Экономика ( / ˌ ɛ k ə ˈ n ɒ m ɪ k s , ˌ iː k ə - / ) [1] [2] — это социальная наука , изучающая производство , распределение и потребление товаров и услуг . [3] [4]

Экономика фокусируется на поведении и взаимодействии экономических агентов и на том, как работают экономики . Микроэкономика анализирует то, что рассматривается как основные элементы в экономиках , включая отдельных агентов и рынки , их взаимодействия и результаты взаимодействий. Отдельные агенты могут включать, например, домохозяйства, фирмы, покупателей и продавцов. Макроэкономика анализирует экономики как системы, в которых взаимодействуют производство, распределение, потребление, сбережения и инвестиционные расходы , а также факторы, влияющие на них: факторы производства , такие как труд , капитал , земля и предпринимательство , инфляция , экономический рост и государственная политика , которая оказывает влияние на эти элементы . Она также стремится анализировать и описывать мировую экономику .

Другие общие различия в экономике включают различия между позитивной экономикой , описывающей «то, что есть», и нормативной экономикой , отстаивающей «то, что должно быть»; [5] между экономической теорией и прикладной экономикой ; между рациональной и поведенческой экономикой ; и между традиционной экономикой и неортодоксальной экономикой . [6]

Экономический анализ может применяться во всем обществе, включая бизнес , [7] финансы , кибербезопасность , [8] здравоохранение , [9] инженерию [10] и правительство. [11] Он также применяется к таким разнообразным предметам, как преступность, [12] образование, [13] семья, [ 14 ] феминизм , [ 15 ] право , [ 16 ] философия , [ 17 ] политика , религия , [ 18 ] социальные институты , война , [ 19 ] наука , [ 20 ] и окружающая среда . [21]

Ранний термин для этой дисциплины был «политическая экономия», но с конца 19 века ее обычно называли «экономикой». [22] Термин в конечном итоге произошел от древнегреческого οἰκονομία ( oikonomia ), что является термином для «способа (nomos) вести домашнее хозяйство (oikos)», или, другими словами, ноу-хау οἰκονομικός ( oikonomikos ), или «управляющего домашним хозяйством или усадьбой». Производные термины, такие как «экономика», поэтому часто могут означать «бережливый» или «бережливый». [23] [24] [25] [26] В более широком смысле «политическая экономия» была способом управления полисом или государством.

Существует множество современных определений экономики ; некоторые из них отражают развивающиеся взгляды на предмет или различные взгляды среди экономистов. [27] [28] Шотландский философ Адам Смит (1776) определил то, что тогда называлось политической экономией , как «исследование природы и причин богатства наций», в частности, как:

отрасль науки государственного деятеля или законодателя [имеющая двойную цель: обеспечение] обильного дохода или средств к существованию для народа... [и] обеспечение государства или содружества доходом для общественных служб. [29]

Жан-Батист Сэй (1803), отделяя предмет от его использования в государственной политике , определил его как науку о производстве, распределении и потреблении богатства . [30] С сатирической стороны, Томас Карлейль (1849) придумал « мрачную науку » как эпитет для классической экономики , в этом контексте, обычно связанную с пессимистическим анализом Мальтуса (1798). [31] Джон Стюарт Милль (1844) далее разграничил предмет:

Наука, которая прослеживает законы таких явлений общества, которые возникают из совместных действий человечества по производству богатства, в той мере, в какой эти явления не изменяются в результате преследования какой-либо другой цели. [32]

Альфред Маршалл в своем учебнике «Принципы экономики» (1890) дал определение, которое до сих пор широко цитируется и которое расширило анализ за пределы богатства и вывело его с общественного на микроэкономический уровень:

Экономика — это изучение человека в обычной деловой жизни. Она исследует, как он получает свой доход и как он его использует. Таким образом, с одной стороны, это изучение богатства, а с другой, и более важной стороны, часть изучения человека. [33]

Лайонел Роббинс (1932) разработал выводы из того, что было названо «[п]ожно, наиболее общепринятым современным определением предмета»: [28]

Экономика – это наука, изучающая человеческое поведение как взаимосвязь между целями и ограниченными средствами, имеющими альтернативное применение. [34]

Роббинс описал определение как не классификационное в «выделении определенных видов поведения», а скорее аналитическое в «фокусировании внимания на определенном аспекте поведения, форме, навязанной влиянием дефицита ». [35] Он подтвердил, что предыдущие экономисты обычно концентрировали свои исследования на анализе богатства: как богатство создается (производство), распределяется и потребляется; и как богатство может расти. [36] Но он сказал, что экономика может использоваться для изучения других вещей, таких как война, которые находятся за пределами ее обычного фокуса. Это потому, что война имеет своей целью победу (как желаемую цель ) , порождает как издержки, так и выгоды; и ресурсы (человеческие жизни и другие издержки) используются для достижения цели. Если войну невозможно выиграть или если ожидаемые издержки перевешивают выгоды, решающие субъекты (предполагая, что они рациональны) могут никогда не начать войну ( решение ), а вместо этого изучить другие альтернативы. Экономику нельзя определить как науку, изучающую богатство, войну, преступность, образование и любую другую область, к которой может быть применен экономический анализ; ее можно определить как науку, изучающую определенный общий аспект каждого из этих предметов (все они используют ограниченные ресурсы для достижения желаемой цели).

Некоторые последующие комментарии критиковали определение как слишком широкое, не ограничивающее его предмет анализом рынков. Однако с 1960-х годов такие комментарии стихли, поскольку экономическая теория максимизирующего поведения и моделирования рационального выбора расширила область предмета на области, ранее рассматривавшиеся в других областях. [37] Есть и другие критические замечания, например, о том, что дефицит не учитывает макроэкономику высокой безработицы. [38]

Гэри Беккер , участник расширения экономики в новые области, описал подход, который он предпочитал, как «объединяющий предположения о максимизации поведения, стабильных предпочтениях и рыночном равновесии , используемые неустанно и неуклонно». [39] Один из комментариев характеризует замечание как делающее экономику подходом, а не предметом, но с большой конкретикой относительно «процесса выбора и типа социального взаимодействия , которое [такой] анализ подразумевает». Тот же источник рассматривает ряд определений, включенных в принципы учебников экономики, и приходит к выводу, что отсутствие согласия не обязательно влияет на предмет, который рассматривается в текстах. Среди экономистов в целом утверждается, что конкретное представленное определение может отражать направление, в котором, по мнению автора, развивается экономика или должна развиваться. [28]

Многие экономисты, включая лауреатов Нобелевской премии Джеймса М. Бьюкенена и Рональда Коуза, отвергают методическое определение Роббинса и продолжают предпочитать определения, подобные определениям Сэя, с точки зрения предмета. [37] Ха-Джун Чанг , например, утверждал, что определение Роббинса сделало бы экономику очень своеобразной, потому что все другие науки определяют себя с точки зрения области исследования или объекта исследования, а не методологии. На биологическом факультете не говорят, что вся биология должна изучаться с помощью анализа ДНК. Люди изучают живые организмы разными способами, поэтому некоторые люди будут проводить анализ ДНК, другие могут заниматься анатомией, а третьи могут строить игровые теоретико-модели поведения животных. Но все они называются биологией, потому что все они изучают живые организмы. По словам Ха Джун Чанга, эта точка зрения, что экономику можно и нужно изучать только одним способом (например, изучая только рациональный выбор), и идя еще на один шаг дальше и по сути переопределяя экономику как теорию всего, является очень своеобразной. [40]

Вопросы, касающиеся распределения ресурсов, встречаются во всех трудах беотийского поэта Гесиода , а несколько историков-экономистов описывали самого Гесиода как «первого экономиста». [41] Однако слово Oikos , греческое слово, от которого произошло слово economy, использовалось для обозначения вопросов, касающихся управления домашним хозяйством (под которым подразумевались землевладелец, его семья и его рабы [42] ), а не для обозначения какой-то нормативной общественной системы распределения ресурсов, что является гораздо более поздним явлением. [43] [44] [45] Ксенофонт , автор Oeconomicus , по мнению филологов , является источником слова economy. [46] Йозеф Шумпетер описал схоластических писателей XVI и XVII веков, включая Томаса де Меркадо , Луиса де Молину и Хуана де Луго , как «подошедших ближе, чем любая другая группа, к тому, чтобы быть «основателями» научной экономики» в отношении денежной теории , теории процентов и теории стоимости в рамках естественно-правовой перспективы. [47]

Две группы, которые позже были названы «меркантилистами» и «физиократами», более непосредственно повлияли на последующее развитие предмета. Обе группы были связаны с ростом экономического национализма и современного капитализма в Европе. Меркантилизм был экономической доктриной, которая процветала с 16 по 18 век в плодовитой памфлетной литературе, как купцов, так и государственных деятелей. Он утверждал, что богатство нации зависит от накопления ею золота и серебра. Нации, не имеющие доступа к рудникам, могли получать золото и серебро от торговли, только продавая товары за границу и ограничивая импорт, кроме золота и серебра. Доктрина призывала к импорту дешевого сырья для использования в производстве товаров, которые можно было бы экспортировать, и к государственному регулированию, чтобы налагать защитные пошлины на иностранные промышленные товары и запрещать производство в колониях. [48]

Физиократы , группа французских мыслителей и писателей XVIII века, разработали идею экономики как кругового потока доходов и продукции. Физиократы считали, что только сельскохозяйственное производство создает явный излишек над издержками, так что сельское хозяйство является основой всего богатства. [49] Таким образом, они выступали против меркантилистской политики поощрения производства и торговли за счет сельского хозяйства, включая импортные пошлины. Физиократы выступали за замену административно затратных налоговых сборов единым налогом на доход землевладельцев. В ответ на обширные меркантилистские торговые правила физиократы выступали за политику невмешательства , [ 50] которая призывала к минимальному вмешательству правительства в экономику. [51]

Адам Смит (1723–1790) был одним из первых экономических теоретиков. [52] Смит резко критиковал меркантилистов, но описывал физиократическую систему «со всеми ее несовершенствами» как «возможно, чистейшее приближение к истине, которое когда-либо было опубликовано» по этому вопросу. [53]

Публикация « Богатства народов » Адама Смита в 1776 году была описана как «эффективное рождение экономики как отдельной дисциплины». [54] В книге земля, труд и капитал были определены как три фактора производства и основные вкладчики в богатство нации, в отличие от физиократической идеи о том, что только сельское хозяйство является производительным.

Смит обсуждает потенциальные выгоды специализации путем разделения труда , включая повышение производительности труда и выгоды от торговли , будь то между городом и деревней или между странами. [55] Его «теорема» о том, что «разделение труда ограничено масштабами рынка», была описана как «ядро теории функций фирмы и отрасли » и «фундаментальный принцип экономической организации». [56] Смиту также приписывают «самое важное содержательное положение во всей экономике» и основу теории распределения ресурсов — что в условиях конкуренции владельцы ресурсов (труда, земли и капитала) ищут наиболее выгодные способы их использования, что приводит к равной норме прибыли для всех видов использования в равновесии (с поправкой на очевидные различия, возникающие из-за таких факторов, как обучение и безработица). [57]

В аргументе, включающем «один из самых известных отрывков во всей экономике», [58] Смит представляет каждого человека как человека, пытающегося использовать любой капитал, которым он может распоряжаться, для собственной выгоды, а не выгоды общества, [a] и ради прибыли, которая необходима на определенном уровне для использования капитала в отечественной промышленности и положительно связана со стоимостью продукции. [60] В этом:

Он, как правило, действительно не намерен содействовать общественным интересам и не знает, насколько он способствует им. Предпочитая поддержку отечественной промышленности иностранной, он преследует только свою собственную безопасность; и направляя эту промышленность таким образом, чтобы ее продукция могла иметь наибольшую ценность, он преследует только свою собственную выгоду, и в этом, как и во многих других случаях, он ведом невидимой рукой к достижению цели, которая не была частью его намерения. И не всегда для общества хуже, что это не было его частью. Преследуя свои собственные интересы, он часто способствует интересам общества более эффективно, чем когда он действительно намеревается содействовать им. [61]

Преподобный Томас Роберт Мальтус (1798) использовал концепцию убывающей доходности для объяснения низкого уровня жизни. Человеческое население , утверждал он, имело тенденцию к геометрическому росту, опережая производство продуктов питания, которое увеличивалось арифметически. Сила быстро растущего населения против ограниченного количества земли означала убывающую доходность труда. Результатом, как он утверждал, была хронически низкая заработная плата, которая не позволяла уровню жизни большинства населения подняться выше прожиточного минимума. [62] [ необходим неосновной источник ] Экономист Джулиан Саймон раскритиковал выводы Мальтуса. [63]

В то время как Адам Смит подчеркивал производство и доход, Давид Рикардо (1817) сосредоточился на распределении дохода между землевладельцами, рабочими и капиталистами. Рикардо видел неотъемлемый конфликт между землевладельцами, с одной стороны, и трудом и капиталом, с другой. Он утверждал, что рост населения и капитала, давя на фиксированное предложение земли, увеличивает арендную плату и удерживает заработную плату и прибыль. Рикардо также был первым, кто сформулировал и доказал принцип сравнительного преимущества , согласно которому каждая страна должна специализироваться на производстве и экспорте товаров, поскольку она имеет более низкую относительную стоимость производства, а не полагаться только на собственное производство. [64] Это было названо «фундаментальным аналитическим объяснением» выгод от торговли . [65]

Придя к концу классической традиции, Джон Стюарт Милль (1848) разошелся с ранними классическими экономистами по вопросу о неизбежности распределения дохода, произведенного рыночной системой. Милль указал на четкое различие между двумя ролями рынка: распределением ресурсов и распределением дохода. Рынок может быть эффективным в распределении ресурсов, но не в распределении дохода, писал он, что делает необходимым вмешательство общества. [66]

Теория стоимости была важна в классической теории. Смит писал, что «реальная цена каждой вещи... это труд и хлопоты по ее приобретению». Смит утверждал, что вместе с рентой и прибылью в цену товара входят и другие издержки, помимо заработной платы. [67] Другие классические экономисты представили вариации Смита, названные « трудовой теорией стоимости ». Классическая экономика сосредоточилась на тенденции любой рыночной экономики к установлению конечного стационарного состояния, состоящего из постоянного запаса физического богатства (капитала) и постоянной численности населения .

Марксистская (позднее марксистская) экономика происходит от классической экономики и вытекает из работ Карла Маркса . Первый том главного труда Маркса, «Капитал» , был опубликован в 1867 году. Маркс сосредоточился на трудовой теории стоимости и теории прибавочной стоимости . Маркс писал, что они были механизмами, используемыми капиталом для эксплуатации труда. [68] Трудовая теория стоимости утверждала, что стоимость обмениваемого товара определяется трудом, который был затрачен на его производство, а теория прибавочной стоимости демонстрировала, как рабочие получали только часть стоимости, созданной их трудом. [69]

Марксистская экономическая теория получила дальнейшее развитие в работах Карла Каутского (1854–1938) « Экономические учения Карла Маркса» и «Классовая борьба (Эрфуртская программа)» , Рудольфа Гильфердинга (1877–1941) «Финансовый капитал» , Владимира Ленина (1870–1924) « Развитие капитализма в России» и «Империализм, как высшая стадия капитализма» и Розы Люксембург (1871–1919) « Накопление капитала» .

В начале своего существования как социальная наука экономика была определена и подробно обсуждена как изучение производства, распределения и потребления богатства Жаном-Батистом Сэем в его «Трактате о политической экономии, или Производство, распределение и потребление богатства » (1803). Эти три пункта рассматривались только в связи с увеличением или уменьшением богатства, а не в связи с процессами их реализации. [b] Определение Сэя сохранилось частично до наших дней, измененное заменой слова «товаров и услуг» на «богатство», что означает, что богатство может включать и нематериальные объекты. Сто тридцать лет спустя Лайонел Роббинс заметил, что этого определения больше не достаточно, [c] потому что многие экономисты совершали теоретические и философские набеги в другие области человеческой деятельности. В своем «Эссе о природе и значении экономической науки » он предложил определение экономики как изучения человеческого поведения, подчиненного и ограниченного дефицитом, [d] который заставляет людей выбирать, распределять дефицитные ресурсы на конкурирующие цели и экономить (стремясь к наибольшему благосостоянию, избегая при этом растраты дефицитных ресурсов). По словам Роббинса: «Экономика — это наука, которая изучает человеческое поведение как связь между целями и дефицитными средствами, которые имеют альтернативное использование». [35] Определение Роббинса в конечном итоге стало широко принятым экономистами мейнстрима и нашло свое место в современных учебниках. [70] Хотя и далеко не единодушно, большинство экономистов мейнстрима приняли бы некоторую версию определения Роббинса, хотя многие выдвинули серьезные возражения против сферы действия и метода экономики, вытекающих из этого определения. [71]

Теория, позже названная «неоклассической экономикой», сформировалась примерно в 1870—1910 годах. Термин «экономика» был популяризирован такими неоклассическими экономистами, как Альфред Маршалл и Мэри Пейли Маршалл, как краткий синоним «экономической науки» и замена более раннему термину « политическая экономия ». [25] [26] Это соответствовало влиянию на предмет математических методов, используемых в естественных науках . [72]

Неоклассическая экономика систематически интегрировала спрос и предложение как совместные детерминанты как цены, так и количества в рыночном равновесии, влияя на распределение выпуска и распределение доходов. Она отвергла трудовую теорию стоимости классической экономики в пользу теории предельной полезности стоимости со стороны спроса и более всеобъемлющей теории издержек со стороны предложения. [73] В 20 веке неоклассические теоретики отошли от более ранней идеи, которая предлагала измерять общую полезность для общества, выбрав вместо этого порядковую полезность , которая постулирует основанные на поведении отношения между индивидами. [74] [75]

В микроэкономике неоклассическая экономика представляет стимулы и издержки как играющие всепроникающую роль в формировании принятия решений . Непосредственным примером этого является потребительская теория индивидуального спроса, которая изолирует, как цены (как издержки) и доход влияют на величину спроса. [74] В макроэкономике это отражено в раннем и продолжительном неоклассическом синтезе с кейнсианской макроэкономикой. [76] [74]

Неоклассическую экономику иногда называют ортодоксальной экономикой, будь то ее критики или сторонники. Современная мейнстримная экономика строится на неоклассической экономике, но со многими уточнениями, которые либо дополняют, либо обобщают более ранний анализ, такой как эконометрика , теория игр , анализ провалов рынка и несовершенной конкуренции , а также неоклассическая модель экономического роста для анализа долгосрочных переменных, влияющих на национальный доход .

Неоклассическая экономика изучает поведение индивидов , домохозяйств и организаций (называемых экономическими субъектами, игроками или агентами), когда они управляют или используют дефицитные ресурсы, имеющие альтернативное применение, для достижения желаемых целей. Предполагается, что агенты действуют рационально, имеют в поле зрения несколько желаемых целей, ограниченные ресурсы для достижения этих целей, набор стабильных предпочтений, определенную общую руководящую цель и способность делать выбор. Существует экономическая проблема, подлежащая изучению экономической наукой, когда решение (выбор) принимается одним или несколькими игроками для достижения наилучшего возможного результата. [77]

Кейнсианская экономика происходит от Джона Мейнарда Кейнса , в частности от его книги «Общая теория занятости, процента и денег» (1936), которая положила начало современной макроэкономике как отдельному направлению. [78] Книга была сосредоточена на детерминантах национального дохода в краткосрочной перспективе, когда цены относительно негибкие. Кейнс попытался объяснить в общих теоретических деталях, почему высокая безработица на рынке труда может не быть самокорректирующейся из-за низкого « эффективного спроса » и почему даже гибкость цен и денежно-кредитная политика могут быть бесполезными. Термин «революционный» был применен к книге из-за ее влияния на экономический анализ. [79]

В течение следующих десятилетий многие экономисты следовали идеям Кейнса и расширяли его труды. Джон Хикс и Элвин Хансен разработали модель IS–LM , которая была простой формализацией некоторых идей Кейнса о краткосрочном равновесии экономики. Франко Модильяни и Джеймс Тобин разработали важные теории частного потребления и инвестиций , соответственно, двух основных компонентов совокупного спроса . Лоуренс Кляйн построил первую крупномасштабную макроэконометрическую модель , систематически применяя кейнсианское мышление к экономике США . [80]

Сразу после Второй мировой войны кейнсианство было доминирующей экономической точкой зрения среди истеблишмента США и его союзников, а марксистская экономика была доминирующей экономической точкой зрения среди номенклатуры Советского Союза и ее союзников.

Монетаризм появился в 1950-х и 1960-х годах, его интеллектуальным лидером был Милтон Фридман . Монетаристы утверждали, что денежно-кредитная политика и другие денежные шоки, представленные ростом денежной массы, были важной причиной экономических колебаний, и, следовательно, что денежно-кредитная политика была важнее фискальной политики для целей стабилизации . [81] [82] Фридман также скептически относился к способности центральных банков проводить разумную активную денежно-кредитную политику на практике, выступая вместо этого за использование простых правил, таких как устойчивый темп роста денежной массы. [83]

Монетаризм приобрел известность в 1970-х и 1980-х годах, когда несколько крупных центральных банков следовали политике, вдохновленной монетаризмом, но позже от него снова отказались, поскольку результаты оказались неудовлетворительными. [84] [85]

Более фундаментальный вызов преобладающей кейнсианской парадигме был брошен в 1970-х годах новыми классическими экономистами, такими как Роберт Лукас , Томас Сарджент и Эдвард Прескотт . Они ввели понятие рациональных ожиданий в экономике, что имело глубокие последствия для многих экономических дискуссий, среди которых были так называемая критика Лукаса и представление реальных моделей бизнес-цикла . [86]

В 1980-х годах появилась группа исследователей, которых называли новыми кейнсианскими экономистами , в том числе Джордж Акерлоф , Джанет Йеллен , Грегори Мэнкью и Оливье Бланшар . Они приняли принцип рациональных ожиданий и другие монетаристские или новые классические идеи, такие как построение на основе моделей, использующих микроосновы и оптимизацию поведения, но одновременно подчеркивали важность различных провалов рынка для функционирования экономики, как и Кейнс. [87] Не в последнюю очередь, они предложили различные причины, которые потенциально объясняли эмпирически наблюдаемые особенности жесткости цен и заработной платы , обычно считавшиеся эндогенными особенностями моделей, а не просто предполагаемыми, как в старых моделях кейнсианского стиля.

После десятилетий часто жарких дискуссий между кейнсианцами, монетаристами, новыми классическими и новыми кейнсианскими экономистами к 2000-м годам возник синтез, часто называемый новым неоклассическим синтезом . Он объединил рациональные ожидания и оптимизирующую структуру новой классической теории с новой кейнсианской ролью номинальной жесткости и других рыночных несовершенств, таких как несовершенная информация на рынках товаров, труда и кредита. Монетаристская важность денежно-кредитной политики в стабилизации [88] экономики и, в частности, в контроле инфляции была признана, как и традиционное кейнсианское утверждение о том, что фискальная политика также может играть влиятельную роль в воздействии на совокупный спрос . Методологически синтез привел к новому классу прикладных моделей, известных как динамические стохастические модели общего равновесия или модели DSGE, происходящие от моделей реальных деловых циклов, но расширенные несколькими новыми кейнсианскими и другими функциями. Эти модели оказались очень полезными и влиятельными в разработке современной денежно-кредитной политики и теперь являются стандартными рабочими лошадками в большинстве центральных банков. [89]

После финансового кризиса 2007–2008 годов макроэкономические исследования стали уделять больше внимания пониманию и интеграции финансовой системы в модели общей экономики и проливанию света на способы, которыми проблемы в финансовом секторе могут перерасти в крупные макроэкономические рецессии. В этой и других исследовательских отраслях вдохновение из поведенческой экономики стало играть более важную роль в основной экономической теории. [90] Кроме того, неоднородность среди экономических агентов, например, различия в доходах, играет все большую роль в недавних экономических исследованиях. [91]

Другие школы или направления мысли, относящиеся к определенному стилю экономики, практикуемому и распространяемому четко определенными группами академиков, которые стали известны во всем мире, включают Фрайбургскую школу , Лозаннскую школу , Стокгольмскую школу и Чикагскую школу экономики . В 1970-х и 1980-х годах основное течение экономики иногда разделялось на подход Saltwater университетов вдоль восточного и западного побережья США и подход Freshwater или Чикагской школы . [92]

В макроэкономике существуют, в общем порядке их исторического появления в литературе: классическая экономика , неоклассическая экономика , кейнсианская экономика , неоклассический синтез , монетаризм , новая классическая экономика , новая кейнсианская экономика [93] и новый неоклассический синтез . [94]

Помимо основного направления развития экономической мысли, с течением времени развивались различные альтернативные или неортодоксальные экономические теории , позиционирующие себя в противовес основной теории. [95] К ним относятся: [95]

Кроме того, альтернативные разработки включают марксистскую экономику , конституционную экономику , институциональную экономику , эволюционную экономику , теорию зависимости , структуралистскую экономику , теорию мировых систем , эконофизику , эконодинамику , феминистскую экономику и биофизическую экономику . [101]

Феминистская экономика подчеркивает роль, которую гендер играет в экономике, бросая вызов анализам, которые делают гендер невидимым или поддерживают гендерно-угнетающие экономические системы. [102] Цель состоит в том, чтобы создать экономические исследования и анализ политики, которые были бы инклюзивными и учитывали гендерные аспекты, чтобы поощрять гендерное равенство и улучшать благосостояние маргинализированных групп.

Основная экономическая теория опирается на аналитические экономические модели . При создании теорий цель состоит в том, чтобы найти предположения, которые по крайней мере столь же просты в информационных требованиях, более точны в прогнозах и более плодотворны в создании дополнительных исследований, чем предыдущие теории. [103] В то время как неоклассическая экономическая теория представляет собой как доминирующую или ортодоксальную теоретическую, так и методологическую основу , экономическая теория также может принимать форму других школ мысли , например, в неортодоксальных экономических теориях .

В микроэкономике основными концепциями являются спрос и предложение , маржинализм , теория рационального выбора , альтернативные издержки , бюджетные ограничения , полезность и теория фирмы . [104] Ранние макроэкономические модели были сосредоточены на моделировании взаимосвязей между совокупными переменными, но поскольку эти взаимосвязи со временем, по-видимому, менялись, макроэкономисты, включая новых кейнсианцев , переформулировали свои модели с помощью микрооснов , [105] в которых микроэкономические концепции играют важную роль.

Иногда экономическая гипотеза является только качественной , а не количественной . [106]

Изложения экономических рассуждений часто используют двумерные графики для иллюстрации теоретических отношений. На более высоком уровне общности математическая экономика представляет собой применение математических методов для представления теорий и анализа проблем в экономике. Трактат Пола Самуэльсона «Основы экономического анализа» (1947) иллюстрирует этот метод, особенно в отношении максимизации поведенческих отношений агентов, достигающих равновесия. Книга была сосредоточена на изучении класса утверждений, называемых операционально значимыми теоремами в экономике, которые являются теоремами , которые предположительно могут быть опровергнуты эмпирическими данными. [107]

Экономические теории часто проверяются эмпирически , в основном посредством использования эконометрики с использованием экономических данных . [108] Контролируемые эксперименты, общие для физических наук , сложны и необычны в экономике, [109] и вместо этого широкие данные изучаются путем наблюдений ; этот тип тестирования обычно считается менее строгим, чем контролируемые эксперименты, а выводы, как правило, более предварительными. Однако область экспериментальной экономики растет, и все большее использование находят естественные эксперименты .

Статистические методы, такие как регрессионный анализ, являются распространенными. Практикующие используют такие методы для оценки размера, экономической значимости и статистической значимости («силы сигнала») предполагаемых отношений и для корректировки шума от других переменных. Таким образом, гипотеза может получить признание, хотя в вероятностном, а не определенном смысле. Принятие зависит от того, выдержит ли фальсифицируемая гипотеза испытания. Использование общепринятых методов не обязательно приводит к окончательному выводу или даже консенсусу по конкретному вопросу, учитывая различные испытания, наборы данных и предшествующие убеждения.

Экспериментальная экономика способствовала использованию научно контролируемых экспериментов . Это уменьшило давно отмеченное различие экономики от естественных наук , поскольку позволяет проводить прямые проверки того, что ранее принималось за аксиомы. [110] В некоторых случаях они обнаружили, что аксиомы не совсем верны.

В поведенческой экономике психолог Дэниел Канеман получил Нобелевскую премию по экономике в 2002 году за его и Амоса Тверски эмпирическое открытие нескольких когнитивных предубеждений и эвристик . Аналогичное эмпирическое тестирование происходит в нейроэкономике . Другим примером является предположение об узко эгоистичных предпочтениях по сравнению с моделью, которая проверяет эгоистичные, альтруистические и кооперативные предпочтения. [111] Эти методы привели некоторых к утверждению, что экономика является «подлинной наукой». [112]

Микроэкономика изучает, как субъекты, формирующие рыночную структуру , взаимодействуют на рынке , создавая рыночную систему . Эти субъекты включают частных и государственных игроков с различными классификациями, обычно работающих в условиях дефицита торгуемых единиц и регулирования . Предметом торговли может быть материальный продукт, такой как яблоки, или услуга, такая как услуги по ремонту, юридические консультации или развлечения.

Существуют различные рыночные структуры. На совершенно конкурентных рынках ни один из участников не является достаточно крупным, чтобы иметь рыночную власть для установления цены однородного продукта. Другими словами, каждый участник является «ценополучателем», поскольку ни один из участников не влияет на цену продукта. В реальном мире рынки часто сталкиваются с несовершенной конкуренцией .

Формы несовершенной конкуренции включают монополию (при которой есть только один продавец товара), дуополию (при которой есть только два продавца товара), олигополию (при которой есть несколько продавцов товара), монополистическую конкуренцию (при которой есть много продавцов, производящих высокодифференцированные товары), монопсонию (при которой есть только один покупатель товара) и олигопсонию (при которой есть несколько покупателей товара). Фирмы в условиях несовершенной конкуренции имеют потенциал быть «ценообразователями», что означает, что они могут влиять на цены своей продукции.

В методе анализа частичного равновесия предполагается, что активность на анализируемом рынке не влияет на другие рынки. Этот метод агрегирует (сумму всей активности) только на одном рынке. Теория общего равновесия изучает различные рынки и их поведение. Она агрегирует (сумму всей активности) по всем рынкам. Этот метод изучает как изменения на рынках, так и их взаимодействие, приводящее к равновесию. [113]

В микроэкономике производство — это преобразование входов в выходы . Это экономический процесс, который использует входы для создания товара или услуги для обмена или прямого использования. Производство — это поток и, следовательно, скорость выпуска за период времени. Различия включают такие производственные альтернативы, как потребление (еда, стрижки и т. д.) против инвестиционных товаров (новые тракторы, здания, дороги и т. д.), общественные блага (национальная оборона, вакцинация от оспы и т. д.) или частные товары , а также «пушки» против «масла» .

Входы, используемые в процессе производства, включают такие основные факторы производства , как трудовые услуги , капитал (производимые товары длительного пользования, используемые в производстве, такие как существующий завод) и земля (включая природные ресурсы). Другие входы могут включать промежуточные товары , используемые в производстве конечных товаров, такие как сталь в новом автомобиле.

Экономическая эффективность измеряет, насколько хорошо система генерирует желаемый результат с заданным набором входов и доступной технологией . Эффективность повышается, если больше результата генерируется без изменения входов. Широко принятым общим стандартом является эффективность по Парето , которая достигается, когда никакие дальнейшие изменения не могут улучшить положение кого-то, не ухудшая положение кого-то другого.

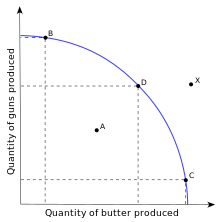

Граница производственных возможностей (PPF) — это показательная фигура для представления дефицита, стоимости и эффективности. В простейшем случае экономика может производить всего два товара (например, «ружья» и «масло»). PPF — это таблица или график (как справа), показывающие различные комбинации количеств двух товаров, которые можно произвести с заданной технологией и общими факторами производства, которые ограничивают возможный общий выпуск. Каждая точка на кривой показывает потенциальный общий выпуск для экономики, который является максимально возможным выпуском одного товара при заданном возможном количестве выпуска другого товара.

Дефицит представлен на рисунке людьми, желающими, но неспособными в совокупности потреблять сверх PPF (например, в точке X ), и отрицательным наклоном кривой. [114] Если производство одного товара увеличивается вдоль кривой, производство другого товара уменьшается , обратная зависимость . Это происходит потому, что увеличение выпуска одного товара требует переноса на него затрат из производства другого товара, уменьшая последний.

Наклон кривой в точке на ней показывает компромисс между двумя товарами. Он измеряет, сколько стоит дополнительная единица одного товара в единицах, упущенных из другого товара, пример реальной альтернативной стоимости . Таким образом, если один дополнительный Gun стоит 100 единиц масла, альтернативная стоимость одного Gun составляет 100 единиц масла. Вдоль PPF дефицит подразумевает, что выбор большего количества одного товара в совокупности влечет за собой использование меньшего количества другого товара. Тем не менее, в рыночной экономике движение вдоль кривой может указывать на то, что выбор увеличенного выпуска, как ожидается, будет стоить затрат для агентов.

By construction, each point on the curve shows productive efficiency in maximizing output for given total inputs. A point inside the curve (as at A), is feasible but represents production inefficiency (wasteful use of inputs), in that output of one or both goods could increase by moving in a northeast direction to a point on the curve. Examples cited of such inefficiency include high unemployment during a business-cycle recession or economic organisation of a country that discourages full use of resources. Being on the curve might still not fully satisfy allocative efficiency (also called Pareto efficiency) if it does not produce a mix of goods that consumers prefer over other points.

Much applied economics in public policy is concerned with determining how the efficiency of an economy can be improved. Recognizing the reality of scarcity and then figuring out how to organise society for the most efficient use of resources has been described as the "essence of economics", where the subject "makes its unique contribution."[115]

Specialisation is considered key to economic efficiency based on theoretical and empirical considerations. Different individuals or nations may have different real opportunity costs of production, say from differences in stocks of human capital per worker or capital/labour ratios. According to theory, this may give a comparative advantage in production of goods that make more intensive use of the relatively more abundant, thus relatively cheaper, input.

Even if one region has an absolute advantage as to the ratio of its outputs to inputs in every type of output, it may still specialise in the output in which it has a comparative advantage and thereby gain from trading with a region that lacks any absolute advantage but has a comparative advantage in producing something else.

It has been observed that a high volume of trade occurs among regions even with access to a similar technology and mix of factor inputs, including high-income countries. This has led to investigation of economies of scale and agglomeration to explain specialisation in similar but differentiated product lines, to the overall benefit of respective trading parties or regions.[116][117]

The general theory of specialisation applies to trade among individuals, farms, manufacturers, service providers, and economies. Among each of these production systems, there may be a corresponding division of labour with different work groups specializing, or correspondingly different types of capital equipment and differentiated land uses.[118]

An example that combines features above is a country that specialises in the production of high-tech knowledge products, as developed countries do, and trades with developing nations for goods produced in factories where labour is relatively cheap and plentiful, resulting in different in opportunity costs of production. More total output and utility thereby results from specializing in production and trading than if each country produced its own high-tech and low-tech products.

Theory and observation set out the conditions such that market prices of outputs and productive inputs select an allocation of factor inputs by comparative advantage, so that (relatively) low-cost inputs go to producing low-cost outputs. In the process, aggregate output may increase as a by-product or by design.[119] Such specialisation of production creates opportunities for gains from trade whereby resource owners benefit from trade in the sale of one type of output for other, more highly valued goods. A measure of gains from trade is the increased income levels that trade may facilitate.[120]

Prices and quantities have been described as the most directly observable attributes of goods produced and exchanged in a market economy.[121] The theory of supply and demand is an organizing principle for explaining how prices coordinate the amounts produced and consumed. In microeconomics, it applies to price and output determination for a market with perfect competition, which includes the condition of no buyers or sellers large enough to have price-setting power.

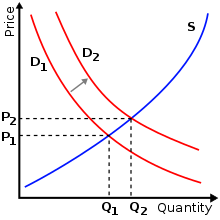

For a given market of a commodity, demand is the relation of the quantity that all buyers would be prepared to purchase at each unit price of the good. Demand is often represented by a table or a graph showing price and quantity demanded (as in the figure). Demand theory describes individual consumers as rationally choosing the most preferred quantity of each good, given income, prices, tastes, etc. A term for this is "constrained utility maximisation" (with income and wealth as the constraints on demand). Here, utility refers to the hypothesised relation of each individual consumer for ranking different commodity bundles as more or less preferred.

The law of demand states that, in general, price and quantity demanded in a given market are inversely related. That is, the higher the price of a product, the less of it people would be prepared to buy (other things unchanged). As the price of a commodity falls, consumers move toward it from relatively more expensive goods (the substitution effect). In addition, purchasing power from the price decline increases ability to buy (the income effect). Other factors can change demand; for example an increase in income will shift the demand curve for a normal good outward relative to the origin, as in the figure. All determinants are predominantly taken as constant factors of demand and supply.

Supply is the relation between the price of a good and the quantity available for sale at that price. It may be represented as a table or graph relating price and quantity supplied. Producers, for example business firms, are hypothesised to be profit maximisers, meaning that they attempt to produce and supply the amount of goods that will bring them the highest profit. Supply is typically represented as a function relating price and quantity, if other factors are unchanged.

That is, the higher the price at which the good can be sold, the more of it producers will supply, as in the figure. The higher price makes it profitable to increase production. Just as on the demand side, the position of the supply can shift, say from a change in the price of a productive input or a technical improvement. The "Law of Supply" states that, in general, a rise in price leads to an expansion in supply and a fall in price leads to a contraction in supply. Here as well, the determinants of supply, such as price of substitutes, cost of production, technology applied and various factors inputs of production are all taken to be constant for a specific time period of evaluation of supply.

Market equilibrium occurs where quantity supplied equals quantity demanded, the intersection of the supply and demand curves in the figure above. At a price below equilibrium, there is a shortage of quantity supplied compared to quantity demanded. This is posited to bid the price up. At a price above equilibrium, there is a surplus of quantity supplied compared to quantity demanded. This pushes the price down. The model of supply and demand predicts that for given supply and demand curves, price and quantity will stabilise at the price that makes quantity supplied equal to quantity demanded. Similarly, demand-and-supply theory predicts a new price-quantity combination from a shift in demand (as to the figure), or in supply.

People frequently do not trade directly on markets. Instead, on the supply side, they may work in and produce through firms. The most obvious kinds of firms are corporations, partnerships and trusts. According to Ronald Coase, people begin to organise their production in firms when the costs of doing business becomes lower than doing it on the market.[122] Firms combine labour and capital, and can achieve far greater economies of scale (when the average cost per unit declines as more units are produced) than individual market trading.

In perfectly competitive markets studied in the theory of supply and demand, there are many producers, none of which significantly influence price. Industrial organisation generalises from that special case to study the strategic behaviour of firms that do have significant control of price. It considers the structure of such markets and their interactions. Common market structures studied besides perfect competition include monopolistic competition, various forms of oligopoly, and monopoly.[123]

Managerial economics applies microeconomic analysis to specific decisions in business firms or other management units. It draws heavily from quantitative methods such as operations research and programming and from statistical methods such as regression analysis in the absence of certainty and perfect knowledge. A unifying theme is the attempt to optimise business decisions, including unit-cost minimisation and profit maximisation, given the firm's objectives and constraints imposed by technology and market conditions.[124]

Uncertainty in economics is an unknown prospect of gain or loss, whether quantifiable as risk or not. Without it, household behaviour would be unaffected by uncertain employment and income prospects, financial and capital markets would reduce to exchange of a single instrument in each market period, and there would be no communications industry.[125] Given its different forms, there are various ways of representing uncertainty and modelling economic agents' responses to it.[126]

Game theory is a branch of applied mathematics that considers strategic interactions between agents, one kind of uncertainty. It provides a mathematical foundation of industrial organisation, discussed above, to model different types of firm behaviour, for example in a solipsistic industry (few sellers), but equally applicable to wage negotiations, bargaining, contract design, and any situation where individual agents are few enough to have perceptible effects on each other. In behavioural economics, it has been used to model the strategies agents choose when interacting with others whose interests are at least partially adverse to their own.[127]

In this, it generalises maximisation approaches developed to analyse market actors such as in the supply and demand model and allows for incomplete information of actors. The field dates from the 1944 classic Theory of Games and Economic Behavior by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern. It has significant applications seemingly outside of economics in such diverse subjects as the formulation of nuclear strategies, ethics, political science, and evolutionary biology.[128]

Risk aversion may stimulate activity that in well-functioning markets smooths out risk and communicates information about risk, as in markets for insurance, commodity futures contracts, and financial instruments. Financial economics or simply finance describes the allocation of financial resources. It also analyses the pricing of financial instruments, the financial structure of companies, the efficiency and fragility of financial markets,[129] financial crises, and related government policy or regulation.[130][131][132][133][134]

Some market organisations may give rise to inefficiencies associated with uncertainty. Based on George Akerlof's "Market for Lemons" article, the paradigm example is of a dodgy second-hand car market. Customers without knowledge of whether a car is a "lemon" depress its price below what a quality second-hand car would be.[135] Information asymmetry arises here, if the seller has more relevant information than the buyer but no incentive to disclose it. Related problems in insurance are adverse selection, such that those at most risk are most likely to insure (say reckless drivers), and moral hazard, such that insurance results in riskier behaviour (say more reckless driving).[136]

Both problems may raise insurance costs and reduce efficiency by driving otherwise willing transactors from the market ("incomplete markets"). Moreover, attempting to reduce one problem, say adverse selection by mandating insurance, may add to another, say moral hazard. Information economics, which studies such problems, has relevance in subjects such as insurance, contract law, mechanism design, monetary economics, and health care.[136] Applied subjects include market and legal remedies to spread or reduce risk, such as warranties, government-mandated partial insurance, restructuring or bankruptcy law, inspection, and regulation for quality and information disclosure.[137][138][139][140][141]

The term "market failure" encompasses several problems which may undermine standard economic assumptions. Although economists categorise market failures differently, the following categories emerge in the main texts.[e]

Information asymmetries and incomplete markets may result in economic inefficiency but also a possibility of improving efficiency through market, legal, and regulatory remedies, as discussed above.

Natural monopoly, or the overlapping concepts of "practical" and "technical" monopoly, is an extreme case of failure of competition as a restraint on producers. Extreme economies of scale are one possible cause.

Public goods are goods which are under-supplied in a typical market. The defining features are that people can consume public goods without having to pay for them and that more than one person can consume the good at the same time.

Externalities occur where there are significant social costs or benefits from production or consumption that are not reflected in market prices. For example, air pollution may generate a negative externality, and education may generate a positive externality (less crime, etc.). Governments often tax and otherwise restrict the sale of goods that have negative externalities and subsidise or otherwise promote the purchase of goods that have positive externalities in an effort to correct the price distortions caused by these externalities.[142] Elementary demand-and-supply theory predicts equilibrium but not the speed of adjustment for changes of equilibrium due to a shift in demand or supply.[143]

In many areas, some form of price stickiness is postulated to account for quantities, rather than prices, adjusting in the short run to changes on the demand side or the supply side. This includes standard analysis of the business cycle in macroeconomics. Analysis often revolves around causes of such price stickiness and their implications for reaching a hypothesised long-run equilibrium. Examples of such price stickiness in particular markets include wage rates in labour markets and posted prices in markets deviating from perfect competition.

Some specialised fields of economics deal in market failure more than others. The economics of the public sector is one example. Much environmental economics concerns externalities or "public bads".

Policy options include regulations that reflect cost–benefit analysis or market solutions that change incentives, such as emission fees or redefinition of property rights.[144]

Welfare economics uses microeconomics techniques to evaluate well-being from allocation of productive factors as to desirability and economic efficiency within an economy, often relative to competitive general equilibrium.[145] It analyses social welfare, however measured, in terms of economic activities of the individuals that compose the theoretical society considered. Accordingly, individuals, with associated economic activities, are the basic units for aggregating to social welfare, whether of a group, a community, or a society, and there is no "social welfare" apart from the "welfare" associated with its individual units.

Macroeconomics, another branch of economics, examines the economy as a whole to explain broad aggregates and their interactions "top down", that is, using a simplified form of general-equilibrium theory.[146] Such aggregates include national income and output, the unemployment rate, and price inflation and subaggregates like total consumption and investment spending and their components. It also studies effects of monetary policy and fiscal policy.

Since at least the 1960s, macroeconomics has been characterised by further integration as to micro-based modelling of sectors, including rationality of players, efficient use of market information, and imperfect competition.[147] This has addressed a long-standing concern about inconsistent developments of the same subject.[148]

Macroeconomic analysis also considers factors affecting the long-term level and growth of national income. Such factors include capital accumulation, technological change and labour force growth.[149]

Growth economics studies factors that explain economic growth – the increase in output per capita of a country over a long period of time. The same factors are used to explain differences in the level of output per capita between countries, in particular why some countries grow faster than others, and whether countries converge at the same rates of growth.

Much-studied factors include the rate of investment, population growth, and technological change. These are represented in theoretical and empirical forms (as in the neoclassical and endogenous growth models) and in growth accounting.[150]

The economics of a depression were the spur for the creation of "macroeconomics" as a separate discipline. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes authored a book entitled The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money outlining the key theories of Keynesian economics. Keynes contended that aggregate demand for goods might be insufficient during economic downturns, leading to unnecessarily high unemployment and losses of potential output.

He therefore advocated active policy responses by the public sector, including monetary policy actions by the central bank and fiscal policy actions by the government to stabilise output over the business cycle.[151]Thus, a central conclusion of Keynesian economics is that, in some situations, no strong automatic mechanism moves output and employment towards full employment levels. John Hicks' IS/LM model has been the most influential interpretation of The General Theory.

Over the years, understanding of the business cycle has branched into various research programmes, mostly related to or distinct from Keynesianism. The neoclassical synthesis refers to the reconciliation of Keynesian economics with classical economics, stating that Keynesianism is correct in the short run but qualified by classical-like considerations in the intermediate and long run.[76]

New classical macroeconomics, as distinct from the Keynesian view of the business cycle, posits market clearing with imperfect information. It includes Friedman's permanent income hypothesis on consumption and "rational expectations" theory,[152] led by Robert Lucas, and real business cycle theory.[153]

In contrast, the new Keynesian approach retains the rational expectations assumption, however it assumes a variety of market failures. In particular, New Keynesians assume prices and wages are "sticky", which means they do not adjust instantaneously to changes in economic conditions.[105]

Thus, the new classicals assume that prices and wages adjust automatically to attain full employment, whereas the new Keynesians see full employment as being automatically achieved only in the long run, and hence government and central-bank policies are needed because the "long run" may be very long.

The amount of unemployment in an economy is measured by the unemployment rate, the percentage of workers without jobs in the labour force. The labour force only includes workers actively looking for jobs. People who are retired, pursuing education, or discouraged from seeking work by a lack of job prospects are excluded from the labour force. Unemployment can be generally broken down into several types that are related to different causes.[154]

Classical models of unemployment occurs when wages are too high for employers to be willing to hire more workers. Consistent with classical unemployment, frictional unemployment occurs when appropriate job vacancies exist for a worker, but the length of time needed to search for and find the job leads to a period of unemployment.[154]

Structural unemployment covers a variety of possible causes of unemployment including a mismatch between workers' skills and the skills required for open jobs.[155] Large amounts of structural unemployment can occur when an economy is transitioning industries and workers find their previous set of skills are no longer in demand. Structural unemployment is similar to frictional unemployment since both reflect the problem of matching workers with job vacancies, but structural unemployment covers the time needed to acquire new skills not just the short term search process.[156]

While some types of unemployment may occur regardless of the condition of the economy, cyclical unemployment occurs when growth stagnates. Okun's law represents the empirical relationship between unemployment and economic growth.[157] The original version of Okun's law states that a 3% increase in output would lead to a 1% decrease in unemployment.[158]

Money is a means of final payment for goods in most price system economies, and is the unit of account in which prices are typically stated. Money has general acceptability, relative consistency in value, divisibility, durability, portability, elasticity in supply, and longevity with mass public confidence. It includes currency held by the nonbank public and checkable deposits. It has been described as a social convention, like language, useful to one largely because it is useful to others. In the words of Francis Amasa Walker, a well-known 19th-century economist, "Money is what money does" ("Money is that money does" in the original).[159]

As a medium of exchange, money facilitates trade. It is essentially a measure of value and more importantly, a store of value being a basis for credit creation. Its economic function can be contrasted with barter (non-monetary exchange). Given a diverse array of produced goods and specialised producers, barter may entail a hard-to-locate double coincidence of wants as to what is exchanged, say apples and a book. Money can reduce the transaction cost of exchange because of its ready acceptability. Then it is less costly for the seller to accept money in exchange, rather than what the buyer produces.[160]

Monetary policy is the policy that central banks conduct to accomplish their broader objectives. Most central banks in developed countries follow inflation targeting,[161] whereas the main objective for many central banks in development countries is to uphold a fixed exchange rate system.[162] The primary monetary tool is normally the adjustment of interest rates,[163] either directly via administratively changing the central bank's own interest rates or indirectly via open market operations.[164] Via the monetary transmission mechanism, interest rate changes affect investment, consumption and net export, and hence aggregate demand, output and employment, and ultimately the development of wages and inflation.

Governments implement fiscal policy to influence macroeconomic conditions by adjusting spending and taxation policies to alter aggregate demand. When aggregate demand falls below the potential output of the economy, there is an output gap where some productive capacity is left unemployed. Governments increase spending and cut taxes to boost aggregate demand. Resources that have been idled can be used by the government.

For example, unemployed home builders can be hired to expand highways. Tax cuts allow consumers to increase their spending, which boosts aggregate demand. Both tax cuts and spending have multiplier effects where the initial increase in demand from the policy percolates through the economy and generates additional economic activity.

The effects of fiscal policy can be limited by crowding out. When there is no output gap, the economy is producing at full capacity and there are no excess productive resources. If the government increases spending in this situation, the government uses resources that otherwise would have been used by the private sector, so there is no increase in overall output. Some economists think that crowding out is always an issue while others do not think it is a major issue when output is depressed.

Sceptics of fiscal policy also make the argument of Ricardian equivalence. They argue that an increase in debt will have to be paid for with future tax increases, which will cause people to reduce their consumption and save money to pay for the future tax increase. Under Ricardian equivalence, any boost in demand from tax cuts will be offset by the increased saving intended to pay for future higher taxes.

Economic inequality includes income inequality, measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people receive), and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the amount of wealth people own), and other measures such as consumption, land ownership, and human capital. Inequality exists at different extents between countries or states, groups of people, and individuals.[165] There are many methods for measuring inequality,[166] the Gini coefficient being widely used for income differences among individuals. An example measure of inequality between countries is the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index, a composite index that takes inequality into account.[167] Important concepts of equality include equity, equality of outcome, and equality of opportunity.

Research has linked economic inequality to political and social instability, including revolution, democratic breakdown and civil conflict.[168][169][170][171] Research suggests that greater inequality hinders economic growth and macroeconomic stability, and that land and human capital inequality reduce growth more than inequality of income.[168][172] Inequality is at the centre stage of economic policy debate across the globe, as government tax and spending policies have significant effects on income distribution.[168] In advanced economies, taxes and transfers decrease income inequality by one-third, with most of this being achieved via public social spending (such as pensions and family benefits.)[168]

Public economics is the field of economics that deals with economic activities of a public sector, usually government. The subject addresses such matters as tax incidence (who really pays a particular tax), cost–benefit analysis of government programmes, effects on economic efficiency and income distribution of different kinds of spending and taxes, and fiscal politics. The latter, an aspect of public choice theory, models public-sector behaviour analogously to microeconomics, involving interactions of self-interested voters, politicians, and bureaucrats.[173]

Much of economics is positive, seeking to describe and predict economic phenomena. Normative economics seeks to identify what economies ought to be like.

Welfare economics is a normative branch of economics that uses microeconomic techniques to simultaneously determine the allocative efficiency within an economy and the income distribution associated with it. It attempts to measure social welfare by examining the economic activities of the individuals that comprise society.[174]

International trade studies determinants of goods-and-services flows across international boundaries. It also concerns the size and distribution of gains from trade. Policy applications include estimating the effects of changing tariff rates and trade quotas. International finance is a macroeconomic field which examines the flow of capital across international borders, and the effects of these movements on exchange rates. Increased trade in goods, services and capital between countries is a major effect of contemporary globalisation.[175]

Labour economics seeks to understand the functioning and dynamics of the markets for wage labour. Labour markets function through the interaction of workers and employers. Labour economics looks at the suppliers of labour services (workers), the demands of labour services (employers), and attempts to understand the resulting pattern of wages, employment, and income. In economics, labour is a measure of the work done by human beings. It is conventionally contrasted with such other factors of production as land and capital. There are theories which have developed a concept called human capital (referring to the skills that workers possess, not necessarily their actual work), although there are also counter posing macro-economic system theories that think human capital is a contradiction in terms.[citation needed]

Development economics examines economic aspects of the economic development process in relatively low-income countries focusing on structural change, poverty, and economic growth. Approaches in development economics frequently incorporate social and political factors.[176]

Economics is one social science among several and has fields bordering on other areas, including economic geography, economic history, public choice, energy economics, cultural economics, family economics and institutional economics.

Law and economics, or economic analysis of law, is an approach to legal theory that applies methods of economics to law. It includes the use of economic concepts to explain the effects of legal rules, to assess which legal rules are economically efficient, and to predict what the legal rules will be.[177] A seminal article by Ronald Coase published in 1961 suggested that well-defined property rights could overcome the problems of externalities.[178]

Political economy is the interdisciplinary study that combines economics, law, and political science in explaining how political institutions, the political environment, and the economic system (capitalist, socialist, mixed) influence each other. It studies questions such as how monopoly, rent-seeking behaviour, and externalities should impact government policy.[179][180] Historians have employed political economy to explore the ways in the past that persons and groups with common economic interests have used politics to effect changes beneficial to their interests.[181]

Energy economics is a broad scientific subject area which includes topics related to energy supply and energy demand. Georgescu-Roegen reintroduced the concept of entropy in relation to economics and energy from thermodynamics, as distinguished from what he viewed as the mechanistic foundation of neoclassical economics drawn from Newtonian physics. His work contributed significantly to thermoeconomics and to ecological economics. He also did foundational work which later developed into evolutionary economics.[182]

The sociological subfield of economic sociology arose, primarily through the work of Émile Durkheim, Max Weber and Georg Simmel, as an approach to analysing the effects of economic phenomena in relation to the overarching social paradigm (i.e. modernity).[183] Classic works include Max Weber's The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905) and Georg Simmel's The Philosophy of Money (1900). More recently, the works of James S. Coleman,[184] Mark Granovetter, Peter Hedstrom and Richard Swedberg have been influential in this field.

Gary Becker in 1974 presented an economic theory of social interactions, whose applications included the family, charity, merit goods and multiperson interactions, and envy and hatred.[185] He and Kevin Murphy authored a book in 2001 that analysed market behaviour in a social environment.[186]

The professionalisation of economics, reflected in the growth of graduate programmes on the subject, has been described as "the main change in economics since around 1900".[187] Most major universities and many colleges have a major, school, or department in which academic degrees are awarded in the subject, whether in the liberal arts, business, or for professional study. See Bachelor of Economics and Master of Economics.

In the private sector, professional economists are employed as consultants and in industry, including banking and finance. Economists also work for various government departments and agencies, for example, the national treasury, central bank or National Bureau of Statistics. See Economic analyst.

There are dozens of prizes awarded to economists each year for outstanding intellectual contributions to the field, the most prominent of which is the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, though it is not a Nobel Prize.

Contemporary economics uses mathematics. Economists draw on the tools of calculus, linear algebra, statistics, game theory, and computer science.[188] Professional economists are expected to be familiar with these tools, while a minority specialise in econometrics and mathematical methods.

Harriet Martineau (1802–1876) was a widely-read populariser of classical economic thought. Mary Paley Marshall (1850–1944), the first women lecturer at a British economics faculty, wrote The Economics of Industry with her husband Alfred Marshall. Joan Robinson (1903–1983) was an important post-Keynesian economist. The economic historian Anna Schwartz (1915–2012) coauthored A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 with Milton Friedman.[189] Three women have received the Nobel Prize in Economics: Elinor Ostrom (2009), Esther Duflo (2019) and Claudia Goldin (2023). Five have received the John Bates Clark Medal: Susan Athey (2007), Esther Duflo (2010), Amy Finkelstein (2012), Emi Nakamura (2019) and Melissa Dell (2020).

Women's authorship share in prominent economic journals reduced from 1940 to the 1970s, but has subsequently risen, with different patterns of gendered coauthorship.[190] Women remain globally under-represented in the profession (19% of authors in the RePEc database in 2018), with national variation.[191]

The boundaries of what constitutes economics are further blurred by the fact that economic issues are analysed not only by 'economists' but also by historians, geographers, ecologists, management scientists, and engineers.

... in economics, controlled experiments are rare and reproducible controlled experiments even more so ...