Бенгальский ( / b ɛ n ˈ ɡ ɔː l / ben- GAWL ; [1] [2] Бенгальский : বঙ্গ , латинизированный : Bôṅgo , произносится [ˈbɔŋgo] ) —исторический географический,этнолингвистическийи культурный термин, обозначающий регион ввосточной частииндийскогосубконтинентау вершиныБенгальского залива. Регион собственно Бенгалии разделен между современным суверенным государствомБангладешииндийским штатомЗападнаяБенгалия.

Древнее королевство Ванга широко считается тезкой региона Бенгалия. [3] Бенгальский календарь восходит к правлению Шашанки в 7 веке н. э. Империя Пала была основана в Бенгалии в 8 веке. Династии Сена и Дева правили между 11 и 13 веками. К 14 веку Бенгалия была поглощена мусульманскими завоеваниями на индийском субконтиненте . Был образован независимый Бенгальский султанат , который стал восточной границей исламского мира . [4] [5] [6] В этот период правление и влияние Бенгалии распространились на Ассам, Аракан , Трипуру, Бихар и Ориссу. [7] [8] Бенгальский субах позже стал процветающей частью империи Великих Моголов .

Последний независимый наваб Бенгалии был побежден в 1757 году в битве при Плесси Ост-Индской компанией . Бенгальское президентство компании превратилось в крупнейшую административную единицу Британской Индии со столицей как Бенгалии, так и Индии до 1911 года. В результате первого раздела Бенгалии недолго просуществовавшая провинция под названием Восточная Бенгалия и Ассам существовала между 1905 и 1911 годами со столицей в бывшей столице Великих Моголов Дакке . После референдума в Силхете и голосований Законодательного совета Бенгалии и Законодательного собрания Бенгалии регион был снова разделен по религиозному признаку в 1947 году .

Бенгальская культура, особенно ее литература , музыка , искусство и кино, хорошо известны в Южной Азии и за ее пределами. Регион также известен своими экономическими и социальными учеными, среди которых несколько лауреатов Нобелевской премии . Когда-то здесь был город с самым высоким уровнем дохода на душу населения в Британской Индии, [9] сегодня регион является лидером в Южной Азии по гендерному паритету , гендерному разрыву в оплате труда и другим показателям человеческого развития . [10] [11] [12] [13] [14]

Название Бенгалия происходит от древнего королевства Ванга (произносится как Бонго), [15] [16] самые ранние записи о котором относятся к эпосу Махабхарата в первом тысячелетии до н . э . [16] Ссылка на «Вангалам» присутствует в надписи в храме Брихадишвара в Танджавуре , которая является одной из старейших ссылок на Бенгалию. [17] Термин Вангаладеша используется для описания региона в южноиндийских записях XI века. [18] [19] [20] Современный термин Бангла известен с XIV века, когда был основан Бенгальский султанат , первый правитель которого Шамсуддин Ильяс Шах был известен как Шах Бангалы . [21] Португальцы называли регион Бенгалой в эпоху Великих географических открытий . [ 22]

.jpg/440px-Vanga_coin_(400-300_BCE).jpg)

Неолитические стоянки были найдены в нескольких частях региона. [23] Во втором тысячелетии до нашей эры в регионе были обнаружены сообщества, занимающиеся выращиванием риса. К одиннадцатому веку до нашей эры люди в Бенгалии жили в систематически выровненных домах, производили медные предметы и изготавливали черную и красную керамику. Остатки поселений медного века находятся в регионе. [24] С наступлением железного века люди в Бенгалии переняли железное оружие, инструменты и ирригационное оборудование. [25] С 600 года до нашей эры вторая волна урбанизации охватила северный индийский субконтинент как часть культуры северной черной полированной керамики . Появились древние археологические памятники и города в Дихаре , Панду Раджар Дхиби , Махастхангархе , Чандракетугархе и Вари-Батешваре . Реки Ганг , Брахмапутра и Мегхна были естественными артериями для сообщения и транспортировки. [26] Устья рек Бенгальского залива позволяли вести морскую торговлю с отдаленными странами Юго-Восточной Азии и другими странами. [26]

Древние геополитические подразделения Бенгалии включали Варендра , Сухма , Анга , Ванга , Саматата и Харикела . Эти регионы часто были независимыми или находились под властью более крупных империй. Надпись Махастхан Брахми указывает, что Бенгалия находилась под властью империи Маурьев в 3 веке до н. э. [27] Надпись представляла собой административный приказ, предписывающий помощь бедствующей части населения. [27] Монеты с чеканкой, найденные в регионе, указывают на то, что монеты использовались в качестве валюты во время железного века. [28] [29] Тезка Бенгалии — древнее королевство Ванга, которое имело репутацию морской державы с заморскими колониями. Принц из Бенгалии по имени Виджая основал первое королевство на Шри-Ланке . Две самые выдающиеся паниндийские империи этого периода включали империю Маурьев и империю Гуптов . Этот регион был центром художественной, политической, социальной, духовной и научной мысли, включая изобретение шахмат , индийских цифр и концепции нуля . [30]

Регион был известен древним грекам и римлянам как Гангаридай . [31] Греческий посол Мегасфен записал его военную мощь и господство в дельте Ганга . Армия вторжения Александра Македонского была остановлена рассказами о мощи Гангаридай в 325 г. до н. э., включая кавалерию боевых слонов . Более поздние римские отчеты отметили морские торговые пути с Бенгалией. Римские монеты 1-го века с изображениями Геракла были найдены в регионе и указывают на торговые связи с римским Египтом через Красное море . [32] Руины Вари-Батешвара , как полагают, являются эмпориумом (торговым центром) Соунагуры, упомянутым римским географом Клавдием Птолемеем . [33] [34] Римская амфора была найдена в районе Пурба Мединипур в Западной Бенгалии, которая была изготовлена в Элане (современная Акаба, Иордания ) между 4-м и 7-м веками нашей эры. [35]

.jpg/440px-Pañcarakṣā_(Cambridge_University_Library_MS_Add.1688).jpg)

Первое объединенное бенгальское государство можно проследить до правления Шашанки . Истоки бенгальского календаря можно проследить до его правления. Шашанка основал королевство Гауда . После смерти Шашанки Бенгалия пережила период гражданской войны, известный как Матсьяньям. [36] Древний город Гауда позже дал начало империи Пала . Первый император Пала Гопала I был избран собранием вождей в Гауде. Королевство Пала превратилось в одну из крупнейших империй на индийском субконтиненте. Период Пала ознаменовался достижениями в лингвистике, скульптуре, живописи и образовании. Империя достигла наибольшего территориального расширения при Дхармапале и Девапале . Палы соперничали за контроль над Каннауджем с соперничающими династиями Гурджара-Пратихара и Раштракута . Влияние Пала также распространилось на Тибет и Суматру из-за путешествий и проповедей Атиши . Университет Наланды был основан Палами. Они также построили Сомапура Махавихара , который был крупнейшим монастырским учреждением на субконтиненте. Правление Палов в конечном итоге распалось. Династия Чандра правила юго-восточной Бенгалией и Араканом . Династия Варман правила частями северо-восточной Бенгалии и Ассама . Династия Сена появилась как главный преемник Палов к 11 веку. Сены были возрождающейся индуистской династией, которая правила большей частью Бенгалии. Меньшая династия Дэва также правила частями региона. Древние китайские посетители, такие как Сюаньцзан, предоставили подробные отчеты о городах и монастырских учреждениях Бенгалии. [37]

Мусульманская торговля с Бенгалией расцвела после падения Сасанидской империи и захвата арабами персидских торговых путей. Большая часть этой торговли происходила с юго-восточной Бенгалией в районах к востоку от реки Мегхна . Бенгалия, вероятно, использовалась как транзитный путь в Китай первыми мусульманами. Монеты Аббасидов были обнаружены в археологических руинах Пахарпура и Майнамати . [38] Коллекция монет Сасанидов, Омейядов и Аббасидов хранится в Национальном музее Бангладеш . [39]

В 1204 году генерал Гуридов Мухаммад бин Бахтияр Хальджи начал исламское завоевание Бенгалии. [40] Падение Лакхнаути было описано историками около 1243 года. Лакхнаути был столицей династии Сена. Согласно историческим свидетельствам, кавалерия Гуридов пронеслась через равнины Ганга в сторону Бенгалии. Они вошли в бенгальскую столицу, замаскированные под торговцев лошадьми. Оказавшись внутри королевского комплекса, Бахтияр и его всадники быстро одолели охранников короля Сена, которые только что сели есть. Затем король поспешно бежал в лес со своими последователями. [41] Свержение короля Сены было описано как государственный переворот, который «открыл эпоху, длившуюся более пяти столетий, в течение которой большая часть Бенгалии находилась под властью правителей, исповедовавших исламскую веру. Само по себе это не было исключением, поскольку примерно с этого времени и до восемнадцатого века мусульманские правители правили большей частью индийского субконтинента. Однако исключительным было то, что среди внутренних провинций Индии только в Бенгалии — регионе, примерно равном по размеру Англии и Шотландии вместе взятым — большинство коренного населения приняло религию правящего класса, ислам». [41] Бенгалия стала провинцией Делийского султаната . Была выпущена монета с изображением всадника в честь мусульманского завоевания Лакхнаути с надписями на санскрите и арабском языке. Неудавшееся исламское вторжение в Тибет также было организовано Бахтияром. Бенгалия находилась под формальным правлением Делийского султаната примерно 150 лет. Дели боролся за консолидацию контроля над Бенгалией. Мятежные губернаторы часто стремились к утверждению автономии или независимости. Султан Илтутмиш восстановил контроль над Бенгалией в 1225 году после подавления мятежников. Из-за значительного расстояния по суше власть Дели в Бенгалии была относительно слабой. Местным губернаторам оставалось расширять территорию и приводить новые районы под власть мусульман, например, посредством завоевания Силхета в 1303 году.

В 1338 году в трех главных городах Бенгалии вспыхнули новые восстания. Губернаторы Лакхнаути, Сатгаона и Сонаргаона объявили независимость от Дели. Это позволило правителю Сонаргаона Факхруддину Мубараку Шаху присоединить Читтагонг к исламской администрации. К 1352 году правитель Сатгаона Шамсуддин Ильяс Шах объединил регион в независимое государство. Ильяс Шах основал свою столицу в Пандуа . [42] Новое отколовшееся государство возникло как Бенгальский султанат , который превратился в территориальную, торговую и морскую империю. В то время исламский мир простирался от мусульманской Испании на западе до Бенгалии на востоке.

Первые набеги Ильяс-шаха привели к тому, что первая мусульманская армия вошла в Непал и протянулась от Варанаси на западе до Ориссы на юге и Ассама на востоке. [43] Делийская армия продолжала отбиваться от новой бенгальской армии. Бенгало-Делийская война закончилась в 1359 году, когда Дели признал независимость Бенгалии. Сын Ильяс-шаха Сикандар-шах победил делийского султана Фируз-шаха Туглука во время осады форта Экдала. Последующий мирный договор признал независимость Бенгалии, и Сикандар-шах получил в дар от султана Дели золотую корону. [44] Правитель Аракана искал убежища в Бенгалии во время правления Гиясуддина Азама-шаха . Джалалуддин Мухаммад-шах позже помог араканскому королю восстановить контроль над своим троном в обмен на то, чтобы стать государством-данником Бенгальского султаната. Бенгальское влияние в Аракане сохранялось в течение 300 лет. [45] Бенгалия также помогла королю Трипуры вернуть себе контроль над троном в обмен на то, что он стал государством-данником. Правитель султаната Джаунпур также искал убежища в Бенгалии. [46] Вассальные государства Бенгалии включали Аракан, Трипуру, Чандрадвип и Пратапгарх . На пике своего развития территория Бенгальского султаната включала части Аракана, Ассама, Бихара, Ориссы и Трипуры. [7] Бенгальский султанат добился наибольшего военного успеха при Алауддине Хуссейне Шахе , который был провозглашен завоевателем Ассама после того, как его войска во главе с шахом Исмаилом Гази свергли династию Кхен и аннексировали большую часть Ассама. В морской торговле Бенгальский султанат извлекал выгоду из торговых сетей Индийского океана и стал центром реэкспорта . Жираф был привезен африканскими посланниками из Малинди ко двору Бенгалии и позже был подарен императорскому Китаю . Торговцы, владеющие судами, выступали в качестве посланников султана во время путешествий в различные регионы Азии и Африки. Многие богатые бенгальские торговцы жили в Малакке. [47] Бенгальские корабли перевозили посольства из Брунея , Ачеха и Малакки в Китай. Бенгалия и Мальдивы вели обширную торговлю ракушками в качестве валюты . [48] Султан Бенгалии пожертвовал средства на строительство школ в регионе Хиджаз в Аравии.[49]

Пять династических периодов Бенгальского султаната охватывали период от династии Ильяс-Шахи до периода правления бенгальских новообращенных, династии Хуссейн-Шахи , периода правления абиссинских узурпаторов; перерыва династией Сури ; и закончились династией Каррани . Битва при Радж-Махале и пленение Дауд-хана Каррани ознаменовали конец Бенгальского султаната во время правления императора Великих Моголов Акбара . В конце 16-го века конфедерация под названием Баро-Бхуян сопротивлялась вторжениям Моголов в восточную Бенгалию. В Баро-Бхуян входили двенадцать мусульманских и индуистских лидеров заминдаров Бенгалии . Их возглавлял Иса-хан , бывший премьер-министр Бенгальского султаната. К 17-му веку Моголы смогли полностью включить регион в свою империю.

Могольская Бенгалия имела самую богатую элиту и была самым богатым регионом на субконтиненте. Торговля и богатство Бенгалии так впечатлили Моголов, что императоры Моголов описывали ее как Рай Наций . [ 50] Новая провинциальная столица была построена в Дакке . Члены императорской семьи были назначены на должности в Могольской Бенгалии, включая должность губернатора ( субедара ). Дакка стала центром дворцовых интриг и политики. Некоторые из самых выдающихся губернаторов включали раджпутского генерала Ман Сингха I , сына императора Шах-Джахана принца Шах Шуджу , сына императора Аурангзеба и позже императора Моголов Азам-шаха , и влиятельного аристократа Шайста-хана . Во время правления Шайста-хана португальцы и араканцы были изгнаны из порта Читтагонг в 1666 году. Бенгалия стала восточной границей администрации Моголов. К XVIII веку Бенгалия стала домом для полунезависимой аристократии во главе с навабами Бенгалии . [51] Бенгальский премьер Муршид Кули Хан сумел ограничить влияние губернатора из-за его соперничества с принцем Азам Шахом. Хан контролировал финансы Бенгалии, поскольку отвечал за казну. Он перенес столицу провинции из Дакки в Муршидабад .

-1.jpg/440px-Khas_Mahal_(Agra_Fort)-1.jpg)

В 1717 году двор Моголов в Дели признал наследственную монархию наваба Бенгалии. Правитель был официально назван «навабом Бенгалии, Бихара и Ориссы », поскольку наваб правил тремя регионами на восточном субконтиненте. Навабы начали выпускать собственные монеты, но продолжали номинально присягать императору Моголов. Богатство Бенгалии было жизненно важно для двора Моголов, поскольку Дели получал наибольшую долю доходов от двора наваба. Навабы руководили периодом беспрецедентного экономического роста и процветания, включая эпоху растущей организации в текстильной промышленности, банковском деле, военно-промышленном комплексе, производстве высококачественных ремесленных изделий и других отраслях. Процесс протоиндустриализации был в самом разгаре. При навабах улицы бенгальских городов были заполнены брокерами, рабочими, пеонами, наибами, вакилями и обычными торговцами. [52] Государство наваба было крупным экспортером бенгальского муслина , шелка, пороха и селитры . Навабы также разрешали европейским торговым компаниям работать в Бенгалии, включая Британскую Ост-Индскую компанию , Французскую Ост-Индскую компанию , Датскую Ост-Индскую компанию , Австрийскую Ост-Индскую компанию , Остендескую компанию и Голландскую Ост-Индскую компанию . Навабы также с подозрением относились к растущему влиянию этих компаний.

.jpg/440px-Krishna_traveling_to_Mathura_(Bengal_painting).jpg)

Во времена правления Моголов Бенгалия была центром мировой торговли муслином и шелком. В эпоху Моголов самым важным центром производства хлопка была Бенгалия, особенно вокруг ее столицы Дакки, что привело к тому, что муслин называли «дака» на отдаленных рынках, таких как Центральная Азия. [53] Внутри страны большая часть Индии зависела от бенгальских продуктов, таких как рис, шелк и хлопчатобумажные ткани. За рубежом европейцы зависели от бенгальских продуктов, таких как хлопчатобумажные ткани, шелка и опиум; например, на Бенгалию приходилось 40% голландского импорта из Азии, включая более 50% текстиля и около 80% шелка. [54] Из Бенгалии селитра также отправлялась в Европу, опиум продавался в Индонезии , сырой шелк экспортировался в Японию и Нидерланды, хлопок и шелковые ткани экспортировались в Европу, Индонезию и Японию, [55] хлопчатобумажная ткань экспортировалась в Америку и Индийский океан. [56] В Бенгалии также была крупная судостроительная промышленность. Что касается тоннажа судостроения в XVI–XVIII веках, то экономический историк Индраджит Рей оценивает годовой объем производства Бенгалии в 223 250 тонн по сравнению с 23 061 тоннами, произведенными в девятнадцати колониях Северной Америки с 1769 по 1771 год. [57]

Начиная с XVI века европейские торговцы пересекали морские пути в Бенгалию после завоевания португальцами Малакки и Гоа. Португальцы основали поселение в Читтагонге с разрешения Бенгальского султаната в 1528 году, но позже были изгнаны Моголами в 1666 году. В XVIII веке двор Моголов быстро распался из-за вторжения Надир-шаха и внутренних восстаний, что позволило европейским колониальным державам создать торговые посты по всей территории. Британская Ост-Индская компания в конечном итоге стала ведущей военной силой в регионе; и победила последнего независимого наваба Бенгалии в битве при Плесси в 1757 году. [51]

Британская Ост-Индская компания начала влиять и контролировать наваба Бенгалии с 1757 года после битвы при Плесси, тем самым ознаменовав начало британского влияния в Индии. Британский контроль над Бенгалией усилился между 1757 и 1793 годами, в то время как наваб был сведен к марионеточной фигуре. [58] с президентством Форт-Уильяма , утверждающим больший контроль над всей провинцией Бенгалия и соседними территориями. Калькутта была названа столицей британских территорий в Индии в 1772 году. Президентство управлялось военно-гражданской администрацией, включая Бенгальскую армию , и имело шестую самую раннюю в мире железнодорожную сеть. Между 1833 и 1854 годами губернатор Бенгалии был одновременно генерал-губернатором Индии в течение многих лет. Великий Бенгальский голод случался несколько раз во время колониального правления (в частности, Великий Бенгальский голод 1770 года и Бенгальский голод 1943 года ). [59] [60] Под британским правлением Бенгалия пережила деиндустриализацию своей доколониальной экономики. [61]

Политика компании привела к деиндустриализации текстильной промышленности Бенгалии. [62] Капитал, накопленный Ост-Индской компанией в Бенгалии, был инвестирован в начинающуюся промышленную революцию в Великобритании , в такие отрасли, как текстильное производство . [61] [63] Неэффективное экономическое управление, наряду с засухой и эпидемией оспы, напрямую привело к голоду в Большой Бенгалии 1770 года, который, по оценкам, стал причиной смерти от 1 до 10 миллионов человек. [64] [65] [66] [67]

В 1862 году был создан Законодательный совет Бенгалии как первый современный законодательный орган в Индии . Выборное представительство постепенно вводилось в начале 20-го века, в том числе с реформами Морли-Минто и системой двоевластия . В 1937 году совет стал верхней палатой законодательного органа Бенгалии, в то время как была создана Законодательная ассамблея Бенгалии . В период с 1937 по 1947 год главой исполнительной власти правительства был премьер-министр Бенгалии .

Бенгальское президентство было крупнейшей административной единицей в Британской империи . На пике своего развития оно охватывало большую часть современных Индии, Пакистана, Бангладеш, Бирмы, Малайзии и Сингапура. В 1830 году Британские поселения Стрейтс на побережье Малаккского пролива стали резиденцией Бенгалии. В эту область входили бывший остров Принца Уэльского , провинция Уэллсли , Малакка и Сингапур . [68] В 1867 году Пенанг , Сингапур и Малакка были отделены от Бенгалии в Стрейтс-Сетлментс . [68] Британская Бирма стала провинцией Индии, а позднее и колонией Короны . Западные районы, включая Уступленные и Завоёванные провинции и Пенджаб , были дополнительно реорганизованы. Северо-восточные районы стали колониальным Ассамом .

В 1876 году около 200 000 человек погибли в Бенгалии в результате Большого циклона Бакергандж 1876 года в регионе Барисал . [69] Около 50 миллионов человек погибли в Бенгалии из-за массовых вспышек чумы и голода, которые произошли в 1895-1920 годах, в основном в Западной Бенгалии. [70]

Индийское восстание 1857 года началось на окраине Калькутты и распространилось на Дакку, Читтагонг, Джалпайгури, Силхет и Агарталу в знак солидарности с восстаниями в Северной Индии. Провал восстания привел к отмене правления компании в Индии и установлению прямого правления британцами над Индией, обычно называемого британским владычеством . Бенгальский ренессанс конца 19-го и начала 20-го века оказал большое влияние на культурную и экономическую жизнь Бенгалии и положил начало большому прогрессу в литературе и науке Бенгалии. Между 1905 и 1911 годами была предпринята неудачная попытка разделить провинцию Бенгалия на две части: собственно Бенгалию и недолго просуществовавшую провинцию Восточная Бенгалия и Ассам , где была основана Всеиндийская мусульманская лига . [71] В 1911 году бенгальский поэт и эрудит Рабиндранат Тагор стал первым в Азии лауреатом Нобелевской премии, получив Нобелевскую премию по литературе .

Бенгалия сыграла важную роль в движении за независимость Индии , в котором доминировали революционные группы . Вооруженные попытки свергнуть британское владычество начались с восстания Титумира и достигли кульминации, когда Субхас Чандра Бос возглавил Индийскую национальную армию против британцев. Бенгалия также играла центральную роль в растущем политическом сознании мусульманского населения — в 1906 году в Дакке была создана Всеиндийская мусульманская лига. Движение за мусульманскую родину боролось за суверенное государство в восточной Индии с помощью Лахорской резолюции в 1943 году. Индуистский национализм также был силен в Бенгалии, которая была домом для таких групп, как Хинду Махасабха . Несмотря на отчаянные усилия политиков Хусейна Шахида Сухраварди и Сарата Чандры Боса сформировать Объединенную Бенгалию , [72] когда Индия обрела независимость в 1947 году, Бенгалия была разделена по религиозным признакам. [73] Западная часть присоединилась к Индии (и была названа Западной Бенгалией), а восточная часть присоединилась к Пакистану как провинция под названием Восточная Бенгалия (позже переименованная в Восточный Пакистан , что дало начало Бангладеш в 1971 году). Обстоятельства раздела были кровавыми, с широко распространенными религиозными беспорядками в Бенгалии. [73] [74]

27 апреля 1947 года последний премьер-министр Бенгалии Хусейн Шахид Сухраварди провел пресс-конференцию в Нью-Дели, где изложил свое видение независимой Бенгалии. Сухраварди сказал: «Давайте остановимся на мгновение, чтобы подумать, какой может быть Бенгалия, если она останется единой. Это будет великая страна, действительно самая богатая и процветающая в Индии, способная дать своему народу высокий уровень жизни, где великий народ сможет подняться до самой полной высоты своего роста, земля, которая будет действительно изобильной. Она будет богата сельским хозяйством, промышленностью и торговлей, и со временем она станет одним из могущественных и прогрессивных государств мира. Если Бенгалия останется единой, это будет не мечта, не фантазия». [75] 2 июня 1947 года премьер-министр Великобритании Клемент Эттли сказал послу США в Соединенном Королевстве , что существует «явная возможность того, что Бенгалия может решить против раздела и против присоединения либо к Индостану, либо к Пакистану». [76]

3 июня 1947 года план Маунтбеттена наметил раздел Британской Индии . 20 июня Законодательное собрание Бенгалии собралось, чтобы принять решение о разделе Бенгалии. На предварительном совместном заседании было решено (126 голосов против 90), что если провинция останется единой, она должна присоединиться к Учредительному собранию Пакистана . На отдельном заседании законодателей из Западной Бенгалии было решено (58 голосов против 21), что провинция должна быть разделена, а Западная Бенгалия должна присоединиться к Учредительному собранию Индии . На другом заседании законодателей из Восточной Бенгалии было решено (106 голосов против 35), что провинция не должна быть разделена и (107 голосов против 34), что Восточная Бенгалия должна присоединиться к Учредительному собранию Пакистана , если Бенгалия будет разделена. [77] 6 июля округ Силхет в Ассаме проголосовал на референдуме за присоединение к Восточной Бенгалии .

Английскому адвокату Сирилу Рэдклиффу было поручено провести границы Пакистана и Индии. Линия Рэдклиффа создала границу между Доминионом Индия и Доминионом Пакистан , которая позже стала границей Бангладеш-Индия . Линия Рэдклиффа присудила две трети Бенгалии в качестве восточного крыла Пакистана, хотя исторические бенгальские столицы Гаур , Пандуа , Муршидабад и Калькутта находились на индийской стороне, недалеко от границы с Пакистаном. Статус Дакки как столицы также был восстановлен.

Большая часть региона Бенгалия лежит в дельте Ганга-Брахмапутры , но на севере, северо-востоке и юго-востоке есть возвышенности. Дельта Ганга возникает в результате слияния рек Ганг , Брахмапутра и Мегхна и их притоков. Общая площадь Бенгалии составляет 237 212 квадратных километров (91 588 квадратных миль) — Западная Бенгалия составляет 88 752 км 2 (34 267 квадратных миль), а Бангладеш — 148 460 км 2 (57 321 квадратных миль).

Плоская и плодородная Бангладешская равнина доминирует в географии Бангладеш . Читтагонгский горный массив и регион Силхет являются домом для большинства гор в Бангладеш . Большая часть Бангладеш находится в пределах 10 метров (33 футов) над уровнем моря, и считается, что около 10% земли будет затоплено, если уровень моря поднимется на 1 метр (3,3 фута). [78] Из-за этой низкой высоты большая часть этого региона исключительно уязвима для сезонных наводнений из-за муссонов. Самая высокая точка в Бангладеш находится в хребте Моудок на высоте 1052 метра (3451 фут). [79] Большая часть береговой линии включает в себя болотистые джунгли , Сундарбан , крупнейший мангровый лес в мире и дом для разнообразной флоры и фауны, включая королевского бенгальского тигра . В 1997 году этот регион был объявлен находящимся под угрозой исчезновения. [80]

Западная Бенгалия находится на восточном горлышке Индии, простираясь от Гималаев на севере до Бенгальского залива на юге. Общая площадь штата составляет 88 752 км 2 (34 267 кв. миль). [81] Горный регион Дарджилинг-Гималай на северной оконечности штата относится к восточным Гималаям. В этом регионе находится Сандакфу (3636 м (11 929 футов)) — самая высокая вершина штата. [82] Узкий регион Тераи отделяет этот регион от равнин, которые, в свою очередь, переходят в дельту Ганга на юге. Регион Рарх находится между дельтой Ганга на востоке и западным плато и возвышенностями . Небольшой прибрежный регион находится на крайнем юге, в то время как мангровые леса Сундарбана образуют замечательную географическую достопримечательность в дельте Ганга.

По меньшей мере в девяти округах Западной Бенгалии и 42 округах Бангладеш уровень мышьяка в грунтовых водах превышает максимально допустимый уровень Всемирной организации здравоохранения в 50 мкг/л или 50 частей на миллиард, а неочищенная вода непригодна для потребления человеком. [83] Вода вызывает арсеникоз, рак кожи и различные другие осложнения в организме.

Северная Бенгалия — это термин, используемый для северо-западной части Бангладеш и северной части Западной Бенгалии. Бангладешская часть включает округ Раджшахи и округ Рангпур . Как правило, это область, лежащая к западу от реки Джамуна и к северу от реки Падма , и включает тракт Баринд . Политически часть Западной Бенгалии включает округ Джалпайгури и большую часть округа Малда (за исключением округа Муршидабад ) вместе, а части Бихара включают округ Кишангандж . Холмы Дарджилинг также являются частью Северной Бенгалии. Жители Джайпайгури, Алипурдуара и Куч-Бехара обычно называют себя северными бенгальцами. Северная Бенгалия разделена на регионы Тераи и Дуарс . Северная Бенгалия также известна своим богатым культурным наследием, включая два объекта Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО. Помимо бенгальского большинства, Северная Бенгалия является домом для многих других общин, включая непальцев, санталов , лепчха и раджбонгши.

Северо-Восточная Бенгалия [84] относится к региону Силхет, который сегодня включает в себя округ Силхет Бангладеш и округ Каримгандж в индийском штате Ассам . Регион славится своей плодородной землей, множеством рек, обширными чайными плантациями, тропическими лесами и водно-болотными угодьями. Реки Брахмапутра и Барак являются географическими маркерами этого района. Город Силхет является его крупнейшим городским центром, а регион известен своим уникальным региональным языком силхети . Древнее название региона - Шрихатта и Насратшахи. [85] Регион находился под властью королевств Камарупа и Харикела , а также Бенгальского султаната . Позже он стал районом Империи Великих Моголов . Наряду с преобладающим бенгальским населением проживают небольшие племена гаро , бишнуприя манипури , кхасия и другие племенные меньшинства. [85]

Регион находится на перекрестке Бенгалии и северо-восточной Индии .

Центральная Бенгалия относится к округу Дакка в Бангладеш. Она включает возвышенный участок Мадхупур с большим лесом деревьев сал . Река Падма пересекает южную часть региона, разделяя большой регион Фаридпур . На севере лежат большие регионы Мименсингх и Тангайл .

Южная Бенгалия охватывает юго-запад Бангладеш и южную часть индийского штата Западная Бенгалия. Бангладешская часть включает округ Кхулна , округ Барисал и предлагаемый округ Фаридпур. [86] Часть Южной Бенгалии Западной Бенгалии включает округ Президентства , округ Бурдван и округ Мединипур . [87] [88] [89]

Сундарбан , крупнейший очаг биоразнообразия , находится в Южной Бенгалии. 60% лесов находится в Бангладеш, а остальная часть — в Индии .

Юго-Восточная Бенгалия [90] [91] [92] относится к холмисто-прибрежным читтагоноязычным и прибрежным бенгалоязычным районам округа Читтагонг на юго-востоке Бангладеш. Регион известен своим талассократическим и мореходным наследием. В древности в этом районе доминировали бенгальские королевства Харикела и Саматата . Арабским торговцам он был известен как Самандар в IX веке. [93] В средневековый период регионом управляли династия Чандра , Бенгальский султанат , Королевство Трипура , Королевство Мраук У , Португальская империя и Империя Великих Моголов до прихода британского правления. Читтагонный язык , родственный бенгали, распространен в прибрежных районах юго-восточной Бенгалии. Наряду с бенгальским населением здесь также проживают тибето-бирманские этнические группы, в том числе народы чакма , марма , танчангья и баум .

Юго-Восточная Бенгалия считается мостом в Юго-Восточную Азию, а северные части Аракана также исторически считаются ее частью. [94]

There are four World Heritage Sites in the region, including the Sundarbans, the Somapura Mahavihara, the Mosque City of Bagerhat and the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. Other prominent places include the Bishnupur, Bankura temple city, the Adina Mosque, the Caravanserai Mosque, numerous zamindar palaces (like Ahsan Manzil and Cooch Behar Palace), the Lalbagh Fort, the Great Caravanserai ruins, the Shaista Khan Caravanserai ruins, the Kolkata Victoria Memorial, the Dhaka Parliament Building, archaeologically excavated ancient fort cities in Mahasthangarh, Mainamati, Chandraketugarh and Wari-Bateshwar, the Jaldapara National Park, the Lawachara National Park, the Teknaf Game Reserve and the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

Cox's Bazar in southeastern Bangladesh is home to the longest natural sea beach in the world with an unbroken length of 120 km (75 mi). It is also a growing surfing destination.[95] St. Martin's Island, off the coast of Chittagong Division, is home to the sole coral reef in Bengal.

Bengal was a regional power of the Indian subcontinent. The administrative jurisdiction of Bengal historically extended beyond the territory of Bengal proper. In the 9th century, the Pala Empire of Bengal ruled large parts of northern India. The Bengal Sultanate controlled Bengal, Assam, Arakan, Bihar and Orissa at different periods in history. In Mughal Bengal, the Nawab of Bengal had a jurisdiction covering Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. Bengal's administrative jurisdiction reached its greatest extent under the British Empire, when the Bengal Presidency extended from the Straits of Malacca in the east to the Khyber Pass in the west. In the late-19th and early-20th centuries, administrative reorganisation drastically reduced the territory of Bengal.

Several regions bordering Bengal proper continue to have high levels of Bengali influence. The Indian state of Tripura has a Bengali majority population. Bengali influence is also prevalent in the Indian regions of Assam, Meghalaya, Bihar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands; as well as in Myanmar's Rakhine State.

Arakan (now Rakhine State, Myanmar) has historically been under strong Bengali influence. Since antiquity, Bengal has influenced the culture of Arakan. The ancient Bengali script was used in Arakan.[96] An Arakanese inscription recorded the reign of the Bengali Candra dynasty. Paul Wheatley described the "Indianization" of Arakan.[97]

According to Pamela Gutman, "Arakan was ruled by kings who adopted Indian titles and traditions to suit their own environment. Indian Brahmins conducted royal ceremonies, Buddhist monks spread their teachings, traders came and went and artists and architects used Indian models for inspiration. In the later period, there was also influence from the Islamic courts of Bengal and Delhi".[98] Arakan emerged as a vassal state of the Bengal Sultanate.[99] It later became an independent kingdom. The royal court and culture of the Kingdom of Mrauk U was heavily influenced by Bengal. Bengali Muslims served in the royal court as ministers and military commanders.[99] Bengali Hindus and Bengali Buddhists served as priests. Some of the most important poets of medieval Bengali literature lived in Arakan, including Alaol and Daulat Qazi.[100] In 1660, Prince Shah Shuja, the governor of Mughal Bengal and a pretender of the Peacock Throne of India, was forced to seek asylum in Arakan.[101][102] Bengali influence in the Arakanese royal court persisted until Burmese annexation in the 18th-century.

The modern-day Rohingya population is a legacy of Bengal's influence on Arakan.[103][100] The Rohingya genocide resulted in the displacement of over a million people between 2016 and 2017, with many being uprooted from their homes in Rakhine State.

The Indian state of Assam shares many cultural similarities with Bengal. The Assamese language uses the same script as the Bengali language. The Barak Valley has a Bengali-speaking majority population. During the Partition of India, Assam was also partitioned along with Bengal. The Sylhet Division joined East Bengal in Pakistan, with the exception of Karimganj which joined Indian Assam. Previously, East Bengal and Assam were part of a single province called Eastern Bengal and Assam between 1905 and 1912 under the British Raj.[104]

Assam and Bengal were often part of the same kingdoms, including Kamarupa, Gauda and Kamata. Large parts of Assam were annexed by Alauddin Hussain Shah during the Bengal Sultanate.[105] Assam was one of the few regions in the subcontinent to successfully resist Mughal expansion and never fell completely under Mughal rule.

Bengali is the most spoken language among the population of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a strategically important archipelago which is controlled by India as a federal territory. The islands were once used as a British penal colony. During World War II, the islands were seized by the Japanese and controlled by the Provisional Government of Free India. Anti-British leader Subhash Chandra Bose visited and renamed the islands. Between 1949 and 1971, the Indian government resettled many Bengali Hindus in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[106]

In antiquity, Bihar and Bengal were often part of the same kingdoms. The ancient region of Magadha covered both Bihar and Bengal. Magadha was the birthplace or bastion of several pan-Indian empires, including the Mauryan Empire, the Gupta Empire and the Pala Empire. Bengal, Bihar and Orissa together formed a single province under the Mughal Empire. The Nawab of Bengal was styled as the Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.[107]

The Chittagong Hill Tracts is the southeastern frontier of Bangladesh. Its indigenous population includes Tibeto-Burman ethnicities, including the Chakma people, Bawm people and Mro people among others. The region was historically ruled by tribal chieftains of the Chakma Circle and Bohmong Circle. In 1713, the Chakma Raja signed a treaty with Mughal Bengal after obtaining permission from Emperor Farrukhsiyar for trade with the plains of Chittagong.[108][109] Like the kings of Arakan, the Chakma Circle began to fashion themselves using Mughal nomenclatures and titles. They initially resisted the Permanent Settlement and the activities of the East India Company.[109] The tribal royal families of the region came under heavy Bengali influence. The Chakma queen Benita Roy was a friend of Rabindranath Tagore. The region was governed by the Chittagong Hill Tracts manual under colonial rule. The manual was significantly amended after the end of British rule; and the region became fully integrated with Bangladesh.[110]

Through trade, settlements and the exchange of ideas; parts of Maritime Southeast Asia became linked with Bengal.[111][112] Language, literature, art, governing systems, religions and philosophies in ancient Sumatra and Java were influenced by Bengal. Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms in Southeast Asia depended on the Bay of Bengal for trade and ideas. Islam in Southeast Asia also spread through the Bay of Bengal, which was a bridge between the Malay Archipelago and Indo-Islamic states of the Indian subcontinent.[113][114] A large number of wealthy merchants from Bengal were based in Malacca.[47] Bengali ships were the largest ships in the waters of the Malay Archipelago during the 15th century.[115]

Between 1830 and 1867, the ports of Singapore and Malacca, the island of Penang, and a portion of the Malay Peninsula were ruled under the jurisdiction of the Bengal Presidency of the British Empire.[116] These areas were known as the Straits Settlements, which was separated from the Bengal Presidency and converted into a Crown colony in 1867.[117]: 980

The Indian state of Meghalaya historically came under the influence of Shah Jalal, a Muslim missionary and conqueror from Sylhet. During British rule, the city of Shillong was the summer capital of Eastern Bengal and Assam (modern Bangladesh and Northeast India). Shillong boasted the highest per capita income in British India.[9]

..jpg/440px-Sepoy_of_the_Indian_Infantry,_1900_(c)..jpg)

The ancient Mauryan, Gupta and Pala empires of the Magadha region (Bihar and Bengal) extended into northern India. The westernmost border of the Bengal Sultanate extended towards Varanasi and Jaunpur.[118][46] In the 19th century, Punjab and the Ceded and Conquered Provinces formed the western extent of the Bengal Presidency. According to the British historian Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, "The Bengal Presidency, an administrative jurisdiction introduced by the East India Company, would later include not only the whole of northern India up to the Khyber Pass on the north-west frontier with Afghanistan, but would spread eastwards to Burma and Singapore as well".[119]

Odisha, previously known as Orissa, has a significant Bengali minority. Historically, the region has faced invasions from Bengal, including an invasion by Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah.[120] Parts of the region were ruled by the Bengal Sultanate and Mughal Bengal. The Nawab of Bengal was styled as the "Nawab of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa" because the Nawab was granted jurisdiction over Orissa by the Mughal Emperor.[107]

During the Pala dynasty, Tibet received missionaries from Bengal who influenced the emergence of Tibetan Buddhism.[121][122] One of the most notable missionaries was Atisa. During the 13th century, Tibet experienced an Islamic invasion by the forces of Bakhtiyar Khalji, the Muslim conqueror of Bengal.[123]

The princely state of Tripura was ruled by the Manikya dynasty until the 1949 Tripura Merger Agreement. Tripura was historically a vassal state of Bengal. After assuming the throne with military support from the Bengal Sultanate in 1464, Ratna Manikya I introduced administrative reforms inspired by the government of Bengal. The Tripura kings requested Sultan Barbak Shah to provide manpower for developing the administration of Tripura. As a result, Bengali Hindu bureaucrats, cultivators and artisans began settling in Tripura.[124] Today, the Indian state of Tripura has a Bengali-majority population. Modern Tripura is a gateway for trade and transport links between Bangladesh and Northeast India.[125][126] In Bengali culture, the celebrated singer S. D. Burman was a member of the Tripura royal family.

The flat Bengal Plain, which covers most of Bangladesh and West Bengal, is one of the most fertile areas on Earth, with lush vegetation and farmland dominating its landscape. Bengali villages are buried among groves of mango, jackfruit, betel nut and date palm. Rice, jute, mustard and sugarcane plantations are a common sight. Water bodies and wetlands provide a habitat for many aquatic plants in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta. The northern part of the region features Himalayan foothills (Dooars) with densely wooded Sal and other tropical evergreen trees.[127][128] Above an elevation of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), the forest becomes predominantly subtropical, with a predominance of temperate-forest trees such as oaks, conifers and rhododendrons. Sal woodland is also found across central Bangladesh, particularly in the Bhawal National Park. The Lawachara National Park is a rainforest in northeastern Bangladesh.[129] The Chittagong Hill Tracts in southeastern Bangladesh is noted for its high degree of biodiversity.[130]

The littoral Sundarbans in the southwestern part of Bengal is the largest mangrove forest in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[131] The region has over 89 species of mammals, 628 species of birds and numerous species of fish.[132] For Bangladesh, the water lily, the oriental magpie-robin, the hilsa and mango tree are national symbols. For West Bengal, the white-throated kingfisher, the chatim tree and the night-flowering jasmine are state symbols. The Bengal tiger is the national animal of Bangladesh and India. The fishing cat is the state animal of West Bengal.

Today, the region of Bengal proper is divided between the sovereign state of the People's Republic of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal.[133] The Bengali-speaking Barak Valley forms part of the Indian state of Assam. The Indian state of Tripura has a Bengali-speaking majority and was formerly the princely state of Hill Tipperah. In the Bay of Bengal, St. Martin's Island is governed by Bangladesh; while the Andaman and Nicobar Islands has a plurality of Bengali speakers and is governed by India's federal government as a union territory.

The state of Bangladesh is a parliamentary republic based on the Westminster system, with a written constitution and a President elected by parliament for mostly ceremonial purposes. The government is headed by a Prime Minister, who is appointed by the President from among the popularly elected 300 Members of Parliament in the Jatiyo Sangshad, the national parliament. The Prime Minister is traditionally the leader of the single largest party in the Jatiyo Sangshad. Under the constitution, while recognising Islam as the country's established religion, the constitution grants freedom of religion to non-Muslims.

Between 1975 and 1990, Bangladesh had a presidential system of government. Since the 1990s, it was administered by non-political technocratic caretaker governments on four occasions, the last being under military-backed emergency rule in 2007 and 2008. The Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Jatiya Party (Ershad) are the three largest political parties in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh is a member of the UN, WTO, IMF, the World Bank, ADB, OIC, IDB, SAARC, BIMSTEC and the IMCTC. Bangladesh has achieved significant strides in human development compared to its neighbours.

.jpg/440px-Writer's_Building_(14839639795).jpg)

West Bengal is a constituent state of the Republic of India, with local executives and assemblies- features shared with other states in the Indian federal system. The president of India appoints a governor as the ceremonial representative of the union government. The governor appoints the chief minister on the nomination of the legislative assembly. The chief minister is the traditionally the leader of the party or coalition with most seats in the assembly. President's rule is often imposed in Indian states as a direct intervention of the union government led by the prime minister of India. The Bengali-speaking zone of India carries 48 seats in the lower house of India, Lok Sabha.

Each state has popularly elected members in the Indian lower house of parliament, the Lok Sabha. Each state nominates members to the Indian upper house of parliament, the Rajya Sabha.

The state legislative assemblies also play a key role in electing the ceremonial president of India. The former president of India, Pranab Mukherjee, was a native of West Bengal and a leader of the Indian National Congress. The current leader of opposition of India, Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury is from West Bengal. He has been elected from Baharampur Lok Sabha constituency.

The major political forces in the Bengali-speaking zone of India are the Left Front and the Trinamool Congress, the Indian National Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party. The Bengali-speaking zone of India is considered stronghold for Communism in India. Bengalis are known not to vote on communal lines but in recent years this conception has how changed.[134] The West Bengal based Trinamool Congress is now the third largest party of India in terms of number of MP or MLA after the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Indian National Congress. Earlier the Communist Party of India (Marxist) held this position.

.jpg/440px-Inauguration_of_the_first_edition_of_the_lN-BN_CORPAT_(01).jpg)

India and Bangladesh are the world's first and eighth most populous countries respectively. Bangladesh-India relations began on a high note in 1971 when India played a major role in the liberation of Bangladesh, with the Indian Bengali populace and media providing overwhelming support to the independence movement in the former East Pakistan. The two countries had a twenty five-year friendship treaty between 1972 and 1996. However, differences over river sharing, border security and access to trade have long plagued the relationship. In more recent years, a consensus has evolved in both countries on the importance of developing good relations, as well as a strategic partnership in South Asia and beyond. Commercial, cultural and defence co-operation have expanded since 2010, when Prime Ministers Sheikh Hasina and Manmohan Singh pledged to reinvigorate ties.

The Bangladesh High Commission in New Delhi operates a Deputy High Commission in Kolkata and a consular office in Agartala. India has a High Commission in Dhaka with consulates in Chittagong and Rajshahi. Frequent international air, bus and rail services connect major cities in Bangladesh and Indian Bengal, particularly the three largest cities- Dhaka, Kolkata and Chittagong. Undocumented immigration of Bangladeshi workers is a controversial issue championed by right-wing nationalist parties in India but finds little sympathy in West Bengal.[135] India has since fenced the border which has been criticised by Bangladesh.[136]

.jpg/440px-New_Town_Skyline_captured_from_Bengal_Intelligent_Park,_Saltlake,_Kolkata_(1_of_2_photos).jpg)

The Ganges Delta provided advantages of fertile soil, ample water, and an abundance of fish, wildlife, and fruit.[137] Living standards for Bengal's elite were relatively better than other parts of the Indian subcontinent.[137] Between 400 and 1200, Bengal had a well-developed economy in terms of land ownership, agriculture, livestock, shipping, trade, commerce, taxation, and banking.[138] The apparent vibrancy of the Bengal economy in the beginning of the 15th century is attributed to the end of tribute payments to the Delhi Sultanate, which ceased after the creation of the Bengal Sultanate and stopped the outflow of wealth. Ma Huan's travelogue recorded a booming shipbuilding industry and significant international trade in Bengal.

In 1338, Ibn Battuta noticed that the silver taka was the most popular currency in the region instead of the Islamic dinar.[139] In 1415, members of Admiral Zheng He's entourage also noticed the dominance of the taka. The currency was the most important symbol of sovereignty for the Sultan of Bengal. The Sultanate of Bengal established an estimated 27 mints in provincial capitals across the kingdom.[140][141] These provincial capitals were known as Mint Towns.[142] These Mint Towns formed an integral aspect of governance and administration in Bengal.

The taka continued to be issued in Mughal Bengal, which inherited the sultanate's legacy. As Bengal became more prosperous and integrated into the world economy under Mughal rule, the taka replaced shell currency in rural areas and became the standardised legal tender. It was also used in commerce with the Dutch East India Company, the French East India Company, the Danish East India Company and the British East India Company. Under Mughal rule, Bengal was the centre of the worldwide muslin trade. The muslin trade in Bengal was patronised by the Mughal imperial court. Muslin from Bengal was worn by aristocratic ladies in courts as far away as Europe, Persia and Central Asia. The treasury of the Nawab of Bengal was the biggest source of revenue for the imperial Mughal court in Delhi. Bengal had a large shipbuilding industry. The shipbuilding output of Bengal during the 16th and 17th centuries stood at 223,250 tons annually, which was higher than the volume of shipbuilding in the nineteen colonies of North America between 1769 and 1771.[57]

Historically, Bengal has been the industrial leader of the subcontinent. Mughal Bengal saw the emergence of a proto-industrial economy backed up by textiles and gunpowder. The organised early modern economy flourished till the beginning of British rule in the mid 18th-century, when the region underwent radical and revolutionary changes in government, trade, and regulation. The British displaced the indigenous ruling class and transferred much of the region's wealth back to the colonial metropole in Britain. In the 19th century, the British began investing in railways and limited industrialisation. However, the Bengali economy was dominated by trade in raw materials during much of the colonial period, particularly the jute trade.[143]

The partition of India changed the economic geography of the region. Calcutta in West Bengal inherited a thriving industrial base from the colonial period, particularly in terms of jute processing. East Pakistan soon developed its industrial base, including the world's largest jute mill. In 1972, the newly independent government of Bangladesh nationalised 580 industrial plants. These industries were later privatised in the late 1970s as Bangladesh moved towards a market-oriented economy. Liberal reforms in 1991 paved the way for a major expansion of Bangladesh's private sector industry, including in telecoms, natural gas, textiles, pharmaceuticals, ceramics, steel and shipbuilding. In 2022, Bangladesh was the second largest economy in South Asia after India.[144][145]

The region is one of the largest rice producing areas in the world, with West Bengal being India's largest rice producer and Bangladesh being the world's fourth largest rice producer.[146] Three Bengali economists have been Nobel laureates, including Amartya Sen and Abhijit Banerjee who won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics and Muhammad Yunus who won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Bangladesh and India are the largest trading partners in South Asia, with two-way trade valued at an estimated US$16 billion.[147] Most of this trade relationship is centred on some of the world's busiest land ports on the Bangladesh-India border. The Bangladesh Bhutan India Nepal Initiative seeks to boost trade through a Regional Motor Vehicles Agreement.[148]

The Bengal region is one of the most densely populated areas in the world. With a population of 300 million, Bengalis are the third largest ethnic group in the world after the Han Chinese and Arabs.[a]According to provisional results of 2011 Bangladesh census, the population of Bangladesh was 149,772,364;[149] however, CIA's The World Factbook gives 163,654,860 as its population in a July 2013 estimate. According to the provisional results of the 2011 Indian national census, West Bengal has a population of 91,347,736.[150] "So, the Bengal region, as of 2011[update], has at least 241.1 million people. This figures give a population density of 1003.9/km2; making it among the most densely populated areas in the world.[151][152]

Bengali is the main language spoken in Bengal. Many phonological, lexical, and structural differences from the standard variety occur in peripheral varieties of Bengali across the region. Other regional languages closely related to Bengali include Sylheti, Chittagonian, Chakma, Rangpuri/Rajbangshi, Hajong, Rohingya, and Tangchangya.[153]

English is often used for official work alongside Bangladesh and Indian West Bengal. Other major Indo-Aryan languages such as Hindi, Urdu, Assamese, and Nepali are also familiar to Bengalis in India.[154]

In general, Bengalis are followers of Islam, Hinduism, Christianity and Buddhism with a significant number are Irreligious.

In addition, several minority ethnolinguistic groups are native to the region. These include speakers of other Indo-Aryan languages (e.g., Bishnupriya Manipuri, Oraon Sadri, various Bihari languages), Tibeto-Burman languages (e.g., A'Tong, Chak, Koch, Garo, Megam, Meitei (officially called "Manipuri"), Mizo, Mru, Pangkhua, Rakhine/Marma, Kok Borok, Riang, Tippera, Usoi, various Chin languages), Austroasiatic languages (e.g., Khasi, Koda, Mundari, Pnar, Santali, War), and Dravidian languages (e.g., Kurukh, Sauria Paharia).[153]

Life expectancy is around 72.49 years for Bangladesh[158] and 70.2 for West Bengal.[159][160] In terms of literacy, West Bengal leads with 77% literacy rate,[151] in Bangladesh the rate is approximately 72.9%.[161][b] The level of poverty in West Bengal is at 19.98%, while in Bangladesh it stands at 12.9%[162][163][164]

West Bengal has one of the lowest total fertility rates in India. West Bengal's TFR of 1.6 roughly equals that of Canada.[165]

The Bengali language developed between the 7th and 10th centuries from Apabhraṃśa and Magadhi Prakrit.[166] It is written using the indigenous Bengali alphabet, a descendant of the ancient Brahmi script. Bengali is the 5th most spoken language in the world. It is an eastern Indo-Aryan language and one of the easternmost branches of the Indo-European language family. It is part of the Bengali-Assamese languages. Bengali has greatly influenced other languages in the region, including Odia, Assamese, Chakma, Nepali and Rohingya. It is the sole state language of Bangladesh and the second most spoken language in India.[167] It is also the seventh most spoken language by total number of speakers in the world.

Bengali binds together a culturally diverse region and is an important contributor to regional identity. The 1952 Bengali Language Movement in East Pakistan is commemorated by UNESCO as International Mother Language Day, as part of global efforts to preserve linguistic identity.

In both Bangladesh and West Bengal, currency is commonly denominated as taka. The Bangladesh taka is an official standard bearer of this tradition, while the Indian rupee is also written as taka in Bengali script on all of its banknotes. The history of the taka dates back centuries. Bengal was home one of the world's earliest coin currencies in the first millennium BCE. Under the Delhi Sultanate, the taka was introduced by Muhammad bin Tughluq in 1329. Bengal became the stronghold of the taka. The silver currency was the most important symbol of sovereignty of the Sultanate of Bengal. It was traded on the Silk Road and replicated in Nepal and China's Tibetan protectorate. The Pakistani rupee was scripted in Bengali as taka on its banknotes until Bangladesh's creation in 1971.

Bengali literature has a rich heritage. It has a history stretching back to the 3rd century BCE, when the main language was Sanskrit written in the brahmi script. The Bengali language and script evolved c. 1000 CE from Magadhi Prakrit. Bengal has a long tradition in folk literature, evidenced by the Chôrjapôdô, Mangalkavya, Shreekrishna Kirtana, Maimansingha Gitika or Thakurmar Jhuli. Bengali literature in the medieval age was often either religious (e.g. Chandidas), or adaptations from other languages (e.g. Alaol). During the Bengal Renaissance of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Bengali literature was modernised through the works of authors such as Michael Madhusudan Dutta, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Rabindranath Tagore, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Satyendranath Dutta, Begum Rokeya and Jibanananda Das. In the 20th century, prominent modern Bengali writers included Syed Mujtaba Ali, Jasimuddin, Manik Bandopadhyay, Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, Buddhadeb Bose, Sunil Gangopadhyay and Humayun Ahmed.

Prominent contemporary Bengali writers in English include Amitav Ghosh, Tahmima Anam, Jhumpa Lahiri and Zia Haider Rahman among others.

The Bangamata is a female personification of Bengal which was created during the Bengali Renaissance and later adopted by the Bengali nationalists.[168] Hindu nationalists adopted a modified Bharat Mata as a national personification of India.[169] The Mother Bengal represents not only biological motherness but its attributed characteristics as well – protection, never ending love, consolation, care, the beginning and the end of life. In Amar Sonar Bangla, the national anthem of Bangladesh, Rabindranath Tagore has used the word "Maa" (Mother) numerous times to refer to the motherland i.e. Bengal.

The Pala-Sena School of Art developed in Bengal between the 8th and 12th centuries and is considered a high point of classical Asian art.[170][171] It included sculptures and paintings.[172]

Islamic Bengal was noted for its production of the finest cotton fabrics and saris, notably the Jamdani, which received warrants from the Mughal court.[173] The Bengal School of painting flourished in Kolkata and Shantiniketan in the British Raj during the early 20th century. Its practitioners were among the harbingers of modern painting in India.[174] Zainul Abedin was the pioneer of modern Bangladeshi art. The country has a thriving and internationally acclaimed contemporary art scene.[175]

Classical Bengali architecture features terracotta buildings. Ancient Bengali kingdoms laid the foundations of the region's architectural heritage through the construction of monasteries and temples (for example, the Somapura Mahavihara). During the sultanate period, a distinct and glorious Islamic style of architecture developed the region.[176] Most Islamic buildings were small and highly artistic terracotta mosques with multiple domes and no minarets. Bengal was also home to the largest mosque in South Asia at Adina. Bengali vernacular architecture is credited for inspiring the popularity of the bungalow.[177]

The Bengal region also has a rich heritage of Indo-Saracenic architecture, including numerous zamindar palaces and mansions. The most prominent example of this style is the Victoria Memorial, Kolkata.

In the 1950s, Muzharul Islam pioneered the modernist terracotta style of architecture in South Asia. This was followed by the design of the Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban by the renowned American architect Louis Kahn in the 1960s, which was based on the aesthetic heritage of Bengali architecture and geography.[178][179]

The Gupta dynasty, which is believed to have originated in North Bengal, pioneered the invention of chess, the concept of zero, the theory of Earth orbiting the Sun, the study of solar and lunar eclipses and the flourishing of Sanskrit literature and drama.[30][180]<

The educational reforms during the British Raj gave birth to many distinguished scientists in Bengal. Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose pioneered the investigation of radio and microwave optics, made very significant contributions to plant science, and laid the foundations of experimental science in the Indian subcontinent.[181] IEEE named him one of the fathers of radio science.[182] He was the first person from the Indian subcontinent to receive a US patent, in 1904. In 1924–25, while researching at the University of Dhaka, Satyendra Nath Bose well known for his works in quantum mechanics, provided the foundation for Bose–Einstein statistics and the theory of the Bose–Einstein condensate.[183][184][185] Meghnad Saha was the first scientist to relate a star's spectrum to its temperature, developing thermal ionization equations (notably the Saha ionization equation) that have been foundational in the fields of astrophysics and astrochemistry.[186] Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri was a physicist, known for his research in general relativity and cosmology. His most significant contribution is the eponymous Raychaudhuri equation, which demonstrates that singularities arise inevitably in general relativity and is a key ingredient in the proofs of the Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems.[187]

In the United States, the Bangladeshi-American engineer Fazlur Rahman Khan emerged as the "father of tubular designs" in skyscraper construction. Ashoke Sen is an Indian theoretical physicist whose main area of work is string theory. He was among the first recipients of the Fundamental Physics Prize "for opening the path to the realisation that all string theories are different limits of the same underlying theory".[188]

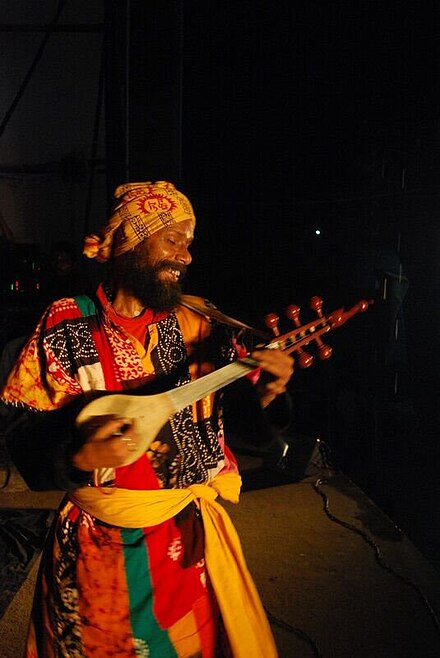

The Baul tradition is a unique heritage of Bengali folk music.[189] The 19th century mystic poet Lalon Shah is the most celebrated practitioner of the tradition.[190] Other folk music forms include Gombhira, Bhatiali and Bhawaiya. Hason Raja is a renowned folk poet of the Sylhet region. Folk music in Bengal is often accompanied by the ektara, a one-stringed instrument. Other instruments include the dotara, dhol, flute, and tabla. The region also has a rich heritage in North Indian classical music.

Bengali cuisine is the only traditionally developed multi-course tradition from the Indian subcontinent. Rice and fish are traditional favourite foods, leading to a saying that "fish and rice make a Bengali".[191] Bengal's vast repertoire of fish-based dishes includes Hilsa preparations, a favourite among Bengalis. Bengalis make distinctive sweetmeats from milk products, including Rôshogolla, Chômchôm, and several kinds of Pithe. The old city of Dhaka is noted for its distinct Indo-Islamic cuisine, including biryani, bakarkhani and kebab dishes.

There are 150 types of Bengali country boats plying the 700 rivers of the Bengal delta, the vast floodplain and many oxbow lakes. They vary in design and size. The boats include the dinghy and sampan among others. Country boats are a central element of Bengali culture and have inspired generations of artists and poets, including the ivory artisans of the Mughal era. The country has a long shipbuilding tradition, dating back many centuries. Wooden boats are made of timber such as Jarul (dipterocarpus turbinatus), sal (shorea robusta), sundari (heritiera fomes), and Burma teak (tectons grandis). Medieval Bengal was shipbuilding hub for the Mughal and Ottoman navies.[192][193] The British Royal Navy later utilised Bengali shipyards in the 19th century, including for the Battle of Trafalgar.

Bengali women commonly wear the shaŗi , often distinctly designed according to local cultural customs. In urban areas, many women and men wear Western-style attire. Among men, European dressing has greater acceptance. Men also wear traditional costumes such as the panjabi[194] with dhoti or pyjama, often on religious occasions. The lungi, a kind of long skirt, is widely worn by Bangladeshi men.[citation needed]

.jpg/440px-Mongol_Shobhajatra,_Pohela_Boishakh_(18).jpg)

For Bengali Muslims, the major religious festivals are Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha, Mawlid, Muharram, and Shab-e-Barat. For Bengali Hindus, the major religious festivals include Durga Puja, Kali Puja, Janmashtami and Rath Yatra. In honour of Bengali Buddhists and Bengali Christians, both Buddha's Birthday and Christmas are public holidays in the region. The Bengali New Year is the main secular festival of Bengali culture celebrated by people regardless of religious and social backgrounds. The biggest congregation in Bengal is the Bishwa ijtema, which is also the world's second largest Islamic congregation. Other Bengali festivals include the first day of spring and the Nabanna harvest festival in autumn.

Bangladesh has a diverse, outspoken and privately owned press, with the largest circulated Bengali language newspapers in the world. English-language titles are popular in the urban readership.[195] West Bengal had 559 published newspapers in 2005,[196] of which 430 were in Bengali.[196] Bengali cinema is divided between the media hubs of Dhaka and Kolkata.

Cricket and football are popular sports in the Bengal region. Local games include sports such as Kho Kho and Kabaddi, the latter being the national sport of Bangladesh. An Indo-Bangladesh Bengali Games has been organised among the athletes of the Bengali speaking areas of the two countries.[197]

Also, we have the reference to 'Vangalam' in an inscription in the Vrihadeshwara temple at Tanjore in south India as one among the countries overrun by the Cholas. This is perhaps the earliest reference to Bengal as such.

In C1020 ... launched Rajendra's great northern escapade ... peoples he defeated have been tentatively identified ... 'Vangala-desa where the rain water never stopped' sounds like a fair description of Bengal in the monsoon.

By the time Muhammad Bakhtiyar conquered northwestern Bengal in 1204

[Husayn Shah pushed] its western frontier past Bihar up to Saran in Jaunpur ... when Sultan Husayn Shah Sharqi of Jaunpur fled to Bengal after being defeated in battle by Sultan Sikandar Lodhi of Delhi, the latter attacked Bengal in pursuit of the Jaunpur ruler. Unable to make any gains, Sikandar Lodhi returned home after concluding a peace treaty with the Bengal sultan.

The 1769-1770 famine in Bengal followed two years of erratic rainfall worsened by a smallpox epidemic.

Malaria was endemic in rural areas during the 19th century, particularly in western Bengal. This was ... The famine of 1769–70 resulted in about ten million deaths, while 50 million died of malaria, plague and famine between 1895 and 19206.

in Samatata (South-east Bengal) where the Buddhist Khadaga dynasty ruled throughout the fifth, sixth and seventh centuries AD.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)Population By Religion (%) Muslim 90.39 Hindu 8.54 Buddhist 0.60 Christian 0.37 Others 0.14