Детройт ( / d ɪ ˈ t r ɔɪ t / , dih- TROYT ; локально также / ˈ d iː t r ɔɪ t / , DEE -troyt ) [8] является самым густонаселенным городом в американском штате Мичиган . Это крупнейший город США на границе с Канадой и административный центр округа Уэйн . Население Детройта по переписи 2020 года составляло 639 111 человек [9] , что делает его 26 -м по численности населения городом в Соединенных Штатах. Район Метро Детройт , где проживает 4,3 миллиона человек, является вторым по величине на Среднем Западе после столичного района Чикаго и 14-м по величине в Соединенных Штатах. Являясь значительным культурным центром, Детройт известен своим вкладом в музыку, искусство, архитектуру и дизайн, а также своим историческим автомобильным прошлым. [10] [11]

В 1701 году Антуан де ла Мот Кадиллак и Альфонс де Тонти основали форт Пончартрейн в Детройте . В конце 19-го и начале 20-го века он стал важным промышленным узлом в центре региона Великих озер . Население города выросло до четвертого по величине в стране к 1920 году после Нью-Йорка , Чикаго и Филадельфии , с расширением автомобильной промышленности в начале 20-го века. [12] Река Детройт стала самым загруженным коммерческим узлом в мире, поскольку она перевозила более 65 миллионов тонн грузов каждый год. В середине 20-го века Детройт вошел в состояние городского упадка , которое продолжается и по сей день в результате промышленной реструктуризации, потери рабочих мест в автомобильной промышленности и быстрой пригородизации . С момента достижения пика в 1,85 миллиона человек по переписи 1950 года население Детройта сократилось более чем на 65 процентов. [9] В 2013 году Детройт стал крупнейшим городом США, объявившим себя банкротом , из которого он успешно вышел в декабре 2014 года. [13]

Детройт — порт на реке Детройт, одном из четырёх главных проливов , соединяющих систему Великих озёр с проливом Святого Лаврентия . Город является якорем третьей по величине региональной экономики на Среднем Западе и 16-й по величине в США. [14] Детройт наиболее известен как центр автомобильной промышленности США , а « большая тройка » автопроизводителей — General Motors , Ford и Stellantis North America ( Chrysler ) — все имеют штаб-квартиры в Метро Детройт. [15] Аэропорт Детройт Метрополитен является одним из важнейших аэропортов-хабов в США. Детройт и соседний с ним канадский город Виндзор образуют второй по загруженности международный перевалочный пункт в Северной Америке после Сан-Диего–Тихуана . [16]

Разнообразная культура Детройта оказала как местное, так и международное влияние, особенно в музыке , город дал начало жанрам Motown и техно и сыграл важную роль в развитии джаза , хип-хопа , рока и панка . Быстрый рост Детройта в годы его бума привел к появлению уникального в мировом масштабе фонда архитектурных памятников и исторических мест . С 2000-х годов усилия по сохранению культуры позволили спасти множество архитектурных произведений и провести несколько масштабных ревитализаций , включая реставрацию нескольких исторических театров и развлекательных заведений, реконструкцию высотных зданий , строительство новых спортивных стадионов и проект по восстановлению набережной. Детройт, становящийся все более популярным туристическим направлением , ежегодно посещают 16 миллионов человек. [17] В 2015 году Детройт был назван ЮНЕСКО « Городом дизайна » , первым и единственным городом США, получившим такое обозначение. [18]

Детройт назван в честь реки Детройт , соединяющей озеро Гурон с озером Эри . Название происходит от французского слова détroit, означающего « пролив », поскольку город был расположен на узком водном проходе, соединяющем два озера. Река была известна как le détroit du Lac Érié на французском языке, что означает « пролив озера Эри » . [19] [20] В историческом контексте пролив включал реку Сент-Клер , озеро Сент-Клер и реку Детройт. [21] [22]

Королевство Франция 1701–1760 Королевство Великобритания 1760–1783 Соединенные Штаты 1783-1812 Соединенное Королевство 1812–1813 Соединенные Штаты 1813–настоящее время

Палеоиндейцы населяли районы около Детройта еще 11 000 лет назад, включая культуру, называемую строителями курганов . [23] К 17 веку регион был заселен народами гуронов , одава , потаватоми и ирокезов . [24] Этот район известен народу анишинаабе как Waawiiyaataanong , что переводится как «там, где вода изгибается». [25]

Первые европейцы не проникали в регион и не достигли проливов Детройта, пока французские миссионеры и торговцы не обошли Ирокезскую лигу, с которой они воевали в 1630-х годах. [26] Гуроны и нейтральные народы удерживали северную сторону озера Эри до 1650-х годов, пока ирокезы не вытеснили их и народ Эри от озера и его богатых бобров притоков во время Бобровых войн 1649–1655 годов. [26] К 1670-м годам ослабленные войной ирокезы предъявили права на охотничьи угодья вплоть до долины реки Огайо в северном Кентукки [26] и поглотили многие другие ирокезские народы после победы над ними в войне. [26] В течение следующих ста лет практически ни одно британское или французское действие не рассматривалось без консультации с ирокезами или рассмотрения их вероятной реакции. [26] Когда война с французами и индейцами привела к изгнанию Королевства Франции из Канады, это устранило одно препятствие для миграции американских колонистов на запад. [27]

Британские переговоры с ирокезами оказались критическими и привели к политике короны, ограничивающей поселения ниже Великих озер и к западу от Аллеганских гор . Многие колониальные американские потенциальные переселенцы возмущались этим ограничением и стали сторонниками Американской революции . Рейды 1778 года и последовавшая за ними решительная экспедиция Салливана 1779 года вновь открыли Огайо для эмиграции на запад, которая началась почти сразу же. К 1800 году белые поселенцы устремились на запад. [28]

24 июля 1701 года французский исследователь Антуан де ла Мот Кадиллак со своим лейтенантом Альфонсом де Тонти и более чем сотней других поселенцев начали строительство небольшого форта на северном берегу реки Детройт. Кадиллак назвал поселение Форт Пончартрен дю Детройт [29] в честь Луи Фелипо, графа де Пончартрена , государственного секретаря военно-морского флота при Людовике XIV [ 30] Сент-Анн-де-Детруа был основан 26 июля и является вторым старейшим непрерывно действующим римско-католическим приходом в Соединенных Штатах [31] Франция предлагала колонистам бесплатную землю, чтобы привлечь семьи в Детройт; когда в 1765 году население достигло 800 человек, оно стало крупнейшим европейским поселением между Монреалем и Новым Орлеаном , оба также французскими поселениями, в бывших колониях Новая Франция и Ла-Луизиана соответственно. [32]

К 1773 году, после присоединения англо-американских поселенцев, население Детройта составляло 1400 человек. К 1778 году его население достигло 2144 человек, и он стал третьим по величине городом в провинции Квебек с момента захвата британцами французских колоний после их победы в Семилетней войне . [33]

Экономика региона основывалась на прибыльной торговле пушниной , в которой многочисленные коренные американцы играли важную роль в качестве охотников и торговцев. Сегодня флаг Детройта отражает его французское колониальное наследие. Потомки самых первых французских и франко-канадских поселенцев сформировали сплоченное сообщество, которое постепенно было вытеснено в качестве доминирующего населения после того, как в начале 19 века прибыло больше англо-американских поселенцев с американской миграцией на запад. Проживая вдоль берегов озера Сент-Клер и к югу от Монро и пригородов ниже по течению, этнические франко-канадцы Детройта, также известные как «французы-мускульчи» в связи с торговлей пушниной, остаются субкультурой в регионе в 21 веке. [34] [35]

Во время Франко-индейской войны (1754–63) — североамериканского фронта Семилетней войны между Британией и Францией — британские войска захватили поселение в 1760 году и сократили его название до Детройта. Несколько региональных индейских племен, таких как потоватоми , оджибве и гуроны, начали войну Понтиака в 1763 году и осадили Форт Детройт , но не смогли его захватить. Потерпев поражение, Франция уступила свои территории в Северной Америке к востоку от Миссисипи Великобритании после войны. [36]

После Американской войны за независимость и создания Соединенных Штатов в качестве независимой страны, Великобритания уступила Детройт вместе с другими территориями в этом районе по Договору Джея , который установил северную границу с ее колонией Канадой. [37] Великий пожар 1805 года уничтожил большую часть поселения Детройт, в котором в основном были деревянные здания. Единственными уцелевшими сооружениями были один каменный форт, речной склад и кирпичные трубы бывших деревянных домов. [38] Из 600 жителей Детройта в этом районе никто не погиб в огне. [39] Наследие пожара 1805 года живет во многих аспектах современного наследия Детройта. Девиз города «Speramus Meliora; Resurget Cineribus» был придуман отцом Габриэлем Ричардом , когда он смотрел на руины города после пожара. [40] [41] Городская печать, разработанная Дж. О. Льюисом в 1827 году, напрямую изображает Великий пожар 1805 года. Две женщины стоят на переднем плане, а слева город горит на заднем плане, и женщина плачет над разрушением. Женщина справа утешает ее, указывая на новый город, который поднимется на ее месте. [42] Городская печать также образует центр флага города.

С 1805 по 1847 год Детройт был столицей Мичигана как территории и как штата. Уильям Халл , командующий Соединённых Штатов в Детройте, сдался без боя британским войскам и их союзникам из числа коренных американцев во время войны 1812 года при осаде Детройта , полагая, что его силы значительно превосходят численностью. Битва при Френчтауне была частью усилий США по возвращению города, и американские войска понесли самые большие потери среди всех сражений войны. Эта битва увековечена в Национальном парке битвы на реке Рэйзин к югу от Детройта в округе Монро . Детройт был отбит Соединёнными Штатами позже в том же году. [43]

Поселение было включено в качестве города в 1815 году. [44] По мере того, как город расширялся, был принят радиальный геометрический план улиц, разработанный главным судьей Августом Б. Вудвордом , с большими бульварами, как в Париже . [45] В 1817 году Вудворд продолжил основывать Католепистемиаду , или Университет Мичигана в городе. Задуманная как централизованная система школ, библиотек и других культурных и научных учреждений для Территории Мичиган, Католепистемиада превратилась в современный Университет Мичигана.

До Гражданской войны в США доступ города к границе Канады и США делал его ключевым пунктом для рабов-беженцев, обретавших свободу на Севере по Подземной железной дороге . Многие переправлялись через реку Детройт в Канаду, чтобы избежать преследования ловцов рабов. [46] [44] По оценкам, от 20 000 до 30 000 афроамериканских беженцев поселились в Канаде. [47] Джордж Дебатист считался «президентом» Детройтской подземной железной дороги, Уильям Ламберт — «вице-президентом» или «секретарем», а Лора Смит Хэвиленд — «суперинтендантом». [48]

Многочисленные мужчины из Детройта добровольно сражались за Союз во время Гражданской войны, включая 24-й Мичиганский пехотный полк. Он был частью Железной бригады , которая сражалась с отличием и понесла 82% потерь в битве при Геттисберге в 1863 году. Когда Первый добровольческий пехотный полк прибыл для укрепления Вашингтона, округ Колумбия , президент Авраам Линкольн , как говорят, сказал: «Слава Богу за Мичиган!» Джордж Армстронг Кастер возглавлял Мичиганскую бригаду во время Гражданской войны и называл их «Росомахами». [49]

В конце 19 века богатые промышленные и судоходные магнаты заказали проектирование и строительство нескольких особняков Позолоченного века к востоку и западу от нынешнего центра города, вдоль главных проспектов плана Вудворда. Самым заметным среди них был дом Дэвида Уитни по адресу 4421 Вудворд Авеню , и Гранд Авеню стала излюбленным адресом для особняков. В этот период некоторые называли Детройт «Парижем Запада» за его архитектуру, большие проспекты в парижском стиле и за бульвар Вашингтона, недавно электрифицированный Томасом Эдисоном . [44] Город неуклонно рос с 1830-х годов с ростом судоходства, судостроения и обрабатывающей промышленности. Стратегически расположенный вдоль водного пути Великих озер, Детройт превратился в крупный порт и транспортный узел. [ требуется ссылка ]

В 1896 году процветающая торговля каретами побудила Генри Форда построить свой первый автомобиль в арендованной мастерской на Мак-авеню. В этот период роста Детройт расширил свои границы, присоединив все или часть нескольких близлежащих деревень и поселков. [50]

В 1903 году Генри Форд основал Ford Motor Company . Производство Ford, а также пионеров автомобилестроения Уильяма К. Дюранта , Хораса и Джона Додж, Джеймса и Уильяма Паккарда и Уолтера Крайслера , в начале 20-го века обеспечило Детройту статус мировой автомобильной столицы. [44] Рост автомобильной промышленности отразился на изменениях в бизнесе по всему Среднему Западу и стране, с развитием гаражей для обслуживания автомобилей и заправочных станций, а также заводов по производству деталей и шин. [ необходима ссылка ] Благодаря бурно развивающейся автомобильной промышленности Детройт стал четвертым по величине городом в стране к 1920 году после Нью-Йорка , Чикаго и Филадельфии . [51]

В 1907 году река Детройт перевезла 67 292 504 тонн грузов через Детройт в разные точки мира. Для сравнения, Лондон перевез 18 727 230 тонн, а Нью-Йорк — 20 390 953 тонн. В 1908 году The Detroit News назвала реку «Величайшей торговой артерией на Земле». Запрет на алкоголь с 1920 по 1933 год привел к тому, что река Детройт стала основным каналом для контрабанды нелегальных канадских спиртных напитков. [12]

С быстрым ростом числа промышленных рабочих на автомобильных заводах, профсоюзы, такие как Американская федерация труда и Объединенные работники автомобильной промышленности (UAW), боролись за организацию рабочих, чтобы добиться для них лучших условий труда и заработной платы. Они инициировали забастовки и другие тактики в поддержку улучшений, таких как 8-часовой рабочий день/40-часовая рабочая неделя , повышение заработной платы, большие льготы и улучшение условий труда . Рабочий активизм в те годы увеличил влияние профсоюзных лидеров в городе, таких как Джимми Хоффа из Teamsters и Уолтер Рейтер из UAW. [52]

Детройт, как и многие места в Соединенных Штатах, в 20 веке развился расовый конфликт и дискриминация после быстрых демографических изменений, когда сотни тысяч новых рабочих были привлечены в промышленный город. Великая миграция привела сельских чернокожих с Юга; их превосходили по численности южные белые, которые также мигрировали в город. Иммиграция привела южных и восточных европейцев католической и иудейской веры; эти новые группы конкурировали с коренными белыми за рабочие места и жилье в процветающем городе. [ необходима цитата ]

Детройт был одним из главных городов Среднего Запада, который стал местом драматического городского возрождения Ку -клукс-клана (ККК), начавшегося в 1915 году. «К 1920-м годам город стал оплотом ККК», члены которого в первую очередь выступали против католических и еврейских иммигрантов, но также практиковали дискриминацию в отношении чернокожих американцев. [53] Даже после упадка ККК в конце 1920-х годов, Черный легион , тайная группа мстителей, действовала в районе Детройта в 1930-х годах. Одна треть из ее предполагаемых 20 000-30 000 членов в Мичигане базировались в городе. Он был разгромлен после многочисленных судебных преследований после похищения и убийства в 1936 году Чарльза Пула, католического организатора из федерального Управления общественных работ . Около 49 человек из Черного легиона были осуждены за многочисленные преступления, многие из которых были приговорены к пожизненному заключению за убийство. [54]

К 1940 году 80% актов Детройта содержали ограничительные положения, запрещающие афроамериканцам покупать дома, которые они могли себе позволить. Эта дискриминационная тактика оказалась успешной, поскольку большинство чернокожих в Детройте перебрались в полностью черные кварталы, такие как Блэк-Боттом и Парадайз-Вэлли. В то время белые люди все еще составляли около 90,4% населения города. [55] Белые жители нападали на черные дома: разбивали окна, устраивали пожары и взрывали бомбы. [56] [57]

В 1940-х годах была построена «первая в мире городская депрессивная автомагистраль» из когда-либо построенных, Davison [ 58] . Во время Второй мировой войны правительство поощряло переоснащение американской автомобильной промышленности в поддержку союзных держав , что привело к ключевой роли Детройта в американском арсенале демократии [59] . Рабочие места росли так быстро из-за наращивания обороны во время Второй мировой войны, что 400 000 человек мигрировали в город с 1941 по 1943 год, включая 50 000 чернокожих во второй волне Великой миграции и 350 000 белых, многие из которых были с Юга. Белые, включая этнических европейцев, опасались конкуренции со стороны черных за рабочие места и дефицита жилья. Федеральное правительство запретило дискриминацию в оборонной промышленности, но когда в июне 1943 года Packard повысил трех чернокожих до рабочих мест рядом с белыми на своих сборочных линиях, 25 000 белых рабочих ушли с работы. [60] Расовый бунт в Детройте 1943 года произошел в июне, через три недели после протеста завода Packard , начавшись со стычки в Belle Isle . Всего было убито 34 человека, 25 из них были черными, и большинство от рук белой полиции, в то время как 433 были ранены (75% из них были черными), и имущество стоимостью 2 миллиона долларов (стоимостью 30,4 миллиона долларов в 2020 году) было уничтожено. Бунтовщики двигались по городу, и молодые белые путешествовали по городу, чтобы напасть на более оседлых черных в их районе Paradise Valley . [61] [62]

Промышленные слияния в 1950-х годах, особенно в автомобильном секторе, увеличили олигополию в американской автомобильной промышленности. Детройтские производители, такие как Packard и Hudson, слились с другими компаниями и в конечном итоге исчезли. При пиковой численности населения в 1 849 568 человек, по переписи 1950 года , город был пятым по величине в Соединенных Штатах. [63]

В эту послевоенную эпоху автомобильная промышленность продолжала создавать возможности для многих афроамериканцев с Юга, которые продолжили свою Великую миграцию в Детройт и другие северные и западные города, чтобы избежать строгих законов Джима Кроу и политики расовой дискриминации Юга. Послевоенный Детройт был процветающим промышленным центром массового производства. Автомобильная промышленность составляла около 60% всей промышленности в городе, предоставляя пространство для множества отдельных процветающих предприятий, включая производство печей, пивоварение, производство мебели, нефтеперерабатывающие заводы, фармацевтическое производство и многое другое. Расширение рабочих мест создало уникальные возможности для чернокожих американцев, которые увидели новые высокие показатели занятости: в послевоенном Детройте число чернокожих, занятых в городе, увеличилось на 103%. Чернокожие американцы, иммигрировавшие в северные промышленные города с юга, по-прежнему сталкивались с жесткой расовой дискриминацией в сфере занятости. Расовая дискриминация удерживала рабочую силу и лучшие рабочие места преимущественно белыми, в то время как многие чернокожие жители Детройта занимали низкооплачиваемые рабочие места на фабриках. Несмотря на изменения в демографической ситуации, связанные с ростом черного населения города, полицейские силы Детройта, пожарная служба и другие городские должности продолжали занимать преимущественно белые жители. Это создало несбалансированную расовую динамику власти. [64]

Неравные возможности в сфере занятости привели к неравным возможностям в сфере жилья для большинства представителей черного сообщества: в условиях общего более низкого дохода и в условиях ответной реакции дискриминационной жилищной политики черное сообщество было ограничено более дешевым и качественным жильем в городе. Рост численности черного населения усилил нагрузку на нехватку жилья. Жилые площади, доступные черному сообществу, были ограничены, и в результате семьи часто толпились в антисанитарных, небезопасных и нелегальных кварталах. Такая дискриминация становилась все более очевидной в политике красной черты, проводимой банками и федеральными жилищными группами, которая почти полностью ограничивала возможности черных улучшать свое жилье и поощряла белых людей охранять расовое разделение, которое определяло их районы. В результате черным людям часто отказывали в банковских кредитах на получение лучшего жилья, а процентные ставки и арендная плата были несправедливо завышены, чтобы помешать им переехать в белые районы. Белые жители и политические лидеры в значительной степени выступали против притока черных жителей Детройта в белые районы, полагая, что их присутствие приведет к ухудшению условий в районе. Это увековечило циклический процесс исключения, который маргинализировал деятельность чернокожих жителей Детройта, заперев их в самых нездоровых и наименее безопасных районах города. [64]

Как и в других крупных американских городах в послевоенную эпоху, модернистская идеология планирования привела к строительству федерально субсидируемой, обширной системы автомагистралей и скоростных автострад вокруг Детройта, а неудовлетворенный спрос на новое жилье стимулировал пригородизацию; автомагистрали облегчили поездки на работу на автомобиле для жителей с более высоким доходом. Однако это строительство имело негативные последствия для многих городских жителей с низким доходом. Автомагистрали были построены через и полностью снесли кварталы бедных жителей и чернокожих общин, у которых было меньше политической власти, чтобы противостоять им. Районы были в основном с низким доходом, считались упадочными или состояли из старого жилья, в которое не хватало инвестиций из-за расовой красной черты, поэтому шоссе были представлены как своего рода городское обновление. Эти кварталы (такие как Black Bottom и Paradise Valley) были чрезвычайно важны для черных общин Детройта, предоставляя пространства для независимых черных предприятий и социальных/культурных организаций. Их разрушение привело к перемещению жителей, не принимая во внимание последствия разрушения функционирующих районов и предприятий. [64]

В 1956 году последняя интенсивно используемая линия электрического трамвая в Детройте , которая проходила вдоль Вудворд Авеню, была удалена и заменена автобусами на газовом топливе. Это была последняя линия того, что когда-то было 534-мильной сетью электрических трамваев. В 1941 году в часы пик трамвай ходил по Вудворд Авеню каждые 60 секунд. [65] [66]

Все эти изменения в транспортной системе района благоприятствовали развитию с низкой плотностью, ориентированному на автомобили, а не развитию с высокой плотностью городского населения. Промышленность также переместилась в пригороды, ища большие участки земли для одноэтажных фабрик. К 21 веку район метро Детройта превратился в один из самых обширных рынков труда в Соединенных Штатах; в сочетании с плохим общественным транспортом это привело к тому, что многие новые рабочие места оказались вне досягаемости городских рабочих с низким доходом. [67]

В 1950 году в городе проживало около трети населения штата. В течение следующих 60 лет население города сократилось до менее 10 процентов населения штата. За тот же период времени разросшаяся столичная зона выросла и стала вмещать более половины населения Мичигана. [44] Перемещение населения и рабочих мест подорвало налоговую базу Детройта. [ требуется цитата ]

В июне 1963 года преподобный Мартин Лютер Кинг-младший выступил с важной речью в рамках марша за гражданские права в Детройте, которая предвосхитила его речь « У меня есть мечта » в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия, два месяца спустя. В то время как движение за гражданские права добилось значительных федеральных законов о гражданских правах в 1964 и 1965 годах, давнее неравенство привело к столкновениям между полицией и чернокожей молодежью из неблагополучных районов города, которая хотела перемен. [68]

Сегодня днем мне приснился сон, что мои четверо маленьких детей, что мои четверо маленьких детей не вырастут в те же юные годы, в которые вырос я, но их будут судить по содержанию их характера, а не по цвету кожи... Сегодня вечером мне приснился сон, что однажды мы узнаем слова Джефферсона о том, что «все люди созданы равными, что они наделены своим Создателем определенными неотъемлемыми правами, среди которых — жизнь, свобода и стремление к счастью». У меня приснился сон...

— Мартин Лютер Кинг-младший (Речь на Великом марше в Детройте , июнь 1963 г. ) [69]

Давняя напряженность в Детройте достигла кульминации в беспорядках на Двенадцатой улице в июле 1967 года. Губернатор Джордж У. Ромни приказал Национальной гвардии Мичигана войти в Детройт, а президент Линдон Б. Джонсон направил войска армии США. Результатом стали 43 погибших, 467 раненых, более 7200 арестов и более 2000 разрушенных зданий, в основном в черных жилых и деловых районах. Тысячи малых предприятий закрылись навсегда или переехали в более безопасные районы. Пострадавший район лежал в руинах в течение десятилетий. [70] По данным Chicago Tribune , это был третий по стоимости бунт в Соединенных Штатах. [71]

18 августа 1970 года NAACP подала иск против должностных лиц штата Мичиган, включая губернатора Уильяма Милликена , обвинив в фактической сегрегации государственных школ. NAACP утверждала, что, хотя школы не были юридически сегрегированы, город Детройт и окружающие его округа приняли политику поддержания расовой сегрегации в государственных школах. NAACP также предположила прямую связь между несправедливой жилищной практикой и образовательной сегрегацией, поскольку состав учащихся в школах следовал сегрегированным районам. [72] Окружной суд в своем постановлении возложил ответственность за сегрегацию на все уровни правительства. Апелляционный суд шестого округа подтвердил часть решения, постановив, что ответственность за интеграцию в сегрегированном столичном районе лежит на штате . [73] Верховный суд США рассмотрел дело 27 февраля 1974 года. [72] Последующее решение по делу Милликен против Брэдли имело общенациональное влияние. В узком решении Верховный суд постановил, что школы являются предметом местного контроля, и пригороды не могут быть принуждены помогать в десегрегации школьного округа города. [74]

«Милликен, возможно, был самой большой упущенной возможностью того периода», — сказал Майрон Орфилд , профессор права в юридической школе Университета Миннесоты . «Если бы все пошло по-другому, это открыло бы дверь для решения почти всех текущих проблем Детройта». [75] Джон Могк, профессор права и эксперт по городскому планированию в юридической школе Университета Уэйна в Детройте, говорит:

Все думают, что именно беспорядки [1967 года] заставили белые семьи уехать. Некоторые люди уезжали в то время, но на самом деле именно после Милликена вы увидели массовое бегство в пригороды. Если бы дело пошло по-другому, вполне вероятно, что Детройт не испытал бы резкого снижения налоговой базы, которое произошло с тех пор. [75]

В ноябре 1973 года город избрал Коулмена Янга своим первым чернокожим мэром. После вступления в должность Янг подчеркнул необходимость увеличения расового разнообразия в полицейском департаменте, который был преимущественно белым. [76] Янг также работал над улучшением транспортной системы Детройта, но напряженность между Янгом и его коллегами из пригородов по региональным вопросам была проблематичной на протяжении всего срока его полномочий мэра.

В 1976 году федеральное правительство предложило 600 миллионов долларов (~2,5 миллиарда долларов в 2023 году) на строительство региональной системы скоростного транспорта под единым региональным управлением. [77] Однако неспособность Детройта и его пригородных соседей разрешить конфликты по поводу планирования транзита привела к тому, что регион потерял большую часть финансирования скоростного транспорта. [ необходима ссылка ] Затем город приступил к строительству надземной части системы циркулярного транспорта в центре города, которая стала известна как Detroit People Mover . [78]

Бензиновые кризисы 1973 и 1979 годов повлияли на автомобильную промышленность. Покупатели выбирали более компактные и экономичные автомобили, произведенные иностранными производителями, поскольку цены на бензин росли. Усилия по возрождению города были сведены на нет борьбой автомобильной промышленности, поскольку их продажи и доля на рынке снизились. Автопроизводители уволили тысячи сотрудников и закрыли заводы в городе, что еще больше подорвало налоговую базу. Чтобы противостоять этому, город использовал право принудительного отчуждения собственности для строительства двух новых крупных заводов по сборке автомобилей в городе. [79]

Янг стремился возродить город, стремясь увеличить инвестиции в приходящий в упадок центр города. Renaissance Center , многофункциональный офисный и торговый комплекс, открылся в 1977 году. Эта группа небоскребов была попыткой сохранить бизнес в центре города. [44] [80] [81] Янг также оказал городскую поддержку другим крупным застройкам, чтобы привлечь обратно в город жителей среднего и высшего класса. Несмотря на Renaissance Center и другие проекты, центр города продолжал терять бизнес в пользу зависимых от автомобилей пригородов. Крупные магазины и отели закрылись, а многие крупные офисные здания пустовали. Янга критиковали за то, что он слишком сосредоточился на развитии центра города и не сделал достаточно для снижения высокого уровня преступности в городе и улучшения городских услуг для жителей. [ необходима цитата ]

Высокий уровень безработицы усугублялся бегством среднего класса в пригороды, а некоторые жители покидали штат в поисках работы. Результатом для города стали более высокая доля бедных в его населении, сокращение налоговой базы, снижение стоимости недвижимости, заброшенные здания, заброшенные кварталы и высокий уровень преступности. [82]

16 августа 1987 года рейс 255 авиакомпании Northwest Airlines потерпел крушение недалеко от аэропорта Детройт Метро, в результате чего погибли все, кроме одного из 155 человек на борту, а также два человека на земле. [83]

В 1993 году Янг ушел в отставку с поста мэра Детройта, занимавшего этот пост дольше всех, решив не баллотироваться на шестой срок, а его преемником стал Деннис Арчер . Арчер отдал приоритет развитию центра города, смягчив напряженность с соседями из пригородов. Референдум о разрешении азартных игр в казино в городе прошел в 1996 году; несколько временных казино открылись в 1999 году, а постоянные казино в центре города с отелями открылись в 2007–2008 годах. [84]

Campus Martius , перепланировка главного перекрестка в центре города в новый парк, был открыт в 2004 году. Парк был назван одним из лучших общественных пространств в Соединенных Штатах. [85] [86] [87] В 2001 году первая часть реконструкции International Riverfront была завершена в рамках празднования 300-летия города. [88]

В сентябре 2008 года мэр Кваме Килпатрик (прослуживший шесть лет) ушел в отставку после осуждения за тяжкие преступления. В 2013 году Килпатрик был осужден по 24 федеральным пунктам обвинения в тяжких преступлениях, включая почтовое мошенничество , мошенничество с использованием электронных средств связи и рэкет [89] и был приговорен к 28 годам лишения свободы в федеральной тюрьме [90] . Деятельность бывшего мэра обошлась городу примерно в 20 миллионов долларов. [91] Примерно половина владельцев 305 000 объектов недвижимости Детройта не оплатили свои налоговые счета за 2011 год, в результате чего около 246 миллионов долларов (~329 миллионов долларов в 2023 году) налогов и сборов остались неуплаченными, почти половина из которых была причиталась Детройту. Остальные деньги должны были быть направлены округу Уэйн, государственным школам Детройта и библиотечной системе. [92]

Финансовый кризис города привел к тому, что Мичиган взял на себя административный контроль над его правительством. [93] Губернатор Рик Снайдер объявил чрезвычайное финансовое положение в марте 2013 года, заявив, что у города дефицит бюджета составляет 327 миллионов долларов, а долгосрочный долг составляет более 14 миллиардов долларов. Город справлялся с концами ежемесячно с помощью денег от облигаций, хранящихся на государственном эскроу-счете, и ввел обязательные неоплачиваемые выходные для многих городских работников. Эти проблемы, наряду с недофинансированием городских служб, таких как полиция и пожарные, и неэффективными планами по исправлению ситуации от мэра Бинга и городского совета [94], привели к тому, что штат Мичиган назначил управляющего по чрезвычайным ситуациям в Детройте. 14 июня 2013 года Детройт объявил дефолт по долгу в размере 2,5 млрд долларов, удержав выплату процентов в размере 39,7 млн долларов, в то время как управляющий по чрезвычайным ситуациям Кевин Орр встретился с держателями облигаций и другими кредиторами в попытке реструктурировать долг города в размере 18,5 млрд долларов и избежать банкротства. [95] 18 июля 2013 года Детройт стал крупнейшим городом США, подавшим заявление о банкротстве . [96] 3 декабря окружной суд США объявил его банкротом с долгом в размере 18,5 млрд долларов. [97] 7 ноября 2014 года был одобрен план города по выходу из банкротства. 11 декабря город официально вышел из банкротства. План позволил городу ликвидировать долг в размере 7 млрд долларов и инвестировать 1,7 млрд долларов в улучшение городских услуг. [98]

Одним из способов, которым город получил эти деньги, был Детройтский институт искусств (DIA). Имея более 60 000 произведений искусства стоимостью в миллиарды долларов, некоторые видели в этом ключ к финансированию этих инвестиций. Город придумал план монетизации искусства и его продажи, что привело к тому, что DIA стал частной организацией. После месяцев юридических баталий город наконец получил сотни миллионов долларов на финансирование нового Детройта. [99]

Одной из крупнейших попыток после банкротства улучшить городские услуги стало исправление сломанной системы уличного освещения города. В какой-то момент было подсчитано, что 40% фонарей не работали, что привело к проблемам общественной безопасности и отказу от жилья. План предусматривал замену устаревших натриевых ламп высокого давления на 65 000 светодиодных ламп. Строительство началось в конце 2014 года и закончилось в декабре 2016 года; Детройт является крупнейшим городом США с полностью светодиодным уличным освещением. [100]

В 2010-х годах граждане Детройта и новые жители предприняли несколько инициатив по улучшению городского пейзажа путем обновления и оживления районов. Такие проекты включают в себя волонтерские группы по обновлению [101] и различные движения городского садоводства . [102] За последние годы были завершены мили связанных с ними парков и ландшафтных работ. В 2011 году открылся пассажирский терминал Port Authority с речной набережной, соединяющей Hart Plaza с Renaissance Center. [81]

Один из символов многолетнего упадка города, Центральный вокзал Мичигана , долгое время пустовал. Город отремонтировал его, установив новые окна, лифты и удобства, завершив работы в декабре 2015 года. [104] В 2018 году Ford Motor Company выкупила здание и планирует использовать его для тестирования мобильности с потенциальным возвращением движения поездов. [105] Несколько других знаковых зданий были отремонтированы в частном порядке и приспособлены под кондоминиумы , отели, офисы или для культурных целей. Детройт упоминался как город возрождения, который изменил многие тенденции предыдущих десятилетий. [106] [107]

В городе наблюдается рост джентрификации . [108] Например, в центре города строительство Little Caesars Arena принесло с собой высококлассные магазины и рестораны вдоль Вудворд-авеню. Строительство офисных башен и кондоминиумов привело к притоку богатых семей, но также и к перемещению старожилов и культуры. [109] [110] Районы за пределами центра города и другие недавно возрожденные районы имеют средний доход домохозяйства примерно на 25% меньше, чем в джентрифицированных районах, и этот разрыв продолжает расти. [111] Арендная плата и стоимость жизни в этих джентрифицированных районах растут с каждым годом, вытесняя меньшинства и бедных, вызывая все большее расовое неравенство и разделение в городе. В 2019 году стоимость однокомнатного лофта в Ривертауне достигла 300 000 долларов США (~ 352 668 долларов США в 2023 году), при этом изменение цены продажи за пять лет составило более 500%, а средний доход вырос на 18%. [112] [ нужен лучший источник ]

.jpg/440px-Metro_Detroit_by_Sentinel-2,_2021-09-06_(big_version).jpg)

Детройт является центром городской зоны, состоящей из трёх округов (с населением 3 734 090 человек на площади 1 337 квадратных миль (3 460 км 2 ) по данным переписи населения США 2010 года ), шести округов столичной статистической зоны (население 5 322 219 человек на площади 3 913 квадратных миль [10 130 км 2 ] по данным переписи населения 2010 года) и девяти округов объединённой статистической зоны (население 5,3 миллиона человек на площади 5 814 квадратных миль [15 060 км 2 ] по данным 2010 года [update]). [113] [114] [115]

По данным Бюро переписи населения США , город имеет общую площадь 142,87 квадратных миль (370,03 км 2 ), из которых 138,75 квадратных миль (359,36 км 2 ) — это суша и 4,12 квадратных миль (10,67 км 2 ) — вода. [116] Детройт — главный город в Метро Детройт и Юго-Восточном Мичигане . Он расположен на Среднем Западе США и в районе Великих озер . [117]

Международный заповедник дикой природы Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge — единственный международный заповедник дикой природы в Северной Америке, уникально расположенный в самом сердце крупного мегаполиса. Заповедник включает острова, прибрежные водно-болотные угодья, болота, отмели и прибрежные земли вдоль 48 миль (77 км) реки Детройт и западной береговой линии озера Эри. [118]

Город плавно спускается с северо-запада на юго-восток по равнине, состоящей в основном из ледниковой и озерной глины. Наиболее заметной топографической особенностью города является Детройтская морена, широкий глиняный хребет, на котором расположены старые части Детройта и Виндзора, возвышающийся примерно на 62 фута (19 м) над рекой в своей самой высокой точке. [119] Самая высокая точка города находится прямо к северу от Gorham Playground на северо-западной стороне примерно в трех кварталах к югу от 8 Mile Road , на высоте от 675 до 680 футов (от 206 до 207 м). [120] Самая низкая точка Детройта находится вдоль реки Детройт, на высоте поверхности 572 фута (174 м). [121]

Belle Isle Park — это островной парк площадью 982 акра (1,534 кв. мили; 397 га) на реке Детройт, между Детройтом и Виндзором, Онтарио . Он соединен с материком мостом Макартура . Belle Isle Park содержит такие достопримечательности, как Мемориальный фонтан Джеймса Скотта , Консерватория Belle Isle , Детройтский яхт-клуб на соседнем острове, пляж длиной в полмили (800 м), поле для гольфа, природный центр, памятники и сады. С Sunset Point острова можно увидеть как горизонты Детройта, так и Виндзора. [122]

Три дорожные системы пересекают город: оригинальный французский шаблон с проспектами, расходящимися от набережной, и настоящие дороги с севера на юг, основанные на системе тауншипов Северо-Западного Ординанса . Город находится к северу от Виндзора, Онтарио. Детройт — единственный крупный город вдоль границы Канады и США, в котором нужно ехать на юг, чтобы пересечь границу с Канадой. [123]

В Детройте есть четыре пограничных перехода: мост Амбассадор и туннель Детройт-Виндзор обеспечивают проезд автотранспорта, а железнодорожный туннель Мичиган-Сентрал обеспечивает железнодорожный доступ в Канаду и из нее. Четвертый пограничный переход — паром для грузовиков Детройт-Виндзор , расположенный недалеко от соляной шахты Виндзор и острова Цуг . Рядом с островом Цуг юго-западная часть города была застроена соляной шахтой площадью 1500 акров (610 га), которая находится на глубине 1100 футов (340 м) под поверхностью. Соляная шахта Детройта , которой управляет Detroit Salt Company, имеет более 100 миль (160 км) дорог внутри. [124] [125]

.jpg/440px-One_Detroit_Center_(Detroit,_MI,_USA).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Skyline_of_Detroit,_Michigan_from_S_2014-12-07_(cropped,_Financial_District).jpg)

На панорамном виде набережная Детройта демонстрирует разнообразие архитектурных стилей. Постмодернистские неоготические шпили Ally Detroit Center были спроектированы так, чтобы отсылать к городским небоскребам в стиле ар-деко . Вместе с Renaissance Center эти здания образуют отличительный и узнаваемый горизонт. Примерами стиля ар-деко являются Guardian Building и Penobscot Building в центре города, а также Fisher Building и Cadillac Place в районе New Center недалеко от Wayne State University . Среди выдающихся сооружений города — крупнейший в США театр Fox Theatre , Detroit Opera House и Detroit Institute of Arts , все построенные в начале 20-го века. [126] [127]

В то время как в районах Downtown и New Center находятся высотные здания, большая часть окружающего города состоит из малоэтажных сооружений и односемейных домов. За пределами центра города жилые высотки находятся в районах с высоким классом, таких как East Riverfront, простирающийся до Grosse Pointe , и районе Palmer Park к западу от Woodward. Район University Commons-Palmer Park на северо-западе Детройта, недалеко от University of Detroit Mercy и Marygrove College , объединяет исторические районы, включая Palmer Woods , Sherwood Forest и University District . [ требуется ссылка ]

Сорок два значительных сооружения или объекта перечислены в Национальном реестре исторических мест . Районы, построенные до Второй мировой войны, демонстрируют архитектуру того времени, с деревянными каркасными и кирпичными домами в рабочих районах, большими кирпичными домами в районах среднего класса и богато украшенными особняками в районах высшего класса, таких как Браш-парк , Вудбридж , Индиан-Виллидж , Палмер-Вудс, Бостон-Эдисон и другие. [ требуется ссылка ]

Некоторые из старейших районов находятся вдоль основных коридоров Вудворд и Ист-Джефферсон , которые сформировали хребет города. Некоторые более новые жилые постройки также можно найти вдоль коридора Вудворд и на крайнем западе и северо-востоке. Самые старые сохранившиеся районы включают Уэст-Кэнфилд и Браш-Парк . Здесь были проведены многомиллионные реставрации существующих домов и строительство новых домов и кондоминиумов. [80] [128]

В городе находится одна из крупнейших в США сохранившихся коллекций зданий конца 19-го и начала 20-го века. [127] Архитектурно значимые церкви и соборы города включают церковь Святого Иосифа , старую церковь Святой Марии , церковь Сладчайшего Сердца Марии и собор Святейшего Таинства . [126]

Город ведет активную деятельность в области городского дизайна, сохранения исторических объектов и архитектуры. [129] Ряд проектов реконструкции центра города, из которых парк Campus Martius является одним из самых заметных, оживили части города. Парк Grand Circus и исторический район находятся недалеко от театрального района города ; Ford Field , домашний стадион Detroit Lions , и Comerica Park , домашний стадион Detroit Tigers . [126] Little Caesars Arena , новый дом для Detroit Red Wings и Detroit Pistons , с прилегающими жилыми, гостиничными и торговыми помещениями, открылся в 2017 году. [130] Планы проекта предусматривают строительство многофункционального жилья в кварталах, окружающих арену, и реконструкцию пустующего 14-этажного отеля Eddystone . Он станет частью The District Detroit, группы мест, принадлежащих Olympia Entertainment Inc. , включая Comerica Park и Detroit Opera House , среди прочих. [ необходима ссылка ]

Детройтский международный речной променад включает частично завершенный променад длиной в три с половиной мили с парками, жилыми зданиями и коммерческими зонами. Он простирается от Hart Plaza до моста Макартура, который соединяется с парком Belle Isle , крупнейшим островным парком в городе США. Речной променад включает государственный парк Tri-Centennial и гавань, первый городской государственный парк Мичигана. Вторая фаза — это расширение на две мили (3,2 км) от Hart Plaza до моста Ambassador , в общей сложности пять миль (8,0 км) парковой дороги от моста до моста. Городские планировщики предполагают, что пешеходные парки будут стимулировать жилую реконструкцию прибрежных объектов, отчужденных в соответствии с правом принудительного отчуждения . [131]

Другие крупные парки включают Ривер Руж (на юго-западной стороне), самый большой парк в Детройте; Палмер (к северу от Хайленд-парка ) и Чен-парк (на восточной стороне реки в центре города). [132]

В Детройте есть множество типов районов. Возрожденные центр города, Мидтаун , Корктаун, Нью- центр имеют много исторических зданий и высокую плотность, в то время как дальше, особенно на северо-востоке и на окраинах, [133] высокий уровень вакантных площадей является проблемой, для которой был предложен ряд решений. В 2007 году центр города Детройт был признан редакторами CNNMoney лучшим городским районом для выхода на пенсию среди крупнейших метрополий США . [134]

Lafayette Park — это возрождённый район на восточной стороне города , часть жилого района Людвига Миса ван дер Роэ . [135] 78-акровый (32 га) проект изначально назывался Gratiot Park. Спланированный Мисом ван дер Роэ , Людвигом Хильберсаймером и Альфредом Колдуэллом, он включает в себя благоустроенный парк площадью 19 акров (7,7 га) без сквозного движения, в котором расположены эти и другие малоэтажные жилые дома. [135] Иммигранты внесли свой вклад в возрождение городских районов, особенно на юго-западе Детройта. [136] Юго-западный Детройт в последние годы пережил процветающую экономику, о чём свидетельствует новое жилье, увеличение числа открытых предприятий и недавно открывшийся Mexicantown International Welcome Center. [137]

В городе есть многочисленные кварталы, состоящие из пустующих домов, что приводит к низкой плотности населения в этих районах, растягивая городские службы и инфраструктуру. Эти кварталы сосредоточены на северо-востоке и на окраинах города. [133] Обследование участков 2009 года показало, что около четверти жилых участков в городе не застроены или пустуют, а около 10% жилья города не заселены. [133] [138] [139] Обследование также показало, что большинство (86%) домов города находятся в хорошем состоянии, а меньшинство (9%) — в удовлетворительном состоянии, требующем лишь незначительного ремонта. [138] [139] [140] [141]

.jpg/440px-New_Amsterdam_Lofts_(4634813321).jpg)

Чтобы решить проблему вакансий, город начал сносить заброшенные дома, снеся 3000 из 10 000 в 2010 году, [142] но в результате низкая плотность создает нагрузку на инфраструктуру города. Чтобы исправить это, был предложен ряд решений, включая переселение жителей из менее населенных районов и преобразование неиспользуемого пространства в городское сельскохозяйственное использование, включая Hantz Woodlands , хотя город ожидает, что это будет находиться на стадии планирования еще до двух лет. [143] [144]

Государственное финансирование и частные инвестиции были сделаны с обещаниями восстановить кварталы. В апреле 2008 года город объявил о плане стимулирования на сумму 300 миллионов долларов (~417 миллионов долларов в 2023 году) для создания рабочих мест и возрождения кварталов, финансируемом за счет городских облигаций и оплачиваемом за счет ассигнований около 15% от налога на ставки. [143] Рабочие планы города по возрождению кварталов включают 7-Mile/Livernois, Brightmoor , East English Village, Grand River/Greenfield, North End и Osborn . [143] Частные организации пообещали существенное финансирование усилий. [145] [146] Кроме того, город очистил участок земли площадью 1200 акров (490 га) для крупномасштабного строительства квартала, который город называет Far Eastside Plan . [147] В 2011 году мэр Дэйв Бинг объявил о плане категоризации районов по их потребностям и определения приоритетности наиболее необходимых услуг для этих районов. [148]

Detroit Parks & Recreation обслуживает 308 общественных парков общей площадью 4950 (2003 га) акров или около 5,6% площади города. Belle Isle Park , крупнейший и наиболее посещаемый парк Детройта, является крупнейшим городским островным парком в США, занимая площадь 982 акра (397 га).

Детройт и остальная часть юго-восточного Мичигана имеют жаркий летний влажный континентальный климат ( Кеппен : Dfa ), на который, как и на другие места в штате, влияют Великие озера ; [149] [150] [151] город и близлежащие пригороды входят в зону морозостойкости USDA 6b, в то время как более отдаленные северные и западные пригороды, как правило, включены в зону 6a. [152] Зимы холодные, с умеренными снегопадами и температурой, не поднимающейся выше нуля в среднем 44 дня в году, при этом опускающейся до или ниже 0 °F (−18 °C) в среднем 4,4 дня в году; лето теплое или жаркое, с температурой, превышающей 90 °F (32 °C) в течение 12 дней. [153] Теплый сезон длится с мая по сентябрь. Среднемесячная дневная температура колеблется от 25,6 °F (−3,6 °C) в январе до 73,6 °F (23,1 °C) в июле. Официальные экстремальные температуры колеблются от 105 °F (41 °C) 24 июля 1934 года до −21 °F (−29 °C) 21 января 1984 года; рекордно низкий максимум составляет −4 °F (−20 °C) 19 января 1994 года , в то время как, наоборот, рекордно высокий минимум составляет 80 °F (27 °C) 1 августа 2006 года, самое последнее из пяти случаев. [153] Между показаниями 100 °F (38 °C) или выше, которые в последний раз наблюдались 17 июля 2012 года , может пройти десятилетие или два . Среднее окно для отрицательных температур приходится на период с 20 октября по 22 апреля, что обеспечивает вегетационный период продолжительностью 180 дней. [153]

Осадки умеренные и довольно равномерно распределены в течение года, хотя в более теплые месяцы, такие как май и июнь, в среднем выпадает больше, составляя в среднем 33,5 дюйма (850 мм) в год, но исторически колеблясь от 20,49 дюйма (520 мм) в 1963 году до 47,70 дюйма (1212 мм) в 2011 году. [153] Снегопад, который обычно выпадает в измеримых количествах в период с 15 ноября по 4 апреля (иногда в октябре и очень редко в мае), [153] в среднем составляет 42,5 дюйма (108 см) за сезон, хотя исторически колеблется от 11,5 дюйма (29 см) в 1881–82 годах до 94,9 дюйма (241 см) в 2013–14 годах . [153] Толстый снежный покров нечасто можно увидеть, в среднем только 27,5 дней с 3 дюймами (7,6 см) или более снежного покрова. [153] Грозы часты в районе Детройта. Обычно они случаются весной и летом. [154]

Просмотр и редактирование необработанных графических данных.

По данным переписи населения США 2020 года , в городе проживало 639 111 человек, что ставит его на 27-е место по численности населения в США. [161] [162] Из всех крупных городов США, сокращающихся в численности населения, в Детройте наблюдалось самое резкое сокращение населения за последние 70 лет (на 1 210 457 человек) и второе по величине процентное сокращение (на 65,4%). Хотя сокращение населения Детройта продолжалось с 1950 года, самым резким периодом стало значительное сокращение на 25% между переписью 2000 и 2010 годов. [162]

639 111 жителей Детройта представляют 269 445 домохозяйств и 162 924 семьи, проживающие в городе. Плотность населения составляла 5 144,3 человек на квадратную милю (1 986,2 человек/км 2 ). Было 349 170 единиц жилья при средней плотности 2 516,5 единиц на квадратную милю (971,6 единиц/км 2 ). Из 269 445 домохозяйств, 34,4% имели детей в возрасте до 18 лет, проживающих с ними, 21,5% были супружескими парами, живущими вместе, 31,4% имели женщину-домохозяйку без мужей, 39,5% не имели семей, 34,0% состояли из отдельных лиц, и 3,9% имели кого-то, живущего в одиночестве в возрасте 65 лет и старше. Средний размер домохозяйства составил 2,59 человека, а средний размер семьи — 3,36 человека.

В городе наблюдалось широкое распределение по возрасту: 31,1% были моложе 18 лет, 9,7% — от 18 до 24 лет, 29,5% — от 25 до 44 лет, 19,3% — от 45 до 64 лет и 10,4% — в возрасте 65 лет и старше. Средний возраст составил 31 год. На каждые 100 женщин приходилось 89,1 мужчин. На каждые 100 женщин в возрасте 18 лет и старше приходилось 83,5 мужчин.

Согласно исследованию 2014 года, 67% населения города идентифицируют себя как христиане , 49% исповедуют протестантские церкви, а 16% исповедуют римско-католическую веру, [163] [164] в то время как 24% не заявляют о своей религиозной принадлежности . Другие религии в совокупности составляют около 8% населения.

Потеря рабочих мест в промышленности и рабочем классе в городе привела к высокому уровню бедности и связанным с этим проблемам. [165] С 2000 по 2009 год предполагаемый средний доход домохозяйства в городе упал с 29 526 до 26 098 долларов. [166] По состоянию на 2010 год [update]средний доход Детройта был ниже среднего по США на несколько тысяч долларов. Из каждых трех жителей Детройта один живет в бедности. Люк Бергманн, автор книги Getting Ghost: Two Young Lives and the Struggle for the Soul of an American City , сказал в 2010 году: «Детройт теперь один из самых бедных крупных городов в стране». [167]

В Американском общественном опросе 2018 года медианный доход домохозяйства в городе составил 31 283 доллара, по сравнению со медианным показателем для Мичигана в 56 697 долларов. [168] Медианный доход семьи составил 36 842 доллара, что значительно ниже медианного показателя по штату в 72 036 долларов. [169] 33,4% семей имели доход на уровне или ниже федерально определенного уровня бедности. Из общей численности населения 47,3% лиц моложе 18 лет и 21,0% лиц в возрасте 65 лет и старше имели доход на уровне или ниже федерально определенного уровня бедности. [170]

Начиная с подъема автомобильной промышленности, население Детройта увеличилось более чем в шесть раз в течение первой половины 20-го века, поскольку приток европейских, ближневосточных ( ливанских , ассирийских/халдейских ) и южных мигрантов привезли свои семьи в город. [178] С этим экономическим бумом после Первой мировой войны афроамериканское население выросло с всего лишь 6000 в 1910 году [179] до более чем 120 000 к 1930 году. [180] Возможно, один из самых явных примеров дискриминации по соседству произошел в 1925 году, когда афроамериканский врач Оссиан Свит обнаружил свой дом окруженным разъяренной толпой его враждебных белых соседей, яростно протестовавших против его нового переезда в традиционно белый район. Свит и десять членов его семьи и друзей были преданы суду за убийство, поскольку один из членов толпы, бросавших камни в недавно купленный дом, был застрелен кем-то, стрелявшим из окна второго этажа. [181]

Detroit has a relatively large Mexican-American population. In the early 20th century, thousands of Mexicans came to Detroit to work in agricultural, automotive, and steel jobs. During the Mexican Repatriation of the 1930s many Mexicans in Detroit were willingly repatriated or forced to repatriate. By the 1940s much of the Mexican community began to settle what is now Mexicantown.[182] Immigration from Jalisco significantly increased the Latino population in the 1990s. By 2010 Detroit had 48,679 Hispanics, including 36,452 Mexicans: a 70% increase from 1990.[183]

After World War II, many people from Appalachia also settled in Detroit. Appalachians formed communities and their children acquired southern accents.[184] Many Lithuanians also settled in Detroit during the World War II era, especially on the city's Southwest side in the West Vernor area,[185] where the renovated Lithuanian Hall reopened in 2006.[186][187]

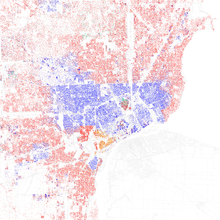

While African Americans previously[when?] comprised only 13% of Michigan's population, by 2010 they made up nearly 82% of Detroit's population. The next largest population groups were white people, at 10%, and Hispanics, at 6%.[188] In 2001, 103,000 Jews, or about 1.9% of the population, were living in the Detroit area.[189] According to the 2010 census, segregation in Detroit has decreased in absolute and relative terms and in the first decade of the 21st century, about two-thirds of the total black population in the metropolitan area resided within the city limits of Detroit.[190][191] The number of integrated neighborhoods increased from 100 in 2000 to 204 in 2010. Detroit also moved down the ranking from number one most segregated city to number four.[192] A 2011 op-ed in The New York Times attributed the decreased segregation rating to the overall exodus from the city, cautioning that these areas may soon become more segregated.

As of 2002, Detroit's percentage of Asians was 1%.[193] There are four areas in Detroit with significant Asian and Asian American populations. Northeast Detroit has a large population of Hmong[194] with a smaller group of Lao people. A portion of Detroit next to eastern Hamtramck includes Bangladeshi Americans, Indian Americans, and Pakistani Americans; nearly all of the Bangladeshi population in Detroit lives in that area. The area north of downtown has transient Asian national origin residents who are university students or hospital workers. Few of them have permanent residency after schooling ends. They are mostly Chinese and Indian but the population also includes Filipinos, Koreans, and Pakistanis. In Southwest Detroit and western Detroit there are smaller, scattered Asian communities.[193][195]

Several major corporations are based in the city, including three Fortune 500 companies. The most heavily represented sectors are manufacturing (particularly automotive), finance, technology, and health care. The most significant companies based in Detroit include General Motors, Rocket Mortgage, Ally Financial, Compuware, Shinola, American Axle, Little Caesars, DTE Energy, Lowe Campbell Ewald, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, and Rossetti Architects.

About 80,500 people work in downtown Detroit, comprising one-fifth of the city's employment base.[197][198] Aside from the numerous Detroit-based companies listed above, downtown contains large offices for Comerica, Chrysler, Fifth Third Bank, HP Enterprise, Deloitte, PricewaterhouseCoopers, KPMG, and Ernst & Young. Ford Motor Company is in the adjacent city of Dearborn.[199]

Thousands more employees work in Midtown, north of the central business district. Midtown's anchors are the city's largest single employer Detroit Medical Center, Wayne State University, and the Henry Ford Health System in New Center. Midtown is also home to watchmaker Shinola and an array of small and startup companies. New Center bases TechTown, a research and business incubator hub that is part of the Wayne State University system.[200] Like downtown, Corktown Is experiencing growth with the new Ford Corktown Campus under development.[201][202]

Many downtown employers are relatively new, as there has been a marked trend of companies moving from satellite suburbs into the downtown core.[203] Compuware completed its world headquarters in downtown in 2003. OnStar, Blue Cross Blue Shield, and HP Enterprise Services are at the Renaissance Center. PricewaterhouseCoopers Plaza offices are adjacent to Ford Field, and Ernst & Young completed its office building at One Kennedy Square in 2006. Perhaps most prominently, in 2010, Quicken Loans, one of the largest mortgage lenders, relocated its world headquarters and 4,000 employees to downtown Detroit, consolidating its suburban offices.[204] In July 2012, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office opened its Elijah J. McCoy Satellite Office in the Rivertown/Warehouse District as its first location outside Washington, D.C.'s metropolitan area.[205]

In April 2014, the United States Department of Labor reported the city's unemployment rate at 14.5%.[206]

The city of Detroit and other public–private partnerships have attempted to catalyze the region's growth by facilitating the building and historical rehabilitation of residential high-rises in the downtown, creating a zone that offers many business tax incentives, creating recreational spaces such as the Detroit RiverWalk, Campus Martius Park, Dequindre Cut Greenway, and Green Alleys in Midtown. The city has cleared sections of land while retaining some historically significant vacant buildings in order to spur redevelopment;[207] even though it has struggled with finances, the city issued bonds in 2008 to provide funding for ongoing work to demolish blighted properties.[143] Two years earlier, downtown reported $1.3 billion in restorations and new developments which increased the number of construction jobs in the city.[80] In the decade prior to 2006, downtown gained more than $15 billion in new investment from private and public sectors.[208]

Despite the city's recent financial issues, many developers remain unfazed by Detroit's problems.[209] Midtown is one of the most successful areas within Detroit to have a residential occupancy rate of 96%.[210] Numerous developments have been recently completed or are in various stages of construction. These include the $82 million reconstruction of downtown's David Whitney Building (now an Aloft Hotel and luxury residences), the Woodward Garden Block Development in Midtown, the residential conversion of the David Broderick Tower in downtown, the rehabilitation of the Book Cadillac Hotel (now a Westin and luxury condos) and Fort Shelby Hotel (now Doubletree) also in downtown, and various smaller projects.[211][80]

Downtown's population of young professionals is growing, and retail is expanding.[212][213] A study in 2007 found out that Downtown's new residents are predominantly young professionals (57% are ages 25 to 34, 45% have bachelor's degrees, and 34% have a master's or professional degree),[197][212][214] a trend which has hastened over the last decade. Since 2006, $9 billion has been invested in downtown and surrounding neighborhoods; $5.2 billion of which has come in 2013 and 2014.[215] Construction activity, particularly rehabilitation of historic downtown buildings, has increased markedly. As of 2014, the number of vacant downtown buildings has dropped from nearly 50 to around 13.[216]

In 2013 Meijer, a midwestern retail chain, opened its first supercenter store in Detroit;[217] this was a $20 million, 190,000-square-foot store in the northern portion of the city and it also is the centerpiece of a new $72 million shopping center named Gateway Marketplace.[218] In 2015 Meijer opened its second supercenter store in the city.[219] In 2019 JPMorgan Chase announced plans to invest $50 million more in affordable housing, job training, and entrepreneurship by the end of 2022, growing its investment to $200 million.[220]

.jpg/440px-March_for_Science_IMG_20170422_145254_(41912894840).jpg)

.jpg/440px-View_from_upper_level_of_Ford_display_--_2018_North_American_International_Auto_Show_(40540943864).jpg)

In the central portions of Detroit, the population of young professionals, artists, and other transplants is growing and retail is expanding.[212] This dynamic is luring additional new residents, and former residents returning from other cities, to the city's Downtown along with the revitalized Midtown and New Center areas.[197][212][214]

A desire to be closer to the urban scene has attracted some young professionals to reside in inner ring suburbs such as Ferndale and Royal Oak.[221] The proximity to Windsor provides for views and nightlife, along with Ontario's minimum drinking age of 19.[222] A 2011 study by Walk Score recognized Detroit for its above average walkability among large U.S. cities.[223] About two-thirds of suburban residents occasionally dine and attend cultural events or take in professional games in the city.[224]

Known as the world's automotive center,[225] "Detroit" is a metonym for that industry.[226] It is an important source of popular music legacies celebrated by the city's two familiar nicknames, the Motor City and Motown.[227] Other nicknames arose in the 20th century, including City of Champions, beginning in the 1930s for its successes in individual and team sport;[228] The D; Hockeytown (a trademark owned by the Detroit Red Wings); Rock City (after the Kiss song "Detroit Rock City"); and The 313 (its telephone area code).[d][229]

Live music has been a prominent feature of Detroit's nightlife since the late 1940s, bringing the city recognition under the nickname "Motown".[230] The metropolitan area has many nationally prominent live music venues. Concerts hosted by Live Nation perform throughout the Detroit area. The theater venue circuit is the United States' second largest and hosts Broadway performances.[231][232]

The city has a rich musical heritage and has contributed to many genres over the decades.[229] Important music events include the Detroit International Jazz Festival, the Detroit Electronic Music Festival, the Motor City Music Conference (MC2), the Urban Organic Music Conference, the Concert of Colors, and the hip-hop Summer Jamz festival.[229]

In the 1940s, Detroit blues artist John Lee Hooker became a long-term resident in the Delray neighborhood. Hooker, among other important blues musicians, migrated from his home in Mississippi, bringing the Delta blues to Detroit. Hooker recorded for Fortune Records, the biggest pre-Motown blues/soul label. During the 1950s, the city became a center for jazz, with stars performing in the Black Bottom neighborhood.[44] Prominent emerging jazz musicians included trumpeter Donald Byrd (who attended Cass Tech and performed with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers early in his career) and saxophonist Pepper Adams (who enjoyed a solo career and accompanied Byrd on several albums). The Graystone International Jazz Museum documents jazz in Detroit.[233]

Other prominent Motor City R&B stars in the 1950s and early 1960s were Nolan Strong, Andre Williams, and Nathaniel Mayer—who all scored local and national hits on the Fortune Records label. According to Smokey Robinson, Strong was a primary influence on his voice as a teenager. The Fortune label, a family-operated label on Third Avenue, was owned by the husband-and-wife team of Jack Brown and Devora Brown. Fortune—which also released country, gospel and rockabilly LPs and 45s—laid the groundwork for Motown, which became Detroit's most legendary record label.[234]

Berry Gordy, Jr. founded Motown Records, which rose to prominence during the 1960s and early 1970s with acts such as Stevie Wonder, the Temptations, the Four Tops, Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, Diana Ross & the Supremes, the Jackson 5, Martha and the Vandellas, the Spinners, Gladys Knight & the Pips, the Marvelettes, the Elgins, the Monitors, the Velvelettes, and Marvin Gaye. Artists were backed by in-house vocalists[235] the Andantes and the Funk Brothers.

"The Motown sound" played an important role in the crossover appeal with popular music, since it was the first African American–owned record label to primarily feature African-American artists. Gordy moved Motown to Los Angeles in 1972 to pursue film production, but the company has since returned to Detroit. Aretha Franklin, another Detroit R&B star, carried the Motown sound; however, she did not record with Berry's Motown label.[229]

Local artists and bands rose to prominence in the 1960s and 70s, including the MC5, Glenn Frey, the Stooges, Bob Seger, Amboy Dukes featuring Ted Nugent, Mitch Ryder, and The Detroit Wheels, Rare Earth, Alice Cooper, and Suzi Quatro. The group Kiss emphasized the city's connection with rock in the song "Detroit Rock City" and the movie produced in 1999. In the 1980s, Detroit was an important center of the hardcore punk rock underground with many nationally known bands coming out of the city and its suburbs, such as the Necros, the Meatmen, and Negative Approach.[234]

In the 1990s and 2000s, the city produced many influential hip hop artists, including Eminem, the hip-hop artist with the highest cumulative sales, his rap group D12, hip-hop rapper and producer Royce da 5'9", hip-hop producer Denaun Porter, hip-hop producer J Dilla, rapper and musician Kid Rock and rappers Big Sean and Danny Brown. The band Sponge toured and produced music.[229][234] The city also has an active garage rock scene that has generated national attention with acts such as the White Stripes, the Von Bondies, the Detroit Cobras, the Dirtbombs, Electric Six, and the Hard Lessons.[229] Detroit is cited as the birthplace of techno music in the early 1980s.[236] The city also lends its name to an early and pioneering genre of electronic dance music, "Detroit techno". Featuring science fiction imagery and robotic themes, its futuristic style was greatly influenced by the geography of Detroit's urban decline and its industrial past.[44] Prominent Detroit techno artists include Juan Atkins, Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson, and Jeff Mills. The Detroit Electronic Music Festival, now known as Movement, occurs annually in late May on Memorial Day Weekend, and takes place in Hart Plaza.

.jpg/440px-Detroit_December_2019_14_(Fox_Theatre).jpg)

Major theaters in Detroit include the Fox Theatre (5,174 seats), Music Hall Center for the Performing Arts (1,770 seats), the Gem Theatre (451 seats), Masonic Temple Theatre (4,404 seats), the Detroit Opera House (2,765 seats), the Fisher Theatre (2,089 seats), The Fillmore Detroit (2,200 seats), Saint Andrew's Hall, the Majestic Theater, and Orchestra Hall (2,286 seats), which hosts the renowned Detroit Symphony Orchestra. The Nederlander Organization, the largest controller of Broadway productions in New York City, originated with the purchase of the Detroit Opera House in 1922 by the Nederlander family.[229]

Motown Motion Picture Studios with 535,000 square feet (49,700 m2) produces movies in Detroit and the surrounding area based at the Pontiac Centerpoint Business Campus for a film industry expected to employ over 4,000 people in the metro area.[237]

Detroit is home to the world's first destination marketing organization, the Detroit Metro Convention and Visitor's Bureau, also known as Visit Detroit.[238][239] Founded in 1896, the organization now operates at 211 West Fort Street as Visit Detroit. [240]

Because of its unique culture, distinctive architecture, and revitalization and urban renewal efforts in the 21st century, Detroit has enjoyed increased prominence as a tourist destination in recent years. The New York Times listed Detroit as the ninth-best destination in its list of 52 Places to Go in 2017,[241] while travel guide publisher Lonely Planet named Detroit the second-best city in the world to visit in 2018.[242]Time named Detroit as one of the 50 World's Greatest Places of 2022 to explore.[243]

Many of the area's prominent museums are in the historic cultural center neighborhood around Wayne State University and the College for Creative Studies. These museums include the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Detroit Historical Museum, Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, the Detroit Science Center, as well as the main branch of the Detroit Public Library. Other cultural highlights include Motown Historical Museum, the Ford Piquette Avenue Plant museum, the Pewabic Pottery studio and school, the Tuskegee Airmen Museum, Fort Wayne, the Dossin Great Lakes Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, the Contemporary Art Institute of Detroit, and the Belle Isle Conservatory.

In 2010, the G.R. N'Namdi Gallery opened in a 16,000-square-foot (1,500 m2) complex in Midtown. Important history of America and the Detroit area are exhibited at The Henry Ford in Dearborn, the United States' largest indoor-outdoor museum complex.[244] The Detroit Historical Society provides information about tours of area churches, skyscrapers, and mansions. Inside Detroit hosts tours, educational programming, and a downtown welcome center. Other sites of interest are the Detroit Zoo in Royal Oak, the Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, the Anna Scripps Whitcomb Conservatory on Belle Isle, and Walter P. Chrysler Museum in Auburn Hills.[126]

Greektown and three downtown casino resort hotels serve as part of an entertainment hub. The Eastern Market farmer's distribution center is the largest open-air flowerbed market in the United States and has more than 150 foods and specialty businesses.[245] On Saturdays, about 45,000 people shop there.[246] The annual Detroit Festival of the Arts in Midtown draws about 350,000 people.[247]

Annual summer events include the Electronic Music Festival, International Jazz Festival, the Woodward Dream Cruise, the African World Festival, the country music Hoedown, Noel Night, and Dally in the Alley. Within downtown, Campus Martius Park hosts large events, including the annual Motown Winter Blast. As the world's traditional automotive center, the city hosts the North American International Auto Show. Held since 1924, America's Thanksgiving Parade is one of the nation's largest.[248] River Days, a five-day summer festival on the International Riverfront lead up to the Windsor–Detroit International Freedom Festival fireworks, which draw super sized-crowds ranging from hundreds of thousands to over three million people.[224][229][249]

An important civic sculpture is The Spirit of Detroit by Marshall Fredericks at the Coleman Young Municipal Center. The image is often used as a symbol of Detroit, and the statue is occasionally dressed in sports jerseys to celebrate when a Detroit team is doing well.[250] A memorial to Joe Louis is located at the intersection of Jefferson and Woodward Avenues. The sculpture, commissioned by Sports Illustrated and executed by Robert Graham, is a 24-foot (7.3 m) long arm with a fisted hand suspended by a pyramidal framework.

Detroit is one of four U.S. cities that have venues within the city representing the four major sports in North America. Detroit is the only city to have its four major sports teams play within its downtown district.[251] Venues include: Comerica Park (home of MLB's Detroit Tigers), Ford Field (home of the NFL's Detroit Lions), and Little Caesars Arena (home of the NHL's Detroit Red Wings and the NBA's Detroit Pistons).

Detroit has won titles in all four of the major professional sports leagues. The Tigers have won four World Series titles (1935, 1945, 1968, and 1984). The Red Wings have won 11 Stanley Cups (1935–36, 1936–37, 1942–43, 1949–50, 1951–52, 1953–54, 1954–55, 1996–97, 1997–98, 2001–02, 2007–08) (the most by an American NHL franchise).[252] The Lions have won 4 NFL titles (1935, 1952, 1953, 1957). The Pistons have won three NBA titles (1989, 1990, 2004).[229] In the years following the mid-1930s, Detroit was referred to as the "City of Champions" after the Tigers, Lions, and Red Wings captured the three major professional sports championships in existence at the time in a seven-month period (the Tigers won the World Series in October 1935; the Lions won the NFL championship in December 1935; the Red Wings won the Stanley Cup in April 1936).[228]

Founded in 2012 as a semi-professional soccer club, Detroit City FC plays professional soccer in the USL Championship. Nicknamed, Le Rouge, the club are two-time champions of NISA since joining in 2020. They play their home matches in Keyworth Stadium, which is located in the enclave of Hamtramck.[253]

In college sports, Detroit's central location within the Mid-American Conference (MAC) has made it a frequent site for the league's championship events. While the MAC Basketball Tournament moved permanently to Cleveland starting in 2000, the MAC Football Championship Game has been played at Ford Field since 2004 and annually attracts 25,000 to 30,000 fans. The University of Detroit Mercy has an NCAA Division I program, and Wayne State University has both NCAA Division I and II programs. The NCAA football Quick Lane Bowl is held at Ford Field each December.

The city hosted the 2005 MLB All-Star Game, Super Bowl XL in 2006, the 2006 and 2012 World Series, WrestleMania 23 in 2007, and the NCAA Final Four in April 2009. The Detroit Indy Grand Prix is held in Belle Isle Park. In 2007, open-wheel racing returned to Belle Isle with both Indy Racing League and American Le Mans Series Racing.[254] From 1982 to 1988, Detroit held the Detroit Grand Prix, at the Detroit street circuit.

In 1932, Eddie "The Midnight Express" Tolan from Detroit won the 100- and 200-meter races and two gold medals at the 1932 Summer Olympics. Joe Louis won the heavyweight championship of the world in 1937. Detroit has made the most bids to host the Summer Olympics without ever being awarded the games, with seven unsuccessful bids for the 1944, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1964, 1968, and 1972 summer games.[229]

In 2024, Detroit hosted the NFL Draft. Over 775,000 people were present in downtown Detroit over the course of the three-day event, making it the highest attended draft on record. [255]

The city is governed pursuant to the home rule Charter of the City of Detroit. The government is run by a mayor, the nine-member Detroit City Council, the eleven-member Board of Police Commissioners, and a clerk. All of these officers are elected on a nonpartisan ballot, with the exception of four of the police commissioners, who are appointed by the mayor. Detroit has a "strong mayoral" system, with the mayor approving departmental appointments. The council approves budgets, but the mayor is not obligated to adhere to any earmarking. The city clerk supervises elections and is formally charged with the maintenance of municipal records. City ordinances and substantially large contracts must be approved by the council.[256][257] The Detroit City Code is the codification of Detroit's local ordinances.

Presently three Community Advisory Councils advise City Council representatives. Residents of each of Detroit's seven districts have the option of electing Community Advisory Councils.[258] The city clerk supervises elections and is formally charged with the maintenance of municipal records. Municipal elections for mayor, city council and city clerk are held at four-year intervals, in the year after presidential elections.[257] Following a November 2009 referendum, seven council members will be elected from districts beginning in 2013 while two will continue to be elected at-large.[259]

Detroit's courts are state-administered and elections are nonpartisan. The Probate Court for Wayne County is in the Coleman A. Young Municipal Center in downtown. The Circuit Court is across Gratiot Avenue in the Frank Murphy Hall of Justice. The city is home to the Thirty-Sixth District Court, as well as the First District of the Michigan Court of Appeals and the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan. The city provides law enforcement through the Detroit Police Department and emergency services through the Detroit Fire Department.[260][261]