Протестантизм — это ветвь христианства [а] , которая подчеркивает оправдание грешников по благодати только через веру , священство всех верующих и Библию как единственный непогрешимый источник авторитета для христианской веры и практики. [ 1] [2] Пять solae суммируют основные теологические убеждения основного течения протестантизма.

Протестанты следуют теологическим принципам протестантской Реформации — движения, которое началось в XVI веке с целью реформирования Римско-католической церкви западного христианства и устранения накопившихся в ней предполагаемых ошибок, злоупотреблений и разногласий , которые возникли со времен Средневековья . [3] [b] Реформация началась в Центральной Европе , среди различных немецких государств, королевств, герцогств и княжеств 600-летней Священной Римской империи [c] 31 октября 1517 года , когда доктор Мартин Лютер (1483-1546) опубликовал свои « Девяносто пять тезисов », прибив копию к огромным деревянным дверям Замка/Церкви Всех Святых (которые традиционно долгое время служили неформальной университетской доской объявлений) в своем университете Виттенберга , в городе Виттенберг , Саксония в Империи, Большой плакат содержал вписанный список ряда его предложений и заявлений («Тезисы») для академической и теологической дискуссии, аргументации и дебатов. Он суммировал его давнюю реакцию против злоупотреблений в последние десятилетия в практике и продаже оссов и индульгенций его Римско-католической церковью, которая якобы предлагала отпущение временного наказания за грехи их покупателям. [4] Однако этот термин происходит от письма-протеста немецких лютеранских князей / курфюрстов Империи в 1529 году против указа Шпейерского сейма, осуждавшего учение Мартина Лютера как еретическое . [5]

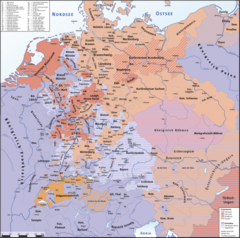

В XVI веке лютеранство распространилось из Германии [d] в скандинавский регион Северной Европы : Данию-Норвегию , Швецию , Финляндию , Ливонию и далее на северо-запад через Северный Атлантический океан к отдаленному острову Исландия [6] . Кальвинистские церкви распространились в Германии [e] , Венгрии , Нидерландах , Шотландии , Швейцарии , Франции и даже в Восточной Европе вдоль судоходных и торговых путей Балтийского моря в Польшу и прибрежные королевства Литву , Латвию и Эстонию благодаря миссионерам как евангелическо-лютеранской, так и реформатской церкви.

Новое западное христианское возрождение духа в протестантизме, выраженное в вере, учении и жизни трех наиболее важных и влиятельных теологов и священников/служителей XVI века: француза/швейцарца Жана Кальвина (1509-1564), швейцарца Гульдриха Цвингли (1484-1531) и в Шотландии Джона Нокса (1514-1572). [7] Политическое отделение Церкви Англии от Римско-католической церкви при короле Генрихе VIII (1491-1547, правил в 1509-1547), положило начало англиканству , в результате чего два его королевства на Британских островах , Королевство Англия и связанное с ним Княжество Уэльс на западе, были включены в это широкое движение Реформации под руководством реформатора и архиепископа Кентерберийского Томаса Кранмера (1489-1556, служил в 1533-1555), чья работа сформировала Церковь Англии и будущую доктрину и идентичность англиканства . [f]

Протестантизм разнообразен, будучи разделенным на различные конфессии на основе теологии и экклезиологии , не образуя единой структуры, как в случае с Католической церковью, Восточным православием или Восточным православием . [8] Протестанты придерживаются концепции невидимой церкви , в отличие от Католической, Восточной православной церкви. Менее известные Восточные православные церкви, такие как Ассирийская церковь Востока и Древняя церковь Востока , которые все понимают себя как единственную изначальную церковь — « единственную истинную церковь » — основанную Иисусом Христом (хотя некоторые протестантские конфессии, включая историческое евангелическое лютеранство, придерживаются этой позиции). [9] [10] [11] Некоторые конфессии имеют всемирный охват и распределение церковного членства , в то время как другие ограничиваются одним регионом или страной. [8] Большинство протестантов [g] являются членами нескольких протестантских конфессиональных исторических семей, таких как: адвентисты , анабаптисты , англикане/епископалы , баптисты , кальвинисты/реформаторы / конгрегационалисты / пресвитериане , [h] евангелические лютеране , методисты , моравцы , плимутские братья и общество друзей («квакеры») . [13] Неконфессиональные , харизматические , пятидесятнические /святости и межконфессиональные/ независимые церкви также находятся на подъеме, в последнее время быстро расширяясь по всему миру и составляя значительную часть протестантизма. [14] Эти различные движения, которые такие ученые, как Питер Л. Бергер , в совокупности называют «популярным протестантизмом» [i] , были названы одним из самых динамичных религиозных движений в современном мире. [15]

На сегодняшний день общее число членов организации по всему миру составляет 625 606 000 миллионов. [13] [16] [j]

Шесть принцев / курфюрстов Священной Римской империи и правители четырнадцати имперских свободных городов , которые выступили с протестом (или несогласием) против указа второго рейхстага в Шпейере 1529 года (проходившего в Шпейере в Рейнланд-Пфальце Германии ) , где термин, касающийся первых лиц, назывался уничижительно «протестантами». [18] Указ отменил уступки и принятия, сделанные евангелическим лютеранам с одобрения императора Священной Римской империи Карла V на более раннем рейхстаге в Шпейере в 1526 году , тремя годами ранее. Термин протестант , хотя изначально был чисто политическим по своей природе, позже приобрел более широкий смысл, относящийся к члену любой западной церкви, которая придерживалась основных протестантских принципов. [18] Протестант — это приверженец любой из тех христианских организаций, которые отделились от Римской церкви во время Реформации, или любой группы, произошедшей от них. [19]

Во время Реформации термин протестант практически не использовался за пределами немецкой политики. Люди, которые были вовлечены в религиозное движение, использовали слово евангелический ( ‹См. Tfd› на немецком языке : evangelisch ). Более подробную информацию см. в разделе ниже. Постепенно протестант стал общим термином, означающим любого приверженца Реформации в немецкоязычном регионе. В конечном итоге он был в некоторой степени подхвачен лютеранами, хотя сам Мартин Лютер настаивал на описательном термине « христианин» или « евангелический» как на единственно приемлемых, по его мнению, названиях для людей, исповедующих веру во Христа. Французские и швейцарские протестанты вместо этого предпочитали слово реформированный ( французский : réformé ), которое стало популярным, нейтральным и альтернативным названием для тех кальвинистов, последователей Кальвина, Цвингли и позже Джона Нокса (1514-1572) в Королевстве Шотландия на севере Британских островов .

Слово евангелический ( ‹См. Tfd› на немецком языке : evangelisch ), которое относится к евангелию , широко использовалось для тех, кто участвовал в религиозном движении в немецкоязычном регионе, начиная с 1517 года. [20] Евангелический по-прежнему является предпочтительным среди некоторых исторических протестантских конфессий в лютеранской, кальвинистской и объединенной (лютеранской и реформатской) протестантской традициях в Европе, а также тех, кто имеет тесные связи с ними. Прежде всего, этот термин используется нынешними протестантскими организациями в немецкоязычном регионе , такими как современная конфессия Протестантская церковь в Германии после Второй мировой войны и холодной войны в объединенной Федеративной Республике Германии . Немецкое слово evangelisch означает протестантский, в то время как немецкое evangelikal относится к церквям, сформированным евангелизмом . Английское слово evangelical обычно относится к евангелическим протестантским церквям, и, следовательно, к определенной части протестантизма, а не к протестантскому движению в целом. Английское слово уходит своими корнями к пилигримам - сепаратистам пуритан, двигавшимся на запад через Ла-Манш в Королевство Англия , где зародился евангелизм, а затем был перенесен через Атлантический океан пилигримами -сепаратистами 17-го века и другими иммигрантами-колонистами в Плимутскую колонию и колонию Массачусетского залива в Новой Англии из первоначальных Тринадцати колоний Британской Северной Америки (будущие Соединенные Штаты после 1776 года).

Сам Мартин Лютер всегда не любил термин «лютеранин» , предпочитая термин «евангелический », который произошел от греческого слова «euangelion », означающего «благая весть», т. е. « евангелие ». [21] Последователи Жана Кальвина , Хульдриха Цвингли и другие теологи, связанные с более радикальной реформатской традицией, также начали использовать этот термин. Чтобы различать две евангелические группы, другие начали называть их « евангелическими лютеранами» и «евангелическими реформаторами» . Это слово также относится к некоторым другим основным группам, например, евангелическим методистам . Со временем слово «евангелический» было исключено. Сами лютеране начали использовать термин «лютеранин» в середине XVI века, чтобы отличить себя от других более экстремальных групп в развивающемся протестантском движении, таких как анабаптисты и кальвинисты .

Немецкое слово reformatorisch , которое примерно переводится на английский как «реформаторский» или «реформирующий», используется в качестве альтернативы для evangelisch в немецком языке и отличается от английского reformed ( ‹See Tfd› немецкого : reformiert ), которое относится к церквям, сформированным идеями французского/швейцарского реформатора Жана Кальвина (1509-1564), швейцарского теолога Хульдриха Цвингли (1484-1531) и других реформаторских теологов той эпохи. Происходящий от слова «реформация», термин появился примерно в то же время, что и « евангелический» (1517) и « протестантский» (1529).

Различные эксперты по этому вопросу пытались определить, что делает христианскую конфессию частью протестантизма. Общее согласие, одобренное большинством из них, заключается в том, что если христианская конфессия должна считаться протестантской, она должна признать следующие три фундаментальных принципа протестантизма. [22]

Вера, подчеркнутая Лютером, в Библию как высший источник авторитета для церкви. Ранние церкви Реформации верили в критическое, но серьезное прочтение писания и считали Библию источником авторитета, более высоким, чем церковная традиция . Многочисленные злоупотребления, имевшие место в Западной церкви до протестантской Реформации, привели к тому, что реформаторы отвергли большую часть ее традиции. В начале 20-го века в Соединенных Штатах развилось менее критическое прочтение Библии, что привело к « фундаменталистскому » прочтению писания. Христианские фундаменталисты читают Библию как «безошибочное, непогрешимое » Слово Божье, как это делают католическая, восточно-православная, англиканская и лютеранская церкви, но интерпретируют ее буквалистски, не используя историко-критический метод . Методисты и англикане отличаются от лютеран и реформаторов в этом учении, поскольку они учат prima scriptura , согласно которой Писание является основным источником христианского учения, но что «традиция, опыт и разум» могут питать христианскую религию, если они находятся в гармонии с Библией ( протестантский канон ). [1] [23]

«Библейское христианство», ориентированное на глубокое изучение Библии, характерно для большинства протестантов в отличие от «церковного христианства», ориентированного на выполнение ритуалов и добрых дел, представленного католической и православной традициями. Однако квакеры , пятидесятники и духовные христиане подчеркивают Святой Дух и личную близость к Богу. [24]

Вера в то, что верующие оправданы или прощены за грехи, исключительно при условии веры во Христа , а не при сочетании веры и добрых дел . Для протестантов добрые дела являются необходимым следствием, а не причиной оправдания. [25] Однако, хотя оправдание достигается только верой, существует позиция, что вера не является nuda fides . [26] Жан Кальвин объяснял, что «поэтому только вера оправдывает, и все же вера, которая оправдывает, не одна: так же как только тепло солнца согревает землю, и все же на солнце оно не одно». [26] Лютеране и реформатские христиане отличаются от методистов в своем понимании этой доктрины. [27]

Универсальное священство верующих подразумевает право и обязанность христианских мирян не только читать Библию на родном языке , но и принимать участие в управлении и всех общественных делах Церкви. Оно противостоит иерархической системе, которая помещает суть и авторитет Церкви в исключительное священство и которая делает рукоположенных священников необходимыми посредниками между Богом и людьми. [25] Оно отличается от концепции священства всех верующих, которая не предоставляла отдельным лицам права толковать Библию отдельно от христианской общины в целом, потому что универсальное священство открывало дверь для такой возможности. [28] Есть ученые, которые ссылаются на то, что эта доктрина имеет тенденцию подводить все различия в церкви под одну духовную сущность. [29] Кальвин ссылался на универсальное священство как на выражение отношений между верующим и его Богом, включая свободу христианина приходить к Богу через Христа без человеческого посредничества. [30] Он также утверждал, что этот принцип признает Христа пророком , священником и царем и что его священство разделено с его народом. [30]

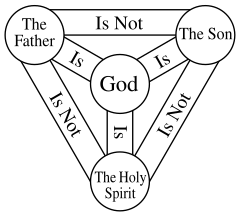

Протестанты, придерживающиеся Никейского символа веры, верят в трех лиц ( Бога Отца , Бога Сына и Бога Святого Духа ) как в единого Бога.

Движения, возникшие во времена протестантской Реформации, но не являющиеся частью протестантизма (например, унитарианство ), отвергают Троицу . Это часто служит причиной исключения унитарианского универсализма , пятидесятничества-единственника и других движений из протестантизма различными наблюдателями. Унитарианство продолжает присутствовать в основном в Трансильвании , Англии и Соединенных Штатах. [28]

Пять solae — это пять латинских фраз (или лозунгов), которые появились во время протестантской Реформации и обобщают основные различия в теологических убеждениях реформаторов в противовес учению католической церкви того времени. [1] Латинское слово sola означает «один», «единственный» или «единственный».

Использование фраз в качестве резюме учения возникло со временем во время Реформации, на основе всеобъемлющего лютеранского и реформатского принципа sola scriptura (только по Писанию). [1] Эта идея содержит четыре основных доктрины Библии: что ее учение необходимо для спасения (необходимость); что все учение, необходимое для спасения, исходит только из Библии (достаточность); что все, чему учит Библия, верно (безошибочность); и что благодаря Святому Духу, побеждающему грех, верующие могут читать и понимать истину из самой Библии, хотя понимание и затруднительно, поэтому средством, используемым для направления отдельных верующих к истинному учению, часто является взаимное обсуждение в церкви (ясность).

Необходимость и непогрешимость были устоявшимися идеями, вызывавшими мало критики, хотя позже они стали предметом дебатов извне в эпоху Просвещения . Однако самой спорной идеей в то время было представление о том, что любой может просто взять Библию и узнать достаточно, чтобы обрести спасение. Хотя реформаторы были озабочены экклезиологией (доктриной о том, как работает церковь как тело), у них было иное понимание процесса, в котором истины в Священном Писании применялись к жизни верующих, по сравнению с идеей католиков о том, что определенные люди в церкви или идеи, которые были достаточно старыми, имели особый статус в предоставлении понимания текста.

Второй главный принцип, sola fide (только верой), утверждает, что веры во Христа достаточно для вечного спасения и оправдания. Хотя он и аргументируется из Священного Писания и, следовательно, логически вытекает из sola scriptura , это руководящий принцип работы Лютера и более поздних реформаторов. Поскольку sola scriptura ставила Библию в качестве единственного источника учения, sola fide воплощает в себе основную направленность учения, к которому реформаторы хотели вернуться, а именно прямую, тесную, личную связь между Христом и верующим, отсюда утверждение реформаторов, что их работа была христоцентричной.

Другие solas как утверждения появились позже, но мысли, которые они представляют, также были частью ранней Реформации.

Протестантское движение начало разделяться на несколько отдельных ветвей в середине-конце XVI века. Одним из центральных пунктов расхождения был спор о Евхаристии . Ранние протестанты отвергли католическую догму пресуществления , которая учит, что хлеб и вино, используемые в жертвенном обряде мессы, теряют свою природную субстанцию, превращаясь в тело, кровь, душу и божественность Христа. Они не соглашались друг с другом относительно присутствия Христа, его тела и крови в Святом Причастии.

Протестанты отвергают католическую доктрину папского превосходства и имеют различные взгляды на количество таинств , реальное присутствие Христа в Евхаристии , а также вопросы церковного устройства и апостольской преемственности . [43] [44]

Многие из отдельных идей, подхваченных различными реформаторами, имели исторических предшественников; однако называть их протореформаторами спорно, поскольку часто их теология также включала компоненты, которые не связаны с более поздними протестантами, или которые утверждались некоторыми протестантами, но отрицались другими, или которые были похожи только внешне.

Одним из первых людей, которого восхваляют как предшественника протестантизма, является Иовиниан , живший в четвертом веке нашей эры. Он нападал на монашество , аскетизм и считал, что спасенный верующий никогда не может быть побежден сатаной. [45]

В IX веке теолог Готтшалк из Орбе был осужден католической церковью за ересь. Готтшалк считал, что спасение Иисуса было ограничено и что его искупление было только для избранных. [46] Теология Готтшалка предвосхитила протестантскую реформацию. [47] [48] [ самостоятельно опубликованный источник? ] Ратрамнус также защищал теологию Готтшалка и отрицал реальное присутствие Христа в Евхаристии; его труды также повлияли на более позднюю протестантскую реформацию. [49] Клавдий Туринский в IX веке также придерживался протестантских идей, таких как вера в одиночку и отрицание верховенства Петра. [50]

В конце 1130-х годов Арнольд из Брешии , итальянский каноник, стал одним из первых теологов, попытавшихся реформировать Католическую церковь. После его смерти его учение об апостольской бедности получило распространение среди арнольдистов , а позднее и более широко среди вальденсов и духовных францисканцев , хотя ни одно его письменное слово не пережило официального осуждения. В начале 1170-х годов Петр Вальдо основал вальденсов. Он отстаивал толкование Евангелия, которое привело к конфликтам с Католической церковью. К 1215 году вальденсы были объявлены еретическими и подвергались преследованиям. Несмотря на это, движение продолжает существовать и по сей день в Италии как часть более широкой реформаторской традиции .

В 1370-х годах оксфордский теолог и священник Джон Уиклиф , позже названный «Утренней звездой Реформации», начал свою деятельность в качестве английского реформатора. Он отверг папскую власть над светской властью (в том смысле, что любой человек в смертном грехе терял свою власть и ему следовало сопротивляться: священник с имуществом, такой как папа, был в таком тяжком грехе), возможно, перевел Библию на разговорный английский язык и проповедовал антиклерикальные и библейски-центрированные реформы. Его отрицание реального божественного присутствия в элементах Евхаристии предвещало подобные идеи Хульдриха Цвингли в 16 веке. Поклонники Уиклифа стали известны как « лолларды ». [51]

Начиная с первого десятилетия XV века, Ян Гус — католический священник, чешский реформатор и профессор — под влиянием трудов Джона Уиклифа основал движение гуситов . Он решительно отстаивал свою реформистскую богемскую религиозную конфессию. Он был отлучен от церкви и сожжен на костре в Констанце , епископство Констанц , в 1415 году светскими властями за нераскаянную и упорную ересь. После его казни вспыхнуло восстание. Гуситы отразили пять непрерывных крестовых походов, провозглашенных против них Папой .

Позже теологические споры привели к расколу в гуситском движении. Утраквисты утверждали, что и хлеб, и вино должны быть предложены людям во время Евхаристии. Другой крупной фракцией были табориты , которые выступили против утраквистов в битве при Липанах во время гуситских войн . Среди гуситов было две отдельные партии: умеренное и радикальное движения. Другие более мелкие региональные гуситские ветви в Богемии включали адамитов , оребитов , сирот и пражцев.

Гуситские войны завершились победой императора Священной Римской империи Сигизмунда , его католических союзников и умеренных гуситов и поражением радикальных гуситов. Напряженность возросла, когда Тридцатилетняя война достигла Богемии в 1620 году. Как умеренные, так и радикальные гуситы все больше преследовались католиками и армиями императора Священной Римской империи.

В 14 веке немецкая мистическая группа под названием Gottesfreunde критиковала католическую церковь и ее коррупцию. Многие из их лидеров были казнены за нападки на католическую церковь, и они верили, что суд Божий скоро придет на церковь. Gottesfreunde были демократическим мирянским движением и предшественниками Реформации и делали сильный акцент на святости и благочестии, [52]

Начиная с 1475 года итальянский монах-доминиканец Джироламо Савонарола призывал к христианскому обновлению. Позже сам Мартин Лютер прочитал некоторые из трудов монаха и восхвалял его как мученика и предтечу, чьи идеи о вере и благодати предвосхитили учение самого Лютера об оправдании только верой. [53]

Некоторые из последователей Гуса основали Unitas Fratrum — «Единство братьев», — которое было возобновлено под руководством графа Николауса фон Цинцендорфа в Хернхуте , Саксония , в 1722 году после его почти полного уничтожения в Тридцатилетней войне и Контрреформации («Католической Реформации») . Сегодня его обычно называют по-английски Моравской церковью , а по-немецки — Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine .

В XV веке три немецких теолога предвосхитили Реформацию: Вессель Гансфорт , Иоганн Рухат фон Везель и Иоганнес фон Гох . Они придерживались таких идей, как предопределение , sola scriptura и невидимая церковь , и отрицали римско-католический взгляд на оправдание и авторитет Папы, а также подвергали сомнению монашество . [54]

Вессель Гансфорт также отрицал пресуществление и предвосхитил лютеранскую точку зрения на оправдание только верой. [55]

Протестантская Реформация началась как попытка реформировать Католическую церковь .

31 октября 1517 года, в канун Дня всех святых , Мартин Лютер якобы прибил свои Девяносто пять тезисов , также известные как Диспут о силе индульгенций, на двери церкви Всех святых в Виттенберге , Германия, в которых подробно описывались доктринальные и практические злоупотребления Католической церкви, особенно продажа индульгенций . В тезисах обсуждались и критиковались многие аспекты Церкви и папства, включая практику чистилища , особое правосудие и авторитет папы. Позже Лютер напишет работы против католической преданности Деве Марии , заступничества и преданности святым, обязательного целибата священников, монашества, авторитета папы, церковного закона, цензуры и отлучения , роли светских правителей в религиозных вопросах, взаимоотношений между христианством и законом, добрых дел и таинств. [56]

Реформация была триумфом грамотности и нового печатного станка, изобретенного Иоганном Гутенбергом . [57] [k] Перевод Библии Лютером на немецкий язык стал решающим моментом в распространении грамотности и также стимулировал печать и распространение религиозных книг и памфлетов. Начиная с 1517 года религиозные памфлеты заполонили большую часть Европы. [59] [l]

После отлучения Лютера и осуждения Реформации Папой Римским, работа и сочинения Жана Кальвина оказали влияние на установление свободного консенсуса между различными группами в Швейцарии, Шотландии, Венгрии, Германии и других местах. После изгнания епископа в 1526 году и безуспешных попыток реформатора Берна Уильяма Фареля Кальвину было предложено использовать организационные навыки, которые он приобрел, будучи студентом юридического факультета, для наведения порядка в городе Женева . Его постановления 1541 года включали сотрудничество церковных дел с городским советом и консисторией, чтобы привнести нравственность во все сферы жизни. После основания Женевской академии в 1559 году Женева стала неофициальной столицей протестантского движения, предоставляя убежище протестантским изгнанникам со всей Европы и обучая их как кальвинистских миссионеров. Вера продолжала распространяться после смерти Кальвина в 1563 году.

Протестантизм также распространился из немецких земель во Францию, где протестанты получили прозвище гугенотов (термин несколько необъяснимого происхождения). Кальвин продолжал интересоваться французскими религиозными делами из своей базы в Женеве. Он регулярно обучал пасторов, чтобы они руководили там общинами. Несмотря на жестокие преследования, реформаторская традиция уверенно продвигалась в больших слоях страны, привлекая людей, отчужденных косностью и самодовольством католического истеблишмента. Французский протестантизм приобрел отчетливо политический характер, что стало еще более очевидным из-за обращений дворян в 1550-х годах. Это создало предпосылки для серии конфликтов, известных как Французские религиозные войны . Гражданские войны получили импульс с внезапной смертью Генриха II Французского в 1559 году. Зверства и возмущение стали определяющими характеристиками того времени, проиллюстрированными в своей наибольшей интенсивности в Варфоломеевской ночи в августе 1572 года, когда католическая партия уничтожила от 30 000 до 100 000 гугенотов по всей Франции. Войны закончились только тогда, когда Генрих IV Французский издал Нантский эдикт , обещавший официальную терпимость протестантскому меньшинству, но на весьма ограниченных условиях. Католицизм оставался официальной государственной религией , и состояние французских протестантов постепенно ухудшалось в течение следующего столетия, достигнув кульминации в Фонтенблоском эдикте Людовика XIV , который отменил Нантский эдикт и снова сделал католицизм единственной законной религией. В ответ на Фонтенблоский эдикт Фридрих Вильгельм I, курфюрст Бранденбургский, провозгласил Потсдамский эдикт , предоставляющий свободный проход беженцам-гугенотам. В конце XVII века многие гугеноты бежали в Англию, Нидерланды, Пруссию, Швейцарию, а также в английские и голландские заморские колонии. Значительная община во Франции осталась в регионе Севенны .

Параллельно с событиями в Германии в Швейцарии началось движение под руководством Хульдриха Цвингли. Цвингли был ученым и проповедником, который в 1518 году переехал в Цюрих. Хотя два движения пришли к согласию по многим вопросам теологии, некоторые неразрешенные разногласия держали их раздельно. Давняя обида между немецкими государствами и Швейцарской конфедерацией привела к жарким дебатам о том, насколько Цвингли был обязан своими идеями лютеранству. Немецкий принц Филипп Гессенский увидел потенциал в создании союза между Цвингли и Лютером. В 1529 году в его замке состоялась встреча, теперь известная как Марбургский коллоквиум , который стал печально известным из-за своей неудачи. Двое мужчин не смогли прийти к какому-либо соглашению из-за их спора по поводу одной ключевой доктрины.

В 1534 году король Генрих VIII положил конец всей папской юрисдикции в Англии после того, как Папа не смог аннулировать его брак с Екатериной Арагонской (из-за политических соображений, связанных с императором Священной Римской империи); [61] это открыло дверь реформаторским идеям. Реформаторы в Церкви Англии чередовали симпатии к древней католической традиции и более реформаторским принципам, постепенно развиваясь в традицию, считающуюся средним путем ( через медиа ) между католической и протестантской традициями. Английская Реформация следовала определенному курсу. Иной характер английской Реформации был обусловлен прежде всего тем фактом, что изначально она была обусловлена политическими потребностями Генриха VIII. Король Генрих решил отстранить Церковь Англии от власти Рима. В 1534 году Акт о супремати признал Генриха единственным верховным главой Церкви Англии на земле . Между 1535 и 1540 годами при Томасе Кромвеле была введена в действие политика, известная как Роспуск монастырей . После краткой католической реставрации во время правления Марии I, в правление Елизаветы I сложился свободный консенсус . Религиозное урегулирование Елизаветы в значительной степени сформировало англиканство в самобытную церковную традицию. Компромисс был непростым и мог колебаться между крайним кальвинизмом с одной стороны и католицизмом с другой. Он был относительно успешным до пуританской революции или английской гражданской войны в 17 веке.

Успех Контрреформации («Католической Реформации») на континенте и рост пуританской партии , преданной дальнейшему протестантскому реформированию, поляризовали Елизаветинскую эпоху . Раннее пуританское движение было движением за реформу в Церкви Англии, сторонники которого желали, чтобы Церковь Англии больше походила на протестантские церкви Европы, особенно Женевы. Позднее пуританское движение, часто называемое диссентерами и нонконформистами , в конечном итоге привело к формированию различных реформатских конфессий.

Шотландская Реформация 1560 года решительно сформировала Церковь Шотландии . [62] Реформация в Шотландии достигла своей церковной кульминации в создании церкви по реформатским линиям, а политически — в торжестве английского влияния над французским. Джон Нокс считается лидером шотландской Реформации. Шотландский парламент Реформации 1560 года аннулировал власть папы Актом о папской юрисдикции 1560 года , запретил служение мессы и одобрил протестантское исповедание веры. Это стало возможным благодаря революции против французской гегемонии при режиме регентши Марии де Гиз , которая управляла Шотландией от имени своей отсутствующей дочери .

Среди наиболее выдающихся деятелей протестантской Реформации были Якоб Арминий , Теодор Беза , Мартин Буцер , Андреас фон Карлштадт , Генрих Буллингер , Бальтазар Губмайер , Томас Кранмер , Уильям Фарель , Томас Мюнцер , Лаврентий Петри , Олаус Петри , Филипп Меланхтон , Менно Симонс , Луи де Беркен , Примож Трубар и Джон Смит .

В ходе этого религиозного потрясения, Немецкая крестьянская война 1524-25 годов охватила Баварские , Тюрингенские и Швабские княжества. После Восьмидесятилетней войны в Нидерландах и Французских религиозных войн конфессиональное разделение государств Священной Римской империи в конечном итоге вылилось в Тридцатилетнюю войну между 1618 и 1648 годами. Она опустошила большую часть Германии , убив от 25% до 40% ее населения. [63] Основными принципами Вестфальского мира , положившего конец Тридцатилетней войне, были:

Великие пробуждения были периодами быстрого и драматического религиозного возрождения в англо-американской религиозной истории.

Первое Великое Пробуждение было евангельским и возрождающим движением, которое охватило протестантскую Европу и Британскую Америку , особенно американские колонии в 1730-х и 1740-х годах, оставив неизгладимое влияние на американский протестантизм . Оно возникло в результате мощной проповеди, которая давала слушателям чувство глубокого личного откровения об их потребности в спасении Иисусом Христом. Отстраняясь от ритуала, церемонии, сакраментализма и иерархии, оно сделало христианство чрезвычайно личным для обычного человека, способствуя глубокому чувству духовной убежденности и искупления, а также поощряя самоанализ и приверженность новому стандарту личной морали. [65]

Второе великое пробуждение началось около 1790 года. Оно набрало обороты к 1800 году. После 1820 года членство быстро росло среди баптистских и методистских общин, чьи проповедники возглавляли движение. Оно прошло свой пик к концу 1840-х годов. Его описывали как реакцию на скептицизм, деизм и рационализм , хотя почему эти силы стали достаточно давящими в то время, чтобы вызвать возрождения, до конца не понятно. [66] Оно привлекло миллионы новых членов в существующие евангельские конфессии и привело к образованию новых конфессий.

Третье великое пробуждение относится к гипотетическому историческому периоду, который был отмечен религиозным активизмом в американской истории и охватывает конец 1850-х годов и начало 20-го века. [67] Оно повлияло на пиетистские протестантские конфессии и имело сильный элемент социального активизма. [68] Оно черпало силу из постмилленаристской веры в то, что Второе пришествие Христа произойдет после того, как человечество реформирует всю землю. Оно было связано с Социальным евангельским движением, которое применяло христианство к социальным вопросам и получило свою силу от Пробуждения, как и всемирное миссионерское движение. Появились новые группировки, такие как движения Святости , Назарянина и Христианской науки . [69]

Четвертое Великое Пробуждение было христианским религиозным пробуждением, которое, по словам некоторых ученых, в частности Роберта Фогеля , произошло в Соединенных Штатах в конце 1960-х и начале 1970-х годов, в то время как другие рассматривают эпоху после Второй мировой войны . Терминология является спорной. Таким образом, сама идея Четвертого Великого Пробуждения не была общепринятой. [70]

В 1814 году «Пробуждение» охватило кальвинистские регионы Швейцарии и Франции.

В 1904 году протестантское возрождение в Уэльсе оказало огромное влияние на местное население. Часть британской модернизации, оно привлекло множество людей в церкви, особенно методистские и баптистские. [71]

Примечательным событием в протестантском христианстве 20-го века стал подъем современного пятидесятнического движения . Возникнув из методистских и уэслианских корней, оно возникло из собраний в городской миссии на улице Азуза в Лос-Анджелесе. Оттуда оно распространилось по всему миру, переносимое теми, кто испытал то, что, по их мнению, было чудесными движениями Бога там. Эти проявления, подобные Пятидесятнице, постоянно были очевидны на протяжении всей истории, например, в двух Великих Пробуждениях. Пятидесятничество, которое, в свою очередь, породило харизматическое движение в уже существующих конфессиях, продолжает оставаться важной силой в западном христианстве .

В Соединенных Штатах и в других странах мира наблюдается заметный подъем евангелического крыла протестантских конфессий, особенно тех, которые являются более исключительно евангелическими, и соответствующий спад в основных либеральных церквях . В эпоху после Первой мировой войны либеральное христианство было на подъеме, и значительное количество семинарий также велось и преподавалось с либеральной точки зрения. В эпоху после Второй мировой войны тенденция начала возвращаться к консервативному лагерю в американских семинариях и церковных структурах.

В Европе наблюдался общий отход от религиозных обрядов и веры в христианские учения и переход к секуляризму . Просвещение в значительной степени ответственно за распространение секуляризма. Некоторые ученые обсуждают связь между протестантизмом и ростом секуляризма и берут в качестве аргумента широкомасштабную свободу в странах с протестантским большинством. [72] Однако один пример Франции показывает, что даже в странах с католическим большинством подавляющее влияние Просвещения принесло еще более сильный секуляризм и свободу мысли пять столетий спустя. Более надежно считать, что Реформация повлияла на критических мыслителей последующих столетий, предоставив интеллектуальную, религиозную и философскую основу, на которой будущие философы могли расширить свою критику церкви, ее теологических, философских, социальных предположений того времени. Однако следует напомнить, что первые философы Просвещения защищали христианскую концепцию мира, но она развивалась вместе с жесткой и решительной критикой Церкви, ее политики, ее этики, ее мировоззрения, ее научных и культурных предположений, что привело к девальвации всех форм институционализированного христианства, которая продолжалась на протяжении столетий. [73]

В отличие от основных лютеранских , кальвинистских и цвинглианских движений, Радикальная Реформация , которая не имела государственной поддержки, в целом отказалась от идеи «Церкви видимой» в отличие от «Церкви невидимой». Это было рациональное расширение одобренного государством протестантского инакомыслия, которое вывело ценность независимости от установленной власти на шаг дальше, утверждая то же самое для гражданской сферы. Радикальная Реформация была не мейнстримной, хотя в некоторых частях Германии, Швейцарии и Австрии большинство симпатизировало Радикальной Реформации, несмотря на интенсивные преследования, с которыми она сталкивалась как со стороны католиков, так и со стороны магистерских протестантов. [74]

Ранние анабаптисты считали, что их реформация должна очистить не только теологию, но и реальную жизнь христиан, особенно их политические и социальные отношения. [75] Поэтому церковь не должна была поддерживаться государством, ни десятиной и налогами, ни использованием меча; христианство было вопросом индивидуальных убеждений, которые не могли быть навязаны кому-либо, а скорее требовали личного решения для него. [75] Протестантские церковные лидеры, такие как Хубмайер и Хофманн, проповедовали недействительность крещения младенцев, выступая вместо этого за крещение как за последующее обращение ( «крещение верующего» ). Это не было новой доктриной для реформаторов, но ей учили более ранние группы, такие как альбигойцы в 1147 году. Хотя большинство радикальных реформаторов были анабаптистами, некоторые не отождествляли себя с основной традицией анабаптистов. Томас Мюнцер принимал участие в Немецкой крестьянской войне . Андреас Карлштадт не соглашался с теологически Хульдрихом Цвингли и Мартином Лютером, проповедуя ненасилие и отказываясь крестить младенцев, но не перекрещивая взрослых верующих. [76] Каспар Швенкфельд и Себастьян Франк находились под влиянием немецкого мистицизма и спиритуализма .

По мнению многих, связанных с радикальной Реформацией, Магистерская Реформация не зашла достаточно далеко. Радикальный реформатор Андреас фон Боденштейн Карлштадт , например, называл лютеранских теологов в Виттенберге «новыми папистами». [77] Поскольку термин «магистр» также означает «учитель», Магистерская Реформация также характеризуется акцентом на авторитете учителя. Это становится очевидным в выдающейся роли Лютера, Кальвина и Цвингли как лидеров реформаторских движений в соответствующих областях служения. Из-за своего авторитета они часто подвергались критике со стороны радикальных реформаторов за то, что они слишком похожи на римских пап. Более политическую сторону Радикальной Реформации можно увидеть в мысли и практике Ганса Гута , хотя обычно анабаптизм ассоциируется с пацифизмом.

Анабаптизм в форме его различных диверсификаций, таких как амиши , меннониты и гуттериты, вышел из радикальной реформации. Позже в истории в кругах анабаптистов возникнут братья Шварценау и апостольская христианская церковь .

Протестанты называют определенные группы конгрегаций или церквей, которые разделяют общие основополагающие доктрины и название своих групп как конфессии . [78] Термин конфессия (национальная организация) следует отличать от ветви (конфессиональная семья; традиция), общины (международная организация) и конгрегации (церкви). Пример (это не универсальный способ классификации протестантских церквей, поскольку они иногда могут сильно различаться по своей структуре), чтобы показать разницу:

Протестанты отвергают доктрину Католической церкви о том, что она является единственной истинной церковью , с некоторым учением о вере в невидимую церковь , которая состоит из всех, кто исповедует веру в Иисуса Христа. [79] Лютеранская церковь традиционно рассматривает себя как «главный ствол исторического христианского древа», основанного Христом и апостолами, утверждая, что во время Реформации Римская церковь отпала. [10] [11] Отдельные конфессии также сформировались на основе очень тонких теологических различий. Другие конфессии являются просто региональными или этническими выражениями тех же верований. Поскольку пять solas являются основными принципами протестантской веры, неконфессиональные группы и организации также считаются протестантскими.

Различные экуменические движения пытались сотрудничать или реорганизовать различные разделенные протестантские конфессии в соответствии с различными моделями союза, но разделения продолжают опережать союзы, поскольку нет всеобъемлющего органа, которому любая из церквей обязана быть верной, который мог бы авторитетно определять веру. Большинство конфессий разделяют общие убеждения в основных аспектах христианской веры, в то же время различаясь во многих второстепенных доктринах, хотя то, что является главным, а что второстепенным, является вопросом идиосинкразической веры.

Несколько стран создали свои национальные церкви , связав церковную структуру с государством. Юрисдикции, где протестантская конфессия была установлена в качестве государственной религии, включают несколько стран Северной Европы ; Дания (включая Гренландию), [80] Фарерские острова ( ее церковь является независимой с 2007 года), [81] Исландия [82] и Норвегия [83] [84] [85] создали евангелическо-лютеранские церкви. Тувалу имеет единственную установленную церковь в реформатской традиции в мире, в то время как Тонга — в методистской традиции . [86]

Церковь Англии — официально учрежденная религиозная организация в Англии, [87] [88] [89] , а также Мать-Церковь всемирного Англиканского Сообщества .

В 1869 году Финляндия стала первой страной Северной Европы, которая отменила свое евангелическо-лютеранское общество, приняв Закон о церкви. [m] Хотя церковь по-прежнему поддерживает особые отношения с государством, она не описана как государственная религия в Конституции Финляндии или других законах, принятых парламентом Финляндии . [90] В 2000 году Швеция стала второй страной Северной Европы, которая сделала это. [91]

Объединенные и объединяющие церкви — это церкви, образованные в результате слияния или иной формы объединения двух или более различных протестантских конфессий.

Исторически союзы протестантских церквей навязывались государством, как правило, для того, чтобы иметь более строгий контроль над религиозной сферой своего народа, но также и по другим организационным причинам. По мере развития современного христианского экуменизма союзы между различными протестантскими традициями становятся все более распространенными, что приводит к росту числа объединенных и объединяющихся церквей. Некоторые из недавних крупных примеров — Церковь Северной Индии (1970), Объединенная протестантская церковь Франции (2013) и Протестантская церковь в Нидерландах (2004). Поскольку основной протестантизм сокращается в Европе и Северной Америке из-за роста секуляризма или в регионах, где христианство является религией меньшинства, как на Индийском субконтиненте , реформатские , англиканские и лютеранские конфессии объединяются, часто создавая крупные общенациональные конфессии. Это явление гораздо менее распространено среди евангелических , неконфессиональных и харизматических церквей, поскольку возникают новые, и многие из них остаются независимыми друг от друга. [ необходима цитата ]

Возможно, старейшая официальная объединённая церковь находится в Германии , где Протестантская церковь в Германии является федерацией лютеранской , объединённой ( Прусский союз ) и реформатской церквей , союз, восходящий к 1817 году. Первый из серии союзов состоялся на синоде в Идштайне для образования Протестантской церкви в Гессене и Нассау в августе 1817 года, что увековечено в названии церкви Идштайна Unionskirche сто лет спустя. [92]

Во всем мире каждая объединенная или объединяющая церковь включает в себя различную смесь предшествующих протестантских конфессий. Однако тенденции видны, поскольку большинство объединенных и объединяющих церквей имеют одного или нескольких предшественников с наследием в реформатской традиции , и многие являются членами Всемирного альянса реформатских церквей .

Протестантов можно дифференцировать в зависимости от того, как на них повлияли важные движения со времен Реформации, которые сегодня рассматриваются как ответвления. Некоторые из этих движений имеют общую родословную, иногда напрямую порождая отдельные конфессии. Из-за ранее заявленного множества конфессий в этом разделе обсуждаются только самые крупные конфессиональные семьи или ответвления, которые широко считаются частью протестантизма. Это, в алфавитном порядке: адвентисты , англикане , баптисты , кальвинисты (реформаты) , гуситы , лютеране , методисты , пятидесятники , плимутские братья и квакеры . Также обсуждается небольшая, но исторически значимая ветвь анабаптистов .

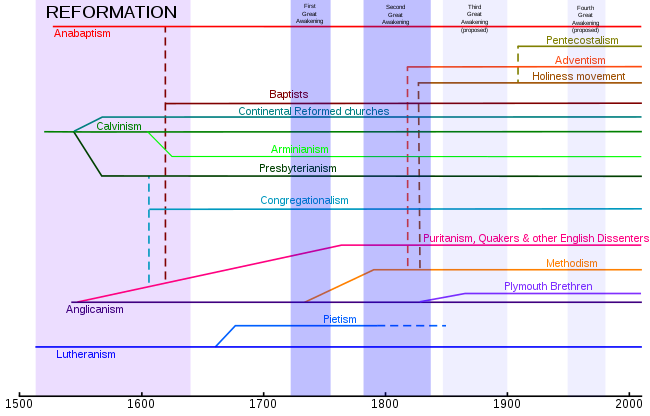

На диаграмме ниже показаны взаимоотношения и историческое происхождение основных протестантских конфессиональных семей или их частей. Из-за таких факторов, как Контрреформация («Католическая Реформация») и правового принципа Cuius regio, eius religio , многие люди жили как никодимиты , где их исповедуемая религиозная принадлежность более или менее расходилась с движением, которому они симпатизировали. В результате границы между конфессиями не разделяются так четко, как показывает эта диаграмма. Когда население подавлялось или преследовалось, чтобы симулировать приверженность доминирующей вере, на протяжении поколений оно продолжало влиять на церковь, которой оно внешне придерживалось.

Поскольку кальвинизм не был конкретно признан в Священной Римской империи до Вестфальского мира 1648 года, многие кальвинисты жили как криптокальвинисты . Из-за подавлений, связанных с Контрреформацией («Католической Реформацией») в католических странах в 16-19 веках, многие протестанты жили как криптопротестанты . Между тем, в протестантских районах католики иногда жили как криптопаписты , хотя в континентальной Европе эмиграция была более осуществима, поэтому это было менее распространено.

Адвентизм зародился в 19 веке в контексте Второго великого пробуждения в Соединенных Штатах . Название относится к вере в неизбежное Второе пришествие (или «Второе пришествие») Иисуса Христа . Уильям Миллер основал адвентистское движение в 1830-х годах. Его последователи стали известны как миллериты . [93]

Хотя адвентистские церкви имеют много общего, их теологии различаются по вопросам, является ли промежуточное состояние бессознательным сном или сознанием, является ли окончательное наказание нечестивых уничтожением или вечными муками, какова природа бессмертия, воскреснут ли нечестивые после тысячелетнего царства, и относится ли святилище Даниила 8 [94] к тому, что на небесах , или к тому, что на земле. [95] Движение поощряло изучение всей Библии , побуждая адвентистов седьмого дня и некоторые более мелкие адвентистские группы соблюдать субботу . Генеральная конференция адвентистов седьмого дня собрала основные убеждения этой церкви в 28 основных убеждениях (1980 и 2005), которые используют библейские ссылки в качестве обоснования.

В 2010 году адвентизм насчитывал около 22 миллионов верующих, разбросанных по разным независимым церквям. [96] Самая большая церковь в движении — Церковь адвентистов седьмого дня — насчитывает более 18 миллионов членов.

Анабаптизм ведёт своё начало от радикальной Реформации . Анабаптисты верят в отсрочку крещения до тех пор, пока кандидат не исповедует свою веру. Хотя некоторые считают это движение ответвлением протестантизма, другие видят в нём отдельное течение. [97] [98] Амиши , хуттериты и меннониты являются прямыми потомками движения. Братья Шварценау , Брудерхоф и Апостольская христианская церковь считаются более поздними разработками среди анабаптистов.

Название «анабаптисты », означающее «тот, кто крестит снова», было дано им их преследователями в связи с практикой повторного крещения новообращенных, которые уже были крещены в младенчестве. [99] Анабаптисты требовали, чтобы кандидаты на крещение могли сделать собственное исповедание веры, и поэтому отвергали крещение младенцев . Ранние члены этого движения не принимали название «анабаптисты» , утверждая, что, поскольку крещение младенцев было небиблейским и недействительным, крещение верующих было не повторным крещением, а фактически их первым настоящим крещением. В результате их взглядов на природу крещения и других вопросов, анабаптисты подвергались жестоким преследованиям в течение 16-го века и в 17-м веке как со стороны магистерских протестантов , так и со стороны католиков. В то время как большинство анабаптистов придерживались буквального толкования Нагорной проповеди , что исключало принятие клятв, участие в военных действиях и участие в гражданском управлении, некоторые из тех, кто практиковал повторное крещение, считали иначе. [n] Таким образом, технически они были анабаптистами, хотя консервативные амиши , меннониты и гуттериты и некоторые историки склонны считать их выходцами из истинного анабаптизма. Анабаптистские реформаторы Радикальной Реформации делятся на Радикальных и так называемый Второй фронт. Некоторые важные теологи Радикальной Реформации были Иоанн Лейденский , Томас Мюнцер , Каспар Швенкфельд , Себастьян Франк , Менно Симонс . Реформаторы Второго фронта включали Ганса Денка , Конрада Гребеля , Бальтазар Хубмайера и Феликса Манца . Многие анабаптисты сегодня все еще используют Ausbund , который является старейшим сборником гимнов, все еще находящимся в постоянном использовании.

Англиканство состоит из Церкви Англии и церквей, которые исторически связаны с ней или придерживаются схожих убеждений, практик поклонения и церковных структур. [100] Слово англиканец происходит от ecclesia anglicana , средневековой латинской фразы, датируемой по крайней мере 1246 годом, которая означает Английскую церковь . Не существует единой «англиканской церкви» с универсальной юридической властью, поскольку каждая национальная или региональная церковь имеет полную автономию . Как следует из названия, сообщество представляет собой ассоциацию церквей, находящихся в полном общении с архиепископом Кентерберийским . Подавляющее большинство англиканцев являются членами церквей, которые являются частью международного Англиканского сообщества , [101] которое насчитывает 85 миллионов приверженцев. [102]

Церковь Англии провозгласила свою независимость от Католической церкви во время Елизаветинского религиозного урегулирования . [103] Многие из новых англиканских формулировок середины XVI века тесно соответствовали формулировкам современной реформатской традиции. Эти реформы были поняты одним из тех, кто был наиболее ответственен за них, тогдашним архиепископом Кентерберийским Томасом Кранмером , как навигация по срединному пути между двумя формирующимися протестантскими традициями, а именно лютеранством и кальвинизмом. [104] К концу века сохранение в англиканстве многих традиционных литургических форм и епископата уже считалось неприемлемым теми, кто продвигал наиболее развитые протестантские принципы.

Уникальной для англиканства является Книга общей молитвы , собрание служб, которые верующие в большинстве англиканских церквей использовали на протяжении столетий. Хотя с тех пор она претерпела множество изменений, а англиканские церкви в разных странах разработали другие книги служб, Книга общей молитвы по-прежнему признается одной из связей, которые связывают англиканское сообщество вместе.

Баптисты придерживаются доктрины, что крещение должно совершаться только для исповедующих верующих ( крещение верующих , в отличие от крещения младенцев ), и что оно должно совершаться полным погружением (в отличие от обливания или окропления ). Другие принципы баптистских церквей включают в себя компетентность души (свободу), спасение только через веру , только Писание как правило веры и практики и автономию местной общины . Баптисты признают два министерских служения, пасторов и дьяконов . Баптистские церкви широко считаются протестантскими церквями, хотя некоторые баптисты отрицают эту идентичность. [105]

Разные с самого начала, те, кто сегодня идентифицируют себя как баптисты, существенно отличаются друг от друга по своим убеждениям, способам поклонения, отношению к другим христианам и пониманию того, что важно в христианском ученичестве. [106]

Историки отслеживают самую раннюю церковь, названную баптистской, в 1609 году в Амстердаме , с английским сепаратистом Джоном Смитом в качестве пастора. [107] В соответствии со своим прочтением Нового Завета , он отверг крещение младенцев и установил крещение только верующих взрослых. [108] Баптистская практика распространилась на Англию, где общие баптисты считали, что искупление Христа распространяется на всех людей, в то время как частные баптисты полагали, что оно распространяется только на избранных . В 1638 году Роджер Уильямс основал первую баптистскую общину в североамериканских колониях . В середине 18 века Первое Великое Пробуждение увеличило рост баптистов как в Новой Англии, так и на Юге. [109] Второе Великое Пробуждение на Юге в начале 19 века увеличило количество членов церкви, как и ослабление поддержки проповедниками отмены и освобождения от рабства , что было частью учений 18 века. Баптистские миссионеры распространили свою церковь на все континенты. [108]

Всемирный баптистский альянс сообщает о более чем 41 миллионе членов в более чем 150 000 общинах. [110] В 2002 году во всем мире насчитывалось более 100 миллионов баптистов и членов баптистских групп, а в Северной Америке — более 33 миллионов. [108] Крупнейшей баптистской ассоциацией является Южная баптистская конвенция , общее число членов ассоциированных церквей которой составляет более 14 миллионов. [111]

Кальвинизм , также называемый реформатской традицией, развивался несколькими теологами, такими как Мартин Буцер , Генрих Буллингер , Питер Мартир Вермильи и Хульдрих Цвингли, но эта ветвь христианства носит имя французского реформатора Жана Кальвина из-за его выдающегося влияния на нее и из-за его роли в конфессиональных и церковных дебатах на протяжении XVI века.

Этот термин в настоящее время также относится к доктринам и практикам реформатских церквей , ранним лидером которых был Кальвин. Реже он может относиться к индивидуальному учению самого Кальвина. Подробности кальвинистского богословия могут быть изложены несколькими способами. Возможно, наиболее известное резюме содержится в пяти пунктах кальвинизма , хотя эти пункты скорее определяют кальвинистский взгляд на сотериологию , чем суммируют систему в целом. В широком смысле кальвинизм подчеркивает суверенитет или правление Бога во всем — в спасении, но также и во всей жизни. Эта концепция ясно прослеживается в доктринах предопределения и полной греховности .

Крупнейшей реформатской ассоциацией является Всемирное сообщество реформатских церквей , насчитывающее более 80 миллионов членов в 211 конфессиях по всему миру. [113] [114] Существуют и более консервативные реформатские федерации, такие как Всемирное реформатское братство и Международная конференция реформатских церквей , а также независимые церкви .

Hussitism follows the teachings of Czech reformer Jan Hus, who became the best-known representative of the Bohemian Reformation and one of the forerunners of the Protestant Reformation. An early hymnal was the hand-written Jistebnice hymn book. This predominantly religious movement was propelled by social issues and strengthened Czech national awareness. Among present-day Christians, Hussite traditions are represented in the Moravian Church, Unity of the Brethren and the Czechoslovak Hussite Church.[115]

Lutheranism identifies with the theology of Martin Luther, a German monk and priest, ecclesiastical reformer, and theologian.

Lutheranism advocates a doctrine of justification "by grace alone through faith alone on the basis of Scripture alone", the doctrine that scripture is the final authority on all matters of faith, rejecting the assertion made by Catholic leaders at the Council of Trent that authority comes from both Scriptures and Tradition.[116] In addition, Lutherans accept the teachings of the first four ecumenical councils of the undivided Christian Church.[117][118]

Unlike the Reformed tradition, Lutherans retain many of the liturgical practices and sacramental teachings of the pre-Reformation Church with an emphasis on the Eucharist, or Lord's Supper. Lutheran theology differs from Reformed theology in Christology, the purpose of God's Law, divine grace, the concept of perseverance of the saints, and predestination.

Today, Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism. With approximately 80 million adherents,[119] it constitutes the third most common Protestant confession after historically Pentecostal denominations and Anglicanism.[13] The Lutheran World Federation, the largest global communion of Lutheran churches represents over 72 million people.[120] Both of these figures miscount Lutherans worldwide as many members of more generically Protestant LWF member church bodies do not self-identify as Lutheran or attend congregations that self-identify as Lutheran.[121] Additionally, there are other international organizations such as the Global Confessional and Missional Lutheran Forum, International Lutheran Council and the Confessional Evangelical Lutheran Conference, as well as Lutheran denominations that are not necessarily a member of an international organization.

Methodism identifies principally with the theology of John Wesley—an Anglican priest and evangelist. This evangelical movement originated as a revival within the 18th-century Church of England and became a separate Church following Wesley's death. Because of vigorous missionary activity, the movement spread throughout the British Empire, the United States, and beyond, today claiming approximately 80 million adherents worldwide.[122] Originally it appealed especially to laborers and slaves.

Soteriologically, most Methodists are Arminian, emphasizing that Christ accomplished salvation for every human being, and that humans must exercise an act of the will to receive it (as opposed to the traditional Calvinist doctrine of monergism). Methodism is traditionally low church in liturgy, although this varies greatly between individual congregations; the Wesleys themselves greatly valued the Anglican liturgy and tradition. Methodism is known for its rich musical tradition; John Wesley's brother, Charles, was instrumental in writing much of the hymnody of the Methodist Church,[123] and many other eminent hymn writers come from the Methodist tradition.

The Holiness movement refers to a set of practices surrounding the doctrine of Christian perfection that emerged within 19th-century Methodism, along with a number of evangelical denominations and parachurch organizations (such as camp meetings).[124] There are an estimated 12 million adherents in denominations aligned with the Wesleyan-holiness movement.[125] The Free Methodist Church, the Salvation Army and the Wesleyan Methodist Church are notable examples, while other adherents of the Holiness Movement remained within mainline Methodism, e.g. the United Methodist Church.[124]

Pentecostalism is a movement that places special emphasis on a direct personal experience of God through the baptism with the Holy Spirit. The term Pentecostal is derived from Pentecost, the Greek name for the Jewish Feast of Weeks. For Christians, this event commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the followers of Jesus Christ, as described in the second chapter of the Book of Acts.

This branch of Protestantism is distinguished by belief in the baptism with the Holy Spirit as an experience separate from conversion that enables a Christian to live a life empowered by and filled with the Holy Spirit. This empowerment includes the use of spiritual gifts such as speaking in tongues and divine healing—two other defining characteristics of Pentecostalism. Because of their commitment to biblical authority, spiritual gifts, and the miraculous, Pentecostals tend to see their movement as reflecting the same kind of spiritual power and teachings that were found in the Apostolic Age of the early church. For this reason, some Pentecostals also use the term Apostolic or Full Gospel to describe their movement.

Pentecostalism eventually spawned hundreds of new denominations, including large groups such as the Assemblies of God and the Church of God in Christ, both in the United States and elsewhere. There are over 279 million Pentecostals worldwide, and the movement is growing in many parts of the world, especially the global South. Since the 1960s, Pentecostalism has increasingly gained acceptance from other Christian traditions, and Pentecostal beliefs concerning Spirit baptism and spiritual gifts have been embraced by non-Pentecostal Christians in Protestant and Catholic churches through the Charismatic Movement. Together, Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity numbers over 500 million adherents.[126]

The Plymouth Brethren are a conservative, low church, evangelical denomination, whose history can be traced to Dublin, Ireland, in the late 1820s, originating from Anglicanism.[127][128] Among other beliefs, the group emphasizes sola scriptura. Brethren generally see themselves not as a denomination, but as a network, or even as a collection of overlapping networks, of like-minded independent churches. Although the group refused for many years to take any denominational name to itself—a stance that some of them still maintain—the title The Brethren, is one that many of their number are comfortable with in that the Bible designates all believers as brethren.

Quakers, or Friends, are members of a family of religious movements collectively known as the Religious Society of Friends. The central unifying doctrine of these movements is the priesthood of all believers.[129][130] Many Friends view themselves as members of a Christian denomination. They include those with evangelical, holiness, liberal, and traditional conservative Quaker understandings of Christianity. Unlike many other groups that emerged within Christianity, the Religious Society of Friends has actively tried to avoid creeds and hierarchical structures.[131]

There are many other Protestant denominations that do not fit neatly into the mentioned branches, and are far smaller in membership. Some groups of individuals who hold basic Protestant tenets identify themselves simply as "Christians" or "born-again Christians". They typically distance themselves from the confessionalism or creedalism of other Christian communities[132] by calling themselves "non-denominational" or "evangelical". Often founded by individual pastors, they have little affiliation with historic denominations.[133]

Although Unitarianism developed from the Protestant Reformation,[134] it is excluded from Protestantism due to its Nontrinitarian theological nature.[28][135] Unitarianism has been popular in the region of Transylvania within today's Romania, England, and the United States.[28] It originated almost simultaneously in Transylvania and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Spiritual Christianity is the group of Russian movements (Doukhobors and others), so-called folk Protestants. Their origins are varied: some were influenced by western Protestants, others from disgust of the behavior of official Orthodox priests.[136][137]

Messianic Judaism is a movement of the Jews and non-Jews, which arose in the 1960s within Evangelical Protestantism and absorbed elements of the messianic traditions in Judaism.[138]

There are also Christian movements which cross denominational lines and even branches, and cannot be classified on the same level previously mentioned forms. Evangelicalism is a prominent example. Some of those movements are active exclusively within Protestantism, some are Christian-wide. Transdenominational movements are sometimes capable of affecting parts of the Catholic Church, such as does it the Charismatic Movement, which aims to incorporate beliefs and practices similar to Pentecostals into the various branches of Christianity. Neo-charismatic churches are sometimes regarded as a subgroup of the Charismatic Movement. Both are put under a common label of Charismatic Christianity (so-called Renewalists), along with Pentecostals. Nondenominational churches and various house churches often adopt, or are akin to one of these movements.

Megachurches are usually influenced by interdenominational movements. Globally, these large congregations are a significant development in Protestant Christianity. In the United States, the phenomenon has more than quadrupled in the past two decades.[139] It has since spread worldwide.

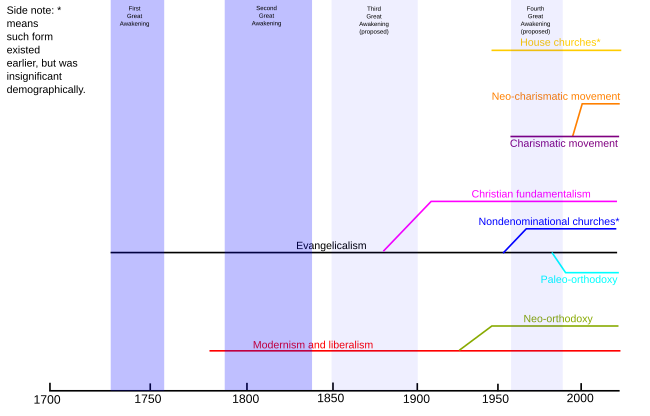

The chart below shows the mutual relations and historical origins of the main interdenominational movements and other developments within Protestantism.

Evangelicalism, or evangelical Protestantism,[o] is a worldwide, transdenominational movement which maintains that the essence of the gospel consists in the doctrine of salvation by grace through faith in Jesus Christ's atonement.[140][141]

Evangelicals are Christians who believe in the centrality of the conversion or "born again" experience in receiving salvation, believe in the authority of the Bible as God's revelation to humanity and have a strong commitment to evangelism or sharing the Christian message.

It gained great momentum in the 18th and 19th centuries with the emergence of Methodism and the Great Awakenings in Britain and North America. The origins of Evangelicalism are usually traced back to the English Methodist movement, Nicolaus Zinzendorf, the Moravian Church, Lutheran pietism, Presbyterianism and Puritanism.[96] Among leaders and major figures of the Evangelical Protestant movement were John Wesley, George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards, Billy Graham, Harold John Ockenga, John Stott and Martyn Lloyd-Jones.

There are an estimated 285,480,000 Evangelicals, corresponding to 13% of the Christian population and 4% of the total world population. The Americas, Africa and Asia are home to the majority of Evangelicals. The United States has the largest concentration of Evangelicals.[142] Evangelicalism is gaining popularity both in and outside the English-speaking world, especially in Latin America and the developing world.

The Charismatic movement is the international trend of historically mainstream congregations adopting beliefs and practices similar to Pentecostals. Fundamental to the movement is the use of spiritual gifts. Among Protestants, the movement began around 1960.

In the United States, Episcopalian Dennis Bennett is sometimes cited as one of the charismatic movement's seminal influence.[143] In the United Kingdom, Colin Urquhart, Michael Harper, David Watson and others were in the vanguard of similar developments. The Massey conference in New Zealand, 1964 was attended by several Anglicans, including the Rev. Ray Muller, who went on to invite Bennett to New Zealand in 1966, and played a leading role in developing and promoting the Life in the Spirit seminars. Other Charismatic movement leaders in New Zealand include Bill Subritzky.

Larry Christenson, a Lutheran theologian based in San Pedro, California, did much in the 1960s and 1970s to interpret the charismatic movement for Lutherans. A very large annual conference regarding that matter was held in Minneapolis. Charismatic Lutheran congregations in Minnesota became especially large and influential; especially "Hosanna!" in Lakeville, and North Heights in St. Paul. The next generation of Lutheran charismatics cluster around the Alliance of Renewal Churches. There is considerable charismatic activity among young Lutheran leaders in California centered around an annual gathering at Robinwood Church in Huntington Beach. Richard A. Jensen's Touched by the Spirit published in 1974, played a major role of the Lutheran understanding to the charismatic movement.

In Congregational and Presbyterian churches which profess a traditionally Calvinist or Reformed theology there are differing views regarding present-day continuation or cessation of the gifts (charismata) of the Spirit.[144][145] Generally, however, Reformed charismatics distance themselves from renewal movements with tendencies which could be perceived as overemotional, such as Word of Faith, Toronto Blessing, Brownsville Revival and Lakeland Revival. Prominent Reformed charismatic denominations are the Sovereign Grace Churches and the Every Nation Churches in the US, in Great Britain there is the Newfrontiers churches and movement, which leading figure is Terry Virgo.[146]

A minority of Seventh-day Adventists today are charismatic. They are strongly associated with those holding more "progressive" Adventist beliefs. In the early decades of the church charismatic or ecstatic phenomena were commonplace.[147][148]

Neo-charismatic churches are a category of churches in the Christian Renewal movement. Neo-charismatics include the Third Wave, but are broader. Now more numerous than Pentecostals (first wave) and charismatics (second wave) combined, owing to the remarkable growth of postdenominational and independent charismatic groups.[149]

Neo-charismatics believe in and stress the post-Biblical availability of gifts of the Holy Spirit, including glossolalia, healing, and prophecy. They practice laying on of hands and seek the "infilling" of the Holy Spirit. However, a specific experience of baptism with the Holy Spirit may not be requisite for experiencing such gifts. No single form, governmental structure, or style of church service characterizes all neo-charismatic services and churches.

Some nineteen thousand denominations, with approximately 295 million individual adherents, are identified as neo-charismatic.[150]

Arminianism is based on theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants. His teachings held to the five solae of the Reformation, but they were distinct from particular teachings of Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin, and other Protestant Reformers. Jacobus Arminius was a student of Theodore Beza at the Theological University of Geneva. Arminianism is known to some as a soteriological diversification of Calvinism.[151] However, to others, Arminianism is a reclamation of early Church theological consensus.[152] Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the Remonstrance (1610), a theological statement signed by 45 ministers and submitted to the States General of the Netherlands. Many Christian denominations have been influenced by Arminian views on the will of man being freed by grace prior to regeneration, notably the Baptists in the 16th century,[153] the Methodists in the 18th century and the Seventh-day Adventist Church in the 19th century.

The original beliefs of Jacobus Arminius himself are commonly defined as Arminianism, but more broadly, the term may embrace the teachings of Hugo Grotius, John Wesley, and others as well. Classical Arminianism and Wesleyan Arminianism are the two main schools of thought. Wesleyan Arminianism is often identical with Methodism. The two systems of Calvinism and Arminianism share both history and many doctrines, and the history of Christian theology. However, because of their differences over the doctrines of divine predestination and election, many people view these schools of thought as opposed to each other. In short, the difference can be seen ultimately by whether God allows His desire to save all to be resisted by an individual's will (in the Arminian doctrine) or if God's grace is irresistible and limited to only some (in Calvinism). Some Calvinists assert that the Arminian perspective presents a synergistic system of Salvation and therefore is not only by grace, while Arminians firmly reject this conclusion. Many consider the theological differences to be crucial differences in doctrine, while others find them to be relatively minor.[154]

Pietism was an influential movement within Lutheranism that combined the 17th-century Lutheran principles with the Reformed emphasis on individual piety and living a vigorous Christian life.[155]

It began in the late 17th century, reached its zenith in the mid-18th century, and declined through the 19th century, and had almost vanished in America by the end of the 20th century. While declining as an identifiable Lutheran group, some of its theological tenets influenced Protestantism generally, inspiring the Anglican priest John Wesley to begin the Methodist movement and Alexander Mack to begin the Brethren movement under an influence of Anabaptists.[156]

Though Pietism shares an emphasis on personal behavior with the Puritan movement, and the two are often confused, there are important differences, particularly in the concept of the role of religion in government.[157]

The Puritans were a group of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries, which sought to purify the Church of England of what they considered to be Catholic practices, maintaining that the church was only partially reformed. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some of the returning clergy exiled under Mary I shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England.

Puritans were blocked from changing the established church from within, and were severely restricted in England by laws controlling the practice of religion. Their beliefs, however, were transported by the emigration of congregations to the Netherlands (and later to New England), and by evangelical clergy to Ireland (and later into Wales), and were spread into lay society and parts of the educational system, particularly certain colleges of the University of Cambridge. The first Protestant sermon delivered in England was in Cambridge, with the pulpit that this sermon was delivered from surviving to today.[158][159] They took on distinctive beliefs about clerical dress and in opposition to the episcopal system, particularly after the 1619 conclusions of the Synod of Dort they were resisted by the English bishops. They largely adopted Sabbatarianism in the 17th century, and were influenced by millennialism.

They formed, and identified with various religious groups advocating greater purity of worship and doctrine, as well as personal and group piety. Puritans adopted a Reformed theology, but they also took note of radical criticisms of Zwingli in Zurich and Calvin in Geneva. In church polity, some advocated for separation from all other Christians, in favor of autonomous gathered churches. These separatist and independent strands of Puritanism became prominent in the 1640s. Although the English Civil War (which expanded into the Wars of the Three Kingdoms) began over a contest for political power between the King of England and the House of Commons, it divided the country along religious lines as episcopalians within the Church of England sided with the Crown and Presbyterians and Independents supported Parliament (after the defeat of the Royalists, the House of Lords as well as the Monarch were removed from the political structure of the state to create the Commonwealth). The supporters of a Presbyterian polity in the Westminster Assembly were unable to forge a new English national church, and the Parliamentary New Model Army, which was made up primarily of Independents, under Oliver Cromwell first purged Parliament, then abolished it and established The Protectorate.

England's trans-Atlantic colonies in the war followed varying paths depending on their internal demographics. In the older colonies, which included Virginia (1607) and its offshoot Bermuda (1612), as well as Barbados and Antigua in the West Indies (collectively the targets in 1650 of An Act for prohibiting Trade with the Barbadoes, Virginia, Bermuda and Antego), Episcopalians remained the dominant church faction and the colonies remained Royalist 'til conquered or compelled to accept the new political order. In Bermuda, with control of the local government and the army (nine infantry companies of Militia plus coastal artillery), the Royalists forced Parliament-backing religious Independents into exile to settle the Bahamas as the Eleutheran Adventurers.[160][161][162]

Episcopalian was re-established following the Restoration. A century later, non-conforming Protestants, along with the Protestant refugees from continental Europe, were to be among the primary instigators of the war of secession that led to the founding of the United States of America.

A non-fundamentalist rejection of liberal Christianity along the lines of the Christian existentialism of Søren Kierkegaard, who attacked the Hegelian state churches of his day for "dead orthodoxy", neo-orthodoxy is associated primarily with Karl Barth, Jürgen Moltmann, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Neo-orthodoxy sought to counter-act the tendency of liberal theology to make theological accommodations to modern scientific perspectives. Sometimes called "crisis theology", in the existentialist sense of the word crisis, also sometimes called neo-evangelicalism, which uses the sense of "evangelical" pertaining to continental European Protestants rather than American evangelicalism. "Evangelical" was the originally preferred label used by Lutherans and Calvinists, but it was replaced by the names some Catholics used to label a heresy with the name of its founder.

Paleo-orthodoxy is a movement similar in some respects to neo-evangelicalism but emphasizing the ancient Christian consensus of the undivided church of the first millennium AD, including in particular the early creeds and church councils as a means of properly understanding the scriptures. This movement is cross-denominational. A prominent theologian in this group is Thomas Oden, a Methodist.

In reaction to liberal Bible critique, fundamentalism arose in the 20th century, primarily in the United States, among those denominations most affected by Evangelicalism. Fundamentalist theology tends to stress Biblical inerrancy and Biblical literalism.[166]

Toward the end of the 20th century, some have tended to confuse evangelicalism and fundamentalism; however, the labels represent very distinct differences of approach that both groups are diligent to maintain, although because of fundamentalism's dramatically smaller size it often gets classified simply as an ultra-conservative branch of evangelicalism.

Modernism and liberalism do not constitute rigorous and well-defined schools of theology, but are rather an inclination by some writers and teachers to integrate Christian thought into the spirit of the Age of Enlightenment. New understandings of history and the natural sciences of the day led directly to new approaches to theology. Its opposition to the fundamentalist teaching resulted in religious debates, such as the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy within the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America in the 1920s.