Христианское учение о Троице ( лат . Trinitas , букв. «триада», от лат . trinus «тройной») [1] является центральным учением о природе Бога в большинстве христианских церквей, которое определяет единого Бога, существующего в трех, вечных, единосущных божественных лицах : [2] [3] Бог Отец , Бог Сын ( Иисус Христос ) и Бог Святой Дух , три различных лица ( ипостась ), разделяющие одну сущность/сущность/природу ( homousion ). [4]

Как заявил Четвертый Латеранский собор , Отец рождает, Сын рождается, а Святой Дух исходит. [5] [6] [7] В этом контексте одна сущность/природа определяет, что такое Бог, в то время как три лица определяют, кто такой Бог. [8] [9] Это одновременно выражает их различие и их неразрывное единство. Таким образом, весь процесс творения и благодати рассматривается как единое общее действие трех божественных лиц, в котором каждое лицо проявляет атрибуты, уникальные для него в Троице, тем самым доказывая, что все исходит «от Отца», «через Сына» и «в Святом Духе». [10]

Это учение называется тринитаризмом , а его приверженцы называются тринитариями , в то время как его противники называются антитринитариями или нетринитариями . Христианские нетринитарии включают унитаризм , бинитаризм и модализм .

Хотя разработанное учение о Троице не выражено явно в книгах , составляющих Новый Завет , Новый Завет обладает триадическим пониманием Бога [11] и содержит ряд тринитарных формул . [12] [13] Учение о Троице было впервые сформулировано среди ранних христиан (середина II века и позже) и отцов Церкви , когда они пытались понять отношения между Иисусом и Богом в своих библейских документах и предшествующих традициях. [14]

Ветхий Завет во многих местах трактовался как относящийся к Троице. Например, в повествовании о сотворении мира в Книге Бытия , в частности, местоимения первого лица множественного числа в Книге Бытия 1:26–27 и Книге Бытия 3:22 («Сотворим человека по образу Нашему [...] человек стал как один из Нас »).

«И сказал Бог: сотворим человека по образу Нашему и по подобию Нашему. И да владычествуют они над рыбами морскими, и над птицами небесными, и над скотом, и над всею землею, и над всеми гадами, пресмыкающимися по земле». [...] «И сказал Господь Бог: вот, Адам стал как один из Нас в познании добра и зла [...]»

— Бытие 1:26, 3:22 ESV

Традиционное христианское толкование этих местоимений заключается в том, что они относятся к множественности лиц в Божестве. Библейский комментатор Виктор П. Гамильтон излагает несколько толкований, включая наиболее распространенное среди библейских ученых, которое заключается в том, что местоимения не относятся к другим лицам в Божестве, а к «небесному суду» Исайи 6. Теологи Мередит Клайн [15] и Герхард фон Рад отстаивают эту точку зрения, как говорит фон Рад: «Необычное множественное число («Давайте») призвано помешать нам слишком прямо относить образ Бога к Богу Господу. Бог включает себя в число небесных существ своего двора и тем самым скрывает себя в этом большинстве». [16] Гамильтон отмечает, что это толкование предполагает, что Бытие 1 расходится с Исайей 40:13–14: Кто измерил Духа Господа, или какой человек показал Ему совет Его? С кем Он советовался, и кто дал Ему понять? Кто научил его пути справедливости, и научил его знанию, и показал ему путь понимания? То есть, если множественные местоимения Бытия 1 учат, что Бог советуется и творит с «небесным судом», то это противоречит утверждению в Исайе, что Бог не ищет совета ни у кого. По словам Гамильтона, наилучшая интерпретация «приближается к тринитарному пониманию, но использует менее прямую терминологию». [17] : 133 Следуя за DJA Clines , он утверждает, что множественное число раскрывает «двойственность внутри Божества», которая напоминает «Духа Божьего», упомянутого в стихе 2, И Дух Божий носился над поверхностью вод. Гамильтон также говорит, что неразумно предполагать, что автор Бытия был слишком теологически примитивен, чтобы иметь дело с такой концепцией, как «множественность внутри единства»; [17] : 134 Таким образом, Гамильтон выступает за структуру прогрессивного откровения , в которой учение о Троице сначала раскрывается неясно, а затем ясно в Новом Завете.

Еще одно из таких мест — пророчество о Мессии в Исаии 9. Мессия назван «Чудный, Советник, Бог крепкий, Отец вечности, Князь мира». Некоторые христиане видят в этом стихе, что Мессия будет представлять Троицу на земле. Это потому, что Советник — это титул Святого Духа (Иоанна 14:26), Троица — это Бог, Отец — это титул Бога Отца, а Князь мира — это титул Иисуса. Этот стих также используется для поддержки Божественности Христа . [18]

Другой стих, используемый для подтверждения Божественности Христа, — [19]

«Видел я в ночных видениях, и вот, с облаками небесными шел как бы Сын Человеческий, и дошел до Ветхого Днями , и предстал пред Ним. И дана была Ему власть, слава и царство, чтобы все народы, племена и языки служили Ему; владычество Его — владычество вечное, которое не прейдет, и царство Его не разрушится».

— Даниил 7:13–14 ESV

Это потому, что и Ветхий днями (Бог Отец), и Сын Человеческий (Иисус, Мф. 16:13) имеют вечное владычество, которое приписывается Богу в Псалме 144:13. [20]

Некоторые также утверждают,

«И пролил Господь на Содом и Гоморру дождем серу и огонь от Господа с неба».

— Бытие 19:24 ESV

быть тринитарным, проводя видимое различие между Господом на небесах и Господом на земле. [ необходима цитата ]

Люди также видят Троицу, когда Ветхий Завет ссылается на Слово Божье (Псалом 33:6), Его Дух (Исаия 61:1) и Мудрость (Притчи 9:1), а также на такие повествования, как явление трех мужей Аврааму . [ 21] Однако среди христианских ученых-тринитариев в целом существует согласие, что было бы выше намерения и духа Ветхого Завета, если бы они напрямую соотносили эти понятия с более поздней доктриной Триединства. [22]

Некоторые отцы Церкви считали, что знание тайны было даровано пророкам и святым Ветхого Завета, и что они отождествляли божественного посланника из Бытия 16:7, Бытия 21:17, Бытия 31:11, Исхода 3:2 и Мудрости премудрых книг с Сыном, а «дух Господень» — со Святым Духом. [22]

Другие отцы церкви, такие как Григорий Назианзин , утверждали в своих «Речах» , что откровение было постепенным, утверждая, что Отец был провозглашен в Ветхом Завете открыто, а Сын лишь неявно, потому что «было небезопасно, когда Божество Отца еще не было признано, открыто провозглашать Сына» [23] .

Бытие 18–19 интерпретируется христианами как тринитарный текст. В повествовании Господь является Аврааму, которого посетили три человека. [24] В Бытие 19 «два ангела» посещают Лота в Содоме. [25] Взаимодействие между Авраамом, с одной стороны, и Господом/тремя людьми/двумя ангелами, с другой, было интригующим текстом для тех, кто верил в единого Бога в трех лицах. Иустин Мученик и Жан Кальвин аналогичным образом интерпретировали его так, что Авраама посетил Бог, которого сопровождали два ангела. [26] Иустин предполагал, что Бог, посетивший Авраама, был отличен от Бога, который остается на небесах, но тем не менее был идентифицирован как (монотеистический) Бог. Иустин интерпретировал Бога, посетившего Авраама, как Иисуса, второе лицо Троицы. [ необходима цитата ]

Августин, напротив, считал, что три посетителя Авраама были тремя лицами Троицы. [26] Он не видел никаких указаний на то, что посетители были неравными, как это было бы в прочтении Иустина. Затем в Бытии 19 к двум посетителям Лот обратился в единственном числе: «Лот сказал им: „Нет, господин мой “ » (Быт. 19:18). [26] Августин видел, что Лот мог обращаться к ним как к одному, потому что они имели единую сущность, несмотря на множественность лиц. [a]

Христиане интерпретируют теофании , или явления Ангела Господня , как откровения личности, отличной от Бога, которая, тем не менее, называется Богом. Эта интерпретация встречается в христианстве уже у Иустина Мученика и Мелитона Сардийского и отражает идеи, которые уже присутствовали у Филона . [27] Таким образом, ветхозаветные теофании рассматривались как христофании , каждая из которых была «довоплощенным явлением Мессии». [28]

Хотя разработанное учение о Троице не выражено явно в книгах, составляющих Новый Завет , Новый Завет содержит несколько тринитарных формул , включая Матфея 28:19, 2 Коринфянам 13:14, Ефесянам 4:4–6, 1 Петра 1:2 и Откровение 1:4–6. [12] [29] Размышления ранних христиан над такими отрывками, как Великое поручение : «Итак идите, научите все народы, крестя их во имя Отца и Сына и Святого Духа» и благословение апостола Павла : «Благодать Господа Иисуса Христа и любовь Бога Отца и общение Святого Духа со всеми вами», побуждая богословов на протяжении всей истории пытаться сформулировать отношения между Отцом, Сыном и Святым Духом.

В конце концов, разнообразные ссылки на Бога, Иисуса и Духа, найденные в Новом Завете, были объединены, чтобы сформировать концепцию Троицы — единое Божество, существующее в трех лицах и одной сущности . Концепция Троицы использовалась для противодействия альтернативным взглядам на то, как эти три связаны, и для защиты церкви от обвинений в поклонении двум или трем богам. [30]

Современная библейская наука в целом согласна с тем, что 1 Иоанна 5:7, встречающееся в латинских и греческих текстах после 4-го века и найденное в более поздних переводах, таких как перевод короля Якова, не может быть найдено в самых старых греческих и латинских текстах. Стих 7 известен как Иоаннова комма , которую большинство ученых считают более поздним добавлением более позднего переписчика или тем, что называется текстовой глоссой [31] , а не частью оригинального текста. [b] Этот стих гласит:

Ибо на Небесах три свидетельствуют: Отец, Слово и Святой Дух, и Сии три — едино.

Этот стих отсутствует в эфиопских, арамейских, сирийских, славянских, ранних армянских, грузинских и арабских переводах греческого Нового Завета. Он в основном встречается в латинских рукописях, хотя меньшинство греческих, славянских и поздних армянских рукописей содержат его. [32] [33] [34]

В посланиях Павла публичные, коллективные образцы религиозного поклонения Иисусу в раннем христианском сообществе отражают точку зрения Павла на божественный статус Иисуса в том, что ученые назвали «бинитарной» моделью или формой религиозной практики (поклонения) в Новом Завете, в которой «Бог» и Иисус тематизируются и призываются. [35] Иисус принимает молитву (1 Коринфянам 1:2; 2 Коринфянам 12:8–9), присутствие Иисуса исповедально призывают верующие (1 Коринфянам 16:22; Римлянам 10:9–13; Филиппийцам 2:10–11), люди крестятся во имя Иисуса (1 Коринфянам 6:11; Римлянам 6:3), Иисус является ссылкой в христианском общении на религиозную ритуальную трапезу ( Вечеря Господня ; 1 Коринфянам 11:17–34). [36] Иисус описывается как «существующий в самом образе Божием» (Филиппийцам 2:6) и имеющий «полноту Божества [живущую] в телесной форме» (Колоссянам 2:9). В некоторых стихах Иисус также напрямую назван Богом (Римлянам 9:5, [37] Титу 2:13, 2 Петра 1:1).

Евангелия изображают Иисуса как человека на протяжении большей части своего повествования, но «в конце концов человек обнаруживает, что он божественное существо, проявленное во плоти, и смысл текстов отчасти в том, чтобы сделать его высшую природу известной в своего рода интеллектуальном прозрении». [38] В Евангелиях Иисус описывается как прощающий грехи, что приводит некоторых теологов к мысли, что Иисус изображен как Бог. [39] Это происходит потому, что Иисус прощает грехи от имени других, люди обычно прощают только проступки против себя. Учителя закона рядом с Иисусом признают это и говорят:

«Почему этот человек так говорит? Он богохульствует! Кто может прощать грехи, кроме одного Бога?» Марка 2:7

Иисус также получает προσκύνησις ( proskynesis ) после воскресения, греческий термин, который либо выражает современный социальный жест поклонения вышестоящему, либо на коленях, либо в полном земном поклоне (в Матфея 18:26 раб совершает προσκύνησις своему господину, чтобы он не был продан после того, как не смог заплатить свои долги). Термин также может относиться к религиозному акту преданности божеству. Хотя Иисус получает προσκύνησις несколько раз в синоптических Евангелиях , можно сказать, что только несколько из них относятся к божественному поклонению. [40]

Это включает в себя Матфея 28:16–20, рассказ о том, как воскресший Иисус получает поклонение от своих учеников после провозглашения своей власти над космосом и своего постоянно продолжающегося присутствия с учениками (образуя включение с началом Евангелия, где Иисусу дано имя Эммануил, «Бог с нами», имя, которое намекает на постоянное присутствие Бога Израиля со своими последователями на протяжении всего Ветхого Завета (Бытие 28:15; Второзаконие 20:1). [41] [42] В то время как некоторые утверждали, что Матфея 28:19 было вставкой из-за его отсутствия в первых нескольких столетиях ранних христианских цитат, ученые в основном принимают отрывок как подлинный из-за его подтверждающих рукописных свидетельств и того, что он, по-видимому, либо цитируется в Дидахе (7:1–3) [43], либо, по крайней мере, отражен в Дидахе как часть общей традиции, из которой возникли и Матфей, и Дидахе. [44] Иисус получает божественное поклонение в Рассказы о событиях после воскресения далее отражены в Евангелии от Луки 24:52. [45] [46] [45]

В Деяниях описано раннее христианское движение как общественный культ, сосредоточенный вокруг Иисуса в нескольких отрывках. В Деяниях обычно отдельные христиане «призывают» имя Иисуса (9:14, 21; 22:16), идея, предшествующая ветхозаветным описаниям призывания имени ЯХВЕ как формы молитвы. История Стефана изображает Стефана, призывающего и взывающего к Иисусу в последние минуты своей жизни, чтобы получить его дух (7:59–60). Деяния далее описывают распространенную ритуальную практику введения новых членов в раннюю секту Иисуса путем крещения их во имя Иисуса (2:38; 8:16; 10:48; 19:5). [47] По словам Дейла Эллисона , в Деяниях явления Иисуса Павлу описываются как божественная теофания , стилизованная и отождествленная с Богом, ответственным за теофанию Иезекииля в Ветхом Завете. [48]

Евангелие от Иоанна рассматривается как направленное на то, чтобы подчеркнуть божественность Иисуса, представляя Иисуса как Логос , предсуществующий и божественный, с его первых слов: « В начале было Слово, и Слово было у Бога, и Слово было Бог » (Иоанна 1:1). [49] Евангелие от Иоанна заканчивается заявлением Фомы о том, что он верит, что Иисус был Богом: «Господь мой и Бог мой!» (Иоанна 20:28). [30] Современные ученые сходятся во мнении, что Иоанн 1:1 и Иоанн 20:28 отождествляют Иисуса с Богом. [50] Однако в статье в журнале Journal of Biblical Literature за 1973 год Филип Б. Харнер, почетный профессор религии в Гейдельбергском колледже , утверждал, что традиционный перевод Иоанна 1:1с («и Слово было Бог») неверен. Он поддерживает перевод Новой английской Библии Иоанна 1:1с: «и что было Бог, то было Слово». [51] Однако утверждение Харнера подверглось критике со стороны других ученых. [52] В той же статье Харнер также отметил, что: «Возможно, это предложение можно перевести как «Слово имело ту же природу, что и Бог». Это было бы одним из способов представления мысли Иоанна, которая, как я понимаю, заключается в том, что логос, не менее чем теос, имел природу теоса», что в его случае означает, что Слово является таким же полноправным Богом, как и личность, называемая «Богом». [53] [54] Иоанн также изображает Иисуса как агента творения вселенной. [55]

Некоторые предполагают, что Иоанн представляет иерархию [56] [57], когда цитирует Иисуса, говорящего: «Отец больше меня», — утверждение, к которому апеллировали нетринитаристские группы, такие как арианство . [58] Однако отцы Церкви, такие как Августин Блаженный и Фома Аквинский, утверждали, что это утверждение следует понимать как то, что Иисус говорит о своей человеческой природе. [59] [60]

Предшествующее израильское богословие считало, что Дух — это просто божественное присутствие самого Бога, [61] тогда как ортодоксальное христианское богословие считает, что Святой Дух — это отдельная личность самого Бога Отца. Это развитие начинается в начале Нового Завета, поскольку Дух Божий получает гораздо больше акцента и описания, чем в более ранних иудейских писаниях. В то время как в Ветхом Завете есть 75 ссылок на Духа и 35 — в небиблейских свитках Мертвого моря , Новый Завет, несмотря на свою значительно меньшую длину, упоминает Духа 275 раз. В дополнение к большему акценту и важности, придаваемым Духу в Новом Завете, Дух также описывается в гораздо более персонализированных и индивидуализированных терминах, чем раньше. [62] Ларри Уртадо пишет:

Более того, ссылки Нового Завета часто описывают действия, которые, кажется, придают Духу чрезвычайно личное качество, вероятно, даже больше, чем в Ветхом Завете или древних еврейских текстах. Так, например, Дух «вел» Иисуса в пустыню (Мк. 1:12; сравните «вел» в Мф. 4:1/Лк. 4:1), а Павел говорит о Духе, ходатайствующем за верующих (Рим. 8:26–27) и свидетельствующем верующим об их сыновнем статусе перед Богом (Рим. 8:14–16). Приведем другие примеры этого: в Деяниях Дух предупреждает Петра о прибытии посетителей от Корнилия (10:19), повелевает церкви в Антиохии послать Варнаву и Савла (13:2–4), направляет Иерусалимский собор к решению относительно обращенных язычников (15:28), в одном месте запрещает Павлу миссионерскую деятельность в Азии (16:6), а в другом месте предупреждает Павла (через пророческие пророчества) о предстоящих неприятностях в Иерусалиме (21:11). [62]

Святой Дух описывается как Бог в книге Деяний Апостолов.

Но Петр сказал: «Анания! для чего сатана вложил в твое сердце мысль солгать Духу Святому и утаить себе часть прибыли от земли? 4 Пока она оставалась непроданной, разве она не была твоей? И после продажи она не была в твоем распоряжении? Для чего ты замыслил это дело в сердце твоем? Ты солгал не человеку, а Богу». Деяния 5:3–4

Сначала Петр говорит, что Анания лжет Святому Духу, а затем говорит, что он лжет Богу.

В Новом Завете Дух не изображается как получатель культового поклонения, которое вместо этого обычно предлагается Богу Отцу и воскресшему/прославленному Иисусу. Хотя то, что впоследствии стало основным христианством, подтвердило уместность включения Духа в качестве получателя поклонения, что отражено в развитой форме Никейского Символа веры , возможно, наиболее близким к этому в Новом Завете является Матфея 28:19 и 2 Коринфянам 13:14, которые описывают Духа как предмет религиозного ритуала. [63]

По мере того, как арианские споры утихали, дебаты переместились с божественности Иисуса Христа на равенство Святого Духа Отцу и Сыну. С одной стороны, секта пневматомахов заявляла, что Святой Дух является личностью, низшей по сравнению с Отцом и Сыном. С другой стороны, каппадокийские отцы утверждали, что Святой Дух равен Отцу и Сыну по природе или сущности.

Хотя основным текстом, используемым в защиту божественности Святого Духа, был Матфей 28:19, каппадокийские отцы, такие как Василий Великий, приводили в качестве аргумента другие стихи, например: «Но Петр сказал: Анания! для чего ты допустил сатане вложить в сердце твое мысль солгать Духу Святому и утаить себе часть из доходов от земли? Пока она не была продана, разве она не была твоей? А после продажи не была ли она в твоем распоряжении? Для чего ты замыслил это дело в сердце твоем? Ты солгал не человекам, а Богу » (Деяния 5:3–4).

Другой отрывок, который цитировали Каппадокийские отцы, был: «Словом Господа сотворены небеса, и духом уст Его — все воинство их» (Псалом 33:6). Согласно их пониманию, поскольку «дыхание» и «дух» на иврите оба «רוּחַ» («ruach»), Псалом 33:6 раскрывает роли Сына и Святого Духа как сотворцов. И поскольку, по их мнению, [64] только святой Бог может создавать святые существа, такие как ангелы, Сын и Святой Дух должны быть Богом.

Еще один аргумент отцов-каппадокийцев, доказывающий, что Святой Дух имеет ту же природу, что и Отец и Сын, исходит из «Ибо кто знает, что в человеке, кроме духа, живущего в нем? Так и Божиих никто не постигает, кроме Духа Божия» (1 Коринфянам 2:11). Они рассуждали, что этот отрывок доказывает, что Святой Дух имеет такое же отношение к Богу, как и дух внутри нас к нам. [64]

Каппадокийские отцы также цитировали: «Разве не знаете, что вы храм Божий, и Дух Божий живет в вас?» (1 Коринфянам 3:16) и рассуждали, что было бы кощунством для низшего существа поселиться в храме Божьем, тем самым доказывая, что Святой Дух равен Отцу и Сыну. [65]

Они также объединили фразу «раб не знает, что делает господин его» (Иоанна 15:15) с 1 Коринфянам 2:11, пытаясь показать, что Святой Дух не является рабом Божьим, а потому равен Ему. [66]

Пневматомахи противоречили каппадокийским отцам, цитируя: «Не все ли они суть служебные духи, посылаемые на служение для тех, которые имеют наследовать спасение?» (Евреям 1:14), фактически утверждая, что Святой Дух ничем не отличается от других сотворенных ангельских духов. [67] Отцы Церкви не согласились, заявив, что Святой Дух больше ангелов, поскольку Святой Дух — это тот, кто дарует предвидение для пророчества (1 Коринфянам 12:8–10), чтобы ангелы могли возвещать грядущие события. [64]

Хотя разработанная доктрина Троицы не выражена явно в книгах, составляющих Новый Завет , она была впервые сформулирована, когда ранние христиане пытались понять отношения между Иисусом и Богом в своих библейских документах и предшествующих традициях. [14] По словам Маргарет Бейкер, тринитарное богословие имеет корни в дохристианских палестинских верованиях об ангелах. [69]

Раннее упоминание о трех «лицах» более поздних тринитарных доктрин появляется ближе к концу первого века, когда Климент Римский риторически спрашивает в своем послании о том, почему коррупция существует среди некоторых членов христианской общины: «Не один ли у нас Бог, и один Христос, и один благодатный Дух, излитый на нас, и одно призвание во Христе?» (1 Климент 46:6). [70] Похожий пример можно найти в Дидахе первого века , который предписывает христианам «крестить во имя Отца и Сына и Святого Духа». [71]

Игнатий Антиохийский также ссылается на все три лица около 110 г. н. э., призывая к послушанию «Христу, Отцу и Духу». [72] Хотя все эти ранние источники ссылаются на три лица Троицы, ни один из них не выражает полную божественность, равный статус или общее бытие, как это было разработано тринитариями в более поздние века. [ требуется ссылка ]

Псевдоним « Вознесение Исайи» , написанное где-то между концом первого и началом третьего века, содержит «прототринитарную» точку зрения, например, в своем повествовании о том, как обитатели шестого неба поют хвалу «первичному Отцу и его Возлюбленному Христу, и Святому Духу». [73]

Иустин Мученик (100 г. н. э. – ок. 165 г.) также пишет: «во имя Бога, Отца и Господа вселенной, и нашего Спасителя Иисуса Христа, и Святого Духа». [74] Иустин Мученик первым использовал большую часть терминологии, которая позже стала широко распространенной в кодифицированном тринитарном богословии. Например, он описывает, что Сын и Отец являются одним и тем же «существом» ( ousia ), но при этом являются различными лицами ( prosopa ), предвосхищая три лица ( hypostases ), которые появляются у Тертуллиана и более поздних авторов. Иустин описывает, как Иисус, Сын, отличается от Отца, но также происходит от Отца, используя аналогию с огнем (представляющим Сына), который зажигается от своего источника, факела (представляющего Отца). [75] В другом месте Иустин Мученик писал, что «мы поклоняемся ему [Иисусу Христу] с основанием, поскольку мы узнали, что он есть Сын самого Бога живого, и верим, что он на втором месте, а пророческий Дух на третьем» (1 Апология 13, ср. гл. 60). О христианском крещении он писал, что «во имя Бога, Отца и Господа вселенной, и нашего Спасителя Иисуса Христа, и Святого Духа, они затем принимают омовение водой», подчеркивая литургическое использование тринитарной формулы. [76]

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg/440px-Albrecht_Dürer_-_Adoration_of_the_Trinity_(Landauer_Altar)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Первым из ранних Отцов Церкви, который упоминал слово «Троица», был Феофил Антиохийский, писавший в конце II века. Он определяет Троицу как Бога, его Слово ( Логос ) и его Мудрость ( София ) [77] в контексте обсуждения первых трех дней творения, следуя ранней христианской практике определения Святого Духа как Мудрости Божией. [78]

Первая защита учения о Троице была сделана Тертуллианом , который родился около 150–160 гг. н. э., он явно «определил» Троицу как Отца, Сына и Святого Духа и защищал свое богословие от Праксея [79], хотя он отметил, что большинство верующих в его время не соглашались с его учением. [80]

Святые Иустин и Климент Александрийский упоминали все три лица Троицы в своих славословиях , а также святитель Василий в вечернем зажигании светильников. [81]

Оригена Александрийского (185 г. н. э. – ок. 253 г.) часто интерпретировали как субординациониста – верящего в общую божественность трех лиц, но не в их равенство. (Некоторые современные исследователи утверждают, что Ориген на самом деле мог быть антисубординационистом и что его собственное тринитарное богословие вдохновило тринитарное богословие более поздних каппадокийских отцов .) [82] [83]

Концепция Троицы может рассматриваться как значительно развивавшаяся в течение первых четырех столетий Отцами Церкви в ответ на теологические интерпретации, известные как адопционизм , савеллианство и арианство . Адопционизм был верой в то, что Иисус был обычным человеком, рожденным Иосифом и Марией, который стал Христом и Сыном Божьим при крещении. В 269 году Синоды Антиохии осудили Павла Самосатского за его адопционистское богословие, а также осудили термин homoousios ( ὁμοούσιος , «того же существа») в модалистском смысле, в котором он его использовал. [84]

Среди нетринитарных верований савеллианство учило, что Отец, Сын и Святой Дух по сути являются одним и тем же, разница лишь словесная, описывающая различные аспекты или роли одного существа. [85] За эту точку зрения Савеллий был отлучен от церкви за ересь в Риме около 220 г.

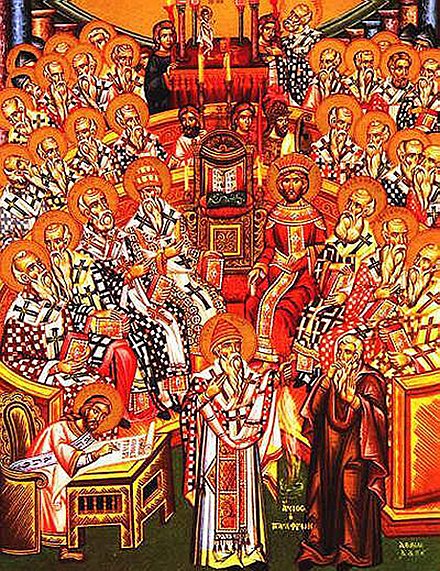

В четвертом веке арианство , как его традиционно понимают, [c] учило, что Отец существовал до Сына, который по природе не был Богом, а скорее изменчивым существом, которому было даровано достоинство стать «Сыном Божиим». [86] В 325 году Первый Никейский собор принял Никейский символ веры, который описывал Христа как «Бога от Бога, Света от Света, истинного Бога от истинного Бога, рожденного, несотворенного, единосущного Отцу», а «Святой Дух» — как тот, посредством которого « воплотился ... от Девы Марии ». [87] [88] (« Слово стало плотью и обитало с нами»). Относительно Отца и Сына символ веры использовал термин homoousios (единосущный), чтобы определить отношения между Отцом и Сыном. После более чем пятидесяти лет споров homoousios был признан отличительным признаком ортодоксии и был далее развит в формулу «три лица, одно существо».

В исповедании Первого Никейского собора, Никейском символе веры, мало говорится о Святом Духе. [89] На Первом Никейском соборе (325) все внимание было сосредоточено на отношениях между Отцом и Сыном, без каких-либо подобных заявлений о Святом Духе. В словах символа веры:

Веруем во единого Бога Отца Всемогущего, Творца всего видимого и невидимого. И во единого Господа Иисуса Христа, Сына Божия, рожденного от Отца [единородного; то есть из сущности Отца, Бога от Бога,] Света от Света, Бога истинного от Бога истинного, рожденного, несотворенного, единосущного Отцу; ... И [веруем] в Духа Святого. ...

Позднее, на Первом Константинопольском соборе (381 г.), Никейский символ веры был расширен и стал известен как Никео-Константинопольский символ веры, в котором говорилось, что Святой Дух почитается и прославляется вместе с Отцом и Сыном ( συμπροσκυνούμενον καὶ συνδοξαζόμενον ), что предполагает, что Он также был единосущным с ними:

Веруем во единого Бога Отца Всемогущего, Творца неба и земли, всего видимого и невидимого. И во единого Господа Иисуса Христа, Сына Божия единородного, рожденного от Отца прежде всех миров (эонов), Света от Света, Бога истинного от Бога истинного, рожденного, несотворенного, единосущного Отцу; ... И в Духа Святого, Господа и Подателя жизни, исходящего от Отца, с Отцом и Сыном спокланяемого и сславимого, говорившего через пророков ... [90]

Учение о божественности и личности Святого Духа было разработано Афанасием в последние десятилетия его жизни. [91] Он защищал и совершенствовал Никейскую формулу. [89] К концу IV века под руководством Василия Кесарийского , Григория Нисского и Григория Назианзина ( каппадокийских отцов ) учение в значительной степени достигло своей нынешней формы. [89]

Григорий Назианзин, Григорий Нисский и Василий Великий, описывая Троицу, видели, что различия между тремя божественными лицами заключаются исключительно в их внутренних божественных отношениях. Нет трех богов, Бог — одно божественное существо в трех лицах. [92] Там, где каппадокийские отцы использовали социальные аналогии для описания триединой природы Бога, Августин Гиппонский использовал психологическую аналогию. Он считал, что если человек создан по образу Бога, он создан по образу Троицы. Аналогия Августина для Троицы — это память, интеллект и воля в уме человека. Короче говоря, христианам не обязательно думать о трех лицах, когда они думают о Боге; они могут думать об одном лице. [93]

В конце VI века некоторые латиноязычные церкви добавили слова «и от Сына» ( Filioque ) к описанию исхождения Святого Духа, слова, которые не были включены в текст ни Никейским, ни Константинопольским соборами. [94] Это было включено в литургическую практику Рима в 1014 году . [95] Filioque в конечном итоге стало одной из главных причин раскола между Востоком и Западом в 1054 году и неудач неоднократных попыток объединения.

Григорий Назианзин говорил о Троице: «Как только я постигаю Единого, меня освещает великолепие Трех; как только я различаю Трех, меня снова переносит в Единое. Когда я думаю о любом из Трех, я думаю о Нем как о Целом, и мои глаза наполняются, и большая часть того, о чем я думаю, ускользает от меня. Я не могу постичь величие Единого, чтобы приписать большее величие остальному. Когда я созерцаю Троих вместе, я вижу только один факел и не могу разделить или измерить неделимый свет». [96]

Почитание Троицы сосредоточилось во французских монастырях в Туре и Аниане, где Бенедикт Анианский посвятил церковь аббатства Троице в 872 году. Праздничные дни не были установлены до 1091 года в Клюни и 1162 года в Кентербери, а папское сопротивление продолжалось до 1331 года. [81]

Baptism is generally conferred with the Trinitarian formula, "in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit".[97] Trinitarians identify this name with the Christian faith into which baptism is an initiation, as seen for example in the statement of Basil the Great (330–379): "We are bound to be baptized in the terms we have received, and to profess faith in the terms in which we have been baptized." The First Council of Constantinople (381) also says, "This is the Faith of our baptism that teaches us to believe in the Name of the Father, of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. According to this Faith there is one Godhead, Power, and Being of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit."[98] may be taken to indicate that baptism was associated with this formula from the earliest decades of the Church's existence. Other Trinitarian formulas found in the New Testament include in 2 Corinthians 13:14, 1 Corinthians 12:4–6, Ephesians 4:4–6, 1 Peter 1:2 and Revelation 1:4–5.[12][29]

Oneness Pentecostals demur from the Trinitarian view of baptism and emphasize baptism "in the name of Jesus Christ" only, what they hold to be the original apostolic formula.[99] For this reason, they often focus on the baptisms in Acts. Those who place great emphasis on the baptisms in Acts often likewise question the authenticity of Matthew 28:19 in its present form.[citation needed] Most scholars of New Testament textual criticism accept the authenticity of the passage, since there are no variant manuscripts regarding the formula,[43] and the extant form of the passage is attested in the Didache[100] and other patristic works of the 1st and 2nd centuries: Ignatius,[101] Tertullian,[102] Hippolytus,[103] Cyprian,[104] and Gregory Thaumaturgus.[105]

Commenting on Matthew 28:19, Gerhard Kittel states:

This threefold relation [of Father, Son and Spirit] soon found fixed expression in the triadic formulae in 2 Corinthians 13:14[106] and in 1 Corinthians 12:4–6.[107] The form is first found in the baptismal formula in Matthew 28:19 Did., 7. 1 and 3. ... [I]t is self-evident that Father, Son and Spirit are here linked in an indissoluble threefold relationship.[108]

In Trinitarian doctrine, God exists as three persons but is one being, having a single divine nature.[109] The members of the Trinity are co-equal and co-eternal, one in essence, nature, power, action, and will. As stated in the Athanasian Creed, the Father is uncreated, the Son is uncreated, and the Holy Spirit is uncreated, and all three are eternal without beginning.[110] "The Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit" are not names for different parts of God, but one name for God[111] because three persons exist in God as one entity.[112] They cannot be separate from one another. Each person is understood as having the identical essence or nature, not merely similar natures.[113]

According to the Eleventh Council of Toledo (675) "For, when we say: He who is the Father is not the Son, we refer to the distinction of persons; but when we say: the Father is that which the Son is, the Son that which the Father is, and the Holy Spirit that which the Father is and the Son is, this clearly refers to the nature or substance".[114]

The Fourth Lateran Council (1215) adds: "Therefore in God there is only a Trinity, not a quaternity, since each of the three persons is that reality – that is to say substance, essence or divine nature-which alone is the principle of all things, besides which no other principle can be found. This reality neither begets nor is begotten nor proceeds; the Father begets, the Son is begotten and the holy Spirit proceeds. Thus there is a distinction of persons but a unity of nature. Although therefore the Father is one person, the Son another person and the holy Spirit another person, they are not different realities, but rather that which is the Father is the Son and the holy Spirit, altogether the same; thus according to the orthodox and catholic faith they are believed to be consubstantial. "[115][116]

Clarification of the relationships among the three Trinitarian Persons (divine persons, different from the sense of a "human self") advanced in the Magisterial statement promulgated by the Council of Florence (1431–1449), though its formulation precedes the council: "These three persons are one God and not three gods, for the three are one substance, one essence, one nature, one Godhead, one infinity, one eternity, and everything (in them) is one where there is no opposition of relationship [relationis oppositio]".[d] Robert Magliola explains that most theologians have taken relationis oppositio in the "Thomist" sense, namely, the "opposition of relationship" [in English we would say "oppositional relationship"] is one of contrariety rather than contradiction. The only "functions" that are applied uniquely to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit respectively in Scripture are the following: "Paternity" to the Father, "Filiation" (Sonship) to the Son, and "Passive Spiration" or that which is "breathed out", to the Holy Spirit. Magliola goes on to explain:

Because such is the case (among other reasons), Karl Rahner rejects the "psychological" theories of Trinity which define the Father as Knower, for example, and the Son as the Known (i.e., Truth). Scripture in one place or another identifies Knowing with each of the three Persons all told. Which is to say, according to the relationis oppositio, Knowing (in our example) does not define the Persons [qua individual Persons] at all, but the Unity of God instead. (Scripture's attribution of Knowing to any one Person at any one time is said to be just "appropriated" to the Person: it does not really belong to that unique Person).[117]

Magliola, continuing the Rahnerian stance, goes on to explain that the Divine Persons necessarily relate to each other in terms of "pure negative reference", that is, the three "Is Not" relations represented in the Scutum Fidei diagram are in each case a pure or absolute "Is Not". This is the case because the relationis oppositio clause disallows the Persons to "share", qua Persons, the unique role that defines each of them. Lest he be misunderstood, Magliola, in a subsequent publication, makes sure to specify that each of the three Persons, while unique as a Person, is nonetheless—because of the Divine "consubstantiality" and "simplicity"—the one Reality that is God.[118]

There have been some different understandings of the Trinity among Christian theologians and denominations, including questions on issues such as: filioque, subordinationism, eternal generation of the Son and social trinitarianism.[citation needed]

Perichoresis (from Greek, "going around", "envelopment") is a term used by some scholars to describe the relationship among the members of the Trinity. The Latin equivalent for this term is circumincessio. This concept refers for its basis to John 10:38,14:11,14:20,[119] where Jesus is instructing the disciples concerning the meaning of his departure. His going to the Father, he says, is for their sake; so that he might come to them when the "other comforter" is given to them. Then, he says, his disciples will dwell in him, as he dwells in the Father, and the Father dwells in him, and the Father will dwell in them. This is so, according to the theory of perichoresis, because the persons of the Trinity "reciprocally contain one another, so that one permanently envelopes and is permanently enveloped by, the other whom he yet envelopes" (Hilary of Poitiers, Concerning the Trinity 3:1).[120] The most prominent exponent of perichoresis was John of Damascus (d. 749) who employed the concept as a technical term to describe both the interpenetration of the divine and human natures of Christ and the relationship between the hypostases of the Trinity.[121]

Perichoresis effectively excludes the idea that God has parts, but rather is a simple being. It also harmonizes well with the doctrine that the Christian's union with the Son in his humanity brings him into union with one who contains in himself, in Paul's words, "all the fullness of deity" and not a part.[e] Perichoresis provides an intuitive figure of what this might mean. The Son, the eternal Word, is from all eternity the dwelling place of God; he is the "Father's house", just as the Son dwells in the Father and the Spirit; so that, when the Spirit is "given", then it happens as Jesus said, "I will not leave you as orphans; for I will come to you."[122]

The term "immanent Trinity" focuses on who God is; the term "economic Trinity" focuses on what God does. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church,

The Fathers of the Church distinguish between theology (theologia) and economy (oikonomia). "Theology" refers to the mystery of God's inmost life within the Blessed Trinity and "economy" to all the works by which God reveals himself and communicates his life. Through the oikonomia the theologia is revealed to us; but conversely, the theologia illuminates the whole oikonomia. God's works reveal who he is in himself; the mystery of his inmost being enlightens our understanding of all his works. So it is, analogously, among human persons. A person discloses himself in his actions, and the better we know a person, the better we understand his actions.[123]

The whole divine economy is the common work of the three divine persons. For as the Trinity has only one and the same natures so too does it have only one and the same operation: "The Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit are not three principles of creation but one principle." However, each divine person performs the common work according to his unique personal property. Thus the Church confesses, following the New Testament, "one God and Father from whom all things are, and one Lord Jesus Christ, through whom all things are, and one Holy Spirit in whom all things are". It is above all the divine missions of the Son's Incarnation and the gift of the Holy Spirit that show forth the properties of the divine persons.[124]

The ancient Nicene theologians argued that everything the Trinity does is done by Father, Son, and Spirit working in unity with one will. The three persons of the Trinity always work inseparably, for their work is always the work of the one God. The Son's will cannot be different from the Father's because it is the Father's. They have but one will as they have but one being. Otherwise they would not be one God. On this point St. Basil said:

When then He says, "I have not spoken of myself", and again, "As the Father said unto me, so I speak", and "The word which ye hear is not mine, but [the Father's] which sent me", and in another place, "As the Father gave me commandment, even so I do", it is not because He lacks deliberate purpose or power of initiation, nor yet because He has to wait for the preconcerted key-note, that he employs language of this kind. His object is to make it plain that His own will is connected in indissoluble union with the Father. Do not then let us understand by what is called a "commandment" a peremptory mandate delivered by organs of speech, and giving orders to the Son, as to a subordinate, concerning what He ought to do. Let us rather, in a sense befitting the Godhead, perceive a transmission of will, like the reflexion of an object in a mirror, passing without note of time from Father to Son.[125]

According to Thomas Aquinas the Son prayed to the Father, became a minor to the angels, became incarnate, obeyed the Father as to his human nature; as to his divine nature the Son remained God: "Thus, then, the fact that the Father glorifies, raises up, and exalts the Son does not show that the Son is less than the Father, except in His human nature. For, in the divine nature by which He is equal to the Father, the power of the Father and the Son is the same and their operation is the same."[60] Aquinas stated that the mystery of the Son cannot be explicitly believed to be true without faith in the Trinity (ST IIa IIae, 2.7 resp. and 8 resp.).[126]

Athanasius of Alexandria explained that the Son is eternally one in being with the Father, temporally and voluntarily subordinate in his incarnate ministry.[127] Such human traits, he argued, were not to be read back into the eternal Trinity. Likewise, the Cappadocian Fathers also insisted there was no economic inequality present within the Trinity. As Basil wrote: "We perceive the operation of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to be one and the same, in no respect showing differences or variation; from this identity of operation we necessarily infer the unity of nature."[128]

The traditional theory of "appropriation" consists in attributing certain names, qualities, or operations to one of the Persons of the Trinity, not, however, to the exclusion of the others, but in preference to the others. This theory was established by the Latin Fathers of the fourth and fifth centuries, especially by Hilary of Poitiers, Augustine, and Leo the Great. In the Middle Ages, the theory was systematically taught by the Schoolmen such as Bonaventure.[129]

Augustine "coupled the doctrine of the Trinity with anthropology. Proceeding from the idea that humans are created by God according to the divine image, he attempted to explain the mystery of the Trinity by uncovering traces of the Trinity in the human personality".[130] The first key of his exegesis is an interpersonal analogy of mutual love. In De trinitate (399–419) he wrote,

We are now eager to see whether that most excellent love is proper to the Holy Spirit, and if it is not so, whether the Father, or the Son, or the Holy Trinity itself is love, since we cannot contradict the most certain faith and the most weighty authority of Scripture which says: "God is love".[f][131]

The Bible reveals it although only in the two neighboring verses 1 John 4:8.16, therefore one must ask if love itself is triune. Augustine found that it is, and consists of "three: the lover, the beloved, and the love."[g][132]

Reaffirming the theopaschite formula unus de trinitate passus est carne (meaning "One of the Trinity suffered in the flesh"),[133] Thomas Aquinas wrote that Jesus suffered and died as to his human nature, as to his divine nature he could not suffer or die. "But the commandment to suffer clearly pertains to the Son only in His human nature. ... And the way in which Christ was raised up is like the way He suffered and died, that is, in the flesh. For it says in 1 Peter (4:1): 'Christ having suffered in the flesh' ... then, the fact that the Father glorifies, raises up, and exalts the Son does not show that the Son is less than the Father, except in His human nature. For, in the divine nature by which He is equal to the Father."[134]

In the 1900s the recovery of a substantially different formula of theopaschism took place: at least unus de Trinitate passus est (meaning "not only in the flesh").[135] More specifically, World War II had an impact not only on the theodicy of Judaism with the Holocaust theology, but also on that of Christianity with a profound rethinking of its dogmatic theology. Deeply affected by the atomic bombs event,[136] as early as 1946 the Lutheran theologian Kazoh Kitamori published Theology of the Pain of God,[137] a theology of the Cross pushed up to the immanent Trinity. This concept was later taken by both Reformed and Catholic theology: in 1971 by Jürgen Moltmann's The Crucified God; in the 1972 "Preface to the Second Edition" of his 1969 German book Theologie der drei Tage (English translation: The Mystery of Easter) by Hans Urs von Balthasar, who took a cue from Revelation 13:8 (Vulgate: agni qui occisus est ab origine mundi, NIV: "the Lamb who was slain from the creation of the world") to explore the "God is love" idea as an "eternal super-kenosis".[138] In the words of von Balthasar: "At this point, where the subject undergoing the 'hour' is the Son speaking with the Father, the controversial 'Theopaschist formula' has its proper place: 'One of the Trinity has suffered.' The formula can already be found in Gregory Nazianzen: 'We needed a ... crucified God'."[139]

But if theopaschism indicates only a Christological kenosis (or kenotic Christology), instead von Balthasar supports a Trinitarian kenosis:[140] "The persons of the Trinity constitute themselves as who they are through the very act of pouring themselves out for each other".[141] The underlying question is if the three Persons of the Trinity can live a self-love (amor sui), as well as if for them, with the conciliar dogmatic formulation in terms that today we would call ontotheological, it is possible that the aseity (causa sui) is valid. If the Father is not the Son or the Spirit since the generator/begetter is not the generated/begotten nor the generation/generative process and vice versa, and since the lover is neither the beloved nor the love dynamic between them and vice versa, Christianity has provided as a response a concept of divine ontology and love different from common sense (omniscience, omnipotence, omnibenevolence, impassibility, etc.):[142][143] an oblative, sacrificial, martyrizing, crucifying, precisely kenotic concept.

Benjamin B. Warfield saw a principle of subordination in the "modes of operation" of the Trinity, but was also hesitant to ascribe the same to the "modes of subsistence" in relation of one to another. While noting that it is natural to see a subordination in function as reflecting a similar subordination in substance, he suggests that this might be the result of "an agreement by Persons of the Trinity – a 'Covenant' as it is technically called – by virtue of which a distinct function in the work of redemption is assumed by each."[144]

Today, several analogies for the Trinity abound. The comparison is sometimes made between the triune God and H2O.[145][146] Just as H2O can come in three distinct forms (liquid, solid, gas), so God appears as Father, Son, Spirit.[145][146] The mathematical analogy, "1+1+1=3, but 1x1x1=1" is also used to explain the Trinity.[145]

According to Eusebius, Constantine suggested the term homoousios at the Council of Nicaea, though most scholars have doubted that Constantine had such knowledge and have thought that most likely Hosius had suggested the term to him.[147] Constantine later changed his view about the Arians, who opposed the Nicene formula, and supported the bishops who rejected the formula,[148] as did several of his successors, the first emperor to be baptized in the Nicene faith being Theodosius the Great, emperor from 379 to 395.[149]

Christians confess that the Trinity is fundamentally incomprehensible, and thus Christian confessions tend to maintain the doctrine as it is revealed in Scripture, but do not attempt to exhaustively analyse it or set forth its essence comprehensively, as Louis Berkhof describes in his Systematic Theology.

The Trinity is a mystery, not merely in the Biblical sense that it is a truth, which is formerly hidden, but is now revealed; but in the sense that man cannot comprehend it and make it intelligible. It is intelligible in some of its relations and modes of manifestation, but unintelligible in its essential nature. [... The Church] has never tried to explain the mystery of the Trinity, but only sought to formulate the doctrine of the Trinity in such a manner that the errors which endangered it were warded off.[150]

Nontrinitarianism (or antitrinitarianism) refers to Christian belief systems that reject the doctrine of the Trinity as found in the Nicene Creed as not having a scriptural origin. Nontrinitarian views differ widely on the nature of God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit. Various nontrinitarian views, such as Adoptionism, Monarchianism, and Arianism existed prior to the formal definition of the Trinity doctrine in AD 325, 360, and 431, at the Councils of Nicaea, Constantinople, and Ephesus, respectively.[151] Following the adoption of trinitarianism at Constantinople in 381, Arianism was driven from the Empire, retaining a foothold amongst the Germanic tribes. When the Franks converted to Catholicism in 496, however, it gradually faded out.[86] Nontrinitarianism was later renewed in the Gnosticism of the Cathars in the 11th through 13th centuries, in the Age of Enlightenment of the 18th century, and in some groups arising during the Second Great Awakening of the 19th century.[h]

Arianism was condemned as heretical by the First Council of Nicaea and, lastly, with Sabellianism by the Second Ecumenical Council (Constantinople, 381 CE).[152] Adoptionism was declared as heretical by the Ecumenical Council of Frankfurt, convened by the Emperor Charlemagne in 794 for the Latin West Church.[153]

Modern nontrinitarian groups or denominations include Christadelphians, Christian Science, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Dawn Bible Students, Iglesia ni Cristo, Jehovah's Witnesses, Living Church of God, Members Church of God International, Oneness Pentecostals, La Luz del Mundo, the Seventh Day Church of God, Unitarian Christians, United Church of God, and The Shepherd's Chapel.

As pointed out by Jonathan Israel,[154] the 17th Century Dutch Republic was more religiously tolerant than other European countries of the time, but its dominant Calvinist Church drew the line at groups who denied the Trinity; this was considered an intolerable aberration, and such groups were subject to various forms of persecution in the Netherlands.

John William Colenso argued that the Book of Enoch implies a Trinitarian-esque view of God, seeing the "Lord of the spirits", the "Elected one" and the "Divine power" each partaking of the name of God.[155]

Judaism maintains a tradition of monotheism that excludes the possibility of a Trinity.[156] In Judaism, God is understood to be the absolute one, indivisible, and incomparable being which is the ultimate cause of all existence.

Some Kabbalist writings have a Trinitarian-esque view of God, speaking of "stages of God's being, aspects of the divine personality", with God being "three hidden lights, which constitute one essence and one root". Some Jewish philosophers additionally saw God as a "thinker, thinking and thought", taking from Augustinian analogies.[157] The Zohar additionally says that "God is they, and they are it".

Philo of Alexandria recognized a threefold character of God, but had many differences from the Christian view of the Trinity.[158]

Islam considers Jesus to be a prophet, but not divine,[156] and God to be absolutely indivisible (a concept known as tawhid).[159] Several verses of the Quran state that the doctrine of the Trinity is blasphemous.

Indeed, disbelievers have said, "Truly, Allah is Messiah, son of Mary." But Messiah said, "Children of Israel! Worship Allah, my lord and your lord." Indeed, whoever associates partners with Allah, surely Allah has forbidden them from Heaven, and fire is their resort. And there are no helpers for the wrongdoers. Indeed, disbelievers have said, "Truly, Allah is a third of three." Yet, there is no god except One God, and if they do not desist from what they say, a grievous punishment befalls the disbelievers. Will they not turn to Allah and ask His forgiveness? For Allah is most forgiving and merciful. Is not Messiah, son of Mary, only a messenger? Indeed, messengers had passed away prior to him. And his mother was an upright woman. They both ate food. Observe how we explain the signs for them, then observe how they turn away (from truth)!

— Quran 5:72–75[160]

Interpretation of these verses by modern scholars has been varied. Verse 5:73 has been interpreted as a potential criticism of Syriac literature that references Jesus as "the third of three" and thus an attack on the view that Christ was divine.[161] Another interpretation is that this passage should be studied from a rhetorical perspective; so as not to be an error, but an intentional misrepresentation of the doctrine of the Trinity in order to demonstrate its absurdity from an Islamic perspective.[162] David Thomas states that verse 5:116 need not be seen as describing actually professed beliefs, but rather, giving examples of shirk (claiming divinity for beings other than God) and a "warning against excessive devotion to Jesus and extravagant veneration of Mary, a reminder linked to the central theme of the Qur'an that there is only one God and He alone is to be worshipped."[159] When read in this light, it can be understood as an admonition, "Against the divinization of Jesus that is given elsewhere in the Qur'an and a warning against the virtual divinization of Mary in the declaration of the fifth-century church councils that she is 'God-bearer'." Similarly, Gabriel Reynolds, Sidney Griffith and Mun'im Sirry argue that this quranic verse is to be understood as an intentional caricature and rhetorical statement to warn from the dangers of deifiying Jesus or Mary.[163][164] It has been suggested that the Islamic representation of the doctrine of the Trinity may derive from its description in some texts of Manichaeism "where we encounter a trinity, consisting of a Father, a Mother of Life / the Living Spirit and the Original Man".[165]

The Trinity is most commonly seen in Christian art with the Spirit represented by a dove, as specified in the Gospel accounts of the Baptism of Christ; he is nearly always shown with wings outspread. However depictions using three human figures appear occasionally in most periods of art.[166]

The Father and the Son are usually differentiated by age, and later by dress, but this too is not always the case. The usual depiction of the Father as an older man with a white beard may derive from the biblical Ancient of Days, which is often cited in defense of this sometimes controversial representation. However, in Eastern Orthodoxy the Ancient of Days is usually understood to be God the Son, not God the Father (see below)—early Byzantine images show Christ as the Ancient of Days,[167] but this iconography became rare. When the Father is depicted in art, he is sometimes shown with a halo shaped like an equilateral triangle, instead of a circle. The Son is often shown at the Father's right hand (Acts 7:56). He may be represented by a symbol—typically the Lamb (agnus dei) or a cross—or on a crucifix, so that the Father is the only human figure shown at full size. In early medieval art, the Father may be represented by a hand appearing from a cloud in a blessing gesture, for example in scenes of the Baptism of Christ. Later, in the West, the Throne of Mercy (or "Throne of Grace") became a common depiction. In this style, the Father (sometimes seated on a throne) is shown supporting either a crucifix[168] or, later, a slumped crucified Son, similar to the Pietà (this type is distinguished in German as the Not Gottes),[169] in his outstretched arms, while the Dove hovers above or in between them. This subject continued to be popular until the 18th century at least.

By the end of the 15th century, larger representations, other than the Throne of Mercy, became effectively standardised, showing an older figure in plain robes for the Father, Christ with his torso partly bare to display the wounds of his Passion, and the dove above or around them. In earlier representations both Father, especially, and Son often wear elaborate robes and crowns. Sometimes the Father alone wears a crown, or even a papal tiara.

In the later part of the Christian Era, in Renaissance European iconography, the Eye of Providence began to be used as an explicit image of the Christian Trinity and associated with the concept of Divine Providence. Seventeenth-century depictions of the Eye of Providence sometimes show it surrounded by clouds or sunbursts.[170]

The concept of the Trinity was made visible in the Heiligen-Geist-Kapelle in Bruck an der Mur, Austria, with a ground plan of an equilateral triangle with beveled corners.[171]

The Trinity has traditionally been a subject matter of strictly theological works focused on proving the doctrine of the Trinity and defending it against its critics. In recent years, however, the Trinity has made an entrance into the world of (Christian) literature through books such as The Shack, published in 2007 and The Trinity Story, published in 2021.

Nature answers the question what we are; person answers the question who we are. [...] Nature is the source of our operations, person does them.

Trinitarian formulas are found in New Testament books such as 1 Peter 1:2; and 2 Cor 13:13. But the formula used by John the mystery-seer is unique. Perhaps it shows John's original adaptation of Paul's dual formula.

The Armenian manuscripts, which favour the reading of the Vulgate, are admitted to represent a Latin influence which dates from the twelfth century

Popular analogies for the Trinity abound. The comparison is sometimes made between the triune God and H2O. Just as H2O can come in three distinct forms (liquid, solid, gas), so God appears as Father, Son, Spirit. Or just as the sun cannot be separated from its rays of light and its felt heat, so the Son is the ray of the Father and the spirit is the heat of God. Or, to use a mathematical analogy: 1+1+1=3, but 1x1x1=1.

Christians have always used various analogies to help make sense of the Trinity. Water, for example, can exist in three different states, as liquid, steam or ice. It is once substance (H2O) yet appears in three distinct forms.

[In the 2nd century,] Jesus was either regarded as the man whom God hath chosen, in whom the Deity or the Spirit of God dwelt, and who, after being tested, was adopted by God and invested with dominion, (Adoptionist Christology); or Jesus was regarded as a heavenly spiritual being (the highest after God) who took flesh, and again returned to heaven after the completion of his work on earth (pneumatic Christology)

sabellian heresy council constantinople.