Раннее христианство , иначе называемое Ранней Церковью или Палеохристианством , описывает историческую эпоху христианской религии вплоть до Первого Никейского собора в 325 году . Христианство распространилось из Леванта , по всей Римской империи и за ее пределы. Первоначально это развитие было тесно связано с уже существующими еврейскими центрами в Святой Земле и еврейской диаспорой по всему Восточному Средиземноморью . Первыми последователями христианства были евреи, которые обратились в веру, т. е. иудеохристиане , а также финикийцы , т. е. ливанские христиане . [1] Раннее христианство включает в себя Апостольский век и следует за ним, и в значительной степени пересекается с эрой Отцов Церкви .

Апостольские церкви утверждают, что были основаны одним или несколькими апостолами Иисуса , которые , как говорят, разошлись из Иерусалима где-то после распятия Иисуса , около 26–33 гг., возможно, следуя Великому поручению . Ранние христиане собирались в небольших частных домах, [2] известных как домашние церкви , но вся христианская община города также называлась « церковью » — греческое существительное ἐκκλησία ( ekklesia ) буквально означает «собрание», «собрание» или «конгрегация» [3] [4], но переводится как « церковь » в большинстве английских переводов Нового Завета .

Многие ранние христиане были торговцами и другими людьми, имевшими практические причины для путешествий в Малую Азию , Аравию , на Балканы , Ближний Восток , в Северную Африку и другие регионы. [5] [6] [7] Более 40 таких общин были основаны к 100 году, [6] [7] многие в Анатолии, также известной как Малая Азия, например, Семь церквей Азии . К концу первого века христианство уже распространилось в Риме, Армении, Греции и Сирии, послужив основой для обширного распространения христианства , в конечном итоге по всему миру.

Христианство возникло как небольшая секта в иудаизме Второго Храма [8], форме иудаизма, названной в честь Второго Храма, построенного около 516 г. до н. э. после вавилонского плена . В то время как Персидская империя разрешила евреям вернуться на свою родину в Иудее , там больше не было местной еврейской монархии. Вместо этого политическая власть перешла к первосвященнику , который служил посредником между еврейским народом и империей. Это положение сохранялось и после того, как регион был завоеван Александром Македонским (356–323 гг. до н. э.). [9] После смерти Александра регионом правил Птолемеевский Египет ( ок. 301 – ок. 200 г. до н. э. ), а затем империя Селевкидов ( ок. 200 – ок. 142 г. до н. э. ). Антиеврейская политика Антиоха IV Эпифана ( годы правления 175–164 до н. э. ) спровоцировала восстание Маккавеев в 167 г. до н. э., которое завершилось созданием независимой Иудеи под властью Хасмонеев , правивших как цари и первосвященники. Эта независимость продлится до 63 г. до н. э., когда Иудея станет зависимым государством Римской империи . [10]

Центральные принципы иудаизма Второго Храма вращались вокруг монотеизма и веры в то, что евреи были избранным народом . Как часть своего завета с Богом , евреи были обязаны соблюдать Тору . Взамен им была дана земля Израиля и город Иерусалим , где Бог обитал в Храме. Апокалиптическая и мудрая литература оказала большое влияние на иудаизм Второго Храма. [11]

Завоевания Александра положили начало эллинистическому периоду , когда Древний Ближний Восток подвергся эллинизации (распространению греческой культуры ). После этого иудаизм стал культурно и политически частью эллинистического мира; однако эллинистический иудаизм был сильнее среди евреев диаспоры, чем среди тех, кто жил в земле Израиля. [12] Евреи диаспоры говорили на греческом койне , а евреи Александрии создали греческий перевод еврейской Библии, названный Септуагинтой . Септуагинта была переводом Ветхого Завета, который использовали ранние христиане. [13] Евреи диаспоры продолжали совершать паломничества в Храм , но они начали создавать местные религиозные учреждения, называемые синагогами, еще в 3 веке до н. э. [14]

Восстание Маккавеев привело к разделению иудаизма на конкурирующие секты с различными теологическими и политическими целями, [15] каждая из которых заняла разные позиции по отношению к эллинизации. Основными сектами были саддукеи , фарисеи и ессеи . [16] Саддукеи были в основном иерусалимскими аристократами, намеревавшимися сохранить контроль над еврейской политикой и религией. [17] Религия саддукеев была сосредоточена на Храме и его ритуалах. Фарисеи подчеркивали личное благочестие и толковали Тору таким образом, чтобы обеспечить религиозное руководство для повседневной жизни. В отличие от саддукеев, фарисеи верили в воскресение мертвых и загробную жизнь. Ессеи отвергали храмовое поклонение, которое, по их мнению, было осквернено нечестивыми священниками. Они были частью более широкого апокалиптического движения в иудаизме, которое верило, что конец света близок, когда Бог восстановит Израиль. [18] Римское правление обострило эти религиозные противоречия и привело к тому, что радикальные зелоты отделились от фарисеев. Территории римской Иудеи и Галилеи часто были обеспокоены восстаниями и мессианскими претендентами . [19]

Мессия ( иврит : meshiach ) означает «помазанник» и используется в Ветхом Завете для обозначения еврейских царей и в некоторых случаях священников и пророков , чей статус символизировался помазанием святым маслом помазания . Этот термин больше всего ассоциируется с царем Давидом , которому Бог обещал вечное царство ( 2 Царств 7:11–17 ). После разрушения царства и рода Давида это обещание было подтверждено пророками Исайей , Иеремией и Иезекиилем , которые предвидели будущего царя из Дома Давида , который установит и будет править идеализированным царством. [20]

В период Второго Храма не было единого мнения о том, кем будет мессия или что он будет делать. [21] Чаще всего его представляли сыном Давида конца времен, который будет заниматься «исполнением суда, победой над врагами Бога, правлением над восстановленным Израилем [и] установлением вечного мира». [22] Однако были и другие виды предложенных мессианских фигур — совершенный священник или небесный Сын Человеческий , который осуществит воскрешение мертвых и последний суд . [23] [24]

Христианство сосредоточено на жизни и служении Иисуса из Назарета , который жил около 4 г. до н. э. — около 33 г. н. э . Иисус не оставил собственных писаний, и большая часть информации о нем исходит из ранних христианских писаний, которые теперь являются частью Нового Завета . Самыми ранними из них являются послания Павла , письма, написанные различным христианским общинам апостолом Павлом в 50-х годах нашей эры. Четыре канонических евангелия от Матфея ( около 80 г. н. э . — около 90 г. н. э. ), Марка ( около 70 г. н. э . ), Луки ( около 80 г. н. э . — около 90 г. н. э . ) и Иоанна (написанное в конце I века) являются древними биографиями жизни Иисуса. [25]

Иисус вырос в Назарете , городе в Галилее . Он был крещен в реке Иордан Иоанном Крестителем . Иисус начал свое собственное служение, когда ему было около 30 лет, примерно во время ареста и казни Крестителя . Послание Иисуса было сосредоточено на пришествии Царства Божьего (в иудейской эсхатологии будущее, когда Бог активно правит миром в справедливости, милосердии и мире). Иисус призывал своих последователей покаяться в подготовке к пришествию Царства. Его этические учения включали любовь к врагам своим ( Матфея 5:44 ; Луки 6:28–35 ), раздачу милостыни и тайный пост ( Матфея 6:4–18 ), не служение Богу и маммоне ( Матфея 6:24 ; Луки 16:13 ) и не судить других ( Матфея 7:1–2 ; Луки 6:37–38). Эти учения подчеркиваются в Нагорной проповеди и Молитве Господней . Иисус выбрал 12 учеников , которые представляли 12 колен Израиля (10 из которых были «потеряны» к тому времени), чтобы символизировать полное восстановление Израиля, которое будет достигнуто через него. [26]

Евангельские рассказы дают представление о том, во что верили ранние христиане относительно Иисуса. [27] Как Христос или «Помазанник» (греч. Christos ), Иисус идентифицируется как исполнение мессианских пророчеств в еврейских писаниях. Через рассказы о его чудесном непорочном зачатии евангелия представляют Иисуса как Сына Божьего . [28] Евангелия описывают чудеса Иисуса , которые служили для подтверждения его послания и раскрывают предвкушение грядущего царства. [29] Евангельские рассказы завершаются описанием распятия и воскресения Иисуса , что в конечном итоге привело к его вознесению на небеса . Победа Иисуса над смертью стала центральным верованием христианства. [30] По словам историка Диармейда Маккалоха : [31]

То ли из-за массового заблуждения, то ли из-за колоссального акта принятия желаемого за действительное, то ли из-за свидетельства силы, превосходящей любое определение, известное западному историческому анализу, те, кто знал Иисуса при жизни и испытал сокрушительное разочарование от его смерти, провозгласили, что он все еще жив, что он все еще любит их и что он должен вернуться на землю с Небес, на которые он сейчас вошел, чтобы любить и спасти от гибели всех, кто признал его Господом.

Для его последователей смерть Иисуса открыла Новый Завет между Богом и его народом. [32] Апостол Павел в своих посланиях учил, что Иисус делает спасение возможным. Через веру верующие испытывают единение с Иисусом и оба разделяют его страдания и надежду на его воскресение. [33]

Хотя они не предоставляют новой информации, нехристианские источники подтверждают определенную информацию, найденную в евангелиях. Иудейский историк Иосиф Флавий ссылался на Иисуса в своих «Иудейских древностях», написанных около 95 г. н. э . Абзац, известный как Testimonium Flavianum , дает краткое изложение жизни Иисуса, но оригинальный текст был изменен христианской интерполяцией . [34] Первым римским автором, упомянувшим Иисуса, был Тацит ( около 56 г. н. э . – около 120 г. н. э. ), который писал, что христиане «взяли свое имя от Христа , который был казнен в правление Тиберия прокуратором Понтием Пилатом» . [35]

Десятилетия после распятия Иисуса известны как Апостольский век, потому что ученики (также известные как апостолы ) были еще живы. [36] Важными христианскими источниками для этого периода являются послания Павла и Деяния апостолов . [37]

После смерти Иисуса его последователи основали христианские группы в городах, таких как Иерусалим. [36] Движение быстро распространилось в Дамаске и Антиохии , столице Римской Сирии и одном из важнейших городов империи. [38] Ранние христиане называли себя братьями, учениками или святыми , но именно в Антиохии, согласно Деяниям 11:26, их впервые стали называть христианами (греч. Christianoi ). [39]

Согласно Новому Завету, апостол Павел основал христианские общины по всему Средиземноморью. [36] Известно, что он также провел некоторое время в Аравии. После проповеди в Сирии он обратил свое внимание на города Малой Азии . К началу 50-х годов он отправился в Европу, где остановился в Филиппах , а затем отправился в Фессалоники в Римской Македонии . Затем он переехал в материковую Грецию, проведя время в Афинах и Коринфе . Находясь в Коринфе, Павел написал свое Послание к Римлянам , указав, что в Риме уже были христианские группы . Некоторые из этих групп были основаны миссионерскими соратниками Павла Прискиллой, Акилой и Эпинетом . [40]

Социальные и профессиональные сети играли важную роль в распространении религии, поскольку члены приглашали заинтересованных посторонних на тайные христианские собрания (греч. ekklēsia ), которые встречались в частных домах (см. домашняя церковь ). Коммерция и торговля также сыграли свою роль в распространении христианства, поскольку христианские торговцы путешествовали по делам. Христианство привлекало маргинализированные группы (женщин, рабов) своим посланием о том, что «во Христе нет ни иудея, ни язычника, ни мужеского пола, ни женского, ни раба, ни свободного» ( Галатам 3:28 ). Христиане также оказывали социальные услуги бедным, больным и вдовам. [41] Женщины активно способствовали христианской вере в качестве учеников, миссионеров и т. д. из-за большого принятия раннего христианства.

Историк Кит Хопкинс подсчитал, что к 100 году нашей эры насчитывалось около 7000 христиан (около 0,01 процента населения Римской империи в 60 миллионов человек). [42] Отдельные христианские группы поддерживали связь друг с другом посредством писем, визитов странствующих проповедников и обмена общими текстами, некоторые из которых позже были собраны в Новом Завете. [36]

Иерусалим был первым центром христианской церкви согласно Книге Деяний . [44] Апостолы жили и учили там некоторое время после Пятидесятницы. [45] Согласно Деяниям, раннюю церковь возглавляли апостолы, главными из которых были Петр и Иоанн . Когда Петр покинул Иерусалим после того, как Ирод Агриппа I попытался убить его, Иаков, брат Иисуса , появляется как лидер Иерусалимской церкви. [45] Климент Александрийский ( ок. 150–215 гг. н. э. ) назвал его епископом Иерусалима . [45] Петр, Иоанн и Иаков были коллективно признаны тремя столпами церкви ( Галатам 2:9 ). [46]

В этот ранний период христианство все еще было еврейской сектой. Христиане в Иерусалиме соблюдали еврейскую субботу и продолжали поклоняться в Храме. В память о воскресении Иисуса они собирались в воскресенье на причастие . Первоначально христиане соблюдали еврейский обычай поститься по понедельникам и четвергам. Позже христианские постные дни переместились на среду и пятницу (см. Пятничный пост ) в память о предательстве Иуды и распятии. [47]

Иаков был убит по приказу первосвященника в 62 г. н. э. Его преемником на посту главы Иерусалимской церкви стал Симеон , другой родственник Иисуса. [48] Во время Первой иудейско-римской войны ( 66–73 гг. н. э.) Иерусалим и Храм были разрушены после жестокой осады в 70 г. н. э. [45] Пророчества о разрушении Второго Храма встречаются в синоптических евангелиях , [49] в частности в « Рассуждении на Оливковой горе» .

Согласно традиции, записанной Евсевием и Епифанием Саламинским , Иерусалимская церковь бежала в Пеллу во время начала Первого иудейского восстания . [50] [51] Церковь вернулась в Иерусалим к 135 году нашей эры, но беспорядки серьезно ослабили влияние Иерусалимской церкви на более широкую христианскую церковь . [48]

Иерусалим был первым центром христианской церкви согласно Книге Деяний . [44] Апостолы жили и учили там некоторое время после Пятидесятницы . [45] Иаков Справедливый, брат Иисуса, был лидером ранней христианской общины в Иерусалиме, и его другие родственники , вероятно, занимали руководящие должности в окрестностях после разрушения города до его восстановления как Элии Капитолина примерно в 130 году н. э. , когда все евреи были изгнаны из Иерусалима. [45]

Первые язычники, ставшие христианами, были богобоязненными , людьми, которые верили в истинность иудаизма, но не стали прозелитами (см. Корнелий Сотник ). [52] Когда язычники присоединились к молодому христианскому движению, вопрос о том, должны ли они принять иудаизм и соблюдать Тору (например, законы о еде , мужское обрезание и соблюдение субботы), породил различные ответы. Некоторые христиане требовали полного соблюдения Торы и требовали, чтобы обращенные язычники становились евреями. Другие, такие как Павел, считали, что Тора больше не является обязательной из-за смерти и воскресения Иисуса. Посередине были христиане, которые считали, что язычники должны следовать некоторым частям Торы, но не всем. [53]

В 48–50 гг. н. э . Варнава и Павел отправились в Иерусалим, чтобы встретиться с тремя столпами церкви : [44] [54] Иаковом Справедливым, Петром и Иоанном . [44] [55] Позднее названная Иерусалимским собором , по словам христиан-паулистов , эта встреча (помимо прочего) подтвердила законность евангелизаторской миссии Варнавы и Павла среди язычников . Она также подтвердила, что обращенные язычники не обязаны следовать Закону Моисееву , [55] особенно практике мужского обрезания , [55] которая осуждалась как отвратительная и отталкивающая в греко-римском мире в период эллинизации Восточного Средиземноморья , [61] и особенно осуждалась в классической цивилизации древними греками и римлянами , которые положительно ценили крайнюю плоть . [63] Предполагается, что получившийся Апостольский указ в Деяниях 15 соответствует семи законам Ноя, найденным в Ветхом Завете . [67] Однако современные ученые оспаривают связь между Деяниями 15 и семью законами Ноя. [66] Примерно в тот же период времени раввинские еврейские юридические власти сделали свое требование обрезания для еврейских мальчиков еще строже. [68]

Основной вопрос, который был рассмотрен, касался требования обрезания , как сообщает автор Деяний, но возникли и другие важные вопросы, как указывает Апостольский указ. [55] Спор возник между теми, кто, например, был последователем «Столпов Церкви» во главе с Иаковом , который считал, следуя его толкованию Великого поручения , что церковь должна соблюдать Тору , т. е. правила традиционного иудаизма, [1] и апостолом Павлом , который называл себя «Апостолом язычников», [69] который считал, что такой необходимости нет. [72] Главной заботой апостола Павла, которую он впоследствии выразил более подробно в своих посланиях, направленных ранним христианским общинам в Малой Азии , было включение язычников в Новый Завет Бога , посылая сообщение о том, что вера во Христа достаточна для спасения . [73] ( См. также : Суперсессионизм , Новый Завет , Антиномианизм , Эллинистический иудаизм , Апостол Павел и иудаизм ).

Однако Иерусалимский собор не положил конец спору. [55] Есть указания на то, что Иаков все еще считал, что Тора обязательна для иудеев-христиан. В Послании к Галатам 2:11-14 описываются «люди от Иакова», заставившие Петра и других иудеев-христиан в Антиохии прервать общение за столом с язычниками. [76] ( См. также : Инцидент в Антиохии ). Джоэл Маркус, профессор христианского происхождения, предполагает, что позиция Петра могла находиться где-то между Иаковом и Павлом, но что он, вероятно, больше склонялся к Иакову. [77] Это начало раскола между иудейским христианством и языческим (или Павловым) христианством . Хотя иудейское христианство оставалось важным в течение следующих нескольких столетий, в конечном итоге оно было отодвинуто на обочину, поскольку языческое христианство стало доминирующим. Иудейскому христианству также противостоял ранний раввинистический иудаизм , преемник фарисеев. [78] Когда Петр покинул Иерусалим после того, как Ирод Агриппа I попытался убить его, Иаков предстает как главный авторитет ранней христианской церкви. [45] Климент Александрийский ( ок. 150–215 гг. н. э. ) называл его епископом Иерусалимским . [45] Историк церкви II века Гегесипп писал, что синедрион предал его мученической смерти в 62 г. н. э. [45]

В 66 году нашей эры евреи восстали против Рима . [45] После жестокой осады Иерусалим пал в 70 году нашей эры . [45] Город, включая еврейский храм, был разрушен, а население было в основном убито или выселено. [45] Согласно преданию, записанному Евсевием и Епифанием Саламинским , иерусалимская церковь бежала в Пеллу во время начала Первого еврейского восстания . [50] [51] По словам Епифания Саламинского, [79] [ необходим лучший источник ] Тайная вечеря просуществовала по крайней мере до визита Адриана в 130 году нашей эры . Рассеянное население выжило. [45] Синедрион переехал в Ямнию . [80] Пророчества о разрушении Второго храма встречаются в синоптических Евангелиях , [49] в частности, в речи Иисуса на Оливковой горе .

Римляне негативно относились к ранним христианам. Римский историк Тацит писал, что христиане презирали за их «мерзости» и «ненависть к человечеству». [81] Убеждение, что христиане ненавидели человечество, могло относиться к их отказу участвовать в общественной деятельности, связанной с языческим поклонением, — сюда входило большинство общественных мероприятий, таких как театр , армия, спорт и классическая литература . Они также отказывались поклоняться римскому императору , как и иудеи. Тем не менее, римляне были более снисходительны к евреям по сравнению с христианами-язычниками. Некоторые антихристианские римляне еще больше различали иудеев и христиан, утверждая, что христианство было «отступничеством» от иудаизма. Цельс , например, считал иудейских христиан лицемерами за то, что они утверждали, что приняли свое еврейское наследие. [82]

Император Нерон преследовал христиан в Риме, которых он обвинял в начале Великого пожара 64 г. н. э. Возможно, что Петр и Павел были в Риме и были замучены в это время. Нерон был низложен в 68 г. н. э., и гонения на христиан прекратились. При императорах Веспасиане ( годы правления 69–79 ) и Тите ( годы правления 79–81 ) христиане в значительной степени игнорировались римским правительством. Император Домициан ( годы правления 81–96 ) санкционировал новые гонения на христиан. Именно в это время Иоанном Патмосским была написана Книга Откровения . [83]

Во II веке римский император Адриан перестроил Иерусалим как языческий город и переименовал его в Элию Капитолину , [84] воздвигнув статуи Юпитера и себя на месте бывшего еврейского храма, Храмовой горы . В 132–136 годах нашей эры Бар-Кохба возглавил неудачное восстание как еврейский претендент на Мессию , но христиане отказались признать его таковым. Когда Бар-Кохба был побежден, Адриан запретил евреям входить в город, за исключением дня Тиша бе-Ав , таким образом, последующие епископы Иерусалима впервые были язычниками («необрезанными»). [85]

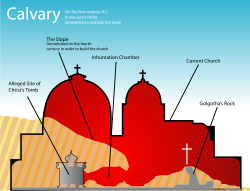

Общее значение Иерусалима для христиан вошло в период упадка во время гонений на христиан в Римской империи . Согласно Евсевию , христиане Иерусалима бежали в Пеллу , в Декаполисе ( Трансиордании ), в начале Первой иудейско-римской войны в 66 г. н. э. [86] Епископы Иерусалима стали суффраганами (подчиненными) епископа -митрополита в соседней Кесарии, [87] [ необходим лучший источник ] Интерес к Иерусалиму возобновился с паломничеством римской императрицы Елены в Святую Землю ( ок. 326–328 гг. н. э. ). По словам церковного историка Сократа Константинопольского , [88] Елена (при содействии епископа Макария Иерусалимского ) утверждала, что нашла крест Христа , после того как убрала храм Венеры (приписываемый Адриану), который был построен на этом месте. Иерусалим получил особое признание в каноне VII Первого Никейского собора в 325 г. н. э. [89] Традиционной датой основания Братства Гроба Господня (охраняющего христианские святые места на Святой Земле) является 313 год, что соответствует дате Миланского эдикта , обнародованного римским императором Константином Великим , который легализовал христианство в Римской империи. Позднее Иерусалим был назван одним из Пентархии , но это никогда не было принято Римской церковью. [90] [91] ( См. также : Раскол Востока и Запада#Перспективы примирения ).

Антиохия (современная Антакья , Турция) была столицей римской провинции Сирия и центром греческой культуры в Восточном Средиземноморье , а также ключевым местом торговли, что сделало ее третьим по значимости городом Римской империи. [92] В Книге Деяний говорится, что именно в Антиохии последователи Иисуса впервые были названы христианами; [93] это было также место инцидента в Антиохии , описанного в Послании к Галатам . Это было место ранней церкви, которая традиционно считается основанной Петром; более поздние традиции также приписывали роль епископа Антиохийского, как впервые занимаемого Петром. [94] Евангелие от Матфея и Апостольские постановления, возможно, были написаны там. Отец церкви Игнатий Антиохийский был ее третьим епископом. Школа Антиохии, основанная в 270 году, была одним из двух основных центров раннего церковного обучения. Кюретонские Евангелия и сирийский Синайский текст — два ранних (до Пешитты ) типа текстов Нового Завета, связанных с сирийским христианством . Это был один из трех, чьи епископы были признаны на Первом Никейском соборе (325) как осуществляющие юрисдикцию над прилегающими территориями. [95]

Александрия , в дельте Нила , была основана Александром Великим . Ее знаменитые библиотеки были центром эллинистического образования. Там начался перевод Ветхого Завета на Септуагинту , а александрийский тип текста признан учеными одним из самых ранних типов Нового Завета. В нем проживало значительное еврейское население , из которых Филон Александрийский , вероятно, является его самым известным автором. [96] Он создал превосходное писание и выдающихся отцов церкви, таких как Климент, Ориген и Афанасий; [97] [ необходим лучший источник ] также заслуживают внимания близлежащие отцы-пустынники . К концу эпохи Александрия, Рим и Антиохия получили власть над близлежащими митрополитами . Никейский собор в каноне VI подтвердил традиционную власть Александрии над Египтом, Ливией и Пентаполисом (Северная Африка) ( Египетская епархия ) и, вероятно, предоставил Александрии право объявлять всемирную дату для соблюдения Пасхи [98] (см. также пасхальные споры ). Однако некоторые полагают, что Александрия была не только центром христианства, но и центром гностических сект, основанных на христианстве.

Традиция апостола Иоанна была сильна в Анатолии ( ближневосточная часть современной Турции, западная часть называлась римской провинцией Азия ). Авторство Иоанновых трудов традиционно и правдоподобно произошло в Эфесе , около 90–110 гг., хотя некоторые ученые утверждают, что происхождение из Сирии. [99] Это включает в себя Книгу Откровения , хотя современные исследователи Библии считают, что ее автором был другой Иоанн, Иоанн с Патмоса (греческий остров примерно в 30 милях от побережья Анатолии), который упоминает Семь церквей Азии . Согласно Новому Завету, апостол Павел был из Тарса (в юго-центральной Анатолии), и его миссионерские путешествия были в основном в Анатолии. Первое послание Петра (1:1–2) адресовано анатолийским регионам. На юго-восточном берегу Черного моря Понт был греческой колонией, упомянутой трижды в Новом Завете. Жители Понта были одними из первых обращенных в христианство. Плиний, правитель в 110 году , в своих письмах обращался к христианам в Понте. Из сохранившихся писем Игнатия Антиохийского, считающихся подлинными , пять из семи адресованы анатолийским городам, шестое — Поликарпу . Смирна была родиной Поликарпа, епископа, который, как сообщается, знал апостола Иоанна лично, и, вероятно, также его ученика Иринея . Папий Иерапольский , как полагают, также был учеником апостола Иоанна. Во II веке Анатолия была домом квартодециманизма , монтанизма , Маркиона Синопского и Мелитона Сардийского, который записал ранний христианский библейский канон . После кризиса третьего века Никомедия стала столицей Восточной Римской империи в 286 году. Анкирский собор состоялся в 314 году. В 325 году император Константин созвал первый христианский вселенский собор в Никее , а в 330 году перенес столицу объединенной империи в Византий (также ранний христианский центр и прямо через Босфор от Анатолии , позже названной Константинополем ), именуемый Византийской империей ., который продолжался до 1453 года. [100] [ необходим лучший источник ] Первые семь Вселенских соборов проводились либо в Западной Анатолии, либо по ту сторону Босфора в Константинополе.

Кесария , на берегу моря к северо-западу от Иерусалима, сначала Кесария Приморская , затем после 133 Кесария Палестинская , была построена Иродом Великим , около 25–13 гг. до н. э., и была столицей провинции Иудея (6–132 гг.), а затем Палестина Прима . Именно там Петр крестил сотника Корнелия , считающегося первым обращенным из язычников. Павел искал там убежища, однажды остановившись в доме Филиппа Евангелиста , а затем будучи заключенным там в течение двух лет (предположительно 57–59 гг.). В Апостольских постановлениях (7.46) говорится, что первым епископом Кесарии был Закхей Мытарь .

После осады Иерусалима Адрианом (ок. 133 г.) Кесария стала митрополией , а епископ Иерусалима был одним из ее «викарных епископов» (подчиненных). [101] [ необходим лучший источник ] Ориген (ум. 254 г.) составил там свою Гексаплу , и там была знаменитая библиотека и богословская школа , святой Памфил (ум. 309 г.) был известным ученым-священником. Святой Григорий Чудотворец (ум. 270 г.), святой Василий Великий (ум. 379 г.) и святой Иероним (ум. 420 г.) посещали и учились в библиотеке, которая позже была разрушена, вероятно, персами в 614 г. или сарацинами около 637 г. [102] [ необходим лучший источник ] Первый крупный историк церкви Евсевий Кесарийский был епископом, около 314–339 гг. FJA Hort и Adolf von Harnack утверждали, что Никейский символ веры возник в Кесарии. Кесарийский тип текста признан многими текстологами одним из самых ранних новозаветных типов.

Пафос был столицей острова Кипр в римские годы и резиденцией римского полководца. В 45 г. н. э. апостолы Павел и Варнава , который согласно Деяниям 4:36 был «уроженцем Кипра», прибыли на Кипр и достигли Пафоса, проповедуя послание Иисуса, см. также Деяния 13:4–13. Согласно Деяниям, апостолы подвергались преследованиям со стороны римлян, но в конечном итоге им удалось убедить римского полководца Сергия Павла отказаться от своей старой религии в пользу христианства. Варнава традиционно считается основателем Кипрской православной церкви. [103] [ требуется лучший источник ]

Дамаск является столицей Сирии и претендует на звание старейшего непрерывно населенного города в мире. Согласно Новому Завету, апостол Павел был обращен по дороге в Дамаск . В трех рассказах (Деяния 9:1–20, 22:1–22, 26:1–24) он описывается как ведомый теми, с кем он путешествовал, ослепленный светом, в Дамаск, где его зрение было восстановлено учеником по имени Анания (который, как полагают, был первым епископом Дамаска) [ нужна цитата ], затем он был крещен .

Фессалоники , главный северный греческий город, где, как полагают, христианство было основано Павлом , таким образом, Апостольский престол , и окружающие регионы Македонии , Фракии и Эпира , которые также простираются в соседние балканские государства Албанию и Болгарию , были ранними центрами христианства. Следует отметить Послания Павла к Фессалоникийцам и Филиппам , которые часто считаются первым контактом христианства с Европой. [104] [ необходим лучший источник ] Апостольский отец Поликарп написал письмо к Филиппийцам , около 125 г.

Никополь был городом в римской провинции Эпир Ветус , сегодня руины в северной части западного побережья Греции. В Послании к Титу Павел сказал, что он намеревался пойти туда. [105] Возможно, что среди его населения были некоторые христиане. Согласно Евсевию , Ориген (ок. 185–254) останавливался там на некоторое время [106]

Древний Коринф , сегодня руины около современного Коринфа в южной Греции, был ранним центром христианства. Согласно Деяниям Апостолов , Павел оставался в Коринфе восемнадцать месяцев, чтобы проповедовать. [107] Первоначально он оставался с Акилой и Прискиллой , а позже к нему присоединились Сила и Тимофей . После того, как он покинул Коринф, Прискилла послала Аполлона из Эфеса , чтобы заменить его. [ нужна цитата ] Павел возвращался в Коринф по крайней мере один раз. [ нужна цитата ] Он написал Первое послание к Коринфянам из Эфеса примерно в 54-55 годах, в котором основное внимание уделялось сексуальной безнравственности, разводам, судебным искам и воскрешениям. [108] Второе послание к Коринфянам из Македонии было написано около 56 года как четвертое письмо, в котором обсуждались его предлагаемые планы на будущее, инструкции, единство и его защита апостольской власти. [109] Самые ранние свидетельства главенства Римской церкви можно увидеть в Первом послании Климента, написанном Коринфской церкви и датируемом примерно 96 годом. [ необходима цитата ] Епископами Коринфа были Аполлон, Сосфен и Дионисий . [110] [ необходим лучший источник ]

Афины , столицу и крупнейший город Греции, посетил Павел. Вероятно, он путешествовал морем, прибыв в Пирей , гавань Афин, из Верии Македонской около 53 года. [ необходима цитата ] Согласно Деяниям 17 , когда он прибыл в Афины, он немедленно послал за Силой и Тимофеем, которые остались в Верии. [ необходима цитата ] Ожидая их, Павел исследовал Афины и посетил синагогу, так как там была местная еврейская община . Христианская община быстро образовалась в Афинах, хотя изначально она, возможно, была невелика. [ необходима цитата ] Распространенная традиция определяет Ареопагита как первого епископа христианской общины в Афинах, в то время как другая традиция упоминает Иерофея Фесмофета . [ необходима цитата ] Последующие епископы не все были афинского происхождения: считалось, что Наркисс был родом из Палестины, а Публий — с Мальты. [ необходима цитата ] Квадрат известен извинениями, адресованными императору Адриану во время его визита в Афины, что внесло вклад в раннюю христианскую литературу. [ необходима цитата ] Аристид и Афинагор также писали извинения в это время. [ необходима цитата ] Ко второму веку в Афинах, вероятно, существовала значительная христианская община, поскольку Гигиен , епископ Рима, написал письмо общине в Афинах в 139 году. [ необходима цитата ]

Гортина на Крите была союзницей Рима и, таким образом, стала столицей римской Креты и Киренаики . [ нужна цитата ] Считается, что первым епископом был Святой Тит . Город был разграблен пиратом Абу Хафсом в 828 году. [ нужна цитата ]

Paul the Apostle preached in Macedonia, and also in Philippi, located in Thrace on the Thracian Sea coast. According to Hippolytus of Rome, Andrew the Apostle preached in Thrace, on the Black Sea coast and along the lower course of the Danube River. The spread of Christianity among the Thracians and the emergence of centers of Christianity like Serdica (present day Sofia), Philippopolis (present day Plovdiv) and Durostorum (present day Silistra) was likely to have begun with these early Apostolic missions.[111] The first Christian monastery in Europe was founded in Thrace in 344 by Saint Athanasius near modern-day Chirpan, Bulgaria, following the Council of Serdica.[112]

Cyrene and the surrounding region of Cyrenaica or the North African "Pentapolis", south of the Mediterranean from Greece, the northeastern part of modern Libya, was a Greek colony in North Africa later converted to a Roman province. In addition to Greeks and Romans, there was also a significant Jewish population, at least up to the Kitos War (115–117). According to Mark 15:21, Simon of Cyrene carried Jesus' cross. Cyrenians are also mentioned in Acts 2:10, 6:9, 11:20, 13:1. According to Byzantine legend, the first bishop was Lucius, mentioned in Acts 13:1.[citation needed]

Exactly when Christians first appeared in Rome is difficult to determine. The Acts of the Apostles claims that the Jewish Christian couple Priscilla and Aquila had recently come from Rome to Corinth when, in about the year 50, Paul reached the latter city,[113] indicating that belief in Jesus in Rome had preceded Paul.

Historians consistently consider Peter and Paul to have been martyred in Rome under the reign of Nero[114][115][116] in 64, after the Great Fire of Rome which, according to Tacitus, the Emperor blamed on the Christians.[117][118] In the second century Irenaeus of Lyons, reflecting the ancient view that the church could not be fully present anywhere without a bishop, recorded that Peter and Paul had been the founders of the Church in Rome and had appointed Linus as bishop.[119][120]

However, Irenaeus does not say that either Peter or Paul was "bishop" of the Church in Rome and several historians have questioned whether Peter spent much time in Rome before his martyrdom. While the church in Rome was already flourishing when Paul wrote his Epistle to the Romans to them from Corinth (c. 58)[121] he attests to a large Christian community already there[118] and greets some fifty people in Rome by name,[122] but not Peter, whom he knew. There is also no mention of Peter in Rome later during Paul's two-year stay there in Acts 28, about 60–62. Most likely he did not spend any major time at Rome before 58 when Paul wrote to the Romans, and so it may have been only in the 60s and relatively shortly before his martyrdom that Peter came to the capital.[123]

Oscar Cullmann sharply rejected the claim that Peter began the papal succession,[124] and concludes that while Peter was the original head of the apostles, Peter was not the founder of any visible church succession.[124][125]

The original seat of Roman imperial power soon became a center of church authority, grew in power decade by decade, and was recognized during the period of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, when the seat of government had been transferred to Constantinople, as the "head" of the church.[126]

Rome and Alexandria, which by tradition held authority over sees outside their own province,[127] were not yet referred to as patriarchates.[128]

The earliest Bishops of Rome were all Greek-speaking, the most notable of them being: Pope Clement I (c. 88–97), author of an Epistle to the Church in Corinth; Pope Telesphorus (c. 126–136), probably the only martyr among them; Pope Pius I (c. 141–154), said by the Muratorian fragment to have been the brother of the author of the Shepherd of Hermas; and Pope Anicetus (c. 155–160), who received Saint Polycarp and discussed with him the dating of Easter.[118]

Pope Victor I (189–198) was the first ecclesiastical writer known to have written in Latin; however, his only extant works are his encyclicals, which would naturally have been issued in Latin and Greek.[129]

Greek New Testament texts were translated into Latin early on, well before Jerome, and are classified as the Vetus Latina and Western text-type.

During the 2nd century, Christians and semi-Christians of diverse views congregated in Rome, notably Marcion and Valentinius, and in the following century there were schisms connected with Hippolytus of Rome and Novatian.[118]

The Roman church survived various persecutions. Among the prominent Christians executed as a result of their refusal to perform acts of worship to the Roman gods as ordered by emperor Valerian in 258 were Cyprian, bishop of Carthage.[130] The last and most severe of the imperial persecutions was that under Diocletian in 303; they ended in Rome, and the West in general, with the accession of Maxentius in 306.

Carthage, in the Roman province of Africa, south of the Mediterranean from Rome, gave the early church the Latin fathers Tertullian[131] (c. 120 – c. 220) and Cyprian[132] (d. 258). Carthage fell to Islam in 698.

The Church of Carthage thus was to the Early African church what the Church of Rome was to the Catholic Church in Italy.[133] The archdiocese used the African Rite, a variant of the Western liturgical rites in Latin language, possibly a local use of the primitive Roman Rite. Famous figures include Saint Perpetua, Saint Felicitas, and their Companions (died c. 203), Tertullian (c. 155–240), Cyprian (c. 200–258), Caecilianus (floruit 311), Saint Aurelius (died 429), and Eugenius of Carthage (died 505). Tertullian and Cyprian are considered Latin Church Fathers of the Latin Church. Tertullian, a theologian of part Berber descent, was instrumental in the development of trinitarian theology, and was the first to apply Latin language extensively in his theological writings. As such, Tertullian has been called "the father of Latin Christianity"[134][135] and "the founder of Western theology."[136] Carthage remained an important center of Christianity, hosting several councils of Carthage.

The Mediterranean coast of France and the Rhone valley, then part of Roman Gallia Narbonensis, were early centers of Christianity. Major Christian communities were found in Arles, Avignon, Vienne, Lyon, and Marseille (the oldest city in France). The Persecution in Lyon occurred in 177. The Apostolic Father Irenaeus from Smyrna of Anatolia was Bishop of Lyon near the end of the 2nd century and he claimed Saint Pothinus was his predecessor. The Council of Arles in 314 is considered a forerunner of the ecumenical councils. The Ephesine theory attributes the Gallican Rite to Lyon.

The ancient Roman city of Aquileia at the head of the Adriatic Sea, today one of the main archaeological sites of Northern Italy, was an early center of Christianity said to be founded by Mark before his mission to Alexandria. Hermagoras of Aquileia is believed to be its first bishop. The Aquileian Rite is associated with Aquileia.

It is believed that the Church of Milan in northwest Italy was founded by the apostle Barnabas in the 1st century. Gervasius and Protasius and others were martyred there. It has long maintained its own rite known as the Ambrosian Rite attributed to Ambrose (born c. 330) who was bishop in 374–397 and one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures of the 4th century. Duchesne argues that the Gallican Rite originated in Milan.

Syracuse was founded by Greek colonists in 734 or 733 BC, part of Magna Graecia. Syracuse is one of the first Christian communities established by Peter, preceded only by Antioch. Paul also preached in Syracuse. Historical evidence from the middle of the third century, during the time of Cyprian, suggests that Christianity was thriving in Syracuse, and the presence of catacombs provides clear indications of Christian activity in the second century as well. Across the Strait of Messina, Calabria on the mainland was also probably an early center of Christianity.[137][better source needed]

According to Acts, Paul was shipwrecked and ministered on an island which some scholars have identified as Malta (an island just south of Sicily) for three months during which time he is said to have been bitten by a poisonous viper and survived (Acts 27:39–42; Acts 28:1–11), an event usually dated c. AD 60. Paul had been allowed passage from Caesarea Maritima to Rome by Porcius Festus, procurator of Iudaea Province, to stand trial before the Emperor. Many traditions are associated with this episode, and catacombs in Rabat testify to an Early Christian community on the islands. According to tradition, Publius, the Roman Governor of Malta at the time of Saint Paul's shipwreck, became the first Bishop of Malta following his conversion to Christianity. After ruling the Maltese Church for thirty-one years, Publius was transferred to the See of Athens in 90 AD, where he was martyred in 125 AD. There is scant information about the continuity of Christianity in Malta in subsequent years, although tradition has it that there was a continuous line of bishops from the days of St. Paul to the time of Emperor Constantine.

Salona, the capital of the Roman province of Dalmatia on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea, was an early center of Christianity and today is a ruin in modern Croatia. Titus, a disciple of Paul, preached there. Some Christians suffered martyrdom.[citation needed]

Salona emerged as a center for the spread of Christianity, with Andronicus establishing the See of Syrmium (Mitrovica) in Pannonia, followed by those in Siscia and Mursia.[citation needed] The Diocletianic Persecution left deep marks in Dalmatia and Pannonia. Quirinus, bishop of Siscia, died a martyr in A.D. 303.[citation needed]

Seville was the capital of Hispania Baetica or the Roman province of southern Spain. The origin of the diocese of Seville can be traced back to Apostolic times, or at least to the first century AD.[citation needed] Gerontius, the bishop of Italica, near Hispalis (Seville), likely appointed a pastor for Seville.[citation needed] A bishop of Seville named Sabinus participated in the Council of Illiberis in 287.[citation needed] He was the bishop when Justa and Rufina were martyred in 303 for refusing to worship the idol Salambo.[citation needed] Prior to Sabinus, Marcellus is listed as a bishop of Seville in an ancient catalogue of prelates preserved in the "Codex Emilianensis".[citation needed] After the Edict of Milan in 313, Evodius became the bishop of Seville and undertook the task of rebuilding the churches that had been damaged.[citation needed] It is believed that he may have constructed the church of San Vicente, which could have been the first cathedral of Seville.[citation needed] Early Christianity also spread from the Iberian peninsula south across the Strait of Gibraltar into Roman Mauretania Tingitana, of note is Marcellus of Tangier who was martyred in 298.[citation needed]

Christianity reached Roman Britain by the third century of the Christian era, the first recorded martyrs in Britain being St. Alban of Verulamium and Julius and Aaron of Caerleon, during the reign of Diocletian (284–305). Gildas dated the faith's arrival to the latter part of the reign of Tiberius, although stories connecting it with Joseph of Arimathea, Lucius, or Fagan are now generally considered pious forgeries. Restitutus, Bishop of London, is recorded as attending the 314 Council of Arles, along with the Bishop of Lincoln and Bishop of York.

Christianisation intensified and evolved into Celtic Christianity after the Romans left Britain c. 410.

Christianity also spread beyond the Roman Empire during the early Christian period.

It is accepted that Armenia became the first country to adopt Christianity as its state religion. Although it has long been claimed that Armenia was the first Christian kingdom, according to some scholars this has relied on a source by Agathangelos titled "The History of the Armenians", which has recently been redated, casting some doubt.[138]

After becoming a Christianized nation, Armenia's former divine figure, Hayk, was labeled as "one of the giants" which brought down the divine status. Other originally known gods, such as Vahagn or Angegh, also had a change in status to kings.[139]

Christianity became the official religion of Armenia in 301,[140] when it was still illegal in the Roman Empire. According to church tradition,[141] the Armenian Apostolic Church was founded by Gregory the Illuminator of the late third – early fourth centuries after the conversion of Tiridates III. The church traces its origins to the missions of Bartholomew the Apostle and Thaddeus (Jude the Apostle) in the 1st century.

Tiridates III was the first Christian king in Armenia from 298 to 330.[142]

According to Orthodox tradition, Christianity was first preached in Georgia by the Apostles Simon and Andrew in the 1st century. It became the state religion of Kartli (Iberia) in 319. The conversion of Kartli to Christianity is credited to a Greek lady called St. Nino of Cappadocia. The Georgian Orthodox Church, originally part of the Church of Antioch, gained its autocephaly and developed its doctrinal specificity progressively between the 5th and 10th centuries. The Bible was also translated into Georgian in the 5th century, as the Georgian alphabet was developed for that purpose.

According to Eusebius' record, the apostles Thomas and Bartholomew were assigned to Parthia (modern Iran) and India.[143][144] By the time of the establishment of the Second Persian Empire (AD 226), there were bishops of the Church of the East in northwest India, Afghanistan and Baluchistan (including parts of Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan), with laymen and clergy alike engaging in missionary activity.[143]

An early third-century Syriac work known as the Acts of Thomas[143] connects the apostle's Indian ministry with two kings, one in the north and the other in the south. According to the Acts, Thomas was at first reluctant to accept this mission, but the Lord appeared to him in a night vision and compelled him to accompany an Indian merchant, Abbanes (or Habban), to his native place in northwest India. There, Thomas found himself in the service of the Indo-Parthian King, Gondophares. The Apostle's ministry resulted in many conversions throughout the kingdom, including the king and his brother.[143]

Thomas thereafter went south to Kerala and baptized the natives, whose descendants form the Saint Thomas Christians or the Syrian Malabar Nasranis.[145]

Piecing together the various traditions, the story suggests that Thomas left northwest India when invasion threatened, and traveled by vessel to the Malabar Coast along the southwestern coast of the Indian continent, possibly visiting southeast Arabia and Socotra en route, and landing at the former flourishing port of Muziris on an island near Cochin in 52. From there he preached the gospel throughout the Malabar Coast. The various churches he founded were located mainly on the Periyar River and its tributaries and along the coast. He preached to all classes of people and had about 170 converts, including members of the four principal castes. Later, stone crosses were erected at the places where churches were founded, and they became pilgrimage centres. In accordance with apostolic custom, Thomas ordained teachers and leaders or elders, who were reported to be the earliest ministry of the Malabar church.

Thomas next proceeded overland to the Coromandel Coast in southeastern India, and ministered in what is now Chennai (earlier Madras), where a local king and many people were converted. One tradition related that he went from there to China via Malacca in Malaysia, and after spending some time there, returned to the Chennai area.[146] Apparently his renewed ministry outraged the Brahmins, who were fearful lest Christianity undermine their social caste system. So according to the Syriac version of the Acts of Thomas, Mazdai, the local king at Mylapore, after questioning the Apostle condemned him to death about the year AD 72. Anxious to avoid popular excitement, the King ordered Thomas conducted to a nearby mountain, where, after being allowed to pray, he was then stoned and stabbed to death with a lance wielded by an angry Brahmin.[143][145]

Edessa, which was held by Rome from 116 to 118 and 212 to 214, but was mostly a client kingdom associated either with Rome or Persia, was an important Christian city. Shortly after 201 or even earlier, its royal house became Christian.[147]

Edessa (now Şanlıurfa) in northwestern Mesopotamia was from apostolic times the principal center of Syriac-speaking Christianity. it was the capital of an independent kingdom from 132 BC to AD 216, when it became tributary to Rome. Celebrated as an important centre of Greco-Syrian culture, Edessa was also noted for its Jewish community, with proselytes in the royal family. Strategically located on the main trade routes of the Fertile Crescent, it was easily accessible from Antioch, where the mission to the Gentiles was inaugurated. When early Christians were scattered abroad because of persecution, some found refuge at Edessa. Thus the Edessan church traced its origin to the Apostolic Age (which may account for its rapid growth), and Christianity even became the state religion for a time.

The Church of the East had its inception at a very early date in the buffer zone between the Parthian and Roman Empires in Upper Mesopotamia, known as the Assyrian Church of the East. The vicissitudes of its later growth were rooted in its minority status in a situation of international tension. The rulers of the Parthian Empire (250 BC – AD 226) were on the whole tolerant in spirit, and with the older faiths of Babylonia and Assyria in a state of decay, the time was ripe for a new and vital faith. The rulers of the Second Persian empire (226–640) also followed a policy of religious toleration to begin with, though later they gave Christians the same status as a subject race. However, these rulers also encouraged the revival of the ancient Persian dualistic faith of Zoroastrianism and established it as the state religion, with the result that the Christians were increasingly subjected to repressive measures. Nevertheless, it was not until Christianity became the state religion in the West (380) that enmity toward Rome was focused on the Eastern Christians. After the Muslim conquest in the 7th century, the caliphate tolerated other faiths but forbade proselytism and subjected Christians to heavy taxation.

The missionary Addai evangelized Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) about the middle of the 2nd century. An ancient legend recorded by Eusebius (AD 260–340) and also found in the Doctrine of Addai (c. AD 400) (from information in the royal archives of Edessa) describes how King Abgar V of Edessa communicated to Jesus, requesting he come and heal him, to which appeal he received a reply. It is said that after the resurrection, Thomas sent Addai (or Thaddaeus), to the king, with the result that the city was won to the Christian faith. In this mission he was accompanied by a disciple, Mari, and the two are regarded as co-founders of the church, according to the Liturgy of Addai and Mari (c. AD 200), which is still the normal liturgy of the Assyrian church. The Doctrine of Addai further states that Thomas was regarded as an apostle of the church in Edessa.[143]

Addai, who became the first bishop of Edessa, was succeeded by Aggai, then by Palut, who was ordained about 200 by Serapion of Antioch. Thence came to us in the 2nd century the famous Peshitta, or Syriac translation of the Old Testament; also Tatian's Diatessaron, which was compiled about 172 and in common use until St. Rabbula, Bishop of Edessa (412–435), forbade its use. This arrangement of the four canonical gospels as a continuous narrative, whose original language may have been Syriac, Greek, or even Latin, circulated widely in Syriac-speaking Churches.[148]

A Christian council was held at Edessa as early as 197.[149] In 201 the city was devastated by a great flood, and the Christian church was destroyed.[150] In 232, the Syriac Acts were written supposedly on the event of the relics of the Apostle Thomas being handed to the church in Edessa. Under Roman domination many martyrs suffered at Edessa: Sts. Scharbîl and Barsamya, under Decius; Sts. Gûrja, Schâmôna, Habib, and others under Diocletian. In the meanwhile Christian priests from Edessa had evangelized Eastern Mesopotamia and Persia, and established the first churches in the kingdom of the Sasanians.[151] Atillâtiâ, Bishop of Edessa, assisted at the First Council of Nicaea (325).

By the latter half of the 2nd century, Christianity had spread east throughout Media, Persia, Parthia, and Bactria. The twenty bishops and many presbyters were more of the order of itinerant missionaries, passing from place to place as Paul did and supplying their needs with such occupations as merchant or craftsman. By AD 280 the metropolis of Seleucia assumed the title of "Catholicos" and in AD 424 a council of the church at Seleucia elected the first patriarch to have jurisdiction over the whole church of the East. The seat of the Patriarchate was fixed at Seleucia-Ctesiphon, since this was an important point on the east–west trade routes which extended to India and China, Java and Japan. Thus the shift of ecclesiastical authority was away from Edessa, which in AD 216 had become tributary to Rome. the establishment of an independent patriarchate with nine subordinate metropoli contributed to a more favourable attitude by the Persian government, which no longer had to fear an ecclesiastical alliance with the common enemy, Rome.

By the time that Edessa was incorporated into the Persian Empire in 258, the city of Arbela, situated on the Tigris in what is now Iraq, had taken on more and more the role that Edessa had played in the early years, as a centre from which Christianity spread to the rest of the Persian Empire.[152]

Bardaisan, writing about 196, speaks of Christians throughout Media, Parthia and Bactria (modern-day Afghanistan)[153] and, according to Tertullian (c. 160–230), there were already a number of bishoprics within the Persian Empire by 220.[152] By 315, the bishop of Seleucia–Ctesiphon had assumed the title "Catholicos".[152] By this time, neither Edessa nor Arbela was the centre of the Church of the East anymore; ecclesiastical authority had moved east to the heart of the Persian Empire.[152] The twin cities of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, well-situated on the main trade routes between East and West, became, in the words of John Stewart, "a magnificent centre for the missionary church that was entering on its great task of carrying the gospel to the far east".[154]

During the reign of Shapur II of the Sasanian Empire, he was not initially hostile to his Christian subjects, who were led by Shemon Bar Sabbae, the Patriarch of the Church of the East, however, the conversion of Constantine the Great to Christianity caused Shapur to start distrusting his Christian subjects. He started seeing them as agents of a foreign enemy. The wars between the Sasanian and Roman empires turned Shapur's mistrust into hostility. After the death of Constantine, Shapur II, who had been preparing for a war against the Romans for several years, imposed a double tax on his Christian subjects to finance the conflict. Shemon, however, refused to pay the double tax. Shapur started pressuring Shemon and his clergy to convert to Zoroastrianism, which they refused to do. It was during this period the 'cycle of the martyrs' began during which 'many thousands of Christians' were put to death. During the following years, Shemon's successors, Shahdost and Barba'shmin, were also martyred.

A near-contemporary 5th-century Christian work, the Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen, contains considerable detail on the Persian Christians martyred under Shapur II. Sozomen estimates the total number of Christians killed as follows:

The number of men and women whose names have been ascertained, and who were martyred at this period, has been computed to be upwards of sixteen thousand, while the multitude of martyrs whose names are unknown was so great that the Persians, the Syrians, and the inhabitants of Edessa, have failed in all their efforts to compute the number.

— Sozomen, in his Ecclesiastical History, Book II, Chapter XIV[155]

To understand the penetration of the Arabian Peninsula by the Christian gospel, it is helpful to distinguish between the Bedouin nomads of the interior, who were chiefly herdsmen and unreceptive to foreign control, and the inhabitants of the settled communities of the coastal areas and oases, who were either middlemen traders or farmers and were receptive to influences from abroad. Christianity apparently gained its strongest foothold in the ancient center of Semitic civilization in South-west Arabia or Yemen (sometimes known as Seba or Sheba, whose queen visited Solomon). Because of geographic proximity, acculturation with Ethiopia was always strong, and the royal family traces its ancestry to this queen.

The presence of Arabians at Pentecost and Paul's three-year sojourn in Arabia suggest a very early gospel witness. A 4th-century church history, states that the apostle Bartholomew preached in Arabia and that Himyarites were among his converts. The Al-Jubail Church in what is now Saudi Arabia was built in the 4th century. Arabia's close relations with Ethiopia give significance to the conversion of the treasurer to the queen of Ethiopia, not to mention the tradition that the Apostle Matthew was assigned to this land.[143] Eusebius says that "one Pantaneous (c. A.D. 190) was sent from Alexandria as a missionary to the nations of the East", including southwest Arabia, on his way to India.[143]

Christianity arrived early in Nubia. In the New Testament of the Christian Bible, a treasury official of "Candace, queen of the Ethiopians" returning from a trip to Jerusalem was baptised by Philip the Evangelist:

Ethiopia at that time meant any upper Nile region. Candace was the title and perhaps, name for the Meroë or Kushite queens.

In the fourth century, bishop Athanasius of Alexandria consecrated Marcus as bishop of Philae before his death in 373, showing that Christianity had permanently penetrated the region. John of Ephesus records that a Monophysite priest named Julian converted the king and his nobles of Nobatia around 545 and another kingdom of Alodia converted around 569. By the 7th century Makuria expanded becoming the dominant power in the region so strong enough to halt the southern expansion of Islam after the Arabs had taken Egypt. After several failed invasions the new rulers agreed to a treaty with Dongola allowing for peaceful coexistence and trade. This treaty held for six hundred years allowing Arab traders introducing Islam to Nubia and it gradually supplanted Christianity. The last recorded bishop was Timothy at Qasr Ibrim in 1372.

By the year 100, more than 40 Christian communities existed in cities around the Mediterranean, including two in North Africa, at Alexandria and Cyrene, and several in Italy.

The story of how this tiny community of believers spread to many cities of the Roman Empire within less than a century is indeed a remarkable chapter in the history of humanity.

Contact with Grecian life, especially at the games of the arena [which involved nudity], made this distinction obnoxious to the Hellenists, or antinationalists; and the consequence was their attempt to appear like the Greeks by epispasm ("making themselves foreskins"; I Macc. i. 15; Josephus, "Ant." xii. 5, § 1; Assumptio Mosis, viii.; I Cor. vii. 18; Tosef., Shab. xv. 9; Yeb. 72a, b; Yer. Peah i. 16b; Yeb. viii. 9a). All the more did the law-observing Jews defy the edict of Antiochus Epiphanes prohibiting circumcision (I Macc. i. 48, 60; ii. 46); and the Jewish women showed their loyalty to the Law, even at the risk of their lives, by themselves circumcising their sons.

Circumcised barbarians, along with any others who revealed the glans penis, were the butt of ribald humor. For Greek art portrays the foreskin, often drawn in meticulous detail, as an emblem of male beauty; and children with congenitally short foreskins were sometimes subjected to a treatment, known as epispasm, that was aimed at elongation.

...[the] Church founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul; as also [by pointing out] the faith preached to men, which comes down to our time by means of the successions of the bishops. ...The blessed apostles, then, having founded and built up the Church, committed into the hands of Linus the office of the episcopate.

As for Peter, we have no knowledge at all of when he came to Rome and what he did there before he was martyred. Certainly he was not the original missionary who brought Christianity to Rome (and therefore not the founder of the church of Rome in that sense). There is no serious proof that he was the bishop (or local ecclesiastical officer) of the Roman church—a claim not made till the third century. Most likely he did not spend any major time at Rome before 58 when Paul wrote to the Romans, and so it may have been only in the 60s and relatively shortly before his martyrdom that Peter came to the capital.

church of africa carthage.

there is no doubt that even before 190 A.D. Christianity had spread vigorously within Edessa and its surroundings and that (shortly after 201 or even earlier?) the royal house joined the church

We are Christians by the one name of the Messiah. As regards our customs our brethren abstain from everything that is contrary to their profession.... Parthian Christians do not take two wives.... Our Bactrian sisters do not practice promiscuity with strangers. Persians do not take their daughters to wife. Medes do not desert their dying relations or bury them alive. Christians in Edessa do not kill their wives or sisters who commit fornication but keep them apart and commit them to the judgement of God. Christians in Hatra do not stone thieves.