Испания , [f] официально Королевство Испания , [a] [g] — страна на юго-западе Европы с территориями в Северной Африке . [11] [h] Это самая большая страна в Южной Европе и четвёртое по численности населения государство-член Европейского Союза . Охватывая большую часть Пиренейского полуострова , её территория также включает Канарские острова в Атлантическом океане , Балеарские острова в Средиземном море и автономные города Сеута и Мелилья в Африке. Полуостровная Испания граничит на севере с Францией , Андоррой и Бискайским заливом ; на востоке и юге со Средиземным морем и Гибралтаром ; и на западе с Португалией и Атлантическим океаном. Столица и крупнейший город Испании — Мадрид , а другие крупные городские районы включают Барселону , Валенсию и Сарагосу .

В ранней античности Пиренейский полуостров населяли кельты , иберы и другие доримские народы . С завоеванием Пиренейского полуострова римлянами была основана провинция Испания . После романизации и христианизации Испании падение Западной Римской империи положило начало внутренней миграции племен из Центральной Европы, включая вестготов , которые образовали Вестготское королевство с центром в Толедо . В начале восьмого века большая часть полуострова была захвачена Омейядским халифатом , и во время раннего исламского правления Аль-Андалус стал доминирующей полуостровной державой с центром в Кордове . Несколько христианских королевств возникли в Северной Иберии, главными из которых были Астурия , Леон , Кастилия , Арагон , Наварра и Португалия ; предпринял периодическую военную экспансию на юг и переселение, известную как Реконкиста , с целью свержения исламского правления в Иберии, что завершилось захватом христианами королевства Насридов в Гранаде в 1492 году. Династический союз Кастилии и Арагона в 1479 году под руководством католических монархов часто рассматривается как фактическое объединение Испании как национального государства .

В эпоху Великих географических открытий Испания была пионером в исследовании Нового Света , совершила первое кругосветное плавание и сформировала одну из крупнейших империй в истории . [12] Испанская империя достигла мирового масштаба и распространилась на все континенты, поддерживая рост глобальной торговой системы, подпитываемой в первую очередь драгоценными металлами . В 18 веке реформы Бурбонов централизовали материковую Испанию. [13] В 19 веке, после наполеоновской оккупации и победоносной испанской войны за независимость , следующие политические разногласия между либералами и абсолютистами привели к отделению большинства американских колоний . Эти политические разногласия окончательно сошлись в 20 веке с гражданской войной в Испании , что привело к франкистской диктатуре , которая просуществовала до 1975 года. С восстановлением демократии и вступлением в Европейский союз страна пережила экономический бум , который глубоко преобразил ее в социальном и политическом плане. Начиная с Сигло де Оро , испанское искусство , архитектура , музыка , поэзия , живопись , литература и кухня оказали влияние во всем мире, особенно в Западной Европе и Америке . Как отражение своего большого культурного богатства , Испания является второй по посещаемости страной в мире , имеет одно из самых больших в мире по количеству объектов всемирного наследия , и является самым популярным местом для европейских студентов. [14] Ее культурное влияние распространяется на более чем 600 миллионов испаноговорящих , что делает испанский вторым по распространенности родным языком в мире и самым распространенным в мире романским языком . [15]

Испания является светской парламентской демократией и конституционной монархией [16] с королем Филиппом VI в качестве главы государства . Развитая страна , крупная передовая капиталистическая экономика [17] с пятнадцатой по величине экономикой в мире по номинальному ВВП и пятнадцатой по величине по ППС . Испания является членом Организации Объединенных Наций , Европейского союза, еврозоны , Организации Североатлантического договора (НАТО), постоянным гостем G20 и входит во многие другие международные организации, такие как Совет Европы (СЕ), Организация иберо-американских государств (ОЕИ), Союз Средиземноморья , Организация экономического сотрудничества и развития (ОЭСР), Организация по безопасности и сотрудничеству в Европе (ОБСЕ) и Всемирная торговая организация (ВТО).

Название Испания ( España ) происходит от Hispania , названия, которое римляне использовали для Пиренейского полуострова и его провинций во времена Римской империи . Этимологическое происхождение термина Hispania неясно, хотя финикийцы называли этот регион Spania (что означает «Земля кроликов »), поэтому наиболее принятой теорией является финикийская . [18] Существует ряд сообщений и гипотез о его происхождении:

Хесус Луис Кунчиллос утверждал, что корень термина span — финикийское слово spy , означающее « ковать металлы ». Следовательно, i-spn-ya будет означать «земля, где куются металлы». [19] Это может быть производным от финикийского I-Shpania , означающего «остров кроликов», «земля кроликов» или «край», что является отсылкой к расположению Испании в конце Средиземного моря; римские монеты, отчеканенные в этом регионе во времена правления Адриана, показывают женскую фигуру с кроликом у ее ног, [20] а Страбон называл его «землей кроликов». [21] Рассматриваемое слово на самом деле означает « Hyrax », возможно, из-за того, что финикийцы путали этих двух животных. [22]

Существует также утверждение, что «Испания» происходит от баскского слова Ezpanna , означающего «край» или «граница», что является еще одной ссылкой на тот факт, что Пиренейский полуостров представляет собой юго-западный угол европейского континента. [23]

Археологические исследования в Атапуэрке показывают, что Пиренейский полуостров был заселен гоминидами 1,3 миллиона лет назад. [24]

Современные люди впервые прибыли в Иберию с севера пешком около 35 000 лет назад. [25] [ неудачная проверка ] Самыми известными артефактами этих доисторических человеческих поселений являются рисунки в пещере Альтамира в Кантабрии на севере Иберии, которые были созданы в период с 35 600 по 13 500 гг. до н. э. кроманьонцами . [26] [27] Археологические и генетические данные свидетельствуют о том, что Пиренейский полуостров служил одним из нескольких крупных убежищ , из которых северная Европа была повторно заселена после окончания последнего ледникового периода .

Две крупнейшие группы, населявшие Пиренейский полуостров до римского завоевания, были иберы и кельты . Иберы населяли средиземноморскую сторону полуострова. Кельты населяли большую часть внутренних и атлантических сторон полуострова. Баски занимали западную часть Пиренейского хребта и прилегающие районы; финикийские тартессы процветали на юго-западе; а лузитаны и веттоны занимали районы на центральном западе. Несколько городов были основаны финикийцами вдоль побережья , а торговые форпосты и колонии были созданы греками на востоке. В конце концов, финикийцы - карфагеняне расширили свои владения вглубь страны в сторону Месеты; однако из-за воинственных внутренних племен карфагеняне поселились на побережьях Пиренейского полуострова.

Во время Второй Пунической войны , примерно между 210 и 205 годами до н. э., расширяющаяся Римская республика захватила карфагенские торговые колонии вдоль побережья Средиземного моря. Хотя римлянам потребовалось почти два столетия, чтобы завершить завоевание Пиренейского полуострова , они сохраняли контроль над ним более шести столетий. Римское правление было связано законом, языком и римской дорогой . [28]

Культуры доримского населения постепенно романизировались (латинизировались) с разной скоростью в зависимости от того, в какой части полуострова они жили, а местные лидеры были приняты в римский аристократический класс. [i] [29]

Hispania служила зернохранилищем для римского рынка, а ее гавани экспортировали золото, шерсть , оливковое масло и вино. Сельскохозяйственное производство увеличилось с введением ирригационных проектов, некоторые из которых до сих пор используются. Императоры Адриан , Траян , Феодосий I и философ Сенека родились в Hispania. [j] Христианство было введено в Hispania в I веке н. э. и стало популярным в городах во II веке. [29] Большинство современных языков и религий Испании, а также основа ее законов берут свое начало в этом периоде. [28] Начиная с 170 года н. э., имели место вторжения североафриканских мавров в провинцию Бетика . [30]

.jpg/440px-Coronas_votivas_visigodas_en_el_MAN_(16846328238).jpg)

Германские свебы и вандалы , вместе с сарматскими аланами , вошли на полуостров после 409 года, ослабив юрисдикцию Западной Римской империи над Испанией. Свебы основали королевство на северо-западе Иберии, тогда как вандалы обосновались на юге полуострова к 420 году, прежде чем переправиться в Северную Африку в 429 году. По мере распада западной империи социальная и экономическая база значительно упростилась; последующие режимы сохранили многие институты и законы поздней империи, включая христианство и ассимиляцию в развивающуюся римскую культуру.

Византийцы основали западную провинцию, Спанию , на юге, с намерением возродить римское правление по всей Иберии. Однако в конечном итоге Испания была воссоединена под вестготским правлением .

.jpg/440px-Entrada_de_Roger_de_Flor_en_Constantinopla_(Palacio_del_Senado_de_España).jpg)

С 711 по 718 год, в рамках экспансии Омейядского халифата , который завоевал Северную Африку у Византийской империи , почти весь Пиренейский полуостров был завоеван мусульманами через Гибралтарский пролив, что привело к краху Вестготского королевства. Только небольшая область на горном севере полуострова выделялась из территории, захваченной во время первоначального вторжения. Королевство Астурия-Леон консолидировалось на этой территории. Другие христианские королевства, такие как Наварра и Арагон на горном севере, в конечном итоге нахлынули на консолидацию графств Каролингской марки Hispanica . [31] В течение нескольких столетий колеблющаяся граница между мусульманскими и христианскими контролируемыми территориями полуострова проходила вдоль долин Эбро и Дору .

Переход в ислам происходил все более быстрыми темпами. Считается, что к концу X века большинство населения Аль-Андалуса составляли мулади (мусульмане этнического иберийского происхождения). [32] [33]

В IX и X веках викинги совершили ряд набегов на побережье Пиренейского полуострова. [34] Первый зарегистрированный набег викингов на Иберию состоялся в 844 году; он закончился неудачей, многие викинги были убиты баллистами галисийцев ; семьдесят ладей викингов были захвачены на берегу и сожжены войсками короля Рамиро I Астурийского .

В XI веке Кордовский халифат распался, распавшись на ряд мелких королевств ( Taifas ), [35] часто подлежащих выплате формы денег за защиту ( Parias ) северным христианским королевствам, которые в противном случае предприняли южную территориальную экспансию. Захват стратегического города Толедо в 1085 году ознаменовал собой значительный сдвиг в балансе сил в пользу христианских королевств. [ необходима цитата ] Прибытие из Северной Африки исламских правящих сект Альморавидов и Альмохадов достигло временного единства на территории, управляемой мусульманами, с более строгим, менее терпимым применением ислама и частично отменило некоторые христианские территориальные завоевания.

Королевство Леон было сильнейшим христианским королевством на протяжении столетий. В 1188 году в Леоне состоялась первая форма (ограниченная епископами, магнатами и «избранными гражданами каждого города») современной парламентской сессии в Европе ( Кортесы Леона ). [36] Королевство Кастилия , образованное на территории Леона, стало его преемником как сильнейшее королевство. Короли и знать боролись за власть и влияние в этот период. Пример римских императоров повлиял на политические цели Короны, в то время как знать извлекла выгоду из феодализма .

Мусульманские крепости в долине Гвадалквивира, такие как Кордова (1236) и Севилья (1248), пали под натиском Кастилии в XIII веке. Графство Барселона и Королевство Арагон вступили в династический союз и приобрели территорию и власть в Средиземноморье. В 1229 году была завоевана Майорка , а в 1238 году — Валенсия. В XIII и XIV веках североафриканские Мариниды основали несколько анклавов вокруг Гибралтарского пролива. После окончания Гранадской войны султанат Насридов Гранады (оставшееся мусульманское государство на Пиренейском полуострове после 1246 года) капитулировал в 1492 году перед военной силой католических монархов и с тех пор был включен в состав Кастилийской короны. [37]

В 1469 году короны христианских королевств Кастилии и Арагона были объединены браком их монархов, Изабеллы I и Фердинанда II, соответственно. В 1492 году евреи были вынуждены выбирать между обращением в католичество или изгнанием; [38] около 200 000 евреев были изгнаны из Кастилии и Арагона . 1492 год также ознаменовался прибытием Христофора Колумба в Новый Свет во время путешествия, финансируемого Изабеллой. Первое путешествие Колумба пересекло Атлантику и достигло Карибских островов, положив начало европейскому исследованию и завоеванию Америки. Гранадский договор гарантировал религиозную терпимость по отношению к мусульманам, [39] в течение нескольких лет, прежде чем ислам был объявлен вне закона в 1502 году в Кастилии и в 1527 году в Арагоне, что привело к тому, что оставшееся мусульманское население стало номинально христианскими морисками . Примерно через четыре десятилетия после войны в Альпухаррасе (1568–1571) более 300 000 морисков были изгнаны , поселившись в основном в Северной Африке. [40]

Объединение корон Арагона и Кастилии посредством брака их суверенов заложило основу для современной Испании и Испанской империи, хотя каждое королевство Испании оставалось отдельной страной в социальном, политическом, юридическом, а также в денежном и языковом отношении. [41] [42]

Габсбургская Испания была одной из ведущих мировых держав на протяжении XVI века и большей части XVII века, положение которой было укреплено торговлей и богатством колониальных владений, и она стала ведущей морской державой мира . Она достигла своего апогея во время правления первых двух испанских Габсбургов — Карла V/I (1516–1556) и Филиппа II (1556–1598). В этот период произошли Итальянские войны , Шмалькальденская война , Голландское восстание , Война за португальское наследство , столкновения с османами , вмешательство во французские религиозные войны и англо-испанская война . [43]

Благодаря разведке и завоеванию или королевским брачным союзам и наследованию Испанская империя расширилась на обширные территории в Америке, Индо-Тихоокеанском регионе, Африке, а также на европейском континенте (включая владения на итальянском полуострове, в Нидерландах и Франш -Конте ). Так называемая Эпоха Великих географических открытий характеризовалась исследованиями по морю и по суше, открытием новых торговых путей через океаны, завоеваниями и началом европейского колониализма . Драгоценные металлы , специи, предметы роскоши и ранее неизвестные растения, привезенные в метрополию, сыграли ведущую роль в трансформации европейского понимания земного шара. [44] Культурный расцвет, наблюдаемый в этот период, теперь называют Испанским золотым веком . Расширение империи вызвало огромные потрясения в Америке, поскольку крах обществ и империй и новые болезни из Европы опустошили коренное население Америки. Подъем гуманизма , Контрреформация и новые географические открытия и завоевания подняли вопросы, которые были рассмотрены интеллектуальным движением, ныне известным как Саламанкская школа , разработавшим первые современные теории того, что сейчас известно как международное право и права человека.

Морское превосходство Испании в XVI веке было продемонстрировано победой над Османской империей в битве при Лепанто в 1571 году и над Португалией в битве при Понта-Делгада в 1582 году, а затем, после поражения Испанской армады в 1588 году, серией побед над Англией в англо-испанской войне 1585–1604 годов . Однако в середине XVII века морская мощь Испании пришла в длительный упадок из-за растущих поражений от Голландской республики ( битва при Даунсе ), а затем от Англии в англо-испанской войне 1654–1660 годов ; к 1660-м годам она с трудом защищала свои заморские владения от пиратов и каперов.

Протестантская Реформация усилила участие Испании в религиозных войнах, заставив ее постоянно расширять военные усилия по всей Европе и в Средиземноморье. [45] К середине десятилетий войны и чумы в Европе XVII века испанские Габсбурги втянули страну в общеконтинентальные религиозно-политические конфликты. Эти конфликты истощили ее ресурсы и подорвали экономику в целом. Испании удалось удержать большую часть разрозненной империи Габсбургов и помочь имперским силам Священной Римской империи обратить вспять большую часть успехов, достигнутых протестантскими силами, но в конце концов она была вынуждена признать разделение Португалии и Соединенных провинций (Голландской республики) и в конечном итоге потерпела несколько серьезных военных поражений от Франции на последних этапах чрезвычайно разрушительной общеевропейской Тридцатилетней войны . [46] Во второй половине XVII века Испания постепенно пришла в упадок, в ходе которого она уступила несколько небольших территорий Франции и Англии; Однако ей удалось сохранить и расширить свою огромную заморскую империю, которая оставалась нетронутой до начала XIX века.

.jpg/440px-La_familia_de_Felipe_V_(Van_Loo).jpg)

Упадок достиг кульминации в споре о престолонаследии, который поглотил первые годы XVIII века. Война за испанское наследство была широкомасштабным международным конфликтом, совмещенным с гражданской войной, и должна была стоить королевству его европейских владений и его положения ведущей европейской державы. [47]

Во время этой войны была установлена новая династия, происходящая из Франции, Бурбоны . Короны Кастилии и Арагона долгое время были объединены только монархией и общим институтом Священной канцелярии инквизиции . [48] Монархия проводила ряд реформ (так называемые реформы Бурбонов ) с общей целью централизованной власти и административного единообразия. [49] Они включали отмену многих старых региональных привилегий и законов, [50] а также таможенного барьера между коронами Арагона и Кастилии в 1717 году, за которым последовало введение новых налогов на имущество в арагонских королевствах. [51]

XVIII век ознаменовался постепенным восстановлением и ростом благосостояния во многих частях империи. Преобладающей экономической политикой была интервенционистская политика, и государство также проводило политику, направленную на развитие инфраструктуры, а также отмену внутренних таможенных пошлин и снижение экспортных тарифов. [52] Проекты сельскохозяйственной колонизации с новыми поселениями имели место на юге материковой Испании. [53] Идеи Просвещения начали набирать силу среди части элиты королевства и монархии.

.jpg/440px-Fusilamiento_de_Torrijos_(Gisbert).jpg)

В 1793 году Испания вступила в войну против революционной новой Французской Республики в качестве члена первой коалиции . Последующая Пиренейская война поляризовала страну в ответ на галицизированные элиты, и после поражения на поле боя в 1795 году был заключен мир с Францией по Базельскому миру , в котором Испания потеряла контроль над двумя третями острова Эспаньола . В 1807 году секретный договор между Наполеоном и непопулярным премьер-министром привел к новому объявлению войны Великобритании и Португалии. Французские войска вошли в страну, чтобы вторгнуться в Португалию, но вместо этого заняли главные крепости Испании. Испанский король отрекся от престола, и было установлено марионеточное королевство-сателлит Французской империи с Жозефом Бонапартом в качестве короля.

Восстание 2 мая 1808 года было одним из многих восстаний по всей стране против французской оккупации. [54] Эти восстания ознаменовали начало разрушительной войны за независимость против наполеоновского режима. [55] Дальнейшие военные действия испанских армий, партизанская война и англо-португальская союзная армия в сочетании с неудачей Наполеона на русском фронте привели к отступлению французских имперских армий с Пиренейского полуострова в 1814 году и возвращению короля Фердинанда VII . [56]

Во время войны в 1810 году был собран революционный орган, Кортесы Кадиса , для координации усилий против бонапартистского режима и подготовки конституции. [57] Он собирался как единый орган, и его члены представляли всю Испанскую империю. [58] В 1812 году была провозглашена конституция всеобщего представительства в рамках конституционной монархии, но после падения бонапартистского режима испанский король распустил Генеральные кортесы, решив править как абсолютный монарх .

Французская оккупация материковой Испании создала возможность для заморских креольских элит, которые возмущались привилегиями полуостровных элит и требовали возврата суверенитета народу . Начиная с 1809 года американские колонии начали серию революций и объявили независимость, что привело к испано-американским войнам за независимость , положившим конец власти метрополии над Испанским Майном . Попытки восстановить контроль оказались тщетными из-за сопротивления не только в колониях, но и на Пиренейском полуострове, за чем последовали армейские восстания. К концу 1826 года единственными американскими колониями, которые удерживала Испания, были Куба и Пуэрто-Рико . Наполеоновская война оставила Испанию экономически разоренной, глубоко разделенной и политически нестабильной. В 1830-х и 1840-х годах карлизм (реакционное легитимистское движение, поддерживающее альтернативную ветвь Бурбонов) боролся против правительственных войск, поддерживающих династические права королевы Изабеллы II в Карлистских войнах . Правительственные силы одержали верх, но конфликт между прогрессистами и умеренными закончился слабым ранним конституционным периодом. За Славной революцией 1868 года последовало прогрессивное Сексенио Демократико 1868–1874 годов (включая недолговечную Первую Испанскую Республику ), которое уступило место стабильному монархическому периоду, Реставрации (1875–1931). [59]

В конце 19 века на Филиппинах и Кубе возникли националистические движения. В 1895 и 1896 годах вспыхнули Кубинская война за независимость и Филиппинская революция , в которую в конечном итоге вмешались Соединенные Штаты. Испано-американская война произошла весной 1898 года и привела к потере Испанией последней части своей некогда огромной колониальной империи за пределами Северной Африки. El Desastre (Катастро) — так война стала называться в Испании — дала дополнительный импульс поколению 98 года . Хотя период на рубеже веков был периодом растущего процветания, 20 век принес мало социального мира. Испания сыграла незначительную роль в борьбе за Африку . Она сохраняла нейтралитет во время Первой мировой войны . Тяжелые потери, понесенные колониальными войсками в конфликтах на севере Марокко против сил рифов, дискредитировали правительство и подорвали монархию.

Индустриализация, развитие железных дорог и зарождающийся капитализм развивались в нескольких районах страны, особенно в Барселоне , а также рабочее движение и социалистические и анархические идеи. Барселонский рабочий конгресс 1870 года и Барселонская всемирная выставка 1888 года являются хорошими примерами этого. В 1879 году была основана Испанская социалистическая рабочая партия . Профсоюз, связанный с этой партией, Unión General de Trabajadores , был основан в 1888 году. В анархо-синдикалистском направлении рабочего движения в Испании в 1910 году была основана Confederación Nacional del Trabajo , а в 1927 году — Federación Anarquista Ibérica .

В этот период в Испании, наряду с другими течениями национализма и регионализма, возникли каталонизм и васкизм: в 1895 году была образована Баскская националистическая партия , а в 1901 году — Регионалистская лига Каталонии .

Политическая коррупция и репрессии ослабили демократическую систему конституционной монархии с двухпартийной системой. [60] События и репрессии «Трагической недели» в июле 1909 года стали примером социальной нестабильности того времени.

Забастовка La Canadiense в 1919 году привела к принятию первого закона, ограничивающего рабочий день восемью часами. [61]

После периода поддерживаемой короной диктатуры с 1923 по 1931 год состоялись первые выборы с 1923 года, в значительной степени понимаемые как плебисцит по монархии: муниципальные выборы 12 апреля 1931 года . Они принесли убедительную победу республиканско-социалистическим кандидатам в крупных городах и провинциальных столицах, с большинством советников-монархистов в сельских районах. Король покинул страну, и 14 апреля последовало провозглашение Республики с формированием временного правительства.

Конституция страны была принята в октябре 1931 года после всеобщих учредительных выборов в июне 1931 года , и последовал ряд кабинетов под председательством Мануэля Асаньи, поддержанных республиканскими партиями и ИСРП . На выборах, состоявшихся в 1933 году, победили правые, а в 1936 году — левые. Во время Второй республики произошел большой политический и социальный переворот, отмеченный резкой радикализацией левых и правых. Случаи политического насилия в этот период включали поджоги церквей, неудавшийся государственный переворот 1932 года под руководством Хосе Санхурхо , Революцию 1934 года и многочисленные нападения на конкурирующих политических лидеров. С другой стороны, именно во время Второй республики были инициированы важные реформы по модернизации страны: демократическая конституция, аграрная реформа, реструктуризация армии, политическая децентрализация и право голоса для женщин .

Гражданская война в Испании началась в 1936 году: 17 и 18 июля часть военных совершила государственный переворот , который одержал победу только в части страны. Ситуация привела к гражданской войне, в которой территория была разделена на две зоны: одна под властью республиканского правительства , которое рассчитывало на внешнюю поддержку со стороны Советского Союза и Мексики (и от Интернациональных бригад ), и другая, контролируемая путчистами ( Националистической или повстанческой фракцией ), наиболее критически поддерживаемой нацистской Германией и фашистской Италией . Республика не была поддержана западными державами из-за проводимой Великобританией политики невмешательства . Генерал Франсиско Франко был приведен к присяге в качестве верховного лидера повстанцев 1 октября 1936 года. Также последовали непростые отношения между республиканским правительством и низовыми анархистами, которые инициировали частичную социальную революцию .

Гражданская война была жестокой, и было совершено много зверств всеми сторонами . Война унесла жизни более 500 000 человек и привела к бегству из страны до полумиллиона граждан. [62] [63] 1 апреля 1939 года, за пять месяцев до начала Второй мировой войны , повстанческая сторона во главе с Франко одержала победу, установив диктатуру во всей стране. Тысячи людей были заключены после гражданской войны во франкистские концентрационные лагеря .

Режим оставался номинально «нейтральным» большую часть Второй мировой войны, хотя он симпатизировал странам Оси и поставлял нацистскому вермахту испанских добровольцев на Восточном фронте . Единственной легальной партией при диктатуре Франко была Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS (FET y de las JONS), образованная в 1937 году в результате слияния Falange Española de las JONS и традиционалистов-карлистов, к которой также присоединились остальные правые группы, поддерживавшие повстанцев. Название « Movimiento Nacional », иногда понимаемое как более широкая структура, чем собственно FET y de las JONS, в значительной степени накладывалось на название последнего в официальных документах 1950-х годов.

.jpg/440px-Meeting_at_Hendaye_(en.wiki).jpg)

После войны Испания была политически и экономически изолирована и не входила в Организацию Объединенных Наций. Это изменилось в 1955 году, в период холодной войны , когда для США стало стратегически важным установить военное присутствие на Пиренейском полуострове в качестве противовеса любому возможному шагу Советского Союза в Средиземноморский бассейн. Стратегические приоритеты США в период холодной войны включали распространение американских образовательных идей для содействия модернизации и расширению. [64] В 1960-х годах Испания зарегистрировала беспрецедентные темпы экономического роста , которые были обусловлены индустриализацией , массовой внутренней миграцией из сельских районов в Мадрид , Барселону и Страну Басков и созданием массовой туристической индустрии. Правление Франко также характеризовалось авторитаризмом , продвижением унитарной национальной идентичности , национальным католицизмом и дискриминационной языковой политикой .

В 1962 году группа политиков, участвовавших в оппозиции режиму Франко внутри страны и в изгнании, встретилась на конгрессе Европейского движения в Мюнхене, где они приняли резолюцию в пользу демократии. [65] [66] [67]

Со смертью Франко в ноябре 1975 года Хуан Карлос унаследовал пост короля Испании и главы государства в соответствии с франкистским законом. С принятием новой испанской конституции 1978 года и восстановлением демократии государство передало большую часть полномочий регионам и создало внутреннюю организацию, основанную на автономных сообществах . Испанский закон об амнистии 1977 года позволил людям режима Франко продолжать работу в учреждениях без последствий, даже виновным в некоторых преступлениях во время перехода к демократии, таких как резня 3 марта 1976 года в Витории или резня 1977 года на Аточе .

В Стране Басков умеренный баскский национализм сосуществовал с радикальным националистическим движением во главе с вооруженной организацией ЭТА до ее роспуска в мае 2018 года. [68] Группа была сформирована в 1959 году во время правления Франко, но продолжала вести свою жестокую кампанию даже после восстановления демократии и возвращения значительной части региональной автономии.

23 февраля 1981 года мятежные элементы среди сил безопасности захватили Кортесы в попытке навязать поддерживаемое военными правительство . Король Хуан Карлос лично взял под свое командование армию и успешно приказал заговорщикам сдаться через национальное телевидение. [69]

В 1980-х годах демократическое восстановление сделало возможным рост открытого общества. Появились новые культурные движения, основанные на свободе, такие как La Movida Madrileña . В мае 1982 года Испания вступила в НАТО , за чем последовал референдум после сильного социального сопротивления. В том же году к власти пришла Испанская социалистическая рабочая партия (ИСРП), первое левое правительство за 43 года. В 1986 году Испания вступила в Европейское экономическое сообщество , которое позже стало Европейским союзом . В 1996 году ИСРП была заменена в правительстве Народной партией (ПП) после скандалов, связанных с участием правительства Фелипе Гонсалеса в Грязной войне против ЭТА .

1 января 2002 года Испания полностью перешла на евро , и в стране наблюдался сильный экономический рост, значительно превышающий средний показатель по ЕС в начале 2000-х годов. Однако широко освещаемые опасения многих экономических комментаторов на пике бума предупреждали, что чрезвычайные цены на недвижимость и высокий дефицит внешней торговли, скорее всего, приведут к болезненному экономическому краху. [70]

В 2002 году произошел разлив нефти Prestige с большими экологическими последствиями вдоль атлантического побережья Испании. В 2003 году Хосе Мария Аснар поддержал президента США Джорджа Буша-младшего в войне в Ираке , и в испанском обществе возникло сильное движение против войны. В марте 2004 года местная исламистская террористическая группировка, вдохновленная Аль-Каидой, совершила крупнейший теракт в истории Западной Европы, когда они убили 191 человека и ранили более 1800 других, взорвав пригородные поезда в Мадриде. [71] Хотя первоначальные подозрения были сосредоточены на баскской террористической группировке ETA , вскоре появились доказательства участия исламистов. Из-за близости всеобщих выборов в Испании 2004 года вопрос ответственности быстро превратился в политический спор, и основные конкурирующие партии PP и PSOE обменялись обвинениями по поводу урегулирования инцидента. [72] Выборы выиграла PSOE во главе с Хосе Луисом Родригесом Сапатеро . [73]

В начале 2000-х годов доля населения Испании, родившегося за рубежом, быстро росла во время экономического бума, но затем снизилась из-за финансового кризиса. [74] В 2005 году правительство Испании легализовало однополые браки , став третьей страной в мире, сделавшей это. [75] Децентрализация была поддержана большим сопротивлением Конституционного суда и консервативной оппозиции, как и гендерная политика, такая как квоты или закон против гендерного насилия. Состоялись правительственные переговоры с ETA, и группа объявила о своем постоянном прекращении насилия в 2010 году. [76]

Лопнувший в 2008 году испанский пузырь недвижимости привёл к испанскому финансовому кризису 2008–16 годов . Высокий уровень безработицы, сокращение государственных расходов и коррупция в королевской семье и Народной партии послужили фоном для протестов в Испании 2011–12 годов . [77] Каталонская независимость также возросла. В 2011 году консервативная Народная партия Мариано Рахоя победила на выборах, набрав 44,6% голосов. [78] Будучи премьер-министром, он ввёл меры жёсткой экономии для спасения ЕС, Пакт стабильности и роста ЕС. [79] 19 июня 2014 года монарх Хуан Карлос отрёкся от престола в пользу своего сына, который стал Фелипе VI . [80]

В октябре 2017 года был проведен референдум о независимости Каталонии , и парламент Каталонии проголосовал за одностороннее провозглашение независимости от Испании и образование Каталонской Республики [81] [82] в тот день, когда Сенат Испании обсуждал одобрение прямого правления в Каталонии, к которому призвал премьер-министр Испании. [83] [84] В тот же день Сенат предоставил полномочия на введение прямого правления, а Рахой распустил парламент Каталонии и назначил новые выборы. [85] Ни одна страна не признала Каталонию отдельным государством. [86]

_-_1.jpg/440px-Primera_trobada_entre_el_president_Illa_i_l'alcalde_Collboni_(23-08-2024)_-_1.jpg)

В июне 2018 года Конгресс депутатов принял вотум недоверия Рахою и заменил его лидером ИСРП Педро Санчесом . [87] В 2019 году было сформировано первое в истории Испании коалиционное правительство между ИСРП и Unidas Podemos. В период с 2018 по 2024 год Испания столкнулась с институциональным кризисом , связанным с мандатом Генерального совета судебной власти (CGPJ), пока мандат, наконец, не был обновлен. [88] В январе 2020 года было подтверждено, что вирус COVID-19 распространился в Испании , в результате чего продолжительность жизни сократилась более чем на год. [89] Пакет мер Европейской комиссии по экономическому восстановлению Next Generation EU был создан для поддержки государств-членов ЕС в восстановлении после пандемии COVID-19 и будет использоваться в период 2021–2026 годов. В марте 2021 года Испания стала шестой страной в мире, легализовавшей активную эвтаназию . [90] После всеобщих выборов 23 июля 2023 года премьер-министр Педро Санчес снова сформировал коалиционное правительство, на этот раз с Сумаром (преемником Unidas Podemos ). [91] В 2024 году был избран первый за более чем десятилетие независимый каталонский региональный президент Сальвадор Илья , что нормализовало конституционные и институциональные отношения между национальной и региональной администрациями. Согласно последним опросам, [92] только 17,3% каталонцев чувствуют себя «только каталонцами». 46% каталонцев ответили бы «столь же испанцы, как каталонцы», а 21,8% «более каталонцы, чем испанцы». [93] Согласно опросу, проведенному в 2024 году Университетом Барселоны, более 50% каталонцев проголосовали бы против независимости, в то время как менее 40% проголосовали бы за. [94]

С площадью 505 992 км 2 (195 365 кв. миль) Испания является пятьдесят первой по величине страной в мире и четвертой по величине страной в Европе . Она примерно на 47 000 км 2 (18 000 кв. миль) меньше Франции. С высотой 3715 м (12 188 футов) гора Тейде ( Тенерифе ) является самой высокой горной вершиной в Испании и третьим по величине вулканом в мире от своего основания. Испания является трансконтинентальной страной , имеющей территорию как в Европе , так и в Африке .

Испания расположена между 27° и 44° северной широты и 19° западной долготы и 5° восточной долготы .

На западе Испания граничит с Португалией ; на юге — с Гибралтаром и Марокко через свои эксклавы в Северной Африке ( Сеута и Мелилья , а также полуостров Велес-де-ла-Гомера ). На северо-востоке, вдоль Пиренейского хребта, она граничит с Францией и Андоррой . Вдоль Пиренеев в Жироне небольшой эксклавный городок Льивия окружен Францией.

Протяженность границы Португалии и Испании составляет 1214 км (754 мили), что делает ее самой длинной непрерывной границей в Европейском Союзе . [95]

Испания также включает Балеарские острова в Средиземном море , Канарские острова в Атлантическом океане и ряд необитаемых островов на средиземноморской стороне Гибралтарского пролива , известных как plazas de soberanía («места суверенитета» или территории под испанским суверенитетом), такие как острова Чафаринас и Альусемас . Полуостров Велес-де-ла-Гомера также считается plaza de soberanía . Остров Альборан , расположенный в Средиземном море между Испанией и Северной Африкой, также управляется Испанией, в частности муниципалитетом Альмерия , Андалусия. Маленький остров Фазана на реке Бидасоа является испано-французским кондоминиумом .

В Испании 11 крупных островов, все из которых имеют свои собственные органы управления ( Cabildos insulares на Канарских островах, Consells insulares на Балеарских островах). Эти острова специально упомянуты в Конституции Испании при установлении ее сенаторского представительства (Ибица и Форментера сгруппированы, поскольку вместе они образуют Питиусские острова , часть Балеарского архипелага). К этим островам относятся Тенерифе , Гран-Канария , Лансароте , Фуэртевентура , Ла-Пальма , Ла-Гомера и Эль-Йерро на Канарском архипелаге и Майорка , Ибица , Менорка и Форментера на Балеарском архипелаге.

.jpg/440px-Teide_von_Nordosten_(Zuschnitt_1).jpg)

Материковая Испания — довольно гористая местность, на которой преобладают высокие плато и горные цепи. После Пиренеев основными горными хребтами являются Кантабрийская Кордильера (Кантабрийский хребет), Иберийская система (Иберийская система), Центральная система (Центральная система), Монтес-де-Толедо , Сьерра-Морена и Бетико (Баетическая система), самая высокая вершина которой, Муласен высотой 3478 метров (11411 футов) , расположенный в Сьерра-Неваде , является самой высокой точкой Пиренейского полуострова. Самая высокая точка Испании — Тейде , действующий вулкан высотой 3718 метров (12198 футов) на Канарских островах. Центральное плато (часто переводимое как «Внутреннее плато») — обширное плато в самом сердце полуостровной Испании, разделенное на две части Центральной системой.

В Испании есть несколько крупных рек, таких как Тежу ( Тахо ), Эбро , Гвадиана , Дору ( Дуэро ), Гвадалквивир , Хукар , Сегура , Турия и Миньо ( Миньо ). Вдоль побережья расположены аллювиальные равнины , самая большая из которых — Гвадалквивир в Андалусии .

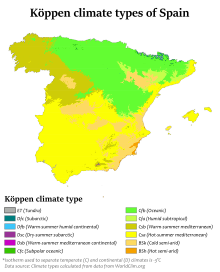

В зависимости от географического положения и орографических условий можно выделить три основные климатические зоны : [96]

Помимо этих основных типов, можно найти и другие подтипы, такие как альпийский климат в районах с очень большой высотой, влажный субтропический климат в районах северо-восточной Испании и континентальный климат ( Dfc , Dfb / Dsc , Dsb ) в Пиренеях , а также в частях Кантабрийского хребта , Центральной системы , Сьерра-Невады и Иберийской системы , и типичный пустынный климат ( BWk , BWh ) в зоне Альмерии , Мурсии и восточных Канарских островов . Низменные районы Канарских островов в среднем имеют температуру выше 18,0 °C (64,4 °F) в течение самого холодного месяца, таким образом, имея влияние тропического климата , хотя их нельзя должным образом классифицировать как тропический климат, так как, согласно AEMET, их засушливость высока, поэтому они относятся к засушливому или полузасушливому климату. [97]

Испания является одной из стран, наиболее пострадавших от климатического кризиса в Европе. Испания может увидеть потепление на 2 °C (3,6 °F) по сравнению с доиндустриальным уровнем в течение следующих двадцати лет, в худшем случае Испания достигнет потепления на 4 °C (7,2 °F) к концу столетия. Из-за снижения количества осадков засухи в Испании, которые и так являются одними из самых сильных в Европе, будут в десять раз сильнее по сравнению с 2023 годом. ВОЗ подсчитала , что в 2022 году из-за стресса, связанного с жарой, в Испании погибло 4000 человек. [98] 74% страны подвержены риску опустынивания [99]

Выбросы на душу населения в Испании составили 4,92 тонны в 2021 году, что примерно на 1,5 тонны ниже среднего показателя по ЕС. В 2021 году на Испанию приходилось 0,87% совокупных мировых выбросов. Испания взяла на себя обязательство сократить выбросы на 23% по сравнению с уровнем 1990 года в 2030 году и достичь нулевого уровня в 2050 году. [100]

Фауна отличается большим разнообразием, что во многом обусловлено географическим положением Пиренейского полуострова между Атлантикой и Средиземным морем, а также между Африкой и Евразией , а также большим разнообразием местообитаний и биотопов , что является результатом значительного разнообразия климатических условий и четкой дифференциации регионов.

Растительность Испании разнообразна из-за нескольких факторов, включая разнообразие рельефа, климата и широты . Испания включает в себя различные фитогеографические регионы, каждый из которых имеет свои собственные флористические характеристики, являющиеся в значительной степени результатом взаимодействия климата, топографии, типа почвы и пожаров, а также биотических факторов. Средний балл Индекса целостности лесного ландшафта страны за 2019 год составил 4,23/10, что ставит ее на 130-е место в мире из 172 стран. [101]

На территории Европы Испания имеет самое большое количество видов растений (7600 сосудистых растений) среди всех европейских стран. [102]

В Испании растёт 17,804 миллиарда деревьев, и в среднем каждый год вырастает ещё 284 миллиона. [103]

Конституционная история Испании восходит к конституции 1812 года. В июне 1976 года новый король Испании Хуан Карлос отправил в отставку Карлоса Ариаса Наварро и назначил реформатора Адольфо Суареса премьер-министром. [104] [105] В результате всеобщих выборов 1977 года были созваны Учредительные кортесы (испанский парламент в качестве конституционного собрания) с целью разработки и утверждения конституции 1978 года. [106] После общенационального референдума 6 декабря 1978 года 88% избирателей одобрили новую конституцию. В результате Испания успешно перешла от однопартийной персоналистской диктатуры к многопартийной парламентской демократии, состоящей из 17 автономных сообществ и двух автономных городов . Эти регионы пользуются различной степенью автономии благодаря испанской конституции, которая, тем не менее, прямо заявляет о неделимом единстве испанской нации.

Независимость Короны, ее политический нейтралитет и ее стремление принять и примирить различные идеологические точки зрения позволяют ей вносить вклад в стабильность нашей политической системы, способствуя достижению баланса с другими конституционными и территориальными органами, содействуя упорядоченному функционированию государства и предоставляя канал для сплочения испанцев. [107]

Король Филипп VI , 2014 г.

Конституция Испании предусматривает разделение властей между пятью ветвями власти , которые она называет «основными государственными институтами». [k] [108] [109] Главным среди этих институтов является Корона ( La Corona ), символ испанского государства и его постоянства. [110] «Парламентская монархия» Испании является конституционной , в которой правящий король или королева являются живым воплощением Короны и, таким образом, главой государства . [l] [111] [110] [112] Однако, в отличие от некоторых других конституционных монархий, а именно таких, как Бельгия , Дания , Люксембург , Нидерланды , Норвегия или даже Соединенное Королевство , монарх не является источником национального суверенитета или даже номинальным главой исполнительной власти . [113] [114] [115] [116] [117] [118] Скорее, Корона, как институт, «...выступает арбитром и смягчает регулярное функционирование институтов...» испанского государства. [110] Как таковой, монарх разрешает споры между разрозненными ветвями власти, выступает посредником в конституционных кризисах и предотвращает злоупотребления властью . [119] [120] [121] [122]

В этом отношении Корона представляет собой пятую регулирующую ветвь власти , которая не разрабатывает государственную политику и не управляет государственными службами , функции, которые по праву принадлежат законно избранным законодательным органам и правительствам Испании как на национальном, так и на региональном уровне. Вместо этого Корона олицетворяет демократическое испанское государство, санкционирует законную власть, обеспечивает законность средств и гарантирует исполнение общественной воли. [123] [124] Иными словами, монарх способствует национальному единству дома, представляет испанцев за рубежом (особенно в отношении наций их исторического сообщества ), способствует упорядоченной работе и преемственности испанского правительства , защищает представительную демократию и поддерживает верховенство закона . [109] Другими словами, Корона является хранителем испанской конституции и прав и свобод всех испанцев. [125] [м] Эта стабилизирующая роль соответствует торжественной клятве монарха при вступлении на престол : «... добросовестно исполнять [мои] обязанности, соблюдать Конституцию и законы и обеспечивать их соблюдение, а также уважать права граждан и самоуправляющихся сообществ». [127]

Монарху в качестве главы государства возлагается ряд конституционных полномочий, обязанностей, прав, ответственности и функций. Однако Корона пользуется неприкосновенностью при исполнении этих прерогатив и не может преследоваться в тех же судах, которые отправляют правосудие от ее имени. [128] По этой причине каждый официальный акт, совершенный монархом, требует контрассигнации премьер -министра или, в соответствующих случаях, президента Конгресса депутатов , чтобы иметь силу закона. Процедура контрассигнации или refrendo, в свою очередь, передает политическую и юридическую ответственность за королевскую прерогативу удостоверяющим сторонам. [129] Это положение не распространяется на Королевский двор , над которым монарх имеет абсолютный контроль и надзор, или на членство в Ордене Золотого руна , который является династическим орденом в личном даре Дома Бурбонов-Анжу . [130]

Королевские прерогативы можно классифицировать по тому, являются ли они министерскими актами или резервными полномочиями. Министерские акты — это те королевские прерогативы, которые в соответствии с конвенцией, установленной Хуаном Карлосом I , выполняются монархом после запроса совета правительства, Конгресса депутатов, Сената, Генерального совета судебной власти или Конституционного трибунала, в зависимости от обстоятельств. С другой стороны, резервные полномочия Короны — это те королевские прерогативы, которые осуществляются по личному усмотрению монарха. [125] Большинство королевских прерогатив Короны на практике являются министерскими, то есть монарх не имеет дискреционных полномочий в их исполнении и в первую очередь выполняет их как вопрос государственной церемонии. [p] Тем не менее, при выполнении указанных министерских актов монарх имеет право на консультацию перед тем, как действовать по совету, право поощрять определенный курс действий и право предупреждать ответственные конституционные органы.

Вышеуказанные ограничения не распространяются на резервные полномочия Короны, которые могут быть использованы монархом при необходимости поддержания преемственности и стабильности государственных институтов. [150] Например, монарх имеет право быть информированным о государственных делах посредством регулярных аудиенций в правительстве. С этой целью монарх может в любое время председательствовать на заседаниях Совета министров, но только по просьбе премьер-министра. [151] Более того, монарх может досрочно распустить Конгресс депутатов, Сенат или обе палаты Кортесов в полном составе до истечения их четырехлетнего срока и, вследствие этого, одновременно назначить внеочередные выборы . Монарх осуществляет эту прерогативу по просьбе премьер-министра после обсуждения вопроса Советом министров. Монарх может принять решение о принятии или отклонении просьбы. [152] Монарх может также назначить общенациональные референдумы по просьбе премьер-министра, но только с предварительного разрешения Генеральных кортесов. Опять же, монарх может принять или отклонить просьбу премьер-министра. [153]

Резервные полномочия Короны распространяются далее на толкование конституции и отправление правосудия . Монарх назначает 20 членов Генерального совета судебной власти . Из этих советников двенадцать назначаются верховным, апелляционным и судами первой инстанции, четыре назначаются Конгрессом депутатов большинством в три пятых его членов, и четыре назначаются Сенатом с таким же большинством. Монарх может принять решение принять или отклонить любую кандидатуру. [154] В аналогичном ключе монарх назначает двенадцать магистратов Конституционного трибунала . Из этих магистратов четыре магистрата назначаются Конгрессом депутатов большинством в три пятых его членов, четыре магистрата назначаются Сенатом с таким же большинством, два магистрата назначаются правительством, и два магистрата назначаются Генеральным советом судебной власти. Монарх может принять решение принять или отклонить любую кандидатуру. [155]

Однако, возможно, наиболее часто используются резервные полномочия монарха в отношении формирования правительства . Монарх выдвигает кандидата на пост премьер-министра и, в зависимости от обстоятельств, назначает или отстраняет его или ее от должности, исходя из способности премьер-министра поддерживать доверие Конгресса депутатов . [ 156] Если Конгресс депутатов не вынесет своего доверия новому правительству в течение двух месяцев и, таким образом, окажется неспособным управлять в результате парламентского тупика, монарх может распустить Генеральные кортесы и назначить новые выборы. Монарх использует эти резервные полномочия по своему собственному совещательному решению после консультации с президентом Конгресса депутатов. [157]

Законодательная власть принадлежит Cortes Generales (английский: Spanish Parliament , букв. «Генеральные суды»), демократически избранному двухпалатному парламенту , который служит высшим представительным органом испанского народа. Помимо Короны, это единственный основной государственный институт, который пользуется неприкосновенностью. [158] Он состоит из Конгресса депутатов ( Congreso de los Diputados ), нижней палаты с 350 депутатами, и Сената ( Senado ), верхней палаты с 259 сенаторами. [159] [160] Депутаты избираются всенародным голосованием по закрытым спискам через пропорциональное представительство на четырехлетний срок. [161] С другой стороны, 208 сенаторов избираются напрямую всенародным голосованием с использованием метода ограниченного голосования , а оставшиеся 51 сенатор назначаются региональными законодательными органами также на четырехлетний срок. [162]

Исполнительная власть принадлежит правительству ( Gobierno de España ), которое несет коллективную ответственность перед Конгрессом депутатов. [163] [164] Оно состоит из премьер-министра , одного или нескольких заместителей премьер-министра и различных государственных министров . [165] Эти лица вместе составляют Совет министров , который, как центральный исполнительный орган Испании , ведет дела правительства и управляет государственной службой . [166] Правительство остается у власти до тех пор, пока оно может поддерживать доверие Конгресса депутатов.

Премьер-министр, как глава правительства , пользуется приоритетом над другими министрами в силу своей способности давать советы монарху относительно их назначения и увольнения. [167] Более того, премьер-министр имеет все полномочия, предоставленные Конституцией Испании, для руководства и координации политики правительства и административных действий. [168] Испанский монарх назначает премьер-министра после консультаций с представителями различных парламентских групп и, в свою очередь, официально назначает его или ее на должность путем голосования по вступлению в должность в Конгрессе депутатов. [169]

Автономные сообщества Испании являются первым уровнем административного деления страны. Они были созданы после вступления в силу действующей конституции (в 1978 году) в знак признания права на самоуправление «национальностей и регионов Испании ». [170] Автономные сообщества должны были включать смежные провинции с общими историческими, культурными и экономическими чертами. Эта территориальная организация, основанная на деволюции , известна в Испании как «Государство автономий» ( Estado de las Autonomías ). Основным институциональным законом каждого автономного сообщества является Устав автономии . Устав автономии устанавливает название сообщества в соответствии с его исторической и современной идентичностью, границы его территорий, название и организацию институтов управления и права, которыми они пользуются в соответствии с конституцией. [171] Этот продолжающийся процесс деволюции означает, что, хотя официально Испания является унитарным государством , тем не менее она является одной из самых децентрализованных стран в Европе, наряду с такими федерациями , как Бельгия , Германия и Швейцария . [172]

Каталония, Галисия и Страна Басков, которые идентифицировали себя как национальности , получили самоуправление в результате быстрого процесса. Андалусия также идентифицировала себя как национальность в своем первом Статуте об автономии, хотя она следовала более длительному процессу, предусмотренному в конституции для остальной части страны. Постепенно другие сообщества в пересмотре своих Статутов об автономии также приняли это наименование в соответствии со своей исторической и современной идентичностью, например, Валенсийское сообщество, [173] Канарские острова, [174] Балеарские острова, [175] и Арагон. [176]

Автономные сообщества имеют широкую законодательную и исполнительную автономию, с их собственными избранными парламентами и правительствами, а также собственными специализированными государственными администрациями . Распределение полномочий может быть различным для каждого сообщества, как изложено в их Статутах автономии, поскольку передача полномочий была задумана как асимметричная. Например, только два сообщества — Страна Басков и Наварра — имеют полную фискальную автономию, основанную на древних положениях foral . Тем не менее, каждое автономное сообщество отвечает за здравоохранение и образование, среди других государственных услуг. [177] Помимо этих компетенций, национальности — Андалусия , Страна Басков , Каталония и Галисия — также получили больше полномочий, чем остальные сообщества, среди них право регионального президента распускать парламент и назначать выборы в любое время. Кроме того, Страна Басков, Канарские острова , Каталония и Наварра имеют собственные автономные полицейские корпуса: Ertzaintza , Policía Canaria , Mossos d'Esquadra и Policía Foral соответственно. Другие сообщества имеют более ограниченные силы или вообще не имеют их, как Policía Autónoma Andaluza в Андалусии или BESCAM в Мадриде. [178]

Автономные сообщества делятся на провинции , которые служат их территориальными строительными блоками. В свою очередь, провинции делятся на муниципалитеты . Существование как провинций, так и муниципалитетов гарантируется и защищается конституцией, а не обязательно самими Уставами автономии. Муниципалитетам предоставляется автономия для управления своими внутренними делами, а провинции являются территориальными подразделениями, призванными осуществлять деятельность государства. [179]

Текущая структура провинциального деления основана — с небольшими изменениями — на территориальном делении 1833 года Хавьера де Бургоса , и в целом испанская территория разделена на 50 провинций. Сообщества Астурия, Кантабрия, Ла-Риоха, Балеарские острова, Мадрид, Мурсия и Наварра являются единственными сообществами, которые составляют одну провинцию, которая совпадает с самим сообществом. В этих случаях административные институты провинции заменяются правительственными институтами сообщества.

.jpg/440px-Barcelona_Palau_Reial_de_Pedralbes_(51135781861).jpg)

После восстановления демократии после смерти Франко в 1975 году приоритетами внешней политики Испании стали выход из дипломатической изоляции времен Франко и расширение дипломатических отношений , вступление в Европейское сообщество и определение отношений в сфере безопасности с Западом.

Будучи членом НАТО с 1982 года, Испания зарекомендовала себя как участник многосторонних международных мероприятий по безопасности. Членство Испании в ЕС является важной частью ее внешней политики. Даже по многим международным вопросам за пределами Западной Европы Испания предпочитает координировать свои усилия с партнерами по ЕС через европейские механизмы политического сотрудничества. [ неопределенно ]

Испания сохранила особые отношения с испаноязычной Америкой и Филиппинами . Ее политика подчеркивает концепцию иберо-американского сообщества, по сути, обновление концепции « Hispanidad » или « Hispanismo » , как ее часто называют в английском языке, которая стремится связать Пиренейский полуостров с испаноязычной Америкой посредством языка, торговли, истории и культуры. Она в своей основе «основана на общих ценностях и восстановлении демократии». [180]

Страна вовлечена в ряд территориальных споров . Испания претендует на Гибралтар , заморскую территорию Соединенного Королевства , в самой южной части Пиренейского полуострова. [181] [182] [183] Другой спор касается островов Дикарей ; Испания утверждает, что это скалы, а не острова, и поэтому не принимает португальскую исключительную экономическую зону (200 морских миль), созданную островами. [184] [185] Испания претендует на суверенитет над островом Перехиль , небольшим необитаемым скалистым островком , расположенным на южном берегу Гибралтарского пролива ; он был предметом вооруженного инцидента между Испанией и Марокко в 2002 году. Марокко претендует на испанские города Сеута и Мелилья и островки Пласас-де-Соберания у северного побережья Африки. Португалия не признает суверенитет Испании над территорией Оливенса . [186]

_underway_in_the_Adriatic_Sea,_22_February_2023_(230222-N-MW880-1248).JPG/440px-Spanish_amphibious_assault_ship_Juan_Carlos_I_(L-61)_underway_in_the_Adriatic_Sea,_22_February_2023_(230222-N-MW880-1248).JPG)

Вооруженные силы Испании разделены на три рода войск: армия ( Ejército de Tierra ) ; Военно-Морской Флот ( Армада ) ; и Воздушно-космические силы ( Ejército del Aire y del Espacio ) . [187]

_and_other_North_Atlantic_Treaty_Organization_(NATO)_leaders_at_the_NATO_Summit_in_Madrid,_June_29–30,_2022_-_IMG_2325.jpg/440px-thumbnail.jpg)

Вооруженные силы Испании известны как Вооруженные силы Испании ( Fuerzas Armadas Españolas ). Их главнокомандующим является король Испании Филипп VI . [188] Следующими военными властями являются премьер-министр и министр обороны. Четвертым военным органом государства является начальник штаба обороны (JEMAD). [189] Штаб обороны ( Estado Mayor de la Defensa ) оказывает помощь JEMAD в качестве вспомогательного органа.

Вооруженные силы Испании являются профессиональными силами, численность которых в 2017 году составляла 121 900 человек действующего состава и 4770 человек резерва. В стране также есть 77 000 человек Гражданской гвардии , которая переходит под контроль Министерства обороны во время чрезвычайного положения в стране. Бюджет обороны Испании составляет 5,71 млрд евро (7,2 млрд долларов США), что на 1% больше, чем в 2015 году. Увеличение связано с проблемами безопасности в стране. [190] Военная повинность была отменена в 2001 году. [191]

Согласно Глобальному индексу миролюбия 2024 года , Испания является 23-й самой миролюбивой страной в мире. [192]

Конституция Испании 1978 года «защищает всех испанцев и все народы Испании в осуществлении прав человека, их культуру и традиции, языки и институты». [193]

По данным Amnesty International (AI), правительственные расследования предполагаемых злоупотреблений со стороны полиции часто бывают длительными, а наказания — мягкими. [194] Насилие в отношении женщин было проблемой, и правительство приняло меры для ее решения. [195] [196]

Испания предоставляет одну из самых высоких степеней свободы в мире для своего сообщества ЛГБТ . Среди стран, изученных Pew Research Center в 2013 году, Испания занимает первое место по принятию гомосексуализма, 88% опрошенных заявили, что гомосексуализм следует принимать. [197]

The Cortes Generales approved the Gender Equality Act in 2007 aimed at furthering equality between genders in Spanish political and economic life.[198] According to Inter-Parliamentary Union data as of 1 September 2018, 137 of the 350 members of the Congress were women (39.1%), while in the Senate, there were 101 women out of 266 (39.9%), placing Spain 16th on their list of countries ranked by proportion of women in the lower (or single) House.[199] The Gender Empowerment Measure of Spain in the United Nations Human Development Report is 0.794, 12th in the world.[200]

.jpg/440px-20140404193229!Cuatro_Torres_Business_Area_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg/440px-Torre_Glòries,_Barcelona_(51351746585).jpg)

Spain's capitalist mixed economy is the 15th largest worldwide and the 4th largest in the European Union, as well as the eurozone's 4th largest. The centre-right government of former prime minister José María Aznar worked successfully to gain admission to the group of countries launching the euro in 1999. Unemployment stood at 11.27% in July 2024.[201] The youth unemployment rate (26.5% in April 2024) is extremely high compared to EU standards.[202] Perennial weak points of Spain's economy include a large informal economy,[203][204][205] and an education system which OECD reports place among the poorest for developed countries, along with the United States.[206]

Since the 1990s some Spanish companies have gained multinational status, often expanding their activities in culturally close Latin America. Spain is the second biggest foreign investor there, after the United States. Spanish companies have also expanded into Asia, especially China and India.[207] Spanish companies invested in fields like renewable energy commercialisation (Iberdrola was the world's largest renewable energy operator[208]), technology companies like Telefónica, Abengoa, Mondragon Corporation (which is the world's largest worker-owned cooperative), Movistar, Hisdesat, Indra, train manufacturers like CAF, Talgo, global corporations such as the textile company Inditex, petroleum companies like Repsol or Cepsa and infrastructure, with six of the ten biggest international construction firms specialising in transport being Spanish, like Ferrovial, Acciona, ACS, OHL and FCC.[209]

The automotive industry in Spain is one of the largest employers in the country. In 2023, Spain produced 2.45 million cars which makes it the 8th largest automobile producer country in the world and the 2nd largest car manufacturer in Europe after Germany,[210] a position in the ranking that it was still keeping in 2024.[211] In total, 89% of the vehicles and 60% of the auto-parts manufactured in Spain were exported worldwide in 2023. A total of 2,201,802 made in Spain vehicles were exported in 2023. In 2023, the Spanish automotive industry generated 10% of Spain's gross domestic product and accounted for 18% of total Spanish exports (including vehicles and auto-parts). External trade surplus of vehicles reached €18.8bn in 2023. The industry generates 9% of total employment, nearly 2 million jobs are linked to this industry.[210]

In 2023, Spain was the second most visited country in the world only behind France, recording 85 million tourists. The headquarters of the World Tourism Organization are located in Madrid.

Spain's geographic location, popular coastlines, diverse landscapes, historical legacy, vibrant culture, and excellent infrastructure have made the country's international tourist industry among the largest in the world. In the last five decades, international tourism in Spain has grown to become the second largest in the world in terms of spending, worth approximately 40 billion Euros or about 5% of GDP in 2006.[212][213]

Castile and Leon is the Spanish leader in rural tourism linked to its environmental and architectural heritage.

In 2010 Spain became the solar power world leader when it overtook the United States with a massive power station plant called La Florida, near Alvarado, Badajoz.[214][215] Spain is also Europe's main producer of wind energy.[216][217] In 2010 its wind turbines generated 16.4% of all electrical energy produced in Spain.[218][219][220] On 9 November 2010, wind energy reached a historic peak covering 53% of mainland electricity demand[221] and generating an amount of energy that is equivalent to that of 14 nuclear reactors.[222] Other renewable energies used in Spain are hydroelectric, biomass and marine.[223]

Non-renewable energy sources used in Spain are nuclear (8 operative reactors), gas, coal, and oil. Fossil fuels together generated 58% of Spain's electricity in 2009, just below the OECD mean of 61%. Nuclear power generated another 19%, and wind and hydro about 12% each.[224]

The Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) is the leading public agency dedicated to scientific research in the country. It ranked as the 5th top governmental scientific institution worldwide (and 32nd overall) in the 2018 SCImago Institutions Rankings.[225] Spain was ranked 29th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[226]

Higher education institutions perform about a 60% of the basic research in the country.[227] Likewise, the contribution of the private sector to R&D expenditures is much lower than in other EU and OECD countries.[228]

The Spanish road system is mainly centralised, with six highways connecting Madrid to the Basque Country, Catalonia, Valencia, West Andalusia, Extremadura and Galicia. Additionally, there are highways along the Atlantic (Ferrol to Vigo), Cantabrian (Oviedo to San Sebastián) and Mediterranean (Girona to Cádiz) coasts. Spain aims to put one million electric cars on the road by 2014 as part of the government's plan to save energy and boost energy efficiency.[229] The former Minister of Industry Miguel Sebastián said that "the electric vehicle is the future and the engine of an industrial revolution."[230]

As of July 2024[update], the Spanish high-speed rail network is the longest HSR network in Europe with 3,966 km (2,464 mi)[231] and the second longest in the world, after China's. It is linking Málaga, Seville, Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and Valladolid, with the trains operated at commercial speeds up to 330 km/h (210 mph).[232] On average, the Spanish high-speed train is the fastest one in the world, followed by the Japanese bullet train and the French TGV.[233] Regarding punctuality, it is second in the world (98.5% on-time arrival) after the Japanese Shinkansen (99%).[234]

There are 47 public airports in Spain. The busiest one is the airport of Madrid (Barajas), with 60 million passengers in 2023, being the world's 15th busiest airport, as well as the European Union's third busiest. The airport of Barcelona (El Prat) is also important, with 50 million passengers in 2023, being the world's 30th-busiest airport. Other main airports are located in Majorca, Málaga, Las Palmas (Gran Canaria), and Alicante.

In 2024, Spain had a population of 48,797,875 people as recorded by Spain's Instituto Nacional de Estadística.[235] Spain's population density, at 96/km2 (249.2/sq mi), is lower than that of most Western European countries and its distribution across the country is very unequal. With the exception of the region surrounding the capital, Madrid, the most populated areas lie around the coast. The population of Spain has risen 2+1⁄2 times since 1900, when it stood at 18.6 million, principally due to the spectacular demographic boom in the 1960s and early 1970s.[236]

In 2022, the average total fertility rate (TFR) across Spain was 1.16 children born per woman,[237] one of the lowest in the world, below the replacement rate of 2.1, it remains considerably below the high of 5.11 children born per woman in 1865.[238] Spain subsequently has one of the oldest populations in the world, with the average age of 43.1 years.[239]

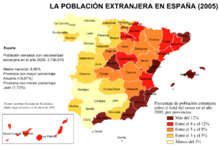

Native Spaniards make up 86.5% of the total population of Spain. After the birth rate plunged in the 1980s and Spain's population growth rate dropped, the population again trended upward initially upon the return of many Spaniards who had emigrated to other European countries during the 1970s, and more recently, fuelled by large numbers of immigrants who make up 12% of the population. The immigrants originate mainly in Latin America (39%), North Africa (16%), Eastern Europe (15%), and Sub-Saharan Africa (4%).[240]

In 2008, Spain granted citizenship to 84,170 persons, mostly to people from Ecuador, Colombia and Morocco.[241] Spain has a number of descendants of populations from former colonies, especially Latin America and North Africa. Smaller numbers of immigrants from several Sub-Saharan countries have recently been settling in Spain. There are also sizeable numbers of Asian immigrants, most of whom are of Middle Eastern, South Asian and Chinese origin. The single largest group of immigrants are European; represented by large numbers of Romanians, Britons, Germans, French and others.[242]

According to the official Spanish statistics (INE) there were 6.6 million foreign residents in Spain in 2024 (13.5%)[243] while all citizens born outside of Spain were 8.9 million in 2024, 18.31% of the total population.[244]

According to residence permit data for 2011, more than 860,000 were Romanian, about 770,000 were Moroccan, approximately 390,000 were British, and 360,000 were Ecuadorian.[245] Other sizeable foreign communities are Colombian, Bolivian, German, Italian, Bulgarian, and Chinese. There are more than 200,000 migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa living in Spain, principally Senegaleses and Nigerians.[246] Since 2000, Spain has experienced high population growth as a result of immigration flows, despite a birth rate that is only half the replacement level. This sudden and ongoing inflow of immigrants, particularly those arriving illegally by sea, has caused noticeable social tension.[247]

Within the EU, Spain had the 2nd highest immigration rate in percentage terms after Cyprus, but by a great margin, the highest in absolute numbers, up to 2008.[248] The number of immigrants in Spain had grown up from 500,000 people in 1996 to 5.2 million in 2008 out of a total population of 46 million.[249] In 2005 alone, a regularisation programme increased the legal immigrant population by 700,000 people.[250] There are a number of reasons for the high level of immigration, including Spain's cultural ties with Latin America, its geographical position, the porosity of its borders, the large size of its underground economy and the strength of the agricultural and construction sectors, which demand more low cost labour than can be offered by the national workforce.

Another statistically significant factor is the large number of residents of EU origin typically retiring to Spain's Mediterranean coast. In fact, Spain was Europe's largest absorber of migrants from 2002 to 2007, with its immigrant population more than doubling as 2.5 million people arrived.[251] In 2008, prior to the onset of the economic crisis, the Financial Times reported that Spain was the most favoured destination for Western Europeans considering a move from their own country and seeking jobs elsewhere in the EU.[252]

In 2008, the government instituted a "Plan of Voluntary Return" which encouraged unemployed immigrants from outside the EU to return to their home countries and receive several incentives, including the right to keep their unemployment benefits and transfer whatever they contributed to the Spanish Social Security.[253] The programme had little effect.[254] Although the programme failed to, the sharp and prolonged economic crisis from 2010 to 2011, resulted in tens of thousands of immigrants leaving the country due to lack of jobs. In 2011 alone, more than half a million people left Spain.[255] For the first time in decades the net migration rate was expected to be negative, and nine out of 10 emigrants were foreigners.[255]

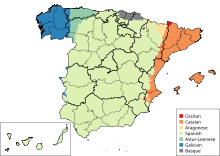

Spain is a multilingual state.[256] Spanish—featured in the 1978 Spanish Constitution as castellano ('Castilian')—has effectively been the official language of the entire country since 1931.[257] As allowed in the third article of the Constitution, the other 'Spanish languages' can also become official in their respective autonomous communities. The territoriality created by the form of co-officiality codified in the 1978 Constitution creates an asymmetry, in which Spanish speakers' rights apply to the entire territory whereas vis-à-vis the rest of co-official languages, their speakers' rights only apply in their territories.[258]

Besides Spanish, other territorialized languages include Aragonese, Aranese, Astur-Leonese, Basque, Ceutan Arabic (Darija), Catalan, Galician, Portuguese, Valencian and Tamazight, to which the Romani Caló and the sign languages may add up.[259] The number of speakers varies widely and their legal recognition is uneven, with some of the most vulnerable languages lacking any sort of effective protection.[260] Those enjoying recognition as official language in some autonomous communities include Catalan/Valencian (in Catalonia and the Balearic Islands officially named as Catalan and in the Valencian Community officially named as Valencian); Galician (in Galicia); Basque (in the Basque Country and part of Navarre); and Aranese in Catalonia.

Spanish is natively spoken by 74%, Catalan/Valencian by 17%, Galician by 7% and Basque by 2% of the Spanish population.[261]

Some of the most spoken foreign languages used by the immigrant communities include Moroccan Arabic, Romanian and English.[262]

State education in Spain is free and compulsory from the age of six to sixteen. The current education system is regulated by the 2006 educational law, LOE (Ley Orgánica de Educación), or Fundamental Law for the Education.[263] In 2014, the LOE was partially modified by the newer and controversial LOMCE law (Ley Orgánica para la Mejora de la Calidad Educativa), or Fundamental Law for the Improvement of the Education System, commonly called Ley Wert (Wert Law).[264] Since 1970 to 2014, Spain has had seven different educational laws (LGE, LOECE, LODE, LOGSE, LOPEG, LOE and LOMCE).[265]

The levels of education are preschool education, primary education,[266] secondary education[267] and post-16 education.[268] In regards to the professional development education or the vocational education, there are three levels besides the university degrees: the Formación Profesional Básica (basic vocational education); the Ciclo Formativo de Grado Medio or CFGM (medium level vocation education) which can be studied after studying the secondary education, and the Ciclo Formativo de Grado Superior or CFGS (higher level vocational education), which can be studied after studying the post-16 education level.[269]

The Programme for International Student Assessment coordinated by the OECD currently ranks the overall knowledge and skills of Spanish 15-year-olds as significantly below the OECD average of 493 in reading literacy, mathematics, and science.[270][271]

The health care system of Spain (Spanish National Health System) is considered one of the best in the world, in 7th position in the ranking elaborated by the World Health Organization.[272] The health care is public, universal and free for any legal citizen of Spain.[273] The total health spending is 9.4% of the GDP, slightly above the average of 9.3% of the OECD.

Roman Catholicism, which has a long history in Spain, remains the dominant religion. Although it no longer has official status by law, in all public schools in Spain students have to choose either a religion or ethics class. Catholicism is the religion most commonly taught, although the teaching of Islam,[275] Judaism,[276] and evangelical Christianity[277] is also recognised in law. According to a 2020 study by the Spanish Centre for Sociological Research, about 61% of Spaniards self-identify as Catholics, 3% other faiths, and about 35% identify with no religion.[278] Most Spaniards do not participate regularly in religious services.[279] Recent polls and surveys suggest that around 30% of the Spanish population is irreligious.[279][280][281]

The Spanish constitution enshrines secularism in governance, as well as freedom of religion or belief for all, saying that no religion should have a "state character", while allowing for the state to "cooperate" with religious groups.

Protestant churches have about 1,200,000 members.[282] There are about 105,000 Jehovah's Witnesses. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has approximately 46,000 adherents in 133 congregations.[283]

A study made by the Union of Islamic Communities of Spain demonstrated that there were more than 2,100,000 inhabitants of Muslim background living in Spain as of 2019[update], accounting for 4–5% of the total population of Spain. The vast majority was composed of immigrants and descendants originating from the Maghreb (especially Morocco) and other African countries. More than 879,000 (42%) of them had Spanish nationality.[284]

Judaism was practically non-existent in Spain from the 1492 expulsion until the 19th century, when Jews were again permitted to enter the country. Currently there are around 62,000 Jews in Spain, or 0.14% of the total population.

Spain is a Western country and one of the major Latin countries of Europe, and has been noted for its international cultural influence.[285] Spanish culture is marked by strong historic ties to the Catholic Church, which played a pivotal role in the country's formation and subsequent identity.[286] Spanish art, architecture, cuisine, and music have been shaped by successive waves of foreign invaders, as well as by the country's Mediterranean climate and geography. The centuries-long colonial era globalised Spanish language and culture, with Spain also absorbing the cultural and commercial products of its diverse empire.

Spain has 49 World Heritage Sites. These include the landscape of Monte Perdido in the Pyrenees, which is shared with France, the Prehistoric Rock Art Sites of the Côa Valley and Siega Verde, which is shared with Portugal, the Heritage of Mercury, shared with Slovenia and the Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests, shared with other countries of Europe.[287] In addition, Spain has also 14 Intangible cultural heritage, or "Human treasures".[288]