Лошадь ( Equus ferus caballus ) [2] [3] — одомашненное однопалое копытное млекопитающее. Оно принадлежит к таксономическому семейству Equidae и является одним из двух сохранившихся подвидов Equus ferus . За последние 45–55 миллионов лет лошадь превратилась из небольшого многопалого существа, близкого к Eohippus , в крупное однопалое животное наших дней. Люди начали одомашнивать лошадей около 4000 г. до н. э. , и считается, что их одомашнивание было широко распространено к 3000 г. до н. э. Лошади подвида caballus одомашнены, хотя некоторые одомашненные популяции живут в дикой природе как одичавшие лошади . Эти одичавшие популяции не являются настоящими дикими лошадьми , которые представляют собой лошадей, которые никогда не были одомашнены и исторически связаны с категорией видов мегафауны. Для описания понятий, связанных с лошадьми, используется обширный специализированный словарь, охватывающий все: от анатомии до стадий жизни, размера, окраса , отметин , пород , передвижения и поведения.

Лошади приспособлены к бегу , что позволяет им быстро убегать от хищников, и обладают хорошим чувством равновесия и сильной реакцией «бей или беги» . С этой потребностью убегать от хищников в дикой природе связана необычная черта: лошади способны спать как стоя, так и лежа, причем молодые лошади, как правило, спят значительно больше взрослых. [4] Самки лошадей, называемые кобылами , вынашивают своих детенышей примерно 11 месяцев, а молодая лошадь, называемая жеребенком , может стоять и бегать вскоре после рождения. Большинство одомашненных лошадей начинают тренироваться под седлом или в упряжи в возрасте от двух до четырех лет. Они достигают полного развития взрослой особи к пяти годам и имеют среднюю продолжительность жизни от 25 до 30 лет.

Породы лошадей можно условно разделить на три категории в зависимости от общего темперамента: резвые «горячие крови» с быстротой и выносливостью; «холодные крови», такие как упряжные лошади и некоторые пони , подходящие для медленной, тяжелой работы; и « теплокровные », выведенные путем скрещивания горячих и холоднокровных лошадей, часто с упором на создание пород для определенных целей верховой езды, особенно в Европе. Сегодня в мире существует более 300 пород лошадей, выведенных для самых разных целей.

Лошади и люди взаимодействуют в самых разных спортивных соревнованиях и неконкурентных рекреационных занятиях, а также в рабочих видах деятельности, таких как работа в полиции , сельское хозяйство , развлечения и терапия . Лошади исторически использовались в военных действиях, из которых развилось множество методов верховой езды и вождения , использующих множество различных стилей снаряжения и методов контроля. Многие продукты получены от лошадей, включая мясо , молоко , шкуру , шерсть , кости и фармацевтические препараты, извлеченные из мочи беременных кобыл . Люди обеспечивают одомашненных лошадей едой, водой и кровом, а также вниманием со стороны таких специалистов, как ветеринары и кузнецы .

В зависимости от породы, содержания и окружающей среды, продолжительность жизни современной домашней лошади составляет от 25 до 30 лет. [7] Редко встречаются животные, доживающие до 40 лет, а иногда и дольше. [8] Самым старым подтвержденным рекордом был « Старый Билли », лошадь 19 века, прожившая до 62 лет . [7] В наше время Шугар Пафф, занесенный в Книгу рекордов Гиннесса как старейший в мире живущий пони, умер в 2007 году в возрасте 56 лет . [9]

Независимо от фактической даты рождения лошади или пони, для большинства целей соревнований к ее возрасту прибавляется год 1 января каждого года в Северном полушарии [7] [10] и 1 августа каждого года в Южном полушарии. [11] Исключением является конный спорт на выносливость , где минимальный возраст для участия в соревнованиях основан на фактическом календарном возрасте животного. [12]

Для описания лошадей разного возраста используется следующая терминология:

В скачках эти определения могут различаться: например, на Британских островах в скачках чистокровных лошадей жеребята и кобылы определяются как лошади моложе пяти лет. [21] Однако в австралийских скачках чистокровных лошадей жеребята и кобылы определяются как лошади моложе четырех лет. [22]

Высота лошадей измеряется в самой высокой точке холки , где шея соединяется со спиной . [23] Эта точка используется, потому что она является стабильной точкой анатомии, в отличие от головы или шеи, которые движутся вверх и вниз по отношению к телу лошади.

В англоязычных странах высота лошадей часто указывается в единицах измерения ладоней и дюймов: одна ладонь равна 4 дюймам (101,6 мм). Высота выражается как количество полных ладоней, за которыми следует точка , затем количество дополнительных дюймов и заканчивается сокращением «h» или «hh» (для «hands high»). Таким образом, лошадь, описанная как «15,2 h», имеет высоту 15 ладоней плюс 2 дюйма, что в сумме составляет 62 дюйма (157,5 см). [24]

Размер лошадей варьируется в зависимости от породы, но также зависит от питания . Лошади легкой верховой езды обычно имеют рост от 14 до 16 ладоней (от 56 до 64 дюймов, от 142 до 163 см) и могут весить от 380 до 550 килограммов (от 840 до 1210 фунтов). [25] Лошади более крупной верховой езды обычно начинаются с роста около 15,2 ладоней (62 дюйма, 157 см) и часто достигают высоты 17 ладоней (68 дюймов, 173 см) и веса от 500 до 600 килограммов (от 1100 до 1320 фунтов). [26] Лошади тяжелой или упряжной породы обычно имеют рост не менее 16 ладоней (64 дюйма, 163 см) и могут достигать высоты 18 ладоней (72 дюйма, 183 см). Они могут весить от 700 до 1000 килограммов (от 1540 до 2200 фунтов). [27]

Самой большой лошадью в истории, вероятно, была лошадь породы шайр по кличке Мамонт , родившаяся в 1848 году. Ее рост составлял 21,2 м. 1 ⁄ 4 ладони (86,25 дюйма, 219 см) в высоту, а его максимальный вес оценивался в 1524 килограмма (3360 фунтов). [28] Рекордсменкой среди самых маленьких лошадей является Дюймовочка , полностью взрослая миниатюрная лошадь, страдающая карликовостью . Она была ростом 43 сантиметра; 4,1 ладони (17 дюймов) в высоту и весила 26 кг (57 фунтов). [29] [30]

Пони таксономически являются теми же животными, что и лошади. Различие между лошадью и пони обычно проводится на основе высоты, особенно в целях соревнований. Однако высота сама по себе не является решающей; разница между лошадьми и пони может также включать аспекты фенотипа , включая экстерьер и темперамент.

Традиционный стандарт высоты лошади или пони в зрелом возрасте составляет 14,2 ладони (58 дюймов, 147 см). Животное ростом 14,2 ладони (58 дюймов, 147 см) или выше обычно считается лошадью, а животное ростом менее 14,2 ладони (58 дюймов, 147 см) — пони, [31] : 12, но есть много исключений из традиционного стандарта. В Австралии пони считаются те, кто ниже 14 ладоней (56 дюймов, 142 см). [32] Для соревнований в Западном дивизионе Федерации конного спорта США порог составляет 14,1 ладони (57 дюймов, 145 см). [33] Международная федерация конного спорта , всемирный руководящий орган по конному спорту, использует метрическую систему измерений и определяет пони как любую лошадь ростом менее 148 сантиметров (58,27 дюйма) в холке без подков, что составляет чуть более 14,2 ладоней (58 дюймов, 147 см) и 149 сантиметров (58,66 дюйма; 14,2 дюйма)+1 ⁄ 2 руки), с обувью. [34]

Рост — не единственный критерий для различения лошадей и пони. Реестры пород лошадей, которые обычно производят особей ростом как ниже, так и выше 14,2 ладоней (58 дюймов, 147 см), считают всех животных этой породы лошадьми независимо от их роста. [35] И наоборот, некоторые породы пони могут иметь общие черты с лошадьми, и отдельные животные могут иногда достигать зрелости при росте выше 14,2 ладоней (58 дюймов, 147 см), но все равно считаться пони. [36]

Пони часто демонстрируют более густые гривы, хвосты и общую шерсть. У них также пропорционально более короткие ноги, более широкие бочка, более тяжелый костяк, более короткие и толстые шеи и короткие головы с широкими лбами. У них может быть более спокойный темперамент, чем у лошадей, а также высокий уровень интеллекта, который может или не может использоваться для сотрудничества с людьми-дрессировщиками. [31] : 11–12 [ неудачная проверка ] Маленький размер сам по себе не является исключительным определяющим фактором. Например, шетландский пони , который в среднем составляет 10 ладоней (40 дюймов, 102 см), считается пони. [31] : 12 И наоборот, такие породы, как фалабелла и другие миниатюрные лошади , которые не могут быть выше 76 сантиметров; 7,2 ладоней (30 дюймов), классифицируются их регистрами как очень маленькие лошади, а не пони. [37]

У лошадей 64 хромосомы . [38] Геном лошади был секвенирован в 2007 году. Он содержит 2,7 миллиарда пар оснований ДНК , [39] что больше, чем геном собаки , но меньше, чем геном человека или геном коровы . [40] Карта доступна исследователям. [41]

Лошади демонстрируют разнообразный спектр окрасов шерсти и отличительных отметин , которые описываются специализированным словарем. Часто лошадь классифицируется сначала по окрасу шерсти, а затем по породе или полу. [42] Лошади одного цвета могут отличаться друг от друга белыми отметинами , [43] которые, наряду с различными узорами пятен, наследуются отдельно от окраса шерсти. [44]

Было идентифицировано множество генов , которые создают окрас и узоры шерсти лошадей. Текущие генетические тесты могут идентифицировать по крайней мере 13 различных аллелей, влияющих на окрас шерсти, [45] и исследования продолжают открывать новые гены, связанные с определенными признаками. Основные окрасы шерсти каштановый и черный определяются геном, контролируемым рецептором меланокортина 1 , [46] также известным как «ген расширения» или «фактор красного». [45] Его рецессивная форма — «красный» (каштановый), а его доминантная форма — черный. [47] Дополнительные гены контролируют подавление черного цвета до пойнтовой окраски , что приводит к гнедой , пятнистым рисункам, таким как пегий или леопард , генам разбавления, таким как паломино или буланый , а также поседению и всем другим факторам, которые создают множество возможных окрасов шерсти, встречающихся у лошадей. [45]

Лошади с белой мастью часто неправильно маркируются; лошадь, которая выглядит «белой», обычно является серой среднего или старшего возраста . Серые рождаются более темного оттенка, становятся светлее с возрастом, но обычно сохраняют черную кожу под своей белой шерстью (за исключением розовой кожи под белыми отметинами ). Единственные лошади, которых правильно называют белыми, рождаются с преимущественно белой шерстью и розовой кожей, что встречается довольно редко. [47] Различные и не связанные между собой генетические факторы могут вызывать белый окрас у лошадей, включая несколько различных аллелей доминирующего белого и гена sabino-1 . [48] Однако не существует лошадей « альбиносов », определяемых как имеющие как розовую кожу, так и красные глаза. [49]

Беременность длится приблизительно 340 дней, со средним диапазоном 320–370 дней, [50] [51] и обычно заканчивается рождением одного жеребенка ; близнецы редки. [52] Лошади являются выводковым видом, и жеребята способны стоять и бегать в течение короткого времени после рождения. [53] Жеребята обычно рождаются весной. Эстральный цикл кобылы происходит примерно каждые 19–22 дня и длится с ранней весны до осени. Большинство кобыл вступают в период анэструса зимой и, таким образом, не циклируются в этот период. [54] Жеребят, как правило, отнимают от своих матерей в возрасте от четырех до шести месяцев. [55]

Лошади, особенно жеребята, иногда физически способны к размножению примерно в 18 месяцев, но одомашненным лошадям редко позволяют размножаться до трехлетнего возраста, особенно самкам. [31] : 129 Лошади четырех лет считаются зрелыми, хотя скелет обычно продолжает развиваться до шестилетнего возраста; созревание также зависит от размера лошади, породы, пола и качества ухода. У более крупных лошадей кости крупнее; поэтому не только костям требуется больше времени для формирования костной ткани , но и эпифизарные пластины крупнее и требуют больше времени для преобразования из хряща в кость. Эти пластины преобразуются после других частей костей и имеют решающее значение для развития. [56]

В зависимости от зрелости, породы и ожидаемой работы, лошадей обычно седлают и тренируют для верховой езды в возрасте от двух до четырех лет. [57] Хотя в некоторых странах чистокровных скаковых лошадей выпускают на трассу в возрасте двух лет, [58] лошадей, специально выведенных для таких видов спорта, как выездка, обычно не седлают, пока им не исполнится три или четыре года, потому что их кости и мышцы еще не достаточно развиты. [59] Для соревнований по выносливости лошади не считаются достаточно зрелыми для участия, пока им не исполнится полных 60 календарных месяцев (пять лет). [12]

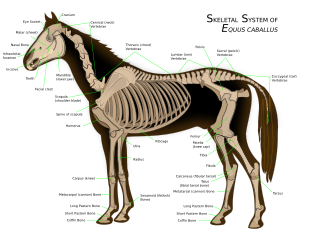

Скелет лошади в среднем состоит из 205 костей. [60] Существенным отличием между скелетом лошади и скелетом человека является отсутствие ключицы — передние конечности лошади прикреплены к позвоночнику мощным набором мышц, сухожилий и связок, которые прикрепляют лопатку к туловищу. Четыре ноги и копыта лошади также являются уникальными структурами. Кости их ног пропорциональны иным, чем у человека. Например, часть тела, которая называется «коленом» лошади, на самом деле состоит из костей запястья , которые соответствуют человеческому запястью . Аналогично, скакательный сустав содержит кости, эквивалентные костям в человеческой лодыжке и пятке . Кости голени лошади соответствуют костям человеческой руки или ноги, а путовый сустав (неправильно называемый «лодыжкой») на самом деле является проксимальной сесамовидной костью между пястными костями (единый эквивалент человеческой пястной или плюсневой кости ) и проксимальными фалангами , расположенными там, где находятся «костяшки» человека. У лошади также нет мышц в ногах ниже колен и скакательных суставов, только кожа, волосы, кости, сухожилия , связки , хрящи и различные специализированные ткани, которые составляют копыто . [61]

Критическая важность стоп и ног суммируется традиционной поговоркой: «нет стопы, нет лошади». [62] Лошадиное копыто начинается с дистальных фаланг , эквивалента кончика пальца руки или ноги человека, окруженных хрящом и другими специализированными, богатыми кровью мягкими тканями, такими как пластинки . Внешняя стенка копыта и рог подошвы состоят из кератина , того же материала, что и человеческий ноготь . [63] В результате лошадь, весящая в среднем 500 килограммов (1100 фунтов), [64] передвигается на тех же костях, что и человек на цыпочках. [65] Для защиты копыта в определенных условиях некоторым лошадям профессиональный кузнец надевает на ноги подковы . Копыто постоянно растет, и у большинства домашних лошадей его необходимо подрезать (и переподковывать , если они используются) каждые пять-восемь недель [66] , хотя копыта лошадей в дикой природе изнашиваются и отрастают со скоростью, подходящей для их местности.

Лошади приспособлены к выпасу . У взрослой лошади в передней части рта есть 12 резцов , приспособленных для откусывания травы или другой растительности. В задней части рта есть 24 зуба, приспособленных для жевания, премоляры и моляры . У жеребцов и меринов есть четыре дополнительных зуба сразу за резцами, тип клыков, называемых «клювами». У некоторых лошадей, как самцов, так и самок, также развивается от одного до четырех очень маленьких рудиментарных зубов перед молярами, известных как «волчьи» зубы, которые обычно удаляются, потому что они могут мешать удилам . Между резцами и молярами есть пустое межзубное пространство, где удила опираются непосредственно на десны, или «перекладины» рта лошади, когда лошадь взнуздана . [ 67]

Оценить возраст лошади можно, посмотрев на ее зубы. Зубы продолжают прорезываться в течение всей жизни и изнашиваются под воздействием выпаса. Поэтому резцы изменяются по мере старения лошади; они приобретают отчетливый рисунок износа, меняют форму зубов и угол, под которым встречаются жевательные поверхности. Это позволяет очень грубо оценить возраст лошади, хотя диета и ветеринарный уход также могут влиять на скорость износа зубов. [7]

Лошади — травоядные животные с пищеварительной системой, адаптированной к кормовому рациону из трав и других растительных материалов, потребляемых постоянно в течение дня. Поэтому, по сравнению с людьми, у них относительно небольшой желудок, но очень длинный кишечник, что обеспечивает постоянный поток питательных веществ. Лошадь весом 450 кг (990 фунтов) съедает от 7 до 11 килограммов (от 15 до 24 фунтов) пищи в день и при нормальном использовании выпивает от 38 до 45 литров (от 8,4 до 9,9 имп галлонов; от 10 до 12 галлонов США) воды . Лошади не являются жвачными животными , у них только один желудок, как у людей. Но в отличие от людей, они могут переваривать целлюлозу , основной компонент травы, посредством процесса ферментации в задней кишке . Ферментация целлюлозы симбиотическими бактериями и другими микробами происходит в слепой кишке и толстом кишечнике . Лошади не могут рвать , поэтому проблемы с пищеварением могут быстро вызвать колики , одну из основных причин смерти. [68] Хотя у лошадей нет желчного пузыря , они переносят большое количество жира в своем рационе. [69] [70]

Чувства лошадей основаны на их статусе добычи , где они должны постоянно осознавать свое окружение. [71] Они имеют боковые глаза, что означает, что их глаза расположены по бокам головы. [72] Это означает, что у лошадей диапазон зрения более 350°, из которых примерно 65° — это бинокулярное зрение , а оставшиеся 285° — монокулярное зрение . [73] У лошадей отличное дневное и ночное зрение , но у них двухцветное или дихроматическое зрение ; их цветовое зрение чем-то похоже на красно-зеленую цветовую слепоту у людей, когда определенные цвета, особенно красный и родственные цвета, кажутся оттенками зеленого. [74]

Их обоняние , хотя и намного лучше, чем у людей, не такое хорошее, как у собак. Считается, что оно играет ключевую роль в социальных взаимодействиях лошадей, а также в обнаружении других ключевых запахов в окружающей среде. У лошадей есть два обонятельных центра. Первая система находится в ноздрях и носовой полости, которые анализируют широкий спектр запахов. Вторая, расположенная под носовой полостью, — это вомероназальные органы , также называемые органами Якобсона. Они имеют отдельный нервный путь к мозгу и, по-видимому, в первую очередь анализируют феромоны . [75]

У лошадей хороший слух, [71] а ушная раковина каждого уха может вращаться до 180°, что дает возможность слышать на 360° без необходимости поворачивать голову. [76] Шум влияет на поведение лошадей, а некоторые виды шума могут способствовать стрессу — исследование, проведенное в Великобритании в 2013 году, показало, что лошади в конюшнях были спокойнее в тихой обстановке или при прослушивании кантри или классической музыки, но проявляли признаки нервозности при прослушивании джаза или рок-музыки. В этом исследовании также рекомендовалось поддерживать громкость музыки ниже 21 децибела . [ 77] Австралийское исследование показало, что у скаковых лошадей в конюшнях, слушающих разговорное радио, был более высокий уровень язв желудка, чем у лошадей, слушающих музыку, а у скаковых лошадей, содержащихся в конюшнях, где играло радио, был более высокий общий уровень язв, чем у лошадей, содержащихся в конюшнях, где не играло радио. [78]

Лошади обладают прекрасным чувством равновесия, отчасти благодаря их способности чувствовать свою опору, а отчасти благодаря высокоразвитой проприорецепции — бессознательному чувству того, где в любой момент времени находятся тело и конечности. [79] У лошадей хорошо развито осязание . Наиболее чувствительные области находятся вокруг глаз, ушей и носа. [80] Лошади способны ощущать такой тонкий контакт, как приземление насекомого в любой точке тела. [81]

Лошади обладают развитым чувством вкуса, что позволяет им сортировать корм и выбирать то, что им больше всего нравится есть, [82] а их цепкие губы могут легко сортировать даже мелкие зерна. Лошади, как правило, не едят ядовитые растения, однако есть исключения; лошади иногда едят ядовитые растения в токсичных количествах, даже когда есть достаточно здоровой пищи. [83]

Все лошади двигаются естественным образом четырьмя основными аллюрами : [84]

Помимо этих основных аллюров, некоторые лошади выполняют двухтактный шаг вместо рыси. [87] Существует также несколько четырехтактных « иноходных » аллюров, которые приблизительно соответствуют скорости рыси или шага, хотя и более плавные для езды. К ним относятся боковая стойка , бегущий шаг и тёльт , а также диагональный фокстрот . [88] Иноходные аллюры часто являются генетическими у некоторых пород, известных под общим названием иноходные лошади . [89] Эти лошади заменяют рысь одним из иноходных аллюров. [90]

Лошади — это животные-жертвы с сильной реакцией «бей или беги» . Их первая реакция на угрозу — испугаться и обычно убежать, хотя они будут стоять на своем и защищаться, когда бегство невозможно или если их детенышам угрожает опасность. [91] Они также склонны к любопытству; будучи напуганы, они часто на мгновение колеблются, чтобы выяснить причину своего испуга, и не всегда могут убежать от чего-то, что они считают не угрожающим. Большинство пород легких верховых лошадей были выведены для скорости, ловкости, бдительности и выносливости; природные качества, которые унаследованы от их диких предков. Однако благодаря селективному разведению некоторые породы лошадей довольно послушны, особенно некоторые тяжеловозные лошади. [92]

Лошади — стадные животные с четкой иерархией рангов, во главе с доминирующей особью, обычно кобылой. Они также являются социальными существами, которые способны формировать товарищеские привязанности к своему виду и к другим животным, включая людей. Они общаются различными способами, включая вокализации, такие как ржание или ржание, взаимный уход и язык тела . Многих лошадей будет трудно контролировать, если они изолированы, но с обучением лошади могут научиться принимать человека в качестве компаньона и, таким образом, чувствовать себя комфортно вдали от других лошадей. [93] Однако, когда они ограничены недостаточным общением, упражнениями или стимуляцией, у особей могут развиться устойчивые пороки , набор плохих привычек, в основном стереотипии психологического происхождения, которые включают жевание древесины, пинание стен, «плетение» (раскачивание вперед и назад) и другие проблемы. [94]

Исследования показали, что лошади ежедневно выполняют ряд когнитивных задач, решая умственные задачи, включающие добычу пищи и идентификацию людей в социальной системе . Они также обладают хорошими способностями к пространственному различению . [95] Они от природы любопытны и склонны исследовать вещи, которые они раньше не видели. [96] Исследования оценивали интеллект лошадей в таких областях, как решение проблем , скорость обучения и память . Лошади преуспевают в простом обучении, но также способны использовать более продвинутые когнитивные способности, которые включают категоризацию и обучение концепциям . Они могут учиться, используя привыкание , десенсибилизацию , классическое обусловливание и оперантное обусловливание , а также положительное и отрицательное подкрепление . [95] Одно исследование показало, что лошади могут различать «больше» и «меньше», если вовлеченное количество меньше четырех. [97]

Домашние лошади могут сталкиваться с большими умственными проблемами, чем дикие лошади, потому что они живут в искусственной среде, которая препятствует инстинктивному поведению, а также обучаются задачам, которые не являются естественными. [95] Лошади — это животные привычки , которые хорошо реагируют на регламентацию и лучше всего реагируют, когда одни и те же процедуры и методы используются последовательно. Один тренер считает, что «умные» лошади являются отражением умных тренеров, которые эффективно используют методы обусловливания реакции и положительное подкрепление для обучения в стиле, который лучше всего соответствует естественным наклонностям отдельного животного. [98]

Лошади — млекопитающие . Как таковые, они являются теплокровными , или эндотермическими, существами, в отличие от холоднокровных, или пойкилотермных животных. Однако эти слова приобрели отдельное значение в контексте терминологии лошадей, используемой для описания темперамента, а не температуры тела . Например, « горячекровые », такие как многие скаковые лошади , проявляют большую чувствительность и энергию, [99] в то время как «холоднокровные», такие как большинство тяжеловозных пород , более тихие и спокойные. [100] Иногда «горячекровых» классифицируют как «легких лошадей» или «верховых лошадей», [101] а «холоднокровных» классифицируют как «тяжеловозов» или «рабочих лошадей». [102]

«Горячие» породы включают « восточных лошадей », таких как ахалтекинская , арабская , берберийская и ныне вымершая туркменская , а также чистокровная верховая , порода, выведенная в Англии из более старых восточных пород. [99] Горячие лошади, как правило, энергичны, смелы и быстро обучаются. Их разводят для ловкости и скорости. [103] Они, как правило, физически утонченны — тонкокожие, стройные и длинноногие. [104] Первоначальные восточные породы были завезены в Европу с Ближнего Востока и Северной Африки, когда европейские селекционеры хотели привить эти черты скаковым и легким кавалерийским лошадям. [105] [106]

Мускулистые, тяжеловозные лошади известны как «холоднокровные». Их разводят не только ради силы, но и для того, чтобы они обладали спокойным, терпеливым темпераментом, необходимым для того, чтобы тянуть плуг или тяжелую повозку, полную людей. [100] Иногда их называют «нежными великанами». [107] Известные тяжеловозные породы включают бельгийскую и клейдесдальскую . [107] Некоторые, такие как першерон , легче и живее, выведены для того, чтобы тянуть повозки или пахать большие поля в более сухом климате. [108] Другие, такие как шайр , медленнее и мощнее, выведены для пахоты полей с тяжелыми почвами на основе глины. [109] В группу холоднокровных также входят некоторые породы пони. [110]

« Теплокровные » породы, такие как тракененская или ганноверская , появились, когда европейские упряжные и боевые лошади были скрещены с арабскими или чистокровными, в результате чего получилась верховая лошадь с большей утонченностью, чем упряжная лошадь, но большего размера и более мягким темпераментом, чем более легкая порода. [111] Некоторые породы пони с характеристиками теплокровных были выведены для более мелких всадников. [112] Теплокровные лошади считаются «легкими лошадьми» или «верховыми лошадьми». [101]

Сегодня термин «теплокровные» относится к определенному подвиду спортивных пород лошадей, которые используются для соревнований по выездке и конкуру . [113] Строго говоря, термин « теплокровные » относится к любому скрещиванию холоднокровных и теплокровных пород. [114] Примерами являются такие породы, как ирландская тяжеловозная или кливлендская гнедая . Когда-то этот термин использовался для обозначения пород легких верховых лошадей, отличных от чистокровных или арабских, таких как лошадь морганской породы . [103]

Лошади могут спать как стоя, так и лежа. В результате адаптации к жизни в дикой природе лошади способны впадать в легкий сон, используя « аппарат для остановки » в ногах, что позволяет им дремать, не падая в обморок. [115] Лошади лучше спят, когда находятся в группах, потому что некоторые животные спят, пока другие стоят на страже, высматривая хищников. Лошадь, содержащаяся в одиночестве, не будет хорошо спать, потому что ее инстинкты заставляют ее постоянно следить за опасностью. [116]

В отличие от людей, лошади не спят сплошным, непрерывным периодом времени, а отдыхают много раз. Лошади проводят от четырех до пятнадцати часов в день в состоянии покоя стоя и от нескольких минут до нескольких часов в положении лежа. Общее время сна в течение 24-часового периода может варьироваться от нескольких минут до пары часов, [116] в основном короткими интервалами примерно по 15 минут каждый. [117] Говорят, что среднее время сна домашней лошади составляет 2,9 часа в день. [118]

Лошади должны лежать, чтобы достичь фазы быстрого сна . Им нужно лежать всего час или два каждые несколько дней, чтобы удовлетворить минимальные потребности в фазе быстрого сна. [116] Однако, если лошади никогда не позволять ложиться, через несколько дней она станет лишенной сна и в редких случаях может внезапно упасть в обморок, потому что она непроизвольно впадет в фазу быстрого сна, все еще стоя. [119] Это состояние отличается от нарколепсии , хотя лошади также могут страдать от этого расстройства. [120]

Лошадь приспособилась выживать в районах с открытой местностью и скудной растительностью, выживая в экосистеме, где другие крупные травоядные животные, особенно жвачные , не могли. [121] Лошади и другие непарнокопытные — непарнокопытные из отряда Perissodactyla , группы млекопитающих, доминирующих в третичный период. В прошлом этот отряд включал 14 семейств , но только три — Equidae (лошадь и родственные виды), Tapiridae ( тапир ) и Rhinocerotidae ( носороги ) — сохранились до наших дней. [122]

Самым ранним известным представителем семейства лошадиных был Hyracotherium , который жил между 45 и 55 миллионами лет назад, в период эоцена . У него было 4 пальца на каждой передней ноге и 3 пальца на каждой задней ноге. [123] Дополнительный палец на передних ногах вскоре исчез с Mesohippus , который жил от 32 до 37 миллионов лет назад. [124] Со временем дополнительные боковые пальцы уменьшались в размерах, пока не исчезли. Все, что осталось от них у современных лошадей, — это набор небольших рудиментарных костей на ноге ниже колена, [125] неофициально известных как ленточные кости. [126] Их ноги также удлинялись, когда исчезали пальцы, пока они не стали копытным животным, способным бегать с большой скоростью. [125] Примерно 5 миллионов лет назад современный Equus эволюционировал. [127] Зубы лошадиных также эволюционировали от поедания мягких тропических растений к адаптации к поеданию более сухого растительного материала, а затем к поеданию более жестких равнинных трав. Таким образом, прото-лошади превратились из лиственно-поедающих лесных жителей в травоядных жителей полузасушливых регионов по всему миру, включая степи Евразии и Великие равнины Северной Америки.

By about 15,000 years ago, Equus ferus was a widespread holarctic species. Horse bones from this time period, the late Pleistocene, are found in Europe, Eurasia, Beringia, and North America.[128] Yet between 10,000 and 7,600 years ago, the horse became extinct in North America.[129][130][131] The reasons for this extinction are not fully known, but one theory notes that extinction in North America paralleled human arrival.[132] Another theory points to climate change, noting that approximately 12,500 years ago, the grasses characteristic of a steppe ecosystem gave way to shrub tundra, which was covered with unpalatable plants.[133]

A truly wild horse is a species or subspecies with no ancestors that were ever successfully domesticated. Therefore, most "wild" horses today are actually feral horses, animals that escaped or were turned loose from domestic herds and the descendants of those animals.[134] Only two wild subspecies, the tarpan and the Przewalski's horse, survived into recorded history and only the latter survives today.

The Przewalski's horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), named after the Russian explorer Nikolai Przhevalsky, is a rare Asian animal. It is also known as the Mongolian wild horse; Mongolian people know it as the taki, and the Kyrgyz people call it a kirtag. The subspecies was presumed extinct in the wild between 1969 and 1992, while a small breeding population survived in zoos around the world. In 1992, it was reestablished in the wild by the conservation efforts of numerous zoos.[135] Today, a small wild breeding population exists in Mongolia.[136][137] There are additional animals still maintained at zoos throughout the world.

Their status as a truly wild horse was called into question when domestic horses of the 5,000-year-old Botai culture of Central Asia were found more closely related to Przewalski's horses than to E. f. caballus. The study raised the possibility that modern Przewalski's horses could be the feral descendants of the domestic Botai horses. However, it remains possible that both the Botai horses and the modern Przewalski's horses descend separately from the same ancient wild Przewalski's horse population.[138][139][140]

The tarpan or European wild horse (Equus ferus ferus) was found in Europe and much of Asia. It survived into the historical era, but became extinct in 1909, when the last captive died in a Russian zoo.[141] Thus, the genetic line was lost. Attempts have been made to recreate the tarpan,[141][142][143] which resulted in horses with outward physical similarities, but nonetheless descended from domesticated ancestors and not true wild horses.

Periodically, populations of horses in isolated areas are speculated to be relict populations of wild horses, but generally have been proven to be feral or domestic. For example, the Riwoche horse of Tibet was proposed as such,[137] but testing did not reveal genetic differences from domesticated horses.[144] Similarly, the Sorraia of Portugal was proposed as a direct descendant of the Tarpan on the basis of shared characteristics,[145][146] but genetic studies have shown that the Sorraia is more closely related to other horse breeds, and that the outward similarity is an unreliable measure of relatedness.[145][147]

Besides the horse, there are six other species of genus Equus in the Equidae family. These are the ass or donkey, Equus asinus; the mountain zebra, Equus zebra; plains zebra, Equus quagga; Grévy's zebra, Equus grevyi; the kiang, Equus kiang; and the onager, Equus hemionus.[148]

Horses can crossbreed with other members of their genus. The most common hybrid is the mule, a cross between a "jack" (male donkey) and a mare. A related hybrid, a hinny, is a cross between a stallion and a "jenny" (female donkey).[149] Other hybrids include the zorse, a cross between a zebra and a horse.[150] With rare exceptions, most hybrids are sterile and cannot reproduce.[151]

Domestication of the horse most likely took place in central Asia prior to 3500 BCE. Two major sources of information are used to determine where and when the horse was first domesticated and how the domesticated horse spread around the world. The first source is based on palaeological and archaeological discoveries; the second source is a comparison of DNA obtained from modern horses to that from bones and teeth of ancient horse remains.

The horse was domesticated by the Indo-Europeans in Eurasia.[152][153][154] The earliest archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from sites in Ukraine and Kazakhstan, dating to approximately 4000–3500 BCE.[155][156][157] However the horses domesticated at the Botai culture in Kazakhstan were Przewalski's horses and not the ancestors of modern horses.[158][159]

By 3000 BCE, the horse was completely domesticated and by 2000 BCE there was a sharp increase in the number of horse bones found in human settlements in northwestern Europe, indicating the spread of domesticated horses throughout the continent.[160] The most recent, but most irrefutable evidence of domestication comes from sites where horse remains were interred with chariots in graves of the Indo-European Sintashta and Petrovka cultures c. 2100 BCE.[161]

A 2021 genetic study suggested that most modern domestic horses descend from the lower Volga-Don region. Ancient horse genomes indicate that these populations influenced almost all local populations as they expanded rapidly throughout Eurasia, beginning about 4,200 years ago. It also shows that certain adaptations were strongly selected due to riding, and that equestrian material culture, including Sintashta spoke-wheeled chariots spread with the horse itself.[162][163]

Domestication is also studied by using the genetic material of present-day horses and comparing it with the genetic material present in the bones and teeth of horse remains found in archaeological and palaeological excavations. The variation in the genetic material shows that very few wild stallions contributed to the domestic horse,[164][165] while many mares were part of early domesticated herds.[147][166][167] This is reflected in the difference in genetic variation between the DNA that is passed on along the paternal, or sire line (Y-chromosome) versus that passed on along the maternal, or dam line (mitochondrial DNA). There are very low levels of Y-chromosome variability,[164][165] but a great deal of genetic variation in mitochondrial DNA.[147][166][167] There is also regional variation in mitochondrial DNA due to the inclusion of wild mares in domestic herds.[147][166][167][168] Another characteristic of domestication is an increase in coat color variation.[169] In horses, this increased dramatically between 5000 and 3000 BCE.[170]

Before the availability of DNA techniques to resolve the questions related to the domestication of the horse, various hypotheses were proposed. One classification was based on body types and conformation, suggesting the presence of four basic prototypes that had adapted to their environment prior to domestication.[110] Another hypothesis held that the four prototypes originated from a single wild species and that all different body types were entirely a result of selective breeding after domestication.[171] However, the lack of a detectable substructure in the horse has resulted in a rejection of both hypotheses.

Feral horses are born and live in the wild, but are descended from domesticated animals.[134] Many populations of feral horses exist throughout the world.[172][173] Studies of feral herds have provided useful insights into the behavior of prehistoric horses,[174] as well as greater understanding of the instincts and behaviors that drive horses that live in domesticated conditions.[175]

There are also semi-feral horses in many parts of the world, such as Dartmoor and the New Forest in the UK, where the animals are all privately owned but live for significant amounts of time in "wild" conditions on undeveloped, often public, lands. Owners of such animals often pay a fee for grazing rights.[176][177]

The concept of purebred bloodstock and a controlled, written breed registry has come to be particularly significant and important in modern times. Sometimes purebred horses are incorrectly or inaccurately called "thoroughbreds". Thoroughbred is a specific breed of horse, while a "purebred" is a horse (or any other animal) with a defined pedigree recognized by a breed registry.[178] Horse breeds are groups of horses with distinctive characteristics that are transmitted consistently to their offspring, such as conformation, color, performance ability, or disposition. These inherited traits result from a combination of natural crosses and artificial selection methods. Horses have been selectively bred since their domestication. An early example of people who practiced selective horse breeding were the Bedouin, who had a reputation for careful practices, keeping extensive pedigrees of their Arabian horses and placing great value upon pure bloodlines.[179] These pedigrees were originally transmitted via an oral tradition.[180]

Breeds developed due to a need for "form to function", the necessity to develop certain characteristics in order to perform a particular type of work.[181] Thus, a powerful but refined breed such as the Andalusian developed as riding horses with an aptitude for dressage.[181] Heavy draft horses were developed out of a need to perform demanding farm work and pull heavy wagons.[182] Other horse breeds had been developed specifically for light agricultural work, carriage and road work, various sport disciplines, or simply as pets.[183] Some breeds developed through centuries of crossing other breeds, while others descended from a single foundation sire, or other limited or restricted foundation bloodstock. One of the earliest formal registries was General Stud Book for Thoroughbreds, which began in 1791 and traced back to the foundation bloodstock for the breed.[184] There are more than 300 horse breeds in the world today.[185]

Worldwide, horses play a role within human cultures and have done so for millennia. Horses are used for leisure activities, sports, and working purposes. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that in 2008, there were almost 59,000,000 horses in the world, with around 33,500,000 in the Americas, 13,800,000 in Asia and 6,300,000 in Europe and smaller portions in Africa and Oceania. There are estimated to be 9,500,000 horses in the United States alone.[186] The American Horse Council estimates that horse-related activities have a direct impact on the economy of the United States of over $39 billion, and when indirect spending is considered, the impact is over $102 billion.[187] In a 2004 "poll" conducted by Animal Planet, more than 50,000 viewers from 73 countries voted for the horse as the world's 4th favorite animal.[188]

Communication between human and horse is paramount in any equestrian activity;[189] to aid this process horses are usually ridden with a saddle on their backs to assist the rider with balance and positioning, and a bridle or related headgear to assist the rider in maintaining control.[190] Sometimes horses are ridden without a saddle,[191] and occasionally, horses are trained to perform without a bridle or other headgear.[192] Many horses are also driven, which requires a harness, bridle, and some type of vehicle.[193]

Historically, equestrians honed their skills through games and races. Equestrian sports provided entertainment for crowds and honed the excellent horsemanship that was needed in battle. Many sports, such as dressage, eventing, and show jumping, have origins in military training, which were focused on control and balance of both horse and rider. Other sports, such as rodeo, developed from practical skills such as those needed on working ranches and stations. Sport hunting from horseback evolved from earlier practical hunting techniques.[189] Horse racing of all types evolved from impromptu competitions between riders or drivers. All forms of competition, requiring demanding and specialized skills from both horse and rider, resulted in the systematic development of specialized breeds and equipment for each sport. The popularity of equestrian sports through the centuries has resulted in the preservation of skills that would otherwise have disappeared after horses stopped being used in combat.[189]

Horses are trained to be ridden or driven in a variety of sporting competitions. Examples include show jumping, dressage, three-day eventing, competitive driving, endurance riding, gymkhana, rodeos, and fox hunting.[194] Horse shows, which have their origins in medieval European fairs, are held around the world. They host a huge range of classes, covering all of the mounted and harness disciplines, as well as "In-hand" classes where the horses are led, rather than ridden, to be evaluated on their conformation. The method of judging varies with the discipline, but winning usually depends on style and ability of both horse and rider.[195]Sports such as polo do not judge the horse itself, but rather use the horse as a partner for human competitors as a necessary part of the game. Although the horse requires specialized training to participate, the details of its performance are not judged, only the result of the rider's actions—be it getting a ball through a goal or some other task.[196] Examples of these sports of partnership between human and horse include jousting, in which the main goal is for one rider to unseat the other,[197] and buzkashi, a team game played throughout Central Asia, the aim being to capture a goat carcass while on horseback.[196]

Horse racing is an equestrian sport and major international industry, watched in almost every nation of the world. There are three types: "flat" racing; steeplechasing, i.e. racing over jumps; and harness racing, where horses trot or pace while pulling a driver in a small, light cart known as a sulky.[198] A major part of horse racing's economic importance lies in the gambling associated with it.[199]

There are certain jobs that horses do very well, and no technology has yet developed to fully replace them. For example, mounted police horses are still effective for certain types of patrol duties and crowd control.[200] Cattle ranches still require riders on horseback to round up cattle that are scattered across remote, rugged terrain.[201] Search and rescue organizations in some countries depend upon mounted teams to locate people, particularly hikers and children, and to provide disaster relief assistance.[202] Horses can also be used in areas where it is necessary to avoid vehicular disruption to delicate soil, such as nature reserves. They may also be the only form of transport allowed in wilderness areas. Horses are quieter than motorized vehicles. Law enforcement officers such as park rangers or game wardens may use horses for patrols, and horses or mules may also be used for clearing trails or other work in areas of rough terrain where vehicles are less effective.[203]

Although machinery has replaced horses in many parts of the world, an estimated 100 million horses, donkeys and mules are still used for agriculture and transportation in less developed areas. This number includes around 27 million working animals in Africa alone.[204] Some land management practices such as cultivating and logging can be efficiently performed with horses. In agriculture, less fossil fuel is used and increased environmental conservation occurs over time with the use of draft animals such as horses.[205][206] Logging with horses can result in reduced damage to soil structure and less damage to trees due to more selective logging.[207]

Horses have been used in warfare for most of recorded history. The first archaeological evidence of horses used in warfare dates to between 4000 and 3000 BCE,[208] and the use of horses in warfare was widespread by the end of the Bronze Age.[209][210] Although mechanization has largely replaced the horse as a weapon of war, horses are still seen today in limited military uses, mostly for ceremonial purposes, or for reconnaissance and transport activities in areas of rough terrain where motorized vehicles are ineffective. Horses have been used in the 21st century by the Janjaweed militias in the War in Darfur.[211]

Modern horses are often used to reenact many of their historical work purposes. Horses are used, complete with equipment that is authentic or a meticulously recreated replica, in various live action historical reenactments of specific periods of history, especially recreations of famous battles.[212] Horses are also used to preserve cultural traditions and for ceremonial purposes. Countries such as the United Kingdom still use horse-drawn carriages to convey royalty and other VIPs to and from certain culturally significant events.[213] Public exhibitions are another example, such as the Budweiser Clydesdales, seen in parades and other public settings, a team of draft horses that pull a beer wagon similar to that used before the invention of the modern motorized truck.[214]

Horses are frequently used in television, films and literature. They are sometimes featured as a major character in films about particular animals, but also used as visual elements that assure the accuracy of historical stories.[215] Both live horses and iconic images of horses are used in advertising to promote a variety of products.[216] The horse frequently appears in coats of arms in heraldry, in a variety of poses and equipment.[217] The mythologies of many cultures, including Greco-Roman, Hindu, Islamic, and Germanic, include references to both normal horses and those with wings or additional limbs, and multiple myths also call upon the horse to draw the chariots of the Moon and Sun.[218] The horse also appears in the 12-year cycle of animals in the Chinese zodiac related to the Chinese calendar.[219]

Horses serve as the inspiration for many modern automobile names and logos, including the Ford Pinto, Ford Bronco, Ford Mustang, Hyundai Equus, Hyundai Pony, Mitsubishi Starion, Subaru Brumby, Mitsubishi Colt/Dodge Colt, Pinzgauer, Steyr-Puch Haflinger, Pegaso, Porsche, Rolls-Royce Camargue, Ferrari, Carlsson, Kamaz, Corre La Licorne, Iran Khodro, Eicher, and Baojun.[220][221][222] Indian TVS Motor Company also uses a horse on their motorcycles & scooters.

People of all ages with physical and mental disabilities obtain beneficial results from an association with horses. Therapeutic riding is used to mentally and physically stimulate disabled persons and help them improve their lives through improved balance and coordination, increased self-confidence, and a greater feeling of freedom and independence.[223] The benefits of equestrian activity for people with disabilities has also been recognized with the addition of equestrian events to the Paralympic Games and recognition of para-equestrian events by the International Federation for Equestrian Sports (FEI).[224] Hippotherapy and therapeutic horseback riding are names for different physical, occupational, and speech therapy treatment strategies that use equine movement. In hippotherapy, a therapist uses the horse's movement to improve their patient's cognitive, coordination, balance, and fine motor skills, whereas therapeutic horseback riding uses specific riding skills.[225]

Horses also provide psychological benefits to people whether they actually ride or not. "Equine-assisted" or "equine-facilitated" therapy is a form of experiential psychotherapy that uses horses as companion animals to assist people with mental illness, including anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, mood disorders, behavioral difficulties, and those who are going through major life changes.[226] There are also experimental programs using horses in prison settings. Exposure to horses appears to improve the behavior of inmates and help reduce recidivism when they leave.[227]

Horses are raw material for many products made by humans throughout history, including byproducts from the slaughter of horses as well as materials collected from living horses.

Products collected from living horses include mare's milk, used by people with large horse herds, such as the Mongols, who let it ferment to produce kumis.[228] Horse blood was once used as food by the Mongols and other nomadic tribes, who found it a convenient source of nutrition when traveling. Drinking their own horses' blood allowed the Mongols to ride for extended periods of time without stopping to eat.[228] The drug Premarin is a mixture of estrogens extracted from the urine of pregnant mares (pregnant mares' urine), and was previously a widely used drug for hormone replacement therapy.[229] The tail hair of horses can be used for making bows for string instruments such as the violin, viola, cello, and double bass.[230]

Horse meat has been used as food for humans and carnivorous animals throughout the ages. Approximately 5 million horses are slaughtered each year for meat worldwide.[231] It is eaten in many parts of the world, though consumption is taboo in some cultures,[232] and a subject of political controversy in others.[233] Horsehide leather has been used for boots, gloves, jackets,[234] baseballs,[235] and baseball gloves. Horse hooves can also be used to produce animal glue.[236] Horse bones can be used to make implements.[237] Specifically, in Italian cuisine, the horse tibia is sharpened into a probe called a spinto, which is used to test the readiness of a (pig) ham as it cures.[238] In Asia, the saba is a horsehide vessel used in the production of kumis.[239]

Horses are grazing animals, and their major source of nutrients is good-quality forage from hay or pasture.[240] They can consume approximately 2% to 2.5% of their body weight in dry feed each day. Therefore, a 450-kilogram (990 lb) adult horse could eat up to 11 kilograms (24 lb) of food.[241] Sometimes, concentrated feed such as grain is fed in addition to pasture or hay, especially when the animal is very active.[242] When grain is fed, equine nutritionists recommend that 50% or more of the animal's diet by weight should still be forage.[243]

Horses require a plentiful supply of clean water, a minimum of 38 to 45 litres (10 to 12 US gal) per day.[244] Although horses are adapted to live outside, they require shelter from the wind and precipitation, which can range from a simple shed or shelter to an elaborate stable.[245]

Horses require routine hoof care from a farrier, as well as vaccinations to protect against various diseases, and dental examinations from a veterinarian or a specialized equine dentist.[246] If horses are kept inside in a barn, they require regular daily exercise for their physical health and mental well-being.[247] When turned outside, they require well-maintained, sturdy fences to be safely contained.[248] Regular grooming is also helpful to help the horse maintain good health of the hair coat and underlying skin.[249]

As of 2019, there are around 17 million horses in the world. Healthy body temperature for adult horses is in the range between 37.5 and 38.5 °C (99.5 and 101.3 °F), which they can maintain while ambient temperatures are between 5 and 25 °C (41 and 77 °F). However, strenuous exercise increases core body temperature by 1 °C (1.8 °F)/minute, as 80% of the energy used by equine muscles is released as heat. Along with bovines and primates, equines are the only animal group which use sweating as their primary method of thermoregulation: in fact, it can account for up to 70% of their heat loss, and horses sweat three times more than humans while undergoing comparably strenuous physical activity. Unlike humans, this sweat is created not by eccrine glands but by apocrine glands.[251] In hot conditions, horses during three hours of moderate-intersity exercise can lose 30 to 35 L of water and 100g of sodium, 198 g of choloride and 45 g of potassium.[251] In another difference from humans, their sweat is hypertonic, and contains a protein called latherin,[252] which enables it to spread across their body easier, and to foam, rather than to drip off. These adaptations are partly to compensate for their lower body surface-to-mass ratio, which makes it more difficult for horses to passively radiate heat. Yet, prolonged exposure to very hot and/or humid conditions will lead to consequences such as anhidrosis, heat stroke, or brain damage, potentially culminating in death if not addressed with measures like cold water applications. Additionally, around 10% of incidents associated with horse transport have been attributed to heat stress. These issues are expected to worsen in the future.[250]

African horse sickness (AHS) is a viral illness with a mortality close to 90% in horses, and 50% in mules. A midge, Culicoides imicola, is the primary vector of AHS, and its spread is expected to benefit from climate change.[253] The spillover of Hendra virus from its flying fox hosts to horses is also likely to increase, as future warming would expand the hosts' geographic range. It has been estimated that under the "moderate" and high climate change scenarios, RCP4.5 and RCP8.5, the number of threatened horses would increase by 110,000 and 165,000, respectively, or by 175 and 260%.[254]