, the Federal Government of Germany, the local public transport provider BVG, Siemens and Deutsche Telekom.[158]

Siemens, a Global 500 and DAX-listed company is partly headquartered in Berlin. Other DAX-listed companies headquartered in Berlin are the property company Deutsche Wohnen and the online food delivery service Delivery Hero. The national railway operator Deutsche Bahn,[159] Europe's largest digital publisher[160] Axel Springer as well as the MDAX-listed firms Zalando and HelloFresh and also have their main headquarters in the city. Among the largest international corporations who have their German or European headquarters in Berlin are Bombardier Transportation, Securing Energy for Europe, Coca-Cola, Pfizer, Sony and TotalEnergies.

As of 2023, Sparkassen-Finanzgruppe, a network of public banks that together form the largest financial services group in Germany and in all of Europe, is headquartered in Berlin. The Bundesverband der Deutschen Volksbanken und Raiffeisenbanken has its headquarters in Berlin, managing around 1.200 trillion euros.[161] The three largest banks in the capital are Deutsche Kreditbank, Landesbank Berlin and Berlin Hyp.[162]

Mercedes-Benz Group manufactures cars, and BMW builds motorcycles in Berlin. In 2022, American electric car manufacturer Tesla opened its first European Gigafactory outside the city borders in Grünheide (Mark), Brandenburg. The Pharmaceuticals division of Bayer[163] and Berlin Chemie are major pharmaceutical companies in the city.

Berlin had 788 hotels with 134,399 beds in 2014.[164] The city recorded 28.7 million overnight hotel stays and 11.9 million hotel guests in 2014.[164] Tourism figures have more than doubled within the last ten years and Berlin has become the third-most-visited city destination in Europe. Some of the most visited places in Berlin include: Potsdamer Platz, Brandenburger Tor, the Berlin wall, Alexanderplatz, Museumsinsel, Fernsehturm, the East-Side Gallery, Schloss-Charlottenburg, Zoologischer Garten, Siegessäule, Gedenkstätte Berliner Mauer, Mauerpark, Botanical Garden, Französischer Dom, Deutscher Dom and Holocaust-Mahnmal. The largest visitor groups are from Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain and the United States.[citation needed]

According to figures from the International Congress and Convention Association in 2015, Berlin became the leading organizer of conferences globally, hosting 195 international meetings.[165] Some of these congress events take place on venues such as CityCube Berlin or the Berlin Congress Center (bcc).

The Messe Berlin (also known as Berlin ExpoCenter City) is the main convention organizing company in the city. Its main exhibition area covers more than 160,000 square meters (1,722,226 sq ft). Several large-scale trade fairs like the consumer electronics trade fair IFA, where the first practical audio tape recorder and the first completely electronic television system were first introduced to the public,[166][167][168][169] the ILA Berlin Air Show, the Berlin Fashion Week (including the Premium Berlin and the Panorama Berlin),[170] the Green Week, the Fruit Logistica, the transport fair InnoTrans, the tourism fair ITB and the adult entertainment and erotic fair Venus are held annually in the city, attracting a significant number of business visitors.

_-msu-2021-4274-.jpg/440px-Postfuhramt_(Berlin)_-msu-2021-4274-.jpg)

The creative arts and entertainment business is an important part of Berlin's economy. The sector comprises music, film, advertising, architecture, art, design, fashion, performing arts, publishing, R&D, software,[172] TV, radio, and video games.

In 2014, around 30,500 creative companies operated in the Berlin-Brandenburg metropolitan region, predominantly SMEs. Generating a revenue of 15.6 billion Euro and 6% of all private economic sales, the culture industry grew from 2009 to 2014 at an average rate of 5.5% per year.[173]

Berlin is an important European and German film industry hub.[174] It is home to more than 1,000 film and television production companies, 270 movie theaters, and around 300 national and international co-productions are filmed in the region every year.[150] The historic Babelsberg Studios and the production company UFA are adjacent to Berlin in Potsdam. The city is also home of the German Film Academy (Deutsche Filmakademie), founded in 2003, and the European Film Academy, founded in 1988.

Berlin is home to many magazine, newspaper, book, and scientific/academic publishers and their associated service industries. In addition, around 20 news agencies, more than 90 regional daily newspapers and their websites, as well as the Berlin offices of more than 22 national publications such as Der Spiegel, and Die Zeit reinforce the capital's position as Germany's epicenter for influential debate. Therefore, many international journalists, bloggers, and writers live and work in the city.[citation needed]

Berlin is the central location to several international and regional television and radio stations.[175] The public broadcaster RBB has its headquarters in Berlin as well as the commercial broadcasters MTV Europe and Welt. German international public broadcaster Deutsche Welle has its TV production unit in Berlin, and most national German broadcasters have a studio in the city, including ZDF and RTL.

Berlin has Germany's largest number of daily newspapers, with numerous local broadsheets (Berliner Morgenpost, Berliner Zeitung, Der Tagesspiegel), and three major tabloids, as well as national dailies of varying sizes, each with a different political affiliation, such as Die Welt, Neues Deutschland, and Die Tageszeitung. The Berliner, a monthly magazine, is Berlin's English-language periodical and La Gazette de Berlin a French-language newspaper.[citation needed]

Berlin is also the headquarter of major German-language publishing houses like Walter de Gruyter, Springer, the Ullstein Verlagsgruppe (publishing group), Suhrkamp, and Cornelsen are all based in Berlin. Each of which publishes books, periodicals, and multimedia products.[citation needed]

According to Mercer, Berlin ranked number 13 in the Quality of Living City Ranking in 2019.[176]

Also in 2019, according to Monocle, Berlin occupied the position of the 6th-most-livable city in the world.[177] Economist Intelligence Unit ranked Berlin number 21 of all global cities for livability.[178] In 2019 Berlin was also number 8 on the Global Power City Index.[179] In the same year Berlin was honored for having the best future prospects of all cities in Germany.[180]

Berlin's transport infrastructure provides a diverse range of urban mobility.[181]

A total of 979 bridges cross 197 km (122 miles) the inner-city waterways. Berlin roads total 5,422 km (3,369 miles) of which 77 km (48 miles) are motorways (known as Autobahn).[182] The AVUS was the first automobile-only road[183] and served as an inspiration for the first motorways in the world.[184][185] In 2013 only 1.344 million motor vehicles were registered in the city.[182] With 377 cars per 1000 residents in 2013 (570/1000 in Germany), Berlin as a Western global city has one of the lowest numbers of cars per capita.[186]

Berlin is well known for its highly developed bicycle lane system.[187] It is estimated that Berlin has 710 bicycles per 1,000 residents. Around 500,000 daily bike riders accounted for 13 percent of total traffic in 2010.[188]

Cyclists in Berlin have access to 620 km of bicycle paths including approximately 150 km of mandatory bicycle paths, 190 km of off-road bicycle routes, 60 km of bicycle lanes on roads, 70 km of shared bus lanes which are also open to cyclists, 100 km of combined pedestrian/bike paths and 50 km of marked bicycle lanes on roadside pavements or sidewalks.[189] Riders are allowed to carry their bicycles on Regionalbahn (RE), S-Bahn and U-Bahn trains, on trams, and on night buses if a bike ticket is purchased.[190]

Taxicabs in Berlin are yellow or beige. In 2024, around 8,000 taxicabs were in service.[191] Like in most of Europe, app-based sharing cab services are available but limited.[192]

Long-distance rail lines directly connect Berlin with all of the major cities of Germany. the regional rail lines of the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg provide access to Brandenburg and to the Baltic Sea. The Berlin Hauptbahnhof (Berlin Central Station) is the largest grade-separated railway station in Europe.[193] The Deutsche Bahn runs the high speed Intercity-Express (ICE) to domestic destinations, including Hamburg, Munich, Cologne, Stuttgart, and Frankfurt am Main.

The Spree and the Havel rivers cross Berlin. There are no frequent passenger connections to and from Berlin by water. Berlin's largest harbour, the Westhafen, is located in the district of Moabit. It is a transhipment and storage site for inland shipping with a growing importance.[194]

There is an increasing quantity of intercity bus services. Berlin city has more than 10 stations[195] that run buses to destinations throughout Berlin. Destinations in Germany and Europe are connected via the intercity bus exchange Zentraler Omnibusbahnhof Berlin.

The Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) and the German State-owned Deutsche Bahn (DB) manage several extensive urban public transport systems.[196]

Public transport in Berlin has a long and complicated history because of the 20th-century division of the city, where movement between the two halves was not served. Since 1989, the transport network has been developed extensively. However, it still contains early 20th century traits, such as the U1.[197]

Berlin is served by one commercial international airport: Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER), located just outside Berlin's south-eastern border, in the state of Brandenburg. It began construction in 2006, with the intention of replacing Tegel Airport (TXL) and Schönefeld Airport (SXF) as the single commercial airport of Berlin.[198] Previously set to open in 2012, after extensive delays and cost overruns, it opened for commercial operations in October 2020.[199] The planned initial capacity of around 27 million passengers per year[200] is to be further developed to bring the terminal capacity to approximately 55 million per year by 2040.[201]

Before the opening of the BER in Brandenburg, Berlin was served by Tegel Airport and Schönefeld Airport. Tegel Airport was within the city limits, and Schönefeld Airport was located at the same site as BER. Both airports together handled 29.5 million passengers in 2015. In 2014, 67 airlines served 163 destinations in 50 countries from Berlin.[202] Tegel Airport was a focus city for Lufthansa and Eurowings while Schönefeld served as an important destination for airlines like Germania, easyJet and Ryanair. Until 2008, Berlin was also served by the smaller Tempelhof Airport, which functioned as a city airport, with a convenient location near the city center, allowing for quick transit times between the central business district and the airport. The airport grounds have since been turned into a city park.[citation needed]

From 1865 to 1976, Berlin operated an expansive pneumatic postal network, reaching a maximum length of 400 kilometers (roughly 250 miles) by 1940. The system was divided into two distinct networks after 1949. The West Berlin system remained in public use until 1963, and continued to be utilized for government correspondence until 1972. Conversely, the East Berlin system, which incorporated the Hauptelegraphenamt—the central hub of the operation—remained functional until 1976.[citation needed]

Berlin's two largest energy provider for private households are the Swedish firm Vattenfall and the Berlin-based company GASAG. Both offer electric power and natural gas supply. Some of the city's electric energy is imported from nearby power plants in southern Brandenburg.[203]

As of 2015[update] the five largest power plants measured by capacity are the Heizkraftwerk Reuter West, the Heizkraftwerk Lichterfelde, the Heizkraftwerk Mitte, the Heizkraftwerk Wilmersdorf, and the Heizkraftwerk Charlottenburg. All of these power stations generate electricity and useful heat at the same time to facilitate buffering during load peaks.

In 1993 the power grid connections in the Berlin-Brandenburg capital region were renewed. In most of the inner districts of Berlin power lines are underground cables; only a 380 kV and a 110 kV line, which run from Reuter substation to the urban Autobahn, use overhead lines. The Berlin 380-kV electric line is the backbone of the city's energy grid.

Berlin has a long history of discoveries in medicine and innovations in medical technology.[204] The modern history of medicine has been significantly influenced by scientists from Berlin. Rudolf Virchow was the founder of cellular pathology, while Robert Koch developed vaccines for anthrax, cholera, and tuberculosis.[205] For his life's work Koch is seen as one of the founders of modern medicine.[206]

The Charité complex (Universitätsklinik Charité) is the largest university hospital in Europe, tracing back its origins to the year 1710. More than half of all German Nobel Prize winners in Physiology or Medicine, including Emil von Behring, Robert Koch and Paul Ehrlich, have worked at the Charité. The Charité is spread over four campuses and comprises around 3,000 beds, 15,500 staff, 8,000 students, and more than 60 operating theaters, and it has a turnover of two billion euros annually.[207]

Since 2017, the digital television standard in Berlin and Germany is DVB-T2. This system transmits compressed digital audio, digital video and other data in an MPEG transport stream.

Berlin has installed several hundred free public Wireless LAN sites across the capital since 2016. The wireless networks are concentrated mostly in central districts; 650 hotspots (325 indoor and 325 outdoor access points) are installed.[208]

The UMTS (3G) and LTE (4G) networks of the three major cellular operators Vodafone, T-Mobile and O2 enable the use of mobile broadband applications citywide.

As of 2014[update], Berlin had 878 schools, teaching 340,658 students in 13,727 classes and 56,787 trainees in businesses and elsewhere.[150] The city has a 6-year primary education program. After completing primary school, students continue to the Sekundarschule (a comprehensive school) or Gymnasium (college preparatory school). Berlin has a special bilingual school program in the Europaschule, in which children are taught the curriculum in German and a foreign language, starting in primary school and continuing in high school.[210]

The Französisches Gymnasium Berlin, which was founded in 1689 to teach the children of Huguenot refugees, offers (German/French) instruction.[211] The John F. Kennedy School, a bilingual German–American public school in Zehlendorf, is particularly popular with children of diplomats and the English-speaking expatriate community. 82 Gymnasien teach Latin[212] and 8 teach Classical Greek.[213]

The Berlin-Brandenburg capital region is one of the most prolific centers of higher education and research in Germany and Europe. Historically, 67 Nobel Prize winners are affiliated with the Berlin-based universities.

The city has four public research universities and more than 30 private, professional, and technical colleges (Hochschulen), offering a wide range of disciplines.[214] A record number of 175,651 students were enrolled in the winter term of 2015/16.[215] Among them around 18% have an international background.

The three largest universities combined have approximately 103,000 enrolled students. There are the Freie Universität Berlin (Free University of Berlin, FU Berlin) with about 33,000[216] students, the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin (HU Berlin) with 35,000[217] students, and Technische Universität Berlin (TU Berlin) with 35,000[218] students. The Charité Medical School has around 8,000 students.[207] The FU, the HU, the TU, and the Charité make up the Berlin University Alliance, which has received funding from the Excellence Strategy program of the German government.[219][220] The Universität der Künste (UdK) has about 4,000 students and ESMT Berlin is only one of four business schools in Germany with triple accreditation.[221] The Hertie School, a private public policy school located in Mitte, has more than 900 students and doctoral students. The Berlin School of Economics and Law has an enrollment of about 11,000 students, the Berlin University of Applied Sciences and Technology of about 12,000 students, and the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft (University of Applied Sciences for Engineering and Economics) of about 14,000 students.

The city has a high density of internationally renowned research institutions, such as the Fraunhofer Society, the DLR Institute for Planetary Research, the Leibniz Association, the Helmholtz Association, and the Max Planck Society, which are independent of, or only loosely connected to its universities.[222] In 2012, around 65,000 professional scientists were working in research and development in the city.[150]

Berlin is one of the knowledge and innovation communities (KIC) of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT).[223] The KIC is based at the Center for Entrepreneurship at TU Berlin and has a focus in the development of IT industries. It partners with major multinational companies such as Siemens, Deutsche Telekom, and SAP.[224]

One of Europe's successful research, business and technology clusters is based at WISTA in Berlin-Adlershof, with more than 1,000 affiliated firms, university departments and scientific institutions.[225]

In addition to the university-affiliated libraries, the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin is a major research library. Its two main locations are on Potsdamer Straße and on Unter den Linden. There are also 86 public libraries in the city.[150] ResearchGate, a global social networking site for scientists, is based in Berlin.

.jpg/440px-Alte_Nationalgalerie_abends_(Zuschnitt).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Cafe_am_Holzmarkt,_River_Spree,_Berlin_(46636049685).jpg)

Berlin is known for its numerous cultural institutions, many of which enjoy international reputation.[27][226] The diversity and vivacity of the metropolis led to a trendsetting atmosphere.[227] An innovative music, dance and art scene has developed in the 21st century.

Young people, international artists and entrepreneurs continued to settle in the city and made Berlin a popular entertainment center in the world.[228]

The expanding cultural performance of the city was underscored by the relocation of the Universal Music Group who decided to move their headquarters to the banks of the River Spree.[229] In 2005, Berlin was named "City of Design" by UNESCO and has been part of the Creative Cities Network ever since.[230][24]

Many German and International films were shot in Berlin, including M, One, Two, Three, Cabaret, Christiane F., Possession, Octopussy, Wings of Desire, Run Lola Run, The Bourne Trilogy, Good Bye, Lenin!, The Lives of Others, Inglourious Basterds, Hanna, Unknown and Bridge of Spies.

As of 2011[update] Berlin is home to 138 museums and more than 400 art galleries.[150][231] The ensemble on the Museum Island is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is in the northern part of the Spree Island between the Spree and the Kupfergraben.[27] As early as 1841 it was designated a "district dedicated to art and antiquities" by a royal decree. Subsequently, the Altes Museum was built in the Lustgarten. The Neues Museum, which displays the bust of Queen Nefertiti,[232] Alte Nationalgalerie, Pergamon Museum, and Bode Museum were built there.

Apart from the Museum Island, there are many additional museums in the city. The Gemäldegalerie (Painting Gallery) focuses on the paintings of the "old masters" from the 13th to the 18th centuries, while the Neue Nationalgalerie (New National Gallery, built by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe) specializes in 20th-century European painting. The Hamburger Bahnhof, in Moabit, exhibits a major collection of modern and contemporary art. The expanded Deutsches Historisches Museum reopened in the Zeughaus with an overview of German history spanning more than a millennium. The Bauhaus Archive is a museum of 20th-century design from the famous Bauhaus school. Museum Berggruen houses the collection of noted 20th century collector Heinz Berggruen, and features an extensive assortment of works by Picasso, Matisse, Cézanne, and Giacometti, among others.[233] The Kupferstichkabinett Berlin (Museum of Prints and Drawings) is part of the Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin (Berlin State Museums) and the Kulturforum at Potsdamer Platz in the Tiergarten district of Berlin's Mitte district. It is the largest museum of the graphic arts in Germany and at the same time one of the four most important collections of its kind in the world.[234] The collection includes Friedrich Gilly's design for the monument to Frederick II of Prussia.[235]

The Jewish Museum has a standing exhibition on two millennia of German-Jewish history.[236] The German Museum of Technology in Kreuzberg has a large collection of historical technical artifacts. The Museum für Naturkunde (Berlin's natural history museum) exhibits natural history near Berlin Hauptbahnhof. It has the largest mounted dinosaur in the world (a Giraffatitan skeleton). A well-preserved specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex and the early bird Archaeopteryx are at display as well.[237]

In Dahlem, there are several museums of world art and culture, such as the Museum of Asian Art, the Ethnological Museum, the Museum of European Cultures, as well as the Allied Museum. The Brücke Museum features one of the largest collection of works by artist of the early 20th-century expressionist movement. In Lichtenberg, on the grounds of the former East German Ministry for State Security, is the Stasi Museum. The site of Checkpoint Charlie, one of the most renowned crossing points of the Berlin Wall, is still preserved. A private museum venture exhibits a comprehensive documentation of detailed plans and strategies devised by people who tried to flee from the East.

The Beate Uhse Erotic Museum claimed to be the largest erotic museum in the world until it closed in 2014.[238][239]

The cityscape of Berlin displays large quantities of urban street art.[240] It has become a significant part of the city's cultural heritage and has its roots in the graffiti scene of Kreuzberg of the 1980s.[241] The Berlin Wall itself has become one of the largest open-air canvasses in the world.[242] The leftover stretch along the Spree river in Friedrichshain remains as the East Side Gallery. Berlin today is consistently rated as an important world city for street art culture.[243]Berlin has galleries which are quite rich in contemporary art. Located in Mitte, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, KOW, Sprüth Magers; Kreuzberg there are a few galleries as well such as Blain Southern, Esther Schipper, Future Gallery, König Gallerie.

Berlin's nightlife has been celebrated as one of the most diverse and vibrant of its kind.[244][245] In the 1970s and 80s, the SO36 in Kreuzberg was a center for punk music and culture. The SOUND and the Dschungel gained notoriety. Throughout the 1990s, people in their 20s from all over the world, particularly those in Western and Central Europe, made Berlin's club scene a premier nightlife venue. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, many historic buildings in Mitte, the former city center of East Berlin, were illegally occupied and re-built by young squatters and became a fertile ground for underground and counterculture gatherings.[246] The central boroughs are home to many nightclubs, including the Watergate, Tresor and Berghain. The KitKatClub and several other locations are known for their sexually uninhibited parties.

Clubs are not required to close at a fixed time during the weekends, and many parties last well into the morning or even all weekend, including near Alexanderplatz. Several venues have become a popular stage for the Neo-Burlesque scene.

.jpg/440px-Hanukkah,_Brandenburg_Gate_(Berlin).jpg)

Berlin has a long history of gay culture, and is an important birthplace of the LGBT rights movement. Same-sex bars and dance halls operated freely as early as the 1880s, and the first gay magazine, Der Eigene, started in 1896. By the 1920s, gays and lesbians had an unprecedented visibility.[247][248] Today, in addition to a positive atmosphere in the wider club scene, the city again has a huge number of queer clubs and festivals. The most famous and largest are Berlin Pride, the Christopher Street Day,[249] the Lesbian and Gay City Festival in Berlin-Schöneberg, the Kreuzberg Pride.

The annual Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale) with around 500,000 admissions is considered to be the largest publicly attended film festival in the world.[250][251] The Karneval der Kulturen (Carnival of Cultures), a multi-ethnic street parade, is celebrated every Pentecost weekend.[252] Berlin is also well known for the cultural festival Berliner Festspiele, which includes the jazz festival JazzFest Berlin, and Young Euro Classic, the largest international festival of youth orchestras in the world. Several technology and media art festivals and conferences are held in the city, including Transmediale and Chaos Communication Congress. The annual Berlin Festival focuses on indie rock, electronic music and synthpop and is part of the International Berlin Music Week.[253][254] Every year Berlin hosts one of the largest New Year's Eve celebrations in the world, attended by well over a million people. The focal point is the Brandenburg Gate, where midnight fireworks are centered, but various private fireworks displays take place throughout the entire city. Partygoers in Germany often toast the New Year with a glass of sparkling wine.

Berlin is home to 44 theaters and stages.[150] The Deutsches Theater in Mitte was built in 1849–50 and has operated almost continuously since then. The Volksbühne at Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz was built in 1913–14, though the company had been founded in 1890. The Berliner Ensemble, famous for performing the works of Bertolt Brecht, was established in 1949. The Schaubühne was founded in 1962 and moved to the building of the former Universum Cinema on Kurfürstendamm in 1981. With a seating capacity of 1,895 and a stage floor of 2,854 square meters (30,720 sq ft), the Friedrichstadt-Palast in Berlin Mitte is the largest show palace in Europe. For Berlin's independent dance and theatre scene, venues such as the Sophiensäle in Mitte and the three houses of the Hebbel am Ufer (HAU) in Kreuzberg are important. Most productions there are also accessible to an English-speaking audience. Some of the dance and theatre groups that also work internationally (Gob Squad, Rimini Protokoll) are based there, as well as festivals such as the international festival Dance in August.

Berlin has three major opera houses: the Deutsche Oper, the Berlin State Opera, and the Komische Oper. The Berlin State Opera on Unter den Linden opened in 1742 and is the oldest of the three. Its musical director is Daniel Barenboim. The Komische Oper has traditionally specialized in operettas and is also at Unter den Linden. The Deutsche Oper opened in 1912 in Charlottenburg.

The city's main venue for musical theater performances are the Theater am Potsdamer Platz and Theater des Westens (built in 1895). Contemporary dance can be seen at the Radialsystem V. The Tempodrom is host to concerts and circus-inspired entertainment. It also houses a multi-sensory spa experience. The Admiralspalast in Mitte has a vibrant program of variety and music events.

There are seven symphony orchestras in Berlin. The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world;[255] it is housed in the Berliner Philharmonie near Potsdamer Platz on a street named for the orchestra's longest-serving conductor, Herbert von Karajan.[256] Simon Rattle was its principal conductor from 1999 to 2018, a position now held by Kirill Petrenko. The Konzerthausorchester Berlin was founded in 1952 as the orchestra for East Berlin. Christoph Eschenbach is its principal conductor. The Haus der Kulturen der Welt presents exhibitions dealing with intercultural issues and stages world music and conferences.[257] The Kookaburra and the Quatsch Comedy Club are known for satire and comedy shows. In 2018, the New York Times described Berlin as "arguably the world capital of underground electronic music".[258]

The cuisine and culinary offerings of Berlin vary greatly. 23 restaurants in Berlin have been awarded one or more Michelin stars in the Michelin Guide of 2021, which ranks the city at the top for the number of restaurants having this distinction in Germany.[259] Berlin is well known for its offerings of vegetarian[260] and vegan[261] cuisine and is home to an innovative entrepreneurial food scene promoting cosmopolitan flavors, local and sustainable ingredients, pop-up street food markets, supper clubs, as well as food festivals, such as Berlin Food Week.[262][263]

Many local foods originated from north German culinary traditions and include rustic and hearty dishes with pork, goose, fish, peas, beans, cucumbers, or potatoes. Typical Berliner fare include popular street food like the Currywurst (which gained popularity with postwar construction workers rebuilding the city), Buletten and the Berliner donut, known in Berlin as Pfannkuchen (German: [ˈp͡fanˌkuːxn̩] ).[264][265] German bakeries offering a variety of breads and pastries are widespread. One of Europe's largest delicatessen markets is found at the KaDeWe, and among the world's largest chocolate stores is Rausch.[266][267]

Berlin is also home to a diverse gastronomy scene reflecting the immigrant history of the city. Turkish and Arab immigrants brought their culinary traditions to the city, such as the lahmajoun and falafel, which have become common fast food staples. The modern fast-food version of the doner kebab sandwich which evolved in Berlin in the 1970s, has since become a favorite dish in Germany and elsewhere in the world.[268] Asian cuisine like Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, Indian, Korean, and Japanese restaurants, as well as Spanish tapas bars, Italian, and Greek cuisine, can be found in many parts of the city.

Zoologischer Garten Berlin, the older of two zoos in the city, was founded in 1844. It is the most visited zoo in Europe and presents the most diverse range of species in the world.[269] It was the home of the captive-born celebrity polar bear Knut.[270] The city's other zoo, Tierpark Friedrichsfelde, was founded in 1955.

Berlin's Botanischer Garten includes the Botanic Museum Berlin. With an area of 43 hectares (110 acres) and around 22,000 different plant species, it is one of the largest and most diverse collections of botanical life in the world. Other gardens in the city include the Britzer Garten, and the Gärten der Welt (Gardens of the World) in Marzahn.[271]

The Tiergarten park in Mitte, with landscape design by Peter Joseph Lenné, is one of Berlin's largest and most popular parks.[272] In Kreuzberg, the Viktoriapark provides a viewing point over the southern part of inner-city Berlin. Treptower Park, beside the Spree in Treptow, features a large Soviet War Memorial. The Volkspark in Friedrichshain, which opened in 1848, is the oldest park in the city, with monuments, a summer outdoor cinema and several sports areas.[273] Tempelhofer Feld, the site of the former city airport, is the world's largest inner-city open space.[274]

Potsdam is on the southwestern periphery of Berlin. The city was a residence of the Prussian kings and the German Kaiser, until 1918. The area around Potsdam in particular Sanssouci is known for a series of interconnected lakes and cultural landmarks. The Palaces and Parks of Potsdam and Berlin are the largest World Heritage Site in Germany.[226]

Berlin is also well known for its numerous cafés, street musicians, beach bars along the Spree River, flea markets, boutique shops and pop-up stores, which are a source for recreation and leisure.[275]

Berlin has established a high-profile as a host city of major international sporting events.[276] The city hosted the 1936 Summer Olympics and was the host city for the 2006 FIFA World Cup final.[277] The World Athletics Championships was held at Olympiastadion in 2009 and 2025.[278] The city hosted the Euroleague Final Four basketball competition in 2009 and 2016,[279] and was one of the hosts of FIBA EuroBasket 2015. In 2015 Berlin was the venue for the UEFA Champions League Final. The city bid to host the 2000 Summer Olympics but lost to Sydney.[280]

Berlin hosted the 2023 Special Olympics World Summer Games. This is the first time Germany has ever hosted the Special Olympics World Games.[281]

The annual Berlin Marathon – a course that holds the most top-10 world record runs – and the ISTAF are well-established athletic events in the city.[282] The Mellowpark in Köpenick is one of the biggest skate and BMX parks in Europe.[283] A fan fest at Brandenburg Gate, which attracts several hundreds of thousands of spectators, has become popular during international football competitions, such as the UEFA European Championship.[284]

Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, who is often hailed as the "father of modern gymnastics", invented the horizontal bar, parallel bars, rings, and the vault around 1811 in Berlin.[285][286][287] Jahn's Turners movement, first realized at Volkspark Hasenheide, was the origin of modern sports clubs.[288] In 2013, around 600,000 Berliners were registered in one of the more than 2,300 sport and fitness clubs.[289] The city of Berlin operates more than 60 public indoor and outdoor swimming pools.[290] Berlin is the largest Olympic training center in Germany, with around 500 top athletes (15% of all German top athletes) being based there. Forty-seven elite athletes participated in the 2012 Summer Olympics. Berliners would achieve seven gold, twelve silver, and three bronze medals.[291]