Ревущие двадцатые , иногда стилизованные как Ревущие двадцатые , относятся к десятилетию 1920-х годов в музыке и моде, как это произошло в западном обществе и западной культуре . Это был период экономического процветания с отличительным культурным краем в Соединенных Штатах и Европе, особенно в таких крупных городах, как Берлин, [1] Буэнос-Айрес, [2] [3] Чикаго, [4] Лондон, [5] Лос-Анджелес, [6] Мехико, [3] Нью-Йорк, [7] Париж, [8] и Сидней. [9] Во Франции десятилетие было известно как années folles ( ' сумасшедшие годы ' ), [10] подчеркивая социальный, художественный и культурный динамизм эпохи. Джаз расцвел, флэппер переопределил современный облик британских и американских женщин, [11] [12] и ар-деко достигло пика. [13]

Социальные и культурные особенности, известные как Ревущие двадцатые, начались в ведущих столичных центрах и широко распространились после Первой мировой войны . Дух Ревущих двадцатых был отмечен общим чувством новизны, связанным с современностью и разрывом с традициями, посредством современных технологий, таких как автомобили, движущиеся изображения и радио, приносящих «современность» большой части населения. Формальные декоративные излишества были отброшены в пользу практичности как в повседневной жизни, так и в архитектуре. В то же время джаз и танцы стали более популярными, в противовес настроениям Первой мировой войны. Таким образом, этот период часто называют Эпохой джаза .

В 1920-х годах наблюдалось широкомасштабное развитие и использование автомобилей, телефонов, фильмов, радио и электроприборов в жизни миллионов людей в западном мире. Авиация вскоре стала бизнесом из-за своего быстрого роста. Страны увидели быстрый промышленный и экономический рост, ускорили потребительский спрос и ввели значительные новые тенденции в образе жизни и культуре. Средства массовой информации, финансируемые новой индустрией массовой рекламы, стимулирующей потребительский спрос, сосредоточились на знаменитостях, особенно на героях спорта и кинозвездах, поскольку города болели за свои домашние команды и заполняли новые дворцовые кинотеатры и гигантские спортивные стадионы. Во многих странах женщины получили право голоса .

Уолл-стрит вложила значительные средства в Германию в рамках Плана Дауэса 1924 года , названного в честь банкира и позднее 30-го вице-президента Чарльза Г. Доуса . Деньги были использованы косвенно для выплаты репараций странам, которые также должны были выплачивать свои военные долги Вашингтону. [14] Хотя к середине десятилетия процветание было широко распространено, а вторая половина десятилетия была известна, особенно в Германии, как « Золотые двадцатые », [15] десятилетие быстро подходило к концу. Крах Уолл-стрит 1929 года завершил эпоху, поскольку Великая депрессия принесла годы лишений по всему миру. [16]

Бурные двадцатые были десятилетием экономического роста и всеобщего процветания, обусловленного восстановлением после военной разрухи и отложенных расходов, бумом строительства и быстрым ростом потребительских товаров, таких как автомобили и электричество в Северной Америке и Европе, а также в нескольких других развитых странах, таких как Австралия. [18] Экономика Соединенных Штатов, успешно перешедшая от экономики военного времени к экономике мирного времени, процветала и предоставляла кредиты для европейского бума. Некоторые секторы стагнировали , особенно сельское хозяйство и добыча угля. США стали самой богатой страной в мире на душу населения и с конца 19 века были крупнейшей по общему ВВП. Ее промышленность была основана на массовом производстве , а ее общество аккультурировалось в потребительстве . Европейские экономики , напротив, пережили более сложную послевоенную перестройку и не начали процветать до примерно 1924 года. [19]

Сначала прекращение производства военного времени вызвало кратковременную, но глубокую рецессию, рецессию после Первой мировой войны 1919–1920 годов и резкую дефляционную рецессию или депрессию в 1920–1921 годах. Однако экономики США и Канады быстро восстановились, поскольку вернувшиеся солдаты снова влились в рабочую силу, а военные заводы были переоборудованы для производства потребительских товаров.

Массовое производство сделало технологии доступными для среднего класса. [19] Автомобильная промышленность , киноиндустрия , радиопромышленность и химическая промышленность взлетели в 1920-х годах.

До Первой мировой войны автомобили были предметом роскоши . В 1920-х годах массовое производство автомобилей стало обычным явлением в США и Канаде. К 1927 году Ford Motor Company прекратила выпуск Ford Model T после продажи 15 миллионов единиц этой модели. Она находилась в непрерывном производстве с октября 1908 года по май 1927 года. [20] [21] Компания планировала заменить старую модель более новой, Ford Model A. [ 22] Это решение было реакцией на конкуренцию. Благодаря коммерческому успеху Model T, Ford доминировал на автомобильном рынке с середины 1910-х до начала 1920-х годов. В середине 1920-х годов доминирование Ford ослабло, поскольку его конкуренты догнали систему массового производства Ford. Они начали превосходить Ford в некоторых областях, предлагая модели с более мощными двигателями, новыми удобными функциями и стилем. [23] [24] [25]

В 1918 году во всей Канаде было зарегистрировано всего около 300 000 транспортных средств, но к 1929 году их было 1,9 миллиона. К 1929 году в Соединенных Штатах было зарегистрировано чуть менее 27 000 000 [26] автотранспортных средств. Автомобильные детали производились в Онтарио, недалеко от Детройта, штат Мичиган. Влияние автомобильной промышленности на другие сегменты экономики было широко распространено, давая толчок таким отраслям, как производство стали, строительство автомагистралей, мотелей, станций техобслуживания, автосалонов и нового жилья за пределами городского ядра.

Ford открыл заводы по всему миру и доказал, что является сильным конкурентом на большинстве рынков для своих недорогих, простых в обслуживании автомобилей. General Motors , в меньшей степени, последовала за ним. Европейские конкуренты избегали рынка с низкими ценами и концентрировались на более дорогих автомобилях для состоятельных потребителей. [27]

Радио стало первым средством массового вещания . Радио были дорогими, но их способ развлечения оказался революционным. Реклама на радио стала платформой для массового маркетинга . Ее экономическое значение привело к массовой культуре , которая доминировала в обществе с этого периода. Во время « Золотого века радио » радиопрограммы были такими же разнообразными, как и телевизионные программы 21-го века. Создание в 1927 году Федеральной радиокомиссии открыло новую эру регулирования.

В 1925 году электрическая запись , одно из величайших достижений в области звукозаписи , стала доступна с появлением коммерческих граммофонных пластинок .

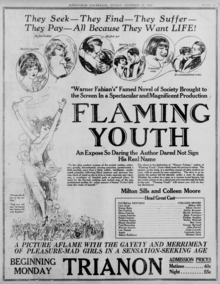

Кино процветало, создавая новую форму развлечений, которая фактически положила конец старому театральному жанру водевиля . Просмотр фильма был дешевым и доступным; толпы людей устремились в новые кинотеатры в центре города и районные театры. С начала 1910-х годов более дешевое кино успешно конкурировало с водевилем. Многие исполнители водевиля и другие театральные деятели были наняты киноиндустрией, привлеченные более высокими зарплатами и менее тяжелыми условиями труда. Введение звукового кино , также известного как «говорящее кино», которое не было на подъеме до конца десятилетия 1920-х годов, устранило последнее главное преимущество водевиля и привело его к резкому финансовому упадку. Престижная сеть театров водевиля и кинотеатров Orpheum Circuit была поглощена новой киностудией. [28]

В 1923 году изобретатель Ли де Форест из Phonofilm выпустил несколько короткометражных фильмов со звуком. Тем временем изобретатель Теодор Кейс разработал звуковую систему Movietone и продал права на нее киностудии Fox Film . В 1926 году была представлена звуковая система Vitaphone . Художественный фильм Don Juan (1926) стал первым полнометражным фильмом, в котором использовалась звуковая система Vitaphone с синхронизированной музыкальной партитурой и звуковыми эффектами, хотя в нем не было разговорных диалогов. [29] Фильм был выпущен киностудией Warner Bros. В октябре 1927 года звуковой фильм The Jazz Singer (1927) оказался кассовым успехом. Он был новаторским благодаря использованию звука. Произведенный с помощью системы Vitaphone, большая часть фильма не содержит живого звука, полагаясь на партитуру и эффекты. Однако когда звезда фильма, Эл Джолсон , поет, фильм переключается на звук, записанный на съемочной площадке, включая как его музыкальные выступления, так и две сцены с импровизированной речью — в одной персонаж Джолсона, Джеки Рабинович (Джек Робин), обращается к зрителям кабаре; в другой — его разговор с матерью. Также были слышны «естественные» звуки декораций. [30] Прибыль от фильма стала для киноиндустрии достаточным доказательством того, что в эту технологию стоило инвестировать. [31]

В 1928 году киностудии Famous Players–Lasky (позже известная как Paramount Pictures ), First National Pictures , Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer и Universal Studios подписали соглашение с Electrical Research Products Inc. (ERPI) о переоборудовании производственных мощностей и театров для звукового кино. Первоначально все кинотеатры с проводами ERPI были совместимы с Vitaphone; большинство из них также были оборудованы для проецирования катушек Movietone. [32] Также в 1928 году Radio Corporation of America (RCA) выпустила на рынок новую звуковую систему — систему RCA Photophone . RCA предложила права на свою систему дочерней компании RKO Pictures . Warner Bros. продолжила выпускать несколько фильмов с живыми диалогами, хотя и только в нескольких сценах. Наконец, она выпустила « Огни Нью-Йорка» (1928), первый полностью говорящий полнометражный художественный фильм. Анимационный короткометражный фильм « Время ужина » (1928) студии Van Beuren Studios был одним из первых анимационных звуковых фильмов. За ним несколько месяцев спустя последовал анимационный короткометражный фильм «Пароходик Вилли» (1928), первый звуковой фильм студии Walt Disney Animation Studios . Это был первый коммерчески успешный анимационный короткометражный фильм, в котором появился персонаж Микки Маус . [33] «Пароходик Вилли» был первым мультфильмом, в котором использовалась полностью пост-продакшн-саундтрек, что отличало его от более ранних звуковых мультфильмов. Он стал самым популярным мультфильмом своего времени. [34]

На протяжении большей части 1928 года Warner Bros. была единственной студией, которая выпускала говорящие фильмы . Она получала прибыль от своих инновационных фильмов в прокате. Другие студии ускорили темпы своего перехода на новую технологию и начали производить собственные звуковые и говорящие фильмы. В феврале 1929 года, через шестнадцать месяцев после «Певца джаза» , Columbia Pictures стала восьмой и последней крупной студией, выпустившей говорящий фильм. В мае 1929 года Warner Bros. выпустила « На шоу!» (1929), первый полностью цветной, полностью говорящий художественный фильм. [35] Вскоре производство немого кино прекратилось. Последним полностью немым фильмом, выпущенным в США для общего проката, был «Бедный миллионер» , выпущенный Biltmore Pictures в апреле 1930 года. Четыре других немых фильма, все малобюджетные вестерны , также были выпущены в начале 1930 года. [36]

1920-е годы стали эпохальными событиями в авиации, которые привлекли внимание всего мира. В 1927 году Чарльз Линдберг прославился первым в истории одиночным беспосадочным трансатлантическим перелетом . Он вылетел с аэродрома Рузвельт-Филд в Нью-Йорке и приземлился в аэропорту Париж-Ле-Бурже . Линдбергу потребовалось 33,5 часа, чтобы пересечь Атлантический океан. [37] Его самолет, Spirit of St. Louis , был изготовленным на заказ одномоторным одноместным монопланом . Он был спроектирован авиационным инженером Дональдом А. Холлом . В Великобритании Эми Джонсон (1903–1941) была первой женщиной, которая в одиночку перелетела из Великобритании в Австралию. Летая в одиночку или со своим мужем Джимом Моллисоном, она установила множество рекордов на большие расстояния в 1930-х годах. [38]

В 1920-х годах несколько изобретателей продвинули работу над телевидением, но программы стали доступны широкой публике только накануне Второй мировой войны, и лишь немногие люди вообще видели телевизор до середины 1940-х годов.

В июле 1928 года Джон Лоуги Бэрд продемонстрировал первую в мире цветную передачу, используя сканирующие диски на передающем и приемном концах с тремя спиралями отверстий, каждая спираль с фильтром разного основного цвета; и три источника света на приемном конце с коммутатором для чередования их освещения. [39] В том же году он также продемонстрировал стереоскопическое телевидение. [40]

В 1927 году Бэрд передал телевизионный сигнал на расстояние в 438 миль (705 км) по телефонной линии между Лондоном и Глазго; Бэрд передал первые в мире телевизионные изображения на расстояние в Central Hotel на Центральном вокзале Глазго. [41] Затем Бэрд основал Baird Television Development Company Ltd и в 1928 году осуществил первую трансатлантическую телевизионную передачу из Лондона в Хартсдейл, штат Нью-Йорк, а также первую телевизионную программу для BBC. [42]

Биологи десятилетиями работали над лекарством, которое стало пенициллином. В 1928 году шотландский биолог Александр Флеминг открыл вещество, которое убивало ряд болезнетворных бактерий. В 1929 году он назвал новое вещество пенициллином . Его публикации поначалу в значительной степени игнорировались, но в 1930-х годах оно стало значимым антибиотиком . В 1930 году Сесил Джордж Пейн, патолог из Шеффилдского королевского госпиталя , использовал пенициллин для лечения сикоза бороды , высыпаний в фолликулах бороды, но безуспешно. Перейдя к офтальмии новорожденных , гонококковой инфекции у младенцев, он добился первого зарегистрированного излечения пенициллином 25 ноября 1930 года. Затем он вылечил еще четырех пациентов (одного взрослого и трех младенцев) от глазных инфекций, но не смог вылечить пятого. [43] [44] [45]

Доминирование автомобиля привело к появлению новой психологии, восхваляющей мобильность. [46] Легковые и грузовые автомобили нуждались в строительстве дорог, новых мостах и регулярном обслуживании автомагистралей, в значительной степени финансируемом местными и государственными органами власти за счет налогов на бензин. Фермеры были первыми, кто использовал свои пикапы для перевозки людей, грузов и животных. Возникли новые отрасли промышленности — для производства шин и стекла, очистки топлива, а также для обслуживания и ремонта миллионов автомобилей и грузовиков. Новые автодилеры получили франшизу от автопроизводителей и стали основными двигателями в местном деловом сообществе. Туризм получил огромный импульс, с появлением отелей, ресторанов и сувенирных магазинов. [47] [48]

Электрификация , замедлившаяся во время войны, значительно продвинулась вперед по мере того, как все больше США и Канады присоединялись к электросети . Промышленность перешла с угля на электричество. В то же время были построены новые электростанции . В Америке производство электроэнергии почти увеличилось в четыре раза. [49]

Телефонные линии также протягивались по всему континенту. Впервые во многих домах была установлена внутренняя сантехника, что стало возможным благодаря современным канализационным системам .

Урбанизация достигла рубежа в переписи 1920 года, результаты которой показали, что немного больше американцев проживало в городских районах, поселках и городах с населением 2500 или более человек, чем в небольших городах или сельской местности. Однако нация была очарована своими крупными столичными центрами, в которых проживало около 15% населения. Города Нью-Йорк и Чикаго соперничали в строительстве небоскребов, а Нью-Йорк вырвался вперед со своим Эмпайр-стейт-билдинг . Основная модель современной работы «белых воротничков» была установлена в конце 19 века, но теперь она стала нормой для жизни в крупных и средних городах. Пишущие машинки, картотечные шкафы и телефоны привели многих незамужних женщин на канцелярские должности. В Канаде к концу десятилетия каждый пятый работник был женщиной. Интерес к поиску работы в постоянно растущем производственном секторе городов США стал широко распространенным среди сельских американцев. [50]

Многие страны расширили избирательные права женщин, такие как США, Канада, Великобритания, Индия и различные европейские страны в 1917–1921 годах. Это повлияло на многие правительства и выборы, увеличив число избирателей (но не удвоив его, поскольку многие женщины не голосовали в первые годы избирательного права, о чем свидетельствует большое падение явки избирателей). Политики отреагировали, сосредоточившись больше на вопросах, волнующих женщин, особенно на мире, здравоохранении, образовании и статусе детей. В целом женщины голосовали так же, как и мужчины, за исключением того, что их больше интересовал мир, [51] [52] [53] даже когда это означало умиротворение. [54]

«Потерянное поколение» состояло из молодых людей, которые вышли из Первой мировой войны разочарованными и циничными по отношению к миру. Термин обычно относится конкретно к американским литературным знаменитостям, которые жили в Париже в то время. Известными членами были Эрнест Хемингуэй , Ф. Скотт Фицджеральд и Гертруда Стайн , которые писали романы и рассказы, критикуя материализм, который, по их мнению, процветал в эту эпоху.

В Соединенном Королевстве яркими молодыми людьми были молодые аристократы и светские львицы, которые устраивали костюмированные вечеринки, отправлялись на сложные поиски сокровищ, их видели во всех модных заведениях и о них много писали в колонках светской хроники лондонских таблоидов. [55]

Поскольку среднестатистический американец в 1920-х годах все больше увлекался богатством и повседневной роскошью, некоторые начали высмеивать лицемерие и жадность, которые они наблюдали. Из этих социальных критиков Синклер Льюис был самым популярным. Его популярный роман 1920 года «Главная улица» высмеивал скучную и невежественную жизнь жителей городка на Среднем Западе. Затем он написал «Бэббит» о бизнесмене средних лет , который восстает против своей скучной жизни и семьи, только чтобы понять, что молодое поколение так же лицемерно, как и его собственное. Льюис высмеивал религию в «Элмере Гантри» , в котором рассказывалось о мошеннике , который объединяется с евангелистом, чтобы продать религию небольшому городку.

Другие социальные критики включали Шервуда Андерсона , Эдит Уортон и Х. Л. Менкена . Андерсон опубликовал сборник рассказов под названием «Уайнсбург, Огайо» , в котором изучал динамику небольшого города. Уортон высмеивала моду новой эпохи в своих романах, таких как « Сумеречный сон» (1927). Менкен критиковал узкие американские вкусы и культуру в эссе и статьях.

Ар-деко — стиль дизайна и архитектуры, ознаменовавший эту эпоху. Возникнув в Европе, он распространился на остальную часть Западной Европы и Северной Америки к середине 1920-х годов.

В США одно из самых замечательных зданий, выполненных в этом стиле, было построено как самое высокое здание того времени: Крайслер-билдинг . Формы ар-деко были чистыми и геометрическими, хотя художники часто черпали вдохновение в природе. Вначале линии были изогнутыми, хотя прямолинейные конструкции позже стали становиться все более и более популярными.

Живопись в Северной Америке в 1920-е годы развивалась в ином направлении, чем в Европе. В Европе 1920-е годы были эпохой экспрессионизма и позднее сюрреализма . Как заявил Ман Рэй в 1920 году после публикации уникального выпуска New York Dada : « Дада не может жить в Нью-Йорке».

В начале десятилетия фильмы были немыми и бесцветными. В 1922 году вышел первый полностью цветной фильм «Плата за море ». В 1926 году Warner Bros. выпустила «Дон Жуана» , первый фильм со звуковыми эффектами и музыкой. В 1927 году Warner выпустила «Певца джаза» , первый звуковой фильм, включающий ограниченные разговорные эпизоды.

Публика сходила с ума от звуковых фильмов, и киностудии перешли на звук практически в одночасье. [56] В 1928 году Warner выпустила «Огни Нью-Йорка» , первый полностью говорящий художественный фильм. В том же году был выпущен первый звуковой мультфильм « Время ужина» . Warner завершила десятилетие, представив в 1929 году «На шоу» — первый полностью цветной, полностью говорящий художественный фильм.

В то время в кинотеатрах были популярны короткометражные мультфильмы. В конце 1920-х годов появился Уолт Дисней . Микки Маус дебютировал в «Пароходике Вилли» 18 ноября 1928 года в театре Colony в Нью-Йорке. Микки был показан в более чем 120 короткометражных мультфильмах, « Клубе Микки Мауса» и других специальных выпусках. Это положило начало Disney и привело к созданию других персонажей в 1930-х годах. [57] Освальд Счастливый Кролик , персонаж, созданный Disney до Микки в 1927 году, был заключен контракт с Universal для целей распространения и снялся в серии короткометражек между 1927 и 1928 годами. Disney потерял права на персонажа, но в 2006 году вернул себе права на Освальда. Он был первым персонажем Disney, который был продан. [58]

В этот период появились такие кассовые звёзды, как Мэй Мюррей , Рамон Новарро , Рудольф Валентино , Бастер Китон , Гарольд Ллойд , Уорнер Бакстер , Клара Боу , Луиза Брукс , Бэби Пегги , Беби Дэниелс , Билли Дав , Дороти Маккэйл , Мэри Астор , Нэнси Кэрролл , Джанет Гейнор , Чарльз Фаррелл , Уильям Хейнс , Конрад Нагель , Джон Гилберт , Грета Гарбо , Долорес дель Рио , Норма Талмадж , Коллин Мур , Нита Нальди , Литрис Джой , Джон Бэрримор , Норма Ширер , Джоан Кроуфорд , Анна Мэй Вонг и Эл Джолсон . [59]

Афроамериканская литературная и художественная культура быстро развивалась в 1920-х годах под знаменем « Harlem Renaissance ». В 1921 году была основана Black Swan Corporation . На пике своего развития она выпускала 10 записей в месяц. В 1921 году также начались мюзиклы, полностью посвященные афроамериканцам. В 1923 году Боб Дуглас основал баскетбольный клуб Harlem Renaissance . В конце 1920-х годов, и особенно в 1930-х годах, баскетбольная команда стала известна как лучшая в мире.

Вышел в свет первый выпуск журнала Opportunity . Афроамериканский драматург Уиллис Ричардсон дебютировал со своей пьесой The Chip Woman's Fortune в театре Frazee Theatre (также известном как театр Wallacks ). [1] Известные афроамериканские авторы, такие как Лэнгстон Хьюз и Зора Нил Херстон, начали добиваться уровня национального общественного признания в 1920-х годах.

1920-е годы принесли новые стили музыки в русло культуры в авангардных городах. Джаз стал самой популярной формой музыки для молодежи. [60] Историк Кэти Дж. Огрен писала, что к 1920-м годам джаз стал «доминирующим влиянием на популярную музыку Америки в целом» [61] Скотт Дево утверждает, что сложилась стандартная история джаза, такая что: «После обязательного поклона африканским корням и регтаймовым предшественникам, музыка показана движущейся через последовательность стилей или периодов: джаз Нового Орлеана в 1920-х годах, свинг в 1930-х годах, бибоп в 1940-х годах, кул-джаз и хард-боп в 1950-х годах, фри-джаз и фьюжн в 1960-х годах.... Существует существенное согласие относительно определяющих черт каждого стиля, пантеона великих новаторов и канона записанных шедевров». [62]

Пантеон исполнителей и певцов 1920-х годов включает Луи Армстронга , Дюка Эллингтона , Сидни Беше , Джелли Ролл Мортона , Джо «Кинга» Оливера , Джеймса П. Джонсона , Флетчера Хендерсона , Фрэнки Трамбауэра , Пола Уайтмена , Роджера Вулфа Кана , Бикса Бейдербека , Аделаиду Холл и Бинга Кросби . Развитие городского и городского блюза также началось в 1920-х годах с такими исполнителями, как Бесси Смит и Ма Рейни . Во второй половине десятилетия ранние формы кантри-музыки были пионерами Джимми Роджерса , The Carter Family , Uncle Dave Macon , Вернона Далхарта и Чарли Пула . [63]

Танцевальные клубы стали чрезвычайно популярны в 1920-х годах. Их популярность достигла пика в конце 1920-х годов и продлилась до начала 1930-х годов. Танцевальная музыка стала доминировать во всех формах популярной музыки к концу 1920-х годов. Классические произведения, оперетты, народная музыка и т. д. были преобразованы в популярные танцевальные мелодии, чтобы удовлетворить помешательство публики на танцах. Например, многие песни из музыкальной оперетты Technicolor 1929 года " The Rogue Song " (в главной роли звезда Метрополитен-опера Лоуренс Тиббетт ) были переработаны и выпущены как танцевальная музыка и стали популярными хитами танцевальных клубов в 1929 году.

Танцевальные клубы по всему США спонсировали танцевальные конкурсы, где танцоры придумывали, пробовали и соревновались с новыми движениями. Профессионалы начали оттачивать свое мастерство в степе и других танцах той эпохи по всей сцене Соединенных Штатов. С появлением говорящего кино (звукового кино) мюзиклы стали последним писком моды, и киностудии наводнили кассы экстравагантными и роскошными музыкальными фильмами. Представитель был мюзиклом « Золотоискатели Бродвея» , который стал самым кассовым фильмом десятилетия. Гарлем сыграл ключевую роль в развитии танцевальных стилей. Несколько развлекательных заведений привлекали людей всех рас. В Cotton Club выступали чернокожие исполнители, и он обслуживал белую клиентуру, в то время как Savoy Ballroom обслуживал в основном черную клиентуру. Некоторые религиозные моралисты проповедовали против «Сатаны в танцевальном зале», но не имели большого влияния. [64]

Самыми популярными танцами на протяжении десятилетия были фокстрот , вальс и американское танго . Однако с начала 1920-х годов было разработано множество эксцентричных новых танцев. Первыми из них были Breakaway и Charleston . Оба были основаны на афроамериканских музыкальных стилях и ритмах, включая широко популярный блюз . Популярность Charleston взорвалась после его появления в двух бродвейских шоу 1922 года. Кратковременное увлечение Black Bottom , зародившееся в Apollo Theater , охватило танцевальные залы с 1926 по 1927 год, заменив Charleston по популярности. [65] К 1927 году Lindy Hop , танец, основанный на Breakaway и Charleston и объединяющий элементы степа, стал доминирующим социальным танцем . Разработанный в Savoy Ballroom, он был настроен на то, чтобы шагнуть вперед под фортепианный регтайм -джаз. Позже Lindy Hop превратился в другие танцы Swing . [66] Тем не менее, эти танцы так и не стали мейнстримом, и подавляющее большинство людей в Западной Европе и США продолжали танцевать фокстрот, вальс и танго на протяжении всего десятилетия. [67]

Увлечение танцами оказало большое влияние на популярную музыку. Было выпущено большое количество записей, обозначенных как фокстрот, танго и вальс, что дало начало поколению исполнителей, которые стали известны как записывающиеся артисты или радиоартисты. Среди лучших вокалистов были Ник Лукас , Аделаида Холл , Скраппи Ламберт , Фрэнк Манн, Льюис Джеймс , Честер Гейлорд , Джин Остин , Джеймс Мелтон , Франклин Баур , Джонни Марвин, Аннетт Хэншоу , Хелен Кейн , Вон Де Лит и Рут Эттинг . Среди ведущих руководителей танцевальных оркестров были Боб Харинг , Гарри Хорлик , Луис Кацман, Лео Рейсман , Виктор Арден , Фил Оман , Джордж Олсен , Тед Льюис , Эйб Лайман , Бен Селвин , Нат Шилкрет , Фред Уоринг и Пол Уайтмен . [68]

Париж задал модные тенденции для Европы и Северной Америки. [69] Мода для женщин была направлена на то, чтобы быть свободными. Женщины носили платья весь день, каждый день. Дневные платья имели заниженную талию, которая представляла собой пояс или ремень вокруг низкой талии или бедра, и юбку, которая свисала где угодно от щиколотки до колена, но никогда выше. Дневная одежда имела рукава (длинные до середины бицепса) и юбку, которая была прямой, плиссированной, с кулиской или уставшей. Украшения были менее заметны. [70] Волосы часто подстригались, что придавало мальчишеский вид. [71]

Для мужчин, работающих в белых воротничках, деловые костюмы были повседневной одеждой. Полосатые, клетчатые или оконные костюмы были темно-серыми, синими и коричневыми зимой и цвета слоновой кости, белого, коричневого и пастельных тонов летом. Рубашки были белыми, а галстуки были обязательными. [72]

Увековеченная в фильмах и на обложках журналов, мода молодых женщин 1920-х годов задала и тренд, и социальное заявление, разрыв с жестким викторианским образом жизни. Эти молодые, мятежные женщины среднего класса, которых старшие поколения называли «флэпперами», отказались от корсета и надели облегающие платья длиной до колен, которые обнажали их ноги и руки. Прической десятилетия был боб длиной до подбородка, имевший несколько популярных вариаций. Косметика, которая до 1920-х годов обычно не принималась в американском обществе из-за ее ассоциации с проституцией, стала чрезвычайно популярной. [73]

В 1920-х годах новые журналы привлекали молодых немецких женщин чувственным образом и рекламой подходящей одежды и аксессуаров, которые они хотели бы приобрести. Глянцевые страницы Die Dame и Das Blatt der Hausfrau демонстрировали «Neue Frauen», «Новую девушку» — то, что американцы называли флэппером . Она была молода и модна, финансово независима и была жадной потребительницей последних модных тенденций. Журналы держали ее в курсе стилей, одежды, дизайнеров, искусства, спорта и современных технологий, таких как автомобили и телефоны. [74]

1920-е годы были периодом социальной революции, последовавшей за Первой мировой войной, общество изменилось, поскольку запреты исчезли, и молодежь потребовала новых впечатлений и большей свободы от старого контроля. Сопровождающие утратили свою значимость, поскольку лозунгом для молодежи, берущей под контроль свою субкультуру, стало «все дозволено». [75] Родилась новая женщина — «флэппер», которая танцевала, пила, курила и голосовала. Эта новая женщина стригла волосы, пользовалась косметикой и тусовалась. Она была известна своей легкомысленностью и готовностью рисковать. [76] Женщины получили право голоса в большинстве стран. Для одиноких женщин открылись новые карьеры в офисах и школах с зарплатами, которые помогали им быть более независимыми. [77] С их стремлением к свободе и независимости произошли изменения в моде. [78] Одним из наиболее драматичных послевоенных изменений в моде стал женский силуэт; длина платья изменилась с пола на щиколотку и колено, став более смелой и соблазнительной. Новый дресс-код подчеркивал молодость: корсеты остались позади, а одежда стала свободнее, с более естественными линиями. Фигура «песочные часы» больше не была популярной, и более стройный, мальчишеский тип телосложения считался привлекательным. Флэпперы были известны этим, а также своим приподнятым настроением, флиртом и безрассудством, когда дело касалось поиска веселья и острых ощущений. [79]

Коко Шанель была одной из самых загадочных фигур моды 1920-х годов. Она была признана за ее авангардный дизайн; ее одежда представляла собой смесь ношения, удобства и элегантности. Она была той, кто ввел в моду другую эстетику, особенно другое чувство женственности, и основывала свой дизайн на новой этике; она создавала одежду для активной женщины, которая могла чувствовать себя непринужденно в своем платье. [80] Основной целью Шанель было расширение свободы. Она была пионером в ношении женщинами брюк и маленького черного платья , которые были признаками более независимого образа жизни.

Большинство британских историков описывают 1920-е годы как эпоху домашнего хозяйства для женщин с небольшим феминистским прогрессом, за исключением полного избирательного права, которое пришло в 1928 году. [81] Напротив, утверждает Элисон Лайт , литературные источники показывают, что многие британские женщины наслаждались:

... бодрое чувство волнения и освобождения, которое оживляет так много более широких культурных мероприятий, которыми различные группы женщин наслаждались в этот период. Какие новые виды социальных и личных возможностей, например, предлагались меняющимися культурами спорта и развлечений ... новыми моделями домашней жизни ... новыми формами бытовых приборов, новым отношением к домашнему хозяйству? [82]

С принятием 19-й поправки в 1920 году, которая дала женщинам право голоса , американские феминистки добились политического равенства, которого они ждали. Между «новыми» женщинами 1920-х годов и предыдущим поколением начал формироваться разрыв поколений. До принятия 19-й поправки феминистки обычно считали, что женщины не могут успешно заниматься и карьерой, и семьей, полагая, что одно по своей сути будет подавлять развитие другого. Этот менталитет начал меняться в 1920-х годах, поскольку все больше женщин стали желать не только успешной собственной карьеры, но и семьи. [83] «Новая» женщина меньше инвестировала в социальную службу, чем прогрессивные поколения, и, соответствуя потребительскому духу эпохи, она стремилась конкурировать и находить личное удовлетворение. [84] Высшее образование быстро расширялось для женщин. Линда Эйзенманн утверждает: «Новые возможности для женщин в колледжах кардинально изменили представление о женственности, бросив вызов викторианскому убеждению, что социальные роли мужчин и женщин коренятся в биологии». [85]

Рекламные агентства эксплуатировали новый статус женщин, например, публикуя рекламу автомобилей в женских журналах, в то время, когда подавляющее большинство покупателей и водителей были мужчинами. Новая реклама продвигала новые свободы для обеспеченных женщин, а также указывала на внешние границы новых свобод. Автомобили были больше, чем просто практическими устройствами. Они также были весьма заметными символами богатства, мобильности и современности. Реклама, писала Эйнав Рабинович-Фокс, «предлагала женщинам визуальный словарь, чтобы представить их новые социальные и политические роли как граждан и играть активную роль в формировании их идентичности как современных женщин». [86]

Значительные изменения в жизни работающих женщин произошли в 1920-х годах. Первая мировая война временно позволила женщинам войти в такие отрасли, как химическая, автомобильная и сталелитейная промышленность, которые когда-то считались неподходящей работой для женщин. [87] Чернокожие женщины, которые исторически были отстранены от работы на фабриках, начали находить место в промышленности во время Первой мировой войны, соглашаясь на более низкую заработную плату и заменяя потерянный труд иммигрантов и на тяжелую работу. Однако, как и у других женщин во время Первой мировой войны, их успех был лишь временным; большинство чернокожих женщин также были вытеснены с работы на фабриках после войны. В 1920 году 75% чернокожих женщин-рабочих состояли из сельскохозяйственных рабочих, домашней прислуги и работниц прачечных. [88]

Законодательство, принятое в начале 20-го века, установило минимальную заработную плату и заставило многие фабрики сократить свои рабочие дни. Это сместило фокус в 1920-х годах на производительность труда для удовлетворения спроса. Фабрики поощряли рабочих производить быстрее и эффективнее с помощью ускорений и бонусных систем, увеличивая давление на фабричных рабочих. Несмотря на нагрузку на женщин на фабриках, бурно развивающаяся экономика 1920-х годов означала больше возможностей даже для низших классов. Многим молодым девушкам из рабочего класса не нужно было помогать содержать свои семьи, как это было у предыдущих поколений, и их часто поощряли искать работу или получать профессиональную подготовку, что приводило к социальной мобильности. [89]

Достижение избирательного права привело к тому, что феминистки переориентировали свои усилия на другие цели. Такие группы, как Национальная женская партия, продолжили политическую борьбу, предложив Поправку о равных правах в 1923 году и работая над отменой законов, которые использовали пол для дискриминации женщин, [90] но многие женщины переключили свое внимание с политики на то, чтобы бросить вызов традиционным определениям женственности.

Молодые женщины, особенно, начали заявлять о своих правах на собственные тела и принимать участие в сексуальном освобождении своего поколения. Многие из идей, которые подпитывали это изменение в сексуальной мысли, уже витали в интеллектуальных кругах Нью-Йорка до Первой мировой войны, в трудах Зигмунда Фрейда , Хэвлока Эллиса и Эллен Кей . Там мыслители утверждали, что секс не только является центральным в человеческом опыте, но и что женщины являются сексуальными существами с человеческими импульсами и желаниями, и сдерживание этих импульсов было саморазрушительным. К 1920-м годам эти идеи проникли в мейнстрим. [91]

In the 1920s, the co-ed emerged, as women began attending large state colleges and universities. Women entered into the mainstream middle class experience but took on a gendered role within society. Women typically took classes such as home economics, "Husband and Wife", "Motherhood" and "The Family as an Economic Unit". In an increasingly conservative postwar era, a young woman commonly would attend college with the intention of finding a suitable husband. Fueled by ideas of sexual liberation, dating underwent major changes on college campuses. With the advent of the automobile, courtship occurred in a much more private setting. "Petting", sexual relations without intercourse, became the social norm for a portion of college students.[92]

Despite women's increased knowledge of pleasure and sex, the decade of unfettered capitalism that was the 1920s gave birth to the "feminine mystique". With this formulation, all women wanted to marry, all good women stayed at home with their children, cooking and cleaning, and the best women did the aforementioned and in addition, exercised their purchasing power freely and as frequently as possible to better their families and their homes.[93]

The Allied victory in World War I seems to mark the triumph of liberalism, not just in the Allied countries themselves, but also in Germany and in the new states of Eastern Europe, as well as Japan. Authoritarian militarism as typified by Germany had been defeated and discredited. Historian Martin Blinkhorn argues that the liberal themes were ascendant in terms of "cultural pluralism, religious and ethnic toleration, national self-determination, free-market economics, representative and responsible government, free trade, unionism, and the peaceful settlement of international disputes through a new body, the League of Nations".[94] However, as early as 1917, the emerging liberal order was being challenged by the new communist movement taking inspiration from the Russian Revolution. Communist revolts were beaten back everywhere else, but they did succeed in Russia.[95]

Homosexuality became much more visible and somewhat more acceptable. London, New York, Paris, Rome,[96] and Berlin were important centers of the new ethic.[97] Historian Jason Crouthamel argues that in Germany, the First World War promoted homosexual emancipation because it provided an ideal of comradeship which redefined homosexuality and masculinity. The many gay rights groups in Weimar Germany favored a militarised rhetoric with a vision of a spiritually and politically emancipated hypermasculine gay man who fought to legitimize "friendship" and secure civil rights.[98] Ramsey explores several variations. On the left, the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (Scientific-Humanitarian Committee; WhK) reasserted the traditional view that homosexuals were an effeminate "third sex" whose sexual ambiguity and nonconformity was biologically determined. The radical nationalist Gemeinschaft der Eigenen (Community of the Self-Owned) proudly proclaimed homosexuality as heir to the manly German and classical Greek traditions of homoerotic male bonding, which enhanced the arts and glorified relationships with young men. The politically centrist Bund für Menschenrecht (League for Human Rights) engaged in a struggle for human rights, advising gays to live in accordance with the mores of middle-class German respectability.[99]

Humor was used to assist in acceptability. One popular American song, "Masculine Women, Feminine Men",[100] was released in 1926 and recorded by numerous artists of the day; it included these lyrics:[101]

Masculine women, Feminine men

Which is the rooster, which is the hen?

It's hard to tell 'em apart today! And, say!

Sister is busy learning to shave,

Brother just loves his permanent wave,

It's hard to tell 'em apart today! Hey, hey!

Girls were girls and boys were boys when I was a tot,

Now we don't know who is who, or even what's what!

Knickers and trousers, baggy and wide,

Nobody knows who's walking inside,

Those masculine women and feminine men![102]

The relative liberalism of the decade is demonstrated by the fact that the actor William Haines, regularly named in newspapers and magazines as the No. 1 male box-office draw, openly lived in a gay relationship with his partner, Jimmie Shields. Other popular gay actors/actresses of the decade included Alla Nazimova and Ramón Novarro.[103] In 1927, Mae West wrote a play about homosexuality called The Drag,[104] and alluded to the work of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. It was a box-office success. West regarded talking about sex as a basic human rights issue, and was also an early advocate of gay rights.[105]

Profound hostility did not abate in more remote areas such as western Canada.[106] With the return of a conservative mood in the 1930s, the public grew intolerant of homosexuality, and gay actors were forced to choose between retiring or agreeing to hide their sexuality even in Hollywood.[107]

Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) played a major role in psychoanalysis, which impacted avant-garde thinking, especially in the humanities and artistic fields. Historian Roy Porter wrote:

Other influential proponents of psychoanalysis included Alfred Adler (1870–1937), Karen Horney (1885–1952), Carl Jung (1875–1961), Otto Rank (1884–1939), Helene Deutsch (1884–1982), and Freud's daughter Anna (1895–1982). Adler argued that a neurotic individual would overcompensate by manifesting aggression. Porter notes that Adler's views became part of "an American commitment to social stability based on individual adjustment and adaptation to healthy, social forms".[108]

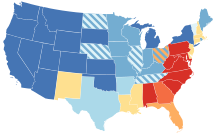

The United States became more anti-immigration in policy. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921, intended to be a temporary measure, set numerical limitations on immigration from countries outside the Western Hemisphere, capped at approximately 357,000 total annually. The Immigration Act of 1924 made permanent a more restrictive total cap of around 150,000 per annum, based on the National Origins Formula system of quotas limiting immigration to a fraction proportionate to an ethnic group's existing share of the United States population in 1920.[109][110] The goal was to freeze the pattern of European ethnic composition, and to exclude almost all Asians. Hispanics were not restricted.[111]

Australia, New Zealand, and Canada also sharply restricted or ended Asian immigration. In Canada, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 prevented almost all immigration from Asia. Other laws curbed immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe.[112][113][114][115]

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the progressive movement gradually caused local communities in many parts of Western Europe and North America to tighten restrictions of vice activities, particularly gambling, alcohol, and narcotics (though splinters of this same movement were also involved in racial segregation in the U.S.). This movement gained its strongest traction in the U.S. leading to the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the associated Volstead Act which made illegal the manufacture, import and sale of beer, wine and hard liquor (though drinking was technically not illegal). The laws were specifically promoted by evangelical Protestant churches and the Anti-Saloon League to reduce drunkenness, petty crime, domestic abuse, corrupt saloon-politics, and (in 1918), Germanic influences. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was an active supporter in rural areas, but cities generally left enforcement to a small number of federal officials. The various restrictions on alcohol and gambling were widely unpopular leading to rampant and flagrant violations of the law, and consequently to a rapid rise of organized crime around the nation (as typified by Chicago's Al Capone).[116] In Canada, prohibition ended much earlier than in the U.S., and barely took effect at all in the province of Quebec, which led to Montreal's becoming a tourist destination for legal alcohol consumption. The continuation of legal alcohol production in Canada soon led to a new industry in smuggling liquor into the U.S.[117]

Speakeasies were illegal bars selling beer and liquor after paying off local police and government officials. They became popular in major cities and helped fund large-scale gangsters operations such as those of Lucky Luciano, Al Capone, Meyer Lansky, Bugs Moran, Moe Dalitz, Joseph Ardizzone, and Sam Maceo. They operated with connections to organized crime and liquor smuggling. While the U.S. Federal Government agents raided such establishments and arrested many of the small figures and smugglers, they rarely managed to get the big bosses; the business of running speakeasies was so lucrative that such establishments continued to flourish throughout the nation. In major cities, speakeasies could often be elaborate, offering food, live bands, and floor shows. Many shows in cities such as New York, Paris, London, Berlin, and San Francisco featured female impersonators or drag performers in a wave of popularity known as the Pansy Craze.[118][119] Police were notoriously bribed by speakeasy operators to either leave them alone or at least give them advance notice of any planned raid.[120]

The Roaring Twenties was a period of literary creativity, and works of several notable authors appeared during the period. D. H. Lawrence's novel Lady Chatterley's Lover was a scandal at the time because of its explicit descriptions of sex. After an initially mixed response, T. S. Eliot's multi-part poem The Waste Land came to be regarded as a seminal Modernist work, and its experimentation with intertextuality would heavily influence the evolution of 20th Century poetry. Books that take the 1920s as their subject include:

The 1920s also saw the widespread popularity of the pulp magazine. Printed on cheap pulp paper, these magazines provided affordable entertainment to the masses and quickly became one of the most popular forms of media during the decade. Many prominent writers of the 20th century would get their start writing for pulps, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, Dashiell Hammett, and H. P. Lovecraft. Pulp fiction magazines would last in popularity until the 1950s.[121]

Charles Lindbergh gained sudden great international fame as the first pilot to fly solo and non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean, flying from Roosevelt Airfield (Nassau County, Long Island), New York to Paris on May 20–21, 1927. He had a single-engine airplane, the "Spirit of St. Louis", which had been designed by Donald A. Hall and custom built by Ryan Airlines of San Diego, California. His flight took 33.5 hours. The president of France bestowed on him the French Legion of Honor and, on his arrival back in the United States, a fleet of warships and aircraft escorted him to Washington, D.C., where President Calvin Coolidge awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross.

The Roaring Twenties was the breakout decade for sports across the modern world. Citizens from all parts of the country flocked to see the top athletes of the day compete in arenas and stadiums. Their exploits were loudly and highly praised in the new "gee whiz" style of sports journalism that was emerging; champions of this style of writing included the legendary writers Grantland Rice and Damon Runyon in American sports literature presented a new form of heroism departing from the traditional models of masculinity.[122]

High school and junior high school students were offered to play sports that they had not been able to play in the past. Several sports, such as golf, that had previously been unavailable to the middle-class finally became available.

In 1929, driver Henry Segrave reached a record land speed of 231.44 mph in his car, the Golden Arrow.[123]

Following the 1922 Latin American Games in Rio de Janeiro, IOC officials toured the region, helping countries establish national Olympic committees and prepare for future competition. In some countries, such as Brazil, sporting and political rivalries hindered progress as opposing factions battled for control of the international sport. The 1924 Olympic Games in Paris and the 1928 games in Amsterdam saw greatly increased participation from Latin American athletes.[124]

Sports journalism, modernity, and nationalism excited Egypt. Egyptians of all classes were captivated by news of the Egyptian national soccer team's performance in international competitions. Success or failure in the Olympics of 1924 and 1928 was more than a betting opportunity but became an index of Egyptian independence and a desire to be seen as modern by Europe. Egyptians also saw these competitions as a way to distinguish themselves from the traditionalism of the rest of Africa.[125]

The Greek government of Eleftherios Venizelos initiated a number of programs involving physical education in the public schools and raised the profile of sports competition. Other Balkan nations also became more involved in sports and participated in several precursors of the Balkan Games, competing sometimes with Western European teams. The Balkan Games, first held in Athens in 1929 as an experiment, proved a sporting and a diplomatic success. From the beginning, the games, held in Greece through 1933, sought to improve relations among Greece, Turkey, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Albania. As a political and diplomatic event, the games worked in conjunction with an annual Balkan Conference, which resolved issues between these often-feuding nations. The results were quite successful; officials from all countries routinely praised the games' athletes and organizers. During a period of persistent and systematic efforts to create rapprochement and unity in the region, this series of athletic meetings played a key role.[126]

The most popular American athlete of the 1920s was baseball player Babe Ruth. His characteristic home-run hitting heralded a new epoch in the history of the sport (the "live-ball era"), and his high style of living fascinated the nation and made him one of the highest-profile figures of the decade. Fans were enthralled in 1927 when Ruth hit 60 home runs, setting a new single-season home run record that was not broken until 1961. Together with another up-and-coming star named Lou Gehrig, Ruth laid the foundation of future New York Yankees dynasties.

A former bar room brawler named Jack Dempsey, also known as The Manassa Mauler, won the world heavyweight boxing title and became the most celebrated pugilist of his time. Enrique Chaffardet the Venezuelan Featherweight World Champion was the most sought-after boxer in 1920s Brooklyn, New York City. College football captivated fans, with notables such as Red Grange, running back of the University of Illinois, and Knute Rockne who coached Notre Dame's football program to great success on the field and nationwide notoriety. Grange also played a role in the development of professional football in the mid-1920s by signing on with the NFL's Chicago Bears. Bill Tilden thoroughly dominated his competition in tennis, cementing his reputation as one of the greatest tennis players of all time. Bobby Jones also popularized golf with his spectacular successes on the links. Ruth, Dempsey, Grange, Tilden, and Jones are collectively referred to as the "Big Five" sporting icons of the Roaring Twenties.

During the 19th century, vices such as gambling, alcohol, and narcotics had been popular throughout the United States in spite of not always being technically legal. Enforcement against these vices had always been spotty. Indeed, most major cities established red-light districts to regulate gambling and prostitution despite the fact that these vices were typically illegal. However, with the rise of the progressive movement in the early 20th century, laws gradually became tighter with most gambling, alcohol, and narcotics outlawed by the 1920s. Because of widespread public opposition to these prohibitions, especially alcohol, a great economic opportunity was created for criminal enterprises. Organized crime blossomed during this era, particularly the American Mafia.[127] After the 18th Amendment went into effect, bootlegging became widespread. So lucrative were these vices that some entire cities in the U.S. became illegal gaming centers with vice actually supported by the local governments. Notable examples include Miami, Florida, and Galveston, Texas. Many of these criminal enterprises would long outlast the Roaring Twenties and ultimately were instrumental in establishing Las Vegas as a gambling center.

Weimar culture was the flourishing of the arts and sciences in Germany during the Weimar Republic, from 1918 until Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1933.[128] 1920s Berlin was at the hectic center of the Weimar culture. Although not part of Germany, German-speaking Austria, and particularly Vienna, is often included as part of Weimar culture.[129] Bauhaus was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts. Its goal of unifying art, craft, and technology became influential worldwide, especially in architecture.[130]

Germany, and Berlin in particular, was fertile ground for intellectuals, artists, and innovators from many fields. The social environment was chaotic, and politics were passionate. German university faculties became universally open to Jewish scholars in 1918. Leading Jewish intellectuals on university faculties included physicist Albert Einstein; sociologists Karl Mannheim, Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse; philosophers Ernst Cassirer and Edmund Husserl; sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld; political theorists Arthur Rosenberg and Gustav Meyer; and many others. Nine German citizens were awarded Nobel Prizes during the Weimar Republic, five of whom were Jewish scientists, including two in medicine.[131]

Sport took on a new importance as the human body became a focus that pointed away from the heated rhetoric of standard politics. The new emphasis reflected the search for freedom by young Germans alienated from rationalized work routines.[132]

The 1920s saw dramatic innovations in American political campaign techniques, based especially on new advertising methods that had worked so well selling war bonds during World War I. Governor James M. Cox of Ohio, the Democratic Party candidate, made a whirlwind campaign that took him to rallies, train station speeches, and formal addresses, reaching audiences totaling perhaps 2,000,000 people. It resembled the William Jennings Bryan campaign of 1896. By contrast, the Republican Party candidate Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio relied upon a "front porch campaign". It brought 600,000 voters to Marion, Ohio, where Harding spoke from his home. Republican campaign manager Will Hays spent some $8,100,000; nearly four times the money Cox's campaign spent. Hays used national advertising in a major way (with advice from adman Albert Lasker). The theme was Harding's own slogan "America First". Thus the Republican advertisement in Collier's Magazine for October 30, 1920, demanded, "Let's be done with wiggle and wobble." The image presented in the ads was nationalistic, using catchphrases like "absolute control of the United States by the United States," "Independence means independence, now as in 1776," "This country will remain American. Its next President will remain in our own country," and "We decided long ago that we objected to a foreign government of our people."[133]

1920 was the first presidential campaign to be heavily covered by the press and to receive widespread newsreel coverage, and it was also the first modern campaign to use the power of Hollywood and Broadway stars who traveled to Marion for photo opportunities with Harding and his wife. Al Jolson, Lillian Russell, Douglas Fairbanks, and Mary Pickford, were among the celebrities to make the pilgrimage. Business icons Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Harvey Firestone also lent their cachet to the Front Porch Campaign.[134] On election night, November 2, 1920, commercial radio broadcast coverage of election returns for the first time. Announcers at KDKA-AM in Pittsburgh, PA read telegraph ticker results over the air as they came in. This single station could be heard over most of the Eastern United States by the small percentage of the population that had radio receivers.

Calvin Coolidge was inaugurated as president after the sudden death of President Warren G. Harding in 1923; he was re-elected in 1924 in a landslide against a divided opposition. Coolidge made use of the new medium of radio and made radio history several times while president: his inauguration was the first presidential inauguration broadcast on radio; on February 12, 1924, he became the first American president to deliver a political speech on radio. Herbert Hoover was elected president in 1928.

Unions grew very rapidly during the war but after a series of failed major strikes in steel, meatpacking and other industries, a long decade of decline weakened most unions and membership fell even as employment grew rapidly. Radical unionism virtually collapsed, in large part because of Federal repression during World War I by means of the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918.

The 1920s marked a period of sharp decline for the labor movement. Union membership and activities fell sharply in the face of economic prosperity, a lack of leadership within the movement, and anti-union sentiments from both employers and the government. The unions were much less able to organize strikes. In 1919, more than 4,000,000 workers (or 21% of the labor force) participated in about 3,600 strikes. In contrast, 1929 witnessed about 289,000 workers (or 1.2% of the workforce) stage only 900 strikes. Unemployment rarely dipped below 5% in the 1920s and few workers faced real wage losses.[135]

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. The politics of the 1920s was unfriendly toward the labor unions and liberal crusaders against business and so many, if not all, historians who emphasize those themes write off the decade. Urban cosmopolitan scholars recoiled at the moralism of prohibition and the intolerance of the nativists of the KKK and denounced the era. Historian Richard Hofstadter, for example, wrote in 1955 that prohibition "was a pseudo-reform, a pinched, parochial substitute for reform" that "was carried about America by the rural-evangelical virus."[136] However, as Arthur S. Link emphasized, the progressives did not simply roll over and play dead.[137] Link's argument for continuity through the 1920s stimulated a historiography that found Progressivism to be a potent force. Palmer, pointing to people like George Norris, wrote, "It is worth noting that progressivism, whilst temporarily losing the political initiative, remained popular in many western states and made its presence felt in Washington during both the Harding and Coolidge presidencies."[138] Gerster and Cords argued, "Since progressivism was a 'spirit' or an 'enthusiasm' rather than an easily definable force with common goals, it seems more accurate to argue that it produced a climate for reform which lasted well into the 1920s, if not beyond."[139]

Even the Klan has been seen in a new light as numerous social historians reported that Klansmen were "ordinary white Protestants" primarily interested in purification of the system, which had long been a core progressive goal.[140] In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan experienced a resurgence, spread all over the country, and found a significant popularity that has lingered to this day in the Midwest. It was claimed at the height of the second incarnation of the KKK, its membership exceeded 4 million people nationwide. The Klan did not shy away from using burning crosses and other intimidation tools to strike fear into their opponents, who included not just blacks but also Catholics, Jews, and anyone else who was not a white Protestant.[141] Massacres of black people were common in the 1920s. Tulsa, 1921: On May 31, 1921, a White mob descended on "Black Wall Street", a prosperous Black neighborhood in Tulsa. Over the next two days, they murdered more than 300 people, burned down 40 city blocks and left 10,000 Black residents homeless.[142]

What historians have identified as "business progressivism," with its emphasis on efficiency and typified by Henry Ford and Herbert Hoover[143] reached an apogee in the 1920s. Reynold M. Wik, for example, argues that Ford's "views on technology and the mechanization of rural America were generally enlightened, progressive, and often far ahead of his times."[144]

Tindall stresses the continuing importance of the progressive movement in the South in the 1920s involving increased democracy, efficient government, corporate regulation, social justice, and governmental public service.[145][146] William Link finds political progressivism dominant in most of the South in the 1920s.[147] Likewise, it was influential in Midwest.[148] In Birmingham, Alabama, the Klan violently repressed mixed-race unions but joined with white Protestant workers in a political movement that enacted reforms beneficial to the white working class. But Klan attention to working-class interests was circumstantial and rigidly restricted by race, religion, and ethnicity.[149]

Historians of women and of youth emphasize the strength of the progressive impulse in the 1920s.[150] Women consolidated their gains after the success of the suffrage movement, and moved into causes such as world peace,[151] good government, maternal care (the Sheppard–Towner Act of 1921),[152] and local support for education and public health.[153] The work was not nearly as dramatic as the suffrage crusade, but women voted[154] and operated quietly and effectively. Paul Fass, speaking of youth, wrote "Progressivism as an angle of vision, as an optimistic approach to social problems, was very much alive."[155] The international influences which had sparked a great many reform ideas likewise continued into the 1920s, as American ideas of modernity began to influence Europe.[156]

There is general agreement that the Progressive Era was over by 1932, especially since a majority of the remaining progressives opposed the New Deal.[157]

Canadian politics were dominated federally by the Liberal Party of Canada under William Lyon Mackenzie King. The federal government spent most of the decade disengaged from the economy and focused on paying off the large debts amassed during the war and during the era of railway over expansion. After the booming wheat economy of the early part of the century, the prairie provinces were troubled by low wheat prices. This played an important role in the development of Canada's first highly successful third political party, the Progressive Party of Canada that won the second most seats in the 1921 national election. As well with the creation of the Balfour Declaration of 1926, Canada achieved with other British former colonies autonomy, forming the British Commonwealth.

The Dow Jones Industrial Stock Index had continued its upward move for weeks, and coupled with heightened speculative activities, it gave an illusion that the bull market of 1928 to 1929 would last forever. On October 29, 1929, also known as Black Tuesday, stock prices on Wall Street collapsed. The events in the United States added to a worldwide depression, later called the Great Depression, that put millions of people out of work around the world throughout the 1930s.

The 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment, was proposed on February 20, 1933. The choice to legalize alcohol was left up to the states, and many states quickly took this opportunity to allow alcohol. Prohibition was officially ended with the ratification of the amendment on December 5, 1933.

The television show Boardwalk Empire is set chiefly in Atlantic City, New Jersey, during the Prohibition era of the 1920s.

The film The Great Gatsby is a 2013 historical romantic drama film based on the 1925 novel of the same name by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

For the 1987 album Bad, singer Michael Jackson's single "Smooth Criminal" featured an iconic video that took place during Prohibition in a speak-easy setting. This is also where his iconic anti-gravity lean was debuted.

For the classic album Rebel of the Underground released June 21, 2013, by recording artist Marcus Orelias, the album featured the song titled "Roaring 20s".

On September 2, 2013, musical duo Rizzle Kicks released their second album titled Roaring 20s under Universal Island.

On July 20, 2022, rap artist Flo Milli released her commercial debut album, You Still Here, Ho? which featured a bonus track called "Roaring 20s". The song was accompanied with a 1920s themed video.

Pray for the Wicked, the sixth studio album by American pop rock solo project Panic! at the Disco, released on June 22, 2018, features a song titled "Roaring 20s".

My Roaring 20s is the second studio album by American rock group Cheap Girls; it was released on October 9, 2009, and the title is a reference to the era.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)