Швейцария , официально Швейцарская Конфедерация , является страной, не имеющей выхода к морю, расположенной в западно-центральной Европе . [d] [13] Она граничит с Италией на юге, Францией на западе, Германией на севере и Австрией и Лихтенштейном на востоке. Швейцария географически разделена между Швейцарским плато , Альпами и Юрой ; Альпы занимают большую часть территории, в то время как большая часть населения страны в 9 миллионов человек сосредоточена на плато, где находятся ее крупнейшие города и экономические центры, включая Цюрих , Женеву и Базель . [14]

Швейцария берет свое начало от Старой Швейцарской Конфедерации , созданной в Позднем Средневековье после серии военных успехов против Австрии и Бургундии ; Федеральная хартия 1291 года считается основополагающим документом страны. Независимость Швейцарии от Священной Римской империи была официально признана в Вестфальском мире в 1648 году. Швейцария придерживается политики вооруженного нейтралитета с XVI века и не вела международных войн с 1815 года . Она вступила в Организацию Объединенных Наций только в 2002 году, но проводит активную внешнюю политику, которая включает частое участие в построении мира . [15]

Швейцария является родиной Красного Креста и местом расположения штаб-квартир или офисов большинства крупных международных организаций, включая ВТО , ВОЗ , МОТ , ФИФА , ВЭФ и ООН. Она является одним из основателей Европейской ассоциации свободной торговли (ЕАСТ), но не входит в Европейский союз (ЕС), Европейскую экономическую зону или еврозону ; однако она участвует в европейском едином рынке и Шенгенской зоне . Швейцария является федеративной республикой , состоящей из 26 кантонов , с федеральными органами власти, расположенными в Берне . [a] [2] [1]

Швейцария является одной из самых развитых стран мира с самым высоким номинальным богатством на душу населения [16] и восьмым по величине валовым внутренним продуктом (ВВП) на душу населения . [17] [18] Швейцария демонстрирует высокие результаты по нескольким международным показателям , включая экономическую конкурентоспособность и демократическое управление . Такие города, как Цюрих, Женева и Базель, занимают одни из самых высоких мест по качеству жизни, [19] [20] хотя и с одними из самых высоких расходов на жизнь . [21] Швейцария имеет международную репутацию благодаря своему устоявшемуся банковскому сектору, а также своему особому признанию за производство часов и шоколада.

В нем четыре основных языковых и культурных региона: немецкий, французский, итальянский и ретороманский . Хотя большинство швейцарцев говорят по-немецки, национальная идентичность довольно сплоченная, укорененная в общем историческом прошлом, общих ценностях, таких как федерализм и прямая демократия , [22] и альпийской символике. [23] [24] Швейцарская идентичность выходит за рамки языка, этнической принадлежности и религии, что приводит к тому, что Швейцарию называют Willensnation («нацией воли»), а не национальным государством . [25]

Английское название Switzerland является портманто от Switzer , устаревшего термина для швейцарца , который использовался в 16-19 веках, и land . [26] Английское прилагательное Swiss является заимствованием из французского Suisse , также используемого с 16 века. Название Switzer происходит от алеманнского Schwiizer , по происхождению житель Швица и связанной с ним территории , одного из кантонов Вальдштетте , которые сформировали ядро Старой Швейцарской Конфедерации . Швейцарцы начали принимать это название для себя после Швабской войны 1499 года, используя его наряду с термином для «конфедератов», Eidgenossen (дословно: товарищи по клятве ), используемым с 14 века.Код данных для Швейцарии , CH, происходит от латинского Confoederatio Helvetica ( Гельветическая Конфедерация ).

Топоним Швиц впервые упоминается в 972 году как древневерхненемецкое Suittes , возможно, связанное со словом swedan «жечь» (ср. древнескандинавское svíða «палить, жечь»), обозначая территорию леса, которая была сожжена и расчищена для строительства. [27] Название распространилось на территорию, находившуюся под властью кантона, и после Швабской войны 1499 года постепенно стало использоваться для всей Конфедерации. [28] [29] Швейцарско -немецкое название страны, Schwiiz , созвучно названию кантона и поселения, но отличается использованием определенного артикля ( d'Schwiiz для Конфедерации, [30] но просто Schwyz для кантона и города). [31] Долгое [iː] в швейцарском немецком языке исторически и до сих пор часто пишется как ⟨y⟩, а не ⟨ii⟩ , что сохраняет изначальную идентичность двух имен даже на письме.

Латинское название Confoederatio Helvetica было неологизировано и постепенно вводилось после образования федерального государства в 1848 году, возвращая нас к наполеоновской Гельветической республике . Оно появилось на монетах с 1879 года, было выгравировано на Федеральном дворце в 1902 году и после 1948 года использовалось в официальной печати [32] (например, банковский код ISO «CHF» для швейцарского франка , швейцарские почтовые марки («HELVETIA») и домен верхнего уровня страны «.ch» оба взяты из латинского названия государства). Helvetica происходит от Helvetii , галльского племени, жившего на Швейцарском плато до римской эпохи .

Гельвеция появилась как национальное олицетворение Швейцарской конфедерации в XVII веке в пьесе Иоганна Каспара Вейсенбаха 1672 года. [33]

Государство Швейцария обрело свою нынешнюю форму с принятием Швейцарской федеральной конституции в 1848 году. Предшественники Швейцарии создали оборонительный союз в 1291 году, образовав свободную конфедерацию , которая просуществовала на протяжении столетий.

Древнейшие следы существования гоминидов в Швейцарии датируются примерно 150 000 лет назад. [34] Древнейшие известные сельскохозяйственные поселения в Швейцарии, которые были найдены в Гэхлингене , датируются примерно 5300 годом до нашей эры. [34]

Самые ранние известные племена сформировали культуры Гальштата и Ла-Тена , названные в честь археологического памятника Ла-Тена на северной стороне озера Невшатель . Культура Ла-Тена развивалась и процветала в конце железного века примерно с 450 г. до н. э., [34] возможно, под влиянием греческой и этрусской цивилизаций. Одним из самых выдающихся племен Ла-Тена были гельветы , которые в основном занимали Швейцарское плато , наряду с ретийцами в восточных регионах. Столкнувшись с давлением германских племен, в 58 г. до н. э. гельветы под влиянием Оргеторикса , богатого аристократа, решили покинуть Швейцарское плато в поисках лучших возможностей в западной Галлии. Однако после загадочной смерти Оргеторикса племя продолжило миграцию, но было решительно разбито армиями Юлия Цезаря в битве при Бибракте , на территории современной восточной Франции. После поражения Цезарь заставил гельветов вернуться на свои исконные земли, где они подверглись строгим ограничениям на свою автономию и передвижения. [34] В 15 г. до н. э. Тиберий (впоследствии второй римский император) и его брат Друз завоевали Альпы, включив их в Римскую империю . Территория, занятая гельветами, сначала стала частью римской провинции Галлия Бельгика , а затем ее провинции Германия Верхняя . Восточная часть современной Швейцарии была включена в римскую провинцию Реция . Где-то в начале нашей эры римляне содержали большой лагерь под названием Виндонисса , ныне руины у слияния рек Ааре и Ройсс , недалеко от города Виндиш . [36]

Первый и второй век нашей эры был эпохой процветания на Швейцарском плато. Такие города, как Авентикум , Юлия Эквестрис и Аугуста Раурика , достигли значительных размеров, в то время как сотни сельскохозяйственных поместий ( Villae rusticae ) были основаны в сельской местности. [37]

Около 260 г. н. э. падение территории Agri Decumates к северу от Рейна превратило сегодняшнюю Швейцарию в пограничную землю Империи. Повторные набеги племен алеманнов спровоцировали разрушение римских городов и экономики, заставив население укрываться около римских крепостей, таких как Castrum Rauracense около Augusta Raurica. Империя построила еще одну линию обороны на северной границе (так называемый Donau-Iller-Rhine-Limes). В конце четвертого века возросшее германское давление заставило римлян отказаться от линейной концепции обороны. Швейцарское плато наконец-то было открыто для германских племен . [ требуется цитата ]

В раннем Средневековье , с конца четвертого века, западная часть современной Швейцарии была частью территории королей бургундов , которые ввели в этот регион французский язык. Алеманны заселили Швейцарское плато в пятом веке и долины Альп в восьмом веке, образовав Алеманию . Современная Швейцария была затем разделена между королевствами Алемания и Бургундия . [34] Весь регион стал частью расширяющейся Франкской империи в шестом веке после победы Хлодвига I над алеманнами при Толбиаке в 504 году нашей эры, а затем франкского господства над бургундами. [38] [39]

На протяжении оставшейся части шестого, седьмого и восьмого веков швейцарские регионы продолжали находиться под франкской гегемонией ( династии Меровингов и Каролингов ), но после ее расширения при Карле Великом Франкская империя была разделена Верденским договором в 843 году. [34] Территории современной Швейцарии были разделены на Среднюю Франкию и Восточную Франкию , пока они не были вновь объединены под властью Священной Римской империи около 1000 года нашей эры. [34]

В X веке, когда власть Каролингов ослабла, мадьяры разрушили Базель в 917 году и Санкт-Галлен в 926 году. В ответ Генрих Птицелов , тогдашний правитель Восточной Франкии, издал указ об укреплении ключевых поселений для защиты от этих вторжений. Были укреплены крупные деревни и города, включая стратегические места, такие как Цюрих и Санкт-Галлен. Эта инициатива привела к развитию того, что по сути было ранними городскими крепостями и городскими органами власти в Восточной Швейцарии. [37]

К 1200 году Швейцарское плато включало владения домов Савойи , Церингера , Габсбурга и Кибурга . [34] Некоторые регионы ( Ури , Швиц , Унтервальден , позже известные как Вальдштеттен ) получили имперское непосредственное право на прямой контроль над горными перевалами. С исчезновением мужской линии в 1263 году династия Кибургов пала в 1264 году нашей эры. Габсбурги под предводительством короля Рудольфа I (императора Священной Римской империи в 1273 году) предъявили права на земли Кибурга и присоединили их, расширив свою территорию до восточного Швейцарского плато. [38]

Старая швейцарская конфедерация была союзом общин долин центральных Альп. Конфедерацией управляли дворяне и патриции разных кантонов, которые содействовали управлению общими интересами и обеспечивали мир на горных торговых путях. Федеральная хартия 1291 года считается основополагающим документом конфедерации, хотя подобные союзы, вероятно, существовали десятилетиями ранее. Документ был согласован между сельскими общинами Ури , Швица и Унтервальдена . [40] [ нужна страница ] [41]

К 1353 году три первоначальных кантона объединились с кантонами Гларус и Цуг и городами-государствами Люцерн , Цюрих и Берн, чтобы сформировать «Старую конфедерацию» из восьми государств, которая существовала до конца XV века. [41] Расширение привело к увеличению власти и богатства конфедерации. К 1460 году конфедераты контролировали большую часть территории к югу и западу от Рейна до Альп и гор Юра , и был основан Базельский университет (с медицинским факультетом), установивший традицию химических и медицинских исследований. Это усилилось после побед над Габсбургами ( битва при Земпахе , битва при Нефельсе ), над Карлом Смелым Бургундским в 1470-х годах и успехов швейцарских наемников . Победа Швейцарии в Швабской войне против Швабского союза императора Максимилиана I в 1499 году фактически означала независимость в составе Священной Римской империи . [41] В 1501 году Базель [42] и Шаффхаузен присоединились к Старой Швейцарской конфедерации. [43 ]

Конфедерация приобрела репутацию непобедимой во время этих ранних войн, но расширение конфедерации потерпело неудачу в 1515 году из-за поражения Швейцарии в битве при Мариньяно . Это положило конец так называемой «героической» эпохе швейцарской истории. [41] Успех Реформации Цвингли в некоторых кантонах привел к межкантональным религиозным конфликтам в 1529 и 1531 годах ( войны Каппеля ). Только спустя более ста лет после этих внутренних войн, в 1648 году, по Вестфальскому миру , европейские страны признали независимость Швейцарии от Священной Римской империи и ее нейтралитет . [38] [39]

В ранний современный период швейцарской истории растущий авторитаризм патрициатских семей [44] в сочетании с финансовым кризисом после Тридцатилетней войны привели к Швейцарской крестьянской войне 1653 года . На фоне этой борьбы сохранялся конфликт между католическими и протестантскими кантонами, вылившийся в дальнейшее насилие во время Первой войны при Вилльмергене в 1656 году и Тоггенбургской войны (или Второй войны при Вилльмергене) в 1712 году. [41]

В 1798 году революционное французское правительство вторглось в Швейцарию и навязало новую единую конституцию. [41] Это централизовало управление страной, фактически упразднив кантоны: более того, Мюльхаузен вышел из состава Швейцарии, а долина Вальтеллина стала частью Цизальпинской республики . Новый режим, известный как Гельветическая республика, был крайне непопулярен. Вторгшаяся иностранная армия навязала и разрушила многовековые традиции, сделав Швейцарию не более чем французским государством-сателлитом . Жестокое подавление французами восстания Нидвальдена в сентябре 1798 года было примером гнетущего присутствия французской армии и сопротивления местного населения оккупации. [ необходима цитата ]

Когда началась война между Францией и ее соперниками, русские и австрийские войска вторглись в Швейцарию. Швейцарцы отказались сражаться вместе с французами во имя Гельветической республики. В 1803 году Наполеон организовал встречу ведущих швейцарских политиков с обеих сторон в Париже. Результатом стал Акт о посредничестве , который в значительной степени восстановил швейцарскую автономию и ввел Конфедерацию из 19 кантонов. [41] С этого времени большая часть швейцарской политики будет касаться баланса между традицией самоуправления кантонов и потребностью в центральном правительстве. [45]

В 1815 году Венский конгресс полностью восстановил независимость Швейцарии, и европейские державы признали постоянный нейтралитет Швейцарии. [38] [39] [41] Швейцарские войска служили иностранным правительствам до 1860 года, когда они сражались при осаде Гаэты . Договор позволил Швейцарии увеличить свою территорию, приняв кантоны Вале , Невшатель и Женева . Границы Швейцарии после этого претерпели лишь незначительные изменения. [46]

Восстановление власти патрициата было лишь временным. После периода беспорядков с повторяющимися жестокими столкновениями, такими как Цюрихский путч 1839 года, в 1847 году разразилась гражданская война ( Зондербундскриг ), когда некоторые католические кантоны попытались создать отдельный альянс (Зондербунд ) . [41] Война длилась меньше месяца, в результате чего погибло менее 100 человек, большинство из которых были убиты в результате дружественного огня . Зондербундскриг оказал значительное влияние на психологию и общество Швейцарии. [ необходима цитата ] [ кто? ]

Война убедила большинство швейцарцев в необходимости единства и силы. Швейцарцы из всех слоев общества, будь то католики или протестанты, либералы или консерваторы, поняли, что кантоны выиграют больше от слияния своих экономических и религиозных интересов. [ необходима цитата ]

Таким образом, в то время как остальная Европа видела революционные восстания , швейцарцы разработали конституцию, которая предусматривала федеральную структуру , во многом вдохновленную американским примером . Эта конституция предоставляла центральную власть, оставляя кантонам право на самоуправление по местным вопросам. Отдавая должное тем, кто поддерживал власть кантонов (Sonderbund Kantone), национальное собрание было разделено на верхнюю палату ( Совет штатов , два представителя от кантона) и нижнюю палату ( Национальный совет , с представителями, избираемыми со всей страны). Референдумы стали обязательными для любых поправок. [39] Эта новая конституция положила конец законной власти дворянства в Швейцарии . [47]

Была введена единая система мер и весов, и в 1850 году швейцарский франк стал единой швейцарской валютой , дополненной франком WIR в 1934 году. [48] Статья 11 конституции запрещала отправлять войска на службу за границу, что ознаменовало конец иностранной службы. Это сопровождалось ожиданием службы Святейшему Престолу , и швейцарцы по-прежнему были обязаны служить Франциску II Обеих Сицилий , а швейцарские гвардейцы присутствовали при осаде Гаэты в 1860 году . [ требуется цитата ]

Важным положением конституции было то, что при необходимости ее можно было полностью переписать, что позволяло ей развиваться как единому целому, а не изменяться по одной поправке за раз. [49] [ нужна страница ]

Эта необходимость вскоре себя проявила, когда рост населения и последовавшая за ним промышленная революция привели к призывам соответствующим образом изменить конституцию. Население отклонило ранний проект в 1872 году, но изменения привели к его принятию в 1874 году . [41] Он ввел факультативный референдум по законам на федеральном уровне. Он также установил федеральную ответственность за оборону, торговлю и юридические вопросы.

В 1891 году конституция была пересмотрена с необычайно сильными элементами прямой демократии , которые остаются уникальными и по сей день. [41]

Швейцария не была захвачена ни в одной из мировых войн. Во время Первой мировой войны Швейцария была домом для революционера и основателя Советского Союза Владимира Ильича Ульянова ( Владимира Ленина ), который оставался там до 1917 года. [50] Швейцарский нейтралитет был серьезно поставлен под сомнение недолгим делом Гримма-Гофмана в 1917 году. В 1920 году Швейцария вступила в Лигу Наций , которая базировалась в Женеве , после того как она была освобождена от военных требований. [51]

Во время Второй мировой войны немцы разработали подробные планы вторжения , [52] но Швейцария так и не была атакована. [53] Швейцария смогла сохранить независимость благодаря сочетанию военного сдерживания, уступок Германии и удачи, поскольку вмешались более крупные события во время войны. [39] [54] Генерал Анри Гизан , назначенный главнокомандующим на время войны, приказал провести всеобщую мобилизацию вооруженных сил. Швейцарская военная стратегия изменилась со статичной обороны на границах на организованное долгосрочное истощение и отход на сильные, хорошо укомплектованные позиции высоко в Альпах, известные как Редюит . Швейцария была важной базой для шпионажа с обеих сторон и часто выступала посредником в общении между странами Оси и союзниками . [54]

Торговля Швейцарии была заблокирована как союзниками, так и странами Оси. Экономическое сотрудничество и предоставление кредитов нацистской Германии варьировались в зависимости от предполагаемой вероятности вторжения и наличия других торговых партнеров. Уступки достигли пика после того, как в 1942 году было разорвано важнейшее железнодорожное сообщение через вишистскую Францию , в результате чего Швейцария (вместе с Лихтенштейном ) оказалась полностью изолированной от остального мира территорией, контролируемой странами Оси. В ходе войны Швейцария интернировала более 300 000 беженцев [55] при поддержке Международного Красного Креста , базирующегося в Женеве. Строгая политика иммиграции и предоставления убежища , а также финансовые отношения с нацистской Германией вызвали споры только в конце 20-го века. [56] : 521

Во время войны швейцарские ВВС вступали в бой с самолетами обеих сторон, сбив 11 самолетов Люфтваффе в мае и июне 1940 года, а затем заставив сбить других нарушителей после изменения политики из-за угроз со стороны Германии. Более 100 бомбардировщиков союзников и их экипажи были интернированы. Между 1940 и 1945 годами Швейцария подвергалась бомбардировкам союзников , что привело к гибели людей и материальному ущербу. [54] Среди городов и поселков, подвергшихся бомбардировкам, были Базель , Брузио , Кьяссо , Корноль , Женева, Кобленц , Нидервенинген , Рафц , Рененс , Самедан , Шаффхаузен , Штайн-на-Рейне , Тегервилен , Тайнген , Вальс и Цюрих. Союзные войска утверждали, что бомбардировки, нарушавшие 96-ю статью Устава войны , были вызваны ошибками навигации, отказом оборудования, погодными условиями и ошибками пилотов. Швейцарцы выразили опасения и обеспокоенность тем, что бомбардировки были направлены на то, чтобы оказать давление на Швейцарию и прекратить экономическое сотрудничество и нейтралитет с нацистской Германией. [57] В Англии состоялся военный трибунал. США выплатили 62 млн швейцарских франков в качестве репараций. [ необходима цитата ]

Отношение Швейцарии к беженцам было сложным и противоречивым; в течение войны она приняла около 300 000 беженцев [55], отказавшись принять десятки тысяч других, [56] : 107 включая евреев, преследуемых нацистами. [56] : 114

После войны швейцарское правительство экспортировало кредиты через благотворительный фонд, известный как Schweizerspende , и жертвовало средства на План Маршалла , чтобы помочь восстановлению Европы, усилия, которые в конечном итоге принесли пользу швейцарской экономике . [56] : 521

Во время Холодной войны швейцарские власти рассматривали возможность создания швейцарской ядерной бомбы . [58] Ведущие физики-ядерщики из Федерального технологического института Цюриха, такие как Пауль Шеррер, сделали это реальной возможностью. [59] В 1988 году был основан Институт Пауля Шеррера его имени для изучения терапевтического использования технологий нейтронного рассеяния . [60] Финансовые проблемы с оборонным бюджетом и этические соображения не позволили выделить существенные средства, и Договор о нераспространении ядерного оружия 1968 года рассматривался как приемлемая альтернатива. Планы по созданию ядерного оружия были прекращены к 1988 году. [61] Швейцария присоединилась к Совету Европы в 1963 году. [39]

Швейцария была последней западной республикой ( Княжество Лихтенштейн последовало за ней в 1984 году), предоставившей женщинам право голоса . Некоторые швейцарские кантоны одобрили это в 1959 году, в то время как на федеральном уровне это было достигнуто в 1971 году [53] [62] [ неудачная проверка ] и, после сопротивления, в последнем кантоне Аппенцелль-Иннерроден (одном из двух оставшихся Ландсгемайнде , наряду с Гларусом ) в 1990 году. После получения избирательного права на федеральном уровне политическое значение женщин быстро возросло. Первой женщиной в составе семи членов Федерального совета была Элизабет Копп , которая работала с 1984 по 1989 год, [53] а первой женщиной-президентом стала Рут Дрейфус в 1999 году. [63]

В 1979 году районы кантона Берн обрели независимость от Берна, образовав новый кантон Юра . 18 апреля 1999 года швейцарское население и кантоны проголосовали за полностью пересмотренную федеральную конституцию . [53]

В 2002 году Швейцария стала полноправным членом Организации Объединенных Наций, оставив Ватикан последним широко признанным государством без полноправного членства в ООН. Швейцария является одним из основателей ЕАСТ , но не Европейской экономической зоны (ЕЭЗ). Заявка на членство в Европейском союзе была отправлена в мае 1992 года, но не продвинулась с тех пор, как отклонила ЕЭЗ в декабре 1992 года [53] , когда Швейцария провела референдум по ЕЭЗ. Последовало несколько референдумов по вопросу ЕС; из-за сопротивления граждан заявка на членство была отозвана. Тем не менее, швейцарское законодательство постепенно меняется, чтобы соответствовать законодательству ЕС, и правительство подписало двусторонние соглашения с Европейским союзом. Швейцария, вместе с Лихтенштейном, была окружена ЕС с момента вступления Австрии в 1995 году. 5 июня 2005 года швейцарские избиратели большинством в 55% согласились присоединиться к Шенгенскому соглашению , результат, который комментаторы ЕС расценили как знак поддержки. [39] В сентябре 2020 года Швейцарская народная партия (SVP) инициировала референдум, призывающий к голосованию за прекращение действия пакта, разрешающего свободное перемещение людей из Европейского союза . [64] Однако избиратели отвергли попытку вернуть контроль над иммиграцией, отклонив предложение с перевесом примерно 63% против 37%. [65]

9 февраля 2014 года 50,3% швейцарских избирателей одобрили инициативу голосования, выдвинутую Швейцарской народной партией (SVP/UDC) по ограничению иммиграции . Эту инициативу в основном поддержали сельские (одобрение 57,6%) и пригородные группы (одобрение 51,2%), а также изолированные города (одобрение 51,3%), а также сильное большинство (одобрение 69,2%) в Тичино, в то время как столичные центры (отклонение 58,5%) и франкоязычная часть (отклонение 58,5%) отклонили ее. [66] В декабре 2016 года был достигнут политический компромисс с ЕС, который отменил квоты для граждан ЕС, но по-прежнему допускал благоприятное отношение к соискателям на работу из Швейцарии. [67] 27 сентября 2020 года 62% швейцарских избирателей отклонили референдум против свободного движения, проведенный SVP. [68]

Располагаясь на северной и южной стороне Альп в западно - центральной Европе, Швейцария охватывает разнообразные ландшафты и климаты на своих 41 285 квадратных километрах (15 940 квадратных миль). [69]

Швейцария расположена между 45° и 48° северной широты и 5° и 11° восточной долготы . Она состоит из трех основных топографических областей: Швейцарские Альпы на юге, Швейцарское плато или Центральное плато и горы Юра на западе. Альпы представляют собой горную цепь, проходящую через центральную и южную часть страны, составляя около 60% площади страны. Большая часть населения проживает на Швейцарском плато. Швейцарские Альпы содержат множество ледников, покрывающих 1063 квадратных километра (410 квадратных миль). Из них берут начало несколько крупных рек, таких как Рейн , Инн , Тичино и Рона , которые текут в четырех основных направлениях, распространяясь по всей Европе. Гидрографическая сеть включает несколько крупнейших водоемов пресной воды в Центральной и Западной Европе, среди которых Женевское озеро (Lac Léman на французском языке), Боденское озеро (Bodensee на немецком языке) и озеро Маджоре . В Швейцарии более 1500 озер, и на ее долю приходится 6% запасов пресной воды Европы. Озера и ледники покрывают около 6% территории страны. Женевское озеро является крупнейшим озером и делится им с Францией. Рона является как основным истоком, так и стоком Женевского озера. Боденское озеро является вторым по величине и, как и Женевское озеро, промежуточным звеном у Рейна на границе с Австрией и Германией. В то время как Рона впадает в Средиземное море во французском регионе Камарг , а Рейн впадает в Северное море в Роттердаме , на расстоянии около 1000 километров (620 миль) друг от друга, оба источника находятся всего в 22 километрах (14 милях) друг от друга в Швейцарских Альпах. [69] [70] 90% из 65 000-километровой сети рек и ручьев Швейцарии были выпрямлены, перекрыты плотинами, канализированы или уложены под землей в целях предотвращения стихийных бедствий, таких как наводнения, оползни и лавины. [71] 80% всей питьевой воды Швейцарии поступает из подземных источников. [72]

Сорок восемь гор имеют высоту 4000 метров (13 000 футов) или выше. [69] Монте-Роза высотой 4634 м (15 203 фута) является самой высокой, хотя Маттерхорн (4478 м или 14 692 фута) является наиболее известным. Обе расположены в Пеннинских Альпах в кантоне Вале , на границе с Италией. Часть Бернских Альп над глубокой ледниковой долиной Лаутербруннен , содержащая 72 водопада, хорошо известна пиками Юнгфрау (4158 м или 13 642 фута) , Эйгер и Мёнх , а также ее многочисленными живописными долинами. На юго-востоке также хорошо известна длинная долина Энгадин , охватывающая Санкт-Мориц ; самая высокая вершина в соседних Бернинских Альпах - Пиц Бернина (4049 м или 13 284 фута). [69]

Швейцарское плато имеет более открытые и холмистые ландшафты, частично лесистые, частично открытые пастбища, обычно с пасущимися стадами или овощными и фруктовыми полями, но оно все еще холмистое. Большие озера и самые большие швейцарские города находятся там. [69]

Швейцария состоит из двух небольших анклавов : Бюзинген принадлежит Германии, а Кампионе-д'Италия принадлежит Италии. [73] В Швейцарии нет эксклавов.

Климат Швейцарии в целом умеренный , но может сильно различаться в зависимости от местности, [74] от ледниковых условий на вершинах гор до почти средиземноморского климата на южной оконечности Швейцарии. Некоторые долины в южной части Швейцарии предлагают морозостойкие пальмы. Лето, как правило, теплое и влажное время от времени с периодическими осадками, идеально подходит для пастбищ/выпаса скота. Менее влажные зимы в горах могут иметь недельные интервалы стабильных условий. В то же время, более низкие земли, как правило, страдают от инверсии в такие периоды, скрывая солнце. [ необходима цитата ]

Погодное явление, известное как фён (с идентичным эффектом ветра чинук ), может произойти в любое время и характеризуется неожиданно теплым ветром, приносящим воздух с низкой относительной влажностью на север Альп во время дождливых периодов на склонах, обращенных на юг. Это работает в обоих направлениях через Альпы, но более эффективно, если дует с юга из-за более крутого шага для встречного ветра. Долины, идущие с юга на север, вызывают наилучший эффект. Самые сухие условия сохраняются во всех внутренних альпийских долинах, которые получают меньше осадков, потому что прибывающие облака теряют большую часть своего содержания влаги, пересекая горы, прежде чем достичь этих областей. Большие альпийские районы, такие как Граубюнден, остаются более сухими, чем предальпийские районы, и, как и в главной долине Вале , там выращивают виноград. [75]

Самые влажные условия сохраняются в высоких Альпах и кантоне Тичино , где много солнца, но время от времени идут сильные дожди. [75] Осадки, как правило, распределяются умеренно в течение года, с пиком летом. Осень — самый сухой сезон, зимой осадков выпадает меньше, чем летом, однако погодные условия в Швейцарии не находятся в стабильной климатической системе. Они могут меняться из года в год без строгих и предсказуемых периодов. [ требуется цитата ]

В Швейцарии есть два наземных экорегиона: западноевропейские широколиственные леса и альпийские хвойные и смешанные леса . [76]

Многочисленные небольшие долины Швейцарии, разделенные высокими горами, часто являются местом обитания уникальной экологии. Сами горные регионы предлагают богатый спектр растений, не встречающихся на других высотах. Климатические, геологические и топографические условия альпийского региона создают хрупкую экосистему, которая особенно чувствительна к изменению климата . [74] [77] Согласно Индексу экологической эффективности 2014 года , Швейцария занимает первое место среди 132 стран по охране окружающей среды благодаря своим высоким показателям по экологическому здоровью населения, своей сильной зависимости от возобновляемых источников энергии ( гидроэнергетика и геотермальная энергия) и уровню выбросов парниковых газов . [78] В 2020 году она заняла третье место из 180 стран. [79] Страна обязалась сократить выбросы парниковых газов на 50% к 2030 году по сравнению с уровнем 1990 года и планирует достичь нулевых выбросов к 2050 году. [80]

Однако доступ к биоемкости в Швейцарии намного ниже, чем в среднем по миру. В 2016 году на территории Швейцарии было 1,0 гектара [81] биоемкости на человека, что на 40 процентов меньше, чем в среднем по миру 1,6. Напротив, в 2016 году швейцарское потребление требовало 4,6 гектара биоемкости — их экологический след , в 4,6 раза больше, чем может поддерживать швейцарская территория. Остальное поступает из других стран и общих ресурсов (таких как атмосфера, на которую влияют выбросы парниковых газов). [81] Швейцария имела средний балл Индекса целостности лесного ландшафта 2019 года 3,53/10, что ставит ее на 150-е место в мире из 172 стран. [82]

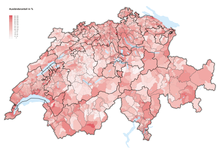

Около 85% населения проживает в городских районах. [83] [84] Швейцария превратилась из преимущественно сельской страны в городскую с 1930 по 2000 год. После 1935 года городское развитие захватило столько же швейцарского ландшафта, сколько и за предыдущие 2000 лет. Разрастание городов затрагивает плато, Юру и предгорья Альп, [85] вызывая обеспокоенность по поводу землепользования. [86] В 21 веке рост населения в городских районах выше, чем в сельской местности. [84]

Швейцария имеет густую сеть дополнительных крупных, средних и малых городов. [84] Плато густо заселено, около 400 человек на км 2 , и ландшафт демонстрирует непрерывные признаки человеческого присутствия. [87] Вес крупнейших мегаполисов — Цюриха , Женевы- Лозанны , Базеля и Берна — имеет тенденцию к увеличению. [84] [ необходимо разъяснение ] Важность этих городских территорий больше, чем предполагает их население. [84] Эти городские центры известны своим высоким качеством жизни. [88]

Средняя плотность населения в 2019 году составила 215,2 человек на квадратный километр (557 человек на квадратную милю). [89] : 79 В самом большом по площади кантоне Граубюнден , полностью расположенном в Альпах, плотность населения падает до 28,0 человек на квадратный километр (73 человека на квадратную милю). [89] : 30 В кантоне Цюрих с его крупной городской столицей плотность составляет 926,8 человек на квадратный километр (2400 человек на квадратную милю). [89] : 76

The Federal Constitution adopted in 1848 is the legal foundation of Switzerland's federal state.[90] A new Swiss Constitution was adopted in 1999 that did not introduce notable changes to the federal structure. It outlines rights of individuals and citizen participation in public affairs, divides the powers between the Confederation and the cantons and defines federal jurisdiction and authority. Three main bodies govern on the federal level:[91] the bicameral parliament (legislative), the Federal Council (executive) and the Federal Court (judicial).

The Swiss Parliament consists of two houses: the Council of States which has 46 representatives (two from each canton and one from each half-canton) who are elected under a system determined by each canton, and the National Council, which consists of 200 members who are elected under a system of proportional representation, reflecting each canton's population. Members serve part-time for four years (a Milizsystem or citizen legislature).[92] When both houses are in joint session, they are known collectively as the Federal Assembly. Through referendums, citizens may challenge any law passed by parliament and, through initiatives, introduce amendments to the federal constitution, thus making Switzerland a direct democracy.[90]

The Federal Council directs the federal government, the federal administration, and serves as a collective head of state. It is a collegial body of seven members, elected for a four-year term by the Federal Assembly, which also oversees the council. The President of the Confederation is elected by the Assembly from among the seven members, traditionally in rotation and for a one-year term; the President chairs the government and executes representative functions. The president is a primus inter pares with no additional powers and remains the head of a department within the administration.[90]

The government has been a coalition of the four major political parties since 1959, each party having a number of seats that roughly reflects its share of the electorate and representation in the federal parliament. The classic distribution of two CVP/PDC, two SPS/PSS, two FDP/PRD and one SVP/UDC as it stood from 1959 to 2003 was known as the "magic formula". Following the 2015 Federal Council elections, the seven seats in the Federal Council were distributed as follows:

The function of the Federal Supreme Court is to hear appeals against rulings of cantonal or federal courts. The judges are elected by the Federal Assembly for six-year terms.[93]

Direct democracy and federalism are hallmarks of the Swiss political system.[94] Swiss citizens are subject to three legal jurisdictions: the municipality, canton and federal levels. The 1848 and 1999 Swiss Constitutions define a system of direct democracy (sometimes called half-direct or representative direct democracy because it includes institutions of a representative democracy). The instruments of this system at the federal level, known as popular rights (‹See Tfd›German: Volksrechte, French: droits populaires, Italian: diritti popolari),[95] include the right to submit a federal initiative and a referendum, both of which may overturn parliamentary decisions.[90][96]

By calling a federal referendum, a group of citizens may challenge a law passed by parliament by gathering 50,000 signatures against the law within 100 days. If so, a national vote is scheduled where voters decide by a simple majority whether to accept or reject the law. Any eight cantons can also call a constitutional referendum on federal law.[90]

Similarly, the federal constitutional initiative allows citizens to put a constitutional amendment to a national vote, if 100,000 voters sign the proposed amendment within 18 months.[f] The Federal Council and the Federal Assembly can supplement the proposed amendment with a counterproposal. Then, voters must indicate a preference on the ballot if both proposals are accepted. Constitutional amendments, whether introduced by initiative or in parliament, must be accepted by a double majority of the national popular vote and the popular cantonal votes.[g][94]

The Swiss Confederation consists of 26 cantons:[90][97]

*These cantons are known as half-cantons.

The cantons are federated states. They have a permanent constitutional status and, in comparison with other countries, a high degree of independence. Under the Federal Constitution, all 26 cantons are equal in status, except that 6 (referred to often as the half-cantons) are represented by one councillor instead of two in the Council of States and have only half a cantonal vote with respect to the required cantonal majority in referendums on constitutional amendments. Each canton has its own constitution and its own parliament, government, police and courts.[97] However, considerable differences define the individual cantons, particularly in terms of population and geographical area. Their populations vary between 16,003 (Appenzell Innerrhoden) and 1,487,969 (Zurich), and their area between 37 km2 (14 sq mi) (Basel-Stadt) and 7,105 km2 (2,743 sq mi) (Grisons).

As of 2018 the cantons comprised 2,222 municipalities.

Until 1848, the loosely coupled Confederation did not have a central political organisation. Issues thought to affect the whole Confederation were the subject of periodic meetings in various locations.[98]

.jpg/440px-Bern_007_(35250800705).jpg)

In 1848, the federal constitution provided that details concerning federal institutions, such as their locations, should be addressed by the Federal Assembly (BV 1848 Art. 108). Thus on 28 November 1848, the Federal Assembly voted in the majority to locate the seat of government in Bern and, as a prototypical federal compromise, to assign other federal institutions, such as the Federal Polytechnical School (1854, the later ETH) to Zurich, and other institutions to Lucerne, such as the later SUVA (1912) and the Federal Insurance Court (1917).[1] Other federal institutions were subsequently attributed to Lausanne (Federal Supreme Court in 1872, and EPFL in 1969), Bellinzona (Federal Criminal Court, 2004), and St. Gallen (Federal Administrative Court and Federal Patent Court, 2012).

The 1999 Constitution does not mention a Federal City and the Federal Council has yet to address the matter.[99] Thus no city in Switzerland has the official status either of capital or of Federal City. Nevertheless, Bern is commonly referred to as "Federal City" (‹See Tfd›German: Bundesstadt, French: ville fédérale, Italian: città federale).

Traditionally, Switzerland avoids alliances that might entail military, political, or direct economic action and has been neutral since the end of its expansion in 1515. Its policy of neutrality was internationally recognised at the Congress of Vienna in 1815.[100][101] Swiss neutrality has been questioned at times.[102][103] In 2002 Switzerland became a full member of the United Nations.[100] It was the first state to join it by referendum. Switzerland maintains diplomatic relations with almost all countries and historically has served as an intermediary between other states.[100] Switzerland is not a member of the European Union; the Swiss people have consistently rejected membership since the early 1990s.[100] However, Switzerland does participate in the Schengen Area.[104]

Many international institutions have headquarters in Switzerland, in part because of its policy of neutrality. Geneva is the birthplace of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, the Geneva Conventions and, since 2006, hosts the United Nations Human Rights Council. Even though Switzerland is one of the most recent countries to join the United Nations, the Palace of Nations in Geneva is the second biggest centre for the United Nations after the headquarters in New York. Switzerland was a founding member and hosted the League of Nations.[51]

Apart from the United Nations headquarters, the Swiss Confederation is host to many UN agencies, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and about 200 other international organisations, including the World Trade Organization and the World Intellectual Property Organization.[100] The annual meetings of the World Economic Forum in Davos bring together business and political leaders from Switzerland and foreign countries to discuss important issues. The headquarters of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) moved to Basel in 1930.[citation needed]

Many sports federations and organisations are located in the country, including the International Handball Federation in Basel, the International Basketball Federation in Geneva, the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) in Nyon, the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) and the International Ice Hockey Federation both in Zurich, the International Cycling Union in Aigle, and the International Olympic Committee in Lausanne.[106]

Switzerland became a member of the United Nations Security Council for the 2023–2024 period.[107] According to the 2024 Global Peace Index, Switzerland is the 6th most peaceful country in the world.[108]

Although not a member, Switzerland maintains relationships with the EU and European countries through bilateral agreements. The Swiss have brought their economic practices largely into conformity with those of the EU, in an effort to compete internationally. EU membership faces considerable negative popular sentiment. It is opposed by the conservative SVP party, the largest party in the National Council, and not advocated by several other political parties. The membership application was formally withdrawn in 2016. The western French-speaking areas and the urban regions of the rest of the country tend to be more pro-EU, but do not form a significant share of the population.[109][110]

An Integration Office operates under the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Department of Economic Affairs. Seven bilateral agreements liberalised trade ties, taking effect in 2001. This first series of bilateral agreements included the free movement of persons. A second series of agreements covering nine areas was signed in 2004, including the Schengen Treaty and the Dublin Convention.[111]

In 2006, a referendum approved 1 billion francs of supportive investment in Southern and Central European countries in support of positive ties to the EU as a whole. A further referendum will be needed to approve 300 million francs to support Romania and Bulgaria and their recent admission.

The Swiss have faced EU and international pressure to reduce banking secrecy and raise tax rates to parity with the EU. Preparatory discussions involved four areas: the electricity market, participation in project Galileo, cooperating with the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and certificates of origin for food products.[112][needs update]

Switzerland is a member of the Schengen passport-free zone. Land border checkpoints apply on to goods movements, but not people.[113]

The Swiss Armed Forces, including the Land Forces and the Air Force, are composed mostly of conscripts, male citizens aged from 20 to 34 (in exceptional cases up to 50) years. Being a landlocked country, Switzerland has no navy; however, on lakes bordering neighbouring countries, armed boats patrol. Swiss citizens are prohibited from serving in foreign armies, except for the Swiss Guards of the Vatican, or if they are dual citizens of a foreign country and reside there.[citation needed]

The Swiss militia system stipulates that soldiers keep their army-issued equipment, including fully automatic personal weapons, at home.[114] Women can serve voluntarily. Men usually receive military conscription orders for training at the age of 18.[115] About two-thirds of young Swiss are found suitable for service; for the others, various forms of alternative service are available.[116] Annually, approximately 20,000 persons are trained in recruit centres for 18 to 21 weeks. The reform "Army XXI" was adopted by popular vote in 2003, replacing "Army 95", reducing the rolls from 400,000 to about 200,000. Of those, 120,000 are active in periodic Army training, and 80,000 are non-training reserves.[117]

The newest reform of the military, Weiterentwicklung der Armee (WEA; English: Further development of the Army), started in 2018 and was expected to reduce the number of army personnel to 100,000 by the end of 2022.[118][119]

Overall, three general mobilisations have been declared to ensure the integrity and neutrality of Switzerland. The first mobilisation was held in response to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71; while the second was in response to the First World War outbreak in August 1914; the third mobilisation took place in September 1939 in response to the German attack on Poland.[120]

Because of its neutrality policy, the Swiss army does not take part in armed conflicts in other countries but joins some peacekeeping missions. Since 2000 the armed force department has maintained the Onyx intelligence gathering system to monitor satellite communications.[121]

Gun politics in Switzerland are unique in Europe in that 2–3.5 million guns are in the hands of civilians, giving the nation an estimate of 28–41 guns per 100 people.[122] As per the Small Arms Survey, only 324,484 guns are owned by the military.[123] Only 143,372 are in the hands of soldiers.[124] However, ammunition is no longer issued.[125][126]

Switzerland has a stable, prosperous and high-tech economy. It is the world's wealthiest country per capita in multiple rankings. The country ranks as one of the least corrupt countries in the world,[128][129][130] while its banking sector is rated as "one of the most corrupt in the world".[131] It has the world's twentieth largest economy by nominal GDP and the thirty-eighth largest by purchasing power parity. As of 2021, it is the thirteenth largest exporter, and the fifth largest per capita. Zurich and Geneva are regarded as global cities, ranked as Alpha and Beta respectively. Basel is the capital of Switzerland's pharmaceutical industry, hosting Novartis, Roche, and many other players. It is one of the world's most important centres for the life sciences industry.[132]

Switzerland had the second-highest global rating in the Index of Economic Freedom 2023,[133] while also providing significant public services.[134] On a per capita basis, nominal GDP is higher than those of the larger Western and Central European economies and Japan,[135] while adjusted for purchasing power, Switzerland ranked 11th in 2017,[136] fifth in 2018[137] and ninth in 2020.[138]

Origin of the capital at the 30 biggest Swiss corporations, 2018:[139][h]

The 2016 World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report ranked Switzerland's economy as the world's most competitive;[140] as of 2019, it ranks fifth globally.[141] The European Union labeled it Europe's most innovative country and the most innovative country in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, as it had done in 2022, 2021, 2020 and 2019.[142][143][144][145] It ranked 20th of 189 countries in the Ease of Doing Business Index. Switzerland's slow growth in the 1990s and the early 2000s increased support for economic reforms and harmonisation with the European Union.[146][147] In 2020, IMD placed Switzerland first in attracting skilled workers.[148]

For much of the 20th century, Switzerland was the wealthiest country in Europe by a considerable margin (per capita GDP).[149] Switzerland has one of the world's largest account balances as a percentage of GDP.[150] In 2018, the canton of Basel-City had the highest GDP per capita, ahead of Zug and Geneva.[151] According to Credit Suisse, only about 37% of residents own their own homes, one of the lowest rates of home ownership in Europe. Housing and food price levels were 171% and 145% of the EU-25 index in 2007, compared to 113% and 104% in Germany.[152]

Switzerland is home to several large multinational corporations. The largest by revenue are Glencore, Gunvor, Nestlé, Mediterranean Shipping Company, Novartis, Hoffmann-La Roche, ABB, Mercuria Energy Group and Adecco.[153] Also, notable are UBS, Zurich Insurance, Richemont, Credit Suisse, Barry Callebaut, Swiss Re, Rolex, Tetra Pak, Swatch Group and Swiss International Air Lines.

Switzerland's most important economic sector is manufacturing. Manufactured products include specialty chemicals, health and pharmaceutical goods, scientific and precision measuring instruments and musical instruments. The largest exported goods are chemicals (34% of exported goods), machines/electronics (20.9%), and precision instruments/watches (16.9%).[152] The service sector – especially banking and insurance, commodities trading, tourism, and international organisations – is another important industry for Switzerland. Exported services amount to a third of exports.[152]

Agricultural protectionism—a rare exception to Switzerland's free trade policies—contributes to high food prices. Product market liberalisation is lagging behind many EU countries according to the OECD.[146] Apart from agriculture, economic and trade barriers between the European Union and Switzerland are minimal, and Switzerland has free trade agreements with many countries. Switzerland is a member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

Switzerland is considered as the "land of Cooperatives" with the ten largest cooperative companies accounting for more than 11% of GDP in 2018. They include Migros and Coop, the two largest retail companies in Switzerland.[154]

Switzerland is a tax haven.[155] The private sector economy dominates. It features low tax rates; tax revenue to GDP ratio is one of the smallest of developed countries. The Swiss Federal budget reached 62.8 billion Swiss francs in 2010, 11.35% of GDP; however, canton and municipality budgets are not counted as part of the federal budget. Total government spending is closer to 33.8% of GDP. The main sources of income for the federal government are the value-added tax (33% of tax revenue) and the direct federal tax (29%). The main areas of expenditure are in social welfare and finance/taxes. The expenditures of the Swiss Confederation have been growing from 7% of GDP in 1960 to 9.7% in 1990 and 10.7% in 2010. While the social welfare and finance sectors and tax grew from 35% in 1990 to 48.2% in 2010, a significant reduction of expenditures has been occurring in agriculture and national defence; from 26.5% to 12.4% (estimation for the year 2015).[156][157]

Slightly more than 5 million people work in Switzerland;[158] about 25% of employees belonged to a trade union in 2004.[159] Switzerland has a more flexible labor market than neighbouring countries and the unemployment rate is consistently low. The unemployment rate increased from 1.7% in June 2000 to 4.4% in December 2009.[160] It then decreased to 3.2% in 2014 and held steady for several years,[161] before further dropping to 2.5% in 2018 and 2.3% in 2019.[162] Population growth (from net immigration) reached 0.52% of population in 2004, increased in the following years before falling to 0.54% again in 2017.[152][163] The foreign citizen population was 28.9% in 2015, about the same as in Australia.[164]

In 2016, the median monthly gross income in Switzerland was 6,502 francs per month (equivalent to US$6,597 per month).[165] After rent, taxes and pension contributions, plus spending on goods and services, the average household has about 15% of its gross income left for savings. Though 61% of the population made less than the mean income, income inequality is relatively low with a Gini coefficient of 29.7, placing Switzerland among the top 20 countries. In 2015, the richest 1% owned 35% of the wealth.[166] Wealth inequality increased through 2019.[167]

About 8.2% of the population live below the national poverty line, defined in Switzerland as earning less than CHF3,990 per month for a household of two adults and two children, and a further 15% are at risk of poverty. Single-parent families, those with no post-compulsory education and those out of work are among the most likely to live below the poverty line. Although work is considered a way out of poverty, some 4.3% are considered working poor. One in ten jobs in Switzerland is considered low-paid; roughly 12% of Swiss workers hold such jobs, many of them women and foreigners.[165]

Education in Switzerland is diverse, because the constitution of Switzerland delegates the operation for the school system to the cantons.[168] Public and private schools are available, including many private international schools.

The minimum age for primary school is about six years, but most cantons provide a free "children's school" starting at age four or five.[168] Primary school continues until grade four, five or six, depending on the school. Traditionally, the first foreign language in school was one of the other Swiss languages, although in 2000, English was elevated in a few cantons.[168] At the end of primary school or at the beginning of secondary school, pupils are assigned according to their capacities into one of several sections (often three). The fastest learners are taught advanced classes to prepare for further studies and the matura,[168] while other students receive an education adapted to their needs.

Switzerland hosts 12 universities, ten of which are maintained at cantonal level and usually offer non-technical subjects. It ranked 87th on the 2019 Academic Ranking of World Universities.[169] The largest is the University of Zurich with nearly 25,000 students.[170] The Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ) and the University of Zurich are listed 20th and 54th respectively, on the 2015 Academic Ranking of World Universities.[171]

The federal government sponsors two institutes: the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ) in Zurich, founded in 1855 and the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Lausanne, founded in 1969, formerly associated with the University of Lausanne.[i][172][173]

Eight of the world's ten best hotel schools are located in Switzerland.[174] In addition, various universities of applied sciences are available. In business and management studies, the University of St. Gallen, (HSG) is ranked 329th in the world according to QS World University Rankings[175] and the International Institute for Management Development (IMD), was ranked first in open programmes worldwide.[176] Switzerland has the second highest rate (almost 18% in 2003) of foreign students in tertiary education, after Australia (slightly over 18%).[177][178]

The Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, located in Geneva, is continental Europe's oldest graduate school of international and development studies. It is widely held to be one of its most prestigious.[179][180]

Switzerland has birthed many Nobel Prize laureates. They include Albert Einstein,[181] who developed his special relativity in Bern. Later, Vladimir Prelog, Heinrich Rohrer, Richard Ernst, Edmond Fischer, Rolf Zinkernagel, Kurt Wüthrich and Jacques Dubochet received Nobel science prizes. In total, 114 laureates across all fields have a relationship to Switzerland.[182][j] The Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded nine times to organisations headquartered in Switzerland.[183]

Geneva and the nearby French department of Ain co-host the world's largest laboratory, CERN,[185] dedicated to particle physics research. Another important research centre is the Paul Scherrer Institute.

Notable inventions include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), diazepam (Valium), the scanning tunnelling microscope (Nobel prize) and Velcro. Some technologies enabled the exploration of new worlds such as the pressurised balloon of Auguste Piccard and the Bathyscaphe which permitted Jacques Piccard to reach the deepest point of the world's oceans.

The Swiss Space Office has been involved in various space technologies and programmes. It was one of the 10 founders of the European Space Agency in 1975 and is the seventh largest contributor to the ESA budget. In the private sector, several companies participate in the space industry, such as Oerlikon Space[186] or Maxon Motors.[187]

Electricity generated in Switzerland is 56% from hydroelectricity and 39% from nuclear power, producing negligible CO2. On 18 May 2003, two anti-nuclear referendums were defeated: Moratorium Plus, aimed at forbidding the building of new nuclear power plants (41.6% supported),[188] and Electricity Without Nuclear (33.7% supported) after a moratorium expired in 2000.[189] After the Fukushima nuclear disaster, in 2011 the government announced plans to end the use of nuclear energy in the following 20 to 30 years.[190] In November 2016, Swiss voters rejected a Green Party referendum to accelerate the phaseout of nuclear power (45.8% supported).[191] The Swiss Federal Office of Energy (SFOE) is responsible for energy supply and energy use within the Federal Department of Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications (DETEC). The agency supports the 2000-watt society initiative to cut the nation's energy use by more than half by 2050.[192]

The densest rail network in Europe[62][failed verification] spans 5,250 kilometres (3,260 mi) and carries over 596 million passengers annually as of 2015.[193] In 2015, each Swiss resident travelled on average 2,550 kilometres (1,580 mi) by rail, more than any other European country.[193] Virtually 100% of the network is electrified. 60% of the network is operated by the Swiss Federal Railways (SBB CFF FFS). Besides the second largest standard gauge railway company, BLS AG, two railways companies operate on narrow gauge networks: the Rhaetian Railway (RhB) in Graubünden, which includes some World Heritage lines,[194] and the Matterhorn Gotthard Bahn (MGB), which co-operates with RhB the Glacier Express between Zermatt and St. Moritz/Davos. Switzerland operates the world's longest and deepest railway tunnel and the first flat, low-level route through the Alps, the 57.1-kilometre-long (35.5 mi) Gotthard Base Tunnel, the largest part of the New Railway Link through the Alps (NRLA) project.

Switzerland has a publicly managed, toll-free road network financed by highway permits as well as vehicle and petrol taxes. The Swiss autobahn/autoroute system requires the annual purchase of a vignette (toll sticker)—for 40 Swiss francs—to use its roadways, including passenger cars and trucks. The Swiss autobahn/autoroute network stretches for 1,638 km (1,018 mi) and has one of the highest motorway densities in the world.[195]

Zurich Airport is Switzerland's largest international flight gateway; it handled 22.8 million passengers in 2012.[196] The other international airports are Geneva Airport (13.9 million passengers in 2012),[197] EuroAirport Basel Mulhouse Freiburg (located in France), Bern Airport, Lugano Airport, St. Gallen-Altenrhein Airport and Sion Airport. Swiss International Air Lines is the flag carrier. Its main hub is Zurich, but it is legally domiciled in Basel.

Switzerland has one of the best environmental records among developed nations.[198] It is a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol. With Mexico and South Korea, it forms the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG).[199]

The country is active in recycling and anti-littering programs and is one of the world's top recyclers, recovering 66% to 96% of recyclable materials, varying across the country.[200] The 2014 Global Green Economy Index placed Switzerland among the top 10 green economies.[201]

Switzerland has an economic system for garbage disposal, which is based mostly on recycling and energy-producing incinerators.[202] As in other European countries, the illegal disposal of garbage is heavily fined. In almost all Swiss municipalities, mandatory stickers or dedicated garbage bags allow the identification of disposable garbage.[203]

In common with other developed countries, the Swiss population increased rapidly during the industrial era, quadrupling between 1800 and 1990 and has continued to grow.

The population is about 9 million (2023 est.).[205] Population growth was projected into 2035, due mostly to immigration. Like most of Europe, Switzerland faces an ageing population, with a fertility rate close to replacement level.[206] Switzerland has one of the world's oldest populations, with an average age of 42.5 years.[207]

According to the World Factbook, ethnic groups in Switzerland are as follows: Swiss 69.2%, German 4.2%, Italian 3.2%, Portuguese 2.5%, French 2.1%, Kosovan 1.1%, Turkish 1%, other 16.7% (2020 est).[208] The Council of Europe figures suggest a population of around 30,000 Romani people in the country.[209]

As of 2023, resident foreigners made up 26.3% of Switzerland's population.[14] Most of these (83%) were from European countries. Italy provided the largest single group of foreigners, providing 14.7% of total foreign population, followed closely by Germany (14.0%), Portugal (11.7%), France (6.6%), Kosovo (5.1%), Spain (3.9%), Turkey (3.1%), North Macedonia (3.1%), Serbia (2.8%), Austria (2.0%), United Kingdom (1.9%), Bosnia and Herzegovina (1.3%) and Croatia (1.3%). Immigrants from Sri Lanka (1.3%), most of them former Tamil refugees, were the largest group of Asian origin (7.9%).[210]

2021 figures show that 39.5% (compared to 34.7% in 2012) of the permanent resident population aged 15 or over (around 2.89 million), had an immigrant background. 38% of the population with an immigrant background (1.1 million) held Swiss citizenship.[211][212]

In the 2000s, domestic and international institutions expressed concern about what was perceived as an increase in xenophobia. In reply to one critical report, the Federal Council noted that "racism unfortunately is present in Switzerland", but stated that the high proportion of foreign citizens in the country, as well as the generally successful integration of foreigners, underlined Switzerland's openness.[213] A follow-up study conducted in 2018 reported that 59% considered racism a serious problem in Switzerland.[214] The proportion of the population that claimed to have been targeted by racial discrimination increased from 10% in 2014 to almost 17% in 2018, according to the Federal Statistical Office.[215]

Switzerland has four national languages: mainly German (spoken natively by 62.8% of the population in 2016); French (22.9%) spoken natively in the west; and Italian (8.2%) spoken natively in the south.[218][217] The fourth national language, Romansh (0.5%), is a Romance language spoken locally in the southeastern trilingual canton of Grisons, and is designated by Article 4 of the Federal Constitution as a national language along with German, French, and Italian. In Article 70 it is mentioned as an official language if the authorities communicate with persons who speak Romansh. However, federal laws and other official acts do not need to be decreed in Romansh.

In 2016, the languages most spoken at home among permanent residents aged 15 and older were Swiss German (59.4%), French (23.5%), Standard German (10.6%), and Italian (8.5%). Other languages spoken at home included English (5.0%), Portuguese (3.8%), Albanian (3.0%), Spanish (2.6%) and Serbian and Croatian (2.5%). 6.9% reported speaking another language at home.[219] In 2014 almost two-thirds (64.4%) of the permanent resident population indicated speaking more than one language regularly.[220]

The federal government is obliged to communicate in the official languages, and in the federal parliament simultaneous translation is provided from and into German, French and Italian.[221]

Aside from the official forms of their respective languages, the four linguistic regions of Switzerland also have local dialectal forms. The role played by dialects in each linguistic region varies dramatically: in German-speaking regions, Swiss German dialects have become more prevalent since the second half of the 20th century, especially in the media, and are used as an everyday language for many, while the Swiss variety of Standard German is almost always used instead of dialect for written communication (c.f. diglossic usage of a language).[222] Conversely, in the French-speaking regions, local Franco-Provençal dialects have almost disappeared (only 6.3% of the population of Valais, 3.9% of Fribourg, and 3.1% of Jura still spoke dialects at the end of the 20th century), while in the Italian-speaking regions, the use of Lombard dialects is mostly limited to family settings and casual conversation.[222]

The principal official languages have terms not used outside of Switzerland, known as Helvetisms. German Helvetisms are, roughly speaking, a large group of words typical of Swiss Standard German that do not appear in Standard German, nor in other German dialects. These include terms from Switzerland's surrounding language cultures (German Billett[223] from French), from similar terms in another language (Italian azione used not only as act but also as discount from German Aktion).[224] Swiss French, while generally close to the French of France, also contains some Helvetisms. The most frequent characteristics of Helvetisms are in vocabulary, phrases, and pronunciation, although certain Helvetisms denote themselves as special in syntax and orthography. Duden, the comprehensive German dictionary, contains about 3000 Helvetisms.[224] Current French dictionaries, such as the Petit Larousse, include several hundred Helvetisms; notably, Swiss French uses different terms than that of France for the numbers 70 (septante) and 90 (nonante) and often 80 (huitante) as well.[225]

Learning one of the other national languages is compulsory for all Swiss pupils, hence many Swiss are supposed to be at least bilingual, especially those belonging to linguistic minority groups.[226] Because the largest part of Switzerland is German-speaking, many French, Italian, and Romansh speakers migrating to the rest of Switzerland and the children of those non-German-speaking Swiss born within the rest of Switzerland speak German. While learning one of the other national languages at school is important, most Swiss learn English to communicate with Swiss speakers of other languages, as it is perceived as a neutral means of communication. English often functions as the de facto lingua franca.[227]

Swiss residents are required to buy health insurance from private insurance companies, which in turn are required to accept every applicant. While the cost of the system is among the highest, its health outcomes compare well with other European countries; patients have been reported as in general, highly satisfied with it.[228][229][230] In 2012, life expectancy at birth was 80.4 years for men and 84.7 years for women[231] – the world's highest.[232][233] However, spending on health at 11.4% of GDP (2010) is on par with Germany and France (11.6%) and other European countries, but notably less than the US (17.6%).[234] From 1990, costs steadily increased.[235]

It is estimated that one out of six Swiss persons suffers from mental illness.[236]

According to a survey conducted by Addiction Switzerland, fourteen per cent of men and 6.5% of women between 20 and 24 reported consuming cannabis in the past 30 days in 2020, and 4 Swiss cities were listed among the top 10 European cities for cocaine use as measured in wastewater, down from 5 in 2018.[237][238]

Swiss culture is characterised by diversity, which is reflected in diverse traditional customs.[239] A region may be in some ways culturally connected to the neighbouring country that shares its language, all rooted in western European culture.[240] The linguistically isolated Romansh culture in Graubünden in eastern Switzerland constitutes an exception. It survives only in the upper valleys of the Rhine and the Inn and strives to maintain its rare linguistic tradition.

Switzerland is home to notable contributors to literature, art, architecture, music and sciences. In addition, the country attracted creatives during times of unrest or war.[241] Some 1000 museums are found in the country.[239]

Among the most important cultural performances held annually are the Paléo Festival, Lucerne Festival,[242] the Montreux Jazz Festival,[243] the Locarno International Film Festival and Art Basel.[244]

Alpine symbolism played an essential role in shaping Swiss history and the Swiss national identity.[23][245] Many alpine areas and ski resorts attract visitors for winter sports as well as hiking and mountain biking in summer. The quieter seasons are spring and autumn. A traditional pastoral culture predominates in many areas, and small farms are omnipresent in rural areas. Folk art is nurtured in organisations across the country. Switzerland most directly in appears in music, dance, poetry, wood carving, and embroidery. The alphorn, a trumpet-like musical instrument made of wood has joined yodeling and the accordion as epitomes of traditional Swiss music.[246][247]

Religion in Switzerland (age 15+, 2018–2020):[248][k]

Christianity is the predominant religion according to national surveys of Swiss Federal Statistical Office[k] (about 67% of resident population in 2016–2018[250] and 75% of Swiss citizens[251]), divided between the Catholic Church (35.8% of the population), the Swiss Reformed Church (23.8%), further Protestant churches (2.2%), Eastern Orthodoxy (2.5%), and other Christian denominations (2.2%).[250]

Switzerland has no official state religion, though most of the cantons (except Geneva and Neuchâtel) recognise official churches, either the Catholic Church or the Swiss Reformed Church. These churches, and in some cantons the Old Catholic Church and Jewish congregations, are financed by official taxation of members.[252] In 2020, the Roman Catholic Church had 3,048,475 registered and church tax paying members (corresponding to 35.2% of the total population), while the Swiss Reformed Church had 2,015,816 members (23.3% of the total population).[253][l]

26.3% of Swiss permanent residents are not affiliated with a religious community.[250]

As of 2020, according to a national survey conducted by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office,[k] Christian minority communities included Neo-Pietism (0.5%), Pentecostalism (0.4%, mostly incorporated in the Schweizer Pfingstmission), Apostolic communities (0.3%), other Protestant denominations (1.1%, including Methodism), the Old Catholic Church (0.1%), other Christian denominations (0.3%). Non-Christian religions are Islam (5.3%),[250] Hinduism (0.6%), Buddhism (0.5%), Judaism (0.25%) and others (0.4%).[248]

Historically, the country was about evenly balanced between Catholic and Protestant, in a complex patchwork. During the Reformation Switzerland became home to many reformers. Geneva converted to Protestantism in 1536, just before John Calvin arrived. In 1541, he founded the Republic of Geneva on his own ideals. It became known internationally as the Protestant Rome and housed such reformers as Theodore Beza, William Farel or Pierre Viret. Zurich became another reform stronghold around the same time, with Huldrych Zwingli and Heinrich Bullinger taking the lead. Anabaptists Felix Manz and Conrad Grebel also operated there. They were later joined by the fleeing Peter Martyr Vermigli and Hans Denck. Other centres included Basel (Andreas Karlstadt and Johannes Oecolampadius), Bern (Berchtold Haller and Niklaus Manuel), and St. Gallen (Joachim Vadian). One canton, Appenzell, was officially divided into Catholic and Protestant sections in 1597. The larger cities and their cantons (Bern, Geneva, Lausanne, Zurich and Basel) used to be predominantly Protestant. Central Switzerland, the Valais, the Ticino, Appenzell Innerrhodes, the Jura, and Fribourg are traditionally Catholic.

The Swiss Constitution of 1848, under the recent impression of the clashes of Catholic vs Protestant cantons that culminated in the Sonderbundskrieg, consciously defines a consociational state, allowing the peaceful co-existence of Catholics and Protestants.[citation needed] A 1980 initiative calling for the complete separation of church and state was rejected by 78.9% of the voters.[254] Some traditionally Protestant cantons and cities nowadays have a slight Catholic majority, because since about 1970 a steadily growing minority were not affiliated with any religious body (21.4% in Switzerland, 2012) especially in traditionally Protestant regions, such as Basel-City (42%), canton of Neuchâtel (38%), canton of Geneva (35%), canton of Vaud (26%), or Zurich city (city: >25%; canton: 23%).[255]

.jpg/440px-Jean-Jacques_Rousseau_(painted_portrait).jpg)

The earliest forms of literature were in German, reflecting the language's early predominance. In the 18th century, French became fashionable in Bern and elsewhere, while the influence of the French-speaking allies and subject lands increased.[256]

Among the classic authors of Swiss literature are Jeremias Gotthelf (1797–1854) and Gottfried Keller (1819–1890); later writers are Max Frisch (1911–1991) and Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921–1990), whose Das Versprechen (The Pledge) was released as a Hollywood film in 2001.[257]

Famous French-speaking writers were Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) and Germaine de Staël (1766–1817). More recent authors include Charles Ferdinand Ramuz (1878–1947), whose novels describe the lives of peasants and mountain dwellers, set in a harsh environment, and Blaise Cendrars (born Frédéric Sauser, 1887–1961).[257] Italian and Romansh-speaking authors also contributed to the Swiss literary landscape, generally in proportion to their number.

Probably the most famous Swiss literary creation, Heidi, the story of an orphan girl who lives with her grandfather in the Alps, is one of the most popular children's books and has come to be a symbol of Switzerland. Her creator, Johanna Spyri (1827–1901), wrote a number of books on similar themes.[257]

Freedom of the press and the right to free expression is guaranteed in the constitution.[258] The Swiss News Agency (SNA) broadcasts information in three of the four national languages—on politics, economics, society and culture. The SNA supplies almost all Swiss media and foreign media with its reporting.[258]

In Switzerland, the most influential newspapers include the German-language Tages-Anzeiger and Neue Zürcher Zeitung, as well as the French-language Le Temps. Additionally, almost every city has at least one local newspaper published in the predominant local language. [259][260]

The government exerts greater control over broadcast media than print media, especially due to financing and licensing.[citation needed] The Swiss Broadcasting Corporation, whose name was recently changed to SRG SSR, is charged with the production and distribution of radio and television content. SRG SSR studios are distributed across the various language regions. Radio content is produced in six central and four regional studios while video media are produced in Geneva, Zurich, Basel, and Lugano. An extensive cable network allows most Swiss to access content from neighbouring countries.[citation needed]

Skiing, snowboarding and mountaineering are among the most popular sports, reflecting the nature of the country[261] Winter sports are practised by natives and visitors. The bobsleigh was invented in St. Moritz.[262] The first world ski championships were held in Mürren (1931) and St. Moritz (1934). The latter town hosted the second Winter Olympic Games in 1928 and the fifth edition in 1948. Among its most successful skiers and world champions are Pirmin Zurbriggen and Didier Cuche.

The most prominently watched sports in Switzerland are football and ice hockey.[263]

The headquarters of the international football's and ice hockey's governing bodies, the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) and International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) are located in Zurich. Many other headquarters of international sports federations are located in Switzerland. For example, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), IOC's Olympic Museum and the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) are located in Lausanne.

Switzerland hosted the 1954 FIFA World Cup and was the joint host, with Austria, of the UEFA Euro 2008 tournament. The Swiss Super League is the nation's professional football club league. Europe's highest football pitch, at 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) above sea level, is located in Switzerland, the Ottmar Hitzfeld Stadium.[264]

Many Swiss follow ice hockey and support one of the 12 teams of the National League, which is the most attended league in Europe.[265] In 2009, Switzerland hosted the IIHF World Championship for the tenth time.[266] It also became World Vice-Champion in 2013 and 2018. Its numerous lakes make Switzerland an attractive sailing destination. The largest, Lake Geneva, is the home of the sailing team Alinghi which was the first European team to win the America's Cup in 2003 and which successfully defended the title in 2007.

_2_new.jpg/440px-Roger_Federer_(26_June_2009,_Wimbledon)_2_new.jpg)

Swiss tennis player Roger Federer is widely regarded as among the sport's greatest players. He won 20 Grand Slam tournaments overall including a record 8 Wimbledon titles. He won six ATP Finals.[268] He was ranked no. 1 in the ATP rankings for a record 237 consecutive weeks. He ended 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2009 ranked no. 1. Fellow Swiss players Martina Hingis and Stan Wawrinka also won multiple Grand Slam titles. Switzerland won the Davis Cup title in 2014.