В Америке коренные народы включают доколумбовых жителей континента до европейского поселения в 15 веке, а также этнические группы, которые идентифицируют себя с доколумбовым населением континента как таковым. [37] Эти популяции демонстрируют значительное разнообразие; некоторые коренные народы исторически были охотниками-собирателями , в то время как другие занимались сельским хозяйством и аквакультурой . Различные коренные общества развивали сложные социальные структуры, включая монументальную архитектуру до контакта, организованные города, города-государства, вождества , государства, королевства, республики, конфедерации и империи. [38] Эти общества обладали различными уровнями знаний в таких областях, как инженерия, архитектура, математика, астрономия, письмо, физика, медицина, сельское хозяйство, ирригация, геология, горное дело, металлургия, скульптура и ювелирное дело.

Коренные народы продолжают населять многие регионы Америки, со значительным населением в таких странах, как Боливия , Канада , Чили , Колумбия , Эквадор , Гватемала, Мексика , Перу и Соединенные Штаты . Существует по меньшей мере тысяча различных языков коренных народов, на которых говорят по всей Америке, и только в США насчитывается 574 федерально признанных племени . Некоторые языки, включая кечуа , аравак , аймара , гуарани , майя и науатль , имеют миллионы носителей и признаны официальными правительствами Боливии, Перу, Парагвая и Гренландии. Коренные народы, независимо от того, проживают ли они в сельской местности или в городах, часто сохраняют аспекты своей культурной практики, включая религию, социальную организацию и методы ведения хозяйства . Со временем эти культуры развивались, сохраняя традиционные обычаи и приспосабливаясь к современным потребностям. Некоторые коренные народы остаются относительно изолированными от западной культуры , а некоторые до сих пор считаются неконтактными народами . [39]

В Америке также проживают миллионы людей смешанного коренного, европейского, а иногда и африканского или азиатского происхождения, которых в испаноязычных странах исторически называют метисами . [40] [41] Во многих латиноамериканских странах люди частично коренного происхождения составляют большинство или значительную часть населения, особенно в Центральной Америке , Мексике, Перу, Боливии, Эквадоре, Колумбии, Венесуэле, Чили и Парагвае. [42] [43] [44] Согласно оценкам этнической культурной идентификации, метисы превосходят по численности коренные народы в большинстве испаноязычных стран. Однако, поскольку коренные общины в Америке определяются культурной идентификацией и родством, а не происхождением или расой , метисы, как правило, не учитываются среди коренного населения, если только они не говорят на языке коренного народа или не идентифицируют себя с определенной культурой коренного народа. [45] Кроме того, многие лица полностью коренного происхождения, которые не следуют традициям коренных народов или не говорят на языке коренных народов, были классифицированы или идентифицируют себя как метисы из-за ассимиляции в доминирующей испаноязычной культуре . В последние годы самоидентифицирующее коренное население во многих странах увеличилось, поскольку люди возвращают себе свое наследие на фоне растущих движений коренных народов за самоопределение и социальную справедливость . [46]

_2007.jpg/440px-Navajo_(young_boy)_2007.jpg)

Термин « индеец » впервые был использован Христофором Колумбом , который, во время своих поисков Индии , думал, что прибыл в Ост-Индию . [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52]

Острова стали известны как « Вест-Индия » (или « Антильские острова »), название, которое до сих пор используется для описания островов. Это привело к общему термину «Индия» и «индейцы» ( исп .: indios ; португальский : índios ; французский : indiens ; голландский : indianen ) для коренных жителей, что подразумевало некое этническое или культурное единство среди коренных народов Америки. Эта объединяющая концепция, кодифицированная в законодательстве, религии и политике, изначально не была принята бесчисленными группами самих коренных народов, но с тех пор была принята или терпима многими в течение последних двух столетий. [53] Термин «индеец», как правило, не включает культурно и лингвистически отличные коренные народы арктических регионов Америки, включая алеутов , инуитов или юпик . Эти народы пришли на континент в качестве второй, более поздней волны миграции несколько тысяч лет спустя и имеют гораздо более недавние генетические и культурные сходства с коренными народами Сибири . Однако эти группы тем не менее считаются «коренными народами Америки». [54]

Термин «америндеец» , являющийся производным от «американский индеец», был придуман в 1902 году Американской антропологической ассоциацией . Он был спорным с момента своего создания. Он был немедленно отвергнут некоторыми ведущими членами Ассоциации, и, хотя был принят многими, он никогда не был общепринятым. [55] Хотя он никогда не был популярен в самих коренных общинах, он остается предпочтительным термином среди некоторых антропологов, особенно в некоторых частях Канады и англоговорящих странах Карибского бассейна . [56] [57] [58] [59]

« Коренные народы Канады » используется как собирательное название для первых наций , инуитов и метисов . [60] [61] Термин «аборигенные народы » как собирательное существительное (также описывающее первые нации, инуитов и метисов) — это особый художественный термин, используемый в некоторых юридических документах, включая Конституционный акт 1982 года . [62] Со временем, по мере изменения общественного восприятия и отношений между правительством и коренными народами, многие исторические термины изменили определения или были заменены, поскольку вышли из употребления. [63] Использование термина «индеец» не одобряется, поскольку оно представляет собой навязывание и ограничение коренных народов и культур со стороны канадского правительства. [63] Термины «коренной» и « эскимос », как правило, считаются неуважительными (в Канаде), и поэтому редко используются, если только это не требуется специально. [64] Хотя «коренные народы» является предпочтительным термином, многие люди или сообщества могут предпочесть описывать свою идентичность, используя другой термин. [63] [64]

Например, метисов Канады можно сравнить с коренными европейцами смешанной расы метисами (или кабокло в Бразилии) латиноамериканской Америки , которые, учитывая их большую численность (в большинстве стран Латинской Америки они составляют либо абсолютное большинство, либо относительно большую часть, либо, по крайней мере, значительное меньшинство), в значительной степени идентифицируют себя как новую этническую группу, отличную как от европейцев, так и от коренных народов, но при этом по-прежнему считающую себя подгруппой латиноамериканского или бразильского народа европейского происхождения по культуре и этнической принадлежности ( ср. ладино ).

Среди испаноговорящих стран indígenas или pueblos indígenas («коренные народы») является распространенным термином, хотя nativos или pueblos nativos («коренные народы») также можно услышать; более того, aborigen («абориген») используется в Аргентине , а pueblos originarios («исконные народы») распространено в Чили . В Бразилии indígenas и povos originários («коренные народы») являются распространенными формально звучащими обозначениями, в то время как índio («индеец») по-прежнему является более часто употребляемым термином (существительное для южноазиатской национальности — indiano ), но за последние 10 лет оно считается оскорбительным и уничижительным. [ необходима цитата ] Aborígene и nativo редко используются в Бразилии в контексте, специфичном для коренных народов (например, aborígene обычно понимается как этноним коренных австралийцев ). Испанские и португальские эквиваленты Indian , тем не менее, могут использоваться для обозначения любого охотника-собирателя или чистокровного коренного человека, особенно на континентах, отличных от Европы или Африки, например, indios filipinos . [ необходима цитата ]

Коренные народы Соединенных Штатов обычно известны как коренные американцы , индейцы, а также коренные жители Аляски . [ необходимо разъяснение ] Термин «индеец» все еще используется в некоторых общинах и остается в официальных названиях многих учреждений и предприятий в Индейской стране . [65]

Различные нации, племена и группы коренных народов Америки имеют различные предпочтения в терминологии для себя. [66] [ нужна страница ] Хотя существуют региональные и поколенческие различия, в которых для коренных народов в целом предпочтительны общие термины, в целом большинство коренных народов предпочитают, чтобы их идентифицировали по названию их конкретной нации, племени или группы. [66] [67]

Ранние поселенцы часто принимали термины, которые некоторые племена использовали друг для друга, не понимая, что это были уничижительные термины, используемые врагами. При обсуждении более широких подгрупп народов, наименование часто основывалось на общем языке, регионе или исторических отношениях. [68] Многие английские экзонимы использовались для обозначения коренных народов Америки. Некоторые из этих названий были основаны на иностранных терминах, используемых ранними исследователями и колонистами, в то время как другие возникли в результате попыток колонистов перевести или транслитерировать эндонимы с местных языков. Другие термины возникли в периоды конфликтов между колонистами и коренными народами. [69]

С конца 20-го века коренные народы в Америке стали более открыто заявлять о том, как они хотят, чтобы к ним обращались, настаивая на запрете использования терминов, которые широко считаются устаревшими, неточными или расистскими . Во второй половине 20-го века и на подъеме движения за права индейцев федеральное правительство Соединенных Штатов ответило предложением использовать термин « коренной американец », чтобы признать главенство права коренных народов на владение землей в стране. [70] Как и следовало ожидать, среди людей более 400 различных культур только в США не все люди, которых предполагается описывать этим термином, согласились с его использованием или приняли его. Ни одна единая конвенция о наименовании групп не была принята всеми коренными народами в Америке. Большинство предпочитают, чтобы к ним обращались как к людям их племени или нации, когда речь не идет о коренных американцах/американских индейцах в целом. [71]

Начиная с 1970-х годов слово «коренной», которое пишется с заглавной буквы, когда речь идет о людях, постепенно стало предпочтительным обобщающим термином. Использование заглавных букв означает признание того, что коренные народы имеют культуру и общество, которые равны европейцам, африканцам и азиатам. [67] [72] Это недавно было признано в AP Stylebook . [73] Некоторые считают неправильным называть коренных жителей «коренными американцами» или добавлять к этому термину какую-либо колониальную национальность, поскольку коренные культуры существовали до европейской колонизации. У коренных групп есть территориальные претензии, которые отличаются от современных национальных и международных границ, и когда их называют частью страны, их традиционные земли не признаются. Некоторые, у кого есть письменные руководства, считают более уместным описывать коренного человека как «живущего в» или «из» Америки, а не называть его «американцем»; или просто называть его «коренным» без какого-либо добавления колониального государства. [74] [75]

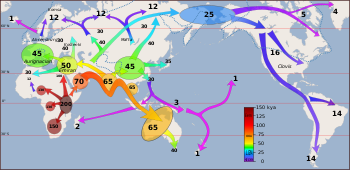

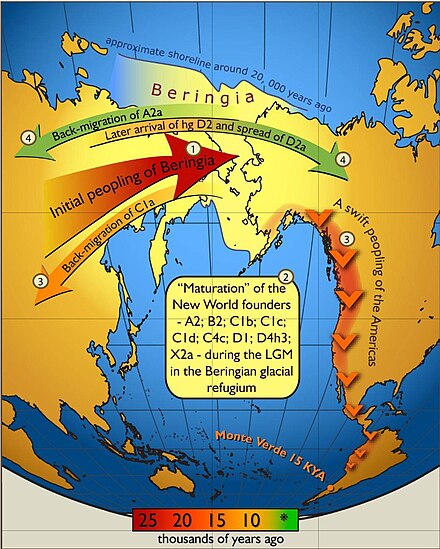

Заселение Америки началось, когда палеолитические охотники-собиратели ( палеоиндейцы ) проникли в Северную Америку из североазиатской мамонтовой степи через перешеек Берингии , который образовался между северо-восточной Сибирью и западной Аляской из-за понижения уровня моря во время последнего ледникового максимума (26 000–19 000 лет назад). [77] Эти популяции расширились к югу от Лаврентийского ледникового щита и быстро распространились на юг, заняв как Северную, так и Южную Америку 12 000–14 000 лет назад. [78] [79] [80] [81] [82] Самые ранние популяции в Америке, появившиеся примерно 10 000 лет назад, известны как палеоиндейцы . Коренные народы Америки были связаны с сибирскими популяциями по предполагаемым языковым факторам , распределению групп крови и генетическому составу , отраженному молекулярными данными, такими как ДНК . [83] [84]

Хотя существует общее согласие, что Америка была впервые заселена выходцами из Азии, схема миграции и место(а) происхождения в Евразии народов, которые мигрировали в Америку, остаются неясными. [79] Традиционная теория заключается в том, что древние берингийцы переселились, когда уровень моря значительно понизился из-за четвертичного оледенения , [85] [86] следуя за стадами ныне вымершей плейстоценовой мегафауны по свободным ото льда коридорам , которые тянулись между Лаврентийским и Кордильерским ледниковыми щитами. [87] Другой предложенный маршрут заключается в том, что они пешком или на лодках мигрировали вдоль побережья Тихого океана в Южную Америку до Чили . [88] Любые археологические свидетельства прибрежной оккупации во время последнего ледникового периода теперь были бы скрыты повышением уровня моря , до ста метров с тех пор. [89]

Точная дата заселения Америки — давно открытый вопрос. Хотя достижения археологии , геологии плейстоцена , физической антропологии и анализа ДНК постепенно проливают больше света на эту тему, важные вопросы остаются нерешенными. [90] [91] «Теория первых Кловис» относится к гипотезе о том, что культура Кловис представляет собой самое раннее присутствие человека в Америке около 13 000 лет назад. [92] Накопились свидетельства существования докловисских культур , которые отодвинули возможную дату первого заселения Америки. [93] [ 94] [95] [96] Ученые в целом считают, что люди достигли Северной Америки к югу от ледникового щита Лаврентида в какой-то момент между 15 000 и 20 000 лет назад. [90] [93] [97] [98] [99] [100] Некоторые новые спорные археологические свидетельства предполагают возможность того, что прибытие человека в Америку могло произойти до последнего ледникового максимума, более 20 000 лет назад. [93] [101] [102] [103] [104] [105]

Хотя технически этот термин относится к эпохе до путешествий Христофора Колумба с 1492 по 1504 год, на практике этот термин обычно включает в себя историю коренных культур до того, как европейцы либо завоевали их, либо оказали на них значительное влияние. [109] Термин «доколумбовый» особенно часто используется в контексте обсуждения доконтактных мезоамериканских коренных обществ : ольмеков , тольтеков , теотиуаканских , сапотеков , миштеков , ацтеков и майя , а также сложных культур Анд : империи инков , культуры моче , конфедерации муисков и каньяри .

Доколумбовая эпоха относится ко всем периодам в истории и предыстории Америки до появления значительных европейских и африканских влияний на американских континентах, охватывая время первоначального прибытия в верхнем палеолите до европейской колонизации в течение раннего современного периода . [110] Цивилизация Норте-Чико (на территории современного Перу) является одной из определяющих шести изначальных цивилизаций мира, возникших независимо примерно в то же время, что и Египет . [111] [112] Многие более поздние доколумбовые цивилизации достигли большой сложности, с отличительными чертами, которые включали постоянные или городские поселения, сельское хозяйство, инженерию, астрономию, торговлю, гражданскую и монументальную архитектуру и сложные общественные иерархии . Некоторые из этих цивилизаций давно исчезли ко времени первых значительных европейских и африканских прибытий (приблизительно конец 15-го - начало 16-го веков) и известны только по устной истории и благодаря археологическим исследованиям. Другие были современниками периода контактов и колонизации и были задокументированы в исторических записях того времени. Некоторые, такие как народы майя, ольмеки, миштеки, ацтеки и науа , имели свои письменные языки и записи. Однако европейские колонисты того времени работали над устранением нехристианских верований и сожгли многие доколумбовы письменные записи. Лишь несколько документов остались скрытыми и сохранились, оставив современным историкам проблески древней культуры и знаний.

Согласно как коренным, так и европейским отчетам и документам, американские цивилизации до и во время встречи с европейцами достигли большой сложности и многих достижений. [113] Например, ацтеки построили один из крупнейших городов в мире, Теночтитлан (историческое место того, что станет Мехико ), с предполагаемым населением в 200 000 человек для самого города и населением около пяти миллионов для расширенной империи. [114] Для сравнения, крупнейшими европейскими городами в 16 веке были Константинополь и Париж с 300 000 и 200 000 жителей соответственно. [115] Население Лондона, Мадрида и Рима едва превышало 50 000 человек. В 1523 году, как раз во время испанского завоевания, все население страны Англии составляло чуть менее трех миллионов человек. [116] Этот факт говорит об уровне сложности, сельского хозяйства, правительственных процедур и верховенства закона, которые существовали в Теночтитлане, необходимом для управления таким большим населением. Коренные цивилизации также продемонстрировали впечатляющие достижения в астрономии и математике, включая самый точный календарь в мире. [ необходима цитата ] Одомашнивание кукурузы или маиса потребовало тысяч лет селективного разведения, и постоянное выращивание множества сортов осуществлялось с планированием и отбором, как правило, женщинами.

Мифы о сотворении мира инуитов, юпиков, алеутов и коренных народов рассказывают о различных истоках их народов. Некоторые из них были «всегда там» или были созданы богами или животными, некоторые мигрировали из определенной точки компаса , а другие пришли «из-за океана». [117]

Европейская колонизация Америки кардинально изменила жизнь и культуру коренных народов, проживавших там. Хотя точная численность населения Америки до колонизации неизвестна, ученые подсчитали, что коренное население сократилось на 80–90 % в течение первых столетий европейской колонизации. Большинство ученых оценивают численность населения до колонизации примерно в 50 миллионов человек, другие же утверждают, что эта цифра составляет 100 миллионов. Оценки достигают 145 миллионов. [118] [119] [120]

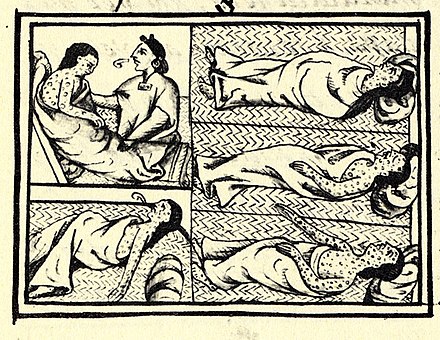

Эпидемии опустошали Америку такими болезнями, как оспа , корь и холера , которые первые колонисты привезли из Европы. Распространение инфекционных заболеваний изначально было медленным, так как большинство европейцев не были активно или явно инфицированы из-за унаследованного иммунитета от поколений воздействия этих болезней в Европе. Это изменилось, когда европейцы начали торговлю людьми в огромных количествах рабов из Западной и Центральной Африки в Америке. Как и коренные народы, эти африканцы, недавно подвергшиеся воздействию европейских болезней, не имели какой-либо унаследованной устойчивости к болезням Европы. В 1520 году африканец, зараженный оспой, прибыл на Юкатан. К 1558 году болезнь распространилась по всей Южной Америке и достигла бассейна Платы. [121] Насилие колонистов по отношению к коренным народам ускорило гибель людей. Европейские колонисты совершали массовые убийства коренных народов и порабощали их. [122] [123] [124] По данным Бюро переписи населения США (1894 г.), в ходе североамериканских индейских войн XIX века погибло около 19 000 европейцев и 30 000 коренных американцев, а общее число погибших среди коренных американцев оценивается в 45 000 человек. [125]

Первая группа коренных народов, с которой столкнулся Колумб, 250 000 таино с Эспаньолы , представляли доминирующую культуру на Больших Антильских островах и Багамах. В течение тридцати лет около 70% таино умерли. [126] У них не было иммунитета к европейским болезням, поэтому вспышки кори и оспы опустошили их популяцию. [127] Одна из таких вспышек произошла в лагере рабов-африканцев, где оспа распространилась на соседнее население таино и сократила их численность на 50%. [121] Ужесточение наказания таино за восстание против принудительного труда, несмотря на меры, принятые энкомьендой , которые включали религиозное образование и защиту от враждующих племен, [128] в конечном итоге привело к последнему великому восстанию таино (1511–1529).

После многих лет жестокого обращения таино начали проявлять суицидальное поведение: женщины делали аборты или убивали своих младенцев, а мужчины прыгали со скал или глотали необработанную маниоку , сильный яд. [126] В конце концов, касик таино по имени Энрикильо сумел продержаться в горном хребте Баоруко в течение тринадцати лет, нанеся серьезный ущерб испанским, карибским плантациям и их индейским вспомогательным войскам . [129] [ проверка не удалась ] Узнав о серьезности восстания, император Карл V (также король Испании) послал капитана Франсиско Баррионуэво для переговоров о мирном договоре с постоянно растущим числом мятежников. Два месяца спустя, после консультации с Ауденцией Санто-Доминго, Энрикильо предложили любую часть острова, чтобы жить в мире.

Законы Бургоса 1512–1513 годов были первым кодифицированным сводом законов, регулирующих поведение испанских поселенцев в Америке, особенно в отношении коренных народов. Законы запрещали жестокое обращение с ними и одобряли их обращение в католичество . [130] Испанской короне было трудно обеспечить соблюдение этих законов в отдаленных колониях.

Эпидемические заболевания были основной причиной сокращения численности населения коренных народов. [131] [132] После первоначального контакта с европейцами и африканцами болезни Старого Света стали причиной смерти от 90 до 95% коренного населения Нового Света в последующие 150 лет. [133] Оспа убила от одной трети до половины коренного населения Эспаньолы в 1518 году . [134] [135] Убив правителя инков Уайна Капака , оспа вызвала гражданскую войну инков 1529–1532 годов. Оспа была только первой эпидемией. Тиф (вероятно) в 1546 году, грипп и оспа вместе в 1558 году, снова оспа в 1589 году, дифтерия в 1614 году и корь в 1618 году — все это опустошило остатки культуры инков.

Оспа убила миллионы коренных жителей Мексики. [136] [137] Непреднамеренно завезенная в Веракрус с прибытием Панфило де Нарваэса 23 апреля 1520 года, оспа опустошила Мексику в 1520-х годах, [138] возможно, убив более 150 000 человек в одном только Теночтитлане (сердце империи ацтеков) и способствуя победе Эрнана Кортеса над империей ацтеков в Теночтитлане (современный Мехико) в 1521 году. [ необходима цитата ] [121]

Существует множество факторов, объясняющих, почему коренные народы понесли такие огромные потери от афро-евразийских болезней. Многие болезни Старого Света, такие как коровья оспа, передаются от одомашненных животных, которые не являются коренными для Америки. Европейское население приспособилось к этим болезням и выработало устойчивость на протяжении многих поколений. Многие из болезней Старого Света, которые были завезены в Америку, были болезнями, такими как желтая лихорадка , которые были относительно управляемы, если заразиться в детстве, но были смертельными, если заразиться во взрослом возрасте. Дети часто могли пережить болезнь, что приводило к иммунитету к болезни на всю оставшуюся жизнь. Но контакт со взрослым населением без этого детского или унаследованного иммунитета привел бы к тому, что эти болезни оказались бы фатальными. [121] [139]

Колонизация Карибского моря привела к уничтожению араваков Малых Антильских островов . Их культура была уничтожена к 1650 году. К 1550 году выжило только 500 человек, хотя родословная продолжилась до современного населения. В Амазонии коренные сообщества пережили и продолжают страдать от столетий колонизации и геноцида. [140]

Контакт с европейскими болезнями, такими как оспа и корь, убил от 50 до 67 процентов коренного населения Северной Америки в первые сто лет после прибытия европейцев. [141] Около 90 процентов коренного населения около колонии Массачусетского залива умерли от оспы во время эпидемии в 1617–1619 годах. [142] В 1633 году в Форт-Оранж (Новые Нидерланды) коренные американцы подверглись воздействию оспы из-за контакта с европейцами. Как и в других местах, вирус уничтожил целые группы населения коренных американцев. [143] Он достиг озера Онтарио в 1636 году, а земель ирокезов — к 1679 году. [144] [145] В 1770-х годах оспа убила по меньшей мере 30% коренных американцев Западного побережья . [146] Эпидемия оспы в Северной Америке 1775–1782 годов и эпидемия оспы на Великих равнинах 1837 года принесли опустошение и резкое сокращение численности населения среди индейцев равнин . [147] [148] В 1832 году федеральное правительство Соединенных Штатов учредило программу вакцинации против оспы для коренных американцев ( Закон о вакцинации индейцев 1832 года ). [149]

Численность коренных народов Бразилии сократилась с доколумбовой отметки в три миллиона [150] до примерно 300 000 в 1997 году. [ сомнительно – обсудить ] [ проверка не удалась ] [151]

Испанская империя и другие европейцы повторно завезли лошадей в Америку. Некоторые из этих животных сбежали и начали размножаться и увеличивать свою численность в дикой природе. [152] Повторное завоз лошадей , вымерших в Америке более 7500 лет назад, оказало глубокое влияние на культуры коренных народов в нескольких регионах, таких как Великие равнины , Северо-Западное плато , Большой Бассейн , Аридоамерика , Гран-Чако и Южный Конус . Одомашнивая лошадей, некоторые племена добились большого успеха: лошади позволили им расширить свои территории, обмениваться большим количеством товаров с соседними племенами и легче ловить дичь , такую как бизон .

По данным Эрин Маккенны и Скотта Л. Пратта, коренное население Америки в конце XV века составляло 145 миллионов человек, а к концу XVII века сократилось до 15 миллионов из-за эпидемий , войн, резни, массовых изнасилований , голода и порабощения. [120]

Историческая травма коренных народов (ИТК) — это травма, которая может накапливаться на протяжении поколений и развиваться в результате исторических последствий колонизации и связана с трудностями психического и физического здоровья и сокращением численности населения. [153] ИТК влияет на многих людей множеством способов, поскольку коренное сообщество и его история разнообразны.

Во многих исследованиях (например, Whitbeck et al., 2014; [154] Brockie, 2012; Anastasio et al., 2016; [155] Clark & Winterowd, 2012; [156] Tucker et al., 2016) [157] оценивалось влияние IHT на результаты в отношении здоровья коренных народов из Соединенных Штатов и Канады. IHT — это сложный термин для стандартизации и измерения из-за огромного и изменчивого разнообразия коренных народов и их сообществ. Поэтому при изучении IHT сложно дать рабочее определение и систематически собирать данные. Многие исследования, включающие IHT, измеряют его по-разному, что затрудняет сбор данных и их целостный анализ. Это важный момент, который обеспечивает контекст для следующих исследований, которые пытаются понять связь между IHT и потенциальными неблагоприятными последствиями для здоровья.

Некоторые из методологий измерения IHT включают «Шкалу исторических потерь» (HLS), «Шкалу симптомов, связанных с историческими потерями» (HLASS) и исследования предков в школах-интернатах. [153] : 23 HLS использует формат опроса, который включает «12 видов исторических потерь», таких как потеря языка и потеря земли, и спрашивает участников, как часто они думают об этих потерях. [153] : 23 HLASS включает 12 эмоциональных реакций и спрашивает участников, что они чувствуют, когда думают об этих потерях. [153] Наконец, исследования предков в школах-интернатах спрашивают респондентов, ходили ли их родители, бабушки и дедушки, прабабушки и дедушки или «старейшины из их сообщества» в школу-интернат, чтобы понять, связана ли семейная или общественная история в школах-интернатах с негативными последствиями для здоровья. [153] : 25 В комплексном обзоре исследовательской литературы Джозеф Гоне и коллеги [153] собрали и сравнили результаты исследований, использующих эти меры IHT, относительно результатов в отношении здоровья коренных народов. Исследование определило негативные результаты в отношении здоровья, включив такие понятия, как тревожность , суицидальные мысли , попытки самоубийства , злоупотребление несколькими веществами , ПТСР , депрессия , переедание , гнев и сексуальное насилие. [153]

Связь между IHT и состояниями здоровья осложняется из-за сложной природы измерения IHT, неизвестной направленности IHT и результатов для здоровья, а также из-за того, что термин « коренные народы», используемый в различных выборках, охватывает огромную популяцию людей с кардинально разным опытом и историями. При этом некоторые исследования, такие как Bombay, Matheson и Anisman (2014), [158] , Elias et al. (2012), [159] и Pearce et al. (2008) [160], обнаружили, что респонденты из числа коренных народов, имеющие связь с интернатами, имеют больше негативных последствий для здоровья (например, мысли о самоубийстве, попытки самоубийства и депрессия), чем те, кто не имел связи с интернатами. Кроме того, респонденты из числа коренных народов с более высокими показателями HLS и HLASS имели один или несколько негативных последствий для здоровья. [153] Хотя существует множество исследований [155] [161] [156] [162] [157] , которые обнаружили связь между IHT и неблагоприятными последствиями для здоровья, ученые продолжают предполагать, что по-прежнему трудно понять влияние IHT. IHT необходимо систематически измерять. Коренные народы также необходимо рассматривать в отдельных категориях на основе схожего опыта, местоположения и происхождения, а не классифицировать как одну монолитную группу. [153]

На протяжении тысяч лет коренные народы одомашнивали, разводили и культивировали большое количество видов растений. Эти виды сейчас составляют от 50% до 60% всех выращиваемых культур во всем мире. [163] В некоторых случаях коренные народы вывели совершенно новые виды и штаммы путем искусственного отбора , как в случае одомашнивания и разведения кукурузы из диких трав теосинте в долинах южной Мексики. Многочисленные такие сельскохозяйственные продукты сохраняют свои родные названия в английском и испанском лексиконах.

Южноамериканские высокогорья стали центром раннего земледелия. Генетическое тестирование широкого спектра сортов и диких видов предполагает, что картофель имеет единое происхождение в районе южного Перу , [164] от вида в комплексе Solanum brevicaule . Более 99% всего современного культивируемого картофеля во всем мире являются потомками подвида, коренного для юго-центрального Чили , [165] Solanum tuberosum ssp. tuberosum , где он культивировался еще 10 000 лет назад. [166] [167] По словам Линды Ньюсон , «очевидно, что в доколумбовые времена некоторые группы боролись за выживание и часто страдали от нехватки продовольствия и голода , в то время как другие наслаждались разнообразным и сытным рационом». [168]

Постоянная засуха около 850 г. н. э. совпала с крахом классической цивилизации майя , а голод One Rabbit (1454 г. н. э.) стал крупной катастрофой в Мексике. [169]

Коренные народы Северной Америки начали заниматься сельским хозяйством примерно 4000 лет назад, в конце архаического периода североамериканских культур. Технологии достигли такого уровня, что керамика стала обычным явлением, а мелкомасштабная вырубка деревьев стала возможной. Одновременно с этим коренные народы архаического периода начали использовать огонь контролируемым образом. Они проводили преднамеренное сжигание растительности, чтобы имитировать эффекты естественных пожаров, которые, как правило, очищали лесные подлески. Это облегчало путешествия и способствовало росту трав и ягодных растений, которые были важны как для пищи, так и для лекарств. [170]

В долине реки Миссисипи европейцы отметили, что коренные американцы выращивали ореховые и фруктовые деревья недалеко от деревень и городов, а также свои сады и сельскохозяйственные поля. Они бы использовали предписанное выжигание подальше, в лесных и прерийных районах. [171]

Многие культуры, впервые одомашненные коренными народами, теперь производятся и используются во всем мире, в частности, кукуруза (или «зерно»), возможно, самая важная культура в мире. [172] Другие значимые культуры включают маниоку ; чиа ; тыкву (тыкву, цуккини, кабачки , желудевую тыкву , мускатную тыкву ); фасоль пинто , бобы Phaseolus , включая наиболее распространенные бобы , фасоль тепари и фасоль лима ; помидоры ; картофель ; сладкий картофель ; авокадо ; арахис ; какао-бобы (используются для приготовления шоколада ); ваниль ; клубнику ; ананасы ; перец (виды и сорта Capsicum , включая болгарский перец , халапеньо , паприку и перец чили ); семена подсолнечника ; каучук ; бразильское дерево ; чикл ; табак ; кока ; черника , клюква и некоторые виды хлопка .

Исследования современного управления окружающей средой коренных народов, включая агролесоводческие практики среди майя Ица в Гватемале, а также охоту и рыболовство среди меномини в Висконсине, предполагают, что давние «священные ценности» могут представлять собой свод устойчивых тысячелетних традиций. [173]

Многочисленные породы собак коренных американцев использовались народами Америки, такими как канадская эскимосская собака , каролинская собака и чихуахуа . Некоторые коренные народы Великих равнин использовали собак для тяги волокуш , в то время как другие, такие как талтанская медвежья собака, были выведены для охоты на более крупную дичь. Некоторые андские культуры также разводили чирибайя для выпаса лам . Подавляющее большинство коренных пород собак в Америке вымерли из-за того, что их заменили собаки европейского происхождения. [174]

Огненная собака была одомашненной разновидностью кульпео , которую разводили несколько культур на Огненной Земле , например, селькнамы и яганы . [175] Она была истреблена аргентинскими и чилийскими поселенцами из-за того, что, предположительно, представляла угрозу для домашнего скота. [176]

Несколько видов птиц, таких как индейки , мускусные утки , пуна-ибисы и неотропические бакланы , были одомашнены различными народами Мезоамерики и Южной Америки для использования в качестве домашней птицы.

В Андском регионе коренные народы одомашнивали лам и альпак для производства волокна и мяса. Лама была единственным вьючным животным в Америке до европейской колонизации.

Морские свинки были одомашнены из диких морских свинок для выращивания на мясо в Андском регионе. Морские свинки в настоящее время широко выращиваются в западном обществе в качестве домашних животных.

В Оазисамерике несколько культур выращивали алых ара, импортированных из Мезоамерики ради их перьев. [177] [178]

В цивилизации майя для производства бальче были одомашнены безжалые пчелы . [179]

Кошениль собирали цивилизациями Мезоамерики и Анд для окрашивания тканей с помощью карминовой кислоты . [180] [181] [182]

Культурные практики в Америке, по-видимому, были распространены в основном в пределах географических зон, где отдельные этнические группы перенимают общие культурные черты, схожие технологии и социальные организации. Примером такой культурной области является Мезоамерика , где тысячелетия сосуществования и совместного развития среди народов региона создали довольно однородную культуру со сложными сельскохозяйственными и социальными моделями. Другим известным примером являются североамериканские равнины, где до 19 века несколько народов разделяли черты кочевых охотников-собирателей, основанные в основном на охоте на бизонов.

Языки североамериканских индейцев были классифицированы на 56 групп или языковых групп, в которых, можно сказать, сосредоточены разговорные языки племен. В связи с речью можно упомянуть язык жестов, который был высоко развит в некоторых частях этой области. Не меньший интерес представляет собой рисуночное письмо, особенно хорошо развитое среди чиппева и делаваров . [183]

Начиная с 1-го тысячелетия до н. э., доколумбовые культуры в Мезоамерике разработали несколько систем письма коренных народов (независимо от какого-либо влияния систем письма, существовавших в других частях мира). Блок Каскахаль , возможно, является самым ранним известным примером в Америке того, что может быть обширным письменным текстом. Табличка с иероглифами ольмеков была косвенно датирована (по керамическим черепкам, найденным в том же контексте) приблизительно 900 годом до н. э., что примерно в то же время, когда оккупация ольмеков в Сан-Лоренсо-Теночтитлане начала ослабевать. [184]

Система письма майя была логосиллабической (комбинация фонетических слоговых символов и логограмм ). Это единственная доколумбовая система письма, которая, как известно, полностью представляла разговорный язык своего сообщества. Она имеет более тысячи различных глифов , но некоторые из них являются вариациями одного и того же знака или имеют одинаковое значение, многие появляются только редко или в определенных местах, не более пятисот использовались в любой момент времени, и из них, кажется, только около двухсот (включая вариации) представляли определенную фонему или слог. [185] [186] [187]

Система письма сапотеков , одна из самых ранних в Америке, [188] была логографической и, предположительно, слоговой . [188] Остатки письма сапотеков сохранились в надписях на некоторых монументальных архитектурных сооружениях того периода, но сохранилось так мало надписей, что трудно полностью описать систему письма. Самый старый пример письма сапотеков, датируемый примерно 600 годом до н. э., находится на памятнике, который был обнаружен в Сан-Хосе-Моготе . [189] [ необходима полная цитата ]

Ацтекские кодексы (единственное число кодекс ) — это книги, написанные ацтеками доколумбовой и колониальной эпохи . Эти кодексы являются одними из лучших первоисточников для описания культуры ацтеков . Доколумбовые кодексы в основном иллюстрированы; они не содержат символов, которые представляют устную или письменную речь. [190] Напротив, кодексы колониальной эпохи содержат не только ацтекские пиктограммы , но и письмена, использующие латинский алфавит на нескольких языках: классический науатль , испанский и иногда латынь .

Испанские нищие в шестнадцатом веке научили писцов коренных народов в своих общинах писать на своих языках латинскими буквами, и существует большое количество документов местного уровня на языках науатль , сапотек , миштек и юкатек майя с колониальной эпохи, многие из которых были частью судебных исков и других юридических вопросов. Хотя изначально испанцы обучали писцов коренных народов алфавитному письму, традиция стала самоподдерживающейся на местном уровне. [191] Испанская корона собирала такую документацию, и современные испанские переводы были сделаны для судебных дел. Ученые перевели и проанализировали эти документы в так называемой Новой филологии , чтобы написать истории коренных народов с точки зрения коренных народов. [192] [ нужна страница ]

Вигваасабак — свитки из бересты , на которых народ оджибве ( анишинабе ) писал сложные геометрические узоры и фигуры, — также можно считать формой письма, как и иероглифы микмаков .

Слоговое письмо аборигенов, или просто силлабика , представляет собой семейство абугид, используемых для записи некоторых языков коренных народов алгонкинской , инуитской и атабаскской языковых семей.

Музыка коренных народов может различаться в зависимости от культуры, однако есть и существенные сходства. Традиционная музыка часто вращается вокруг игры на барабанах и пения. Трещотки , трещотки и рашпили также являются популярными ударными инструментами, как исторически, так и в современных культурах. Флейты изготавливаются из речного тростника, кедра и других пород дерева. У апачей есть своего рода скрипка , а скрипки также встречаются во многих культурах коренных народов и метисов .

Музыка коренных народов Центральной Мексики и Центральной Америки, как и североамериканских культур, имеет тенденцию быть духовными церемониями. Она традиционно включает в себя большое разнообразие ударных и духовых инструментов, таких как барабаны, флейты, морские раковины (используемые в качестве труб) и «дождевые» трубки. Никаких остатков доколумбовых струнных инструментов не было найдено, пока археологи не обнаружили в Гватемале кувшин, приписываемый майя поздней классической эпохи (600–900 гг. н. э.); этот кувшин был украшен изображениями струнного музыкального инструмента, которые с тех пор были воспроизведены. Этот инструмент является одним из очень немногих струнных инструментов, известных в Америке до появления европейских музыкальных инструментов ; при игре он производит звук, имитирующий рычание ягуара. [193]

Изобразительное искусство коренных народов Америки составляет основную категорию в мировой коллекции произведений искусства . Вклады включают керамику , картины , ювелирные изделия , ткачество , скульптуры , плетение корзин , резьбу и бисероплетение . [194] Поскольку слишком много художников выдавали себя за коренных американцев и коренных жителей Аляски [195], чтобы извлечь выгоду из престижа искусства коренных народов в Соединенных Штатах, США приняли Закон об индейском искусстве и ремеслах 1990 года , требующий от художников доказать, что они были зачислены в штат или признанное на федеральном уровне племя . Чтобы поддержать продолжающуюся практику искусства и культуры американских индейцев , коренных жителей Аляски и коренных гавайцев в Соединенных Штатах, [196] Фонд Форда, защитники искусств и племена американских индейцев создали фонд пожертвований и учредили национальный Фонд искусств и культуры коренных народов в 2007 году. [197] [198]

После прихода испанцев процесс духовного завоевания был благоприятствован, среди прочего, литургической музыкальной службой, в которую были вовлечены туземцы, чьи музыкальные дары удивили миссионеров. Музыкальные дары туземцев были настолько велики, что они вскоре освоили правила контрапункта и полифонии и даже виртуозное обращение с инструментами. Это помогло гарантировать, что не было необходимости привозить больше музыкантов из Испании, что значительно раздражало духовенство. [199]

Решение, которое было предложено, состояло в том, чтобы не нанимать, а использовать определенное количество коренных жителей в музыкальной службе, не обучать их контрапункту, не позволять им играть на определенных инструментах ( например, духовые духовые в Оахаке , Мексика) и, наконец, не импортировать больше инструментов, чтобы коренные жители не имели к ним доступа. Последнее не было препятствием для музыкального наслаждения коренных жителей, которые имели опыт изготовления инструментов, в частности струнных ( скрипки и контрабасы ) или щипковых (терция). Именно там мы можем найти истоки того, что сейчас называется традиционной музыкой, инструменты которой имеют свою настройку и типичную западную структуру. [200]

В следующей таблице приведены оценки для каждой страны или территории в Америке популяций коренных народов и тех, кто имеет частично коренное происхождение, каждая из которых выражена в процентах от общей численности населения. Также приводится общий процент, полученный путем сложения обеих этих категорий.

Примечание: эти категории непоследовательно определяются и измеряются по-разному в разных странах. Некоторые цифры основаны на результатах генетических обследований населения, в то время как другие основаны на самоидентификации или наблюдательной оценке.

Коренные народы Канады (также известные как аборигены) [227] являются коренными народами в пределах границ Канады. Они включают в себя Первые нации [228] , инуитов [229] и метисов [230] , представляющих примерно 5,0% от общей численности населения Канады . Существует более 600 признанных правительств или групп Первых наций с отличительными культурами, языками, искусством и музыкой [231] [232]

Old Crow Flats и Bluefish Caves являются одними из самых ранних известных мест обитания человека в Канаде. Характеристики коренных культур в Канаде до европейской колонизации включали постоянные поселения, [233] сельское хозяйство, [234] гражданскую и церемониальную архитектуру, [235] сложные общественные иерархии и торговые сети . [236] Метисские народы смешанного происхождения возникли в середине 17 века, когда коренные народы и инуиты вступали в браки с европейцами, в первую очередь с французскими колонизаторами . [237] Коренные народы и метисы сыграли решающую роль в развитии европейских колоний в Канаде, особенно за их роль в оказании помощи европейцам во время североамериканской пушной торговли .

Различные законы , договоры и законодательство об аборигенах были приняты между европейскими иммигрантами и коренными группами по всей Канаде. Влияние поселенческого колониализма в Канаде можно увидеть в ее культуре, истории, политике, законах и законодательных органах. [238] Это привело к систематической отмене языков, традиций, религии коренных народов и деградации коренных общин, что было описано как геноцид коренных народов . [239]

Современное право коренных народов на самоуправление предусматривает самоуправление коренных народов в Канаде и управление их историческими, культурными, политическими, медицинскими и экономическими аспектами контроля в коренных общинах. Национальный день коренных народов признает обширные культуры и вклад коренных народов в историю Канады . [240] Первые нации, инуиты и метисы всех слоев общества стали видными деятелями и служили образцами для подражания в коренных общинах и помогали формировать канадскую культурную идентичность . [241].jpg/440px-Kulusuk,_Inuit_couple_(6822265499).jpg)

Гренландские инуиты ( калааллисут : kalaallit , тунумиисут : tunumiit , инуктун : inughuit ) являются коренной и самой многочисленной этнической группой в Гренландии . [242] Это означает, что в Дании есть одна официально признанная коренная группа . Инуиты — гренландские инуиты Гренландии и гренландский народ в Дании (инуиты, проживающие в Дании).

Примерно 89 процентов населения Гренландии, составляющего 57 695 человек, составляют гренландские инуиты , или 51 349 человек по состоянию на 2012 год [update]. [243] [244] Этнографически они состоят из трех основных групп:

На территории современной Мексики до прибытия испанских конкистадоров проживало множество коренных цивилизаций : ольмеки , процветавшие с 1200 г. до н. э. по 400 г. до н. э. в прибрежных районах Мексиканского залива ; сапотеки и миштеки , господствовавшие в горах Оахаки и на перешейке Теуантепек ; майя на Юкатане (и в соседних районах современной Центральной Америки ); пурепеча в современном Мичоакане и прилегающих районах, а также ацтеки / мексика , которые из своей центральной столицы в Теночтитлане доминировали над большей частью центра и юга страны (и неацтекским населением этих районов), когда Эрнан Кортес впервые высадился в Веракрусе .

В отличие от того, что было общим правилом в остальной части Северной Америки, история колонии Новая Испания была историей расового смешения ( mestizaje ). Метисы , которые в Мексике обозначают людей, которые не идентифицируют себя в культурном отношении ни с одной коренной группой, быстро стали составлять большинство населения колонии. Сегодня метисы в Мексике смешанного коренного и европейского происхождения (с небольшим африканским вкладом) по-прежнему составляют большинство населения. Генетические исследования расходятся во мнениях относительно того, преобладает ли коренное или европейское происхождение в популяции мексиканских метисов. [245] [246] В переписи INEGI 2020 года 23,2 миллиона человек (19,4% мексиканского населения в возрасте от 3 лет и старше) идентифицировали себя как коренные жители. [247] Несколько противоречиво, но в той же переписи 2020 года 11,8 миллионов человек (9,3% населения Мексики) были определены мексиканским правительством как коренные на основе языка, на котором говорят в их домохозяйствах. [248] Коренное население распределено по всей территории Мексики, но особенно сконцентрировано в Сьерра-Мадре-дель-Сур , на полуострове Юкатан и в самых отдаленных и труднодоступных районах, таких как Восточная Сьерра-Мадре , Западная Сьерра-Мадре и соседних районах. [249] CDI выделяет 62 группы коренных народов в Мексике, каждая из которых имеет уникальный язык. [250] [251]

В штатах Чьяпас и Оахака , а также во внутренних районах полуострова Юкатан , большая часть населения имеет коренное происхождение, при этом самой большой этнической группой являются майя с населением 900 000 человек. [252] Крупные коренные меньшинства, включая ацтеков или науа , пурепеча , масауа , отоми и миштеков, также присутствуют в центральных регионах Мексики. В северных регионах Мексики и регионах Бахио коренные жители составляют небольшое меньшинство.

Общий закон о языковых правах коренных народов предоставляет всем языкам коренных народов, на которых говорят в Мексике, независимо от числа носителей, такую же юридическую силу, как и испанскому языку на всех территориях, где на них говорят, и коренные народы имеют право запрашивать некоторые государственные услуги и документы на своих родных языках. [253] Наряду с испанским, закон предоставил им — более 60 языкам — статус «национальных языков». Закон включает все языки коренных народов Америки независимо от происхождения; то есть он включает языки коренных народов этнических групп, не являющихся коренными жителями данной территории. Национальная комиссия по развитию коренных народов признает язык кикапу , которые иммигрировали из Соединенных Штатов [254] , и признает языки беженцев-аборигенов из Гватемалы. [255] Мексиканское правительство поощряло и установило двуязычное начальное и среднее образование в некоторых сельских общинах коренных народов. Тем не менее, среди коренных народов Мексики 93% являются носителями испанского языка или двуязычными носителями испанского языка, и только около 62,4% из них (или 5,4% населения страны) говорят на языке коренных народов, а около шестой части не говорят по-испански (0,7% населения страны). [256]

Коренные народы Мексики имеют право на свободное определение в соответствии со второй статьей конституции. Согласно этой статье, коренным народам предоставляется: [257]

среди прочих прав.

Коренные народы на территории нынешних смежных Соединенных Штатов , включая их потомков, обычно назывались американскими индейцами или просто индейцами внутри страны, а с конца 20-го века термин «коренные американцы» стал общепринятым . На Аляске коренные народы принадлежат к 11 культурам с 11 языками. К ним относятся юпик острова Святого Лаврентия , инупиаты , атабаски , юпик , купик , унангакс , алутиик , эяк , хайда , цимшиан и тлингит , [258] и все вместе называются коренными жителями Аляски . К ним относятся коренные народы Америки, а также инуиты, которые являются отдельными, но занимают районы региона.

Соединенные Штаты имеют власть над коренными полинезийцами , которые включают гавайцев , маршалльцев (микронезийцев) и самоанцев ; политически они классифицируются как тихоокеанские островитяне . Они географически, генетически и культурно отличаются от коренных народов материковых континентов Америки.

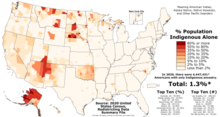

В переписи 2020 года 2,9% населения США заявили, что имеют некоторую степень индейского наследия. При ответе на вопрос о расовом происхождении 3,7 миллиона человек идентифицировали себя исключительно как «американские индейцы или коренные жители Аляски», в то время как еще 5,9 миллиона сделали это в сочетании с другими расами. [259] Ацтеки были крупнейшей отдельной группой коренных американцев в переписи 2020 года, в то время как чероки были крупнейшей группой в сочетании с любой другой расой. [260] Племена установили свои критерии членства, которые часто основаны на количестве крови , прямом происхождении или месте жительства. Меньшинство коренных американцев живет в земельных единицах, называемых индейскими резервациями .

Некоторые племена Калифорнии и Юго-Запада, такие как Кумеяай , Кокопа , Паскуа-Яки , Тохоно О'одхам и Апачи , охватывают обе стороны границы США и Мексики. По договору люди Хауденосауни имеют законное право свободно пересекать границу США и Канады. Атабаски , Тлингиты , Хайда , Цимшиан , Инупиаты , Блэкфит , Накота , Кри , Анишинабе , Гуроны , Ленапе , Микмак , Пенобскоты и Хауденосауни, среди прочих, живут как в Канаде, так и в Соединенных Штатах, чья международная граница проходит через их общую культурную территорию.

Метисы (смешанные европейцы и коренные народы) составляют около 34% населения; несмешанные майя составляют еще 10,6% ( кекчи , мопаны и юкатеки ). Гарифуна , прибывшие в Белиз в 19 веке из Сент-Винсента и Гренадин , имеют смешанное африканское , карибское и аравакское происхождение и составляют еще 6% населения. [261]

Насчитывается более 114 000 жителей с индейским происхождением, что составляет 2,4% населения. Большинство из них живут в уединенных резервациях, распределенных между восемью этническими группами: Китирриси (в Центральной долине), Матамбу или Чоротега (Гуанакасте), Малеку (Северная Алахуэла), Брибри (Южная Атлантика), Кабекар (Кордильера-де-Таламанка), Борука (Южная Коста-Рика) и Нгабе (Южная Коста-Рика вдоль границы с Панамой).

Для этих коренных народов характерны изделия из дерева, такие как маски, барабаны и другие художественные фигуры, а также ткани из хлопка.

Их существование основано на сельском хозяйстве, основными культурами которого являются кукуруза, бобы и бананы. [ необходима цитата ]

Оценки численности коренного населения Сальвадора различаются. В последний раз перепись населения включала вариант «коренное население» в 2007 году, когда было подсчитано, что 0,23% населения идентифицировали себя как коренное население. [27] Исторически оценки заявляли более высокие цифры. Перепись 1930 года показала, что 5,6% были коренными. [262] К середине 20-го века могло быть до 20% (или 400 000), которые могли бы считаться «коренными». Другая оценка показала, что к концу 1980-х годов 10% населения были коренными, а еще 89% были метисами (или людьми смешанного европейского и коренного происхождения). [263]

Большая часть Сальвадора была домом для пипилов , ленка , шинка и какавира . Пипилы жили в западном Сальвадоре , говорили на языке нават и имели там много поселений, наиболее заметным из которых был Кускатлан . У пипилов не было драгоценных минеральных ресурсов, но у них была богатая и плодородная земля , пригодная для земледелия. Испанцы были разочарованы, не найдя золота или драгоценностей в Сальвадоре, как в других странах, таких как Гватемала или Мексика, но, узнав о плодородных землях Сальвадора, они попытались завоевать его. Известными воинами мезоамериканских коренных народов, поднявшими военное восстание против испанцев, были принцы Атональ и Атлакатль из народа пипил в центральном Сальвадоре и принцесса Анту Силан Улап из народа ленка в восточном Сальвадоре, которые видели в испанцах не богов, а варварских захватчиков. После ожесточенных сражений пипил успешно отбили испанскую армию во главе с Педро де Альварадо вместе со своими союзниками-индейцами (тлашкалами), отправив их обратно в Гватемалу. После многих других атак с армией, усиленной союзниками-индейцами, испанцы смогли завоевать Кускатлан. После дальнейших атак испанцы также завоевали народ ленка. В конце концов, испанцы вступили в браки с женщинами пипил и ленка, в результате чего появилось метисское население, которое составило подавляющее большинство сальвадорского народа. Сегодня многие пипил и другие коренные народы живут во многих небольших городах Сальвадора, таких как Исалько , Панчималько , Сакакойо и Науисалько .

.jpg/440px-Image_of_photo_of_Mayan_woman_(6849889936).jpg)

В Гватемале проживает одно из крупнейших коренных народов в Центральной Америке , примерно 43,6% населения считают себя коренными. [264] Коренная демографическая часть населения Гватемалы состоит из большинства групп майя и одной немайяской группы. Часть, говорящая на языке майя, составляет 29,7% населения и разделена на 23 группы, а именно: кекчи 8,3%, киче 7,8%, мам 4,4%, какчикель 3%, кванджобаль 1,2%, покомчи 1% и другие 4%. [264] Немайянская группа состоит из шинка , которые являются еще одной группой коренных народов, составляющих 1,8% населения. [264] Другие источники указывают, что от 50% до 60% населения могут быть коренными, поскольку часть населения метисов преимущественно являются коренными.

Племена майя охватывают обширную географическую область по всей Центральной Америке и простираются за пределы Гватемалы в другие страны. Можно найти большие группы народа майя в Бока-Коста, в южных частях Гватемалы, а также в Западном нагорье, живущих вместе в тесных общинах. [265] Внутри этих общин и за их пределами около 23 языков коренных народов (или языков коренных американцев ) используются в качестве первого языка. Из этих 23 языков они получили официальное признание правительства только в 2003 году в соответствии с Законом о национальных языках. [264] Закон о национальных языках признает 23 языка коренных народов, включая язык шинка, обязывая государственные и правительственные учреждения не только переводить, но и предоставлять услуги на этих языках. [266] Он будет предоставлять услуги на языках какчикель , гарифуна , кекчи , мам , киче и шинка . [267]

Закон о национальных языках был попыткой предоставить и защитить права коренных народов, которые им ранее не предоставлялись. Наряду с Законом о национальных языках, принятым в 2003 году, в 1996 году Конституционный суд Гватемалы ратифицировал Конвенцию МОТ № 169 о коренных и племенных народах. [268] Конвенция МОТ № 169 о коренных и племенных народах также известна как Конвенция № 169. Это единственный международный закон в отношении коренных народов, который могут принять независимые страны. Конвенция устанавливает, что правительства, такие как Гватемала, должны консультироваться с коренными группами, прежде чем какие-либо проекты будут осуществляться на племенных землях. [269]

About 5 percent of the population is of full-blooded Indigenous descent, but as much as 80 percent of Hondurans are mestizo or part-Indigenous with European admixture, and about 10 percent are of Indigenous or African descent.[270] The largest concentrations of Indigenous communities in Honduras are in the westernmost areas facing Guatemala and along the coast of the Caribbean Sea, as well as on the border with Nicaragua.[270] The majority of Indigenous people are Lencas, Miskitos to the east, Mayans, Pech, Sumos, and Tolupan.[270]

About 5 percent of the Nicaraguan population is Indigenous. The largest Indigenous group in Nicaragua is the Miskito people. Their territory extended from Cabo Camarón, Honduras, to La Cruz de Rio Grande, Nicaragua along the Mosquito Coast. There is a native Miskito language, but large numbers speak Miskito Coast Creole, Spanish, Rama, and other languages. Their use of Creole English came about through frequent contact with the British, who colonized the area. Many Miskitos are Christians. Traditional Miskito society was highly structured, politically and otherwise. It had a king, but he did not have total power. Instead, the power was split between himself, a Miskito Governor, a Miskito General, and by the 1750s, a Miskito Admiral. Historical information on Miskito kings is often obscured by the fact that many of the kings were semi-mythical.

Another major Indigenous culture in eastern Nicaragua is the Mayangna (or Sumu) people, counting some 10,000 people.[271] A smaller Indigenous culture in southeastern Nicaragua is the Rama.

Other Indigenous groups in Nicaragua are located in the central, northern, and Pacific areas and they are self-identified as follows: Chorotega, Cacaopera (or Matagalpa), Xiu-Subtiaba, and Nicarao.[272]

Indigenous peoples of Panama, or Native Panamanians, are the native peoples of Panama. According to the 2010 census, they make up 12.3% of the overall population of 3.4 million, or just over 418,000 people. The Ngäbe and Buglé comprise half of the indigenous peoples of Panama.[273]

Many of the Indigenous Peoples live on comarca indígenas,[274] which are administrative regions for areas with substantial Indigenous populations. Three comarcas (Comarca Emberá-Wounaan, Guna Yala, Ngäbe-Buglé) exist as equivalent to a province, with two smaller comarcas (Guna de Madugandí and Guna de Wargandí) subordinate to a province and considered equivalent to a corregimiento (municipality).

In 2005, the Indigenous population living in Argentina (known as pueblos originarios) numbered about 600,329 (1.6% of the total population); this figure includes 457,363 people who self-identified as belonging to an Indigenous ethnic group and 142,966 who identified themselves as first-generation descendants of an Indigenous people.[275] The ten most populous Indigenous peoples are the Mapuche (113,680 people), the Kolla (70,505), the Toba (69,452), the Guaraní (68,454), the Wichi (40,036), the Diaguita–Calchaquí (31,753), the Mocoví (15,837), the Huarpe (14,633), the Comechingón (10,863) and the Tehuelche (10,590). Minor but important peoples are the Quechua (6,739), the Charrúa (4,511), the Pilagá (4,465), the Chané (4,376), and the Chorote (2,613). The Selk'nam (Ona) people are now virtually extinct in its pure form. The languages of the Diaguita, Tehuelche, and Selk'nam nations have become extinct or virtually extinct: the Cacán language (spoken by Diaguitas) in the 18th century and the Selk'nam language in the 20th century; one Tehuelche language (Southern Tehuelche) is still spoken by a handful of elderly people.

In Bolivia, the 2012 National Census reported that 41% of residents over the age of 15 are of Indigenous origin. Some 3.7% report growing up with an Indigenous mother tongue but do not identify as Indigenous.[276] When both of these categories are totaled, and children under 15, some 66.4% of Bolivia's population was recorded as Indigenous in the 2001 Census.[277]

The 2021 National Census, recognizes 38 cultures, each with its language, as part of a pluri-national state. Some groups, including CONAMAQ (the National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu), draw ethnic boundaries within the Quechua- and Aymara-speaking population, resulting in a total of 50 Indigenous peoples native to Bolivia.

The largest Indigenous ethnic groups are Quechua, about 2.5 million people; Aymara, 2 million; Chiquitano, 181,000; Guaraní, 126,000; and Mojeño, 69,000. Some 124,000 belong to smaller Indigenous groups.[278] The Constitution of Bolivia, enacted in 2009, recognizes 36 cultures, each with its language, as part of a pluri-national state. Some groups, including CONAMAQ (the National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu), draw ethnic boundaries within the Quechua- and Aymara-speaking population, resulting in a total of 50 Indigenous peoples native to Bolivia.

Large numbers of Bolivian highland peasants retained Indigenous language, culture, customs, and communal organization throughout the Spanish conquest and the post-independence period. They mobilized to resist various attempts at the dissolution of communal landholdings and used legal recognition of "empowered caciques" to further communal organization. Indigenous revolts took place frequently until 1953.[279] While the National Revolutionary Movement government began in 1952 and discouraged people identifying as Indigenous (reclassifying rural people as campesinos, or peasants), renewed ethnic and class militancy re-emerged in the Katarista movement beginning in the 1970s.[280] Many lowland Indigenous peoples, mostly in the east, entered national politics through the 1990 March for Territory and Dignity organized by the CIDOB confederation. That march successfully pressured the national government to sign the ILO Convention 169 and to begin the still-ongoing process of recognizing and giving official titles to Indigenous territories. The 1994 Law of Popular Participation granted "grassroots territorial organizations;" these are recognized by the state and have certain rights to govern local areas.

Some radio and television programs are produced in the Quechua and Aymara languages. The constitutional reform in 1997 recognized Bolivia as a multi-lingual, pluri-ethnic society and introduced education reform. In 2005, for the first time in the country's history, an Indigenous Aymara, Evo Morales, was elected as president.

Morales began work on his "Indigenous autonomy" policy, which he launched in the eastern lowlands department on 3 August 2009. Bolivia was the first nation in the history of South America to affirm the right of Indigenous people to self-government.[281] Speaking in Santa Cruz Department, the President called it "a historic day for the peasant and Indigenous movement", saying that, though he might make errors, he would "never betray the fight started by our ancestors and the fight of the Bolivian people".[281] A vote on further autonomy for jurisdictions took place in December 2009, at the same time as general elections to office. The issue divided the country.[282]

At that time, Indigenous peoples voted overwhelmingly for more autonomy: five departments that had not already done so voted for it;[283][284] as did Gran Chaco Province in Taríja, for regional autonomy;[285] and 11 of 12 municipalities that had referendums on this issue.[283]

Indigenous peoples of Brazil make up 0.4% of Brazil's population, or about 817,000 people, but millions of Brazilians are mestizo or have some Indigenous ancestry.[286] Indigenous peoples are found in the entire territory of Brazil, although in the 21st century, the majority of them live in Indigenous territories in the North and Center-Western parts of the country. On 18 January 2007, Fundação Nacional do Índio (FUNAI) reported that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. Brazil is now the nation that has the largest number of uncontacted tribes, and the island of New Guinea is second.[286]

The Washington Post reported in 2007, "As has been proved in the past when uncontacted tribes are introduced to other populations and the microbes they carry, maladies as simple as the common cold can be deadly. In the 1970s, 185 members of the Panara tribe died within two years of discovery after contracting such diseases as flu and chickenpox, leaving only 69 survivors."[287]

According to the 2012 Census, 10% of the Chilean population, including the Rapa Nui (a Polynesian people) of Easter Island, was Indigenous, although most show varying degrees of mixed heritage.[288] Many are descendants of the Mapuche and live in Santiago, Araucanía, and Los Lagos Region. The Mapuche successfully fought off defeat in the first 300–350 years of Spanish rule during the Arauco War. Relations with the new Chilean Republic were good until the Chilean state decided to occupy their lands. During the Occupation of Araucanía, the Mapuche surrendered to the country's army in the 1880s. Their land was opened to settlement by Chileans and Europeans. Conflict over Mapuche land rights continues to the present.

Other groups include the Aymara, the majority of whom live in Bolivia and Peru, with smaller numbers in the Arica-Parinacota and Tarapacá regions, and the Atacama people (Atacameños), who reside mainly in El Loa.

A minority today within Colombia's mostly Mestizo and White Colombian population, Indigenous peoples living in Colombia, consist of around 85 distinct cultures and around 1,905,617 people, however, it is likely much higher.[289][290] A variety of collective rights for Indigenous peoples are recognized in the 1991 Constitution. One of the influences is the Muisca culture, a subset of the larger Chibcha ethnic group, famous for their use of gold, which led to the legend of El Dorado. At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Muisca were the largest Indigenous civilization geographically between the Inca and the Aztec empires.

Ecuador was the site of many Indigenous cultures, and civilizations of different proportions. An early sedentary culture, known as the Valdivia culture, developed in the coastal region, while the Caras and the Quitus unified to form an elaborate civilization that ended at the birth of the Capital Quito. The Cañaris near Cuenca were the most advanced, and most feared by the Inca, due to their fierce resistance to the Incan expansion. Their architectural remains were later destroyed by the Spaniards and the Incas.

Between 55% and 65% of Ecuador's population consists of Mestizos of mixed indigenous and European ancestry while indigenous people comprise about 25%.[291] Genetic analysis indicates that Ecuadorian Mestizos are of predominantly indigenous ancestry.[292] Approximately 96.4% of Ecuador's Indigenous population are Highland Quichuas living in the valleys of the Sierra region. Primarily consisting of the descendants of peoples conquered by the Incas, they are Kichwa speakers and include the Caranqui, the Otavalos, the Cayambe, the Quitu-Caras, the Panzaleo, the Chimbuelo, the Salasacan, the Tugua, the Puruhá, the Cañari, and the Saraguro. Linguistic evidence suggests that the Salascan and the Saraguro may have been the descendants of Bolivian ethnic groups transplanted to Ecuador as mitimaes.

Coastal groups, including the Awá, Chachi, and the Tsáchila, make up 0.24% percent of the Indigenous population, while the remaining 3.35 percent live in the Oriente and consist of the Oriente Kichwa (the Canelo and the Quijos), the Shuar, the Huaorani, the Siona-Secoya, the Cofán, and the Achuar.

In 1986, Indigenous peoples formed the first "truly" national political organization. The Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) has been the primary political institution of Indigenous peoples since then and is now the second-largest political party in the nation. It has been influential in national politics, contributing to the ouster of presidents Abdalá Bucaram in 1997 and Jamil Mahuad in 2000.

French Guiana is home to approximately 10,000 indigenous peoples, such as the Kalina and Lokono. Over time, the indigenous population has protested against various environmental issues, such as illegal gold mining, pollution, and a drastic decrease in wild game.

During the early stages of colonization, the indigenous peoples in Guyana partook in trade relations with Dutch settlers and assisted in militia services such as hunting down escaped slaves for the British, which continued until the 19th century. Indigenous Guyanese people are responsible for the invention of the canoe as well as Guyanese pepperpot and the foundation of the Alleluia church.

Guyana's indigenous peoples have been recognized under the Constitution of 1965 and comprise 9.16% of the overall population.

The vast majority of indigenous peoples in Paraguay are concentrated in the Gran Chaco region in the northwest of the country, with the Guaraní making up the majority of the indigenous population in Paraguay. The Guaraní language is recognized as an official language alongside Spanish, with approximately 90% of the population speaking Guaraní. The indigenous population in Paraguay suffers from several social issues such as low literacy rates and inaccessibility to safe drinking water and electricity.

According to the 2017 Census, the Indigenous population in Peru makes up approximately 26%.[5] However, this does not include Mestizos of mixed indigenous and European descent, who make up the majority of the population. Genetic testing indicates that Peruvian Mestizos are of predominantly indigenous ancestry.[293] Indigenous traditions and customs have shaped the way Peruvians live and see themselves today. Cultural citizenship—or what Renato Rosaldo has called, "the right to be different and to belong, in a democratic, participatory sense" (1996:243)—is not yet very well developed in Peru. This is perhaps no more apparent than in the country's Amazonian regions where Indigenous societies continue to struggle against state-sponsored economic abuses, cultural discrimination, and pervasive violence.[294]

According to the 2012 census, the indigenous population of Suriname numbers around 20,000, amounting to 3.8% of the population. The most numerous indigenous groups in Suriname primarily comprise the Lokono, Kalina, Tiriyó, and Wayana.

Unlike most other Spanish-speaking countries, indigenous peoples are not a significant element in Uruguay, as the entire indigenous population is virtually extinct, with a few exceptions such as the Guaraní. Approximately 2.4% of the population in Uruguay is reported to have indigenous ancestry.[224]

Most Venezuelans have some degree of indigenous heritage even if they may not identify as such. The 2011 census estimated that around 52% of the population identified as mestizo. But those who identify as Indigenous, from being raised in those cultures, make up only around 2% of the total population. The Indigenous peoples speak around 29 different languages and many more dialects. As some of the ethnic groups are very small, their native languages are in danger of becoming extinct in the next decades. The most important Indigenous groups are the Ye'kuana, the Wayuu, the Kali'na, the Ya̧nomamö, the Pemon, and the Warao. The most advanced Indigenous peoples to have lived within the boundaries of present-day Venezuela are thought to have been the Timoto-cuicas, who lived in the Venezuelan Andes. Historians estimate that there were between 350 thousand and 500 thousand Indigenous inhabitants at the time of Spanish colonization. The most densely populated area was the Andean region (Timoto-cuicas), thanks to their advanced agricultural techniques and ability to produce a surplus of food.

The 1999 constitution of Venezuela gives indigenous peoples special rights, although the vast majority of them still live in very critical conditions of poverty. The government provides primary education in their languages in public schools to some of the largest groups, in efforts to continue the languages.

The indigenous population of the Caribbean islands consisted of the Taíno of the Lucayan Archipelago, the Greater Antilles and the northern Lesser Antilles, the Kalinago of the Lesser Antilles, the Ciguayo and Macorix of parts of Hispaniola, and the Guanahatabey of western Cuba. The overall population suffered the most adverse colonial effects out of all the indigenous populations in the Americas, as the Kalinago have been reduced to a few islands in the Lesser Antilles such as Dominica and the Taíno are culturally extinct, though a large proportion of populations in Greater Antillean islands such as Puerto Rico and Cuba to a lesser extent,[295] possesses degrees of Taíno ancestry. The Cayman Islands were the only island group in the Caribbean to have remained unsettled by indigenous peoples before the colonial era.[296]

Historically, during the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, the territory was ruled as a province of the Mexico-centered Viceroyalty of New Spain and thus many Mexicans including those of indgenous Aztec and Tlaxcalan descent were sent as colonists there.[297]: Chpt. 6 According to a genetic study by the National Geographic around 2% of the Philippine population are Native American in descent.[298][299]

Since the late 20th century, Indigenous peoples in the Americas have become more politically active in asserting their treaty rights and expanding their influence. Some have organized to achieve some sort of self-determination and preservation of their cultures. Organizations such as the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin and the Indian Council of South America are examples of movements that are overcoming national borders to reunite Indigenous populations, for instance, those across the Amazon Basin. Similar movements for Indigenous rights can also be seen in Canada and the United States, with movements like the International Indian Treaty Council and the accession of native Indigenous groups into the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization.

There has been a recognition of Indigenous movements on an international scale. The membership of the United Nations voted to adopt the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, despite dissent from some of the stronger countries of the Americas.

In Colombia, various Indigenous groups have protested the denial of their rights. People organized a march in Cali in October 2008 to demand the government live up to promises to protect Indigenous lands, defend the Indigenous against violence, and reconsider the free trade pact with the United States.[300]

_(cropped).jpg/440px-Presidentes_del_Perú_y_Bolivia_inauguran_Encuentro_Presidencial_y_III_Gabinete_Binacional_Perú-Bolivia_(36962597345)_(cropped).jpg)

The first Indigenous President of the Americas was José María Melo, of Pijao descent, and led Colombia in 1854 starting on April 17, 1854. José was born on October 9, 1800, in Chaparral, Tolima, and before his presidency, he fought alongside Simon Bolivar in the Spanish-American Wars of Independence. José María Melo led the Republic of New Granada during the Colombian Civil War of 1854 but eventually lost and was exiled on December 4, 1854.[301]

The first Indigenous candidate to be democratically elected as head of a country in the Americas was Benito Juárez, a Zapotec Mexican who was elected President of Mexico in 1858 and led the country until 1872 and led the country to victory during the Second French intervention in Mexico.[302]

In 1930 Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro became the first Peruvian President with Indigenous Peruvian ancestry and the first in South America.[303] He came to power in a military coup.

In 2005, Evo Morales of the Aymara people was the first Indigenous candidate elected as president of Bolivia and the first elected in South America.[304]

Genetic history of Indigenous peoples of the Americas primarily focuses on Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups and Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups. "Y-DNA" is passed solely along the patrilineal line, from father to son, while "mtDNA" is passed down the matrilineal line, from mother to offspring of both sexes. Neither recombines and thus Y-DNA and mtDNA change only by chance mutation at each generation with no intermixture between parents' genetic material.[307] Autosomal "atDNA" markers are also used but differ from mtDNA or Y-DNA in that they overlap significantly.[308] AtDNA is generally used to measure the average continent-of-ancestry genetic admixture in the entire human genome and related isolated populations.[308]

Genetic comparisons of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and Y-chromosome of Native Americans to that of certain Siberian and Central Asian peoples (specifically Paleo-Siberians, Turkic, and historically the Okunev culture) have led Russian researcher I.A. Zakharov to believe that, among all the previously studied Asian peoples, it is "the peoples living between Altai and Lake Baikal along the Sayan mountains that are genetically closest to" Indigenous Americans.[309]

Some scientific evidence links them to North Asian peoples, specifically the Indigenous peoples of Siberia, such as the Ket, Selkup, Chukchi, and Koryak peoples. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to some extent to North Asian populations by the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, and limited DNA studies.[310][311][312]