Индонезия [b] официально Республика Индонезия [c] — государство в Юго-Восточной Азии и Океании , между Индийским и Тихим океанами. Состоит из более чем 17 000 островов , включая Суматру , Яву , Сулавеси и части Борнео и Новой Гвинеи . Индонезия — крупнейшее в мире архипелагное государство и 14-я по площади страна , площадью 1 904 569 квадратных километров (735 358 квадратных миль). С населением более 280 миллионов человек Индонезия является четвертой по численности населения страной в мире и самой густонаселенной страной с мусульманским большинством . Ява, самый густонаселенный остров в мире , является домом для более чем половины населения страны.

Индонезия — президентская республика с выборным законодательным органом . Она состоит из 38 провинций , девять из которых имеют особый автономный статус . Крупнейший город страны, Джакарта , является второй по численности населения городской территорией в мире . Индонезия имеет сухопутные границы с Папуа-Новой Гвинеей , Восточным Тимором и восточной частью Малайзии , а также морские границы с Сингапуром , полуостровом Малайзия , Вьетнамом , Таиландом , Филиппинами , Австралией , Палау и Индией . Несмотря на большую численность населения и густонаселенные регионы, Индонезия имеет обширные территории дикой природы, которые поддерживают один из самых высоких в мире уровней биоразнообразия .

Индонезийский архипелаг был ценным регионом для торговли по крайней мере с седьмого века, когда королевства Шривиджая на Суматре и позднее Маджапахит на Яве вели торговлю с субъектами из материкового Китая и Индийского субконтинента . На протяжении столетий местные правители ассимилировали иностранные влияния, что привело к расцвету индуистских и буддийских королевств. Суннитские торговцы и суфийские ученые позже принесли ислам , а европейские державы боролись друг с другом за монополизацию торговли на островах специй Молуккских островов в эпоху Великих географических открытий . После трех с половиной столетий голландского колониализма Индонезия обрела независимость после Второй мировой войны . С тех пор история Индонезии была бурной, с проблемами, вызванными стихийными бедствиями, коррупцией, сепаратизмом, процессом демократизации и периодами быстрого экономического роста.

Индонезия состоит из тысяч различных коренных этнических и сотен языковых групп, из которых яванская является крупнейшей. Общая идентичность сложилась под девизом « Bhinneka Tunggal Ika » («Единство в разнообразии» буквально , «многие, но один»), определяемым национальным языком , культурным разнообразием, религиозным плюрализмом среди мусульманского населения и историей колониализма и восстания против него. Экономика Индонезии является 16-й по величине в мире по номинальному ВВП и 7-й по величине по ППС . Это третья по величине демократия в мире, региональная держава и считается средней державой в мировых делах. Страна является членом нескольких многосторонних организаций, включая Организацию Объединенных Наций, Всемирную торговую организацию , G20 и одним из основателей Движения неприсоединения , Ассоциации государств Юго-Восточной Азии , Восточноазиатского саммита , D-8 , АТЭС и Организации исламского сотрудничества .

_-_Geographicus_-_EastIndies-colton-1855.jpg/440px-1855_Colton_Map_of_the_East_Indies_(Singapore,_Thailand,_Borneo,_Malaysia)_-_Geographicus_-_EastIndies-colton-1855.jpg)

Название Индонезия происходит от греческих слов Indos ( Ἰνδός ) и nesos ( νῆσος ), что означает «индийские острова». [12] Название восходит к 19 веку, задолго до образования независимой Индонезии. В 1850 году Джордж Виндзор Эрл , английский этнолог , предложил термины Indunesians — и, по его предпочтению, Malayunesians — для жителей «Индийского архипелага или Малайского архипелага ». [13] [14] В той же публикации один из его студентов, Джеймс Ричардсон Логан , использовал Indonesia как синоним Indian Archipelago . [15] [16] Голландские ученые, пишущие в публикациях об Ост-Индии, неохотно использовали Indonesia . Они предпочитали Malay Archipelago ( голландский : Maleische Archipel ); Нидерландская Ост-Индия ( Nederlandsch Oost Indië ), в народе Индия ; Восток ( де Ост ); и Инсулинде . [17]

После 1900 года Индонезия стала более распространенной в академических кругах за пределами Нидерландов, и местные националистические группы приняли ее для политического выражения. [17] Адольф Бастиан из Берлинского университета популяризировал это название в своей книге «Indonesien oder die Inseln des Malayischen Archipels, 1884–1894» . Первым местным ученым, использовавшим это название, был Ки Хаджар Девантара , когда в 1913 году он основал пресс-бюро в Нидерландах, Indonesisch Pers-bureau . [14]

Ископаемые останки Homo erectus , широко известного как « яванский человек », свидетельствуют о том, что Индонезийский архипелаг был заселен от двух миллионов до 500 000 лет назад. [19] [20] [21] Homo sapiens достиг региона около 43 000 лет до н. э. [22] Австронезийские народы , составляющие большую часть современного населения, мигрировали в Юго-Восточную Азию с территории современного Тайваня. Они прибыли на архипелаг около 2000 лет до н. э. и ограничили местных меланезийцев дальневосточными регионами по мере своего распространения на восток. [23]

Идеальные условия для ведения сельского хозяйства и освоение выращивания риса на влажных полях еще в восьмом веке до нашей эры [24] позволили деревням, городам и небольшим королевствам процветать к первому веку нашей эры. Стратегическое положение архипелага на морских путях способствовало межостровной и международной торговле, в том числе с индийскими королевствами и китайскими династиями, начиная с нескольких веков до нашей эры. [25] С тех пор торговля в корне сформировала историю Индонезии. [26] [27]

С седьмого века н. э. военно-морское королевство Шривиджая процветало благодаря торговле и влиянию индуизма и буддизма . [28] [29] Между восьмым и десятым веками н. э. земледельческие буддийские династии Саилендры и индуистские Матарам процветали и приходили в упадок во внутренней части острова Ява, оставив после себя величественные религиозные памятники, такие как Боробудур Саилендры и Прамбанан Матарама . Индуистское королевство Маджапахит было основано на восточной Яве в конце 13 века, и при Гадже Маде его влияние распространялось на большую часть современной Индонезии. Этот период часто называют «Золотым веком» в истории Индонезии. [30]

Самые ранние свидетельства исламизированного населения на архипелаге датируются 13-м веком в северной части Суматры . [31] Другие части архипелага постепенно приняли ислам, и он стал доминирующей религией на Яве и Суматре к концу 16-го века. По большей части ислам наложился и смешался с существующими культурными и религиозными влияниями, которые сформировали преобладающую форму ислама в Индонезии, особенно на Яве. [32]

Первые европейцы прибыли на архипелаг в 1512 году, когда португальские торговцы во главе с Франсишку Серраном стремились монополизировать источники мускатного ореха , гвоздики и перца кубеба на Молуккских островах . [33] За ними последовали голландские и британские торговцы. В 1602 году голландцы основали Голландскую Ост-Индскую компанию ( Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie ; VOC) и стали доминирующей европейской державой на протяжении почти 200 лет. VOC была распущена в 1799 году после банкротства, и Нидерланды создали Голландскую Ост-Индию как национализированную колонию. [34]

На протяжении большей части колониального периода голландский контроль над архипелагом был незначительным. Голландские войска постоянно подавляли восстания на Яве и за ее пределами. Влияние местных лидеров, таких как принц Дипонегоро в центральной Яве, имам Бонджол в центральной Суматре, Паттимура в Малуку , и кровавая тридцатилетняя война в Ачехе ослабили голландцев и связали колониальные военные силы. [35] [36] [37] Только в начале 20-го века голландское господство распространилось на то, что стало нынешними границами Индонезии. [37] [38] [39] [40]

Во время Второй мировой войны японское вторжение и оккупация положили конец голландскому правлению [41] [42] [43] и поощрили движение за независимость. [44] Через два дня после капитуляции Японии в августе 1945 года влиятельные националистические лидеры Сукарно и Мохаммад Хатта издали Прокламацию независимости Индонезии . Сукарно, Хатта и Сутан Сджахрир были назначены президентом, вице-президентом и премьер-министром соответственно. [45] [46] [47] [45] Нидерланды попытались восстановить свою власть, начав Индонезийскую национальную революцию , которая закончилась в декабре 1949 года, когда голландцы признали независимость Индонезии перед лицом международного давления. [48] [47] Несмотря на чрезвычайные политические, социальные и религиозные разногласия, индонезийцы в целом нашли единство в своей борьбе за независимость. [49] [50]

Будучи президентом, Сукарно перевел Индонезию от демократии к авторитаризму и сохранил власть, уравновешивая противоборствующие силы военных , политического ислама и все более могущественной Коммунистической партии Индонезии (КПИ). [51] Напряженность между военными и КПИ достигла кульминации в попытке государственного переворота в 1965 году. Армия под руководством генерал-майора Сухарто ответила на это спровоцированной ею жестокой антикоммунистической чисткой , в результате которой погибло от 500 000 до одного миллиона человек и еще около миллиона было заключено в концентрационные лагеря . [52] [53] [54] [55] КПИ была обвинена в перевороте и фактически уничтожена. [56] [57] [58] Сухарто воспользовался ослаблением позиций Сукарно, и после затянувшейся борьбы за власть с Сукарно , Сухарто был назначен президентом в марте 1968 года. Его поддерживаемая США администрация «Нового порядка» [59] [60] [61] [62] поощряла прямые иностранные инвестиции , [63] [64] [65] что стало решающим фактором в последующих трех десятилетиях существенного экономического роста.

Индонезия была страной, наиболее пострадавшей от азиатского финансового кризиса 1997 года . [66] Он вызвал народное недовольство коррупцией Нового порядка и подавлением политической оппозиции и в конечном итоге положил конец президентству Сухарто. [41] [67] [68] [69] В 1999 году Восточный Тимор отделился от Индонезии после вторжения Индонезии в 1975 году [70] и 25-летней оккупации, отмеченной международным осуждением нарушений прав человека . [71] С 1998 года демократические процессы были укреплены путем усиления региональной автономии и проведения первых прямых президентских выборов в стране в 2004 году . [72] Политическая, экономическая и социальная нестабильность, коррупция и случаи терроризма оставались проблемами в 2000-х годах; однако с 2007 года экономика демонстрировала высокие показатели. Хотя отношения между разнородным населением в основном гармоничны, острое религиозное недовольство и насилие остаются проблемой в некоторых областях. [73] Политическое урегулирование вооруженного сепаратистского конфликта в Ачехе было достигнуто в 2005 году. [74]

Индонезия — самая южная страна Азии. Страна расположена между 11° южной широты и 6° северной долготы и 95° восточной долготы и 141° восточной долготы . Трансконтинентальная страна, охватывающая Юго-Восточную Азию и Океанию, является крупнейшим в мире архипелагом , простирающимся на 5120 километров (3181 миль) с востока на запад и на 1760 километров (1094 миль) с севера на юг. [75] Координационное министерство страны по морским делам и инвестициям утверждает, что Индонезия имеет 17 504 острова (из которых 16 056 зарегистрированы в ООН) [76], разбросанных по обе стороны экватора, около 6000 из которых обитаемы. [77] Крупнейшими являются Суматра , Ява , Борнео (совместно с Брунеем и Малайзией), Сулавеси и Новая Гвинея (совместно с Папуа-Новой Гвинеей). [78] Индонезия имеет сухопутные границы с Малайзией на островах Борнео и Себатик , с Папуа-Новой Гвинеей на острове Новая Гвинея, с Восточным Тимором на острове Тимор и морские границы с Сингапуром, Малайзией, Вьетнамом, Филиппинами, Палау и Австралией.

С высотой 4884 метра (16024 фута) Пунчак-Джая является самой высокой вершиной Индонезии, а озеро Тоба на Суматре является крупнейшим озером, площадью 1145 км 2 (442 кв. миль). Крупнейшие реки Индонезии находятся на Калимантане и в Новой Гвинее и включают Капуас , Барито , Мамберамо , Сепик и Махакам . Они служат коммуникационными и транспортными связями между речными поселениями острова. [79]

Индонезия расположена вдоль экватора, и ее климат, как правило, относительно ровный круглый год. [80] В Индонезии два сезона — сухой и влажный — без экстремальных летних и зимних зон. [81] Для большей части Индонезии сухой сезон приходится на период с мая по октябрь, а влажный — на период с ноября по апрель. [81] Климат Индонезии почти полностью тропический , с преобладанием тропического климата дождевых лесов, который можно встретить на каждом крупном острове Индонезии. Более прохладные типы климата существуют в горных районах, которые находятся на высоте от 1300 до 1500 метров (от 4300 до 4900 футов) над уровнем моря. Океанический климат (Кеппен Cfb ) преобладает в высокогорных районах, прилегающих к климату дождевых лесов, с равномерным выпадением осадков круглый год. В высокогорных районах, близких к тропическому муссонному и тропическому климату саванны , субтропический высокогорный климат (Кеппен Cwb ) более выражен в сухой сезон. [82]

В некоторых регионах, таких как Калимантан и Суматра , наблюдаются лишь незначительные различия в количестве осадков и температуре между сезонами, тогда как в других, таких как Нуса-Тенгара, наблюдаются гораздо более выраженные различия с засухами в сухой сезон и наводнениями во влажный сезон. Количество осадков различается в зависимости от региона, больше на западе Суматры, Яве и во внутренних районах Калимантана и Папуа и меньше в районах, близких к Австралии, таких как Нуса-Тенгара, которые, как правило, относительно сухие. Почти равномерно теплые воды, составляющие 81% площади Индонезии, гарантируют, что температура на суше остается относительно постоянной. Влажность довольно высокая, от 70 до 90%. Ветры умеренные и в целом предсказуемые, муссоны обычно дуют с юга и востока с мая по октябрь и с севера и запада с ноября по апрель. Тайфуны и крупномасштабные штормы не представляют большой опасности для мореплавателей; значительную опасность представляют быстрые течения в каналах, таких как проливы Ломбок и Сапе . [84]

В нескольких исследованиях рассматривается, что Индонезия находится под серьезным риском прогнозируемых последствий изменения климата . [85] К ним относятся несокращённые выбросы, приводящие к повышению средней температуры примерно на 1 °C (2 °F) к середине столетия, [86] [87] увеличение частоты засух и нехватки продовольствия (что влияет на осадки и режимы влажных и сухих сезонов, и, таким образом, на сельскохозяйственную систему Индонезии [87] ), а также многочисленные заболевания и лесные пожары. [87] Повышение уровня моря также будет угрожать большей части населения Индонезии, которое проживает в низменных прибрежных районах. [87] [88] [89] Бедные общины, вероятно, больше всего пострадают от изменения климата. [90]

Тектонически большая часть территории Индонезии крайне нестабильна, что делает ее местом многочисленных вулканов и частых землетрясений. [91] Она расположена на Тихоокеанском огненном кольце , где Индо-Австралийская плита и Тихоокеанская плита заталкиваются под Евразийскую плиту , где они тают на глубине около 100 километров (62 мили). Цепочка вулканов проходит через Суматру, Яву , Бали и Нуса-Тенгара , а затем к островам Банда в Малуку и северо-восточному Сулавеси . [92] Из 400 вулканов около 130 являются активными. [91] В период с 1972 по 1991 год произошло 29 извержений вулканов, в основном на Яве. [93] Вулканический пепел сделал сельскохозяйственные условия непредсказуемыми в некоторых районах. [94] Однако он также привел к образованию плодородных почв, что является фактором, исторически поддерживающим высокую плотность населения Явы и Бали. [95]

Огромный супервулкан извергся на месте современного озера Тоба около 70 000 лет до н. э. Считается, что он вызвал глобальную вулканическую зиму и похолодание климата, а затем привел к генетическому узкому месту в эволюции человека, хотя это все еще обсуждается. [96] Извержение горы Тамбора в 1815 году и извержение Кракатау в 1883 году были одними из крупнейших в зарегистрированной истории. Первое вызвало 92 000 смертей и создало зонтик из вулканического пепла, который распространился и накрыл части архипелага и сделал большую часть Северного полушария без лета в 1816 году . [97] Последнее произвело самый громкий звук в зарегистрированной истории и вызвало 36 000 смертей из-за самого извержения и вызванных им цунами, со значительными дополнительными эффектами по всему миру спустя годы после события. [98] К недавним катастрофическим бедствиям, вызванным сейсмической активностью, относятся землетрясение в Индийском океане 2004 года и землетрясение в Джокьякарте 2006 года .

Размер Индонезии, тропический климат и архипелажные география поддерживают один из самых высоких уровней биоразнообразия в мире , и она входит в число 17 стран с самым большим разнообразием, определенных Conservation International . Ее флора и фауна представляют собой смесь азиатских и австралазийских видов. [99] [100] Острова Зондского шельфа (Суматра, Ява, Борнео и Бали) когда-то были связаны с материковой Азией и имеют богатую азиатскую фауну. Крупные виды, такие как суматранский тигр , носорог, орангутан, азиатский слон и леопард, когда-то были в изобилии вплоть до Бали на востоке, но численность и распространение резко сократились. Будучи долго отделенными от континентальных массивов суши, Сулавеси, Нуса-Тенгара и Малуку развили свою уникальную флору и фауну. [101] [102] Папуа была частью австралийского континента и является домом для уникальной фауны и флоры, тесно связанной с австралийской, включая более 600 видов птиц. [103]

Индонезия уступает только Австралии по общему количеству эндемичных видов, причем 36% из 1531 видов птиц и 39% из 515 видов млекопитающих являются эндемиками. [104] Индонезия занимает 83% старых лесов Юго-Восточной Азии и является местом с самым высоким содержанием лесного углерода в регионе. [105] Тропические моря окружают 80 000 километров (50 000 миль) береговой линии Индонезии. В стране есть целый ряд морских и прибрежных экосистем, включая пляжи , дюны, эстуарии, мангровые заросли, коралловые рифы, водорослевые заросли, прибрежные илистые отмели, приливные отмели, водорослевые заросли и небольшие островные экосистемы. [12] Индонезия является одной из стран Кораллового треугольника с самым большим в мире разнообразием рыб коралловых рифов , более 1650 видов только в восточной Индонезии. [106]

Британский натуралист Альфред Рассел Уоллес описал разделительную линию ( линию Уоллеса ) между распространением азиатских и австралазийских видов Индонезии. [107] Она проходит примерно с севера на юг вдоль края Зондского шельфа, между Калимантаном и Сулавеси, и вдоль глубокого пролива Ломбок , между Ломбоком и Бали. Флора и фауна на западе линии в основном азиатские, в то время как к востоку от Ломбока все больше австралийские до точки перелома на линии Вебера . В своей книге 1869 года «Малайский архипелаг » Уоллес описал многочисленные виды, уникальные для этой области. [108] Регион островов между его линией и Новой Гвинеей теперь называется Уоллесия . [107]

Большое и растущее население Индонезии и быстрая индустриализация представляют собой серьезные экологические проблемы . Им часто уделяется меньше внимания из-за высокого уровня бедности и слабого, недостаточного управления. [109] Проблемы включают уничтожение торфяников, крупномасштабную незаконную вырубку лесов (вызывающую обширную дымку в частях Юго-Восточной Азии ), чрезмерную эксплуатацию морских ресурсов, загрязнение воздуха, управление мусором и надежные услуги водоснабжения и сточных вод . [109] Эти проблемы способствуют низкому рейтингу Индонезии (номер 116 из 180 стран) в Индексе экологической эффективности 2020 года . В отчете также указывается, что показатели Индонезии в целом ниже среднего как в региональном, так и в глобальном контексте. [110]

Индонезия имеет один из самых высоких в мире темпов вырубки лесов. [111] [112] В 2020 году леса покрывали приблизительно 49,1% территории страны, [113] по сравнению с 87% в 1950 году. [114] С 1970-х годов за большую часть вырубки лесов в Индонезии отвечали лесозаготовки, различные плантации и сельское хозяйство . [114] Совсем недавно это было обусловлено индустрией пальмового масла , [115] которая подвергалась критике за ее воздействие на окружающую среду и перемещение местных общин. [112] [116] Такая ситуация сделала Индонезию крупнейшим в мире источником выбросов парниковых газов, связанных с лесами. [117] Это также угрожает выживанию местных и эндемичных видов. Международный союз охраны природы (МСОП) определил 140 видов млекопитающих как находящиеся под угрозой исчезновения и 15 как находящиеся в критическом состоянии, включая балийскую майну , [118] суматранского орангутана , [119] и яванского носорога . [120] Некоторые ученые описывают вырубку лесов и другие разрушения окружающей среды в стране как экоцид . [121] [122] [123]

Индонезия — республика с президентской системой. После падения Нового порядка в 1998 году политические и правительственные структуры претерпели масштабные реформы, в ходе которых были внесены четыре поправки в конституцию , реорганизовавшие исполнительную, законодательную и судебную ветви власти. [124] Главной из них является делегирование власти и полномочий различным региональным образованиям при сохранении унитарного государства . [125] Президент Индонезии является главой государства и главой правительства , главнокомандующим Национальными вооруженными силами Индонезии ( Tentara Nasional Indonesia , TNI) и директором по внутреннему управлению, разработке политики и иностранным делам. Президент может занимать свой пост максимум два последовательных пятилетних срока. [126]

Высшим представительным органом на национальном уровне является Народное консультативное собрание ( Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat , MPR). Его основными функциями являются поддержка и внесение поправок в конституцию, инаугурация и отстранение президента [127] [128] и формализация общих контуров государственной политики. MPR состоит из двух палат: Народного представительного совета ( Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat , DPR) с 575 членами и Регионального представительного совета ( Dewan Perwakilan Daerah , DPD) с 136 членами [129]. DPR принимает законы и контролирует исполнительную власть. Реформы с 1998 года заметно увеличили его роль в национальном управлении [124], в то время как DPD является новой палатой для вопросов регионального управления [130] [128]

Большинство гражданских споров рассматриваются в Государственном суде ( Pengadilan Negeri ); апелляции рассматриваются в Высоком суде ( Pengadilan Tinggi ). Верховный суд Индонезии ( Mahkamah Agung ) является высшим уровнем судебной власти и рассматривает окончательные апелляции о прекращении и проводит пересмотры дел. Другие суды включают Конституционный суд ( Mahkamah Konstitusi ), который рассматривает конституционные и политические вопросы, и Религиозный суд ( Pengadilan Agama ), который занимается делами по кодифицированному исламскому личному праву ( шариату ). [131] Кроме того, Судебная комиссия ( Komisi Yudisial ) контролирует работу судей. [132]

С 1999 года в Индонезии действует многопартийная система. На всех выборах в законодательные органы с момента падения Нового порядка ни одна политическая партия не получила абсолютного большинства мест. Индонезийская демократическая партия борьбы (PDI-P), которая получила наибольшее количество голосов на выборах 2019 года , является партией действующего президента Джоко Видодо . [133] Другие известные партии включают Партию функциональных групп ( Golkar ), Партию великого движения Индонезии ( Gerindra ), Демократическую партию и Партию процветающей справедливости (PKS).

Первые всеобщие выборы были проведены в 1955 году для избрания членов DPR и Конституционной ассамблеи ( Konstituante ). Последние выборы в 2019 году привели к появлению девяти политических партий в DPR с парламентским порогом в 4% от числа голосов избирателей страны. [134] На национальном уровне индонезийцы не выбирали президента до 2004 года. С тех пор президент избирается на пятилетний срок, как и партийные члены DPR и беспартийной DPD. [129] [124] Начиная с местных выборов 2015 года , выборы губернаторов и мэров проводились в один и тот же день. В 2014 году Конституционный суд постановил, что законодательные и президентские выборы будут проводиться одновременно, начиная с 2019 года. [135]

Индонезия имеет несколько уровней подразделений. Первый уровень — провинции , в которых есть законодательный орган ( Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah , DPRD) и избираемый губернатор . Всего было создано 38 провинций из первоначальных восьми в 1945 году, [136] последним изменением стало отделение Юго-Западного Папуа от провинции Западное Папуа в 2022 году. [137] Второй уровень — регентства ( kabupaten ) и города ( kota ), возглавляемые регентами ( bupati ) и мэрами ( walikota ) соответственно, а также законодательный орган ( DPRD Kabupaten/Kota ). Третий уровень — это районы ( кечаматан , дистрик в Папуа , или капаневон и кемантрен в Джокьякарте ), а четвёртый — деревни (либо деса , келурахан , кампунг , нагари на Западной Суматре , либо гампонг в Ачехе ). [138]

Деревня является самым низким уровнем государственного управления. Она делится на несколько общественных групп ( rukun warga , RW), которые в свою очередь делятся на соседские группы ( rukun tetangga , RT). На Яве деревня ( desa ) делится на более мелкие единицы, называемые dusun или dukuh (деревни), которые являются тем же самым, что и RW. После внедрения мер региональной автономии в 2001 году, округа и города стали главными административными единицами, ответственными за предоставление большинства государственных услуг. Уровень администрации деревни является наиболее влиятельным в повседневной жизни гражданина и решает вопросы деревни или района через избранного главу деревни ( lurah или kepala desa ). [139]

Девять провинций — Ачех, Джакарта, Джокьякарта, Папуа , Центральное Папуа , Высокогорное Папуа , Южное Папуа , Юго-Западное Папуа и Западное Папуа — получили от центрального правительства особый автономный статус ( otonomi khusus ). Ачех, консервативная исламская территория , имеет право создавать некоторые аспекты независимой правовой системы, реализующей шариат . [140] Джокьякарта — единственная доколониальная монархия, юридически признанная в Индонезии, при этом должности губернатора и вице-губернатора являются приоритетными для правящего султана Джокьякарты и герцога Пакуаламана соответственно. [141] Шесть папуасских провинций — единственные, где коренные народы имеют привилегии в своем местном самоуправлении. [142]

Индонезия имеет 132 дипломатических миссии за рубежом, включая 95 посольств. [144] Страна придерживается того, что она называет «свободной и активной» внешней политикой, стремясь играть роль в региональных делах пропорционально своему размеру и местоположению, но избегая участия в конфликтах между другими странами. [145]

Индонезия была значительным полем битвы во время Холодной войны. Многочисленные попытки Соединенных Штатов и Советского Союза , [146] [147] и Китая в некоторой степени, [148] достигли кульминации в попытке переворота 1965 года и последовавших потрясений, которые привели к переориентации внешней политики. [149] Тихое выравнивание с западным миром при сохранении неприсоединившейся позиции характеризовало внешнюю политику Индонезии с тех пор. [150] Сегодня она поддерживает тесные отношения со своими соседями и является одним из основателей Ассоциации государств Юго-Восточной Азии ( АСЕАН ) и Восточноазиатского саммита . Как и большинство стран мусульманского мира , Индонезия не имеет дипломатических отношений с Израилем и активно поддерживает Палестину . Однако наблюдатели отмечают, что у Индонезии есть связи с Израилем, хотя и скрытные. [151]

Индонезия является членом Организации Объединенных Наций с 1950 года [d] и была одним из основателей Движения неприсоединения (ДН) и Организации исламского сотрудничества (ОИС). [153] Индонезия является участником Соглашения о зоне свободной торговли АСЕАН , Кернской группы , Всемирной торговой организации (ВТО) и бывшим членом ОПЕК . [154] Индонезия является получателем гуманитарной и развивающей помощи с 1967 года, [155] [156] и недавно, в конце 2019 года, страна учредила свою первую программу зарубежной помощи. [157]

Вооруженные силы Индонезии (TNI) включают армию (TNI–AD), военно-морской флот (TNI–AL, включая корпус морской пехоты ) и военно-воздушные силы (TNI–AU). В армии насчитывается около 400 000 действующих военнослужащих. Расходы на оборону в национальном бюджете составили 0,7% от валового внутреннего продукта (ВВП) в 2018 году [158] с противоречивым участием военных коммерческих интересов и фондов. [159] Вооруженные силы были сформированы во время Индонезийской национальной революции , когда они вели партизанскую войну вместе с неформальным ополчением. С тех пор территориальные линии легли в основу структуры всех отделений TNI, направленных на поддержание внутренней стабильности и сдерживание внешних угроз. [160] Военные обладали сильным политическим влиянием с момента своего основания, которое достигло пика во время Нового порядка . Политические реформы 1998 года включали исключение формального представительства TNI из законодательного органа. Тем не менее, их политическое влияние сохраняется, хотя и на более низком уровне. [161]

После обретения независимости страна боролась за сохранение единства в борьбе с местными мятежами и сепаратистскими движениями. [162] Некоторые из них, особенно в Ачехе и Папуа , привели к вооруженному конфликту и последующим обвинениям в нарушениях прав человека и жестокости со всех сторон. [163] [164] [165] Первый конфликт был урегулирован мирным путем в 2005 году, [74] в то время как второй продолжался на фоне значительного, хотя и несовершенного, осуществления законов региональной автономии и зарегистрированного снижения уровня насилия и нарушений прав человека по состоянию на 2006 год. [166] Другие действия армии включают конфликт против Нидерландов из-за голландской Новой Гвинеи , оппозицию спонсируемому британцами созданию Малайзии (« Конфронтаси »), массовые убийства Индонезийской коммунистической партии (КПИ) и вторжение в Восточный Тимор , которое остается самой масштабной военной операцией Индонезии. [167] [168]

Indonesia has a mixed economy in which the private sector and government play vital roles.[170] As the only G20 member state in Southeast Asia,[171] the country has the largest economy in the region and is classified as a newly industrialised country. Per a 2023 estimate, it is the world's 16th largest economy by nominal GDP and 7th in terms of GDP at PPP, estimated to be US$1.417 trillion and US$4.393 trillion, respectively. Per capita GDP in PPP is US$15,835, while nominal per capita GDP is US$5,108.[7] Services are the economy's largest sector and account for 43.4% of GDP (2018), followed by industry (39.7%) and agriculture (12.8%).[172] Since 2009, it has employed more people than other sectors, accounting for 47.7% of the total labour force, followed by agriculture (30.2%) and industry (21.9%).[173]

Over time, the structure of the economy has changed considerably.[174] Historically, it has been weighted heavily towards agriculture, reflecting both its stage of economic development and government policies in the 1950s and 1960s to promote agricultural self-sufficiency.[174] A gradual process of industrialisation and urbanisation began in the late 1960s and accelerated in the 1980s as falling oil prices saw the government focus on diversifying away from oil exports and towards manufactured exports.[174] This development continued throughout the 1980s and into the next decade despite the 1990 oil price shock, during which the GDP rose at an average rate of 7.1%. As a result, the official poverty rate fell from 60% to 15%.[175] Trade barriers reduction from the mid-1980s made the economy more globally integrated. The growth ended with the 1997 Asian financial crisis that severely impacted the economy, including a 13.1% real GDP contraction in 1998 and a 78% inflation. The economy reached its low point in mid-1999 with only 0.8% real GDP growth.[176]

Relatively steady inflation[177] and an increase in GDP deflator and the Consumer Price Index[178] have contributed to strong economic growth in recent years. From 2007 to 2019, annual growth accelerated to between 4% and 6% due to improvements in the banking sector and domestic consumption,[179] helping Indonesia weather the 2008–2009 Great Recession,[180] and regain in 2011 the investment grade rating it had lost in 1997.[181] As of 2019[update], 9.41% of the population lived below the poverty line, and the official open unemployment rate was 5.28%.[182] During the first year of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the economy suffered its first recession since the 1997 crisis but recovered in the following year.[183]

Indonesia has abundant natural resources. Its primary industries are fishing, petroleum, timber, paper products, cotton cloth, tourism, petroleum mining, natural gas, bauxite, coal and tin. Its main agricultural products are rice, coconuts, soybeans, bananas, coffee, tea, palm, rubber, and sugar cane.[184] Indonesia is the world's largest producer of nickel.[185] These commodities make up a large portion of the country's exports, with palm oil and coal briquettes as the leading export commodities. In addition to refined and crude petroleum as the primary imports, telephones, vehicle parts and wheat cover the majority of additional imports. China, the United States, Japan, Singapore, India, Malaysia, South Korea and Thailand are Indonesia's principal export markets and import partners.[186]

Tourism contributed around US$9.8 billion to GDP in 2020, and in the previous year, Indonesia received 15.4 million visitors.[188] Overall, Australia, China, Singapore, Malaysia, and Japan are the top five sources of visitors to Indonesia.[189] Since 2011, Wonderful Indonesia has been the country's international marketing campaign slogan to promote tourism.[190]

Nature and culture are prime attractions of Indonesian tourism. The country has a well-preserved natural ecosystem with rainforests stretching over about 57% of Indonesia's land (225 million acres). Forests on Sumatra and Kalimantan are examples of popular destinations, such as the Orangutan wildlife reserve. Moreover, Indonesia has one of the world's longest coastlines, measuring 54,716 kilometres (33,999 mi). The ancient Borobudur and Prambanan temples, as well as Toraja and Bali with their traditional festivities, are some of the popular destinations for cultural tourism.[192]

Indonesia has ten UNESCO World Heritage Sites, including the Komodo National Park and the Cosmological Axis of Yogyakarta and its Historic Landmarks; and a further 18 in a tentative list that includes Bunaken National Park and Raja Ampat Islands.[193] Other attractions include specific points in Indonesian history, such as the colonial heritage of the Dutch East Indies in the old towns of Jakarta and Semarang and the royal palaces of Pagaruyung and Ubud.[192]

Government expenditure on research and development is relatively low (0.3% of GDP in 2019),[194] and Indonesia only ranked 61st on the 2023 Global Innovation Index report.[195] Historical examples of scientific and technological developments include the paddy cultivation technique terasering, which is common in Southeast Asia, and the pinisi boats by the Bugis and Makassar people.[196] In the 1980s, Indonesian engineer Tjokorda Raka Sukawati invented a road construction technique named Sosrobahu that later became widely used in several countries.[197] The country is also an active producer of passenger trains and freight wagons with its state-owned company, the Indonesian Railway Industry (INKA), and has exported trains abroad.[198]

Indonesia has a long history of developing military and small commuter aircraft. It is the only country in Southeast Asia to build and produce aircraft. The state-owned Indonesian Aerospace company (PT. Dirgantara Indonesia) has provided components for Boeing and Airbus.[199] The company also collaborated with EADS CASA of Spain to develop the CN-235, which has been used by several countries.[200] Former President B. J. Habibie played a vital role in this achievement.[201] Indonesia has also joined the South Korean programme to manufacture the 4.5-generation fighter jet KAI KF-21 Boramae.[202]

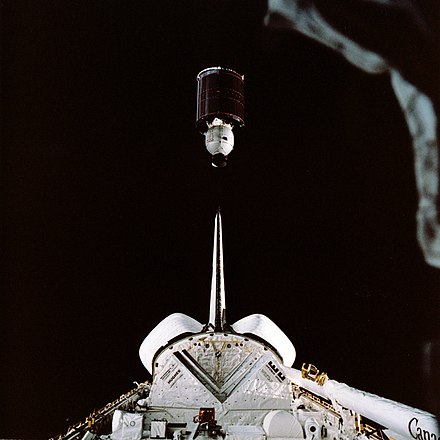

Indonesia has a space programme and space agency, the National Institute of Aeronautics and Space (Lembaga Penerbangan dan Antariksa Nasional, LAPAN). In the 1970s, Indonesia became the first developing country to operate a satellite system called Palapa,[203] a series of communication satellites owned by Indosat. The first satellite, PALAPA A1, was launched on 8 July 1976 from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, United States.[204] As of 2024[update], Indonesia has launched 19 satellites for various purposes.[205]

In May 2024, Indonesia granted licensure to satellite internet provider Starlink aimed at bringing Internet connectivity to the rural and underserved regions of Indonesia.[206]

Indonesia's transport system has been shaped over time by the economic resource base of an archipelago and the distribution of its 275 million people highly concentrated on Java.[207] All transport modes play a role in the country's transport system and are generally complementary rather than competitive. In 2016, the transport sector generated about 5.2% of GDP.[208]

The road transport system is predominant, with a total length of 542,310 kilometres (336,980 miles) as of 2018[update].[209] Jakarta has the most extended bus rapid transit system globally, boasting 251.2 kilometres (156.1 miles) in 13 corridors and ten cross-corridor routes.[210] Rickshaws such as bajaj and becak and share taxis such as Angkot and Minibus are a regular sight in the country.

Most railways are in Java, and partly Sumatra and Sulawesi,[211] used for freight and passenger transport, such as local commuter rail services (mainly in Greater Jakarta and Yogyakarta–Solo) complementing the inter-city rail network in several cities. In the late 2010s, Jakarta and Palembang were the first cities in Indonesia to have rapid transit systems, with more planned for other cities in the future.[212] In 2023, a high-speed rail called Whoosh connecting the cities of Jakarta and Bandung commenced operations, a first for Southeast Asia and the Southern Hemisphere.[213]

Indonesia's largest airport, Soekarno–Hatta International Airport, is among the busiest in the Southern Hemisphere, serving 49 million passengers in 2023. Ngurah Rai International Airport and Juanda International Airport are the country's second-and third-busiest airport, respectively. Garuda Indonesia, the country's flag carrier since 1949, is one of the world's leading airlines and a member of the global airline alliance SkyTeam. The Port of Tanjung Priok is the busiest and most advanced Indonesian port,[214] handling more than 50% of Indonesia's trans-shipment cargo traffic.

In 2019, Indonesia produced 4,999 terawatt-hours (17.059 quadrillion British thermal units) and consumed 2,357 terawatt-hours (8.043 quadrillion British thermal units) worth of energy.[215] The country has substantial energy resources, including 22 billion barrels (3.5 billion cubic metres) of conventional oil and gas reserves (of which about 4 billion barrels are recoverable), 8 billion barrels of oil-equivalent of coal-based methane (CBM) resources, and 28 billion tonnes of recoverable coal.[216]

In late 2020, Indonesia's total national installed power generation capacity stands at 72,750.72 MW.[217] Although reliance on domestic coal and imported oil has increased between 2010 and 2019,[215][218] Indonesia has seen progress in renewable energy, with hydropower and geothermal being the most abundant sources that account for more than 8% in the country's energy mix.[215] A prime example of the former is the country's largest dam, Jatiluhur, which has an installed capacity of 186.5 MW that feeds into the Java grid managed by the State Electricity Company (Perusahaan Listrik Negara, PLN). Furthermore, Indonesia has the potential for solar, wind, biomass and ocean energy,[219] although as of 2021, power generation from these sources remain small.

The 2020 census recorded Indonesia's population as 270.2 million, the fourth largest in the world, with a moderately high population growth rate of 1.25%.[220] Java is the world's most populous island,[221] where 56% of the country's population lives.[6] The population density is 141 people per square kilometre (370 people/sq mi),[6] ranking 88th in the world, although Java has a population density of 1,067 people per square kilometre (2,760 people/sq mi). In 1961, the first post-colonial census recorded a total of 97 million people.[222] It is expected to grow to around 295 million by 2030 and 321 million by 2050.[223] The country currently possesses a relatively young population, with a median age of 30.2 years (2017 estimate).[77]

The spread of the population is uneven throughout the archipelago, with a varying habitats and levels of development, ranging from the megacity of Jakarta to uncontacted tribes in Papua.[224] As of 2017, about 54.7% of the population lives in urban areas.[225] Jakarta is the country's primate city and the second-most populous urban area globally, with over 34 million residents.[226] About 8 million Indonesians live overseas; most settled in Malaysia, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, South Africa, Singapore, Hong Kong, the United States, and Australia.[227]

Indonesia is an ethnically diverse country, with around 1,300 distinct native ethnic groups.[2] Most Indonesians are descended from Austronesian peoples whose languages had origins in Proto-Austronesian, which possibly originated in what is now Taiwan. Another major grouping is the Melanesians, who inhabit eastern Indonesia (the Maluku Islands, Western New Guinea and the eastern part of the Lesser Sunda Islands).[23][228][229][230]

The Javanese are the largest ethnic group, constituting 40.2% of the population,[2] and are politically dominant.[231] They are predominantly located in the central to eastern parts of Java and also in sizeable numbers in most provinces. The Sundanese are the next largest group (15.4%), followed by Malay, Batak, Madurese, Betawi, Minangkabau, and Bugis people.[e] A sense of Indonesian nationhood exists alongside strong regional identities.[232]

The country's official language is Indonesian, a variant of Malay based on its prestige dialect, which had been the archipelago's lingua franca for centuries. It was promoted by nationalists in the 1920s and achieved official status in 1945 under the name Bahasa Indonesia.[233] Due to centuries-long contact with other languages, it is rich in local and foreign influences.[f] Nearly every Indonesian speaks the language due to its widespread use in education, academics, communications, business, politics, and mass media. Most Indonesians also speak at least one of more than 700 local languages,[1] often as their first language. Most belong to the Austronesian language family, while over 270 Papuan languages are spoken in eastern Indonesia.[1] Of these, Javanese is the most widely spoken[77] and has co-official status in the Special Region of Yogyakarta.[237]

In 1930, Dutch and other Europeans (Totok), Eurasians, and derivative people like the Indos, numbered 240,000 or 0.4% of the total population.[238] Historically, they constituted only a tiny fraction of the native population and remain so today. Also, the Dutch language never had a substantial number of speakers or official status despite the Dutch presence for almost 350 years.[239] The small minorities that can speak it or Dutch-based creole languages fluently are the aforementioned ethnic groups and descendants of Dutch colonisers. This reflected the Dutch colonial empire's primary purpose, which was commercial exchange as opposed to sovereignty over homogeneous landmasses.[240] Today, there is some degree of fluency by either educated members of the oldest generation or legal professionals,[241] as specific law codes are still only available in Dutch.[242]

Although the government officially recognises only six religions: Islam, Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism,[243][244] and indigenous religions for administrative purpose,[244][245] religious freedom is guaranteed in the country's constitution.[246][128] With 231 million adherents (86.7%) in 2018, Indonesia is the world's most populous Muslim-majority country,[247][248] with Sunnis being the majority (99%).[249] The Shias and Ahmadis, respectively, constitute 1% (1–3 million) and 0.2% (200,000–400,000) of Muslims.[244][250] About 10% of Indonesians are Christians, who form the majority in several provinces in eastern Indonesia.[251] Most Hindus are Balinese,[252] and most Buddhists are Chinese Indonesians.[253]

The natives of the Indonesian archipelago originally practised indigenous animism and dynamism, beliefs that are common to Austronesian peoples.[254] They worshipped and revered ancestral spirits and believed that supernatural spirits (hyang) might inhabit certain places such as large trees, stones, forests, mountains, or sacred sites.[254] Examples of Indonesian native belief systems include the Sundanese Sunda Wiwitan, Dayak's Kaharingan, and the Javanese Kejawèn. They have significantly impacted how other faiths are practised, evidenced by a large proportion of people—such as the Javanese abangan, Balinese Hindus, and Dayak Christians—practising a less orthodox, syncretic form of their religion.[255]

Hindu influences reached the archipelago as early as the first century CE.[256] The Sundanese Kingdom of Salakanagara in western Java around 130 was the first historically recorded Indianised kingdom in the archipelago.[257] Buddhism arrived around the 6th century,[258] and its history in Indonesia is closely related to that of Hinduism, as some empires based on Buddhism had their roots around the same period. The archipelago has witnessed the rise and fall of powerful and influential Hindu and Buddhist empires such as Majapahit, Sailendra, Srivijaya, and Mataram. Though no longer a majority, Hinduism and Buddhism remain to have a substantial influence on Indonesian culture.[259][260]

Islam was introduced by Sunni traders of the Shafi'i school as well as Sufi traders from the Indian subcontinent and southern Arabia as early as the 8th century CE.[261][262] For the most part, Islam overlaid and mixed with existing cultural and religious influences, resulting in a distinct form of Islam (santri).[32][263] Trade, Islamic missionary activity such as by the Wali Sanga and Chinese explorer Zheng He, and military campaigns by several sultanates helped accelerate the spread of Islam.[264][265] By the end of the 16th century, it had supplanted Hinduism and Buddhism as the dominant religion of Java and Sumatra.

Catholicism was brought by Portuguese traders and missionaries such as Jesuit Francis Xavier, who visited and baptised several thousand locals.[266][267] Its spread faced difficulty due to the Dutch East India Company policy of banning the religion and the Dutch hostility due to the Eighty Years' War against Catholic Spain's rule. Protestantism is mostly a result of Calvinist and Lutheran missionary efforts during the Dutch colonial era.[268][269][270] Although they are the most common branch, there is a multitude of other denominations elsewhere in the country.[271]

There is a small Jewish presence in the archipelago, mostly the descendants of Dutch and Iraqi Jews, and some local converts. Most of them left in the decades after Indonesian independence, with only a tiny number of Jews remain today mostly in Jakarta, Manado, and Surabaya.[272] Judaism was once officially listed as Hebrani under the Sukarno government but ceased to be recorded separately like other religions with few adherents since 1965.[273] Presently, one of the only remaining Synagogue in Indonesia is Sha'ar Hashamayim Synagogue located in Tondano, North Sulawesi, around 31 km from Manado.

At the national and local level, Indonesia's political leadership and civil society groups have played a crucial role in interfaith relations, both positively and negatively. The invocation of the first principle of Indonesia's philosophical foundation, Pancasila[274][275] (i.e. the belief in the one and only God), often serves as a reminder of religious tolerance,[276] though instances of intolerance have occurred.[277][73] An overwhelming majority of Indonesians consider religion to be essential and an integral part of life.[278][279]

Education is compulsory for 12 years.[280] Parents can choose between state-run, non-sectarian schools or private or semi-private religious (usually Islamic) schools, supervised by the ministries of Education and Religion, respectively.[281] Private international schools that do not follow the national curriculum are also available. The enrolment rate is 93% for primary education, 79% for secondary education, and 36% for tertiary education (2018).[282] The literacy rate is 96% (2018), and the government spends about 3.6% of GDP (2015) on education.[282] In 2018, there were 4,670 higher educational institutions in Indonesia, with most (74%) located in Sumatra and Java.[283][284] According to the QS World University Rankings, Indonesia's top universities are the University of Indonesia, Gadjah Mada University and the Bandung Institute of Technology.[285]

Government expenditure on healthcare was about 3.3% of GDP in 2016.[286] As part of an attempt to achieve universal health care, the government launched the National Health Insurance (Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional, JKN) in 2014.[287] It includes coverage for a range of services from the public and also private firms that have opted to join the scheme. Despite remarkable improvements in recent decades, such as rising life expectancy (from 62.3 years in 1990 to 71.7 years in 2019)[288] and declining child mortality (from 84 deaths per 1,000 births in 1990 to 23.9 deaths in 2019),[289] challenges remain, including maternal and child health, low air quality, malnutrition, high rate of smoking, and infectious diseases.[290]

In the economic sphere, there is a gap in wealth, unemployment rate, and health between densely populated islands and economic centres (such as Sumatra and Java) and sparsely populated, disadvantaged areas (such as Maluku and Papua).[291][292] This is created by a situation in which nearly 80% of Indonesia's population lives in the western parts of the archipelago[293] and yet grows slower than the rest of the country.

In the social arena, numerous cases of racism and discrimination, especially against Chinese Indonesians and Papuans, have been well documented throughout Indonesia's history.[294][295] Such cases have sometimes led to violent conflicts, most notably the May 1998 riots and the Papua conflict, which has continued since 1962. LGBT people also regularly face challenges. Although LGBT issues have been relatively obscure, the 2010s (especially after 2016) has seen a rapid surge of anti-LGBT rhetoric, putting LGBT Indonesians into a frequent subject of intimidation, discrimination, and even violence.[296][297] In addition, Indonesia has been reported to have sizeable numbers of child and forced labourers, with the former being prevalent in the palm oil and tobacco industries, while the latter in the fishing industry.[298][299]

The cultural history of the Indonesian archipelago spans more than two millennia. Influences from the Indian subcontinent, mainland China, the Middle East, Europe,[300][301] Melanesian and Austronesian peoples have historically shaped the cultural, linguistic and religious makeup of the archipelago. As a result, modern-day Indonesia has a multicultural, multilingual and multi-ethnic society,[1][2] with a complex cultural mixture that differs significantly from the original indigenous cultures. Indonesia currently holds thirteen items of UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage, including a wayang puppet theatre, kris, batik,[302] pencak silat, angklung, gamelan, and the three genres of traditional Balinese dance.[303]

Indonesian arts include both age-old art forms developed through centuries and recently developed contemporary art. Despite often displaying local ingenuity, Indonesian arts have absorbed foreign influences—most notably from India, the Arab world, China and Europe, due to contacts and interactions facilitated, and often motivated by trade.[304] Painting is an established and developed art in Bali, where its people are famed for their artistry. Their painting tradition started as classical Kamasan or Wayang style visual narrative, derived from visual art discovered on candi bas reliefs in eastern Java.[305]

There have been numerous discoveries of megalithic sculptures in Indonesia.[306] Subsequently, tribal art has flourished within the culture of Nias, Batak, Asmat, Dayak and Toraja.[307][308] Wood and stone are common materials used as the media for sculpting among these tribes. Between the 8th and 15th centuries, the Javanese civilisation developed refined stone sculpting art and architecture influenced by the Hindu-Buddhist Dharmic civilisation. The temples of Borobudur and Prambanan are among the most famous examples of the practice.[309]

As with the arts, Indonesian architecture has absorbed foreign influences that have brought cultural changes and profound effects on building styles and techniques. The most dominant has traditionally been Indian; however, Chinese, Arab, and European influences have also been significant. Traditional carpentry, masonry, stone and woodwork techniques and decorations have thrived in vernacular architecture, with numbers of traditional houses' (rumah adat) styles that have been developed. The traditional houses and settlements vary by ethnic group, and each has a specific custom and history.[310] Examples include Toraja's Tongkonan, Minangkabau's Rumah Gadang and Rangkiang, Javanese style Pendopo pavilion with Joglo style roof, Dayak's longhouses, various Malay houses, Balinese houses and temples, and also different forms of rice barns (lumbung).[citation needed]

The music of Indonesia predates historical records. Various indigenous tribes incorporate chants and songs accompanied by musical instruments in their rituals. Angklung, kacapi suling, gong, gamelan, talempong, kulintang, and sasando are examples of traditional Indonesian instruments. The diverse world of Indonesian music genres results from the musical creativity of its people and subsequent cultural encounters with foreign influences. These include gambus and qasida from the Middle East,[311] keroncong from Portugal,[312] and dangdut—one of Indonesia's most popular music genres—with notable Hindi influence as well as Malay orchestras.[313] Today, the Indonesian music industry enjoys both nationwide and regional popularity in Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei,[314][315] due to the common culture and mutual intelligibility between Indonesian and Malay.[316]

Indonesian dances have a diverse history, with more than 3,000 original dances. Scholars believe that they had their beginning in rituals and religious worship.[317] Examples include war dances, a dance of witch doctors, and a dance to call for rain or any agricultural rituals such as Hudoq. Indonesian dances derive their influences from the archipelago's prehistoric and tribal, Hindu-Buddhist, and Islamic periods. Recently, modern dances and urban teen dances have gained popularity due to the influence of Western culture and those of Japan and South Korea to some extent. However, various traditional dances, including those of Java, Bali and Dayak, remain a living and dynamic tradition.[318]

Indonesia has various clothing styles due to its long and rich cultural history. The national costume originates from the country's indigenous culture and traditional textile traditions. The Javanese Batik and Kebaya[319] are arguably Indonesia's most recognised national costumes, though they have Sundanese and Balinese origins as well.[320] Each province has a representation of traditional attire and dress,[300] such as Ulos of Batak from North Sumatra; Songket of Malay and Minangkabau from Sumatra; and Ikat of Sasak from Lombok. People wear national and regional costumes during traditional weddings, formal ceremonies, music performances, government and official occasions,[320] and they vary from traditional to modern attire.

Wayang, the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese shadow puppet theatre displays several legends from Hindu mythology such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.[321] Other forms of local drama include the Javanese Ludruk and Ketoprak, the Sundanese Sandiwara, Betawi Lenong,[322][323] and various Balinese dance dramas. They incorporate humour and jest and often involve audiences in their performances.[324] Some theatre traditions also include music, dancing and silat martial art, such as Randai from the Minangkabau people of West Sumatra. It is usually performed for traditional ceremonies and festivals[325][326] and based on semi-historical Minangkabau legends and love story.[326] Modern performing art also developed in Indonesia with its distinct style of drama. Notable theatre, dance, and drama troupe such as Teater Koma are famous as it often portrays social and political satire of Indonesian society.[327]

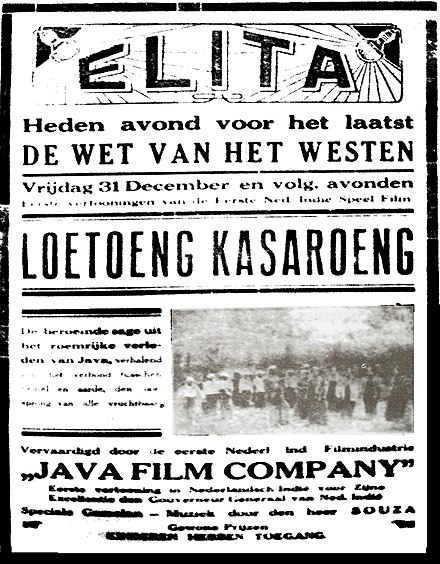

The first film produced in the archipelago was Loetoeng Kasaroeng,[328] a silent film by Dutch director L. Heuveldorp. The film industry expanded after independence, with six films made in 1949 rising to 58 in 1955. Usmar Ismail, who made significant imprints in the 1950s and 1960s, is generally considered the pioneer of Indonesian films.[329] The latter part of the Sukarno era saw the use of cinema for nationalistic, anti-Western purposes, and foreign films were subsequently banned, while the New Order used a censorship code that aimed to maintain social order.[330] Production of films peaked during the 1980s, although it declined significantly in the next decade.[328] Notable films in this period include Pengabdi Setan (1980), Nagabonar (1987), Tjoet Nja' Dhien (1988), Catatan Si Boy (1989), and Warkop's comedy films.

Independent film making was a rebirth of the film industry since 1998, when films started addressing previously banned topics, such as religion, race, and love.[330] Between 2000 and 2005, the number of films released each year steadily increased.[331] Riri Riza and Mira Lesmana were among the new generation of filmmakers who co-directed Kuldesak (1999), Petualangan Sherina (2000), Ada Apa dengan Cinta? (2002), and Laskar Pelangi (2008). In 2022, KKN di Desa Penari smashed box office records, becoming the most-watched Indonesian film with 9.2 million tickets sold.[332] Indonesia has held annual film festivals and awards, including the Indonesian Film Festival (Festival Film Indonesia) held intermittently since 1955. It hands out the Citra Award, the film industry's most prestigious award. From 1973 to 1992, the festival was held annually and then discontinued until its revival in 2004.

Media freedom increased considerably after the fall of the New Order, during which the Ministry of Information monitored and controlled domestic media and restricted foreign media.[333] The television market includes several national commercial networks and provincial networks that compete with public TVRI, which held a monopoly on TV broadcasting from 1962 to 1989. By the early 21st century, the improved communications system had brought television signals to every village, and people can choose from up to 11 channels.[334] Private radio stations carry news bulletins while foreign broadcasters supply programmes. The number of printed publications has increased significantly since 1998.[334]

Like other developing countries, Indonesia began developing Internet in the early 1990s. Its first commercial Internet service provider, PT. Indo Internet began operation in Jakarta in 1994.[335] The country had 171 million Internet users in 2018, with a penetration rate that keeps increasing annually.[336] Most are between the ages of 15 and 19 and depend primarily on mobile phones for access, outnumbering laptops and computers.[337]

The oldest evidence of writing in the Indonesian archipelago is a series of Sanskrit inscriptions dated to the 5th century. Many of Indonesia's peoples have firmly rooted oral traditions, which help define and preserve their cultural identities.[339] In written poetry and prose, several traditional forms dominate, mainly syair, pantun, gurindam, hikayat and babad. Examples of these forms include Syair Abdul Muluk, Hikayat Hang Tuah, Sulalatus Salatin, and Babad Tanah Jawi.[340]

Early modern Indonesian literature originates in the Sumatran tradition.[341][342] Literature and poetry flourished during the decades leading up to and after independence. Balai Pustaka, the government bureau for popular literature, was instituted in 1917 to promote the development of indigenous literature. Many scholars consider the 1950s and 1960s to be the Golden Age of Indonesian Literature.[343] The style and characteristics of modern Indonesian literature vary according to the dynamics of the country's political and social landscape,[343] most notably the war of independence in the second half of the 1940s and the anti-communist mass killings in the mid-1960s.[344] Notable literary figures of the modern era include Hamka, Chairil Anwar, Mohammad Yamin, Merari Siregar, Marah Roesli, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, and Ayu Utami.

Indonesian cuisine is one of the world's most diverse, vibrant, and colourful, full of intense flavour.[345] Many regional cuisines exist, often based upon indigenous culture and foreign influences such as Chinese, African, European, Middle Eastern, and Indian precedents.[346] Rice is the leading staple food and is served with side dishes of meat and vegetables. Spices (notably chilli), coconut milk, fish and chicken are fundamental ingredients.[347]

Some popular dishes such as nasi goreng, gado-gado, sate, and soto are ubiquitous and considered national dishes. The Ministry of Tourism, however, chose tumpeng as the official national dish in 2014, describing it as binding the diversity of various culinary traditions.[348] Other popular dishes include rendang, one of the many Minangkabau cuisines along with dendeng and gulai. Another fermented food is oncom, similar in some ways to tempeh but uses a variety of bases (not only soy), created by different fungi, and is prevalent in West Java.[349]

Badminton and football are the most popular sports in Indonesia. Indonesia is among the few countries that have won the Thomas and Uber Cup, the world team championship of men's and women's badminton. Along with weightlifting, it is the sport that contributes the most to Indonesia's Olympic medal tally. Liga 1 is the country's premier football club league. On the international stage, Indonesia was the first Asian team to participate in the FIFA World Cup in 1938 as the Dutch East Indies.[350] On a regional level, Indonesia won a bronze medal at the 1958 Asian Games as well as three gold medals at the 1987, 1991 and 2023 Southeast Asian Games (SEA Games). Indonesia's first appearance at the AFC Asian Cup was in 1996.[351]

Other popular sports include boxing and basketball, which were part of the first National Games (Pekan Olahraga Nasional, PON) in 1948.[352] Sepak takraw and karapan sapi (bull racing) in Madura are some examples of Indonesia's traditional sports. In areas with a history of tribal warfare, mock fighting contests are held, such as caci in Flores and pasola in Sumba. Pencak Silat is an Indonesian martial art that, in 2018, became one of the sporting events in the Asian Games, with Indonesia appearing as one of the leading competitors. In Southeast Asia, Indonesia is one of the top sports powerhouses, topping the SEA Games medal table ten times since 1977,[353] most recently in 2011.[354]

5°S 120°E / 5°S 120°E / -5; 120