Коммунизм (от лат. communis , «общий, всеобщий») [1] [2] — социально-политическая , философская и экономическая идеология в социалистическом движении , [1] целью которой является создание коммунистического общества , социально-экономического порядка, основанного на общей собственности на средства производства , распределения и обмена, который распределяет продукты среди всех членов общества на основе потребностей. [3] [4] [5] Коммунистическое общество подразумевает отсутствие частной собственности и социальных классов , [1] и, в конечном итоге, денег [6] и государства (или национального государства ). [7] [8] [9]

Коммунисты часто стремятся к добровольному государству самоуправления, но не согласны со средствами достижения этой цели. Это отражает различие между более либертарианским социалистическим подходом к коммунизации , революционной спонтанности и рабочему самоуправлению и более авторитарным авангардистским или коммунистическим партийно -ориентированным подходом через развитие социалистического государства , за которым следует отмирание государства . [10] Как одна из основных идеологий в политическом спектре , коммунистические партии и движения были описаны как радикально-левые или крайне левые. [11] [12] [примечание 1]

На протяжении всей истории развивались различные варианты коммунизма , включая анархический коммунизм , марксистские школы мысли и религиозный коммунизм , среди прочих. Коммунизм охватывает множество школ мысли, которые в целом включают марксизм , ленинизм и либертарианский коммунизм, а также политические идеологии, сгруппированные вокруг них. Все эти различные идеологии в целом разделяют анализ того, что нынешний порядок общества проистекает из капитализма , его экономической системы и способа производства , что в этой системе есть два основных социальных класса, что отношения между этими двумя классами являются эксплуататорскими и что эта ситуация может быть в конечном итоге разрешена только посредством социальной революции . [20] [примечание 2] Эти два класса — пролетариат , который составляет большинство населения в обществе и должен продавать свою рабочую силу , чтобы выжить, и буржуазия , небольшое меньшинство, которое извлекает прибыль из использования рабочего класса посредством частной собственности на средства производства. [22] Согласно этому анализу, коммунистическая революция приведет к власти рабочий класс, [23] и, в свою очередь, установит общее владение имуществом, основной элемент в преобразовании общества в сторону коммунистического способа производства . [24] [25] [26]

Коммунизм в его современной форме вырос из социалистического движения во Франции XVIII века , после Французской революции . Критика идеи частной собственности в эпоху Просвещения XVIII века через таких мыслителей, как Габриэль Бонно де Мабли , Жан Мелье , Этьен-Габриэль Морелли , Анри де Сен-Симон и Жан-Жак Руссо во Франции. [27] Во время потрясений Французской революции коммунизм возник как политическая доктрина под эгидой Франсуа-Ноэля Бабефа , Николя Рестифа де ла Бретонна и Сильвена Марешаля , всех из которых можно считать прародителями современного коммунизма, по словам Джеймса Х. Биллингтона . [28] [1] В 20 веке к власти пришли несколько якобы коммунистических правительств, исповедовавших марксизм-ленинизм и его варианты, [29] [примечание 3] сначала в Советском Союзе после русской революции 1917 года, а затем в некоторых частях Восточной Европы, Азии и нескольких других регионах после Второй мировой войны . [35] Как один из многих типов социализма , коммунизм стал доминирующей политической тенденцией, наряду с социал-демократией , в международном социалистическом движении к началу 1920-х годов. [36]

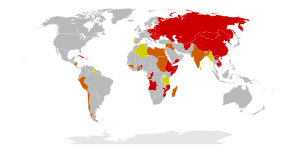

В течение большей части 20-го века около трети населения мира жило при коммунистических правительствах. Эти правительства характеризовались однопартийным правлением коммунистической партии, отказом от частной собственности и капитализма, государственным контролем экономической деятельности и средств массовой информации , ограничениями свободы вероисповедания и подавлением оппозиции и инакомыслия. С распадом Советского Союза в 1991 году несколько ранее коммунистических правительств полностью отказались от коммунистического правления или отменили его. [1] [37] [38] После этого осталось лишь небольшое количество номинально коммунистических правительств, таких как Китай , [39] Куба , Лаос , Северная Корея , [примечание 4] и Вьетнам . [46] За исключением Северной Кореи, все эти государства начали допускать большую экономическую конкуренцию, сохраняя при этом однопартийное правление. [1] Упадок коммунизма в конце 20-го века был приписан изначальной неэффективности коммунистической экономики и общей тенденции коммунистических правительств к авторитаризму и бюрократии . [1] [46] [47]

В то время как возникновение Советского Союза как первого в мире номинально коммунистического государства привело к широко распространенной ассоциации коммунизма с советской экономической моделью , некоторые ученые утверждают, что на практике эта модель функционировала как форма государственного капитализма . [48] [49] Общественная память о коммунистических государствах 20-го века описывалась как поле битвы между анти-антикоммунизмом и антикоммунизмом . [50] Многие авторы писали о массовых убийствах при коммунистических режимах и уровнях смертности , [примечание 5], таких как избыточная смертность в Советском Союзе при Иосифе Сталине , [примечание 6] , которые остаются спорными, поляризованными и обсуждаемыми темами в академических кругах, историографии и политике при обсуждении коммунизма и наследия коммунистических государств. [68] [69]

Коммунизм происходит от французского слова communisme , сочетания латинского корня communis (что буквально означает общий ) и суффикса isme ( действие, практика или процесс выполнения чего-либо ) . [70] [71] Семантически communis можно перевести как «сообщества или для сообщества», в то время как isme — это суффикс, который указывает на абстракцию в состояние, условие, действие или доктрину . Коммунизм можно интерпретировать как «состояние бытия сообщества или для сообщества»; эта семантическая конституция привела к многочисленным использованиям слова в его эволюции. До того, как стать связанным с его более современной концепцией экономической и политической организации, оно изначально использовалось для обозначения различных социальных ситуаций. После 1848 года коммунизм стал в первую очередь ассоциироваться с марксизмом , наиболее конкретно воплощенным в «Манифесте Коммунистической партии» , который предложил определенный тип коммунизма. [1] [72]

Одно из первых употреблений слова в его современном смысле содержится в письме, отправленном Виктором д'Юпеем Николя Рестифу де ла Бретонну около 1785 года, в котором д'Юпей описывает себя как auteur Communiste («коммунистический автор»). [73] В 1793 году Рестиф впервые использовал communisme для описания общественного порядка, основанного на эгалитаризме и общем владении имуществом. [74] Рестиф продолжал часто использовать этот термин в своих работах и был первым, кто описал коммунизм как форму правления . [75] Джону Гудвину Бармби приписывают первое использование слова communisme на английском языке, около 1840 года. [70]

С 1840-х годов термин коммунизм обычно отличался от социализма . Современное определение и использование термина социализм установилось к 1860-м годам, став преобладающим над альтернативными терминами, такими как ассоцианизм ( фурьеризм ), мутуализм или кооператив , которые ранее использовались как синонимы. Между тем, термин коммунизм в этот период вышел из употребления. [76]

Раннее различие между коммунизмом и социализмом заключалось в том, что последний был нацелен только на социализацию производства , тогда как первый был нацелен на социализацию как производства, так и потребления (в форме общего доступа к конечным благам ). [5] Это различие можно наблюдать в коммунизме Маркса, где распределение продуктов основано на принципе « каждому по его потребностям », в отличие от социалистического принципа « каждому по его вкладу ». [25] Социализм был описан как философия, стремящаяся к распределительной справедливости, а коммунизм как подмножество социализма, которое предпочитает экономическое равенство как форму распределительной справедливости. [77]

В Европе XIX века использование терминов коммунизм и социализм в конечном итоге соответствовало культурному отношению приверженцев и противников к религии . В европейском христианском мире коммунизм считался атеистическим образом жизни. В протестантской Англии коммунизм был слишком фонетически похож на обряд причастия в Римско-католической церкви , поэтому английские атеисты называли себя социалистами. [78] Фридрих Энгельс утверждал, что в 1848 году, во время первой публикации «Манифеста коммунистической партии» , [79] социализм был респектабельным на континенте, в то время как коммунизм — нет; оуэниты в Англии и фурьеристы во Франции считались респектабельными социалистами, в то время как движения рабочего класса, которые «провозгласили необходимость тотальных социальных изменений», называли себя коммунистами . Эта последняя ветвь социализма породила коммунистические работы Этьена Кабе во Франции и Вильгельма Вейтлинга в Германии. [80] В то время как либеральные демократы смотрели на Революцию 1848 года как на демократическую революцию , которая в конечном итоге обеспечила свободу, равенство и братство , марксисты осудили 1848 год как предательство идеалов рабочего класса буржуазией, безразличной к законным требованиям пролетариата . [ 81]

К 1888 году марксисты стали использовать термин социализм вместо коммунизма , который стал считаться старомодным синонимом первого. Только в 1917 году, с Октябрьской революцией , социализм стал использоваться для обозначения отдельной стадии между капитализмом и коммунизмом. Эта промежуточная стадия была концепцией, введенной Владимиром Лениным в качестве средства защиты большевистского захвата власти от традиционной марксистской критики, что производительные силы России были недостаточно развиты для социалистической революции . [24] Различие между коммунистическим и социалистическим как описаниями политических идеологий возникло в 1918 году после того, как Российская социал-демократическая рабочая партия переименовала себя в Коммунистическую партию Советского Союза , в результате чего прилагательное коммунистический стало использоваться для обозначения социалистов, которые поддерживали политику и теории большевизма, ленинизма , а позднее, в 1920-х годах, и марксизма -ленинизма . [82] Несмотря на это общепринятое употребление, коммунистические партии также продолжали называть себя социалистами, преданными социализму. [76]

Согласно Оксфордскому справочнику Карла Маркса , «Маркс использовал много терминов для обозначения посткапиталистического общества – позитивный гуманизм, социализм, коммунизм, царство свободной индивидуальности, свободная ассоциация производителей и т. д. Он использовал эти термины как полностью взаимозаменяемые. Представление о том, что «социализм» и «коммунизм» являются различными историческими этапами, чуждо его работам и вошло в лексикон марксизма только после его смерти». [83] Согласно Британской энциклопедии , «То, чем именно коммунизм отличается от социализма, долгое время было предметом споров, но это различие во многом основывается на приверженности коммунистов революционному социализму Карла Маркса». [1]

В Соединенных Штатах коммунизм широко используется как уничижительный термин как часть Красной угрозы , во многом как социализм , и в основном по отношению к авторитарному социализму и коммунистическим государствам . Возникновение Советского Союза как первого в мире номинально коммунистического государства привело к широкой ассоциации термина с марксизмом-ленинизмом и моделью экономического планирования советского типа . [1] [84] [85] В своем эссе «Осуждение нацизма и коммунизма» [86] Мартин Малия определяет категорию «общий коммунизм» как любое коммунистическое политическое партийное движение, возглавляемое интеллектуалами ; этот обобщающий термин позволяет объединить такие разные режимы , как радикальный советский индустриализм и антиурбанизм Красных кхмеров . [87] По словам Александра Даллина , идея объединить разные страны, такие как Афганистан и Венгрия , не имеет адекватного объяснения. [88]

В то время как термин «коммунистическое государство» используется западными историками, политологами и средствами массовой информации для обозначения стран, управляемых коммунистическими партиями, сами эти социалистические государства не называли себя коммунистическими и не заявляли, что достигли коммунизма; они называли себя социалистическим государством, которое находится в процессе построения коммунизма. [89] Термины, используемые коммунистическими государствами, включают национально-демократические , народно-демократические , социалистически ориентированные и рабочие и крестьянские государства. [90]

По словам Ричарда Пайпса , [91] идея бесклассового , эгалитарного общества впервые возникла в Древней Греции . С 20-го века в этом контексте рассматривался Древний Рим , а также такие мыслители, как Аристотель , Цицерон , Демосфен , Платон и Тацит . Платон, в частности, рассматривался как возможный коммунистический или социалистический теоретик, [92] или как первый автор, серьезно рассмотревший коммунизм. [93] Движение Маздака V века в Персии (современный Иран) было описано как коммунистическое за то, что оно бросило вызов огромным привилегиям знатных классов и духовенства , критиковало институт частной собственности и стремилось создать эгалитарное общество. [94] [95] В то или иное время существовали различные небольшие коммунистические общины, как правило, вдохновленные религиозными текстами . [53]

В средневековой христианской церкви некоторые монашеские общины и религиозные ордена делили свою землю и другую собственность. Секты, считавшиеся еретическими, такие как вальденсы, проповедовали раннюю форму христианского коммунизма . [96] [97] Как резюмируют историки Янзен Род и Макс Стэнтон, гуттериты верили в строгое соблюдение библейских принципов, церковную дисциплину и практиковали форму коммунизма. По их словам, гуттериты «установили в своих общинах строгую систему Ordnungen, которые представляли собой своды правил и положений, регулирующих все аспекты жизни и обеспечивающих единую перспективу. Как экономическая система, коммунизм был привлекателен для многих крестьян, которые поддерживали социальную революцию в Центральной Европе шестнадцатого века». [98] Эта связь была подчеркнута в одном из ранних произведений Карла Маркса ; Маркс утверждал, что «[как] Христос является посредником, которому человек передает всю свою божественность, все свои религиозные узы, так и государство является посредником, которому он передает все свое безбожие, всю свою человеческую свободу». [99] Томас Мюнцер возглавлял крупное анабаптистское коммунистическое движение во время Немецкой крестьянской войны , которую Фридрих Энгельс проанализировал в своей работе 1850 года «Крестьянская война в Германии» . Марксистский коммунистический этос, направленный на единство, отражает христианское универсалистское учение о том, что человечество едино и что есть только один бог, который не делает различий между людьми. [100]

Коммунистическая мысль также была прослежена до работ английского писателя XVI века Томаса Мора . [101] В своем трактате 1516 года под названием «Утопия» Мор изобразил общество, основанное на общем владении собственностью, правители которого управляли ею посредством применения разума и добродетели . [102] Марксистский коммунистический теоретик Карл Каутский , который популяризировал марксистский коммунизм в Западной Европе больше, чем любой другой мыслитель, за исключением Энгельса, опубликовал «Томас Мор и его утопия» , работу о Море, чьи идеи можно было бы считать «проблеском современного социализма», по словам Каутского. Во время Октябрьской революции в России Владимир Ленин предложил посвятить памятник Мору, наряду с другими важными западными мыслителями. [103]

В XVII веке коммунистическая мысль снова появилась в Англии, где религиозная группа пуритан, известная как диггеры, выступала за отмену частной собственности на землю. В своей работе 1895 года «Кромвель и коммунизм» [ 104] Эдуард Бернштейн утверждал, что несколько групп во время Гражданской войны в Англии (особенно диггеры) поддерживали четкие коммунистические, аграрно-религиозные идеалы и что отношение Оливера Кромвеля к этим группам было в лучшем случае неоднозначным и часто враждебным. [105] [106] Критика идеи частной собственности продолжалась и в эпоху Просвещения XVIII века такими мыслителями, как Габриэль Бонно де Мабли , Жан Мелье , Этьен-Габриэль Морелли и Жан-Жак Руссо во Франции. [107] Во время потрясений Французской революции коммунизм возник как политическая доктрина под эгидой Франсуа-Ноэля Бабефа , Николя Рестифа де ла Бретонна и Сильвена Марешаля , каждого из которых можно считать прародителями современного коммунизма, по словам Джеймса Х. Биллингтона . [28]

В начале 19 века различные социальные реформаторы основали общины, основанные на общей собственности. В отличие от многих предыдущих коммунистических общин, они заменили религиозный акцент на рациональную и филантропическую основу. [108] Среди них выделялись Роберт Оуэн , основавший Нью-Хармони, штат Индиана , в 1825 году, и Шарль Фурье , последователи которого организовали другие поселения в Соединенных Штатах, такие как Брук-Фарм в 1841 году . [1] В своей современной форме коммунизм вырос из социалистического движения в Европе 19 века. По мере развития промышленной революции критики-социалисты обвиняли капитализм в нищете пролетариата — нового класса городских фабричных рабочих, которые трудились в часто опасных условиях. Главными среди этих критиков были Маркс и его соратник Энгельс. В 1848 году Маркс и Энгельс предложили новое определение коммунизма и популяризировали этот термин в своей знаменитой брошюре « Манифест коммунистической партии» . [1]

В 1917 году Октябрьская революция в России создала условия для прихода к государственной власти большевиков Владимира Ленина , что стало первым случаем, когда открыто коммунистическая партия достигла такого положения. Революция передала власть Всероссийскому съезду Советов , на котором большевики имели большинство. [109] [110] [111] Это событие вызвало множество практических и теоретических дебатов в марксистском движении, поскольку Маркс утверждал, что социализм и коммунизм будут построены на фундаменте, заложенном самым передовым капиталистическим развитием; однако Российская империя была одной из беднейших стран в Европе с огромным, в основном неграмотным крестьянством и меньшинством промышленных рабочих. Маркс предостерегал от попыток «превратить мой исторический очерк генезиса капитализма в Западной Европе в историко-философскую теорию arche générale , навязанного судьбой каждому народу, каковы бы ни были исторические обстоятельства, в которых он находится», [112] и заявлял, что Россия могла бы перескочить через стадию буржуазного правления с помощью Общины . [113] [примечание 7] Умеренные меньшевики (меньшинство) выступали против плана Ленина большевиков (большинство) социалистической революции до того, как капиталистический способ производства был более полно развит. Успешное восхождение большевиков к власти было основано на таких лозунгах, как «Мир, хлеб и земля», которые использовали массовое общественное желание положить конец участию России в Первой мировой войне , требование крестьян провести земельную реформу и народную поддержку Советов . [117] 50 000 рабочих приняли резолюцию в пользу большевистского требования о передаче власти Советам [ 118] [119] Правительство Ленина также ввело ряд прогрессивных мер, таких как всеобщее образование , здравоохранение и равные права для женщин . [120] [121] [122] Начальный этап Октябрьской революции, который включал штурм Петрограда, прошел в основном без человеческих жертв . [123] [124] [125] [ нужна страница ]

К ноябрю 1917 года Временное правительство России было широко дискредитировано своей неспособностью выйти из Первой мировой войны, провести земельную реформу или созвать Учредительное собрание России для разработки конституции, оставив советы фактически контролировать страну. Большевики перешли к передаче власти Второму Всероссийскому съезду Советов рабочих и солдатских депутатов в Октябрьской революции; после нескольких недель обсуждений левые эсеры сформировали коалиционное правительство с большевиками с ноября 1917 года по июль 1918 года, в то время как правая фракция партии социалистов-революционеров бойкотировала советы и осудила Октябрьскую революцию как незаконный переворот . На выборах в Учредительное собрание России 1917 года социалистические партии набрали более 70% голосов. Большевики одержали явную победу в городских центрах и получили около двух третей голосов солдат на Западном фронте, получив 23,3% голосов; эсеры заняли первое место благодаря поддержке сельского крестьянства страны, которое в основном голосовало за один вопрос , а именно за земельную реформу, получив 37,6%, в то время как Украинский социалистический блок занял третье место с отставанием в 12,7%, а меньшевики заняли разочаровывающее четвертое место с 3,0%. [126]

Большинство мест в партии социалистов-революционеров досталось правой фракции. Ссылаясь на устаревшие списки избирателей, которые не признавали раскола партии, и конфликты собрания со съездом Советов, правительство большевиков и левых эсеров приняло решение о роспуске Учредительного собрания в январе 1918 года. Проект Декрета о роспуске Учредительного собрания был издан Центральным Исполнительным Комитетом Советского Союза , комитетом, в котором доминировал Ленин, ранее поддерживавший многопартийную систему свободных выборов. После поражения большевиков Ленин начал называть собрание «обманчивой формой буржуазно-демократического парламентаризма». [126] Некоторые утверждали, что это было началом развития авангардизма как иерархической партийной элиты, которая контролирует общество, [127] что привело к расколу между анархизмом и марксизмом , а ленинский коммунизм занял доминирующее положение на протяжении большей части 20-го века, исключив конкурирующие социалистические течения. [128]

Другие коммунисты и марксисты, особенно социал-демократы , выступавшие за развитие либеральной демократии как предпосылки социализма , с самого начала критиковали большевиков из-за того, что Россия считалась слишком отсталой для социалистической революции . [24] Советский коммунизм и левый коммунизм , вдохновлённые Немецкой революцией 1918–1919 годов и широкой пролетарской революционной волной, возникли в ответ на события в России и критикуют самопровозглашённые конституционно социалистические государства . Некоторые левые партии, такие как Социалистическая партия Великобритании , хвастались тем, что называли большевиков и, в более широком смысле, те коммунистические государства , которые либо следовали, либо были вдохновлены советской большевистской моделью развития, установлением государственного капитализма в конце 1917 года, как это будет описано в 20 веке несколькими учёными, экономистами и другими учёными, [48] или командной экономикой . [129] [130] [131] До того, как советский путь развития стал известен как социализм , в отношении двухэтапной теории , коммунисты не делали серьезных различий между социалистическим способом производства и коммунизмом; [83] это согласуется с ранними концепциями социализма, в которых закон стоимости больше не направляет экономическую деятельность, и помогало их формировать. Денежные отношения в форме меновой стоимости , прибыли , процента и наемного труда не будут действовать и применяться к марксистскому социализму. [26]

В то время как Иосиф Сталин заявил, что закон стоимости по-прежнему будет применяться к социализму и что Советский Союз был социалистическим согласно этому новому определению, которому следовали другие коммунистические лидеры, многие другие коммунисты придерживаются первоначального определения и заявляют, что коммунистические государства никогда не устанавливали социализм в этом смысле. Ленин описал свою политику как государственный капитализм, но считал ее необходимой для развития социализма, который, по словам левых критиков, никогда не был установлен, в то время как некоторые марксисты-ленинцы утверждают, что он был установлен только в эпоху Сталина и Мао , а затем стал капиталистическим государством, управляемым ревизионистами ; другие утверждают, что маоистский Китай всегда был государственно-капиталистическим, и поддерживают Народную Социалистическую Республику Албанию как единственное социалистическое государство после Советского Союза при Сталине, [132] [133] которое первым заявило, что достигло социализма с помощью Конституции Советского Союза 1936 года . [134]

Военный коммунизм был первой системой, принятой большевиками во время Гражданской войны в России в результате многочисленных проблем. [135] Несмотря на коммунизм в названии, он не имел ничего общего с коммунизмом, со строгой дисциплиной для рабочих, запрещенными забастовками , обязательной трудовой повинностью и контролем в военном стиле, и был описан как простой авторитарный контроль большевиков для сохранения власти и контроля в советских регионах, а не как какая-либо последовательная политическая идеология . [136] Советский Союз был создан в 1922 году. До широкого запрета в 1921 году в Коммунистической партии было несколько фракций, наиболее заметными из которых были Левая оппозиция , Правая оппозиция и Рабочая оппозиция , которые спорили о пути развития, которому следует следовать. Левая и рабочая оппозиции были более критичны к государственно-капиталистическому развитию, а рабочая в частности критиковала бюрократизацию и развитие сверху, в то время как Правая оппозиция больше поддерживала государственно-капиталистическое развитие и выступала за новую экономическую политику . [135] Следуя демократическому централизму Ленина , ленинские партии были организованы на иерархической основе, с активными ячейками членов в качестве широкой базы. Они состояли только из элитных кадров, одобренных высшими членами партии как надежные и полностью подчиненные партийной дисциплине . [137] Троцкизм обогнал левых коммунистов как главное диссидентское коммунистическое течение, в то время как более либертарные коммунизмы , восходящие к либертарианскому марксистскому течению советского коммунизма, оставались важными диссидентскими коммунизмами за пределами Советского Союза. Следуя демократическому централизму Ленина , ленинские партии были организованы на иерархической основе, с активными ячейками членов в качестве широкой базы. Они состояли только из элитных кадров, одобренных высшими членами партии как надежные и полностью подчиненные партийной дисциплине . Великая чистка 1936–1938 годов была попыткой Иосифа Сталина уничтожить любую возможную оппозицию внутри Коммунистической партии Советского Союза . На московских процессах были осуждены многие старые большевики, сыгравшие видную роль во время русской революции или в советском правительстве Ленина впоследствии, в том числе Лев Каменев ,Григорий Зиновьев , Алексей Рыков и Николай Бухарин были обвинены, признаны виновными в заговоре против Советского Союза и были казнены. [138] [137]

Разрушения Второй мировой войны привели к масштабной программе восстановления, включающей восстановление промышленных предприятий, жилья и транспорта, а также демобилизацию и миграцию миллионов солдат и гражданских лиц. В разгар этих потрясений зимой 1946–1947 годов Советский Союз пережил самый страшный естественный голод в 20 веке. [139] Не было серьезного сопротивления Сталину, поскольку тайная полиция продолжала отправлять возможных подозреваемых в ГУЛАГ . Отношения с Соединенными Штатами и Великобританией изменились с дружеских на враждебные, поскольку они осудили политический контроль Сталина над Восточной Европой и его блокаду Берлина . К 1947 году началась холодная война . Сам Сталин считал, что капитализм — это пустая оболочка, которая рухнет под возросшим невоенным давлением, оказываемым через доверенных лиц в таких странах, как Италия. Он сильно недооценил экономическую мощь Запада и вместо триумфа увидел, как Запад создает альянсы, которые были призваны навсегда остановить или сдержать советскую экспансию. В начале 1950 года Сталин дал добро на вторжение Северной Кореи в Южную Корею , ожидая короткой войны. Он был ошеломлен, когда американцы вошли и разгромили северокорейцев, поставив их почти на советскую границу. Сталин поддержал вступление Китая в Корейскую войну , что отбросило американцев к довоенным границам, но усилило напряженность. Соединенные Штаты решили мобилизовать свою экономику для длительного противостояния с Советами, создали водородную бомбу и укрепили альянс НАТО , который охватывал Западную Европу . [140]

По словам Горлицкого и Хлевнюка, последовательной и первостепенной целью Сталина после 1945 года было укрепление статуса сверхдержавы страны и, несмотря на растущую физическую дряхлость, сохранение своей собственной власти. Сталин создал систему руководства, которая отражала исторические царские стили патернализма и репрессий, но при этом была вполне современной. Наверху личная преданность Сталину имела решающее значение. Сталин также создал мощные комитеты, повысил молодых специалистов и начал крупные институциональные инновации. Несмотря на преследования, заместители Сталина культивировали неформальные нормы и взаимопонимание, которые легли в основу коллективного правления после его смерти. [139]

Для большинства жителей Запада и антикоммунистически настроенных россиян Сталин рассматривается исключительно негативно как массовый убийца ; для значительного числа россиян и грузин он считается великим государственным деятелем и строителем государства. [141]

После гражданской войны в Китае Мао Цзэдун и Коммунистическая партия Китая пришли к власти в 1949 году, когда националистическое правительство во главе с Гоминьданом бежало на остров Тайвань. В 1950–1953 годах Китай вел крупномасштабную необъявленную войну с Соединенными Штатами, Южной Кореей и силами Организации Объединенных Наций в Корейской войне . Хотя война закончилась военным тупиком, она дала Мао возможность выявить и очистить элементы в Китае, которые, казалось, поддерживали капитализм. Сначала было тесное сотрудничество со Сталиным, который отправлял технических экспертов для помощи процессу индустриализации по линии советской модели 1930-х годов. [142] После смерти Сталина в 1953 году отношения с Москвой испортились — Мао считал, что преемники Сталина предали коммунистический идеал. Мао обвинил советского лидера Никиту Хрущева в том, что он был лидером «ревизионистской клики», которая выступила против марксизма и ленинизма и теперь готовила почву для реставрации капитализма. [143] К 1960 году обе страны оказались на острие меча. Обе страны начали заключать союзы со сторонниками коммунистов по всему миру, тем самым разделив мировое движение на два враждебных лагеря. [144]

Отвергнув советскую модель быстрой урбанизации, Мао Цзэдун и его главный помощник Дэн Сяопин начали Большой скачок в 1957–1961 годах с целью индустриализации Китая в одночасье, используя крестьянские деревни в качестве базы, а не крупные города. [145] Частная собственность на землю закончилась, и крестьяне работали в крупных коллективных хозяйствах, которым теперь было приказано запустить операции тяжелой промышленности, такие как сталелитейные заводы. Заводы строились в отдаленных местах из-за нехватки технических специалистов, менеджеров, транспорта или необходимых объектов. Индустриализация провалилась, и главным результатом стал резкий неожиданный спад сельскохозяйственного производства, что привело к массовому голоду и миллионам смертей. Годы Большого скачка фактически стали свидетелями экономического регресса, причем 1958–1961 годы были единственными годами между 1953 и 1983 годами, когда экономика Китая пережила отрицательный рост. Политический экономист Дуайт Перкинс утверждает: «Огромные объемы инвестиций привели лишь к скромному росту производства или вообще не привели к нему. ... Короче говоря, «Большой скачок» был очень дорогой катастрофой». [146] Поставленный во главе спасения экономики, Дэн принял прагматичную политику, которая не нравилась идеалисту Мао. Некоторое время Мао находился в тени, но вернулся на центральную сцену и очистил Дэна и его союзников в ходе Культурной революции (1966–1976). [147]

Культурная революция была потрясением, направленным на интеллектуалов и лидеров партии с 1966 по 1976 год. Целью Мао было очистить коммунизм, устранив прокапиталистов и традиционалистов путем навязывания маоистской ортодоксальности внутри Коммунистической партии Китая . Движение парализовало Китай политически и ослабило страну экономически, культурно и интеллектуально на долгие годы. Миллионы людей были обвинены, унижены, лишены власти и либо заключены в тюрьму, либо убиты, либо, что чаще всего, отправлены на работу в качестве сельскохозяйственных рабочих. Мао настаивал на том, чтобы те, кого он называл ревизионистами, были устранены путем жестокой классовой борьбы . Двумя наиболее выдающимися активистами были маршал Линь Бяо из армии и жена Мао Цзян Цин . Молодежь Китая ответила на призыв Мао, сформировав отряды Красной гвардии по всей стране. Движение распространилось на армию, городских рабочих и само руководство Коммунистической партии. Это привело к широкомасштабной фракционной борьбе во всех слоях общества. В высшем руководстве это привело к массовой чистке высокопоставленных чиновников, обвиняемых в принятии « капиталистического пути », в первую очередь Лю Шаоци и Дэн Сяопина . В тот же период культ личности Мао достиг огромных размеров. После смерти Мао в 1976 году выжившие были реабилитированы, и многие вернулись к власти. [148] [ нужна страница ]

Правительство Мао несет ответственность за огромное количество смертей, по оценкам от 40 до 80 миллионов жертв из-за голода, преследований, тюремного труда и массовых казней. [149] [150] [151] [152] Мао также хвалят за то, что он превратил Китай из полуколонии в ведущую мировую державу с значительно развитой грамотностью, правами женщин, базовым здравоохранением, начальным образованием и продолжительностью жизни. [153] [154] [155] [156]

Его ведущая роль во Второй мировой войне привела к появлению индустриального Советского Союза как сверхдержавы . [157] [158] Марксистско-ленинские правительства, смоделированные по образцу Советского Союза, пришли к власти с советской помощью в Болгарии , Чехословакии , Восточной Германии , Польше , Венгрии и Румынии . Марксистско-ленинское правительство было также создано при Иосипе Броз Тито в Югославии ; независимая политика Тито привела к расколу Тито и Сталина и исключению Югославии из Коминформа в 1948 году, а титизм был заклеймен как уклонистский . Албания также стала независимым марксистско-ленинским государством после албано-советского раскола в 1960 году, [132] [133] в результате идеологического разногласия между Энвером Ходжой , сталинистом, и советским правительством Никиты Хрущева , который провел период десталинизации и возобновил дипломатические отношения с Югославией в 1976 году. [159] Коммунистическая партия Китая во главе с Мао Цзэдуном основала Китайскую Народную Республику , которая последовала своему собственному идеологическому пути развития после китайско-советского раскола . [160] Коммунизм рассматривался как соперник и угроза западному капитализму на протяжении большей части 20-го века. [161]

В Западной Европе коммунистические партии были частью нескольких послевоенных правительств, и даже когда Холодная война вынудила многие из этих стран отстранить их от правительства, как, например, в Италии, они оставались частью либерально-демократического процесса. [162] [163] Было также много событий в либертарианском марксизме, особенно в 1960-х годах с Новыми левыми . [164] К 1960-м и 1970-м годам многие западные коммунистические партии критиковали многие действия коммунистических государств, дистанцировались от них и разработали демократический путь к социализму , который стал известен как еврокоммунизм . [162] Это развитие критиковалось более ортодоксальными сторонниками Советского Союза как равнозначное социал-демократии . [165]

С 1957 года коммунисты часто приходили к власти в индийском штате Керала . [166]

В 1959 году кубинские коммунисты-революционеры свергли предыдущее правительство Кубы под руководством диктатора Фульхенсио Батисты . Лидер кубинской революции Фидель Кастро правил Кубой с 1959 по 2008 год. [167]

С падением Варшавского договора после революций 1989 года , что привело к падению большей части бывшего Восточного блока , Советский Союз был распущен 26 декабря 1991 года. Это стало результатом декларации № 142-Н Совета Республик Верховного Совета Советского Союза . [168] Декларация признала независимость бывших советских республик и создала Содружество Независимых Государств , хотя пять из подписавших ратифицировали ее гораздо позже или не сделали этого вообще. Накануне президент СССР Михаил Горбачев (восьмой и последний лидер Советского Союза ) ушел в отставку, объявил о прекращении своей деятельности и передал свои полномочия, включая контроль над Чегетом , президенту России Борису Ельцину . Тем же вечером в 7:32 советский флаг был спущен с Кремля в последний раз и заменен дореволюционным российским флагом . Ранее, с августа по декабрь 1991 года, все отдельные республики, включая саму Россию, вышли из союза. За неделю до официального роспуска союза одиннадцать республик подписали Алма-Атинский протокол , формально учредивший Содружество Независимых Государств , и объявили, что Советский Союз прекратил свое существование. [169] [170]

По состоянию на 2023 год, государства, контролируемые марксистско-ленинскими партиями в рамках однопартийной системы, включают Китайскую Народную Республику, Республику Куба , Лаосскую Народно-Демократическую Республику и Социалистическую Республику Вьетнам . [примечание 4] Коммунистические партии или их партии-потомки остаются политически важными в ряде других стран. С распадом Советского Союза и падением коммунизма произошел раскол между теми жесткими коммунистами, которых в СМИ иногда называют неосталинистами , которые остались приверженными ортодоксальному марксизму-ленинизму , и теми, кто, например, левые в Германии, работают в рамках либерально-демократического процесса для демократического пути к социализму; [171] другие правящие коммунистические партии стали ближе к демократическим социалистическим и социал-демократическим партиям. [172] За пределами коммунистических государств реформированные коммунистические партии возглавляли или были частью левых правительственных или региональных коалиций, в том числе в бывшем Восточном блоке. В Непале коммунисты ( КПН ОМЛ и Непальская коммунистическая партия ) были частью 1-го Непальского учредительного собрания , которое отменило монархию в 2008 году и превратило страну в федеральную либерально-демократическую республику, и демократически разделили власть с другими коммунистами, марксистами-ленинцами и маоистами ( КПН маоистская ), социал-демократами ( Непальский конгресс ) и другими в рамках их Народной многопартийной демократии . [173] [174] Коммунистическая партия Российской Федерации имеет некоторых сторонников, но является реформистской, а не революционной, стремясь уменьшить неравенство рыночной экономики России. [1]

Китайские экономические реформы начались в 1978 году под руководством Дэн Сяопина , и с тех пор Китаю удалось снизить уровень бедности с 53% в эпоху Мао до всего лишь 8% в 2001 году. [175] После потери советских субсидий и поддержки Вьетнам и Куба привлекли больше иностранных инвестиций в свои страны, а их экономики стали более ориентированными на рынок. [1] Северная Корея, последняя коммунистическая страна, которая все еще практикует коммунизм советского образца, является как репрессивной, так и изоляционистской. [1]

Коммунистическая политическая мысль и теория разнообразны, но имеют несколько основных элементов. [a] Доминирующие формы коммунизма основаны на марксизме или ленинизме , но существуют также немарксистские версии коммунизма, такие как анархо-коммунизм и христианский коммунизм , которые частично остаются под влиянием марксистских теорий, таких как либертарианский марксизм и гуманистический марксизм в частности. Общие элементы включают в себя теоретическую, а не идеологическую направленность, идентификацию политических партий не по идеологии, а по классовым и экономическим интересам, и идентификацию с пролетариатом. По мнению коммунистов, пролетариат может избежать массовой безработицы только в случае свержения капитализма; в краткосрочной перспективе ориентированные на государство коммунисты выступают за государственную собственность на командные высоты экономики как средство защиты пролетариата от капиталистического давления. Некоторые коммунисты отличаются от других марксистов тем, что видят в крестьянах и мелких собственниках возможных союзников в своей цели сокращения отмены капитализма. [177]

Для ленинского коммунизма такие цели, включая краткосрочные интересы пролетариата для улучшения их политических и материальных условий, могут быть достигнуты только посредством авангардизма , элитарной формы социализма сверху , которая опирается на теоретический анализ для определения интересов пролетариата, а не на консультации с самими пролетариями, [177] как это пропагандируют либертарианские коммунисты. [10] Когда они участвуют в выборах, главная задача ленинских коммунистов заключается в обучении избирателей тому, что считается их истинными интересами, а не в ответе на выражение интересов самими избирателями. Когда они получили контроль над государством, главная задача ленинских коммунистов заключалась в том, чтобы не дать другим политическим партиям обманывать пролетариат, например, выдвигая своих собственных независимых кандидатов. Этот авангардистский подход исходит из их приверженности демократическому централизму , в котором коммунисты могут быть только кадрами, т. е. членами партии, которые являются постоянными профессиональными революционерами, как это было задумано Владимиром Лениным . [177]

Марксизм — это метод социально-экономического анализа, который использует материалистическую интерпретацию исторического развития, более известную как исторический материализм , для понимания отношений социальных классов и социальных конфликтов , а также диалектическую перспективу для рассмотрения социальных преобразований . Он берет свое начало в работах немецких философов 19-го века Карла Маркса и Фридриха Энгельса . Поскольку марксизм со временем развился в различные ветви и школы мысли , не существует единой, окончательной марксистской теории . [178] Марксизм считает себя воплощением научного социализма , но не моделирует идеальное общество, основанное на замысле интеллектуалов , в результате чего коммунизм рассматривается как положение дел , которое должно быть установлено на основе какого-либо разумного замысла; скорее, это неидеалистическая попытка понимания материальной истории и общества, в результате чего коммунизм является выражением реального движения с параметрами, которые вытекают из реальной жизни. [179]

Согласно марксистской теории, классовый конфликт возникает в капиталистических обществах из-за противоречий между материальными интересами угнетенного и эксплуатируемого пролетариата — класса наемных рабочих, занятых производством товаров и услуг, — и буржуазии — правящего класса , владеющего средствами производства и извлекающего свое богатство путем присвоения прибавочного продукта , произведенного пролетариатом в форме прибыли . Эта классовая борьба, которая обычно выражается как восстание производительных сил общества против его производственных отношений , приводит к периоду краткосрочных кризисов, поскольку буржуазия борется за управление усиливающимся отчуждением труда, испытываемым пролетариатом, хотя и с различной степенью классового сознания . В периоды глубоких кризисов сопротивление угнетенных может достичь кульминации в пролетарской революции , которая, в случае победы, приводит к установлению социалистического способа производства, основанного на общественной собственности на средства производства, « Каждому по его вкладу », и производстве для использования . По мере того как производительные силы продолжали развиваться, коммунистическое общество , то есть бесклассовое, безгосударственное, гуманное общество, основанное на общей собственности , следует принципу « От каждого по способностям, каждому по потребностям ». [83]

Хотя он берет свое начало в работах Маркса и Энгельса, марксизм развился во множество различных ветвей и школ мысли, в результате чего в настоящее время не существует единой окончательной марксистской теории. [178] Различные марксистские школы делают больший акцент на определенных аспектах классического марксизма, отвергая или изменяя другие аспекты. Многие школы мысли стремились объединить марксистские концепции и немарксистские концепции, что затем привело к противоречивым выводам. [180] Существует движение к признанию того, что исторический материализм и диалектический материализм остаются основополагающими аспектами всех марксистских школ мысли . [95] Марксизм-ленинизм и его ответвления являются наиболее известными из них и были движущей силой в международных отношениях на протяжении большей части 20-го века. [181]

Классический марксизм — это экономические, философские и социологические теории, изложенные Марксом и Энгельсом в противопоставлении более поздним разработкам в марксизме, особенно ленинизму и марксизму-ленинизму. [182] Ортодоксальный марксизм — это корпус марксистской мысли, возникший после смерти Маркса и ставший официальной философией социалистического движения, представленного во Втором Интернационале до Первой мировой войны в 1914 году. Ортодоксальный марксизм стремится упростить, кодифицировать и систематизировать марксистский метод и теорию, проясняя воспринимаемые двусмысленности и противоречия классического марксизма. Философия ортодоксального марксизма включает в себя понимание того, что материальное развитие (прогресс в области технологий в производительных силах ) является основным агентом изменений в структуре общества и человеческих социальных отношений и что социальные системы и их отношения (например, феодализм , капитализм и т. д.) становятся противоречивыми и неэффективными по мере развития производительных сил, что приводит к некоторой форме социальной революции, возникающей в ответ на растущие противоречия. Это революционное изменение является средством для фундаментальных изменений в масштабах всего общества и в конечном итоге приводит к появлению новых экономических систем . [183] Как термин, ортодоксальный марксизм представляет собой методы исторического материализма и диалектического материализма, а не нормативные аспекты, присущие классическому марксизму, не подразумевая при этом догматической приверженности результатам исследований Маркса. [184]

В основе марксизма лежит исторический материализм, материалистическая концепция истории, которая утверждает, что ключевой характеристикой экономических систем на протяжении истории был способ производства и что смена способов производства была вызвана классовой борьбой. Согласно этому анализу, промышленная революция ввела мир в новый капиталистический способ производства . До капитализма некоторые рабочие классы имели собственность на орудия производства; однако, поскольку машины были намного более эффективными, эта собственность обесценилась, и большинство рабочих могли выжить, только продавая свой труд, чтобы использовать чужие машины и получать прибыль от кого-то другого. Соответственно, капитализм разделил мир между двумя основными классами, а именно пролетариатом и буржуазией . Эти классы являются прямо антагонистическими, поскольку последний обладает частной собственностью на средства производства , получая прибыль за счет прибавочной стоимости, произведенной пролетариатом, который не имеет собственности на средства производства и, следовательно, не имеет другого выбора, кроме как продавать свой труд буржуазии. [185]

Согласно материалистической концепции истории, именно посредством продвижения своих собственных материальных интересов восходящая буржуазия в рамках феодализма захватила власть и отменила из всех отношений частной собственности только феодальные привилегии, тем самым устранив феодальный правящий класс . Это был еще один ключевой элемент, лежащий в основе консолидации капитализма как нового способа производства, окончательного выражения классовых и имущественных отношений, которое привело к массовому расширению производства. Только при капитализме частная собственность сама по себе может быть отменена. [186] Аналогичным образом пролетариат захватил бы политическую власть, отменил бы буржуазную собственность посредством общей собственности на средства производства, тем самым упразднив буржуазию, в конечном итоге упразднив сам пролетариат и введя мир в коммунизм как новый способ производства . Между капитализмом и коммунизмом находится диктатура пролетариата ; это поражение буржуазного государства , но еще не капиталистического способа производства, и в то же время единственный элемент, который ставит в область возможности движение от этого способа производства. Эта диктатура , основанная на модели Парижской Коммуны , [187] должна быть самым демократическим государством, где вся государственная власть избирается и отзывается на основе всеобщего избирательного права . [188]

Критика политической экономии — это форма социальной критики , которая отвергает различные социальные категории и структуры, составляющие основной дискурс относительно форм и модальностей распределения ресурсов и распределения доходов в экономике. Коммунисты, такие как Маркс и Энгельс, описываются как выдающиеся критики политической экономии. [189] [190] [191] Критика отвергает использование экономистами того, что ее сторонники считают нереалистичными аксиомами , ошибочными историческими предположениями и нормативным использованием различных описательных повествований. [192] Они отвергают то, что они называют тенденцией основных экономистов постулировать экономику как априорную общественную категорию. [193] Те, кто занимается критикой экономики, склонны отвергать точку зрения, что экономику и ее категории следует понимать как нечто трансисторическое . [194] [195] Она рассматривается просто как один из многих типов исторически специфичных способов распределения ресурсов. Они утверждают, что это относительно новый способ распределения ресурсов, который появился вместе с современностью. [196] [197] [198]

Критики экономики критикуют данный статус самой экономики и не стремятся создавать теории относительно того, как управлять экономикой. [199] [200] Критики экономики обычно рассматривают то, что чаще всего называют экономикой, как совокупность метафизических концепций, а также общественных и нормативных практик, а не как результат каких-либо самоочевидных или провозглашенных экономических законов. [193] Они также склонны считать взгляды, которые являются общепринятыми в области экономики, ошибочными или просто псевдонаукой . [201] [202] В 21 веке существует множество критических замечаний в отношении политической экономии; общим для них является критика того, что критики политической экономии склонны рассматривать как догму , т. е. утверждений об экономике как необходимой и трансисторической общественной категории. [203]

Марксистская экономика и ее сторонники рассматривают капитализм как экономически неустойчивый и неспособный улучшить уровень жизни населения из-за необходимости компенсировать падение нормы прибыли путем сокращения заработной платы работников, социальных льгот и осуществления военной агрессии. Коммунистический способ производства придет на смену капитализму как новый способ производства человечества через рабочую революцию . Согласно марксистской теории кризиса , коммунизм — это не неизбежность, а экономическая необходимость. [204]

Важной концепцией в марксизме является социализация, т. е. общественная собственность , против национализации . Национализация — это государственная собственность на собственность, тогда как социализация — это контроль и управление собственностью со стороны общества. Марксизм рассматривает последнее как свою цель и считает национализацию тактическим вопросом, поскольку государственная собственность все еще находится в сфере капиталистического способа производства . По словам Фридриха Энгельса , «превращение ... в государственную собственность не устраняет капиталистическую природу производительных сил. ... Государственная собственность на производительные силы не является решением конфликта, но в ней скрыты технические условия, которые образуют элементы этого решения». [b] Это привело к тому, что марксистские группы и тенденции, критикующие советскую модель, стали называть государства, основанные на национализации, такие как Советский Союз, государственно-капиталистическими , точку зрения, которую также разделяют несколько ученых. [48] [129] [131]

Прежде всего, он установит демократическую конституцию и посредством этого — прямое или косвенное господство пролетариата.

В то время как марксисты предлагают заменить буржуазное государство пролетарским полугосударством посредством революции ( диктатура пролетариата ), которое в конечном итоге отомрет, анархисты предупреждают, что государство должно быть отменено вместе с капитализмом. Тем не менее, желаемые конечные результаты, безгосударственное, коммунальное общество , остаются теми же. [216]

Карл Маркс критиковал либерализм как недостаточно демократический и считал, что неравное социальное положение рабочих во время промышленной революции подрывало демократическую деятельность граждан. [217] Марксисты расходятся в своих позициях по отношению к демократии. [218] [219]

Некоторые утверждают, что демократическое принятие решений, соответствующее марксизму, должно включать голосование по вопросу о том, как следует организовать избыточный труд . [221]Сегодня споры о наследии Маркса в основном вращаются вокруг его неоднозначного отношения к демократии.

— Роберт Мейстер [220]

Мы хотим достичь нового и лучшего общественного порядка: в этом новом и лучшем обществе не должно быть ни богатых, ни бедных; все должны будут работать. Не горстка богатых людей, а все трудящиеся должны пользоваться плодами своего общего труда. Машины и другие усовершенствования должны служить облегчению труда всех, а не давать возможность немногим обогащаться за счет миллионов и десятков миллионов людей. Это новое и лучшее общество называется социалистическим обществом. Учения об этом обществе называются «социализмом».

Владимир Ленин, К сельской бедноте (1903) [222]

Ленинизм — политическая идеология, разработанная русским марксистом- революционером Владимиром Лениным , которая предлагает установление диктатуры пролетариата во главе с революционной авангардной партией в качестве политической прелюдии к установлению коммунизма. Функция ленинской авангардной партии — обеспечить рабочий класс политическим сознанием (образованием и организацией) и революционным руководством, необходимыми для свержения капитализма в Российской империи (1721–1917). [223]

Ленинское революционное руководство основано на «Манифесте Коммунистической партии» (1848), определяющем Коммунистическую партию как «наиболее передовую и решительную часть рабочих партий каждой страны; ту часть, которая толкает вперед все остальные». Как авангардная партия, большевики рассматривали историю через теоретические рамки диалектического материализма , который санкционировал политическую приверженность успешному свержению капитализма, а затем установлению социализма ; и как революционное национальное правительство, для осуществления социально-экономического перехода всеми средствами. [224] [ необходима полная цитата ]

Марксизм-ленинизм — политическая идеология, разработанная Иосифом Сталиным . [225] По словам его сторонников, он основан на марксизме и ленинизме . Он описывает конкретную политическую идеологию, которую Сталин реализовал в Коммунистической партии Советского Союза и в глобальном масштабе в Коминтерне . Между историками нет определенного согласия относительно того, действительно ли Сталин следовал принципам Маркса и Ленина. [226] Он также содержит аспекты, которые, по мнению некоторых, являются отклонениями от марксизма, такими как социализм в одной стране . [227] [228] Марксизм-ленинизм был официальной идеологией коммунистических партий 20-го века (включая троцкистскую ) и был разработан после смерти Ленина; его тремя принципами были диалектический материализм , ведущая роль коммунистической партии через демократический централизм и плановая экономика с индустриализацией и коллективизацией сельского хозяйства . Марксизм-ленинизм вводит в заблуждение, потому что Маркс и Ленин никогда не санкционировали и не поддерживали создание -изма после них, и показателен, потому что, популяризированный после смерти Ленина Сталиным, он содержал те три доктринальных и институционализированных принципа, которые стали моделью для более поздних режимов советского типа; его глобальное влияние, охватившее на пике своего развития по меньшей мере треть населения мира, сделало марксизм-ленинизм удобным ярлыком для коммунистического блока как динамичного идеологического порядка. [229] [c]

Во время Холодной войны марксизм-ленинизм был идеологией наиболее ярко выраженного коммунистического движения и является наиболее заметной идеологией, связанной с коммунизмом. [181] [примечание 8] Социал-фашизм был теорией, поддерживаемой Коминтерном и связанными с ним коммунистическими партиями в начале 1930-х годов, которая считала, что социал-демократия является вариантом фашизма , поскольку она стоит на пути диктатуры пролетариата , в дополнение к общей корпоративистской экономической модели. [231] В то время лидеры Коминтерна, такие как Сталин и Раджани Пальме Датт , заявляли, что капиталистическое общество вступило в Третий период , в котором пролетарская революция неизбежна, но может быть предотвращена социал-демократами и другими фашистскими силами. [231] [232] Термин «социал-фашист» использовался уничижительно для описания социал-демократических партий, антикоминтерновских и прогрессивных социалистических партий и диссидентов в филиалах Коминтерна в течение всего межвоенного периода . Теория социал-фашизма громко пропагандировалась Коммунистической партией Германии , которая в значительной степени контролировалась и финансировалась советским руководством с 1928 года. [232]

В марксизме-ленинизме антиревизионизм — это позиция, которая возникла в 1950-х годах в противовес реформам и хрущевской оттепели советского лидера Никиты Хрущева . В то время как Хрущев следовал интерпретации, которая отличалась от интерпретации Сталина, антиревизионисты в международном коммунистическом движении оставались преданными идеологическому наследию Сталина и критиковали Советский Союз при Хрущеве и его преемниках как государственно-капиталистический и социал-империалистический из-за его надежд на достижение мира с Соединенными Штатами. Термин сталинизм также используется для описания этих позиций, но часто не используется его сторонниками, которые полагают, что Сталин практиковал ортодоксальный марксизм и ленинизм. Поскольку различные политические течения прослеживают исторические корни ревизионизма в разных эпохах и лидерах, сегодня существуют значительные разногласия относительно того, что представляет собой антиревизионизм. Современные группы, которые называют себя антиревизионистами, делятся на несколько категорий. Некоторые поддерживают труды Сталина и Мао Цзэдуна, а некоторые — труды Сталина, отвергая Мао и в целом склоняясь к оппозиции троцкизму . Другие отвергают и Сталина, и Мао, прослеживая их идеологические корни до Маркса и Ленина. Кроме того, другие группы поддерживают различных менее известных исторических лидеров, таких как Энвер Ходжа , который также порвал с Мао во время китайско-албанского раскола . [132] [133] Социальный империализм был термином, который Мао использовал для критики Советского Союза после Сталина. Мао заявил, что Советский Союз сам стал империалистической державой, сохраняя социалистический фасад . [233] Ходжа согласился с Мао в этом анализе, прежде чем позже использовать это выражение, чтобы также осудить теорию трех миров Мао . [234]

Сталинизм представляет собой стиль правления Сталина в противоположность марксизму-ленинизму, социально-экономической системе и политической идеологии, реализованной Сталиным в Советском Союзе, а затем адаптированной другими государствами на основе идеологической советской модели , такой как централизованное планирование , национализация и однопартийное государство, наряду с общественной собственностью на средства производства , ускоренной индустриализацией , активным развитием производительных сил общества (научные исследования и разработки) и национализированными природными ресурсами . Марксизм-ленинизм сохранился после десталинизации , тогда как сталинизм — нет. В последних письмах перед смертью Ленин предупреждал об опасности личности Сталина и призывал советское правительство заменить его. [95] До смерти Иосифа Сталина в 1953 году советская коммунистическая партия называла свою собственную идеологию марксизмом-ленинизмом-сталинизмом . [177]

Марксизм-ленинизм подвергался критике со стороны других коммунистических и марксистских течений, которые заявляют, что марксистско-ленинские государства установили не социализм, а государственный капитализм . [48] [129] [131] Согласно марксизму, диктатура пролетариата представляет собой власть большинства (демократию), а не одной партии, в той мере, в какой один из основателей марксизма Фридрих Энгельс описал ее «специфическую форму» как демократическую республику . [235] По мнению Энгельса, государственная собственность сама по себе является частной собственностью капиталистической природы, [b] если только пролетариат не контролирует политическую власть, в этом случае она образует общественную собственность. [e] Вопрос о том, действительно ли пролетариат контролировал марксистско-ленинские государства, является предметом спора между марксизмом-ленинизмом и другими коммунистическими течениями. Для этих тенденций марксизм-ленинизм не является ни марксизмом, ни ленинизмом, ни объединением того и другого, а скорее искусственным термином, созданным для оправдания идеологического искажения Сталина, [236] навязанного Коммунистической партии Советского Союза и Коминтерну. В Советском Союзе эта борьба против марксизма-ленинизма была представлена троцкизмом , который называет себя марксистской и ленинской тенденцией. [237]

Троцкизм, разработанный Львом Троцким в противовес сталинизму , [238] является марксистской и ленинской тенденцией, которая поддерживает теорию перманентной революции и мировой революции, а не двухэтапную теорию и сталинский социализм в одной стране . Она поддерживала еще одну коммунистическую революцию в Советском Союзе и пролетарский интернационализм . [239]

Вместо того, чтобы представлять диктатуру пролетариата , Троцкий утверждал, что Советский Союз стал выродившимся рабочим государством под руководством Сталина, в котором классовые отношения возродились в новой форме. Политика Троцкого резко отличалась от политики Сталина и Мао, что наиболее важно в провозглашении необходимости международной пролетарской революции — а не социализма в одной стране — и поддержки истинной диктатуры пролетариата, основанной на демократических принципах. Борясь со Сталиным за власть в Советском Союзе, Троцкий и его сторонники организовались в Левую оппозицию , [240] платформа которой стала известна как троцкизм. [238]

В частности, Троцкий выступал за децентрализованную форму экономического планирования , [241] массовую советскую демократизацию , [242] выборное представительство советских социалистических партий , [243] [244] тактику единого фронта против крайне правых партий, [245] культурную автономию художественных движений, [246] добровольную коллективизацию , [247] [248] переходную программу [ 249] и социалистический интернационализм . [250]

Троцкий пользовался поддержкой многих партийных интеллектуалов , но это было затмено огромным аппаратом, который включал ГПУ и партийные кадры, находившиеся в распоряжении Сталина. [251] Сталину в конечном итоге удалось получить контроль над советским режимом, и попытки троцкистов отстранить Сталина от власти привели к изгнанию Троцкого из Советского Союза в 1929 году. Находясь в изгнании, Троцкий продолжил свою кампанию против Сталина, основав в 1938 году Четвертый Интернационал , троцкистского соперника Коминтерна. [252] [253] [254] В августе 1940 года Троцкий был убит в Мехико по приказу Сталина. Троцкистские течения включают ортодоксальный троцкизм , третий лагерь , посадизм и паблоизм . [255] [256]

Экономическая платформа плановой экономики в сочетании с подлинной рабочей демократией , изначально отстаиваемой Троцким, составила программу Четвертого Интернационала и современного троцкистского движения. [257]

Маоизм — это теория, вытекающая из учений китайского политического лидера Мао Цзэдуна . Разрабатывавшаяся с 1950-х годов до китайской экономической реформы Дэн Сяопина в 1970-х годах, она широко применялась в качестве руководящей политической и военной идеологии Коммунистической партии Китая и в качестве теории, направляющей революционные движения по всему миру. Ключевое отличие маоизма от других форм марксизма-ленинизма заключается в том, что крестьяне должны быть оплотом революционной энергии, руководимой рабочим классом. [258] Три общие маоистские ценности — это революционный популизм , практичность и диалектика . [259]

Синтез марксизма-ленинизма-маоизма, [f] который строится на двух отдельных теориях как китайская адаптация марксизма-ленинизма, не произошел при жизни Мао. После десталинизации марксизм-ленинизм сохранился в Советском Союзе , в то время как определенные антиревизионистские тенденции, такие как ходжаизм и маоизм, заявили, что они отклонились от своей первоначальной концепции. Иная политика применялась в Албании и Китае, которые стали более дистанцированными от Советского Союза. С 1960-х годов группы, которые называли себя маоистами , или те, кто поддерживал маоизм, не были объединены вокруг общего понимания маоизма, вместо этого имея свои собственные особые интерпретации политических, философских, экономических и военных трудов Мао. Его приверженцы утверждают, что как единая, последовательная высшая стадия марксизма она не была консолидирована до 1980-х годов, впервые оформленная « Сияющим путем» в 1982 году. [260] Благодаря опыту народной войны, которую вела партия, «Сияющий путь» смог позиционировать маоизм как новейшее развитие марксизма. [260]

Еврокоммунизм был ревизионистским течением в 1970-х и 1980-х годах в различных западноевропейских коммунистических партиях, утверждая, что разрабатывает теорию и практику социальных преобразований, более соответствующих их региону. Особенно заметные в Французской коммунистической партии , Итальянской коммунистической партии и Коммунистической партии Испании , коммунисты такого рода стремились подорвать влияние Советского Союза и его Всесоюзной коммунистической партии (большевиков) во время холодной войны . [162] Еврокоммунисты, как правило, имели большую привязанность к свободе и демократии, чем их марксистско-ленинские коллеги. [261] Энрико Берлингуэр , генеральный секретарь крупнейшей итальянской коммунистической партии, широко считался отцом еврокоммунизма. [262]

Либертарианский марксизм — это широкий спектр экономических и политических философий, которые подчеркивают антиавторитарные аспекты марксизма . Ранние течения либертарианский марксизм, известные как левый коммунизм , [263] возникли в оппозиции к марксизму-ленинизму [264] и его производным, таким как сталинизм и маоизм , а также троцкизму . [265] Либертарианский марксизм также критикует реформистские позиции, такие как позиции социал-демократов . [266] Либертарианский марксистские течения часто опираются на поздние работы Маркса и Энгельса, в частности, на « Грундриссе» и «Гражданскую войну во Франции» , [267] подчеркивая марксистскую веру в способность рабочего класса ковать свою собственную судьбу без необходимости в посредничестве или помощи революционной партии или государства в его освобождении. [268] Наряду с анархизмом , либертарианский марксизм является одним из основных производных либертарианского социализма . [269]

Помимо левого коммунизма, либертарианский марксизм включает в себя такие течения, как автономизм , коммунизация , коммунизм советов , де Леонизм , тенденция Джонсона-Фореста , леттризм , люксембургизм , ситуационизм , социализм или варварство , солидарность , мировое социалистическое движение и воркеризм , а также части фрейдомарксизма и новых левых . [270] Более того, либертарианский марксизм часто оказывал сильное влияние как на постлевых, так и на социальных анархистов . Известными теоретиками либертарианского марксизма были Антони Паннекук , Рая Дунаевская , Корнелиус Касториадис , Морис Бринтон , Даниэль Герен и Янис Варуфакис , [271] последний из которых утверждает, что сам Маркс был либертарианским марксистом. [272]

Советский коммунизм — это движение, возникшее в Германии и Нидерландах в 1920-х годах, [273] основной организацией которого была Коммунистическая рабочая партия Германии . Оно продолжается и сегодня как теоретическая и активистская позиция как в либертарианском марксизме , так и в либертарианском социализме . [274] Основной принцип советского коммунизма заключается в том, что правительство и экономика должны управляться рабочими советами , которые состоят из делегатов , избираемых на рабочих местах и отзываемых в любой момент. Советские коммунисты выступают против воспринимаемой авторитарной и недемократической природы централизованного планирования и государственного социализма , называемого государственным капитализмом , и идеи революционной партии, [275] [276], поскольку советские коммунисты считают, что революция, возглавляемая партией, обязательно приведет к партийной диктатуре . Советские коммунисты поддерживают рабочую демократию, созданную посредством федерации рабочих советов.

В отличие от социал-демократии и ленинского коммунизма, центральный аргумент коммунизма советов заключается в том, что демократические рабочие советы, возникающие на фабриках и в муниципалитетах, являются естественными формами организаций рабочего класса и правительственной власти. [277] [278] Эта точка зрения противоречит как реформистской [279], так и ленинской коммунистической идеологии, [275] которые соответственно подчеркивают парламентское и институциональное управление путем применения социальных реформ, с одной стороны, и авангардные партии и партисипативный демократический централизм , с другой. [279] [275]

Левый коммунизм — это ряд коммунистических взглядов, которых придерживаются коммунистические левые, которые критикуют политические идеи и практику, поддерживаемые, особенно после серии революций, положивших конец Первой мировой войне , проведенных большевиками и социал-демократами . [280] Левые коммунисты отстаивают позиции, которые они считают более подлинно марксистскими и пролетарскими , чем взгляды марксизма-ленинизма, поддерживаемые Коммунистическим Интернационалом после его первого конгресса (март 1919 г.) и во время его второго конгресса (июль–август 1920 г.). [264] [281] [282]

Левые коммунисты представляют собой ряд политических движений, отличных от марксистов-ленинцев , которых они в значительной степени рассматривают просто как левое крыло капитала , от анархо-коммунистов , некоторых из которых они считают интернационалистскими социалистами , и от различных других революционных социалистических течений, таких как де леонисты , которых они склонны рассматривать как интернационалистских социалистов только в ограниченных случаях. [283] Бордигизм — ленинское левокоммунистическое течение, названное в честь Амадео Бордиги , которого описывали как «большего ленинца, чем Ленин», и который считал себя ленинцем. [284]

Анархо-коммунизм — либертарианская теория анархизма и коммунизма, которая выступает за отмену государства , частной собственности и капитализма в пользу общего владения средствами производства ; [285] [286] прямую демократию ; и горизонтальную сеть добровольных объединений и рабочих советов с производством и потреблением, основанными на руководящем принципе: « От каждого по способностям, каждому по потребностям ». [287] [288] Анархо-коммунизм отличается от марксизма тем, что отвергает его точку зрения о необходимости фазы государственного социализма до установления коммунизма. Петр Кропоткин , главный теоретик анархо-коммунизма, утверждал, что революционное общество должно «немедленно трансформироваться в коммунистическое общество», что оно должно немедленно перейти к тому, что Маркс считал «более продвинутой, завершенной фазой коммунизма». [289] Таким образом, он пытается избежать повторного появления классовых различий и необходимости контроля со стороны государства. [289]

Некоторые формы анархо-коммунизма, такие как повстанческий анархизм , являются эгоистичными и находятся под сильным влиянием радикального индивидуализма , [290] [291] [292] полагая, что анархо-коммунизм вообще не требует коммунитарной природы. Большинство анархо-коммунистов рассматривают анархо-коммунизм как способ примирения оппозиции между личностью и обществом. [g] [293] [294]

Христианский коммунизм — это теологическая и политическая теория, основанная на представлении о том, что учения Иисуса Христа заставляют христиан поддерживать религиозный коммунизм как идеальную социальную систему . [53] Хотя нет всеобщего согласия относительно точных дат возникновения коммунистических идей и практик в христианстве, многие христиане-коммунисты утверждают, что свидетельства из Библии предполагают, что первые христиане, включая Апостолов в Новом Завете , основали свое собственное небольшое коммунистическое общество в годы после смерти и воскресения Иисуса. [295]

Многие сторонники христианского коммунизма утверждают, что ему учил Иисус и его практиковали сами апостолы, [296] аргумент, с которым историки и другие, включая антрополога Романа А. Монтеро, [297] такие ученые, как Эрнест Ренан , [298] [299] и теологи, как Чарльз Элликотт и Дональд Гатри , [300] [301] в целом согласны. [53] [302] Христианский коммунизм пользуется некоторой поддержкой в России. Российский музыкант Егор Летов был откровенным христианским коммунистом, и в интервью 1995 года он сказал: «Коммунизм — это Царство Божие на Земле». [303]

Эмили Моррис из Университетского колледжа Лондона писала, что, поскольку труды Карла Маркса вдохновили многие движения, включая Русскую революцию 1917 года , коммунизм «обычно путают с политической и экономической системой, которая развилась в Советском Союзе» после революции. [72] [h] Моррис также писала, что коммунизм в советском стиле «не «работал»» из-за «чрезмерно централизованной, репрессивной, бюрократической и жесткой экономической и политической системы». [72] Историк Анджей Пачковский резюмировал коммунизм как «идеологию, которая казалась явно противоположной, которая была основана на светском желании человечества достичь равенства и социальной справедливости и которая обещала большой скачок вперед к свободе». [60] Напротив, австрийско-американский экономист Людвиг фон Мизес утверждал, что, отменив свободные рынки, коммунистические чиновники не будут иметь ценовую систему, необходимую для руководства их плановым производством. [304]

Anti-communism developed as soon as communism became a conscious political movement in the 19th century, and anti-communist mass killings have been reported against alleged communists, or their alleged supporters, which were committed by anti-communists and political organizations or governments opposed to communism. The communist movement has faced opposition since it was founded and the opposition to it has often been organized and violent. Many of these anti-communist mass killing campaigns, primarily during the Cold War,[305][306] were supported by the United States and its Western Bloc allies,[307][308] including those who were formally part of the Non-Aligned Movement, such as the Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66 and Operation Condor in South America.[309][310]

Many authors have written about excess deaths under Communist states and mortality rates,[note 5] such as excess mortality in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin.[note 6] Some authors posit that there is a Communist death toll, whose death estimates vary widely, depending on the definitions of the deaths that are included in them, ranging from lows of 10–20 million to highs over 100 million. The higher estimates have been criticized by several scholars as ideologically motivated and inflated; they are also criticized for being inaccurate due to incomplete data, inflated by counting any excess death, making an unwarranted link to communism, and the grouping and body-counting itself. Higher estimates account for actions that Communist governments committed against civilians, including executions, human-made famines, and deaths that occurred during, or resulted from, imprisonment, and forced deportations and labor. Higher estimates are criticized for being based on sparse and incomplete data when significant errors are inevitable, and for being skewed to higher possible values.[59] Others have argued that, while certain estimates may not be accurate, "quibbling about numbers is unseemly. What matters is that many, many people were killed by communist regimes."[50] Historian Mark Bradley wrote that while the exact numbers have been in dispute, the order of magnitude is not.[311]

There is no consensus among genocide scholars and scholars of Communism about whether some or all the events constituted a genocide or mass killing.[note 9] Among genocide scholars, there is no consensus on a common terminology,[319] and the events have been variously referred to as excess mortality or mass deaths; other terms used to define some of such killings include classicide, crimes against humanity, democide, genocide, politicide, holocaust, mass killing, and repression.[58][note 10] These scholars state that most Communist states did not engage in mass killings;[324][note 11] Benjamin Valentino proposes the category of Communist mass killing, alongside colonial, counter-guerrilla, and ethnic mass killing, as a subtype of dispossessive mass killing to distinguish it from coercive mass killing.[329] Genocide scholars do not consider ideology,[321] or regime-type, as an important factor that explains mass killings.[330] Some authors, such as John Gray,[331] Daniel Goldhagen,[332] and Richard Pipes,[333] consider the ideology of communism to be a significant causative factor in mass killings. Some connect killings in Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union, Mao Zedong's China, and Pol Pot's Cambodia on the basis that Stalin influenced Mao, who influenced Pol Pot; in all cases, scholars say killings were carried out as part of a policy of an unbalanced modernization process of rapid industrialization.[58][note 12] Daniel Goldhagen argues that 20th century communist regimes "have killed more people than any other regime type."[335]